|

|

|

[Page 129]

[Page 130]

[Page 131]

|

|

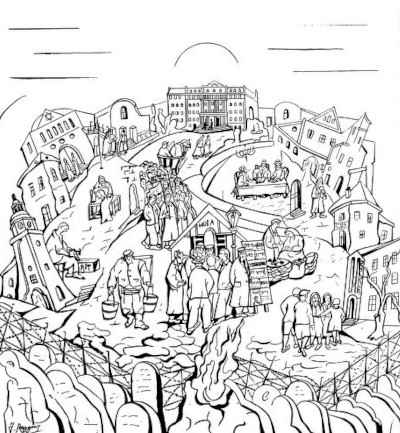

| Drawing by Razgour |

[Page 132]

[Page 133]

by Engineer Mordekhai Lerman

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

1914-1939 was a period of immense significance for events worldwide and for the development of Jewry in Poland, particularly in Jewish Lublin.

Whoever writes the history of Lublin cannot avoid referring to the events that contributed to the tumultuous history of Lublin Jewry.

If one speaks about a tumultuous history, these really were the years between both world wars. They marked the ascendency of our history although it was accompanied by constant struggles for existence that, alas, ended with a tremendous catastrophe.

New winds blew across the world, particularly across Europe at the beginning of the 20th Century. New winds warned the Tsarist tyranny of a stubborn fight and not only the Tsarists but also every national and social oppression. Eastern Europe, which suffered the most from the despotic rule of the Tsarist rulers, especially began to revolt, and among these Eastern European nations were also found we Jews.

And if any nation had suffered from the brutality and the tyranny of the ruling classes, it was principally the Jews.

The tendency toward assimilation among the Jewish population, which carried to West and East Europe, did not provide and also could not provide any solution to the Jewish question. The Jewish masses did not follow the movement because it was led by the bourgeoise who were remote from the masses and, even under the best conditions, could not provide suffering Jewry with radical help.

Years of innumerable pogroms and years of death for thousands of Jews did the opposite – it strengthened the national feeling and group resistance against the oppressors. Therefore, we found many Jews in the political freedom movement, including many of our Lublin Jews.

The tumultuous development of capitalism in Russia, which began in the 1890s and persisted, with pauses, until the First World War, fundamentally changed the appearance of the Jewish community. Class differentiation began. A Jewish proletariat arose, and with this began structured party life. A Jewish socialist movement arose. Conversely, a growing number of the halutzim [pioneers] went to Eretz Yisroel to build the old-new home for all of Jewry. At the same time, Orthodox religious Jewry remained a passive part of Jewry. And could only maintain the wish of next year in Jerusalem, waiting for the mystical moshiekh's [redeemer's] times.

However, the beginning of the 20th century did not bring any changes in the restrictions and limitations on Jewry. The Jews still could not buy land and, therefore, were excluded from farming from the start. The development of the proletariat was difficult, particularly in the large industries.

The merchants, retailers, and artisans attracted the majority of the Jewish population.

The years of the First World War and its start, which led to the triumph of the October

[Page 134]

Revolution, was supposed to radically change the political situation in the world. For Polish Jewry, things also changed politically; in many areas, the Polish bourgeoisie and landowners replaced Tsarist rule. The ruling classes of Poland between 1914 and 1939 very quickly forgot their 150 years of suffering national repression and did not treat the Jews any better than the Tsarist satraps.

However, the difference was that the new winds of freedom that began to blow across Europe did not avoid Poland and increased the feelings of social protest and national consciousness of national solidarity among the Jewish population.

The Zionist movement showed world Jewry a new road; the workers' unions in the Jewish neighborhood found help and greater understanding from some and lesser understanding from others in the non-Jewish neighborhood.

We also found Lublin and the glorious Lublin Jewry in this same situation.

The materials that we are publishing certainly do not reflect all branches of Jewish economic, political, communal, and cultural life. It is very difficult for us to immediately gather more material when everything that represents the great, Jewish Lublin is no longer here. However, we are sure of this, that the future researcher of the city in The Council of the Four Lands will find in this material an important source of help in illuminating the development and formation of the great Jewish community that inhabited the city of Lublin.

And it was large in number and in worth. Before the Second World War, the Lublin Jewish community was approximately 40 percent of the general number of residents, which had reached 120,000 souls. The well-known Lublin Jewish area was Jewish in the true sense of the word. It was large enough for one to stand at the beginning of Nowa Street and take a distant look at Lubartowska [Street] and you saw Jews and almost only Jews. The businesses were Jewish. The artisans, Jewish – the handworkers, Jewish – the workers, Jewish – the majority of the customers, Jewish – horse-drawn coaches, Jewish – stagecoaches, Jewish. We must also remember that Lublin was a center for the surrounding shtetlekh [towns], whose residents came here to buy their necessary goods.

The mobility was great. Jews went to Lubartowska Street. And from there, other streets, someone spread to Kowalska, someone to Cyrulicza, another to Rasza, another to Czatek, someone to Bonifraterska, and around the entire Jewish area. It would not be a paradox to say that even the air was Jewish.

