|

|

|

|

[Page 294]

Yechezkel Boimstajn, Kibbutz Alonim

Translated by Pamela Russ

In memory of my perished father and mother, sisters and brothers, along with all the Jews of my town, I am writing my tragic memoirs. It is not simple to write these memoirs, particularly of such a gruesome era. But I wish to add my own memoirs to that which is now being written here in Israel.

There was a small town named Turobin, in the Lublin province, where every Jew had worries about earning a livelihood, worries about children, and fears of the tomorrow, and it still had to be good, because this was our destiny.

My parents had a bakery, in partnership with my father's brother. There was never any peace there. There were always arguments. One always had complaints of the other. They say that when there is no peace, there is no blessing. They argued for so long until they finally split. They made two bakeries from one. Each one considered himself to be on top of the other. Even if he was on the bottom, still he wanted to be on top…. They were enemies until each cursed even their father. When I turned twelve, I had to help in the bakery. When I got older, I had to go work elsewhere. This was in the year 1937: I left my mother and father, young sisters and brothers. My heart ached. I worked for a year and amassed some money, then went back home and gave my earnings over to my parents. I resumed working in my father's bakery. But this did not go on for long, because the war broke out; Germany invaded Poland. The war did not last long. Even before the Germans invaded our town, I decided not to stay there because we heard and knew that when the Germans would come it would not be good. I decided to go to Russia. I went over to my father when he was standing and praying. This was Hoshana Raba [during the days of Sukkot] in the morning. He was wearing his talis [prayer shawl]. I told him that in my opinion it was better for me to go to Russia. My father said that he did not want to go to the Communists and also told me not to go. Afterward, when I went to say goodbye to him, he said that he was sure he would never see me again. I said my goodbyes to everyone and left.

And now new challenges began. Alone, without any family, I roamed with other refugees. We came to Lemberg, and it was black before my eyes. There was nowhere to stay, even for one night. There was nowhere to buy any food. In this way, we wandered

[Page 295]

for some time until I found out that the Russians were registering people to go to Donbass in the mines. You had to enlist to work for two years in the mines. There was no other choice. The Russians took our Polish documents and the following day we arrived in the train station. We had to be ready by ten in the morning. As we were standing and waiting at the station, and a commander arrived with a list in his hands, and began to call out names. For each name he called out, that person had to go into a car [of the train]. In this way, all the wagons filled up. The doors were locked, and we did not see anything at all during the entire time the train was moving.

When we arrived in Dobnass it was already dark, but here everything was prepared. We were divided into blocks of fifteen men. It looked like barracks because there were only men there. It was already cold but it was much better than in Lemberg. Here we had food and a place to sleep. They gave us a few weeks of rest after which they told us that we would go and become familiar with the work. They gave us work clothing and when they let us down into the mines it became dark in front of our eyes. They took us to the mines for three days and divided us into work groups. The labor was very difficult and also life–threatening. Almost every day one of our Jews became a victim. Some stopped going out to work because their energies were depleted. Some started to try to escape. Everywhere there were fewer and fewer men for work. When I looked around the barrack, I saw that more and more beds were empty and so I went over to the supervisor of the mines and in the name of all the others I asked him to use us according to our physical abilities because were no longer able to work in the mines. He said that there were no factories for us here [in which to work]. We asked him to let us go, and once again he did not consent. He told us that we had to work for two years and after that he would free us from the work in the mines. But we did not wait for him to free us and we started to free ourselves. We simply ran into the nearby small towns. I ran with a friend of mine to Satzi; it was not very cold there; the surroundings were nice and the city was pleasant for us. We went to enlist so that we were able to work but we were declined first because we did not have any Russian papers, and second, they noticed that we were deserters because we did not have any documents to show.

[Page 296]

The Turkish border was close by and there was also a port (Namal) not far away. The police ordered us to leave the city within twenty–four hours or we would be arrested. When we heard that, we returned to Meinkop. In that city they let us get work, but we had to report to the police once a month. This lasted for a half a year until finally we received Russian passports. I left Meinkop and went to Krasnodar and my friend stayed there. He worked as a shoemaker and once again I began to work in a bakery.

But this did not last long. The Germans invaded Russia. I could not figure out what to do with myself because the Russians ensured that the Germans would not come here. I remained working in Krasnodar.

One beautiful bright day when I came home from work, I received a notice that I had to appear for military service. I went and reported. There I found a good many people. It did not take long and they took us to the cargo station where the cargo wagons were already prepared for us.

When the train began to move, we had absolutely no idea where they were taking us. But when the train stopped, we asked the conductors where we were and they told us that we were behind Kiev and that the Germans were shooting to the other side of Kiev. When we got out of the wagons there was no one left to ask because the commissioners had fled like mice. The Germans continuously bombed Kiev. Masses of people fled from there, and I was also among the fugitives. Everyone wanted to save themselves from death. The Russians wanted to give us over to the Germans. We knew that we were not considered military because among us there were also undesirable people. Running like that, I do not know how after a month's time I came back to Krasnodar. By that time, the Germans were already behind Rostov. I went to present myself before the commissioner, but as soon as he saw me, he asked how did I get back, then ripped out the gun from his belt and shouted at me: “I am going to shoot you, Jew! You don't want to fight in the war!” I stood like that before him shaking with fear. I told him that everyone in our train had fled, and that included all the commissioners. He continued to scream and I thought he would kill me any second. But he finally understood that I was not the only one who had fled. He knew that the commissioners had committed sabotage and he became a little gentler towards me and gave me permission to go work in the same place. But it did not last long.

