|

by Zev Sabatowski

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

In 1916, the First World War is in full swing. The fire surrounds almost the

entire European continent and both warring armies boast of their great

victories. It is believed that all kings and generals from both

sides will end as conquerors. However, it was no longer any secret that

it was the civilian population that would be the losers.

Each defeat and retreat of one army, or the victory and entrance of the

opposing army, brings with it new troubles and fresh fiats.

The winter had just now ended. The young spring carries out the last struggle with the yielding winter days. The taste of the coming summer had begun to be felt in the air and suddenly a typhus plague broke out. It had invaded suddenly and quickly spread to all parts of the city and among all layers of the population. The epidemic spread and from day to day the mortality grew with it. The entire population was seized by panic. As a result, our “good” Polish neighbors immediately found – as was the custom – that the cause of the plague is the Jews; Jewish impurity had brought the plague…

The “educated” anti-Semites claimed that the Jewish Torah acknowledges that the Jewish people are a dirty people, and therefore it was directed that every Jew must every morning, when he has just opened his eyes, pour water on his nails and run every Friday to the mikvah to wash himself. Is this not the most clear sign of impurity?…The claims were not very strongly supported. However, this was entirely enough to carry out a hostile incitement against the Jews…

The plague grows. There is no house where a sick person is not found. The Polish hospital is full and there is the threat of danger that the Jewish sick will have to remain in their homes and thereby increase the plague. Then a Jewish typhus hospital was created in a small wooden cabin near the crucifix, between Rolna, Stadalne and Wanwazawa Streets.

The management of the hospital was entrusted to the hands of Reb Yitzhak the butcher and his daughter, the large Gitl, as she was called in the city. They both, as well as the service staff, showed great devotion and self-sacrifice. Dr. Mitelman, of blessed memory, who had returned from the war as an invalid, throws himself into the rescue work with his entire soul and heart. He, as well as the good Jew and uncrowned doctor, Reb Moishe Fiszhaf, work day and night without thinking of the danger to themselves. A new type of “doctor,” Reb Mikhal Malamed, was revealed; he goes from sick person to sick person with warm consoling words that often affect the sick better than the medicines…

A short time after the founding of the hospital, in the very middle of the plague, Doctor Mitelman was wrenched away by typhus. This was a terrible blow for the hospital. The Austrian doctor Shweiger arrived in his place. He and his assistants employed all remedies to stop the plague, but nothing helped. Mortality among the Jewish population increased from day to day.Frume, good Jews did their part: the saying of Psalms did not stop;frume women ran to the Beis-Midrash every Monday and Thursday and measured white linen. The burning lights in theBeis-Midrash, for the dying people, did not go out. However, all of the remedies and Psalms did not stop the plague and the Angel of Death raged further. When his arm reached the victim, RebShamas, some found a sign in his death, that this would be the last victim of the plague. However, it was immediately apparent that this was a false consolation. People again fell like birds. When the second victim, Reb Yosef Safkewer, also died, the turmoil in the city reached its highest point. The Beis-Midrash filled with the reciting of Psalm, there was fasting and Yom-Kippur Kotn (fast on last day of the month). There was both no Jewish doctor and no gravedigger…

Turmoil completely reigned over the city during the plague and the idea was born to undertake the last remedy: to celebrate a wedding at the cemetery. Good Jews and frume Jewish women began to search intensely for a groom with a bride who would agree to erect their khupe on the cemetery. After a long search and groping, first the bride was finally found. A poor widow with a half dozen over-age daughters lived in Moishe Kalka's house, near the second Bridge of Forgiveness. One of her daughters was chosen as the proper cemetery bride. But try to make a wedding with just a bride… The city matchmakers decided that a groom must be found at any price. An offensive was literally begun in order to catch a groom. Taking part in this offensive were the well-known social worker Brandele Rapoport, Minchele the Rebbitzin, Fagele the Kupke (Translator's note: a kupke is a bonnet worn by pious women.), Israel Yekl's Hinde, Hercki's Perl, Gele the baker, Khua Ajzen, Ruchla Hamer and the pious woman from themikvah. Eventually a groom was successfully found, an exquisite one with a nice father.