Świętoduska and Nowa were the first streets to the suburbs that were inhabited by Poles, but Jews broke through the ghetto and, little by little, also settled in the Polish area. Thus, Jews also lived in the Krakower suburbs of Królewska, Piarska, and so on, and also in the suburbs of Zamd, Wolye, and Czechiw. Jews had large businesses, which were an object for Endeke [member of the Polish anti-Semitic nationalist party] picketing. The artisans even had their place in the Krakower suburb.

But if one is to speak about the true Jewish Lublin, it is the part that began near the Krakower well, in the center of which stood like an irony of fate, the former castle that was transformed into a prison, the Zamek.

If one wants to learn about the struggle for existence that was carried out by Lublin Jewry all during the years until the Shoah one needs to descend into the area of Jewish poverty that was always called untern shlos [under the castle], meaning the area around the

[Page 135]

Zamek. Here lived the Jewish porters, Jewish shoemakers, poor Jewish tailors, locksmiths, and so on. Here, too, was the center of Jewish instruction, the khederim [religious primary schools], which children from three years on attended. Here also lived the teachers of young boys who taught the Jewish children Khumash [Five Books of Torah] and Rashi using the old system of using small whips; here also stood the famous Marashal Synagogue, the Maharam's Synagogue, all of the tens of houses of study that most of the time served also as gathering places for all of the toiling masses who came for a “conversation” about all of their daily struggles.

Shabbos [Sabbath] in Lublin. It was Shabbos as was written in the Torah. Jews rested. Dressed in Shabbos clothing, Jews asked God for a week of good income. And here, it can be boldly said that if not for the observance of the religious law requiring rest, the Jews would also have searched for a livelihood on Shabbos and never known any rest. What was seen on Shabbos was also seen on all of the holidays.

On a holiday, Yom Kippur [Day of Atonement], it felt like the Day of Atonement in the Jewish area and the entire city. Almost all movements seemed to cease, and one could judge how far the influence of the Jewish population had on the general economic life of the entire city.

However, the assertion that all of Lublin Jewry was among the poorest part of the entire city population is false. They were also among the wealthiest class. True, not many had large factories and large workshops that employed tens of workers. A more significant number were among the middle class, but we can also include the artisans who employed up to five or, sometimes, more workers. So, this group of artisans did not live poorly because the competition in the Jewish neighborhood was weak. There were very few Polish artisans in Lublin, and each Pole had to, willingly or unwillingly, come to the Jews. However, this detail also changed in the last years before the Second World War. More Polish artisans appeared, which became a strong competition for the Jewish artisans.

Most of the Jewish population in Lublin were artisans; first, because Lublin was mainly not a factory center and, secondly, because Jews were not admitted to the few Lublin factories.

Lublin was a city of officialdom, a center, a large and rich enough one, in the agrarian sense, an administrative region where the military was stationed, and which was a large train junction. All of the commerce in Lublin was consequently carried out by the peasants who came to Lublin to sell their products and buy clothing, footwear, and so on with their money. This Polish officialdom, who lived well from their salaries, and the officers had only one concern: to amuse themselves and carry out anti-Semitic agitation. Therefore, the Polish workers and the train officials had to endure a difficult struggle.

A sizeable Jewish proletariat, which consisted mainly of tailors, employees, and so on, arose from this economic situation in the city. This class constantly carried on a struggle with their Jewish employers, who themselves were dependent on Jewish merchants and chiefly on their Polish clientele.

The frequent conflicts between the workers and the employers pushed the former to organize professional unions.

The Bund, which simultaneously also underwent a political struggle as a socialist party, was involved with organizing these professional unions, as well as Poalei Zion (Left) [Zionist Socialists]. There were professional unions of tailors, shoemakers, barbers, leather workers, bakers, and so on. There was also a union of sales employees.

The Bund, thanks to its professional unions, grew to be the strongest party in the Jewish neighborhood; it had a large number of council members on the city council and in the Jewish kehila [organized Jewish community]. The previously mentioned Poalei Zion (Left), which also had representatives on the city council and in the kehila,

[Page 136]

also had a smaller role in worker life than the Bund.

The tenacious organization of the workers also forced the Jewish employers to organize themselves in an artisans' union. The appropriate unions often intervened in conflicts between the employers and the workers.

In time, Jewish merchants themselves began to fabricate prepared garments from their goods and, for this purpose, employed artisans who had their own union, which had split off from the general artisans' union.

The merchants were proactive in organizing themselves; they formed a merchants' union to protect their commercial interests, as well as in the conflicts with the artisans who worked at home, who incidentally were very much exploited [by the merchants] and also by the [government], which imposed heavy taxes on them.

As for the taxes, they were actually a very heavy burden on all of Lublin Jewry. Auctions of Jewish possessions took place very often because of nonpayment of the taxes on time – the well-known Grabski[1] hearses – horse-drawn hearses.

The economic conditions simply impelled the Jews to organize themselves into professional unions. These unions not only became an institution that resolved conflicts between work and wages but also became a support force for the neediest members. One of the primary ways this support was expressed was through the provision of credit.