[Page 297]

In a short time, once again we were summoned to the military. And then they chased us on foot out of Krasnodar to Rostov because there were no trains going there.

We travelled at night, because the Germans were bombing all day. And so we came to Bataysk, ten kilometers from Rostov. There was nowhere else to go because the Germans were everywhere. We wandered around the area of Rostov. Suddenly, in the middle of the night, we were ordered out and told to march, where to – we did not know. But one thing was clear: wherever we would go, we would fall into the hands of the Germans. But orders are orders. It was a cold, snowy night, and we heard that not far from here were Germans. We arrived in a village where all the houses were empty. There were no people. Here, they told us that we should form into a unit. We knew that something here was false. They told us to lie on the bare earth, but we could not sleep because of the cold. We huddled together and it was a little warmer. Everyone began to snore. I hardly slept that night. But from time to time, I napped for a few minutes and trembled with fear. In my dreams, my father and mother came to me and said: “Do not be afraid, everything will be fine.” And that is how it was.

Soon it began to dawn. Those who were asleep barely awoke themselves, and soon there was an order that we had to evacuate the village because the German tanks were approaching. Everyone fled as quickly as possible. I came to Rostov and began thinking about how I was going to rescue myself.

I went into a courtyard, but I did not know if there were any Jews there. I spent the entire night there. I went into a wooden hut and slept there all night. When daylight began, I left because I could no longer tolerate the cold. I left the hut even before it was light and I did not know where to go until I saw a ray of light through the splits of shutters. I went over to the house and knocked on the door. They told me to come in. When I entered the house, I saw they were packing up their things. They asked me if I was Jewish, so I began to speak Yiddish to them. They told me that they hoped I would stay with them, and then told me to go to the train station. There were masses of people already there, mostly Jews. I remained close to the Jewish family and together with them we went to Kavkas [Caucasus]. We arrived not far from Tiflis [Tbilisi] and went to a village. There they sent us to work. I said that I was a baker, so they sent me

[Page 298]

to work in a bakery. After I had worked there for an entire year, they gave me a new passport. I understood from this that I was now able to leave so I went to Tiflis [Tbilisi]. I worked there until the end of the war.

It was now 1945. When I heard about this on the radio I began to think about going back to my home in Poland. But how could one go to Poland? I began to take the trouble and consider this. I prepared all the legal papers for traveling until Lemberg. I did not want to wait longer so I caught a train and arrived in Lemberg unencumbered, as someone freed from the war. You were not able to travel further, you had to wait until the Jewish committee would organize all of it. I had to wait a whole month until there was a train to Lublin. When we arrived in the Lublin station, we got out of the cars [of the train] we heard the Poles talking amongst themselves: “Where are these Jews coming from? Hitler said that he killed all the Jews.” When I heard this I was very frightened and since I had nowhere to go I only went where my eyes led me, thinking about how I would get to the town of Turobin, and that maybe I would find someone there from my family. Nobody could have imagined such terrible destruction. As I was walking around, I came to a market where people from the area were gathering together. One person from my town, a Christian, recognized me. He came over to me and began to interrogate me asking where I had been during the time of the war. I also asked him about my town Turobin.

The Christian told me that the Germans had murdered all the Jews in Turobin and he convinced me to go into the town with him. I agreed. Just as I was going to go with this Christian into my town, an angel came to save my life. This was a woman from my town, by the name of Khana Bazilis. The woman grabbed my hand and dragged me down from the wagon where I was just about to leave with the Christian. The woman began to tell me what had happened to her and how she was the only one left alive because a Christian that knew her had hidden her. So I went with her to her place and then she told me that I was lucky that she had arrived just as the Christian was trying to trick me to go to Turobin, because they would have killed me there.

Two Turobin Jews, Josef Kopf and Motel Fuks, met their death that way when they came to the town in order to get the things from their homes that they had hidden before they fled from there. For one week we sat there and cried for all those who had been killed. After that, she remembered that an uncle of mine from Bulgaria was alive, but she had no idea where he was at this time.

[Page 299]

She told me to stay with her until my uncle would come because whenever he came to Lublin, he usually came to her house. I obeyed and slept and ate in her home, because I really had nowhere else to go. In a few days, my uncle appeared. But when he came into the house, I did not recognize him: He was dressed completely differently. I knew him from before when he used to dress as a chassid, but he did recognize me. We embraced each other, kissed each other, and cried terribly about the great tragedy that had happened to us. When we released each other, with tears in his eyes he told me how he and his son had saved themselves and how his wife and all his other children were found by the German murderers in a stable of horses where they were hiding.

