|

|

|

[Page 59]

by N. Shemen

Translated by Jerrold Landau

based on an

earlier translation of the Yiddish by Tina Lunson

Poland, the “Center of Spirituality”

In their long road of wandering, the Jews lived under many climates and in relation to many peoples and languages. The curse “a people whose language you do not understand” (Devarim 28:49) was realized in the most difficult manner. Jews traversed all the unpaved pathways of the world, roamed all the roads and byways, and still managed the circumstances in which they lived.

So in Babylonia and so in Arabian Spain; so in France and so in Germany; so in Italy and so in Poland – everywhere they carried their Torah and everywhere rooted their Jewish life, Jewish culture, and traditions. In each Jewish settlement, they lived and produced great Jewish personalities who not only created the societal atmosphere but, in general, laid the foundation of Jewish life.

Lublin came to be considered the cradle of the Jewish-Polish variant in Jewish history. Since the times of Kazimir the Great – King of United Poland, who broadened the “Kalisz Statute” of Jewish rights in 1334, when the massive stream of immigration into Poland began, Lublin was the town of Jewish sages, great rabbis, highly intellectual personalities, and then the town of the creator of Hasidism. In the era of the Vaad Arba Artszot [Council of the Four Lands], Lublin was its main meeting place.

Without even peeking into Lublin's historical horizons here, we will, out of necessity, note just a few lines from the sunny era in the history of Lublin, kaleidoscopically glancing at the colorfulness of each magnificent epoch, at least from the era of Rav Yaakov Polak until the MaHaRa”M, when the web of Jewish culture and tradition was being woven in Lublin, and when there was a very strong pulse of Jewish life there. Even then, Lublin had its own Jewish press, where the most important holy books of the time were printed. That was a time of Jewish intellectual ferment, our most notable renaissance era. A sunny time-period that enriched the Jewish world with colorful, important Jewish personalities, among whom the personality of MaHaRSha”L beams out – the author of “Yam Shel Shlomo” and “Chochmat Shlomo”, with his commentaries on Jewish halacha, on the Talmud commentators, on the Polish manner of Judaism, on the formation of the countenance of the Jewish settlement in Poland, which was, in the epoch of MaHaRSha”L, the dominant Eastern European – and to some extent also Western European – center.

Lublin, as is known, is among the oldest Jewish cities in Poland. Lublin is, as mentioned, the city of the Council of the Four Lands, the city of great rabbis, the city of Chasidus, of the Chozeh [Seer] of Lublin and of the Eiger-Kohen dynasty; the city of the famous world-yeshiva, Yeshivat Chachmei Lublin; the city that, until 1939, spun the golden thread of the glorious past. Now the structures of that one-time Jewish spiritual creativity are destroyed, and that former ascent lies there hacked down, a ruin. Abel's blood cries out from Hitler's “rezervat” [reservation], and we must make do with memorial anniversaries for the liquidation of a great, long-established Jewish settlement. But we are not wailing lamentations. As the poet Avrom Lev of Israel wrote in his poem “To My Remaining Brothers in Poland”:

“My song to you, however small it is, however weak,

my word will meet so many graves near you

[Page 60]

that a fear seizes me and my pen, for the pain that you experienced and saw.

How unfortunate now is my word for your horror,

how ordinary the sound of my words in my mouth.”…

I will contribute in a very different style to the memorial of the town with this monographic work about the famous Lubliner, Rabbi and Rosh-yeshiva, the MaHaRSha”L may his sainted memory be for a blessing.

Birth and Life's Journey of MaHaRSha”L

Rabbi Shlomo Luria Ashkenazi, as was his full name, was born in Pozen (Poznan) around the year 5470 (1500). His father, Rabbi Yechiel, was a famous expert in Torah and the son-in-law of the then well-known Gaon Rabbi Yitzchak Kloyber, who had migrated from the town of Worms (Vermeiza) in the Rhineland and settled in Poznan, which at that time was known as a Jewish town. The younger Reb Shlomo remained at his grandfather's house in Poznan, where he developed his genius.

The lineage of the MaHaRSHa”L stems from Rashi [1040–1105 CE] who lived in and was active in Worms, and from other sages of France, the Baalei Tosafot [Tosafists] and their successors. Rashi was, according to the reckoning of the genealogical books, the 33rd generation from the Tanna [Mishnaic sage] Rabbi Yochanan HaSandler, who was the 4th generation from Rabban Gamliel the Elder, the grandson of Hillel HaNasi, one of the heads of the Sanhedrin who stemmed from Shefatia, a son of King David. The MaHaRSha”L was given the name Shlomo after his grandfather reb Shlomo Ashapira and the last name after Rashi, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki.

He acquired much from his grandfather. He expressed this with the finest words of praise: “The pure, the Chasid, the poor one who fears G-d, the man of peace, our rabbi, Rabbi Yitzchak Kloyber.” He speaks about his wonderful grandfather with much enthusiasm for his genius and saintliness and mentions his name with unusual awe and reverence. He holds it as a privilege = to have been educated “on the lap of my grandfather,” and once signed his name as “Sar Yitzchak” (acronym of Shlomo Reb Yitzchak), and was inspired by the great and saintly one for his system of learning, comportment, and character.

In the year 5295 (1535), there was a fire in his grandfather's house, and he returned to his parents. (See “Yam Shel Shlomo” , tractate Yevamot 84, section 33; Responsa of the MaHaRSh”aL, sections 12 and 64). There he saw Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Yerushalmi Haberkasten from Ostroh (Ostrog), Podolia, who later made aliya to Jerusalem (see “Shem VeShe'erit Be'arichut” [Long–Form Version of Shem VeShe'erit]. He chose him for a son-in-law and a pupil and took him to Ostroh, which was then known as a town of Gaonim and scholars, and had the finest rabbis serving in positions of local rabbinic authority. The name of MaHaRSha”L's wife was Lipka (“Tiv Gittin” 103, section 30, subsection 3, “Yam Shel Shlomo”, Gittin, chapter 2, section 32).

His father-in-law, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman, was considered one of the Gaonim of Ostroh, which later had as rabbi of the city the MaHaRSh”A, Rabbi Shmuel Eliezer son of Reb Yehuda Halevi, who, in gratitude to his mother-in-law, was also called Rabbi Shmuel Eidel's (born in Krakow 5325 - 1565, passed away in Ostroh 5392 - 1631).

The city of Ostroh was the leading city of all Volhynia and Ukraine. The MaHaRSha”L often viewed himself as a pupil of his father–in–law, who held the title of head of the rabbinical court of Ostroh.

His father-in-law was also the head of the local yeshiva, which was under the supervision of the famous Lublin Rav and Yeshiva Head, Rabbi Sholom Shachna, an outstanding pupil of Rabbi Yaakov Polak, father and founder of “the Polish Sharpness”. Rabbi Kalman also considered himself a pupil and follower of the famous rabbinic authority --MaHar”I Isserlin (author of “Terumat Hadeshen”) via his rebbe, the chasid Reb Daniel, as it was recorded in “Responsa of the MaHaRSha”L (section 98). At that time great rabbis and Gaonim lived and were active in the various Polish-Ukrainian cities, such as Rabbi Eliezer Ashkenazi (author of “Maaseh Hashem”, “Yosef Lekach”, and other books) in Posen [Poznan]; Rabbi Yosef Katz (author of the book “She'erit Yosef” and other books, brother-in-law of the Rema) in Krakow; the Rema, Rabbi Moshe Isserles (passed away 5333 - 1572), the author of many books in the area of rabbinic adjudication, and the author of the Mapah – his glosses that completed the Shulchan Aruch, lived and functioned in Lublin and Krakow, and whose name became

[Page 61]

well known throughout the whole world; Rabbi Yitzchak, the son of Reb Betzalel from Ludmir (brother of Maharal of Prague, the creator of the “Golem”); Rabbi Nosson Shapira of Grodno, and very many others.

But soon the MaHaRSha”L emerged with all his genius and, above all, influenced the spiritual situation of Poland and Ukraine more than the others. The “Tzemach Dovid” (Rabbi Dovid Gans, died in Prague, 5373 - 1613), an outstanding pupil of Rema, thanks to whom he learned sciences and cemented his historic work, wrote about MaHaRSha”L with these inspired words: “A great and renowned Gaon, the great illuminator, the crown of Israel, the portent of the times, according to whose light will the people of our nation go… and his name goes forth throughout the world. He taught many students, influenced the people of his generation, and authored his great work on all Talmudic topics. There is no match to his greatness, depth, and sharpness. He called this work “Yam Shel Shlomo” and he also authored the book “Chochmat Shlomo”…

Rabbi Yehoshua Falk-Kohen, author of the well-known halacha book “Sema”, elucidations on the four parts of the Tur Shulchan Aruch under the title “Drisha U'Prisha” and other books (died in Lvov, 5374 – [1614]), wrote about his rabbis, the Rema and MaHaRSha”L: “I studied at the gates of the Rema, and then I entered into the insides of the holy sanctuary of the MaHarSha”L” (see the introduction to “Sefer Meirat Einayim”, Rabbi Falk). The Rim (Rabbi Yitzchak Meir, the first Gerrer rebbe, 5559-5626 – 1799-1866) marveled greatly at the language.

