Water Sport

|

by Shlomo Zeira

Translated by Sara Mages

As if through a thick fog, I now see the times in which I spent my early

childhood years in Radomsk. I left the city when I was young, and in the

meantime the images of the people who surrounded me during those years have

become blurred.

I will confess and not be ashamed that in the years of my adolescence, during the pioneering period in Eretz Yisrael, I almost tried to forget these good people, their surroundings, conversation, occupations and good and bad attributes.

Today, as you turn your thoughts to “there” and “then,” a unique light may appear to you through the heavy fog. This light is the generation that lived during your childhood. In the twilight period, during the decline of “ancient” Judaism, which sighed under the yoke of the Diaspora and awaited the Messiah who would come riding on a donkey, and during the rise of new Judaism, a Judaism of self-liberation.

It is difficult to put on paper the memory of all those who deserve it, because there are so many of them. And when I speak of them, I will remember them and feel compassion for them. In the following lines I will try to sketch a few figures whose memory, for some reason, is engraved deep in my heart.

The first sounds of Hatikvah

If I am not mistaken, my parents' first apartment was in Adolf Lewkowicz's house in a street that crossed the railroad tracks – Breznicka Street.

The homeowner, Mr. Adolf Lewkowicz, had a trumpet similar to the one used by the city fire department. On summer evenings, Mr. Adolf used to play a new melody on his trumpet, the content and meaning of which I did not understand at the time. This was not a synagogue tune (I don't think Mr. Adolf was a synagogue goer at all…), not a Jewish folk song, but something new. Only after a certain time I accidentally learnt the nature of the melody and its origin, and that elevated Mr. Adolf the highest level. And the story was as follows.

In 1906 – if I am not mistaken – a “state of emergency” was declared in the city. A strict curfew was imposed on the entire city starting at eight in the evening. Anyone, who dared to be seen on the street after this hour, risked being arrested by the Cossack cavalry guards and even got a taste of the Russian Cossack whip. One evening I was at my grandfather Reb Yehezkel z”l, and close to eight in the evening I returned home accompanied by Mr. Felman, who lived in the neighboring house. When we were already a few dozen meters from the house, we heard the sound of horse hooves and a shout: Stop! We started running. We still managed to enter the gate of Mr. Felman's house and to lock it behind us. A second later, a Cossack banged his rifle butt on the gate and shouted: “open! If you don't – I will shoot!” Frightened and trembling, we stood in our places and remained silent. After the soldier had left, and silence had settled on the street, my escort opened the door, took me outside, and ordered me to walk slowly home. With a trembling heart I arrived at the Lewkowicz house where we lived. The homeowner met me in the yard and was surprised that I had come during curfew. I told him about the incident and ended with a sigh, “Oh!” He approached me and whispered in my ear: “you are still young. You may still be blessed with living in Eretz Yisrael.” In my innocence, the innocence of a four-year-old boy, I asked him: “will the Messiah come?” “He will certainly come! – he answered me.” “Don't you sometimes hear my trumpet? it's his shofar” – he ended the conversation. I thought he was mocking me. It was only two years later that I learned that the trumpet melody was the song “Hatikvah.”

Blue-beard Workers

The author, Maurice Maeterlinck, wrote “The Blue Bird,” and other poets sometimes speak metaphorically about “blue blood,” while I saw, with my own eyes, Jewish workers and their and the hair of their beards – was blue.

When I was a little boy, I occasionally visited the home of my grandfather Reb Hershele z”l. And in the yard, to my amazement, I came across Jews with blue beards and blue mustaches. It took a long time for me to understand the meaning of this. In my grandfather's yard was a small factory for ultramarine “sticks,” a blue dye for laundry. While kneading the blue dough and cutting it into sticks, the beards also absorbed the blue powder and took on the light blue hue, and so Jewish workers appeared with blue beards and mustaches.

By the way, I once heard from my grandfather that Friedrich Bayer the German, founder of the renowned Bayer company for dye and pharmaceutical, once came to Radomsk and offered him, or his father, grandfather R' Moshe, to build in a partnership a factory for ultramarine dye in Radomsk. The intention was to save on the high customs duties that the Russians imposed on German goods. Grandfather did not accept his offer, and the factory was built in a small town near the city of Riga.

The persistent

The transitional period of changing values among local youth began immediately with the entry of the German army to the city during the First World War. Many young men, who until then had been influenced by tradition and the Talmud and never looked at Haskalah books, now turned to secular studies openly and publicly. Some of them were enthusiastically drawn to the problems of time, to Zionism or to the Bund. While others turned to studies to obtain a diploma. Of course, their traditional education, their interrupted studies and even their age prevented them from achieving their goal. Only a few reached their goal thanks to their great perseverance and endurance. One of them was my friend Yakov Aronowicz (later a Doctor of Medicine in Radomsk). Even though he was a few years older than me, he tended to engage me in conversations about his studies in general and specific issues in particular. For him, studies were not a burden imposed on him from above, to be tested and then released from, as is customary for schoolchildren. For him, studying was an experience, a kind of spiritual pleasure, which not everyone gets to experience, let alone understand properly. He tackled every issue light as severe, every section and verse as a kind of material, and everything that is understandable, simple, and natural to an ordinary student was for him a kind of special revelation, which should be blessed by mentioning the name and title of God.