We stayed in the town overnight, eating and sleeping at her home. The following morning, we left her, and my uncle and I went to Bitam (in German: Beiten). Before the war this was a German city but after the war this city belonged to Poland. Here, my uncle managed to get a few rooms right after the war and here I stayed alone for a few weeks because my uncle and his son would travel around for trade. When I saw that my uncle had left me alone and did not leave me any money, and I had nothing to eat, I found a community where they took me in. When my uncle came back home and did not find me, he found out from the neighbors where I had gone. When my uncle found me and asked why I had left, I said to him, understandably, that I had no choice. By that time there were already a few settlements in the Lublin area. In a short time they sent me over to Sosnowica. I stayed there until the whole settlement left Poland and went to Israel.

Meanwhile, my uncle came to visit me in the settlement and of course I welcomed him very nicely, better than he welcomed me when he took me into his home. At that time, he offered that I go with him to America, but I naturally declined because I was afraid to travel again. He parted from me upset, and he went on his way. Meanwhile, I stayed and worked in the bakery of a Christian until I had to leave the city with the Aliya [group immigrating to Israel] and they I no longer went to work. They made me get drunk so that when the baker would come and call me to go work, I would not be aware of it. They would tell him that I could not go to work because I was drunk. When my boss came and called me, unfortunately, he left with a bad impression of me and of Jewish workers in general.

[Page 300]

In about a few days' time, we were ready to go to Israel. We were told not to take any heavy bags with us because we would have to pass through several borders on foot. Since we did not have much to take with us, we were able to follow this order. The next night we came to the Czech border. There was a small town there, it was called Krinitz [Hranice]. We had to wait here for several weeks before we could “shwartzen” [sneak out at night]. Soon, in the middle of one night, they awoke us to get moving. We did not have to wait long, we were all prepared. We went into a forest until light began to dawn, and by then we were in Czechoslovakia. Everyone's heart beat in fear. The entire way, we were not allowed to breathe loudly. We were not allowed to hear a sound from anyone. That is how we crossed the first border from Poland to Czechoslovakia. It was not a simple thing to steal across a border in those times and in those places. Meanwhile we stayed there for a few weeks until we had to move on.

The second border was from Czechoslovakia to Austria. Once again, we took to the road at night. We crawled across the mountains and in the forests in the dark where you could not even see the stars in the sky, that's how dense the forests were. When we came to the Alps, it was extremely difficult to climb. We had to go on all fours, until we arrived, midday, in an Austrian village. We rested there for a few hours until cars arrived and took us to Vienna. They took us into a house where people were already waiting. The house was Rothschild's hospital. We remained in Vienna for a few months, until we were able to continue onward. This border was already easier to cross. Only the first two were difficult to cross – from Poland to Czechoslovakia, and the German–Austrian border. Now we crossed into Germany. They sent us into a camp by the name of Lopreis. Here we also found many Jews who had come before us. We remained in this camp for half a year, until we had to cross the Italian border. This was also a difficult border to cross, because we had to protect ourselves from the British. Once again, we traveled all night, and early in the morning we arrived in small village in Italy. They hid us there until dark. Then cars came and took us to Milan. Here they took us into a vocation school that was called Codvarela School. From there they took us to Rome. There they took us to a Caesar's villa in an Italian village that was called Grotta Ferrata. Here we also remained for half a year. While we remained in each of these places for a long time, we studied Hebrew.

[Page 301]

From some individuals, we already heard that we would be going directly to Israel. That is why they kept us far from a port, so that the British would not suspect that we wanted to sneak away to Israel. In that village, our directors assembled a lot of people, and they had to take us in secret, because there were English spies that moved around there, and they guarded all the ships. We had to leave there also at night. They took us from the camp to the seashore. From a distance, we saw a ship weaving in the waves, but we still did not know how we would get to that ship.

But our directors had already prepared everything beforehand. We were taken to the ship in small rubber boats, then one side of the rubber boat was tied to the large ship, and from the other side they pulled a rope to the seashore. That's how we were pulled to the ship, and there was a ladder already set there for us. That's how we climbed onto the ship. There was no other way because there was no port there. They filled up the ship as they pack up a barrel with herring. The crowding on the ship was so dense that since there was no room for each person to stand on his feet, you had to lie down. This was an old cargo ship. They packed in about 1,500 refugees until the middle of the night, and when the ship began to move, we felt as if we were wavering just as small children feel when they are being rocked inside. The heat inside the ship was so terrible that we could not stand it. So people went on deck to get some air. When we were already a distance from the shore and the waves began to hurl at the ship from all sides, we began to vomit. Those who lay on top, vomited onto those who lay underneath. You cannot describe the agonies of these inhuman conditions in which we had to live on the ship. It was an illegal journey in all regards.