Therefore, Jewish banks were active with almost every union, which played a large role in the life of the entire population. Thus, we had an artisan's bank, a bank for artisans who worked at home, a merchant bank, and so on. Even the religious Jews had their own bank.

The Gmiles-khesed kases [interest-free loan funds], which provided loans without interest, also played a similar role.

In addition to the bank system and interest-free loan funds, a series of communal institutions were active in Lublin that had as their purpose to help the needy. We thus had a Bikor Kholim [society to visit the sick], a Hakhonsas Orkhim [society to provide hospitality to visitors], Hakhnoses Kale [society to help poor brides], Pat L'Orkhim [bread for guests], Linas haTzadek [society to visit the sick] and so on.

In the later years, the TOZ [Towarzystwo Ochrony Zdrowia Ludności żydowskiej – Society to Protect the Health of the Jews] developed, which had a great significance in protecting the health system of the Jewish population. In the last regard, many [Jews] brought about the creation of the Lublin Jewish Hospital.

Thus, was economic life shaped for Lublin Jewry.

And the political, communal, and cultural life?

If one speaks about the ebullient political, communal life of a Jewish community, there is no doubt this is about Jewish Lublin. There was not one party, one society, or one cultural organization that was not active in Lublin.

As we have already said, the strongest party was the Bund, which played a large role in Jewish life and in the general life of the entire city.

The Bund, which found a partner in the Polish Socialist Party (P.P.S.) for a period with which to fight for its political ideals, very quickly saw that in the Party there were Poles who could not bear working with Jews.

As an antithesis to the Bund, the Agudah [political arm of Orthodox Jewry] was a strong faction in Jewish life, as was all of religious Jewry. The influence of religious Jewish communities was significant, although it began to decline in the years leading up to 1939. The Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva was a source of pride for Lublin, especially among the religious, who regarded it as a central institution for Jewish Torah study and learning.

They [Agudah] always acted as a bloc with the merchants at the city council and when the B.B. (Bezpartini Bloc [non-partisan bloc]), the so-called Sanacie [Jozef Pilsudski's political movement] received its mandate, [they also joined] the government bloc.

[Page 137]

The Zionist movement played a significant role, encompassing all parties across the spectrum, from right to left. This included the General Zionists A and B, Et Livnot (Time to Build), Mizrachi (religious Zionists), Poalei Zion (a leftist group), Hashomer Hatzair (the Youth Guard – Social Zionists), Hashomer Halumi (National Guard), Hanoar HaTzioni (Zionist Youth), Brit Temelod (Betar), and the Revisionists (a non-religious Zionist group founded by Ze'ev Jabotinsky). Additionally, the Halutz (Pioneers) and the League for Working Israel were also active in the movement.

The Zionist movement as a whole began to penetrate Jewish life even more and even began to match the strong influence of the Bund.

The ceaseless pogroms, the constant anti-Semitic agitations, the constant attempts at taking the economic opportunities from the Jews, and the lack of prospects of the young, who could not enter the university or the factory, had the effect of strengthening the Zionist movement.

However, the Zionist parties also carried on a struggle for the local interests of the Jewish population. Therefore, we see them, the Zionists, at the Kehila and at the city council and the already mentioned Left Poalei-Zion as a Zionist party, which organized professional unions.

Jews also had their part in the illegal communist movement. Trials of Lublin Jewish young people took place very often for the sin of belonging to the illegal revolutionary movement. The constant trials, which mostly came about thanks to provocateurs, did not in any way weaken the activity of the illegal communist movement, which also had a certain influence on the professional movement. During the last years, before the war, the communist movement grew, mainly among the young people in schools.

The same that is said about political life must also be said about communal-cultural life.

In addition to every existing party carrying on cultural and communal activities, there were also many institutions and societies that together helped in the intellectual development of the Jewish community. It is enough to mention the society for the founding of Jewish schools, the Jewish Association for Knowledge of the Country, or the already enumerated charitable societies which had a very great significance for the economic existence of the poor Jewish population.

Lublin had its own Jewish theater and its own daily newspaper, Di Lubliner Shtime [The Lublin Voice], which was published by the Bund. By the end, Lublin had two, even three Jewish-Polish gymnazies [secular secondary schools] in the city. Lublin proudly had a Y.L. Peretz School, a Tarbut [Zionist network of Hebrew language educational institutions] school, a Talmud Torah [free religious school for poor boys], and many khederim (Jewish elementary scholls). Additionally, the great Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva. Jewish printers who published not only newspapers but also published books.

Every week, a reading by a prominent Jewish figure drew a large audience. This was a period for the development of Jewish words, Jewish books, of Jewish culture.

Today this is all gone.

Only the memories of the past remain for us Jews, who personified the passionate Lublin Jewry. The murderers erased the people and everything from the surface that had a connection to the former Jewish Lublin

Please take note, Jews from all over the world and the surviving Jews of Lublin, that these additional published pages of our monument to Lublin Jewry reflect only a part of the life of a Jewish community in a city we can rightfully call a source of pride: the city and mother of Israel.

Translator's footnote:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lublin, Poland

Lublin, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Jan 2026 by JH