[Page 155]

Who did not know Moishele the glove maker and his son Shimele? The father with

his foolish laughing face, with the two wooden cans over his shoulders was a

frequent visitor to the wealthy houses, with full buckets of water from the

city pump. In addition, he was a fervid Hasid of the Radomsker Rebbe Reb

Shlomoh Henekh. Moishele, the groom, was not satisfied with one rebbe,

but every Shabbos he would chose another rebbe. Shabbos Bereishis

he davened in the Gerer shtibl and ate with a Gerer Hasid.Shabbos Noakh

he went again to daven in the Sakhoczewershtibl and spend Shabbos

with a Sakhoczewer Hasid. Thus he changed rabbis fromShabbos

to Shabbos and also the Shabbos meals with their Hasidim. In brief,

an appropriate groom…

In short, there is already with luck a groom with a bride. However, here an episode began: a bride needs a dress, a pair of shoes for the wedding. The groom again must have a pair of pants, a frock coat, a pair of boots. In addition, Shlomoh-Yitzhak Epsztajn, the city wit, whispered in the groom's ear that he does not have to go the khupe until he receives payment of the dowry. That means, Shimele, he reasoned with him, you have such rich in-laws: Yosef Najkron, Haim Eichner, Abrahamele Klajner, Meir and Daniel and Yakov RichtermanRozenbaum, Israel Richterman, Shlomoh Lewkowicz, Dovid Bugajski, Lajzer Tencer, Shimon Dunski, Moishe Lewkowicz, Shabtai and Yitzhak Fajerman, and other wealthy men. So how can you go to thekhupe without a beautiful, large dowry?… These words were very successful with Shimele and he spoke such invective, “I will not take the bride without a dowry, and let the plague continue to do its…”

There was no other choice. The social workers set out over the city, going from house to house and began to drag old candlesticks, torn shirts, patched blanket covers, washed out bed linens, secondhand tablecloths and what else?… With luck, a house was rented on Krakower Street and a pair of old beds and a lame table with a few broken chairs was placed there. Everything was finished and the city waited with beating hearts for the khupe day, which would deliver the city from the terrible plague.

It was a Tuesday morning; silence reigned over the streets. The first twofrume women appear in the street and with quick steps they go in the direction of the bride's apartment. The bride has become stubborn and will not go into themikvah. The two frume women turn to all of their resources and after great effort they succeeded in taking her, in order for her to fulfill the holymitzvah of ritual purification.

The clock goes at its normal pace. The city wakes from sleep; the ring of the church bells is heard. Several businessmen dressed in pressed silk frock coats and in thick soft boots, talis and tefilin under their arms, stride in the direction of the cemetery. Today thedavening goes quickly; all prepare themselves for the great wedding.

It is already 12 noon. The public begins to gather and people flow from all streets. Here floats the old “Leibele Klezmer;” he is dressed up as for the wedding of a wealthy daughter. Here, with measured steps, goes Reb Moishe Lewkowicz, the founder of the Zionist organization in Radomsk. Skurke the Batkhn (the humorous wedding entertainer), or as he was called “the comb-maker,” goes and jokes at the expense of the young pair. Around 2 o'clock p.m., the entire city is in one place.

Kopl, the Beis-Midrash Shamas, sweating as if in a hot bath, divides the orders like a general on the front, but who hears him? All are curious to see the frightened groom, who stands, nebekh, and trembles. Near him stands his closest relative, his father Moishele, and his face shines with a foolish smile. Suddenly, as if on command, the music plays. It becomes a race; everyone wants to see the covering of the bride, who is quartered with the Radomsker Rebbe in his house. With the ringing of the thunderous music, the procession heads from Shul Street to the cemetery. Large and small accompany the groom and bride to the khupe. The crowd was so large that it is only thanks to the city-bullies that took over the guarding of the groom and bride that there remained someone to be married…

At a lucky hour, the groom and bride and their attendants arrive at the cemetery. Everything suddenly becomes still and a mystical fear grips the crowd. Four sticks, which Leibish – Shamas brought with him, are quickly raised not far from the ohel. The silent crowd listens to the fiery voice of the wedding officiate and the groom is heard repeating in the voice of a sobbing child the “Behold thou art consecrated.” The breaking of glasses is heard and immediately after, cries of mazel-tov and good wishes deafen the cemetery. The young couple is led back to the city.