When we were already fifty kilometers from Haifa something happened to the ship. Water began to flood into the mechanical part of the ship. The ship stopped floating. Now there was no choice but to call the British for help. Soon airplanes appeared and very quickly two large ships appeared alongside our ship. They began to pump out the water from the rooms of our ship and our ship straightened itself out on the surface of the sea. Some of the British who had boarded our ship began to ask where we were going. Understandably, everyone answered that we were headed to Israel. They laughed at us and said: “Your ship will not be able to go there,” and they disembarked from our ship. They were summoned again, and they came to us and told us to get onto their ship. So the elderly and the pregnant women boarded

[Page 302]

the other ship. They were taken to Cyprus. Then, through a loudspeaker, we were once again asked what we wanted. We answered that we wanted to go to Israel on our ship. So they tied up our ship with ropes on either side to two of their ships, and we hung up our blue–and–white flag. And that is how we arrived in the Haifa port. Then they ordered us to board their ships so that they could take us to Cyprus. Of course, we did not want to do so. A fight broke out. Whatever fight we had left in us, they received over their heads. But it did not help. We battered them; this was our thanks to them for saving us from drowning. I remember that I threw a package of butter into the face of one of them and he started to lick his face with his tongue. But nothing helped. They were stronger than us. With force, they carried us over to their ships and took us over to Cyprus into a detention camp.

This took place on the eve of Passover 1947. Here in the camp, we also went through terrible experiences: We slept in tents, and we suffered from thirst because they did not give us enough water to drink. When some of us began to demonstrate, and we approached the gates, the British began to shoot at us. Soon, two of our people were killed. The others fled, nothing helped. We remained in that camp the entire summer, and after that we were taken into a winter camp where there were no tents, only tin huts which we could not go into during the summer because the tin was scalding hot. But it was freezing cold there in the winter. This is how we suffered for all of two years, because we wanted to go to Israel. They considered us to be the worst criminals.

In 1948, when the United Nations declared Israel as a state, the British freed us from the camp, and ships came from the State of Israel and began to take us over there. I arrived in the Land of Israel only in January 1949. From the ship they took us to Beit Leyad. Here everyone had to pass through a military commission who selected those who would have to go immediately into military service. Those who were freed were taken to Beit Olim in Pardes Chana. From there we were sent to Ma'aborot [where there were refugee and absorption camps] because they wanted to make sure we had somewhere to sleep. They took us into a place where there were beds and mattresses, but there was still nothing with which to cover ourselves. The supervisors said we had come too late, and there was no one to talk to.

[Page 303]

This was after four years of wandering. I saw what was going on here. I collected my few rags and left to one of my cousins. He welcomed me warmly. He too was a new Oleh [immigrant to Israel]. After, he told me to go to Haifa. There was a Beit Olim [residence for new immigrants] in Bat Galim. But you needed to have connections to be permitted entry. It was very difficult for me to get this, but they did let me in. Shortly after that, I began to think: “How is this going to work? I have to find a job. But I am a baker!” I went to a bakery and asked for a job. They sent me to the Histadrut [General Organization of Workers in Israel]. I went to the Histadrut and the secretary of the bakers said that he did not believe that I was a baker. So he sent me to a bakery for an examination. He gave me a note. I did not know what he had written there. I could not read Hebrew. I worked in that bakery for an hour and they sent me back to the secretary with a note saying that I was a baker. He started asking me where I lived, whether I had a family, and of course, I answered that I had just come from Cyprus, and that I had no one, and for now I was living in Bat Galim. So the secretary said to me that he could give me work for a day or two but he really had to take care of those who with a family and children. He said I must come twice a week to register, and each time he sent me to another bakery. I asked him, did he not think that a single person needed to earn money to survive? He answered that there was nothing he could do to help.

Life became terrible for me. I thought it was very important for me to come to my own country after such a war, but even here I was suffering. I thought that for now I would stay in the Beit Olim and after a day's work, I would go there and rest. But they did not allow me to do that. The Beit Olim was in a large barrack of British people. The house was crowded, and not all the residences would get together at the same time. Some left to work, and meanwhile others arrived. It was impossible to rest there after work. Now it was different. Many new Olim were arriving. They were being brought to Israel on cargo ships, and here in Israel, they were being provided with everything: money, work, and with housing. That is how it is in this world: One person cries and another is successful. For me, it was not good at that time. I saw there was no other way out, other than to get married. But how could I allow myself to do this? I had no money, no place to live, I could not even get any work. But I actually did get married, with the help of my uncle. Then my wife gave birth to a girl, and I gave her a name after my dear mother, Raizel. Then came another daughter, and

[Page 304]

my uncle who was just in Israel at that time for a pleasure trip, asked me to give the name after his mother Serel. This was my mother's mother. I looked around at that time and saw that it was not good to live here with two children because the walls were peeling. This was an old Arab house – so I left to Kibbutz Alonim. I am living here now for ten years. My young daughters have since grown up and they are studying well along with the other children of the kibbutz. I am working here in my vocation, in a bakery. Here in the kibbutz there are other families from my hometown Turobin.

To close my memoirs, I want to wish that our children have a happier future than we had, that they honor all those who died, whose names should never be forgotten.

Tzivia (Einvohner) Blutman

Translated by Pamela Russ

On Friday, September 18, 1939, in the afternoon, the Germans marched into Turobin. They came through the Lublin road. The town was filled with homeless people who had fled the Germans, beginning in the Posen area – Kalisz – Lodz. Many had hoped to find their secure place of refuge in this burdened town of Turobin. Everyone hid in cellars and other places in fear, and waited in terror and anguish for the cruel fate that awaited them.