As a sharp man in learning and in grasp, in creating a new system and a new method of understanding and analyzing the Rishonim [Early halachic authorities] as well as a keen man of truth, a person who hated flattery, hypocrisy and compromise – the MaHarSha”L provoked opposition against himself, polemicizing with the harshest words and biting sarcasm, from many of the great sages of his time.

The MaHaRSha”L was not a submissive person. As it seems, he could dislike a person if he was not in accordance with his spirit. He was far from calmness, equanimity, and deliberation; he was also not overly careful regarding insinuating words during a debate, and thus provoked anger from many great figures. Therefore, he had to move from one city to another, never finding much respite. He wrote about himself:

”And I am a wanderer in the land, and the breaches outweigh what still stands.” In times of great hardship, when he found himself in bitter circumstances, he would speak sharply against his enemies: “And I say that one who acts not for the sake of Heaven will find his face blackened like the underside of a pot.”

In his polemics, he used fine, flowery language, which he liked very much, and was an artist in creating paraphrases. He expressed this about one of his enemies:

“Since I have heard that one of the coarse fellows has dared to precede me –

a man who dons a coat of many colors and imagines himself standing among the myrtles –

and who composes secret scrolls against me,

never restraining his transgression amid his torrent of words,

and who declares: ‘Such matters incline toward arrogance,’

though he himself is nothing but a wild myrtle,

and wraps himself in a tallis that is not his own,

and lets his presumption rise to its full height

in the very chamber where he was conceived,

which rests upon his own anger and wrath.”[1]

Such curt, if fancy language, awoke more ire from his opponents, and as far as he could not flee the fire of controversy, it chased after him, not giving him any rest. And notably, many of his pupils were unable to adjust to his way of study and joined his enemies. That broke him deeply, causing much pain, knowing and believing that the truth was with him and that his method was the true one and the most logical.

The sole pleasure and the only comfort he had was sitting and studying and the founding of yeshivas, wherever he found himself. So MaHaRSha”L – being the official rabbi of the city in 1552 in Brisk, then called “Brisk d'Lita” [Brest Litovsk] – established the local yeshiva, and did the same in Ostroh, where he headed the yeshiva for a certain time.

At age forty, in the year 5310 (1550), he was accepted as Rabbi and principal of the yeshiva in Ostroh, taking the office of rabbi from his father-in-law, Rabbi Kalman, who then became the head of the rabbinical court in Brisk d'Lita. During the time he was involved with the yeshiva, he greatly enlarged it, broadened and changed the program of study, especially the method introduced by the Lubliner Rov, Rabbi Sholom Shachna, which was the method of his rebbi, Rabbi Yaakov Polak. About the latter, it is said that when his pupils once removed several pages from the Talmud that he had been studying from, he did not even remark about it, but with his keen and deep pilpul [dialectical analysis]

[Page 62]

connected the separate subjects. The MaHaRSha”L was against that pilpul methodology, not taking into account the opposition from those strong hangers-on of the Lublin Rov, as well as the Ostroh Rov, of whom many important figures referred to as MaHaR”Sh MeOstroh. He was then officially made the general Rabbi of all Volhynia.

After the passing of his father-in-law, he became the leading rabbi of Brisk, and many rabbis began calling him Rabbi Shlomo of Lita. He did not stay there for long. In the year 5319 (1559), he arrived in Lublin as the leading rabbi, replacing Rabbi Sholom Shachna. The son of Rabbi Sholom Shachna, Rabbi Yisroel, remained in his father's office only as the head of the yeshiva, as the “Tzemach Dovid” states it (Section A, p. 56).

The well-known scholar and cultural researcher Reb Sh. Y. Fine, the author of “Ha-Otzar”, in his book “Kirya Ne'emana” [Faithful City], is of the opinion that Rabbi Yisroel fully succeeded Rabbi Shachna, as rabbi and yeshiva head. The Serotsker Rav, Rabbi Yosef Levenstein, a significant authority in the area, advises that the “Tzemach Dovid” is correct. However, it was the MaHaRSha”L, who turned out to have disputes with Rabbi Yisroel, and suffered greatly from it. According to one version, he then built his synagogue – the famous Lublin MaHaRSha”L Shul – so he would not need to be together with his opponents. The shul measured 368 ells (amot) in length and 32 in width – a total corresponding to the gematria of lulav.

The MaHaRSha”L passed away in the year 5334 (1573) in Lublin, having been the leading rabbi of Lublin and the vicinity for fifteen years, and famous in the Jewish world as a great authority.

Shlomo Boruch Nisenboim, in his book “The History of the Jews of Lublin” (Lublin, 5660 1899), has, as usual, a separate chapter on MaHaRSha”L, and he ends that chapter in a sentimental, poetic way. We will cite a few of his words in Hebrew: “Passed away (The late MaHarShA”L) – in our city, and the cemetery merited to receive such a pure, holy body. With his death, the gushing wellspring of living waters, clear and pure, to quench the thirst of his many students. This is how his gravestone laments, a stone from the wall cries out in bitter lament, for the mighty of the mighty, and the Gaon of Gaonim has fallen.” He conveys the style of his gravestone, which is noted in many historical works:

Here lies buried

the mighty one of the mighty,

the king of all sages and teachers,

strong as a Sinai and an uprooter of mountains.[2]

The great luminary that lit up Israel for generation afte

r generation,

Through his book “Yam Shel Shlomo” and other commentaries

His name is known to the ends of the world, in all the gates.

He disseminated Torah and educated many pupils.

On the other side:

Throughout the world.

He was upright and righteous in all his cherished deeds

The Gaon (the inscription here is partially missing)… eminent, our Rabbi and Teacher

Shlomo, son of our rabbi and teacher Rabbi Yechiel Luria of blessed memory,

He was summoned to the Heavenly Yeshiva of religion and halacha on the day of 12 Kislev [the year of Nafla Ateret Rosheinu ו” כ” ב” ה” מ” נ” ו” (That means 5334 – gave up his soul), pure, in accordance with our dating system. May his soul be bound in the bonds of eternal life.

The grave of MaHaRSha”L is located in the old Jewish cemetery in Lublin, not far from the grave of Rabbi Shlomo Shachna. The gravestone stood over his grave for three hundred years; only in 1876, when the old stone was already broken and worn thin, was a new one put in place. In his passing, his pupils saw the departure of the sustaining pillar of Ashkenazi Judaism, the profound creator and translator of Talmudic logic, Talmudic philosophy, and jurisprudence.

[Page 63]

The Order of Learning Torah in the Polish Manner

and the Innovation of MaHaRSha”L

Poland became a “lodging-house of Torah” after the Spanish expulsion. But there is a great distinction between the huge cultural center in Spain and its well-developed path, the backbone of world Jewry.

The sages of Spain were, above all, concerned with language research and literary creation. They exhibited incomparable competence in the knowledge of Hebrew and generally in the cult of the spoken and written word. Grammar and Hebrew knowledge took the primary place, and they were the pioneers in that area. It is sufficient to mention such grammarians as Menachem ben Yaakov ibn Saruq, Dunash ben Labrat, Shmuel Ha'nagid; and after them a pleiad of literary scholars and highly talented poets with their eternal works, like Shlomo ibn Gabirol, Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, and others; literary theorists, scholars, creators of philosophical treatises like the Rambam, Rabeinu Bachya, Ibn Ezra, and many, many others.

The Polish center went through a very different path of development. There, it seemed as if they were not concerned with language research or with studying grammar, and for a certain time, they neglected teaching the Books of the Prophets. There was a time in Poland when they regarded with suspicion people who were given to only studying the Tanach. People knew the verses of the Tanach through the Gemara and found them in the Gemara.

Polish scholars went over the subtleties of the Gemara's language for hours on end – because the point was not the nuanced discussion or the polemic; the point was the idea, the deep thought, brought out in allusion, through a twist, a “grimace”.

The source of that sort of learning was Old-Lublin, which, more than other Polish cities, had contributed to that style of Poland, which had been in effect for several hundred years. That pilpul method of extracting subtleties, which so affected the mentality of the Polish Jew, was created in Lublin.

Pilpul was far from systematic, logical learning. It was more of a “spicing” of sharp-pointed, shrewd insights and clever ingenuity. With the strength of the “pshetl” [a clever little interpretive twist] and the pilpul-style construction, the Polish scholar swam over the sea of Talmud and exhibited phenomenal breadth and sharpness.