Now the true celebration begins. The tables in the communityBeis-Midrash are covered. The best businessmen sit around them, gratified with a little liquor and good things that were prepared. The music plays, The batkhn is heard and begins to announce wedding presents. The crowd gives, some more, some less; no one refuses to give a wedding present to the groom and bride. There is no lack of pranksters who honor the groom from afar with the head of a herring or, at random, with a rag. The young people make a racket. Kopl-Shamas runs around with an open shirt and yells that troublemakers will make a ruin of the Beis-Midrash.

In the morning, the city has returned to normal. After the wedding, a relief is

felt in the heart, as if a heavy burden had been thrown from the shoulders.

And, in the middle of the market, near the city pump, again appeared the ruddy,

gentle young man with two brand new cans ringed with gleaming tin hoops…

[Page 156]

by Yakob Elboim

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Leibele the “Water Carrier,” that's how we called him. He was truly a

water carrier and not just a nobody, with a good lineage that stemmed all the

way from the era of Tiferes Shlomoh. Leibele's grandfather, Reb Nute, carried water

forTiferes Shlomoh, of blessed memory, for many years. What's more, Leibele with his pack would

boast when the women would call after him: “Where is the water

already?” He would stare at them, spread his feet wide, open his mouth and

draw out a sort of sermon: “What do you mean! Don't you know then that

these water cans are holy? That with these water cans my grandfather Reb Nute

would fill the barrel for Tiferes Shlomoh in the Beis-Hamedrish

! With the water from these water cans the rabbi, of blessed memory, washed his

hands and so did the hundreds of Hassidim. Now you come, impertinent ones, and

want water from these same water cans. This is blasphemy!…”

(Translator's note: There seems to be a discrepancy in the identification of the water carrier. Here he is referred to as Leibele; in the section entitled “I Bid Farewell to My Hometown,” his name is given as Velvele.)

These holy water cans of Reb Nute were given as an inheritance to his son Mikhal, Leibele's father. Mikhal the water carrier provided water for the later rabbis of the Radomsker dynasty. But Mikhal would provide water for plain families and would not speak about the lineage of his water cans the way his heir Leibele later.

Poor women would always run after Mikhal's water cans because they were large and always full. Mikhal was a very accessible person and would converse with his women customers; he would also boast that in his pouch he always carried with him a share of the Colonial Bank for Eretz-Yisroel. He was a “lover of Zion” and a regular donor to Keren Kayemet Le-Yisrael (Jewish National Fund).

|

| Leibele the water carrier and his wife |

Reb Mikhal, of course, strove to assure that the family lineage as water carriers would not be interrupted. Consequently, he began to teach his son Leibele, who was not blessed with sense, or in his outward appearance. The father understood that the son would not abandon the water cans and through the water cans would come his son's survival and he proceeded straightaway to protect the right of inheritance from grandfather and father.

From childhood, Leibele was called Leibele the Fool. No beard or whiskers grew on him; his voice was not like that of a male. His face always exhibited tears or laughter. His garb was always strange, one pants leg shorter than the other, the under clothing longer and the outer, shorter. When he was 50, he was still single…

A gang of youngsters would always run after Leibele and scream after [him]: “Leibele the Fool, Leibele the Maiden, you want a bride?…” The kids would pull him by the clothing, empty the water cans and pelt them with mud. In the first minutes he would get angry, throw his fists and pour curses, but within a couple of minutes he would break out with a lamenting cry. Then the kids would leave him alone, circle him from all sides, their faces expressing pity and remorse. Leibele would calm himself, lift up his empty water cans and again stride to the well, accompanied by looks of sympathy and sorrow. But when he returned later with full water cans, the whole spectacle would start again…

Leibele suffered this way for ten years, as an accursed soul who carries a curse from God, until a ray of light brightened his dark fate. At the end of the First World War he was saved from his long years of shame and mockery – he got married. It was a public wedding, a wedding that the whole city celebrated, with in-laws and best man, with klezmorim and wedding jesters, with wedding presents and a lavish banquet. After such a wedding, Leibele remained a water carrier, but no longer, Leibele the Fool, Leibele the Maiden…

Such a popular Jewish type like the water carrier, or even the City Fools whom

children and grownups laughed at – added special local color to the city

and fused into the general way of life as a natural phenomenon. It is

interesting that if these very types didn't exist in the past, it would make

our current memoirs colorless, because they would lack the vital local

coloration of our own local popular Jewish characters.

