by Shelly Sanders

One is not truly dead until one’s name is forgotten. Talmud

My great-grandparents were forced from their home in Riga, Latvia — out of their culture to such a degree that their Jewish heritage was concealed from future generations. My grandmother, Shelly Talan Geary, hid her faith when she moved to Canada, a decision that rippled through generations that followed, and diluted our Jewish culture. I had no idea about my Jewish genes, or how my grandmother got to Siberia, or that she had relatives in Riga and visited them several times, as recently as 1929, then lost contact during the war. That almost all of them were imprisoned in the Riga ghetto, then killed in the Rumbula Forest massacre. That she had no contact with her mother, sister, brother, and nephew, who were in Shanghai during the war, and wasn’t sure that they were even alive.

All of this I discovered in the last several years, through old daguerreotypes and the Internet, using four online resources: JewishGen.org, Ancestry.com, Riga Ghetto and Latvian Holocaust Museum, and the Latvian Surname Project.

My biggest coup was finding the existence of my great-grandfather Max’s younger brother, Jossel Talan. My biggest disappointment was finding that Jossel, his wife, and two children (21 and 15 years of age) were killed in Riga during the Holocaust. I was struck with pangs of grief for people I didn’t know, yet were blood relations. And my mind jumped to my grandmother; had she ever met her cousins, aunt or uncle? Did she know how and when they died? I went off on a tangent, delving into the Latvian Holocaust which cut the Jewish population from more than 93,000 in 1939 to 2,000 in 1945. I was overwhelmed by anger and nausea when I read about the Riga ghetto, and the two “Aktions” carried out by Latvian and German soldiers, leaving approximately 30,000 Jews dead in the Rumbula Forest on the edge of the city.

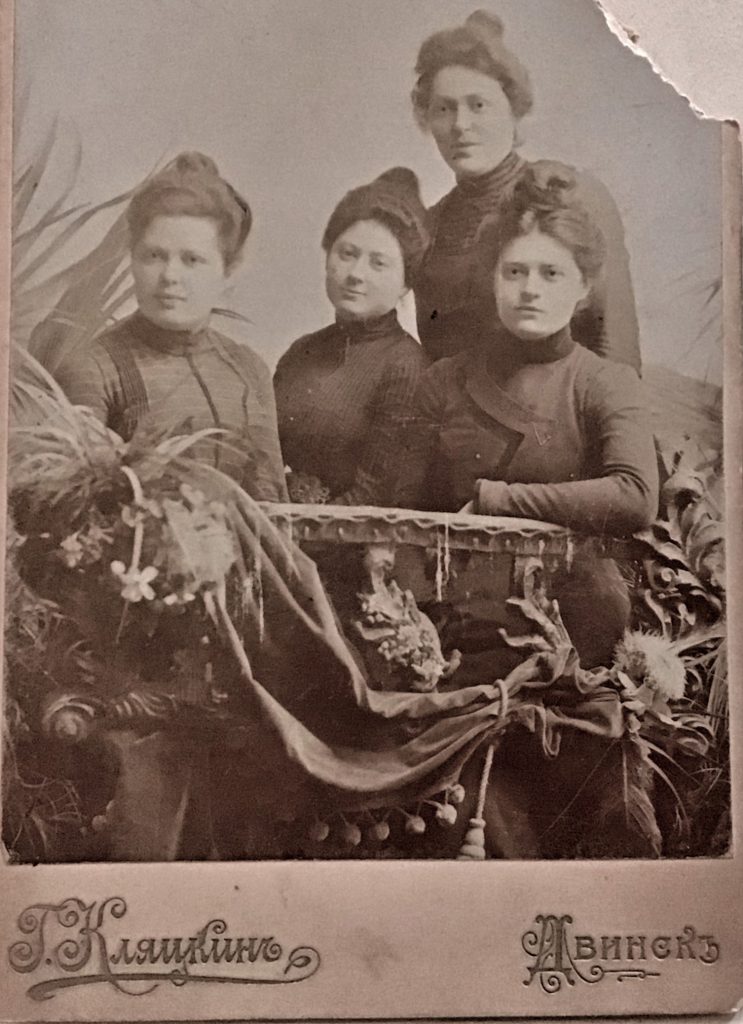

The more I dug up, the more I wanted to know. The names and fates of my great-grandmother’s sisters, posed in a formal portrait. The name of Miriam’s husband, my maternal great-great grandfather. The fate of the male cousin, Laza, seated beside my grandmother in photos taken in Riga in 1913 and 1929. What Jossel Talan looked like. Why my great-grandparents (Sophie Presmann and Max Talan) went to Siberia, of all places, where my grandmother and her two siblings were born. Unable to find the answers online, I booked a trip to Latvia in October 2018, eager to walk in my ancestors’ footsteps, and determined to uncover the information I needed to fill the blank spaces in my Jewish family tree.

