By Martin Tompa

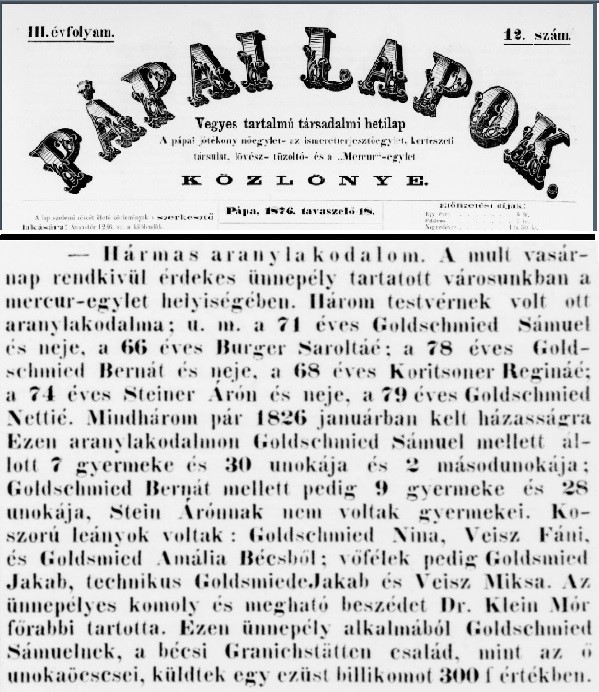

While researching my Goldschmid family from Pápa, Hungary, I found on the Hungaricana website a wonderful, short newspaper article in the March 18, 1876, issue of the Pápa newspaper Pápai Lapok.

The article was about my great-great-great-grandparents Sámuel Goldschmid and Sarolta Burger on the occasion of their 50th wedding anniversary. Since I don’t speak Hungarian, I pasted the text of the article into Google Translate and cleaned up the result with additional help from a Hungarian relative:

A trio of gold. Last Sunday there was a very interesting celebration in our town in the Mercur Hall. There were three siblings in gold: 71-year-old Sámuel Goldschmid and his wife, 66-year-old Sarolta Burger; 78-year-old Bernát Goldschmid and his wife, 68-year-old Regina Koritsoner; and 74-year-old Árón Steiner and his wife, 79-year-old Netti Goldschmid. All three couples married in January 1826. On this golden anniversary there were 7 children and 30 grandchildren and 2 great-grandchildren behind Sámuel Goldschmid; behind Bernát Goldschmid there were 9 children and 28 grandchildren. Árón Steiner had no children… On this occasion, Sámuel Goldschmid’s Granichstätten nephews from Vienna presented him with a silver cup of value about 300 f.

My great-great-great-grandfather was the Sámuel Goldschmid of this newspaper article. The article, although short, is a goldmine of genealogical information about his family. It revealed Sámuel‘s brother Bernát Goldschmid and sister Netti Goldschmid, and that allowed me to merge my family tree with an existing family tree for Bernát Goldschmid that was on the collaborative genealogy website Geni. Since Netti died after 1895, when Hungary began requiring civil records for life events, it was easy to find her death record on the Family Search website, which provided her father’s name, Náthán Goldschmid. I had not known the names of either of Sámuel‘s parents (my great-great-great-great-grandparents) prior to this. Here is what I knew about this ancestral family after a little more digging for dates:

Náthán Goldschmid’s children:

- Netti Goldschmid, 1793-1896

- Bernát Goldschmid, c. 1796-1877

- Sámuel Goldschmid, c. 1800-1889 (my g-g-g-grandfather)

- ?Granichstätten?

The newspaper article stated that, at the time of writing in 1876, Sámuel had thirty grandchildren (I know of only eleven alive in 1876) and two great-grandchildren (I know of none alive in 1876), so this provides me some very concrete and challenging research goals.

But the most intriguing part came in the last sentence of the article. It mentions Viennese nephews with the surname Granichstätten, a name that was previously unknown to me. Searching around on Geni, I eventually found a Franziska Granichstädten (slight spelling variant), born Goldschmidt (ditto) circa 1792 in Pápa, Hungary, where my Goldschmid family lived. She moved to Vienna and had eight children, who could have included the nephews that sent the silver cup mentioned in the last sentence of the newspaper article. Franziska would have been approximately eight years older than my great-great-great-grandfather Sámuel, so could easily have been his sister. She died long before the 1876 newspaper article, which explains why the silver cup would not have come from her but rather from her children. The facts that her birth name was Goldschmidt, that she originated from Pápa, that her married name was Granichstädten, and that she had children in Vienna all fit the last sentence of the newspaper article so beautifully that Franziska Granichstädten seemed a very likely sister of Sámuel Goldschmid. But this all appeared to be circumstantial evidence.