We both left the city on the same train abroad. (A month earlier we had been in Piotrków to obtain permission to travel abroad as students. We were examined by a veteran army officer who wanted to know why we wanted to study abroad. I answered him very briefly while Yakov spread out a broad canvas before him about education and enlightenment, almost revealing to him what he should not have revealed… The old man was impressed by the enthusiastic scholar and approved his departure abroad.) Anyone who hasn't seen Yakov's joy on his train trip to Switzerland to study has never seen the joy of a happy person. Due to his busy conversation with other passengers, he neglected his luggage, and when we arrived in the city of Posen, he was informed that his luggage had not arrived. I waited in this city for twenty-four hours in the hope that in the meantime the lost luggage would be found, and we could continue our journey together. But the luggage never arrived and we parted ways. That was our last conversation. He continued his studies and several years later was certified as a Doctor of Medicine.

The educated

There was a Jewish man in Radomsk, humble and modest, and his name Mendel Feinzylber. A learned man of a good family. He mastered the treasure of our ancient and modern literature and the Hebrew language and was accepted as an outstanding scholar. His livelihood was from a small shop. But, in fact, it was an occupation with nothing to do with the subject at hand. His main occupation was the research of the Bible, literature and philosophy.

Sometime after the city was conquered by the Austrians, I was able to obtain

permission

[Page 130]

to travel to the city of Piotrków and told one of my friends about. The

next day, early in the morning, my friend came to me with a big request, not,

God forbid, for him, but on an urgent matter concerning the aforementioned

Mendel.

I responded to his pleas, and we approached him. Mendel Feinzylber, that this was my first meeting with him, took me aside and with awe and reverence told me that he had not slept for months because a serious problem, originating from the Bible, is tormenting him. Since, in his opinion, there is a Jew in Piotrków (if I am not mistaken, his name was Pinchas Baron, who later immigrated to Israel) who can explain the problem to him. He asked me to go to him, give him the letter and get a reply from him. In Piotrków I looked for the scholar and found him in a small shabby apartment. Before me stood a Jew dressed in long robes and with the dignified appearance of a learned scholar. I gave him the letter. He immediately got down to work, read this book and that book, and finally wrote a reply to the Radomsker scholar.

My friend, who gave Mendel Feinzylber the letter, told me later that on that day he did not work in his shop. He locked himself in his room to digest the contents of the letter.

The exemplary stubborn

Nachman Tzvi Gold-Paz z”l was a distinctly stubborn man. His stubbornness knew no bounds. It was not just impulsive stubbornness, but a stubborn will: to overcome the wickedness of man, difficulties in school or work, and even the laws of nature. (once, I met him on a day of heavy heatwave. He was sitting next to a huge jug of water and from time to time took big sips from it. Of course, he immediately emitted the water by sweating. I asked him, “Well, what's the point of drinking so much water?” “I want to overcome the power of the heatwave. Let's see who will be stronger!” – he answered me).

Throughout the years we knew each other in Israel, it seemed to me that his main goal in life was to fight and win. Indeed, he was a man of extraordinary courage, and I hardly knew anyone like him. When he found a cause that was, in his opinion, worthy of fighting for or discovered a burden that needed to be uprooted – no struggle was too difficult for him, and he accepted all the suffering of the war until its end.

There is not enough space here to recount even some of his actions in this area. I will settle for just two episodes. He told me about one while I heard about the second a while ago from Y. Marminsky, member of the Histadrut Executive Committee.

With the entrance of the Austrian army to the city in 1915, they began to grab people for fortifications work. Whoever was caught saw this as a royal decree and resigned himself to it until the danger had passed. Not so the hero in question, Nachman Tzvi. He thought and found that, according to fairness and justice, the occupying army did not have permission to do so, and when he was caught, he evaded the military policeman and fled. Apparently, the policeman was also stubborn and chased him, and the matter developed into a dramatic escape and pursuit. That is: from the street to the yard, from the yard to the house and from there to the roof, and from this roof to the roof of the neighboring house until Nachman Tzvi was caught and taken to work. But that was not the end of the matter. He had to show up for work again the next morning. Since he did not show up, the policeman went to him. As soon as the door opened and the “shining button” entered, Nachman Tzvi immediately made a great escape. The policeman ran after him from alley to alley, building to building, and from rooftop to rooftop until he finally fell into the policeman's hands. and this time he received a severe beating. At the end of the beating the policeman spat and said, “May the devil take you, you damned Jew! Go to hell! I don't want to see you anymore.”

In 1920, Nachman made aliyah to Israel. In this group of halutzim [pioneers] was also Y. Marminsky, Leib Goldsmidt z”l from Kibbutz Ein Harod and others. In Vienna, the first stop on the way, news arrived of the numerous cases of malaria in Israel and the acute shortage of quinine. With the help of friends a loan at the amount of three thousand dollars was obtained, and a quantity of quinine was purchased.

At that time, the export of quinine from Vienna was prohibited by the authorities. At midnight, the Austrian police burst into the hotel where our halutzim were staying, went straight into Nachman Tzvi's room, and demanded him to hand over the quinine. But when Nachman Tzvi claimed that he had neither seen nor heard anything about quinine they began to beat him severely. He responded to this with terrible shouts in Hebrew: “Scatter! Scatter!” It was a signal for his friends to escape. The police beat him for about two hours, and he continued: scatter! In the end they let him go and the shipment reached Israel (by the way, when they opened the bags in Yafo instead of quinine – they found sand in them …).

The proverb cited in the Midrash, “when they lifted the pottery, the pearl was found,” was fulfilled in Nachman Tzvi. Underneath his tough exterior was a heart sensitive to all who were oppressed and in need. Dozens of people living with us in Israel owe him gratitude for the loyal, moral, and material help he had given them. He was a good friend, a good person to hang out with, a grounded, solid character. Although he did not polish his tongue when he talked with others, and even less so with his opponent, he did not know the language of smoothness and perhaps was not endowed with manners of behavior in a society other than his own. But these were like thin grooves in a block of marble or basalt.

