by Jeremy Frankel

At the beginning of 2019 I was contacted by someone in Perth, Australia. I will call him ‘Mitchell’. He claimed he was a cousin to me. He had taken a DNA test which proved he was 25% Jewish; though it only confirmed what he already knew. As this is a story that’s still unfolding, and because of what was uncovered, I’m not using any real names here. You will appreciate why as you read the story.

To begin at the beginning, Mitchell’s father, ‘Douglas’, was born in 1929 from a relationship between two people in London, England. The birth father was Jewish, the birth mother was not. The young woman was sent away to Brighton, on England’s south coast, where the child was born. After the young woman had given birth, her father paid to have the child kept in a “private creche” for 3-4 years. Her father then died and the woman’s mother put Douglas up for adoption. He was adopted by a couple in Manchester, Lancashire.

Sometime after World War II began, Douglas was sent out to Australia. (The adoptive parents were to follow, but both died of natural causes in the UK.) Hence Douglas grew up alone in Australia. He eventually married and had children of his own.

Douglas’ son Mitchell grew up knowing his father was half Jewish. Naturally, he knew all about his own mother’s family, but his father’s family stopped right there with Douglas.

About twenty years ago Mitchell found his paternal birth grandmother (she lived to be 102!) and was able to fill in the story about how Douglas came into the world.

Douglas’ birth mother had recalled, even after all these years, the full name of the birth father, and the kind of business that the birth father’s family was engaged in. She said that his name was Harris Koenigsberg (Mitchell’s spelling) and that Harris was in the “fur business.”

To be honest, on the one hand with 8000+ relatives gleaned from 35+ years of research, I’m not in that great a hurry to add many more. Because of this, I’ve not really paid much attention to reviewing DNA results and seeing who might be a close relative. Except that “close” is a relative term. (No pun intended!)

My two brothers and I have a slightly unusual situation. My father was an only child, and my mother’s brother never married. Hence we have one uncle, no aunts, and no first cousins.

That said, (deep breath) my father’s mother was one of seven children, all born in England. My father’s father was one of ten children, all born in England. My mother’s mother was the youngest of nine, all born in Poland, but apart from the oldest who married in Poland, the other eight all married in England and all nine had children in England. Finally, although my mother’s father had but one brother, the two of them had twenty-three first cousins; yup, all born in England.

On the one hand I’ve had a relatively easy time researching all my English cousins, and why it is I have a very, very large, extended family, and much of my research has been focused in England.

On the other hand, I know very little about much older branches who were in Poland and Lithuania, because the branches of my family who left, did so between the 1840’s and 1880’s.

Because of this luxury of spending a lot of time researching my family in England (plus the odd branch in America), I’ve not really given much thought to possible cousins who could be discovered from DNA testing.

It was quite a surprise when ‘Mitchell’ contacted me to say “hi, I’m your long-lost cousin.”

Knowing his paternal birth grandfather’s full name allowed Mitchell to engage in some creative sleuthing. This led him to email me in January 2019:

“Hello Jeremy,

My name is ‘Mitchell’ and I live in Perth, Western Australia. To be brief, my father was born out of wedlock in 1929 and was adopted by the XXXXX family. I found his birth mother in 1990 and she told me that my dad’s father was Harris Koenigsberg, whose family were furriers in London. Harris (or Harry as he was known to my grandmother) may be the youngest brother of Jane Koenigsberg. . .your father’s mother. . .being your [paternal] grandmother. I am just guessing at the moment that I have the right Harry Koenigsberg.”

Although I had never heard of a family story of a child being born out of wedlock, this doesn’t mean that it couldn’t have happened. Yes, Harris Koenigsberg was my grandmother’s brother, and yes, he was in the fur trade. But first I thought I would search to see if there was anyone else who might fit the bill.

I then carried out a search in FreeBMD for anyone whose first name began with “Har*”, the asterisk allows any name-ending, and a last name “Ko*igsber*”, which allows for any last name that begins with either “Kon” or “Koen” or something else, which either ends in “berg” or “berger”, for the period 1909 to 1940. It brought up only four results.