What I needed as the capping evidence was some document that listed Franziska’s father’s name as Náthán, the name I now knew to be Sámuel’s father’s name. I found Franziska’s death record in the Vienna Jewish Register on the Family Search website, but unfortunately it did not include her parents’ names. I found most of her children’s birth records, but again they did not include Franziska’s parents’ names. I could not find any newspaper obituary or birth announcement for Franziska. What I really wanted to find was the record of her marriage to Albert Granichstädten, which would surely list their parents’ names.

I conjectured at the time that Albert Granichstädten and Franziska Goldschmidt were married in Budapest around 1815. This prompted me to post a question to the Facebook group Zsidó Múlt->Családkutatás, which supports Hungarian Jewish family research, asking where I could find Budapest Jewish marriage records from 1815. The disappointing answer I received was that Jewish records in Hungary before 1850 were rare, as there was no law requiring such records to be maintained. A search of the Vienna marriage records online also proved unsuccessful. Lacking Franziska’s parents’ names from a birth, marriage, or death record, Esther Toth from that Hungarian Facebook group suggested I locate Franziska’s gravestone, as the inscription might provide her parents’ names. Her clever suggestion seemed to hold my last hope.

Franziska died in 1842 and is buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Währing, Austria. That cemetery closed in 1879 and has fallen into extreme disrepair due to toppling trees, upheaval by roots, overgrown plants, excavation during the Nazi occupation, and vandalism. Entry to the cemetery is now by permission only. I feared that her gravestone might have been destroyed or at least have become unreadable, and posted an inquiry to the mailing list of the JewishGen Austria-Czech Special Interest Group.