A friend who closely knew Nachman Tzvi told me some time ago: “If we had fifty people in this country today like Nachman Tzvi Gold, we might not be witnessing the social crisis that is prevailing in the country…”

Water Sport

by Morris Schwartz

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

|

| An Interview with the

Oldest Landsleit in America Abraham Leizer Gliksman (my maternal grandfather) |

On a cold day, in December, I knocked on the door of our landsman.

Unfortunately, I found him sick in bed, very weak.

– Sholem Aleichem, Moishele! He called out.

– Reb Abraham Leizer! - I said - Aren't you ashamed, you the bal-koiek (man of strength) are making yourself foolish and lying in bed.

– You are right, my child.

– Reb Abraham-Leizer! I have come to you; first, to obtain a greeting from you to our native-city, because we are publishing a book, in which each countryman can write their life history [and] send a greeting to Radomsk. Secondly, [I want you to] tell me stories about the past, about the old times and I will put them in our book.

His eyes lit up, red color appeared on his cheeks. “I remember a lot of things, but what comes of it - I haven't any strength,” and with a weak voice started to relate:

“90 years ago, Radomsk was not a city. It was called a 'treife-moekm' (unclean place). Jewish Radomsk was in Bugaj. A 'Mura-Tzadek' (a righteous man). The mikvah was there. The leaders then were: Yosel Tsaduk, and Sore-Dwojre, Yosel Hampel's wife. The rich men lived in Plawno (Reichman, Richterman, Banker, Besterman, Hasenberg). After the coronation, in 1863, when Aleksander II ascended the throne, Radomsk became a Jewish city. By day Jews traded in the city and at night they went home to Bugaj. Or traveled to Plawno, because they were not permitted to live in the city or stay the night.

From Radomsk, whiskey and meat were smuggled into Bugaj. At that time there were Moishe the watchman and Ahron 'Farenkishke,' also a watchman. Later the czar permitted Jews to live in the city, but they were not permitted to buy houses in their own name. They bought houses using goyishe names. Not until Alexander II ascended the throne were Jews permitted to buy houses.

The community leaders at that time were: Leizer Ricterman, Izrael Zilberszac, and his wife Hodel (she was a saintly woman; [she] always had 8 guests at her table), also Berish Feszter and old Abraham Bem.

Later new rich men arrived: Dawid Bugajski built the new shul; Banker and Ferszter laid the first foundation; Izrael Ricterman renovated the old Beis-Midrash (prayer and study house). Bernard Feszter was the most respected Jew in the city. He would daven next to the rabbi, and was the gabbai (trustee) of the burial society. On Shimkas Torahi, it was a tradition to dance on a board, to make a procession and carry the Torah around the shul. Feszter once said to Berl the shamas (rabbi's assistant): 'Let the or people carry the Torah' - but he never said to given them beer…

Abraham-Leizer told me more wonderful stories: about Rabbi Reb Ber of

Radoszyce, about Josef, Gabrial, Izrael Zilberszac, about Khesed (benevolent)

Abraham, of blessed memory, about Tifires Solomon of blessed memory and

about others.”

by Sarah Hamer-Jakhlin

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Often when I am alone by myself and think of my childhood and of my hometown, a

long forgotten curtain lifts up for me. It takes the shape of the dear, loved

Jews, everyone, children, family, uncles and aunts.

There once lived a shtetl that breathed with Yiddish life, possessing a thriving youth. Now, it is judenrein (free of Jews)…

My dream was that I would at some time travel home and see my family and friends, go to my mother's grave, and again walk the land on which once stood my cradle. But this dream was wiped away and extinguished.

But my memory of my hometown will never be erased as I still remember it from my early childhood.

I see for the hundredth time that frightening Friday night when my young mother was so suddenly ripped away from the world. Shortly after that the Novo-Radomsker Reb Ezekiel died. His son, Solomon Henik Rabinowicz, took over the Kise-Hakoved (God's throne) and a quiet and yearlong partnership with my father's stocking factory was interrupted.

The business began failing and my father believed, with complete faith, that

with the death of my mother and the departure of the Rabbi, Solomon Henik, that

for him prosperity was at an end. He constantly went around pensive, speaking

very little, and kept on calculating.

[Page 132]

Once he came home from Minkhah vaMaariv (afternoon and evening prayers) and said

four words which changed our whole life. He quietly, but firmly said:

“We're going to America.”

Although I was only 11 years old, I clearly understood that this meant a separation from family, from friends and from the hometown that at that time was so beloved and dear to me. We quietly began getting ready to get underway. We went down to Przedbórz, in order to say goodbye to my Aunt Dwoyrele and Uncle Zindl Tenenbaum who at that time were marrying off their oldest son Wigdor to the daughter of a rabbi, and from there continued the journey to America.

A day before I left Nowo-Radomsk, I woke up very early. I went out alone about the city, in order to take a quiet leave of the streets and little alleys, of the shops, of the trees and greenery, and of the people.

I went on Shul Street and, first of all, made for Aunt Chaia's and Uncle Yitzhak Ajzin's business, which was something of a mixed up store. On one side shelves were covered with cut-goods; on the other side lay food, sacks with beans, rice, sack flour, soap, kerosene and other foods. When I went into the shop that early morning, the store looked to me like the most glorious business in the whole world!