The day I landed, I met with the director of the Jews in Latvia Museum, Ilya Lensky, born and raised in Riga. The museum, which once housed a Jewish club and Jewish theater, was impressive with its columns and intricate details on the exterior, and its high ceiling and sweeping staircase inside. Under the Nazis, the building became a soldier’s club and theater, and when the Soviet occupation began in 1944, it was the House of Political Education of Communist Latvia. As soon as we sat down, I asked Ilya if he knew why Latvian Jews, like my great-grandparents, ended up in Siberia.

“Because your great-grandparents were married and exiled in 1905,” he began, “it is most likely they were involved in the Bolshevik Revolution and exiled. Their marriage was probably expedited so that they could both go to Siberia.”

I was stunned. And a little proud, thinking of my great-grandparents rebelling against the Tsar. This one new revelation made Sophie and Max seem more real. It made me feel part of something larger than myself.

Ilya went on to explain that there was a demonstration in Riga on January 13, 1905, which turned into a massacre. Seventy people were killed. This would have been the event leading to my great-grandparents’ exile.

Anti-Semitism underscored Latvian society in the early 1900’s, when it was almost impossible for a Jew to get a position in public service. In all of Latvia, Ilya said, there was just one Jewish policeman. In addition, there were official limitations on Jews enrolling in universities during the late 1930’s.

In the 1897 Russian Census records I’d found on JewishGen, Max was identified as a merchant of the second guild. Ilya told me that merchants were divided into three guilds, with the third being the lowest. Most Jews were in this guild and could trade only within the borders of provinces. Second guild merchants traded throughout the empire, while first guild Jews were able to trade internationally.

I asked Ilya if he could give me the modern street names for Max’s address, as well as his brother and father’s. Not only did Ilya know them without having to look them up, he also said they must have been trading something lucrative, like timber, because they both lived in wealthy sections of Riga.

Eager to see for myself, I took a cab to 2 Avotu iela, where Max Talan lived before he was exiled. The building was old but had been restored, with an ugly, modern façade on the street level. I looked up and saw the original red brick that Max would have seen, on the upper levels, and was struck by the fact that I was standing in the very spot he would have stood more than a century ago. Max was becoming more than a black and white face on a photo.

Jossel Talan, Max’s younger brother, lived nearby, at 20 Elizabetes iela, a deep yellow-terraced house with white trim and intricate ornamentation. I had never seen a photo of Jossel, yet there I was, standing in front of his house. It was almost too much to process.

The next day, I ventured to the Latvian National Archives in Riga where I’d sent family information a couple of months earlier. A pile of old albums and documents had been placed neatly on a table, with my name on top. The only problem was that everything was written in either Russian or Latvian. And the stern-faced archivist made it clear she didn’t have time to translate, though she did say the people she’d included were relations of mine.