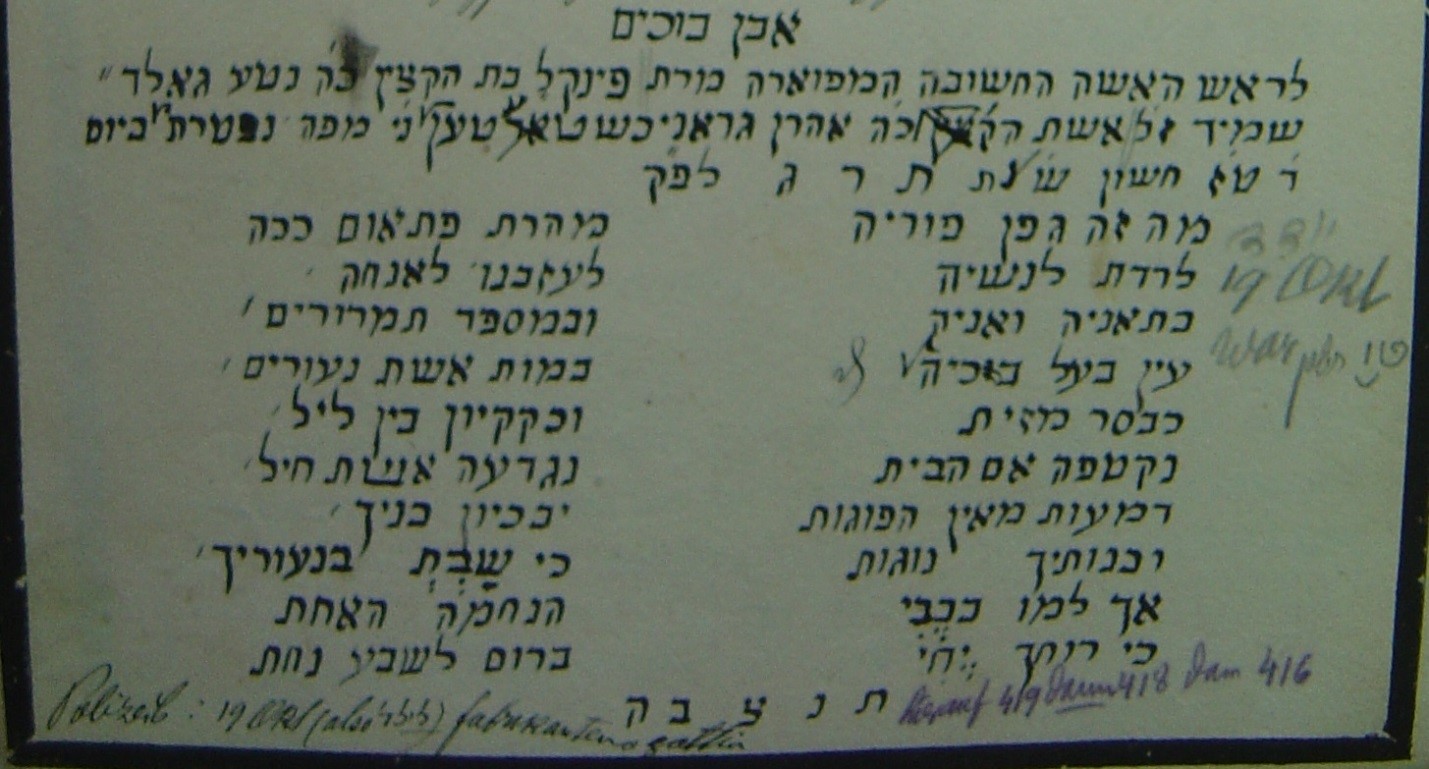

Wolf-Erich Eckstein, archivist of Vienna’s Jewish Community (IKG), replied to my post, reporting that the gravestone was indeed unreadable when he photographed it in 2000, another disappointment to me. To my great surprise, though, he told me that there is a partial inventory of the cemetery’s inscriptions: “Around 1905 Dr. Pinkas Heinrich, the archivist of the Jewish Community, founded an inventory about the graves he found … He included parts of the Hebrew inscription from the headstone[s].” Fortunately for me, Pinkas Heinrich had chosen to include a transcript of Franziska’s gravestone, an image of which was sent to me by both Wolf-Erich Eckstein and Randy Schoenberg.

Franziska Granichstädten’s

Gravestone Inscription

(click to enlarge image)

I cannot read Hebrew, but a few people kindly provided translations, including my friends Dvora and Dov Harel. They reported that the inscription states Franziska was “daughter of the officer Neta Goldshmid, blessed be his memory”. At last I had Franziska’s father’s name! A little more searching revealed that the name Neta is often a Hebrew alternative form of Nathan, my great-great-great-great-grandfather’s name (Náthán Goldschmid). I had finally accumulated enough evidence to convince me that Franziska’s family tree and my family tree could be joined.

One part of my obsessive persistence to connect Franziska Granichstädten to my Goldschmid family was that she had a large, far-flung, and influential family on Geni. Several members of the Granichstädten family appear in Wer Einmal War, Georg Gaugusch’s treatise on the most influential Jewish families of Vienna during the period 1800-1938. Another curiosity for me is that, while Albert Granichstädten had married into my father’s Hungarian family, his cousin’s great-granddaughter, Anna Luise Granichstädten, had married into my mother’s Viennese family. I would never have noticed this odd coincidence had it not been for the unusual surname that had caught my eye in this 1876 newspaper article.

It will be obvious that I had much help in this research from friends and collaborators in many quarters. I am grateful to all of them.

February 2019

Seattle, Washington, USA

Editor’s Research Notes and Hints

Martin’s story demonstrates excellent use of a variety of online resources, networking with other researchers, and diligently following the trail until he found success.

- A

tip Martin received from a fellow researcher led him to the Hungaricana

website, where he found the 1876 article regarding his

great-great-great-grandparents. - Using Google Translate , he translated the Hungarian article. Another excellent resource for translations is JewishGen’s ViewMate

- Martin found mention of Franziska, who he thought might be the sister of his great-great-great-grandfather, on the Geni website.

- He then discovered Franziska’s death record in the Vienna Jewish Register on the Family Search website, but still lacked the name of her father.

- A suggestion from a researcher on the Zsidó Múlt->Családkutatás Facebook page that focuses on Hungarian Jewish family research led Martin to look for Franziska’s gravestone to find her father’s name.

- He located her gravestone in the Jewish Cemetery in Währing, Vienna, but feared that the inscription had faded beyond readability.

- Martin then posted an inquiry to the mailing list of the JewishGen Austria-Czech SIG . A response to his post from an archivist at Vienna Israelite Community IKG led him to a 1905 inventory of the gravestones.

- Martin

found the Granichstädten family included in Georg Gaugusch’s

treatise on influential Jewish families titled Wer Einmal War.