My aunt and my uncle lived with their thirteen children at Khananye Lewkowicz's's, where the choir was also located. But the [place] most loved to me was the long courtyard, which we children used for all kinds of games. We would dig out little holes, pour water into the sand and from that 'bake' different baked goods…

We would also plays with beans in the holes. Sukkous and Simchas Torah we played with nuts there. But the yard was the best for us for playing tag, for hiding, for jumping over wooden spools. The wooden spools were marked with white chalk on the black earth. We would spring over this on one foot and then we would have to say something.

Next door the majestic brick apartment house stood tall. In the evening the windows were lit and lighted the way for us. But this time when I came to say goodbye to the courtyard and to the apartment building, it looked through my child's eyes like a sort of enchanted castle that I thought I would never see again…

From there I followed the Shul Street to the mark (market). I went by the pump and spotted Welwele the water-carrier[1]. The children would called him by his nickname, teasing and shouting, “Welwe, you are a girl and not boy!” And he would [give an enraged] answer:

– I am a boy and not a girl…I am going to marry Tobele Mashkes and I will buy her a house with a seat… And we would all answer in a chorus:

– Go, go, you won't get married because you are a girl, a girl and not a boy.

But this time when I felt as if I would be seeing Welwel for the last time, suddenly he became beloved and dear to me. Instead of me teasing him, I nostalgically said:

– Do you know Wawe, I'm going away?

I put my hand in my pocket and wanted to give him a candy. He got frightened, thought I wanted to throw something at him, and he screamed:

– Fur in der erd arein. (Go in the devil.)

– I'm going to America, I said seriously, and gave him a caramel. He put down the water can, took the candy, studied me for a long time and said:

– Nu, go in good health and bring me the Meshiekh; I need him very badly…

I saw from afar Beilke the meshugena. She kept wrapping a pack of rags to [make them] look like a doll. She said that this was her child. Women would say that Bayla became crazy because she did not have any children. Usually, I would run after her together with a band of children, to tease her, pull her by the dress [and] call her 'Meshugane.' The louder she screamed, the more we would misbehave and tease the unfortunate one. But this time, the day before my departure for America, I suddenly felt great pity for her. I gave her a caramel. She was afraid to take it.

– Nu, take it, I begged her and at that I took off my kerchief and gave it to her.

She grabbed the kerchief wildly, wrapped her 'child' in it, looked at me with wild eyes, grabbed the caramel from my outstretched hand and ran away. At that she babbled something that I didn't understand.

I was left standing near Moshke's inn and with much nostalgia looked at the wooden building where the travelers and Hasidim, too, who would come to the Rabbi for Shabbos and yom-tovim, would stay. I noticed Tobele and we were very delighted with each other.

Women with fresh baked goods rushed home to their husbands and children. Jews with velvet tefilin bags went to daven. I looked after them for a long time, drawing each image into myself. Maybe, unknowingly, this was so that I would be able to write about it in my later years.

I had already in one way withdrawn from the Rabbi's court. In my ears I carried the Malamedishe murmurings of the teacher. A deep longing took hold of me and I wanted to cry.

From the Rabbi's court I contrived to let myself go to the 'new road' – later the promenade for Radomsk youth.

Suddenly I heard someone ask:

– Why is such a little girl so [deep in thought]?

I looked around and saw my father's friend, Michal Waksman. A little ashamed of my pensiveness, I quietly answered:

– We are going to America. It is a very far and long trip. I'm leaving everyone here. I won't see anyone again. I don't want to go. And I started crying.

– Nu, don't cry, Surale. He patted my back. America is a better

country than Poland for Jews.

[Page 133]

I looked at him and didn't absorb his words. We took leave of each other and I

went further.

I came to the edge of the river, looked at the water where we went erev Rosh Hashanah for tashlich. How pretty the river is, so peaceful and calm! Does a prettier river flow anywhere in the world? The shul was located not far [from there]. I stood and looked in and again admired the blue sky painted on the ceiling, with the stars, the small clouds and the flying angels. For the last time, I looked in at the women's shul and I let myself go to the 'new way,' Reymonta Way, where journeymen, dressmakers and bag makers would walk around after the Shabbos cholent and make romantic connections. The sun shone and warmed with its handfuls of golden rays.

That early morning was quiet and calm. The chestnut trees rustled. From somewhere a bird sang; a dog barked. I was back in the city. The city clock chimed eleven.

In the middle of the mark stood an organ grinder and around him stood a crowd of children. On his shoulders sat a monkey. He turned the wheel and the organ played a monotonous melody:

Red little cherries tear me [away],

And green let me stay.

Pretty girls take me,

And ugly ones let me go.

Oey! Woe is me!

And to my long life

We both trifled with love

A full three-quarters of a year.

Then he asked us to throw a groshen in the cup. And the monkey would pull out a little [piece of paper] on which our future would be told.

I threw in a groshen; the monkey gave me a rosy piece of paper and I read it:

– You will live long. You will receive a letter and you are going away on a long trip.

Very early in the morning, we climbed into a covered wagon that stood next to Moshke's inn. After that, as the wagon was already packed with passengers, the driver [put the whip to] the horses and said, 'Giddy-up, little horses, giddy-up.' They ran with a strong gallop along Shul Street to the Przedbórz Road. When we had already gone a considerable distance, Aunt Haia's [daughter] Eigl ran after us. She screamed and cried with such a lament, that the astonished driver stopped the covered wagon and asked her what she wanted.