One day passed, and then another in calmness, and we did not feel the [presence of the] Germans. They did not bother us. A week passed like that. As life goes, people began crawling out of their hiding places and everyone went to do his work – some to business, some to their own vocation. People began to believe that the treatment by the Germans was not as terrible as the homeless had related, and that it was so–called gruesome propaganda.

One fine morning, we saw groups of tens of Gestapo men coming from the direction of the municipality. These men went from house to house snatching up girls for work that required them to wash the main road to Turobin with rags and buckets of water. The torture began. They poured buckets of water onto those who were thought not to be working quickly enough. They also beat [the girls] mercilessly. This is how the daily work went until the winter, when the snow began to fall. They also snatched up people to peel potatoes for

[Page 305]

the military. At the beginning of the winter, they also took men for work, regardless of age. They were led into the forests around Turobin to chop wood and to clean the snow off the roads around Turobin. At the beginning of the year 1940, a group of Gestapo men came to Shmelke Drimler with an order to create a Judenrat [Jewish Council] that would be responsible to carry out all orders that they would receive for the Jews in Turobin.

Meanwhile, many more refugees from the surrounding cities arrived. These were people whom the Germans had chased out from their living places. They were placed in the Batei Midrashim [Study Halls], synagogues, and even in the large synagogue, because all the houses were already overcrowded with the homeless who had come earlier. The objectives of the Judenrat, among others, were:

1. Shmelke; 2. Baumfeld Avrohom; 3. Zweken Avrohom; 4. Kuper Yekhiel; 5. Halperin Berl; 6. Shneider Shulem (Shabtai Golan); 7. Frumer Tuviah.

The departments of the Judenrat were as follows:

The committee to provide Jews for forced labor was comprised of: Berl Halperin, Schulem Schneider, Tuviah Frumer; and the committee to take care of the refugees was comprised of: Shmelke Drimler, Yechiel Kuper, Avrohom Zwekman. They hired police to keep order in the town, comprising of: Hillel Leder, Mottel Jakobson, Yitzkhok Bernstajn, Yakov Frumer, Shmuel Roizner, Avrohom Feder, and a few of the refugees. The goal of the police was to capture people and put them into forced labor; to search out bunkers where people could be hiding to avoid being sent into forced labor, and so on.

During this time, a typhus epidemic broke out among the refugees as a result of poor nutrition and lack of medical help. Daily, 15–20 people died. The help that was provided by the American Red Cross from Switzerland through American Jewry somehow secretly disappeared. Only little bits reached the refugees. As the epidemic began to take over the town, the Judenrat took drastic measures. They created an isolation point for the sick in the Beis Medrash [Study Hall]. This was under the supervision of the city paramedic Leizer Shtreicher, and a women's committee assisted him: Miriam Zweken, Khana Bezis, Henye Hersh–Leyb's, Tzivia Zimmerman, Rokhel Fuks, Frimtche Milkhman, Tzipe Miriam Moishe's, and so on.

As soon as the typhus epidemic broke out, the Germans closed off all the roads to Turobin

[Page 306]

and secured each road into and out of the city. They severely punished those who did not follow these orders. Disregarding the regulations that ruled with hunger, some Jews – among them Shimon Glass, Hersh Jakobson, and so on – risked their lives and smuggled in flour and other life necessities into the town, and in that way somewhat appeased the hunger which, along with the typhus epidemic, reigned over the Jews in Turobin.

The First Evacuation

One Thursday, in the month of May, 1941, between three and four in the afternoon, a group of SS men tore into the secured ghetto, under the direction of SS men Bauer, Shindler, Riger. They grabbed up people in the streets and took them into Pinye Gewurtz' store, and into Velvel Liberboim's store, and into Yitzchok Goldberg's home, and saying that it is a shame to waste a bullet on a Jew, the SS men threw grenades into the above–mentioned places. In that way, with terrible anguish, more than 100 Jews were killed. Among them were: Soroh Dvoire Lender, Shaindel Braverman, her mother Golde Reva Braverman, Khantche Drimler, Perele Drimler, Mottel Shenker, Shaindel Tzukerman, Khume Kraitman. As they ended their bestial work, the Nazis ordered wagons to be brought, and under their watch and escorted with beatings, they placed the bodies, which were so beaten up that they were beyond recognition, onto the wagons and took them to the cemetery and buried them in a mass grave.

At the first evacuation, I, along with a large group of Jews, was sent to Krasnystov the following morning. We arrived in Krasnystov in the evening, exhausted and drained. We were detained in a water field, and that is how we spent the entire night – in water and in the cold. In the morning, we were set out in rows, and then ordered to march in the direction of the train station. When we arrived there, each of us received a piece of bit of bread and some black coffee from the Krasnystover Jewish police. Soon a rumor began to circulate that we were not being taken to work but that they would make soap out of us. From whom and from where we heard this news, I do not know until today. Very soon, I decided to save myself, that means to run away, and soon there came a good opportunity for this. A group of Christian women passed close by to us. They had come from the village to Krasnystov to go to church. Soon, unnoticed, I joined the group, went along with them, and when we approached the church I quickly turned away from them and went back in the direction of Turobin. A farmer's wagon was coming up this road.