The creative founder of that method, and in general of the rabbinic literature in Poland of the 16th century, was Rabbi Yaakov ben Yosef Polak, or Kopelman, known as the “Baal Hachalukim” [Master of Conceptual Distinctions]. Rabbi Yaakov founded the first yeshiva in Poland, which became world-famous and attracted pupils from all the Jewish diaspora. As an “uprooter of mountains” in the fullest sense and significance of the term, with his scholastic-Talmudic dialectic and “hairsplitting”, he won the hearts of his pupils who had come to Lublin to learn Torah. The pupils marveled at their rabbi, seeing his acuity in knowing answers through his pilpul to all the most difficult questions posed in the Talmud.

The most powerful follower of Rabbi Yaakov Polak's method of learning was Rabbi Sholom Shachna of Lublin and his son Rabbi Yisroel, who further pursued that method of casuistic hairsplitting. The most well-known of his pupils was Rema, the greatest rabbinic arbiter of Ashkenazi Jewry and the author of rare, marvelous holy books.

As the son-in-law and student of Rabbi Sholom Shachna, the Rema did not speak out against the “Chalukim”, or against overly confining pilpulim. The Rema – an expositor of a philosophical treatise, who engaged extensively with philosophy, before he wrote his book “Torat HaOlah” [The Doctrine of the Burnt Offering] – could not free himself from the Polish order in the 16th century. He followed after the spirit of learning characteristic of that contemporary Jew, also in the style and the form of expressing his thoughts.

The first of that era in Poland who came out strongly against pilpul for the sake of pilpul was

[Page 64]

the MaHaRSha”L, who distinguished himself with deep logic and systematic thought. His methodology of learning was entirely different from that of Rabbi Yaakov Polak and Sholom Shachna. He was a deep analyzer with a strong critical eye. He would criticize anyone who did not learn with clear logic, as it was supposed to be. He did not flatter anyone, even when he knew it would stir up opposition against him. He hated the dry pilpul style of learning.

The books of the MaHaRSHa”L were of a completely different nature. He did not want to be just an “uprooter of mountains”; he especially wanted to be a “Sinai”, to create order on a wide scope, based on erudition and established facts. Thus were his books “Yam Shel Shlomo” and “Chochmat Shlomo”, along with other brilliant holy books that comprise a compendium of halacha in the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud.

The MaHaRSha”L was the person with the sharp mind and the clear thought who hated spinning around with pilpul and stated so openly at every opportunity. Therefore, he evoked opposition and open enmity from the adherents of pilpul.

The persecutions against him were so powerful that he expressed it this way:

”Regrettably, with the revolt of the students who are rebelling and committing iniquity against me, relying and trusting on the power of the elderly one and his son, the Gaon, they are marginalizing me and wearing my body down…”

In great pain and distress, he begged for mercy: “Oh, let their cruel hearts of stone be turned to hearts of flesh, oh, give me the strength and fortitude to save my soul and the souls of the proper students from their hands…” In that responsum, he scolded the Rema about his indifference to the suffering caused to him by the pupils of Rabbi Sholom Shachna – a group that Rabbi Moshe Isserlis himself also belonged to.

|

|

| The oldest synagogue in Lublin, the “Shaul Wohl [Katzenellenbogen] Shul”, which is named after the Jew who was, according to the legend, King of Poland for 24 hours. |

[Page 65]

Just as he was an open-hearted person who hated flattery and hypocrisy, so he also hated quarrels and ran away and hid from discord. As Horodetsky asserts, he built the MaHaRSha”L Shul so that he could avoid his opponents. Many times, he remained silent to gratuitous criticisms against him and hid out in his Beis Midrash, within his own four ells of halacha.

One of the later cohorts of MaHaRSha”L's followers in Grod and in Ostroh was the MaHaRSh”A (born in Krakow 5325 - 1565, died in Ostroh 5392 - 1631), who was active during the first half of the 17th century, and came to be considered one of the finest Jewish figures in contemporary Poland. Rabbi Shmuel Eliezer – or Reb Shmuel Eidel, as he was called after his mother-in-law's name – with his profound explications of the Talmud, wanted to make the study of the Talmud easier. Still, he made the study even harder with his knotty questions, his “kal–lehavin's” [his frequent ‘it is easy to understand’ remarks], and his “yesh–leyashev's” [his characteristic ‘one can resolve’ formulations], and sharp-minded analytical remarks. But even he spoke out against the so-called hairsplitting specious arguments, as he called them in his “Chidushei Agadot” (Bava Metzia 84): The residents of Babylon may have been of the pilpulistic sort, as we see them today. He who knows more about “vain pilpul” is praised more… Therefore, they are not able to make clear halachic decisions… Such pilpul-study confuses a learner, tears him away from the truth… (See Horodetsky: “Shem Shmuel”, history of MaHaRSh”A).

Nevertheless, in his book “Chidushei Halachot”, MaHaRSh”A cannot completely free himself of the pointy dialect of the sharp pilpulist, just as the MaHaRSha”L cannot free himself in his own books.

It was not only they themselves spoke against “pilpul for the sake of pilpul”, which was meant to sharpen the minds of the pupils (“lechaded et hatalmidim). As the “Tsemach Dovid puts it, that style of teaching was not accepted by many of the wise and righteous.

Rabbi Chaim Betzalel, brother of the MaHaRa”L of Prague, writes in his book “Derech Chaim”, that that sort of pilpul is just a lot of distortion, leads to much wasted time and incorrect interpretations in Torah “interpretations that violate halachic norms”. It would be better to spend that time learning a trade or playing chess.

Other significant figures, including rabbis and scholars, also opposed pilpul. Nevertheless, the MaHaRSha”L was the first to arouse public debate.

Despite his vehemence, the MaHaRSha”L was a modest and ethical person, and did not even want to rely on his own rulings, and sought agreements with some of them. We find the agreement from the Ludmir Rov in two responsa, in which he emphasizes: “The master [aluf] and Gaon intended well with this, as Moses did with the laws from Sinai, the statement of Yitzchak the son of Reb Betzalel, who lives in Ludmir.” However, he wrote well and judged well regarding the statement of Yitzchak, the son of Betzalel of blessed memory, who lives in Ludmir.

Jewish legend also relates that he asked a moral admonisher [musar-zuger] to come to him every day to admonish him. When the preacher-rebuker came, he would sit wrapped in his tallis and tremble as he listened to his admonitions. (Chid”a, Maarechet Sefarim, Reishit Chochma. In every book introduction, he began with the words: Solomon said that I shall become wise, but it is far from me… [Kohelet 7:23].

The MaHaRSha”L and the Rema – Two Types of Rabbis

In the Eastern European historical era, the Polish-Lithuanian-Ukrainian population was the dominant center of Jewish life.

The MaHaRSha”L and the Rema stood by the beginning of that cultural sphere. They were among the first in Eastern Europe to establish that pattern in Jewish life.

In Poland, as is known, the verbal dialectic in the yeshiva, the chavruta learning [paired dialectical study] in the Beis Midrash, fulfilled the role of the written word. Polish rabbis rarely published their works. So, we see that the founders of Talmud learning – Rabbi Yaakov Polak and his pupil Rabbi Sholom Shachna – did not leave behind any schools of thought, and that was not merely.

[Page 66]

a coincidence. It was intentional, carefully calculated.

Rabbi Yaakov Polak had only made glosses on the books of Rishonim. He tended toward leniency in Jewish law, especially by the passage of minor-age betrothal by which he allowed miyun [annulment by refusal of a betrothal imposed on a minor woman], saying the girl could openly declare that she protested against the kiddushin [betrothal]. She would not need to obtain a get [a Jewish divorce document].

The chief rabbi of Italy, Rabbi MaHaR”I Mintz, and other rabbis, came out against Rabbi Yaakov Polak's judgment. The MaHaRSha”L also maintained that the MaHaR”I Mintz was correct (Yam Shel Shlomo, Tractate Yevamot, chapter 13, section 17). The Rema defended and judged as Rabbi Yaakov Polak did (Haga Even HaEzer, subsection 155, section 22).

In contrast, the Rema wrote books on Jewish law with the same level of authority as Rabbi Yosef Caro, the author of “Shulchan Aruch” [Code of Jewish Law] and “Beis Yosef” on the “Arba Turim” by Rabbi Yaakov the son of the Rosh (who wrote the last book from 5282 – 5302, 1522 - 1542) and other books. In most of the points of contention between Rema and Caro, the halacha is in accordance with the Rema, whose “Mapah” was, to a large degree, a mirror of Polish mores and lifestyles. The Rema occupied the seat of honor among the creators of Polish-rabbinic literature. In his direction and creative style, he was followed by the entire cohort of commentators, including the “Shulchan Aruch” with their commentaries, analytical remarks, interpretations, and halachic reasoning. These included the Ba”ch (Bayit Chadash), Ta”z (Turei Zahav by Rabbi Dovid the son of Rabbi Shmuel Halevi), the Sha”ch (Siftei Cohen by Rabbi Shabtai Cohen), and many, many others.