– I want to say good-bye to the children; she pointed to me and to my sister. She had just learned at the last minute about our departure, so she came to say good-bye. She kissed us and then cried bitterly. As if she knew that she would never see us again…

Who at that time could know that this wonderful girl would die in a savage way in the Częstochowa ghetto together with her husband and seven sons, and never even be buried in a Jewish cemetery…

Translator's footnote

(A chapter [of] memories of the Jewish Self-Defense Organization in Radomsk)

by Zundl Grinspan

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

At the time of Shavous [in] 1906, on Shabbos before grinem Donershtik (Pentecost, which

comes fifty days after Easter), a group of friends walked around in the middle of the day on Neiem Veg.

Among us were: the two sons of Zemmah the shoemaker [who were] Bundists (a Jewish Socialist organization in Poland),

Tzivia, the pitsele's (small one), Feiwl, the leader of Po'alei Zion, Wilhelm, a member

of the Zionist-Socialist Worker's Party, the tailor's son Jakob, [a member of] Po'alei Zionist, Feldman

and others. As usual in those days, we were absorbed in a discussion

about Zionism, [the] Bund and the like. Suddenly we noticed a group of about

fifty Russians, who, it seems, came in on the train. This was suspicious to us

and we sent Moshe Judke the peddler, a Bundist, to find out what the comrades

were doing in Radomsk.

Moshe Judke was a tall young man and looked like a Russian. He went over to the comrades, greeted them with a cheery, Zdravstvuvyte in Russian and immediately became their friend. They chatted with each other and started to ask him how many Jews are there in the city. 'A lot' – Moshe Judke answered – And what do you intend to do here? – He asked them. After a short conversation they revealed [their] secret to him, that they simply wanted to slaughter the Jews.

He went with them up until Bugaj, where they held a consultation and worked out the plan for the pogrom. They asked Judke to send the anti-Semitic young men to help Judke immediately explained the whole situation to Eliezer Tanski (Bund), Dawid Kruze, Wolf Pitsele and Fiszlowicz (Po'alei Zion) and immediately called together a meeting on the Neiem Veg in front of the train. The three parties – Po'alei Zion, Bund and Zionist-Socialist Worker's Party. – immediately joined together and distributed arms among their friends. Each party had made a [constant] effort to provide arms – submachine guns, hunting rifles, daggers, etc. With the help of Social Democrats, the arms were smuggled from Germany in hay wagons through Mislowice, Sosnowice and Niwke.

That same Shabbos, at night, when the workers went home from the new furniture factory, 'Mazowie' the situation was explained to the pepesowtses (members of the Polish Socialist Party).

Polish [graduate students] marching with the rowdies was already observed between Minchah and Maariv (the afternoon and evening prayer services). We organized ourselves in a group together with the members of the Polish Socialist Party on Station Street, went out to the market and on Krakow Street, marching back up to the corner of Stzalkowske, and marched that way until it got dark.

The [graduate students] came from the market and into Stzalkowske Street. We came from opposite them from Krakow Street, into the market and invaded their group. A fight broke out immediately. They ran in the direction of Sthalkowske, but the members of the Polish Socialist Party stopped them near the hospital. There the real struggle first started. We broke the four night-lamps that lit the city and beat the rowdies in the dark corner [that was provided for us by the broken lamps]. They began screaming for help and later even used a bugle. After a short time fifty Cossacks came riding in from gendarmerie and then the members of the Polish Socialist Party disappeared with us.

The same week we knew that the rowdies planned to organize a pogrom after the ceremony for Pentecost. We informed the members of Polish Socialist Party from the Rakower factory in Częstochowa about that and asked them to come to help us. In fact, they came with weapons. We also got ourselves ready to ward off the attack and defend ourselves against the pogromists. In many houses we prepared vitriol (sulfuric acid) to pour over the rowdies.

We deployed groups in the flowing places:

After the ceremony we noticed that Cossacks had come with the chief of the city hall, Jashchetmski. The chief was a member of the Polish Socialist Party and helped the socialists a great deal. It turns out that he learned about the plans for the pogrom and the preparations of the self-defense organization and undertook appropriate measures in order disperse the peasant mob and avoid a blood bath.

That is how a pogrom was avoided in our city, thanks to the alertness of the

self-defense organization.

[Page 134]

by Leah Koniecpoler

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

My summer visits to Radomsk belong to my best childhood memories. As one [who

was a] resident of the nearby 'larger' city [of] Częstochowa, with its grey

houses and walls, I was drawn to neighboring Radomsk, with its prettier

neighborhoods. That is where my Uncle Solomon Konietspoler lived and I would

spend almost every summer there.

I still remember the empty fields of Zakszow and the Plawno pine forests. The taste of the milk remains with me still. And the bread [spread with] rosy preserves and butter, with which we would treat ourselves at Maier Gabriel's farm… Foremost are my memories of Radomsk's young people, as [being] heimishe, familiar and affectionate.

The great Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem's trip through Radomsk and our encounter with him takes an honored place among my memories of that time.

This was at the beginning of 1914. We knew that at 6:30 p.m., Sholem Alecheim would travel through the Radomsk train station on the Warsaw-Vienna express train. Reb Judea had made a strong impression on we young people [that] something [important was going to happen], an opportunity to see the great beloved Yiddish writer and perhaps even have time to speak to him!

At the hour we, a group of young people, gathered at the train station. We were all dressed up in our best clothes and awaited with impatience the arrival of the express train.

Suddenly a heavy rain began and the arriving train was visible in the distance. We sought protection under the small roof in order to stay out of the rain. But the roof was barely sufficient [as a cover] for all of us.