[Page 307]

The farmer, from the village Kozienici near Krasnystov, stopped and asked me where I was going. I answered him that I was just discharged. He believed me because I looked like an Aryan, and he took me into his wagon.

Aryeh Goldfarb

Translated by Pamela Russ

A. The Tragic Murder of Arohom Peltz and His Wife Necha

When they were in the Sobibor camp, Avrohom Peltz and his wife Necha were among those who organized the uprising of the camp. He himself murdered two SS guards with a simple pair of scissors, and he was able to flee from the camp with his wife. They hid in the forests for a long time until they were able to come to the village of Wierszewina. In that village, the farmers surrounded the two [husband and wife] and cruelly murdered them.

B. Yakov Feder, may his memory be blessed

When Yakov was in the camp Majdanek, Yakov told an SS man that there was a lot of money and foreign cash hidden in his house in Turobin, and he was prepared to show the SS men the hidden place on the condition that he was to be freed from the camp. The SS men accepted this, and they drove to Turobin. He showed him the place and they actually did find the entire fortune there. They took it all and then immediately returned Yakov Feder to Majdanek, where they murdered him.

Yerachmiel Fogel

Translated by Pamela Russ

In Memory of My Murdered Family

I am relating my brief memories which I am writing here – printed for the holy Yizkor Book of the Turobiner community, with the intention to perpetuate the memory of my family and my town for the children's children, and for generations. They should know about the most bestial deaths which were used by Hitlerism on our parents, brothers, and sisters.

I was born in Turobin in the year 1922 to my parents Shmuel and Dvoire Fogel, of blessed memory. My father Shmuel, may he rest in peace, was a tailor. Many respectable people

[Page 308]

did their tailoring with him, and many knew him as an honest and decent person. He had a beautiful face, with a long wide beard, and followed the mitzvos [Torah commandments] religiously. He prayed every day and was very pious. My mother Dvoire, of blessed memory, wore a wig and was very religious. They ran a religious Jewish, refined home, and had a peaceful life. My mother gave birth to six children, but five remained: three sisters and two brothers. But now, with great sadness, I am the only orphan remaining.

I remember when I went to cheder [early religious school] and later to the Polish school, I heard more than once anti–Semitic remarks from the Polish students. When I was older, I joined Beitar [Zionist Movement]. After that, my friend Yisroel Aberweiss convinced me to join Hechalutz [Youth Movement trained in agriculture in preparation for immigration to Israel]. I remember well the expressions of the Chaverim [“comrades”] at the time, that “our only future is in the Land of Israel.”

On the eve of the outbreak of World War Two, in the year 1938, my father, of blessed memory, died, and I was left an orphan, at not even 16 years old. The entire responsibility of supporting the family rested on me. It is easy to understand how difficult it was for me then.

The war broke out in the year 1939. Hitler's fascist army shot and bombed, and in just a few days, marched into Poland. They grabbed people for work, beat them, and murdered them. My mother cried and worried all the time about what would happen to her children. One morning, we saw the Red Army marching into Turobin. Happy faces appeared, but this lasted only a few days. It was Simchas Torah [last day of Sukos holiday]. They said that whoever wanted, should go with them to Russia because they were leaving us and they did not encourage the Jews to remain with the Germans. I decided to go along with the Red Army. The time was short, so much so that I did not have time to say goodbye to my family. When I was already in the military car, my youngest sister Necha'le brought me a piece of the cake that my mother had baked for Simchas Torah. From a distance, I saw my mother, brothers, sisters, all waving to me. At that time, I thought this was temporary, and that in a short time I would see my family. To my great sadness, that was the last time I saw them.

In the year 1941, when I was in Russia, Hitler's army invaded Russia. They moved forward, and the Russians receded. Bitter reports were heard, that just as the Hitlerists captured a town, the first victims were the Jews. I began to worry about the fate of my family.

In the year 1944, we heard that Hitler's army was beaten, and on a certain

[Page 309]

day, I heard on the radio that the city of Lublin was liberated by the Red Army. At that time I was in Bataysk, in the region of Gruzye. At that time, communication was very difficult. You also had to have permission to travel, but I took a chance and went from town to town on the roofs of trains. I traveled like that for two weeks, until I arrived in Lublin just for Kol Nidrei [Yom Kippur prayers]. In Lublin, I found Jews from the Polish military, and in the Peretz–House [shelter for refugees] I found Jews who had saved themselves. Then I found out that from my big family, there was not even one survivor. I also heard that several Jews who had saved themselves, were murdered by the Polish bandits.

After these bad reports, I decided that I would no longer stay on these soiled Polish grounds that were drenched with Jewish blood. I went back to Russia, the war was still going on. But the end of the Nazis was already close.

In the year 1945, I was in Moscow, and heard that Hitler's downfall had come. I decided to marry and start a new branch of the family.