[Page 157]

by Izrael Merkin

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Israel Merkin was born in 1901 in Radomsk and later was active there inHashomer Hatzair.

He began acting in Poland (in 1931) and later emigrated to Argentina (1935). There he

frequented the dramatic school of the Yiddish Artist's Union and joined (in 1936) the Yiddish Dramatic

Theatrical Studio.

Israel Merkin advertised himself as an actor through the roles he filled well:

Erwin – “Revolt in the House of Correction;” Rubinchik –

“200,000;” Bill – “Mississippi;” Nikitin –

“The Life Calls;” Yosele – Boytre; Der Meshugener

(The Crazy Person) – “In the Anteroom of the Synagogue;”

Charni – “The Deluge;” and many others.

We present here two small chapters of the memoirs of Israel Merkin, of his youth in Radomsk.

“Damski” – the Singing Painter

He was called “Damski” (Trans. Note: from the Polish word dama,” lady). No one knew his real name, in fact it never occurred to anyone to ask, and he was called “Damski” because his walk was more like a woman's than a man's. He would not walk, but truly floated in the air: slender, flexible, with a great black forelock that was always disheveled and with a pair of dark eyes that were always smiling.

Throughout the year, no one knew how he was employed; no one asked him. However, when the first spring rays began to melt the snow and announce that Passover was presently creeping up and women began to think about painting their poor houses, then “Damski” would appear in his full splendor in a pair of narrow, short pants, from which two thin legs looked out, a ladder thrown over his shoulders, two buckets by his side, his face smeared so that his eyes were not seen – “Damski” marched singing a little or only whistling some melody, as was his manner.

“Damski” was a painter, and a painter not of the usual kind. It was known that besides the work tools that he brought with him, he brought much joyfulness. Besides painting, “Damski” mightily loved to sing and he would sing while standing on his ladder and he would truly make the ceiling shake. Children would climb the windows, neighbors would run together from the nearby houses – listening to how “Damski” sang his romances…And as “Damski” would see that his audience near the window got larger, he would then show what he was capable of; he would then go down from the ladder, crouch down and kick with his thin legs, carrying out some sort of strange dance and wink delightedly with his eyes. Mostly, he would sing the reprise from the little song: “Pinye from Pinczew!” “Pinye from Pinczew!…”

|

| “Damski” |

If the work was above his head and it was necessary to do it still more

hastily, “Damski” would quickly ask that the few possessions

be carried out and with an earnest face begin to prepare to

paint. However, as soon as “Damski” would make the

first few smears and end the first little melody, he would disappear as

if into water – thus in one house, and thus in a second… Thus one

could see more than once, the way women run after him, “'Damskele,'

you have lathered me up [and left me half shaven], you should be swept

away!” And it very often happened that not just one woman spent the night

in the street because of him.

However, his lazy little pranks were not always successful. There were also woman “Cossacks,” who as soon as “Damski” would cross the threshold, would lock him in the house. Then “Damski” had no choice and had to finish the work. In such cases, “Damski” would become part of the family – eating with them and spending the night and feeling as if with his father in the vineyard. And when “Damski” with luck would finish his painting, one could then rightly admire his talent. One recognized immediately that “Damski” does follow the regular rules of painting; he had his artistic instinct. He then probably foresaw the later “isms,” which sprang up in modern painting. The long lines of flowers, with which one loved to adorn all of the houses, would with him stretch from the ceiling to the floor and instead of coming out even, with him they came out crooked, falling. As one would enter a house, it could seem that the house because of its oldness had become twisted…

The women would not have redress for their complaints about the crooked lines. To all unsatisfied groans, “Damski” would whistle a tune or sing his famous “Pinye from Pinczew!'… True, from his song, the lines of flowers did not straighten out. However, who tried to argue with him? One would pay him his craft money. He would wish a “freilekhn Pesakh (joyous Passover) and one should live until next year,” and with his strange way of walking, leave the house. The children would run after him and shout, “Damski!” “Damski!”