Then the rain became heavier and with it the train rolled in. [Someone] in one of the first wagons pointed out to us the wagon in which the writer [could be found]. Which rain? What rain? We ran to the designated wagon. The train had already started to go and in one of the wagon's window's [could be seen] the writer and his wife. He was wearing a white Russian rubashken (coarse shirt). He wore a pair of large glasses and, on his head, a wide Panama hat. Seeing us standing in the heavy rain and waving to him with our pocket handkerchiefs, he started smiling.

Taking off his wide hat, he began waving with it for as long as he could still see us.

Our good luck was indescribable. Water ran off of us. Our best clothes were

soaked, but it was worth it to me – we had the privilege of seeing Sholem

Aleichem and to be saluted by him.

[Page 135]

by Dovid Koniecpoler

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

I write these lines in the land of Israel in the year 1955 after going through

the saddest and most tragic chapter for our people. I think, what kind of an

impression can several homeless families in 1916 make on me after the Hilterist

inferno? But, obviously, we cannot let ourselves forget the time in which

Jewish Radomsk and her young people displayed so much humanity and willingness

to make sacrifices. These people had hearts that were filled with pride and

with a profound sadness for the Jewish, humane, Radomsker beauty that was so

ravaged.

A.

At the beginning of November 1914, the Russian military established a fighting position around Radomsk. Several Russian military formations marched through the city. From the start the Jewish population suffered badly. But later the war became routine and one became used to the war's concert of exploding shrapnel and shooting. At that time we did not yet know about any kind of aerial bombs or atom bombs.

There were rumors then about the bad condition of the Russian army which could not take care of all of its soldiers and that on the field of slaughter were many wounded, Jews among them, too.

Immediately, a group was established in Radomsk that became involved in the matter. They turned to the Kehile and to the Rescue Committee, with Mr. Fishel Dunski at its head. And when the Kehile and the Rescue Committee did not exhibit the proper initiative, our group, with H. Glikman, the dentist, at the head proceeded with the rescue work. We talked to Herszke Natan Rozencwajg, the owner of a horse and droshke, and in a few hours we were near the front.

After negotiating with the military organs, we immediately took several wounded Jews with us and drove them away to Mrs. Zaks' wedding hall. The arrival of the wounded excited the Jewish population. Jews brought straw; others brought bread and tea. Preparations were begun to prepare a warm lunch for them.

After providing the wounded with medical assistance, we drove back again to the front to bring more wounded. Austrians were found among the wounded Russian soldiers, and even today I still cannot forget the pleading looks of the poor Austrian wounded, asking that we not leave them on the field. After great effort we were successful and we received permission to take the Austrians with us. It turned out that one of them was a Jewish officer. I do not remember any longer how long our rescue action lasted, but it turned out that we saved a lot of wounded Jewish soldiers.

Combat in the area of Radomsk lasted six weeks. The last day of the retreat of the Russian military, a lot of Russian soldiers sneaked around in the city. The Russian military regime made it known that the death penalty would result for concealing any military personnel. Still, Jewish soldiers found a warm and quiet home with a lot of Jewish families.

From time to time a Jewish soldier from Odessa would come to our house. I remember his last visit with us. It was a Chanukah night. As usual, the soldier was very warmly received. My mother just then, as was the custom, oisgelost {rendered) the Passover schmaltz (fat) and the soldier sat with us and ate grevin (cracklings). The warmth of the room and the threat of danger showed on him; overcome and sitting at the table, tears ran from his eyes. My father comforted him and did not let him leave the house and he stayed with us for the night. Before going to sleep, he asked my father to wake him up early, so that he would be able to go to the Beis-Hamedrish to daven because he had a yahrzeit in the morning.

In the morning the Austrian army marched into the city. Among the captured Russian soldiers we found our Odesser.

B.

In the middle of winter, at the end of 1915 and the beginning of 1916 the Germans brought to Radomsk a part of the evacuated population from White Russia, among which were found a large number of Jewish families. They were provisionally quartered in the empty factory rooms of the “Thonet Brothers.”

We, a group of young people, leaders of Kultura, which was then still named the “Union of Youth,” set off immediately for the factory, in order to see how we could help.

What we found there caused our young hearts to shudder. In the corners of the factory were huddled the homeless families. Their faces expressed fear, despair and helplessness and such sorrow that tears rose in the eyes of some of us.

On the spot we decided that something had to be done here. I remember no meetings or budget discussions. But I remember very well the big round iron pot filled with food. I remember the pot being carried from the city into the factory and held on one side by Dovid Krojze and on the other side by Dovid Koniecpoler, Pinya Kalka and Leizer Bajgelman, Abraham Winter and Fishel Paris and other friends (who talked about giving money?). The organization was transformed into a big kitchen, where our gang, with Leitze Wilenska at the head, cooked.

Quieting the hunger of the unfortunate gave them a new feeling. The people began to feel that they are among Jews, and that they would\ not be lost. From the corners was heard the laughter of the young people and the high, joyful voices of children.

The relief activities lasted several weeks and during that time a strong

friendship developed between the homeless young people and us and there began

to take shape refined threads of affection between some of us and them…

[Page 136]

by Pinye Kalka

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Quite a few months had passed since the World War had begun. The Austrians who

captured our city were, in all respects, a lot more lenient than the Germans.

The population of the city lived together in a totally friendly manner with the

new ruler, both with the ordinary soldiers and with the military officers and

city-officials. The newspapers which we received would give us reports of the

daily news in their usual version with kleine exceptions of 'strategic'

train movements. We understood just what the words in the martial-language

meant, although all news was under a strict military censorship.