The MaHaRSha”L also came to be counted among the great authors of rabbinic literature, both in quantity and in quality. Like the Rema, he held minhag [custom] sacred, which, for him, carried the weight of Torah. Where MaHaRSha”L says, in one place, “Do not abandon the Torah of your mother” (Proverbs 1:8), he means to say that the custom of one's parents carries the weight of Torah. The custom for him stood higher than the law -- not only the custom of the sages, but even the custom of porters and donkey drivers…

He was stringent about anything relating to custom, just like the Rema. For example, he was very strict about the prohibition against marrying two wives. He dismissed the RaShB”A's interpretation that the excommunication of Rabbeinu Gershom was intended only until the end of the fifth millennium[3]. If a Jew is guilty of bigamy by marrying two women, he said, “Your community already knows this from the outset, and we are empowered to rebuke you with a rod that does not draw blood. And behold, we will pursue you like a serpent that crawls upon the dust, casting venom and wrath until he repents of his wickedness. (Responsa of the MaHaRSha”L)

Nevertheless, he laughed off some customs, considering certain practices the Rema highly honored as “foolish customs”. He laughed, for example, at the custom of hopping while reciting the Kedusha, at “Kadosh, kadosh, Kadosh… “. The Rema, on the other hand, was very observant of every custom of the People of Israel.

The Rema and the MaHaRSha”L were devoted friends. However, their methods of study were very different, and that the latter opposed the scholarly direction of Rabbi Sholom Shachna, while the Rema – as a son-in-law and pupil of his – followed and reinforced his father-in-law's way of study. They were true friends, although the two had several sharp polemic discussions.

When it came to analyzing, critiquing, and questioning one of Rema's interpretations, rules, or ideas, the MaHaRSha”L did not hold back from speaking very piercingly. The friendship between them did not restrain this man of truth and uncompromising principle, Rabbi Shlomo Luria, from saying what he felt and thought (“love did not corrupt the propriety” – as Horodetsky expressed it).

The MaHaRSha”L as a halachic Decisor

Rabbi Shlomo Luria differed from the Rema in every respect, especially in his sharpness and his critical approach to everything created in rabbinic literature after the Talmud. He showed no favoritism, not even toward the greatest authorities, because he found minor flaws in all of them. Therefore, their work must be analyzed. If the MaHaRI”K expresses something about a dispute between Rashi and Rabbeinu Tam about tefillin, “Who will place my head between the two tall mountains…”, then MaHaRSha”L says to that, “For certainly Jephthah in his generation is like Samuel in his generation.” (Yam Shel Shlomo, Bava Kama, chapter 2, section 5).

[Page 67]

|

|

(The photograph was taken a few years before the Second World War by A. Kacyzne) |

[Page 68]

The MaHaRSha”L refuted and criticized with firm conviction if he found an inaccuracy with someone, because there was no genuine authority above the masters of the Talmud for him concerning Jewish law. It was not without justification that one of the famous rabbis said about him: “And we find that the RaSha”l [i.e. the MaHaRSHa”L] even disagrees with the great Rishonim, for his heart is like the heart of a lion.”

It takes someone with a lion's heart to say about Rashba, “It is a tenuous claim, a rumor that flutters in the air; therefore, it is rejected.” (Responsa section 10); or to say about the author of the Tur, “Everyone thinks that his reasoning is conclusive, almost as though it were a law given to Moses at Sinai. But this is not so. What does it matter that he agreed with his father? We do not necessarily agree with him in matters of halacha. And so it is in several places in the laws of the forbidden and the permissible, where we do not follow his position. (Yam Shel Shlomo, Chulin, chapter 1, 32); or he ventured to say, “And he made a great error.” (Yam Shel Shlomo, Yevamot chapter 8, 38)

He dared to write about the “Mordechai”, Do not rely on the ‘Mordechai,’ for you will find conflicting opinions there – one saying this and another saying that – and they are scattered throughout. (Yam Shel Shlomo, Bava Kama, chapter 9, section 30). He once said about the Ramban: “And my master, the great Ramban, permitted it to me.” (Yam Shel Shlomo, Chulin 8, 64). About others like the Ra”n, Beis Yosef, and others, he wrote even sharper and more biting words, having already expressed himself in this manner about the other rabbis of his time, many of whom he dismissed “as the dust of the earth.” He considered some of them as babblers, “conceited” and whatnot. (See Yam Shel Shlomo, Chulin, section 25; Responsa of the RaSha”L 14; ibid. 75; introduction to Yam Shel Shlomo, Chulin, and others.)

The MaHaRSha”L related about himself: “I have not shown favoritism to any one of them”; “I do not take into account the axiom of the generation, that what is written is an old document, “in ancient lettering”, cannot be revised, “One does not raise objections about him”; With complete belief and loyalty, I have discovered that they made many errors regarding Talmud…” Therefore, I have set my face like flint to declare about them: I have set myself above all of them; indeed, they will be judged as any man. Therefore, I will not place my trust in any one of the authors more than in his colleague, even though there is a significant difference in their stature to one who has become accustomed to studying them intensely. In any case, it is the Talmud that decides, with clear proofs; let them bring their evidence and cry out…” It was his firm intention that, since Ravina and Rav Ashi, it is not the tradition to decide in favor of one or another of the Rishonim, but instead to rely on that on which he based his words: the Babylonian Talmud or the Jerusalem Talmud. And if he found an incorrect interpretation, an unsubstantiated decision, a not-well-founded interpretation, he did not consider the personality behind the words but openly declared his oppositional stance. “Even though it emanated from his mouth, and he is a great person, we do not take it into account,” was his slogan.

For him, the highest authority was the Talmud, the greatest creation of the Jews. He spoke about the creation of the Talmud in spiritual terms, in flowery language, using words the Tanna Rabbi Akiva used to describe the magnificence of the Song of Songs: “The entire world is not worthy of me.” Furthermore, the most essential part of the Talmudic corpus is the Gemara, as an expansion of the Mishnah. He praises the Talmud with the strongest words. If he says a word that someone can interpret as against the Talmud, he responds and defends himself, that he is, Heaven forbid, no opponent of Talmud apologetics: “And I do not disagree with the Talmud, for it has no practical halachic consequence – neither for liability nor for exemption.” Talmudic law is sacred to him, both when it makes things more complicated and when it makes things easier, and when the Sages of the Talmud did not issue a decree, he maintains that today's rabbis must certainly not issue decrees. Only in practical halacha, especially in laws of kosher and treif which were not definitively resolved in the Talmud, one must use the erudition and opinion of the learned ones to clarify the law. But where the law is clear in the Talmud, it is the highest authority.

Every word of the Gemara, he stated, endures every doubt, and no one can change any part of the spoken meanings in the Talmud, either to make laws more strict or more lenient. He opposed making laws more stringent than those in the Gemara.

And remarkably, he allowed himself to write, as we have seen, very clearly, that he could not agree with Rambam, Rashba, Tur, Ramban, Ran, Rabbeinu Bachya, the Mordechai, the Beit Yosef, Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi, and many others. But he never criticized Rabbeinu Tam. He spoke out sternly against the book “Migdal Oz”, a commentary on Rambam and the responsa of Binyamin Zeev, distinguished works in

[Page 69]

rabbinic literature. The MaHaRSha”L stated his opinion that the books contained “strange words that are confusing,” that there were wild, unfounded thoughts, and that it would be much better if the author had remained completely silent. He published his ruling that one must absolutely not rely on them. This was a strong verdict, a strong revision. He wrote about the books with Gallic irony and sarcasm.

Now we come to a notable event in MaHaRSha”L's life path and mode of thought. Himself a lover of grammar, he often reprimanded Rema for his negligence in grammar. He was passionate in his battle for linguistic purity and straightforward style. He scolded the rabbis and commentators who disparaged the language. On the other hand, he was its apologist, idealizer, exalter, and refiner. Furthermore, when he came to the person of Avraham Ibn Ezra (4752 – 4827, 1092 - 1167) – the famous grammarian, philosopher, scholar, philologist, and word-artist – he was not merely unmoved by him. Still, he was outright opposed to studying Ibn Ezra's commentary, which often violated the meaning of the Sages of the Talmud.

In his introduction to “Yam Shel Shlomo” he spoke with bitterness against the Rambam (4905 – 5015 1185 - 1255)[4], who had written a letter to his son, Rabbi Avraham, drawing him toward the study of the books of Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra, whom the MaHaRSha”L considered not to be a Talmudist. He wrote about Ibn Ezra: “And most of his constructs and commentaries are based on physical properties and natural causes, and on accepting external factors and leniencies in several areas outside the words of the sages of the Torah and Talmud. What is from the Torah he declared to be rabbinic, and what is rabbinic he elevated into words of Torah… And his honor remains in its place, for he was a great sage, and one does not answer a lion. Yet we do not follow his explanations – whether in matters of prohibition and permission, liability and exemption – for he wrote contrary to halacha several times, even against innumerable sages of the Mishnah and the sages of the Talmud. In truth, I have heard that he had decreed and publicly proclaimed that he does not wish to show favor, but rather to explain in accordance with wherever his intellect lands, were it not for the received tradition – as he hints in several places in his commentary on the Torah: ‘Were it not for the tradition, I would have said…’

The MaHaRSha”L also criticized the Rambam here and mentioned “An error with the French sages…”. He said with satisfaction: “And indeed, the Rambam has already been sharply criticized, for one of the great men of his generation – the pious and pure Raava”d – rose to challenge him and took issue with him in numerous places, beyond measure. Moreover, regarding the Rambam's statement in his book that [one who holds this belief] is a heretic, the Raava”d wrote that many sages greater and more eminent than he had this very view.”