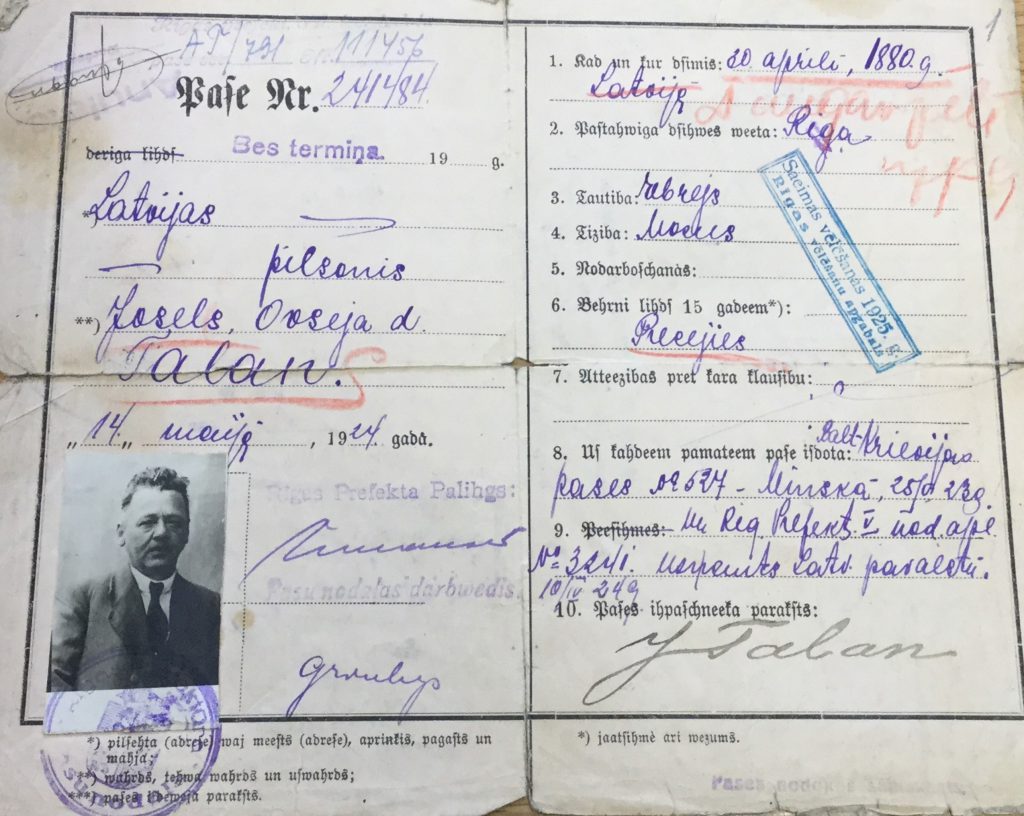

I waded through pages with photos of strangers, passport stamps, and Cyrillic text, able to pick out a few handwritten names. Schlomo, Ruven, Jossel. My great-uncle. For the first time, I saw his face and recognised my grandmother and her brother in his features. It was mind-boggling, like finding out you’ve won an award. Only better. And it spurred me to look closer at the rest of the documents, for Jossel’s wife and children. I found nothing but his wife’s name on his identity card.

On my third and final day in Riga, I visited the Ghetto Museum, located on the site of the former Jewish ghetto. Before entering, I asked the attendant if he could look up the address where Jossel and his family lived in the ghetto. The ghetto house was smaller than I’d imagined, its walls still covered in newspapers people used as insulation against the arctic wind. It was hard to believe even four people lived in such a confined space, let alone the more common dozen or so.

I doubted my grandmother knew her uncle and cousins were forced into such inhumane conditions. Very little was revealed about the Latvian Holocaust until the Soviets left in 1991, almost 20 years after she’d died.

The attendant said Jossel’s son, Ewsey, didn’t die at Rumbula or in the ghetto. He was seized in July 1941, along with other young, Jewish men, then forced to dig up graves of those killed by the Soviets. The Nazis photographed these Jews with the dead, and proclaimed the men had killed these Latvians. It was blatant propaganda to ignite a pogrom against the Jews. The men, including Ewsey, were shot July 21 in the central prison courtyard. Nobody knows where they’re buried. The attendant also said he couldn’t determine if Jossel, his wife and daughter were killed in the November 30 or the December 8 Rumbula massacres.

Standing under a clear blue sky, surrounded by majestic birch and pine trees, nausea rose to my throat, thinking of the horror my relatives must have felt, stripped to their underclothes, marched to a pit, and forced to lie on dead bodies, still warm. They had no funeral, there is no grave marking their lives, and nobody was left to mourn them. I put a stone on one of the mass graves and, as I left, my mind reeled with sadness and fury and a greater understanding of my obligation as heir to a precious legacy.

January 2020

Ontario, Canada

______________

*(front, L-R): grandmother’s cousin Laza, author’s grandmother Shelly Tallan, Shelly’s sister Nucia (in white); (middle row): Shelly & Nucia’s mother Sonia (with long braids), author’s great-great-grandmother Miriam Pressman (far right); other women are Sonia’s sisters.

Editor’s Research Notes and Hints

Shelly Sanders was unaware of her Jewish heritage until she was 18, and reclaimed her faith after taking Judaism classes a few years ago. Through the JewishGen Latvia Database , she found family members listed in the 1897 All-Russia Census – Latvia, Riga Passport and Travel Documents Registration, and Jewish Marriages in Riga database.

Other online resources that were helpful included Ancestry.com, the Riga Ghetto and Holocaust Museum, and the Latvian Surname Project.

In 2018, Shelly travelled to Latvia. A visit with the Director of the Jews in Latvia Museum in Riga yielded helpful guidance and information. She also visited the Latvian National Archives in Riga, where she found documents and photographs relating to her family. The attendant at the Riga Ghetto and Latvian Holocaust Museum provided additional information about the horrific living conditions in the ghetto and the mass killings by the Nazis.

Other resources helpful to those with roots in Latvia include JewishGen’s Latvia SIG (Special Interest Group) and JewishGen’s Riga KehilaLinks webpage.