The economy and commercial life in the city more or less stabilized. The few pre-war industries were, of course, completely paralyzed; the big furniture factories and smaller factories were shut down. Then new war [occupations] developed such as [transporting] food or other goods from one city to the other. This was the main source for making a living for the average Jew, if not the Jewish population. Everything was sold and traded. The real name for it was smuggling.

But at that time in Radomsk, as in most cities in Poland, [there was the beginning of] boiling communal and cultural activity. The young people seemed to awaken from a long lethargic sleep, and with the whole hot Radomsk temperament threw themselves to a fresh source of life, which was named 'Culture.' The poorest classes as well as the rich, the tailors and the shoemakers as well as the intellectuals – all were ruled by the cultural trend.

The poor Jewish worker's street awoke and put on view their spokesman; they were: Dawid Konietspoler, a carpenter, Abraham Lipshitz, Leibl Gelbard, a true proletarian fighter, Leizer Bajgelman, Fiszel Gliksman, Brother Kroise, Brother Gold. Feiwl Ickowicz, etc.

The institution around which everyone gathered was the well-known 'Culture' with its library and reading room. Like hungry locusts, the young people invaded the library and the reading room every night and the books were carried out into the street as Radomsk was transformed into a university-city.

Rich cultural evenings with enlightened programs were arranged. Preparations for each cultural evening were made as for an important yom-tov. The leaders of the Warsaw Jewish bourgeoisie and workers' parties often came to agitate for their programs and ideas. The Mizrachi leader Herszl Farbsztajn, the Zionist-Socialist Worker's Party leader Dr. Josef Kruk, Pinye Bukshorn, the 'Bund' leader Vladimir Medem, the Po'alei Zionist Zrubol (the prince who stood at the head of the Jews who returned from Babylonia), Dua (D. Bogin) came. Every lecture raised a hot partisan temperature. The masses were drawn into the political debates. It happened that at the lecture by a Zionist speaker about Eretz-Izrael a tailor stood up and asked him, 'is there something new [you can tell us] concerning the Jews in Poland?' During a lecture by the Bund leader Vladimir Medem, a sarcastic Zionist man sprang up and demanded that the speaker not speak only of the bad, but of the good times of Zionism (a nice demand from naïve young man!). Medem answered him without thinking that he was leaving that for him and the proletariat audience from which to draw pleasure.

Under the [guidance] and leadership of the party centers in Warsaw and from the neighboring city of Częstochowa, organizations of the Jewish workers parties in Poland were formed in Radomsk. There arose the organization S.S. (Zionist-Socialist Worker's Party), later Fareinikte (United), which had succeeded in Częstochowa [and] occupied first place in Radomsk. After [the S.S.] came the 'Bund' and Po'alei Zion. [Together] with the professional unions, which were later created, 'United' and the 'Bund' directed the 'Union' and the 'Bund.' A 'consumers' cooperative' was created which was directed by the 'Union' and Po' Alei Zion. The most modern and prettiest worker's nursery was established on the Jewish street. Understand, that the Moshiach's time when all workers will live together in peace, was still far away and [their was considerable disagreement among the] parties. Meanwhile, the grand new epoch of the Russian Revolution began that revolutionized the working masses [all at once]. With [the revolution], even the occupation forces, even the 'loved' Austrians, couldn't be [considered] prefect.

But the war also endowed Radomsk with other events (which interrupted both the 'cultural idyll' and the struggles of the political parties).

A train arrived in Radomsk with the homeless from the war fronts in White

Russia and Lithuania. The homeless, mainly Jews with several of their Christian

neighbors, [traveled] by train for several weeks until they arrived in Radomsk.

The Radomsk young people (blessed they should be!), interrupted the party

struggle for a while, rolled up their sleeves and with customary Radomsk fire

and enthusiasm threw themselves into the work of giving the initial assistance

to the unfortunate Jewish war victims. Young strong hands carried the old

broken bodies of the refugees and dragged the bundles that they were able to

rescue with themselves from the devastation of war. A temporary home for them

was arranged in Kahn's[1]

factory. Immediately after groups were organized to

collect food, to find places to sleep and everything that the homeless needed.

[Page 137]

This was not a one-time job, but constant day to day

devotion [to] care and work that was also bound up with a difficult struggle

with the Austrian city officials. While it was possible to obtain warm food and

other necessities from the Jewish population, such luxuries as sugar and coal

had to be obtained through fighting [with] the Austrian 'rulers.' But

separately, this, too, was done, through the brilliant Fiszel Gliksman and

Leizer Bajgelman. Separately Fiszel Gliksman with his [sympathy for the

ordinary people] and humor encouraged and excited the mood of the battered

homeless.

The brotherly love and friendliness that Radomsk showed to the homeless [brought out] the warmest feeling for the city and her Jews. Fiszel and Leizer represented [the Radomsk Jews]. A lot of the homeless later left for America and here through their assistance and interest in Radomsk they showed their thankfulness to the old hometown.

Translator's footnote

by Berl Dudkewicz

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

The political situation was not very clear right after Poland's independence.

The left was at the center of power, but the executive power in the city square

was established on the far right. And all of the Rightist parties took

advantage of every opportunity to [instigate] political disturbances. Naturally

[they saw disturbances against] the Jews as the best opportunity of all and for

all times. And so it was on the 4th of March 1919, a Sunday,

that a large number of incited Poles gathered on the Neiem Veg (New Way).

And the blind and lame anti-Semite Witalski screamed that the Jews

were the only ones to blame because there was no bread. 'If we searched at the

Jewish bakers we would quickly find it.' The self-defense [organization of] the

Jewish workers' parties, was naturally, quickly informed and was prepared for

every contingency.