In the year 1957, I decided to go to Israel. For that goal, I first went to Poland. When I was in Poland, I decided that I wanted to visit the town of Turobin. I remember that when I was on the bus with my cousin, the Poles looked at us contemptuously, and as we passed the cities of Piaski, Krasnystov, Wysokie, all were Judenrein [cleansed of Jews]. When I arrived in Turobin, a shudder overtook me. Not one Jewish soul, the houses destroyed. I asked a Christian, where is the courthouse? He asked me if I had come to sell my house. I recognized the house where I had been born and knocked at the door. “Please come in,” someone answered. I entered and saw that there were Poles living there. So I left to the municipality to get my birth certificate. On the way, I noticed, and my cousin noticed that suspicious Poles were following us. Suddenly, a Christian approached and said that we had better leave the city quickly because they were getting ready for us, and as a “friend” he suggested that we “leave” [run away quickly]. The Christian helped us get onto a bus, but the thugs wanted to break into the vehicle. Miraculously, we were able to escape. When we arrived in Lublin, the preparations did not take long, and my family and I soon left for Israel.

Dov Zuntag

Translated by Pamela Russ

Without a doubt, many people remember Reb Mendel from our town, Reb Mendel Szmarak, an Orthodox, modest, refined Jew, with his majestic beard and his thick, overgrown eyebrows, through which his eyes looked with difficulty. In his home – they looked high up, and when he was outside – they humbly looked down on the ground.

He always used his free time to study a page of Gemara with great affection. On Shabbat, after the cholent [hot meat and potato stew served on Shabbat], he always sat in his designated place in the Beis Medrash

|

|

|

|

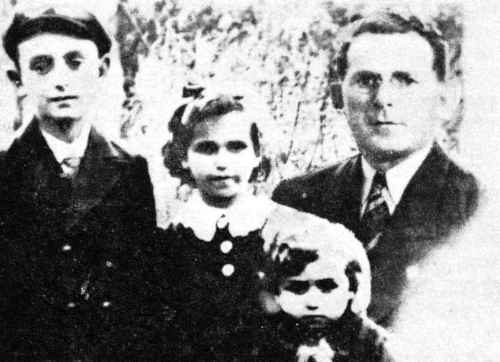

| Mendel Szmarak, Shprintze, daughter, son, and the children |

[Page 311]

and studied. If someone had taken his seat before him, he did not make a big deal of that; he found his own corner where he would be able to do his holy work. In contrast, there were other scholars who were egotistic with “glorious ancestry” and they [the scholars] demanded their own place even if others had come before and their seats had no numbers. Mendel did not belong to that category.

His wife was called Shprintze, of blessed memory. This woman was a Cossak Jewish woman. She took it upon herself to support the family just as other women of her sort did, those who wanted to be a “footstool” to their husbands in the next world. She used to go to the village, do trade with the farmers and especially on market days, when that was the day, she took a sack of products over her shoulders and when she found it necessary, she shouted out to whichever farmer. Of her own husband, she said that he was an idler.

It is understandable that this sort of Eishes Chayil [woman of valor] took care of the family and this also meant that the husband had the distinct opportunity to continue his religious studies.

This is how the family Szmarak lived calmly and quietly, not wealthy but comfortable. The one thing that created disturbance and serious worries for them was that in their elderly years they still had a daughter who needed to be married. Their daughter Fradel was already not such a young girl according to the criteria of the times: When a girl was already over twenty, she was no longer considered a young girl, and Fradel belonged to this category of an older girl. One has to be careful to note that when a girl of these years was still in a refined home this was a great tragedy and a source of constant pain. The religious Jews, however, believed that a destined spouse comes from heaven and if God has no mercy and does not send the match, maybe that daughter was judged to be passed by. In such a situation, you had to take every opportunity to make a match, no matter what.

In these situations the custom was that when a sort of girl such as Fradel did not find her mate and her parents were financially comfortable, generally “money is the answer to everything,” and they would already find an appropriate young man. But since Reb Mendel was not a rich man, it was actually difficult to find a match. To find just any mate does not even enter anyone's thought and there was a great conflict between two serious choices: either this daughter would heaven forbid, remain single, or she would have to be displaced from the great tree of ancestry and marry into a family that was a little beneath her. Only Elijah the Prophet

[Page 312]

was able to discard the hierarchy of the ancestry and measure this by the pound and by the gram. To this day, it is impossible to explain how certain people maintain an index of each individual family, how great their ancestry extends, actually according to every period and comma.

And for these very reasons a potential mate for Fradel was not so quick to happen. However, Reb Mendel successfully found a wonderful spouse for his son Chaim, of blessed memory, and for his daughter Menucha, he found a wonderful son in law, Reb Yakov Fogel, may he live long. And why should we not continue the tradition?