Where are you today,

Where are you today, “Damski”?

[Page 158]

A Sacrifice for a Little Sand in Honor of Shabbos

Every erev-Shabbos the “foul-mouthed ones” (the gentiles) in Radomsk brought sand into the city to sell to the Jews for spreading over the floors, which brought a brightness to the house. The golden sand was taken from the sandpit in the “Gliankes.”

During the First World War, in 1914, great poverty reigned among the Jewish population in Radomsk. And in our house, too, the poverty was very strongly felt. My father created various artistic birds and from this he drew his income. During the time of the war, mainly at the beginning, the troops changed often: Here the Russians, here the Germans, and then the Russians again, and the Austrians. Battles also took place around Radomsk, so that it was impossible to leave the city in order to sell the beautiful birds among the population in the villages.

On a certain Friday morning, when my mother did not have a few groshn with which to buy the little box of sand, she told my older brother Zalel, that he should take a small sack with him to kheder and coming back fromkheder, he should bring a little sand from the “Gliankes” to spread in the house in honor of Shabbos.

My mother was uneasy about her child during the whole time and already regretted that she had asked him to bring sand from so far away. When the time arrived that Zalel should have already been back and he still was not in the house, the uneasiness spread. We went out into the street with the hope that, perhaps, someone had seen the child. Alas, no one knew where the child was.

My father, coming into the house from the street, learned what had happened and immediately ran to the sandpit. Not receiving a precise answer from the “sand gentiles,” he called loudly, “Zalel! Zalel! Speak up, where are you?” However, he did not receive any answer. Then, already in the darkness of nightfall, he began to dig away the sand with his hands, deeper and deeper, until his hands found a human body – this was my unlucky brother Zalel. My father carried the dead body and, accompanied by hundreds of Jews, brought him back to the house.

It was a Shabbos of crying and wails; the entire shtetl was taken over with our misfortune. It was clear to all that the “sand gentiles” had murdered him because he wanted to take a little sand himself.

Months later, on a Friday afternoon, a Pole stood near our house near a peasant's wagon filled with sand. Suddenly, an Austrian soldier rode up and requested that the Pole ride with him because he needed the horse and the wagon for pawade (what we called the wagons and horses that were often taken over). When the “foul mouthed one” refused, the soldier fired his revolver and the sandman lay dead. Many Jews declared that the Pole who was shot was the same one who had murdered my brother Zalel, of blessed memory, and now he had received his just punishment; God does not pardon anyone for the sin of murder.

Years later, when I was already in Argentina, not long before the outbreak of the Second World War, I read a report from Poland, that in Bydgoszcz, near Poznan, a trial is taking place against a young Jewish man, who served in the Austrian military in the First World War and who had then shot a peasant in Radomsk. This is certainly that unknown young Jewish man, who had unconsciously taken revenge for the innocent blood spilled by my brother Zalel, the sacrifice for a little bit of sand in honor of Shabbos…

In the Beis-Hamedrish of Reb Shlomoh Hacohen of Radomsk (the Tiferes-Shlomoh) it once happened that the Shofar blower, a great scholar, a Hasid and God-fearing person got so “stuck” at the very beginning of the tkies (one of sounds of the Shofar) that he could not bring any sound out of the Shofar. The Tiferes-Shlomoh called out from among the prayers a young man and this one took the Shofar and blew a whole series of tkies the way it should be, with a clean and beautiful sound.