The MaHaRSha”L's way of learning was strictly analytical, pedantic, everything sifted through seven filters, as he himself explained: “I examined and investigated very well with seven investigations and seven examinations and probes after every source of the law, and I established the halacha through great effort and extensive breadth of sources.” (Introduction to Yam Shel Shlomo, Chulin). He did not hurry in study, immersing himself in a matter for a long time and working on it with all his senses. He was the “master of penetrating analysis.”

Indeed, he relates that in two years of studying the [tractate] Yevamot, he had completed half the tractate, and in the year he studied Ketuvot, he only completed two chapters.

He wrote even more painstakingly, but, in spite of this, he was the author of many holy books. Once he deliberated for a week until he found a source for his thought, and only then recorded it in a book… See his own words: “At times I sat for an entire week absorbed in contemplative thought until through my effort I found the root of the matter, and then I wrote it in a book,” where he tells us that he is also not rushed in carrying out his verdict about this or that work: “I did not leave behind any author in which I did not deliberate over before sealing the verdict.” (aforementioned introduction to Yam Shel Shlomo, Chulin).

The MaHaRSha”L composed many books. Later, I will provide a list of his works. The largest and deepest work of his books (which now lies on my desk) is the “Yam Shel Shlomo”, seven volumes on seven Talmudic tractates: Beitza, Gitin, Kedushin, Yevamot, Ketuvot, Bava Kama, Chulin.

As I mentioned, he lived in an era of great religious authority, yet he still merited the greatest recognition and popularity. His expertise in Talmud and halachic decisors was considered a phenomenon. However, he did not merit to remain the preeminent halachic authority. The Rema merited that. The latter rose to the highest authority as the halachic decisor for Ashkenazi Jewry. That

[Page 70]

demonstrates the veracity of an old truth, that the world does not reckon so much with the brilliant capabilities of a person, not even with the zeal and diligence of a person, but mainly on his personality and lifestyle.

It is the old echo, “The halacha is like the House of Hillel.” It is the law of the yeshiva of Hillel, not because they were sharper and better learned, but mainly because they were modest people; they conducted themselves with humility and listened to the opinions of others.

The Rema acquired his authority even though he lived and worked in the time of giant personalities with brilliant acuity, as did MaHaRShA”L, because the Rema was more farsighted, more sedate in his judgments. He possessed extraordinary perception and a marvelous memory, synthetically woven together with his personality as a symbol of the Torah Jew.

MaHaRShA”L's Relationship to Kabbalah and Philosophy

Even though our biographical sketch about the MaHaRShA”L takes up tens of pages, I do not intend to give a detailed critical analysis of his creations here. I only provide an outline and short chapters on the biographical-psychological character of one of the first Polish giants during that great Lublin epoch. I will also suggest, in a limited manner, a certain contradiction of the MaHaRShA”L's, which is characteristic of him, as for all the Gaonim of all times.

The MaHaRShA”L, with his innovative ideas which pertain to laying a new methodology for the study of Torah and Talmud, was the first “great one” in the Poland of that epoch, who demonstrates such a strong will and knowledge concerning Hebrew, still remaining true to the fractured state of the surrounding world with its “ailments”. He demonstrates an open aversion to the Rambam, who carried himself with aristocratic tendencies, and instead showed his great respect for the rabbis of France, those most faithful to traditional Orthodox Judaism, and especially for Rashi (perhaps because he considered himself a descendant of Rashi!).

In the MaHaRShA”L's time, that is, in the 16th century, the Kabbalah of the “Zohar” and Ar”i (Rabbi Yitzchak Luria Ashkenazi of the Land of Israel, 5294–5332; 1534–1572) had begun to infiltrate Poland. Of course, there could be no talk about the broader folk masses learning Kabbalah. However, there were already individuals who devoted themselves to studying Kabbalah, immersing themselves in the teachings of Jewish mysticism. The MaHaRShA”L and the Rema devoted time to studying Kabbalah, but their views of the Kabbalistic teachings were very different.

One finds Kabbalistic influence and Kabbalistic tendencies with the MaHaRShA”L as well, and he believed in them – as seen in his chidushim [novellae] and the revelations in “ruach hakodesh” [Divine inspiration], just as Rabbi Yosef Karo had a “Maggid” from Heaven. He was branded, though, as a strong opponent of Kabbalah, particularly when it comes to relying on it in halacha. For him, Talmud and rabbinic decisors stood much higher than the Zohar, and of course the mystical teachings of Kabbalah of the Ar”i and other Kabbalists.

He wrote the following in his responsa (section 98):

”Those who asked me whether the proper custom is to don tefillin while sitting or standing… they know, my dear one, new individuals have arisen of late, new people have come who desire to be among the Kabbalist sect… They have not even come into the light of the Zohar, in order to understand what it means. Rather, they have only found it in the books of RaShB”I… those who were our holy elders up until today, world-class Gaonim, have conducted themselves just as the Talmud directs. Even when Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai comes to us shouting to change a custom from antiquity, we do not obey him. The fact is that most of his statements in the Talmud are not in accordance with the law as stated by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai.” He concludes that immersing oneself in the secrets of Torah and Kabbalah, we see that one cannot abandon one's own good sense in the mystical teachings, and that the best thing is to immerse oneself in Talmud and rabbinic decisors. As for tefillin, they should be donned while standing.

[Page 71]

However, this shows that Kabbalah had such an effect on him that he hated rationalism and philosophy in general, and he expressed himself about them with the sharpest words, speaking with biting sarcasm against our great ones who had indeed occupied themselves with philosophy.

And it is important to cite here one of his responsa to the Rema, in which he reminded him of Aristotle:

“… He has surrounded me with bundles of clever sayings –

yet most of them are externalities,

idle tales of many kinds,

and the harm they cause is grave.

The Torah girds itself in sackcloth and mourns…

and you turn, at every corner,

to the wisdom of the uncircumcised Aristotle…

Woe to me that my eyes have seen this,

and all the more so that my ears have heard it –

that the sharpness and the spice [you prize]

are drawn from the words of the impure one,

and that such things should be, in the mouths of the sages of Israel,

like a cloud of fragrance for the holy Torah.

May the Merciful One save us from so great a sin…

To be sure, I too have a hand in their wisdom, as you do –

but I keep my distance from them, wandering far away…

And you have no heresy as destructive as their so–called wisdom….”

As one can see, the MaHaRShA”L was an extreme opponent of both Kabbalah and of philosophic rationalism. He exemplified the traditional rabbinic type – the symbol of a Rav and Rosh Yeshiva who studies Torah according to the Talmudic-scholastic order of study, on the wings of the spirit of the rabbis and sages of France. He is the type of Gaon, like the Vilna Gaon (the 'GR”A of blessed memory, 5480–5558; 1720–1797), a sharply polemical rabbinic Talmudist who, in his rigorous Talmudic studies, only used his new method for bringing clarity into the places that had long been unclear and dark. He fought against the fruitless casuistry and useless pilpul, wanting to bring in his new method of study and to understand the Talmud is a more planned-out and systematic way; and at the same time he spoke out and sharply fought both the rationalists who believed that they could, with their logic, understand all the secrets of the Torah, and the Kabbalists who wanted to issue halachic decisions through Kabbalah.

Nevertheless, the hatred towards him from the side of the Kabbalists was unjustified, almost gratuitous. Even with respect to the Kabbalists, he had to fight hard for honor and admiration, and one of the important Kabbalists reproved the MaHaRShA”L with pronounced sharpness, maintaining: “His lips utter presumptuous arrogance in these discourses, spoken with pride – and all this I myself witnessed at the time. The very substance of his words was nothing but empty vapor, for they violated the discipline of analytic study and broke the bounds of moral propriety. It is unfitting for any wise or discerning person to respond to them or to pay them any heed.”

Certainly, the MaHaRShA”L did not agree with the creators and interpreters of the mystical teachings who wanted it to be placed above the revealed Torah. As many leading rabbinical personalities believed, he, too, considered the Gemara as the primary point, and things not mentioned in the Talmud, even if they had indeed been mentioned in the books on Kabbalah, are not law.

Therefore, we understand his enthusiasm for the sages of France, believing strongly in the classic folk saying, “For out of Tzarfat [France] shall go forth Torah, and the word of G-d from Ashkenaz”, a paraphrase of “For out of Zion shall go forth the Torah, and the word of G-d from Jerusalem.” [Isaiah 2:3].