One was a woman, Harriet Koenigsberg. Two were for a Harris Koenigsberg (a death [1921] and a marriage [1934]) and one was for a Harris H. Koenigsberger who married in 1936.

The first three are members of my family. Harriet was my grandfather’s niece. The Harris Koenigsberg who died in 1921 was my great grandfather’s brother, and the other Harris Koenigsberg who married in 1934 was my grandfather’s brother and the supposed birth father of Douglas, born five years earlier.

Harris H. Koenigsberger was born in 1871, which means if he had fathered Douglas, he would have been 58 years old. Not impossible, but unlikely. Harris Koenigsberg, on the other hand was born in 1906, meaning he would have been just 23 years old, making him a much more likely candidate as the birth father.

Furthermore, Harris Koenigsberg was a furrier, whereas Harris Henry Koenigsberger was, according to the 1939 Register, a commission agent and importer.

Now, I agree that using FreeBMD is not conclusive, and it’s possible there might have been another “Harry Koenigsberg” living in London around 1929. And yes, I did check other databases, such as the 1939 Register, which itself is not conclusive as the name might have been redacted.

Now, having got this far, I was almost on the verge of getting very excited, (was it ‘my’ Harry?). There was, however, just one little fly in the ointment—Mitchell doesn’t show up as a DNA match to me. You would think at 25% he would— could he not? On the other hand (sadly), maybe his birth grandmother was mixed up as to who the birth father might have been. It would seem strange though for a gentile woman to be in some sort of relationship with not one, but two Jewish men at the same time?

With a deep sigh and the realization I had to clear my family name, I embarked on a sleuthing expedition of my own. There was little to go on other than the birth mother recalling that the birth father had the name Harris Koenigsberg. I pulled up ‘my’ Harris Koenigsberg and looked over all the information there was on him in my Ancestry tree.

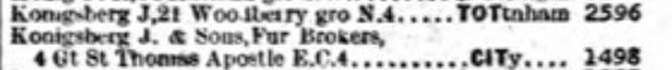

Working through his life and various documents, I got to the 1930 London telephone book. He was the only H. Koenigsberg. It was a triple-column page and as my eyes skimmed over the page I noticed in the next column an entry that read “J. Konigsberg and Sons, fur brokers.” Hmmm?

(click to see full page)

I began constructing a tree for this Konigsberg family. The Konigsberg family had seven children, the oldest being Harry Konigsberg, born in 1895. The family was in the fur business but in a subtly different way to my family. My Koenigsbergs were manufacturers of fur clothing, whereas the Konigsberg family were fur brokers. The family all lived and worked in London except Harry, who lived in New York, but, as immigration records showed, he often traveled between the two countries.

Harry married Celia Gold in 1924 (age 29) in New York. Sadly their first child, a son, born in 1926, lived but five days, and was buried in a Jewish cemetery in Queens, New York. The couple then had Naomi in London, born six months before Douglas.

Typically, when Harry traveled to England, Celia never accompanied him. However, in October 1927, when Harry traveled to London, Celia followed, arriving on 22 June 1928.

Thanks to an online conception calendar (one simply plugs in the date of birth), it will show the most likely date for conception and, if you wish to be that specific, the most likely date when (ahem) intercourse would have taken place. (I have found it to be very useful—the program that is!). It’s part of a suite of programs put out by www.calculator.net.

Hence we see that Naomi’s likely conception was 5 July 1928 (two weeks after Celia arrived in London) and she was born 5 April 1929. Douglas was born 21 October 1929, meaning his conception date was around 5 February 1929.

Putting it bluntly, Harry was not only married, but his wife was pregnant and about to give birth in two months time when he was also involved with another woman.

I then continued researching the Konigsberg family to recent times.

Naomi married in New York in 1951 and had three sons. In mid-September I reached out to the oldest one, Geoffrey, a retired CPA (chartered public accountant) in New Jersey. I explained who I was and why I was writing to him.

His first response was:

”I may be the Geoffrey Selby you are looking for. My mother’s name was Naomi Konigsberg. My maternal grandfather was named Harry and he was in the fur business in London and New York City. My mother was born in London in 1929.”

