By Elizabeth Rynecki

[This story was excerpted with permission from the book Chasing Portraits: A Great-Granddaughter’s Quest for Her Lost Art Legacy by Elizabeth Rynecki. Copyright © 2016, published by New American Library.]

I was born in San Francisco on a summer day in 1969, just over 25 years after my great-grandfather perished in the Holocaust. My life began in a modern hospital with the prospect of a war-free childhood. Until I was forty-five I had never visited Poland. I tell you this to emphasize the fact that I am not a Holocaust survivor; I cannot bear witness to a past I did not personally experience and which seemed distant and tangential to me. I am, however, distinctly connected to the history of the Holocaust through the legacy of my great-grandfather’s art.

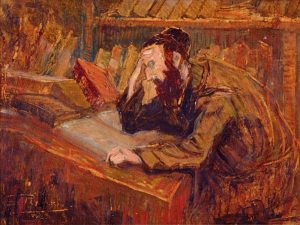

I grew up with many of my great grandfather’s paintings on the walls of my childhood home. Moshe Rynecki (1881-1943) painted scenes detailing the everyday lives of Polish Jews in the 1920’s and 1930’s. His depictions of woodworkers, water carriers, women sewing, men studying the Talmud, even street performers, were the background of my childhood.

Moshe was a prolific artist whose work was exhibited in Warsaw and featured in a number of newspapers (both Polish and Yiddish) in his lifetime. Although he was known in Warsaw before the Second World War, he was not particularly famous.

Moshe was never supposed to be an artist. He had been born into a religious Jewish family in Poland, and painting was not on the short list of acceptable career options. My great-grandfather didn’t care. He loved to draw and paint, even if it got him in trouble, which it sometimes did.

Moshe eventually grew up and left home. He lived in Warsaw, in a non-Jewish part of town and led a surprisingly assimilated life. He and his wife, Perla Rynecki (née Mittelsbach), ran an art supply store. To be fair, Perla managed the store and family life, while Moshe went out into the world to paint. He painted constantly. By the time the Nazis invaded Poland on the first of September in 1939, he had painted more than eight hundred artworks and sculpted a number of pieces as well.

Moshe continued to paint after the Nazi invasion, but as conditions for Jews worsened, he became worried about protecting his body of work. At that point my great-grandfather made the fateful decision to divide his paintings and sculptures into bundles and to ask friends and acquaintances to hide them. To those who agreed, he promised he would return after the war ended (whenever that might happen) to retrieve the bundles. Soon after, Moshe willingly went to live in the Warsaw Ghetto. His son, my Grandpa George, who lived with false papers in a Polish neighborhood in Warsaw, begged his father not to go. And when conditions in the Ghetto worsened, George offered to find a way to get Moshe out. But Moshe didn’t want to leave—he wanted to “be with his people”—and whatever happened to them would happen to him. “If it’s death, so be it,” he said the last time he ever spoke with his son.

Though Moshe was ultimately deported and murdered by the Nazis, his wife, Perla, managed to survive the Holocaust. After the war she did her best amidst the near total devastation in and around Warsaw to recover her husband’s art. Ultimately, she found only 120 paintings, stashed in a cellar in the Praga district of the city. Grandpa George wrote in his reminiscences of the war years that his mother finding them was a “miracle.” For more than fifty years, my family assumed all that remained of my great-grandfather’s collection was the work Perla recovered.

In 1999 I built a website dedicated to sharing my great-grandfather’s art. At first not much happened, but over time, with the help of information I found posted on the internet, friendships I made on social media, and the kindness of strangers, I began to find clues that more of my great-grandfather’s paintings had survived the Second World War. Sometimes I discovered accession numbers of works held by museums, but no other information; other times I found photos of the works but no clues as to the location or holders of the originals; and sometimes I lucked out and private collectors with my great-grandfather’s paintings contacted me. Of course, not everyone who had my great-grandfather’s artwork wanted to speak to me. Some were afraid of the great-granddaughter asking for pictures and information about how the paintings were obtained. Others were more generous, sending photographs of Rynecki paintings in their possession and even allowing me into their homes to see the works and interview them. As my project gained momentum, and I spoke to more people about my search, I heard from others what I’d always felt personally: not only was the story amazing, but the art was beautiful.

There would be no story to tell if the Holocaust had not happened, but this story is less about the Shoah and more about my great-grandfather’s art and what happened to his body of work in the aftermath of the Second World War. If the paintings could speak, it would be their story to tell. But they cannot, and so I wrote this book to share my story of discovery.

I am uniquely situated to tell the Chasing Portraits story. I grew up surrounded by my great-grandfather’s paintings. I studied his art and learned to discern his ethnographic and impressionistic documentation style of Polish-Jewish life from a young age. For more than fifteen years I have researched and written about Moshe’s work to make the archival information, history, and narrative connections come alive.

Over the past several years, there has been a lot of publicity about lost and looted art from the Nazi era. While much of the recent interest centers around the astronomical value of famous artworks both lost and found, there are much greater numbers of lesser known pieces that vanished during the war, and each has its own tale to tell. Chasing Portraits seeks to tell one of those stories in order to share the rich history in the scenes my great-grandfather painted as well as what the paintings themselves represent as survivors.

June 2017

Oakland, California, USA

NOTE: Learn more about Elizabeth Rynecki and the art of her great-grandfather Moshe Rynecki on her website http://rynecki.org/ and blog http://rynecki.org/blog/