The Sephardic Jews were not overly enthusiastic about the sages of Ashkenaz, maintaining that their own creations in every area stood much higher, and one of the Sephardim openly declared: “The words of the authors are always correct if they are from the Sephardim, especially the words of the Rambam, which always have all fine characteristics, both internally and externally. And all the sages of France are like a husk of garlic in comparison to him…” (see Yam Shel Shlomo, introduction to Tractate Chulin).

The Rambam himself once spoke dismissively about the sages of France. The MaHaRShA”L, on the other hand, had a very elevated opinion of the Rambam, and wrote about him with these words: “Anyone who looks into the words of the Rambam will see how great a sage he was,” “And he was the father of all the physicians and naturalists,” and so on. He was enthusiastic about the Rambam's order in his Mishneh Torah and wrote: “He constructed a work that is finer than anything that preceded it, in respect that it is orderly in its laws and halachic decisions…” Nevertheless, he pointed out his major deficiencies and errors. He believed one must criticize the Rambam, and he did so in his style, with harsh words. He was happy about the attacks on the Rambam by the Ra”avad, whom he called “pious and pure…”.

He showed greater enthusiasm for Rashi and Rabbeinu Tam, calling the former “pillar of the world” and the latter “the holy mouth.” He used the most splendid words about Rashi, “From whose waters we drink…”

[Page 72]

He regarded the work of the French sages on a very high level, as the creators of Tosafot, who made the Talmud accessible. Nevertheless, that did not hold him back from stating his words even on the Baalei Tosafot [Tosafists] if he found contradictions in them, once bringing out words and comments in one place for Rabbeinu Tam and in another place for R”I, RIB”A and others of Rashi's grandchildren. (See the notable, historically interesting introduction to Yam Shel Shlomo, Tractate Chulin.)

He pointed out a remarkable phenomenon regarding their inconsistencies:

“It was not enough that their own circle did not settle the matter for us; you have rekindled from them the very confusion they left behind. And the Torah has not become merely two Torahs, but six hundred and thirteen Torahs, from the sheer multitude of disagreements. Each one builds an altar for himself, as though he held the scales of righteousness in his hand, weighing with the sacred measure and tipping the balance toward his own side.”

If he, the Gaon Rabbi Shlomo Luria, had applied the same scrutiny to his own words, he would not have done many things and would not have spoken with such certainty.

|

|

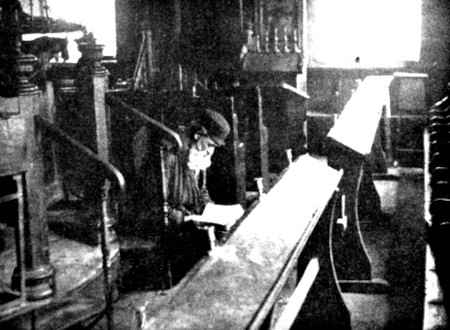

| The Yeshiva Lad (Photograph taken in the Yeshivat Chachmei Lublin) |

The MaHaRShA”L's Books and His Students

The MaHaRShA”L composed many important books, chidushim [novellae or novel interpretations], halachic decisions, and glosses and emendations. As a great expert in Tanach and grammar. He easily mastered the Hebrew language and the Talmudic manner and style, and thus he wrote a great deal. Here, I will give a short list, as the “Toldot Haposkim” {History of Rabbinic Decisors} enumerates his works.

[Page 73]

Shulchan Aruch. Who knows if any of the manuscripts remain in Europe after the Nazi inferno?

The MaHaRShA”L's responsa reflect very clearly the spirit of that epoch, and the methodology of Talmud study during the yeshivas of Poland of that time, and so on.

One also becomes acquainted with the rabbinic systems of the time, as well as with the powerful figures who, in a certain sense, dominated Jewish religious life.

He expresses himself very sharply against the students who do not understand anything but still follow after their teachers, however poor they may be, damaging their lives, ruling and dominating the Jewish environment wherever it goes. They are forced into a futile and difficult path of wandering. In one place, he writes to the Rema – that very temperate and careful student of Rabi Sholom Shachna – “Regrettably, from the rebellion of my students who rebel and sin against me… they are the ones who lead me beyond my limits, and are weakening my body… A craftsman who cannot withstand the blow of the pestle is unfit to remain in his post. So, either I am no longer able to continue in my position, or may God grant me life and the strength to save my own soul and the souls of the worthy students from their hands – even as I dwell in the land of my enemies (Poland)…”

As a genius who fully mastered the Hebrew language, he developed his own particular forms of expression in presenting the social situation of his time. He was almost the first spokesman and advocate for wholeness in Jewish society, so that the “tax” controller should not be allowed to dominate Jewish life.

Without violating the ideological framework of rabbinic rule and the position of the rabbinate among Jewry, he came out strongly against the rabbis who obtained positions for money. (As well, his friend, the Rema, also came out strongly at that time against that tendency of a money-dominated system.) He cautioned about the dangers this could bring to the Jewish way of life.

In some matters, he was a rigorous interpreter of the laws, for example, with regard to modesty and separation regarding mixed dancing. For him, that was prohibited with the strongest stringencies, and he said about that: “My heart burns like an oven over the nation of G-d… who play various musical instruments…” In his Responsa, he says, “The arrogant ones and the wealthy ones, who walk with an upright stature, with raised necks, and are careful about going around bareheaded, but not for reasons of piety…” (Responsa, section 72). Notably, the MaHaRShA”L – who is in so many traditions and customs very conservative, favoring the most rigorous application of the laws – is very lenient regarding going bareheaded and laughs at the rabbis of Ashkenaz who so strongly forbid the uncovering of the head, and reproves the paradoxical leadership of the rabbis, especially regarding the following fact: “Every person… as long as he is wealthy and powerful, one does not check him out, and one grants him honor. On the other hand, if someone who has no money eats and drinks in a kosher manner, but he sits with his head uncovered, they grab him as if he has excluded himself from the community…” (ibid. in the third Lemberg edition, published by his grandchildren, Yosef Cohen Tsedek and Zalman Bokhard, with the style slightly modified.)

This is not the place to reprint that very interesting responsum, in which the MaHaRShA”L demonstrates his full brilliance as a genius and a personality who dares to come out unflinchingly, even when he is against the great halachic decisors of Ashkenazic and Sefardic Jewry, as is the case with the issue of the ban on bareheadedness. In “Toldot Haposkim” [History of halachic Decisors], the remarkable responsum is reprinted in its entirety as in the first edition of the Responsa book. The outcome is that because of a “standard of piety beyond the letter of the law” [midat chasidut] one must be careful to wear a hat on the head not only out in public, but even in privacy of one's home (and it is not for naught that they said that everything that is forbidden because of an appearance of impropriety [marit ayin] is even forbidden in absolute privacy), and of course during study, prayer and other specific religious occasions.

“Toldot Haposkim” tells about many of the great personalities who eased off that prohibition, including the GR”A, who expressed it this way: “There is no prohibition at all on having a bare head, other than before the great ones and during the time of prayer… and for the rest of the day, for the holy ones who stand before G-d constantly.”

Many rabbinical authorities forbade bareheadedness. The Shela ha-Kadosh was stricter and said that even children

[Page 74]

must cover their heads. He directed that one must keep the head covered even while sleeping. Also, in “Shulchan Aruch HaRav” (section 2, subsection 7; section 91, subsection 2), Rabbi Shneur Zalman firmly holds to the prohibition of not covering the head. Until this day, especially in the Hasidic environment, it is a crime and a “desecration of the Divine Name” to go without the head covered.

The question is still an actual issue today and remains of interest. The famous bibliographer and cultural researcher Yitzchak Rivkind has recently published a large, comprehensive volume titled “Responsum of Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh Modena on Bareheadedness”, New York, 5706 [1946], (a printed extract from a book in honor of Levi Ginzburg), which is primarily a commentary on the well-known yet newly-discovered responsa of Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh Modena, in which he permits bareheadedness. The question of bareheadedness was a particularly personal one for the Italian philosopher and Talmudist, as he had studied at universities and, on hot days, had also gone out on the street without a head covering, which the rabbis condemned.

