by Shirley Ginzburg

When I reached

the end of my leads tracing my husband Allen’s Genirberg family, and could move

no further ahead, I was tempted to declare defeat, humbled once again by the

proverbial ‘brick wall’. There was no proof of my father-in-law’s existence in

his birth town of Dubno, western Ukraine. Of course, I knew his parents,

siblings, and extended family lived there prior to World War II. Finding a

paper trail for these kin seemed impossible.

Over the years devoted to research, I frequently faced dead ends. My maternal great-grandfather had a name so common that I was quickly rendered helpless. Abraham Shapiro is like Johnny Johnson or James Smith. On-line searches produce literally thousands of hits for names like these, unless one can winnow the number by offering up birth dates and marriage partners’ names to the data gods.

WW II, Dubno, Ukraine

My paternal side was not much easier. Grandmother Dinah Kantrowitz/Kanter (née Dalmatoffsky/DeMatoff), must have flown on angel wings from north-western Russia to Illinois a few years prior to 1900 — because there is no account of ship passage under any of several names she might have used, and no record of landing at any American or Canadian port of entry within a ten-year time span. Foiled again!

When frustration mounted with one lineage, or worse, when important details contradicted each other, I turned to my husband’s family tree. Much is enigmatic there, too. Rather than having a too common name, his was peculiarly unique.

The surname GENIRBERG existed nowhere except on documents from 1950, connected to Allen’s uncle and cousins as they sailed to America. I consulted Dr. Alexander Beider’s Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire, and tried every crazy spelling and misspelling on various global search engines. I used the Russian, Yiddish, Hebrew, English, and Ukrainian spelling options. Nothing remotely useful turned up.

But I am persistent. My husband and I approached the Dubno town historian in person during a visit a dozen years ago, and were told that any civil documents prior to WWII were pretty much destroyed over time. Fire and flood, war and neglect had taken their toll. Then, too, records might be held in Warsaw or Rivne or as far away as L’viv, but not indexed or translated. We were hoping for public records listing the citizens who paid taxes, the military conscripts, business owners, births and deaths, information that could have helped us trace the footsteps of the Genirbergs. Without civil records, church records, even tombstones, it is as though these people never existed.

Dubno, Ukraine

We left empty-handed and demoralized. We needed a miracle.

Recently, that miracle landed on my computer screen with a truly uninspiring title: “Polonnoye Area Document Project Results”. Translating these documents was a project of JewishGen’s Ukraine SIG (Special Interest Group). Earlier, I had made a donation to support these translations and, as a result, was rewarded with a document listing the translated data to date.

This particular document included over 2,000 surnames of children enrolled in Jewish schools. It covered seven different towns, spread over many square miles, including Dubno! That caught my interest. After scanning the first 75 names, I paused to catch my breath. Mining this text was not going to be easy.

It was clear that multiple translators with varying degrees of proficiency had tried their best to recreate the trove of documents into English. They were interpreting Old Russian script (no longer used) and the Hebrew alphabet. Some of the English entries were pocked with question marks, indicating that either whole words or letters were missing, illegible, or puzzling for some other reason. I could tell that the Hebrew lettering was actually not Hebrew, but Yiddish, the spoken language of the Jews in this area. This did not make things any easier for the translators. In Yiddish, vowel sounds vary greatly depending on the dialect spoken, and in this case written, by the individual authors of the original document.

Dubno, Ukraine

My heart went out to the modern scholars trying to decipher script penned with a feather quill and ink faded with age, lettering that resembled chicken scratches more than text. The document was dated 1846. This is the earliest original information available for this geographic region that I had ever seen in my decades-long hunt. Russia’s Alexander II had just freed the serfs. Tchaikovsky was an infant. In America, Iowa had just been accepted into the Union, and James Polk was President.

1846. I let that date sink in. Here was a simple list of students enrolled in grammar school, which would not have caused a stir in any cosmopolitan European city in the 19th century. But Dubno was an important, if primarily agricultural, crossroad where most of the non-Jewish population was illiterate. Nevertheless, it was important to authorities that a list be compiled of the Jewish boys being taught to read. In April of 1846, with additions made in September and October 1846, scribes were employed to document cheder enrollment.

The list of surnames seemed endless. I sped past two or three hundred names, passing familiar surnames, some of them known on my family tree, but common enough to be anyone’s ancestor, not necessarily mine: Epstein, Shapiro. Town names were entered willy-nilly, so I was especially vigilant when Dubno was cited. A few hundred lines later, my eyes blurred with the strain of reading, but look, more from Dubno!

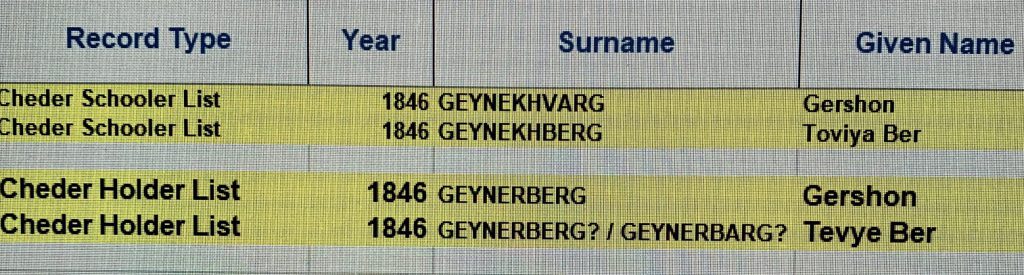

Melamed, Ganik, Kulish — no alphabetic rhyme or reason to the list. Then my mousepad-scrolling finger stopped short. It was undeniable. Two brothers, Gershon and Toviya Ber GEYNEKHVARG. Our name. Slightly altered, to be sure, but unmistakable. I yelled for Allen to come verify this was no apparition! We were elated. One of these little children could be his third great-grandfather.

click for original (see lines 7 & 8)

Were there others from this family? I forced myself to begin scrolling again, stopping at all the names from Dubno. Five hundred seventeen students later I hit the jackpot, the smoking gun that proved the family connection. Tevye Ber and Gershon GEYNERBARG were listed side by side again. This time their names were given with a spelling decidedly closer to our current version. I will spare you the linguistic technicalities, but that was OUR surname!

Luck, perseverance, patience, and a bit of knowledge on my part came together in a spectacular way. What is the likelihood that an American-born grandmother could solve a mystery that eluded everyone in her family and stretched back 175 years? About the same likelihood as that of the recent translation of a small group of papers dated 1846, for the region which included Dubno, specifically mentioning a pair of brothers, or possibly cousins, with the most obscure surname imaginable.

August 2019

Aptos, California, USA

Research Notes and Hints

Records acquired by JewishGen’s Ukraine SIG , and translated by JewishGen volunteers, provided the breakthrough Shirley was looking for regarding her husband’s Genirberg family. Because she had donated funds for this project, Shirley received an advanced index of the translated documents. These translations will eventually be included in JewishGen’s Ukraine Database . We encourage others to volunteer their time or donate funds to JewishGen’s general fund or specific projects.

You can learn more about Dubno from JewishGen’s Ukraine SIG town page and the Dubno Yizkor Book .

Shirley consulted Dr. Alexander Beider’s Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire as part of her family name research. For information on the revised edition of this classic work, published by Avotaynu in 2008, you can read a review on Avotaynu Online.

Sam Genirberg, an uncle of Shirley’s husband, is the author of the book Among the Enemy: Hiding in Plain Sight in Nazi Germany.