After davening Reb Shlomoh Hacohen called over the “failed”Shofar blower and said to him: “I want to tell you a little story. In a certain land a new crown set with pearls and diamonds for the king was ordered from an experienced master. The master locked himself in his workshop for a whole month, thinking about how best to carry out the responsible work. A day before the coronation, when the work plan was already clearly thought out in his mind, he took the crown and wanted to set the expensive stones. However, at that moment a great fear came over him and he felt as if his strength was leaving him…

The master called out from his workshop to a passing youth, who had no idea how to do the work or for whom the work needed to be done. He handed the crown to the youth, showed him exactly where and how to set the rare stones and left to refresh himself after his great consternation. When he returned to his workshop after a short time, the crown was finished in the best way…

| In the Beis-Hamedrish of Reb Shlomoh Hacohen of Radomsk (the

Tiferes-Shlomoh) it once happened that the Shofar blower,

a great scholar, a Hasid and God-fearing person got so “stuck" at the

very beginning of the tkies (one of sounds of the Shofar)

that he could not bring any sound out of the Shofar. TheTiferes-Shlomoh

called out from among the prayers a young man and this one took the Shofar

and blew a whole series oftkies the way it should be, with a clean and beautiful sound.

After davening Reb Shlomoh Hacohen called over the “failed"Shofar blower and said to him: “I want to tell you a little story. In a certain land a new crown set with pearls and diamonds for the king was ordered from an experienced master. The master locked himself in his workshop for a whole month, thinking about how best to carry out the responsible work. A day before the coronation, when the work plan was already clearly thought out in his mind, he took the crown and wanted to set the expensive stones. However, at that moment a great fear came over him and he felt as if his strength was leaving him… The master called out from his workshop to a passing youth, who had no idea how to do the work or for whom the work needed to be done. He handed the crown to the youth, showed him exactly where and how to set the rare stones and left to refresh himself after his great consternation. When he returned to his workshop after a short time, the crown was finished in the best way…

|

| (Book of Hasidim about Tiferes Shlomoh) |

by Dawid Koniecpoler

(Dedicated to the memory of my father, Solomon Ber, Tzadek of blessed memory)

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

The city shul in Radomsk was built in the last two decades of the 19th

century. It was a major effort of the whole city community working together.

The shul was built very spaciously: two entrances on the front side and two entrances

on the other sides served the men's shul, in which were found more than 600

seats. Two wide staircase entries led to the women's section in the shul,

which was created with a generous hand. The anteroom of the synagogue

consisted of two big rooms, which served to tie together the council of theshul

and, when it was necessary, the courtyard for smaller groups of worshippers.

Great efforts were made by the group of artisans in constructing the shul. Many people were concerned just with the voluntary efforts of the handicraft workers in building the shul. Young artisans worked for months completing the interior of the men's shul, while also completing the beautiful galleries in the women'sshul.

The shul was a very important object in our childhood. We were here in theyom-tovidiker and Shabbosdiker days together with our parents. We davened and drew into ourselves the beautiful folk melodies of Hazan (Cantor) Reb Shlomoh Zaks and, after his death, of his successors, like H. Fiszel with his large choir (led by a special conductor), as well as otherhazonim (cantors).

During the first years, the ceiling of the shul was painted by the Gentile painter H. Mike and it showed a sky with stars. A large eagle fluttered over the Holy Ark and for almost the whole length on both of its sides. The 12 signs of the Zodiac were painted, arranged according to the months. Later the amazingly beautiful Holy Ark was built. It was executed by the tombstone engraver, H. Reich, together with a group of Warsaw carpenters and wood carvers. Everything was made of white wood with many carved elements. And very impressive was the cupola over the doors of the Holy Ark, which was donated by the Reichman family of Piotrkow.

Finely carved bows were found on the carved barriers by the sides of the steps to the Holy Ark. Members of the extreme religious circles scratched out the bows with pocketknives, because they looked like crosses. Large chandeliers that created a distinct dignified mood in the general warmth of the shul hung down from the ceiling.

|

|

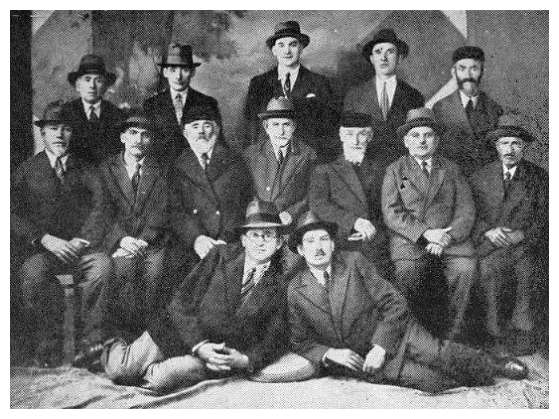

The Vaad (Ruling Council) of the Great Synagogue (1930)

Standing from the right:

|

In 1905/8 revolutionary Jewish workers parties used the shul

onShabbos and Yom-tovim for enlightening lectures from time to time.