Abraham Dudkewicz was lifted up on the shoulders of the comrades and declared with such a sure voice, 'It is not true that the Jews are hiding the flour and bread. The truth is that the [authority in charge of food provisions] does not distribute enough flour, because it is in their interest that there should be disturbances, etc. etc.' Coming to the assistance of comrade Dudkewicz, the nearby starost [the governor of a Polish province] (by the way, he was called a Volkskommissar at that time) sent out the Pole Skomski. He endorsed the opinion of the Jews. And the P.P.S, a group on the left, immediately took over the masses and in the Jewish bakeries changed the [opinions of the masses and] some [of the] arrested political [prisoners] were released. And then the government official [in charge or] food provisions was removed.

By chance the leaders of the Jewish self-defense [organization], had already carried out an ambush of the former Austrian gendarme with the nickname 'Little Orange' a frightening anti-Semite and blackguard. Taking part then [were] the leaders of the self-defense [organization]: S. Wlaszcowski and the grober (fat) Herszl Surkewicz, Rubinsztajn, Konietspoler, Kube Wielunski, Henek Kalka, Leibil Goldberg, Srulke Altman, Abraham Szustak, Gotajner, Moshe Pzyrowski, Alek Plawner, Haim Szajlic, Abraham Aeile Dudkewicz, Motl Feldberg and others.

The telephone was disconnected earlier. Naturally, all of Radomsk's young Jews

were ready to stand against every attempt by the rightist elements or

pogromists. The reaction, however, did not silence these elements which then

still dominated the organs of power. A lot of arrests were carried out and

naturally among [those arrested] were some leaders of the self-defense

[organization], with A. Dudkewicz at the head.

|

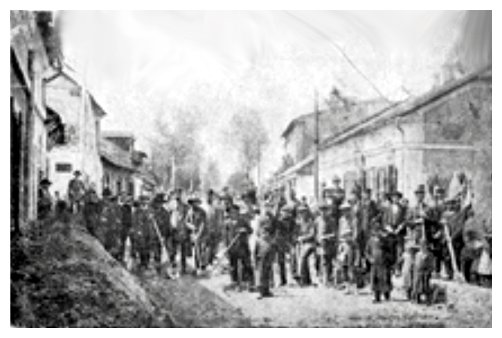

| An interesting card from 1915 |

This photograph-card was kept by relatives of the Misha (Moishe) Winter family,

which lived on Kalinske Street, No. 2 (in 1915). The photograph shows a group

of Radomsk Jews, who were captured by the Germans for compulsory-labor in

Widame. On the other side of the photograph, a son of Misha (Moishe) Winter

writes to his parents:

'… I was spared because I am sick on my feet, but I don't yet know what will be, if I will be freed… I worked very hard on Shabbos… We didn't want to work on Shabbos, [so] we received a beating… Tomorrow I am going to the doctor… No more news… I send only friendly greetings to you and the bride…'

This photograph was apparently [received] by chance. Added to the above

fractured information was: 'Please give [this] to Misha (Moishe) Winter,

Kalinske 2.'

[Page 138]

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

At the time of the First World War a German-Austro-Hungrian army detachment settled in Nowo-Radomsk. At [its entry] into the city, in 1914, a proclamation was issued to the Jewish population, by which [it was hoped sympathy and support would be generated]. The General staff leader Von Hindenberg and General Ludendorf, who after losing the war threw bile and dirt on the Jews and propagandized Hitlerist teaching, tried to give the lie to [the fact], that at the outbreak of the war, he had asked for help from the Polish Jews with servile words. In the archive of [the] Nowo-Radomsker 'Relief' [Committee] in America is found an original of the proclamation, which was at the time distributed in the thousands in the streets of Jewish shtetlech in Poland.

We produce here the original proclamation, with the same words and spelling system, in order to protect this document for coming generations.

|

|

|

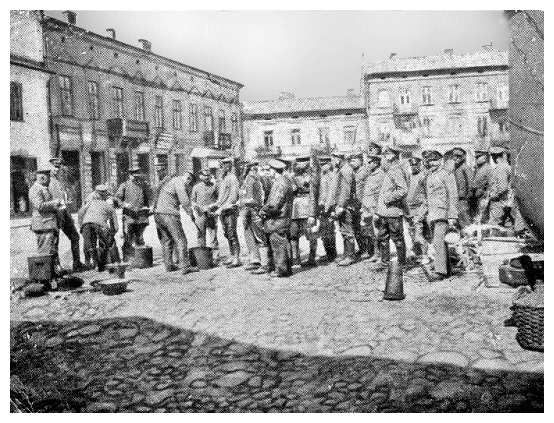

A squad of the German-Austrian Army (during the First World War)

receiving an allotment of food in the Marketplace in Radomsk. |

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

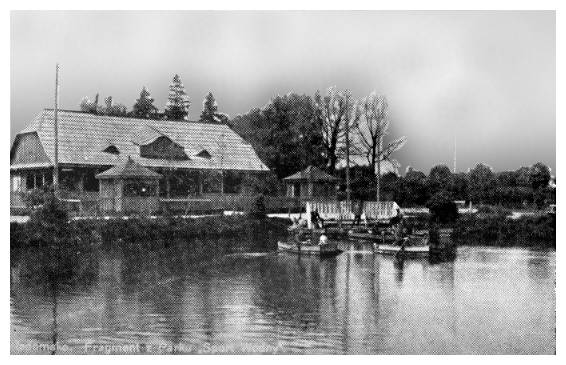

Radomsko, Poland

Radomsko, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 29 Jan 2026 by OR