In the responsum that Rivkind published according to a manuscript in the British Museum, Modena brought evidence and sources for his verdict about bareheadedness, among them also from the MaHaRShA”L (ibid. pp. 20-21). Indeed, let us allow ourselves to cite a few lines from that responsa from paragraph 72: “Years after I wrote the aforementioned, a responsum from MaHarShA”L Luria of blessed memory, the author of ‘Chochmat Shlomo’ and ‘Yam Shlomo’, a very great, influential man within all the people of Poland and Ashkenaz came to my hands. See and be amazed that even though the Ashkenazim are very stringent on such matters as is known, he is permissive… of bareheadedness, and certainly to go and stand by the reasons that I have written. I do not know what the hypocrites and ascetics would respond.” Because of excessive subjectivity, Modena did not closely examine the measured, contained words of the MaHaRShA”L, nevertheless, he dealt with them quite nicely. The well-known halachic decisions of Rabbi Yisroel Iserlin (passed away in 5220 - 1460) in “Terumat Hadeshen”, section 197, and Rabbi Yisroel Bruna (his Responsa, Stettin, section 34) state that “it is absolutely prohibited for a Jew to go bareheaded like the non-Jews,” already discussed regarding a sacred act. However, I am not writing about bareheadedness. At this moment, we are only interested in the MaHaRShA”L's opinion. (See also Moshe Liter, “Zuto Shalom” 5692 [1932], pp. 87-88 regarding bareheadedness and head covering; covering the head leads to the awe of Heaven, as it says in the Talmud, Shabbat 156b, and, as was the case in antiquity, it came to be considered evidence that a person is not a slave. By wearing a hat, one manifests the freedom and redemption from Egypt. Also see “Magen Avraham” Orach Chaim, section 8, subsection 3; “Beit Yosef”, Orach Chaim, section 91. He concludes it is an ethical custom, a sign of holiness in the wearing of a hat on the head. Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsh firmly held to that…)

The MaHaRShA”L had many students. I will list a few of them here:

Rabbi Mordechai Yoffe held rabbinic offices in various cities and communities. For a time, he was a rabbi in Lublin, and, as the Serotzker [Serocker] Rov, Rabbi Yosef Levenstein writes, he was there in the year 5348 [1588]. Later in life, he became a rabbi in Posen and died there. See “Sefer Zikaron” [Book of Memory] by MaHaRI”L Grauart about the great ones of Poland. These words were etched upon his gravestone:

This is the grave marker of the Gaon:

The head of the rabbinical court, our teacher Rabbi Mordechai Yoffe of blessed memory,

Adar 3, 5372 [1612]

14 – 15. The brothers, the Gaonim Rabbi Yaakov and Rabbi Helman, the sons of Rabbi Chaim Virmiz. Their elder brother, Reb Betzalel, remained at home studying with their father. When they came home from Lublin and recounted [the teachings and] stories [they had heard], the older brother was very envious of them and regretted that he had not gone there. The father blessed him with four luminaries, which were to light the world with their Torah study, and so it was. The blessing was fulfilled. He had four sons: The elder, Rabbi Chaim, became rabbi of Friedberg, author of “Sefer Chaim”, “Ezrat Hatiyul”, “Sefer Mayim Chaim”, and critical remarks on the book “Torat Chatat” by the Rema. The second son, Rabbi Sinai, was a Yeshiva Head in Prague, then Rov in Nikelshpurg [Nikolsburg] and all of Moravia. The third son, Rabbi Shimshon, was a rabbi in Kremenets, and the fourth, Rabbi Yehuda Löw, the Maharal of Prague, was the most famous and the MaHaRShA”L praised him strongly. (Family tree of Rabbi Meir Perelish, a relative of the Maharal).

The MaHaRShA”L, as we see in the introduction to “Chochmat Shlomo”, (printed for the first time in Krakow

[Page 76]

|

|

| The bima in the MaHaRShA”L Shul (According to the drawing by K. R. Henker) |

[Page 77]

In the year 5347 [1587], had two sons: Rabbi Wolf and Rabbi Yechiel. Nisenbaum, in his monograph of Lublin, remarked that their lives are unknown to us. Only the gravestone of Rabbi Yechiel is known:

The gravestone of Rabbi Yechiel, son of our teacher, Rabbi Shlomo Luria

Here is buried

An upright and faithful man

The sublime, distinguished scholar, the son of the distinguished scholar and Gaon Shlomo Luria

For these… We shed tears and weep,

In the year 5354 [1594]

His soul ascended heavenward to the supernal altar to ascend as sacred ash.[7]

May his soul be bound in the bonds of eternal life.

The MaHaRShA”L's son-in-law, Rabbi Shimon Wolf Auerbach, was his successor in the Lublin Yeshiva, while the MaHaRa”M of Lublin was the one who bore the mantle of leadership in practice. That Gaon Rabbi Shimon Wolf was one of the most well-known personalities, and occupied rabbinic chairs in Turbin, Lumbala [Luboml], Lublin (5339 – 5345 [1579 – 1588]), Premisla [Przemyśl], Posen, Vienna, and Prague, where he died on 17 Cheshvan, 5392 [November 1631]. His gravestone etching begins with:

”A wolf has been seized in the morning of Wednesday…on which the luminaries were diminished,” and is adorned with the most powerful laments, taking up one entire page in “The Annals of the Jews of Lublin”. His son-in-law, Rabbi Kasriel Heilperin, is the grandfather of the author of the famous book “Seder Hadorot” [Order of the Generations] (died on 5 Tammuz, 5403 [June 1643]).

a day of curse and bitterness,

At that time in Lublin, there also lived the Rabbi Shlomo Rofeh [the physician] Luria, a Gaon of renown, author of a treatise “Luach Hachaim” [The Calendar of Life]. Apparently, he was a cousin of the MaHaRShA”L, and the latter related to him with great respect in one of his responses. Rabbi Shlomo Rofeh had a son, Rabbi Yechiel, who was the co-parent-in-law of the Tosafos Yomtov. His daughter Esther married Rabbi Avraham, the son of Rabbi Yomtov Lipman (5339 - 1579; died in Krakow in 5414 - 1654). The wedding took place in Lublin, and Rabbi Avraham became a resident of Lublin. (See “Megilat Eicha” by the Tosafos Yomtov, which mentions that on 3 Tammuz, 5395 [June 1635], he, his wife, and youngest son, the intelligent lad Avraham… to the wedding, on the day of the rejoicing of his heart, in the holy community of Lublin… See also Tosafos Yomtov, Sukka 1:1)

The MaHaRShA”L also had a son-in-law, Rabbi Eliezer Viner, who died in Vienna on Rosh Chodesh Av. He was the father of Rabbi Moshe Leizers of Brisk, publisher of the responsa of the Rema. The MaHaRShA”L's well-known wife was Lipke. Much was written about her, too.

As stated, the MaHaRShA”L was a great grammarian, knowledgeable in Hebrew, and a good stylist. He was also, according to the contemporary milieu, a historian, an exacting chronicler, and knowledgeable in genealogy. He demonstrated that in his masterful responsum 29, in which he outlined the order, beginning from the Gaonic era, up to the Tosafists and the great halachic decisors. He also composed an exacting genealogical record of the famous Luria family.

His great-grandchildren – following after their great ancestor – produced works in the area of Jewish historiography and chronology. Thus, Rabbi Yechiel HaGadol of Minsk, son of Rabbi Shlomo Shklover (previously the Levertover Rov), author of the well-known “Seder Hadorot”, a monumental work on the generations of the great scholars of Israel, as well as the more recent “Shem VeShe'erit” by Yosef Kohen Tzedik and many others. For the MaHaRShA”L, historiography was one of the fundamentals in understanding the Tanaim [sages of the Mishnaic era] and Amoraim [sages of the era of the Gemara], and those who followed, the protectors of their statutes in the entire Jewish Diaspora.

We mentioned earlier that he was a liturgical poet and could weave verses in the style of the time. Thus, he expressed his enthusiasm for the Talmud in a beautiful poem as an introduction to “Yam Shel Shlomo” Bava Kama.

The grandchildren who published it prefaced it with the superscription: “A Song of Songs which is Shlomo's – by the Gaon, author of Yam Shel Shlomo, ranging from east to west”:

Brich Rachmana

Blessed is the Merciful One,

Who grants wisdom to the wise with gracious favor.

From hiddenness, from the inner exalted rung conceived in understanding,

The gates of the wellspring, from the forty–nine gates of discernment,

Will open before them when kindness and grace are found.

A mighty dominion will they merit, more precious than pearl,

For kings–He who is their shield and protector.

A little path and much toil with but little sleep,

The very being of the Talmud–Abaye and Rava, Rav Ashi and Ravina–

Blessed is the Merciful One

Who grants wisdom to the wise with gracious favor,

From hiddenness, from the inward rung to the outer.

[Page 78]

Gates of light, mysteries of wonders;

The hearts of kings are in the hand of God.

There the Ark of the first ones lies hidden,

The tablets engraved–or the tablets of freedom–precious within.