Anyone who opposed their activities was placed under the pressure of arms.

Then the Radomsker Rabbi Reb Tsvi-Meir Rabinowicz, of blessed memory,

created the group Mishmoyres Hakodesh (Holy Guards) that was made

up of 12 men (with Rabbi Brasz) like the 12 tribes. They were businessmen

and artisans who were active in building the shul and their task was to

protectShabbos and yom-tov so that the davening would not be disrupted

by the revolutionaries.

A special eternal light was fitted in the shul that represented a four-corned stone (4 meters high) with a copper oil lamp at the point. In the stone was fitted a marble panel with the engraved names of the donors and friends of the group Mishmoyres Hakodesh and their chairman.

After the death of my father, Reb Dovid Burstzyn brought to us at home thePinkes (Book of Records) of the Mishmoyres Hakodesh. It consisted of twelve pages, on which there was written in a beautiful penmanship, all of the names of the group and of the members of the group (with the years of their birth). I then wrote the date and year when my father died, because he was a member of the Mishmoyres Hakodesh.

In my memories swim images of gatherings with Rebbe Tzvi-Meir Rabinowicz of blessed memory, in his apartment on Shul Street (we children would receive an apple and a pinch in the cheek from the Reb). Later these gatherings took place with the Hazan Reb Shlomoh Zaks, of blessed memory. During the Days of Awe when all of the Hasidim would gather with the Radomsker Rebbe, there was a tradition that a large number of Hasidim would come into the shul for Musef, to hear the Hazan with his choir. This was during the time when there was a break between Shakhres (the morning service) andMusef (the extension of the morning service on Shabbos or duringyom-tovim) at the Rebbe's. At that time gatherings of Jews filled theshul auditorium.

The shul was used for solemn presentations by various Jews, such as lectures on national and Palestinian themes.

Years ran by, Jewish blood was shed, millions of our people were exterminated and all of our holy places were vandalized and annihilated. We stood in 1947, a small group of survivors, in the destroyed shul in Radomsk – bent by a great sorrow and pain. Our glances wandering over the wall. Caressing the vestige of the Holy Ark and the reading desk, the artistic inscription from the prayers on the wall. We remember: Just here sat the Rabbi and here the warden of the synagogue, here my father and here your next-door neighbor…

Suddenly my gaze falls on the top of a stone, which sticks out of the ground and I recognize that this is a part of the eternal light. We dig out a little earth and there appear before our eyes inscriptions that we recognize… And in that moment filled with sorrow, we were dominated by the thought: This is a sign that our enemies were not successful in exterminating our people; the eternal light that was here dirtied will somewhere else give light again…

The Eternal God of Israel does not forget.

[Page 160]

|

|

|

|

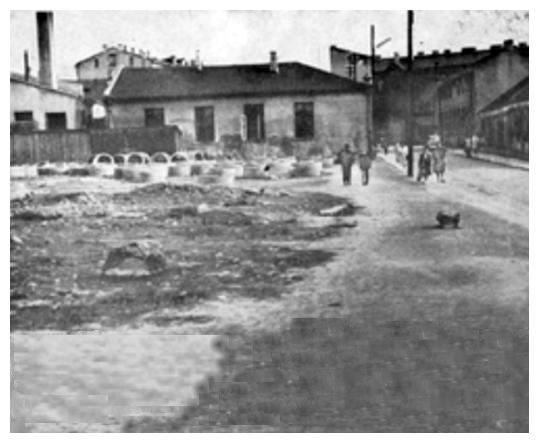

The front wall of the Great Synagogue,

the only wall that was left after the [Holocaust] (1945) |

The photograph was sent through the Radomsk City Hall in 1965

and here is seen only the ruins (in foreground on the left) of the Great Synagogue. In the background from the left is the house in which was found 'Kopel's Besmedresh' (prayer and study house) and on the right, the house in which the Amshinower Rebbe lived. |

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Radomsko, Poland

Radomsko, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 17 Nov 2025 by OR