I wrote back explaining the whole “megillah” His terse response was:

”It is hard for me to believe that my grandfather had a son out of wedlock. He was ultra orthodox. If I was to agree to the DNA test, would you share the results with me?”

I told him of course I would. He never got back to me. A few days later I tried one more time with:

“Have you had a chance to review and think about what I had sent you regarding Mitchell’s research? Also, I was wondering if you are in touch with any of your English Konigsberg cousins?”

A month later I got this from Debby, Geoffrey’s cousin, who lives in England. Her email was very “interesting”.

”I’m replying to this on behalf of a family member who’s forwarded your email to me. I’ve spoken to some of our family, and it’s unlikely we’d do a DNA test to see if we’re a match for the man you’re talking about.”

I wrote back to Debby:

”It’s a little disheartening to read your response. Mitchell who contacted me is bereft of any family further back than his father because he doesn’t know who his father’s father was. He knows who the birth mother was because he was in contact with her some twenty years ago. Not knowing his father’s lineage is probably hard to live with. I have to impress that what I have surmised is but a conjecture. And yes a DNA test would probably tell us one way or the other.”

They never got back to me. I leave it to you, the reader, to draw your own conclusions.

Postscript:

I had carried out the research for “Mitchell” during the early part of 2019. He had previously taken a DNA test with Ancestry.com (as I had) and because Mitchell was 25% Jewish, if he had been related to me, then a match of some sort really ought to have shown up—but it didn’t. I began writing this up as a story for possible publication.

Mitchell made me the administrator of his Ancestry.com DNA account and on Friday, January 24th, 2020, the final piece of the puzzle slipped into place. I received an email alert from Ancestry.com that “Stuart” had taken a DNA test and was related to Mitchell, in the 3rd-4th cousin range with 157 cm across nine segments. According to the microscopic three-person tree, Stuart was one of Harry’s three grandsons, living in America.

In fact, Stuart was Geoffrey’s brother, the other grandson I had contacted who couldn’t believe his grandfather had fathered Mitchell’s father. (Did all that make sense!)

Stuart may have unwittingly taken a DNA test just for fun (who knows), but it proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that Mitchell was not only related to the Konigsberg family, but was also Harry’s grandson.

My hunch and subsequent research had been confirmed by the DNA test result. What Mitchell will do with this, I don’t know. He may now go on with his life, possibly comforted by the fact that he now knows the full extent of his father’s paternal family and who they were. He may or may not contact them, but he does now have the information.

As we have seen and no doubt read, DNA testing has now changed everything. What was once thought to be private, and perhaps a secret that could be taken to the grave, can now be retrieved from the grave.

May 2020

Sacramento, California, USA

Note: A slightly different version of this story was originally published in the February 2020 issue of ZichronNote, the journal of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogy Society (SFBAJGS). Reprint permission granted.

Research Notes and Hints

Jeremy Frankel, an experienced genealogist with an extensive family tree, responded to a message from a man who thought they might be related, a man who was searching for information regarding his biological grandfather.

Jeremy discovered several possible candidates for Mitchell’s biological grandfather from a search on FreeBMD, which is part of FreeUKgenealogy.com. He used a “wildcard search” to achieve this, where symbols such as asterisks take the place of missing letters. This is a useful search technique when unsure about the exact spelling of a name.

A search on Ancestry.com brought Jeremy to the 1930 London Phone Book, and a listing for a Konigsberg family in the fur trade — the right surname and the right trade! Jeremy created a family tree based on this information and wrote letters to some of the descendants he located.

Using the tools at calculator.net, Jeremy was able to determine the probable conception date of Mitchell’s father.

Our Jewish ancestors were an endogamous population, which means that they tended to remain in relatively limited geographical areas and marry within their own Jewish communities. As a result, Jews today may share DNA with each other not only because they share a recent common ancestor but because they share many distant common ancestors. While the DNA test results from Ancestry.com do not on their own prove the identity of Mitchell’s grandfather, the DNA results in conjunction with the other information discovered by Jeremy do provide a strong case for Mitchell and Stuart to be descendants of the same grandfather.