Moses gave the Torah to the children,

And Rava stands ready in it–strong and steadfast in faith…

The introductions to the books of “Yam Shel Shlomo” are written in a bold language, in a style that is truly “refined sevenfold”. Very few rabbis, halachic decisors, or Torah greats can compare to the MaHaRShA”L in matters of language. Who had such fine expression as he did when trying to defend the Raava”d (the critic of Rambam)? The MaHaRSHA”L states, regarding the criticism of “Migdal Oz”: “He writes his words like one who lashes and distorts, and his scant, flavorless phrasing – without taste or scent – is nothing but a waste of ink…”

[Page 79]

The MaHaRShA”L Shul in Lublin

Far below the castle on the hill stands the old, hemmed–in, imposing Lublin shul named after the famed halachic decisor, commentator, and Yeshiva Head, the “MaHaRShA”L Shul”. The shul was built to be massive, right at the very beginning of the Lublin Old Town, which was cut out of the mountain. From that depth – which gave the impression of a remnant of the dark Middle Ages and of the crowding of the ghetto in Lublin, for the last three or four hundred years, cries have called up to G-d “from the depths I call to you, G-d” [Psalm 130-1]. From those narrow little streets around the castle hill and the Bystrzyca River, Torah was studied and disseminated. There, the greatest rabbis of Poland used to come to convene; there, the international fairs took place; there, the deliberations of the famed Council of the Four Lands convened.

The shul was built in 1567, by virtue of the privilege of King Zygmunt August, on a place that belonged to the Jewish doctor Yitzchak Maj.

Professor Balaban writes about the history of Dr. Maj:

“On the 11th of October 1557, the Jewish physician Dr. Yitzchak Maj bought from that same Starosta (Andrzej Teczynski – N. Sh.) a damp area of land near the large river, at the foot of the castle-hill, with the right to build a house there. The drying out of the land went on for several years, so the doctor had to begin paying the annual taxes ten years after the purchase. On that piece of land, the Jewish community constructed a yeshiva and a shul, for which they had received a special privilege from the King on 23 August 1567.

“The shul that was built on the site was a massive building, large and fine, and given the name of the first and famous Yeshiva Head of Lublin, Rabbi Shlomo Luria – the “MaHaRShA”L Shul.”

Years later, another shul was built onto that shul. It was a smaller one, named after the MaHaRa”M of Lublin (Rabbi Mayer son of Rabbi Gedalya of Lublin – “MaHaRa'M Shul”). The shul was rebuilt after a fire in 1656, and again two hundred years later in 1856, and was renovated only after the First World War. The MaHaRShA”L Shul was the largest in Lublin. It had a more imposing appearance than all the Beis Midrashes, kloizes, and Hasidic courts in old-new Lublin.

Lublin, the great Jewish center, which was for a long time the seat of the Council of the Four Lands and of the largest yeshiva in those four lands, was, as we have mentioned earlier, well-founded economically due to the large fairs that took place there. That good situation is well reflected in the shul: as R. Vishnitser relates, the shul was “a large building that could accommodate, they say, several thousand people.”

The writer of these lines is well acquainted with the MaHaRShA”L Shul. He “visited” the shul almost every festival (because he worshipped at the Beis Midrash of the Eigers at Szeroka Street number 40). I was told that more than five thousand Jews worshipped in the MaHaRShA”L Shul, and about two thousand worshipped in the MaHaRa”M Shul. The city's rabbi would deliver his Kol Nidre sermon in the MaHaRShA”L Shul on Yom Kippur.

[Page 80]

As a child, I heard one such sermon by the Lubliner Rov, Rabbi Eliyahu Klatskin (5612 – 5693 in Jerusalem [1862-1933]), one of the great halachic decisors in our era, author of the halacha books “Imrei Shefer”, “Even HaRishon”, “Even Pina”, “Dvarim Achadim”, and others.

Also well etched in my mind are the Musaf services led by Reb Moishel Ajzenberg, a Lublin Councilman, well-known Aguda leader, and one of its officials, one of the closest coworkers of the Gaon Rabbi Mayer Shapira (died 7 Cheshvan 5694 [1933]), the last rabbi of Lublin and the founder of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin.

Reb Moishel was the son-in-law of a wealthy Jew from Krasnik, Reb Dovid Kohen, a brother-in-law of the Radziner rebbe. Himself a wealthy Jew, he still delivered a class on a page of Talmud every evening in the “Leifers' Shul” on Lubartowska (Levertover Gasse).

He was also a “kitva raba” [distinguished writer], as we used to call the scholars who could make very good use of the pen.

|

|

| Houses of the old Jewish style in the poor Jewish quarter of Lublin |

In his letter of the eve of the Sabbath of the [Torah portion of] Shmini, 5689 [1929], Lublin, he wrote to me: “Although the doors of the holiest institution have not yet opened, scholars are already knocking upon them… I have set down these words as a sign in the hands of the lad N. Shemen (Boimel), that with God's help he will be accepted among the group of students of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin… My strong hope is that even the Prince of Torah – our leader, the rabbi and Gaon of Piotrków, may he live – will concur with me in this…”[8]

R. Vishnitser depicts the beautiful building very well. “In form it is square, with four supports, each made up of three columns. The four supports are joined by wedge–shaped arches, and above them rests a square superstructure, richly decorated with stucco ornamentation. Under that canopy is the bima, a platform that is fitted between the columns… The windows are in the rounded lunettes of the ornamental carving on all four sides of the shul.”

As one well-versed in synagogue architecture, he depicts all the details of the appearance and construction of the shul as one of the oldest in Poland:

”The structural scheme of the MaHaRShA”L Shul is in harmony with the liturgical concept of a central bima and vividly brings out its importance. In the scheme, the supporting

[Page 81]

posts in the four corners of the bima are set in such a way that the Torah reader stands with his face directly toward the holy ark. In the sculpted, vaulted area surrounding the bima – a kind of walk–through arcade – are the places of the worshippers. They face the bima from all sides, except for the small area on the eastern side, which is occupied by the holy ark.”

R. Vishnitser shows himself to be an expert in Jewish history, cultural research, education, and even somewhat in scholarly matters, and he tells us there: “The position of the bima in the shul called out strong disagreements in the Polish rabbinic literature of the time. In his commentary “Darchei Moshe” on the Tur Orach Chaim, the Rema maintains that the place of the bima must be in the center, although in the Rema Shul – of which his father had overseen the construction, it is not exactly in the center but a little to the west. In the MaHaRShA”L Shul, the central position is determined by the architectural type. Aside from its function of supporting the vaulting, the canopy, encircled by columns, also elevates the importance of the bima. The structure of that shul is, without doubt, influenced by the Rema's positioning of the bima in his shul. The Rema stood in a close scholarly relationship with MaHaRShA”L and was also connected to him as an in-law. That fact probably gave rise to the spread of that type of “tabernacle synagogue in Poland.” (See drawing on page 76.)

The shul collapsed in the year 5617 [1857]. As Nisenbaum relates in his “History of the Jews in Lublin” (page 12), this destroyed an important document of a Siddur, written on parchment, in which the “Megilat Ta'ch” [the annals of the Chmielnicki massacres], and the pogroms in Lublin were recorded.

The MaHaRShA”L and the City of Lublin

Anyone who wants to get acquainted with Lublin's heritage must simply take a look at the old Jewish cemetery, the locus of the ancestral lineage of Old Lublin. The gravestones bear witness to Lublin's greatness and distant past.

The writer of these lines has visited the old Jewish cemetery in Lublin more than once – a burial ground more than four hundred years old. Among the oldest stones are those of Yaakov Kopelman, which, according to Nisenbaum, Balaban, Ajzenstat, and others, is the stone of Rabbi Yaakov Polak (born in Posen in 5220 – 1460 and passed away in Lublin in 5301 – 1541).

In the pantheon of the old Jewish cemetery, one can catch sight of the gravestones of Rabbi Shlomo Luria–MaHaRShA”L, of Rabbi Sholom Shachna, and other Torah greats of Lublin. There can also be found the graves of the famed rabbis of the 19th century, such as the grave of Rabbi Ezriel HaLevi Horowitz – “Der Eizerner Kop” [The Iron Head – Yid.], known in rabbinic historiography as “Rosh Habarzel” [Iron Head – Heb.]. In the same row is the grave with the huge stone of the “Chozeh”, the Lublin Rabbi, Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak HaLevi Horowitz, who came to Lublin from Lancut, Galicia, spread the teachings of Hasidism throughout Poland, and brought a new restoration to Lublin after the slaughters of Ta”ch veTa”t [The Chmielnicki massacres]. He was like a holy pillar of fire for the Jewish alleyways that were darkened with troubles and brought a new stage into the history of Polish Jewry.

Here is what the historian M. Balaban wrote: “The publisher of the Lublin gravestone inscriptions, Mr. Nisenbaum, and another Lublin researcher, Mr. Shafer, intervened with the Lublin Jewish Community Council for them to do something to save that precious historical monument; but they did not find any understanding from the council representatives, and they had to give up their plan. Thus, the cemetery went to ruin, which is a great, inestimable shame for Jewish history, and for the remembrance of the greats who are resting there. It is an act of ingratitude and a lack of veneration.”

Balaban, may G-d avenge his blood, wrote those words in the time of the First World War, when the war had brought him to Lublin. During his time there, he collected materials, took pictures of the gravestones, and then published his work on Lublin, with no pretensions that it was a foundational work of the Jewish City of Lublin. He regarded it as simply making a historical stroll around the old graves and monuments of Lublin. It is now so important that we have this historical stroll through

[Page 80]