The women who occupied themselves with making matches were not professional. They did this more so for the sake of God rather than for the sake of making matches. Usually, these women, on a regular Shabbat day or on a holiday would visit one side of the potential in–laws and soon the secrets of the discrete dealings of the match would be carried across the entire town. If the event would end in a fortunate outcome then this would be carried out with a large dowry and then they would write up a contract, and from the time of drawing up the contact until the wedding would take a bit of time. This “bit of time” had no boundaries. To do this quickly meant about half a year. It could also have taken a year or two. The reason for these conditions depended on the speed in which the bride's side was able to prepare her dowry and the outfitting [all other home necessities], and sometimes tragically, the match was dissolved, and the bride and groom had to forgive one another (for the terrible shame that they had caused the other person).

Since we know how a match was done, the matchmakers and their assistants took themselves to Shprintze, Reb Mendel's, and they presented a potential groom for their daughter Fradel. The potential groom was Avrohom Frumer, Reb Yosef Frumer's son. Even though the ancestry of Reb Yosef Frumer was not as great as that of Reb Mendel Szmarak's (as we know it was weighed by grams), but because the bride did not have a wonderful dowry, and the groom Avrohom had his own workshop and assistance, and he also earned a good living, Shprintze said that if her Mendel would say amen, then the match would go through. Despite the fact that Shprintze wore the pants in the family and was the wage earner, in these decisions Reb Mendel had the final word. And Reb Mendel agreed with his wife and his daughter Fradel. He did this because he was a good man and he saw their impatience. Therefore, he gave his blessings of amen and good fortune.

In truth, Fradel and Avrohom already knew each other from the Tarbut [Hebrew culture center] library. They used to meet there. But Heaven forbid that either of the in–laws should know about this because the institution of the Tarbut was “totally non–kosher,” and every father denied that his child visited such a place.

[Page 313]

And so there was an engagement and then a wedding, and then grandchildren were born.

This couple was happy and Reb Mendel and his wife Shprintze had even more joy and more pride. As was his habit, Reb Mendel would go to the Beis Medrash every day. His house was at the edge of town and the Beis Medrash was located at the opposite end. His mechutan [son–in–law's father] Yoske, did not live far from the Beis Medrash where the young couple also settled. It was as if it had been written in Heaven that where Reb Mendel passes every day, that is where his daughter would live. Reb Mendel had to pass through the entire marketplace until he reached the Beis Medrash. As we know, Reb Mendel did not lift his eyes off the ground [in modesty], but when he passed the home of his daughter, he intentionally lifted his head and looked. Who were his eyes looking for? Obviously he desired to look at his grandchildren to embrace them and to say with his lips “these are my offspring” and these are His “holy ones” and “future generation” but, “man thinks and God laughs.” Hitler's slaughter arrived and he took all the best.

May their memories be blessed!

Translated by Pamela Russ

Khone Blutman, son of Sone and Faige, born in the year 1918. After the death of his father, he was raised by Yitzkhok and Faige Treger. Because of the difficult economic situation in the home, in his younger years he had to work as a shoemaker's associate for Sholem Shabtai, and help the elders with his income. In spite of his hard work, he was full of energy and a lust for life, loved by all his friends and acquaintances.

As a youth, he joined the Bund party [Jewish labor/socialist party] where he actively worked, and by nature he was gifted, and he successfully took part in the Turobiner dramatic circle.

When the war broke out, he and other Turobiner fled to Russia and he settled in the town of Boguslov, near Kiev, and there he met his future wife Zhenny Lukow and he also established himself there with his skills in the local drama circle. At the outbreak of the war between Russia and the Nazis he voluntarily enlisted in the army, and in the bloody battles at the main station of Voronezh, he died a heroic death in 1941. His memory remains deep in the hearts of his surviving brothers and all his acquaintances.

Avrohom Treger – Born in Turobin in the year 1919. With the outbreak of the war, he fled to Russia with the Red Army's retreating train

[Page 314]

from the Lublin district. He settled in the town of Ortov, near Vinytza (in Ukraine). In that town he got married and set up a family.

With the outbreak of the Russian–German war, he voluntarily enlisted in the Red Army to fight against Hitler's military. He died as a hero in the slaughter of Rostov in the year 1941.

|

|

|||

| From right to left: Khone Blutman, Avrohom Treger with his child | ||||

Translated by Meir Bulman

| Żółkiewka | Expulsion to Izbica, 5 Cheshvan, 5703. |

| Goraj | Expulsion to Bełżec, 8 Elul, 5703. |

| Turobin | Expulsion to Izbica, 20 Tishrei – 20 Cheshvan, 5703. |

| Janów Lubelski | Transfer to Zaklików, 20 Tishrei – 20 Cheshvan, 5703. |

[Page 315]

| Józefów | Final [?]liquidation 20 Iyar 5702 Expulsion to Bełżec, 22 Cheshvan, 5703 Ghetto Liquidated Spring 1942 |

| Modliborzyce | Expulsion to Krasnik 20 Tishrei – 20 Cheshvan, 5703. |

| Krasnobród | Aktion, 19 Elul 5702 – 20 Cheshvan 5703. Local murders (Judenrein) 15 Cheshvan, 5703. |

| Krasnystaw | Expulsion to Izbica, 22 Iyar 5702, 20 Tishrei – 20 Cheshvan, 5703. |

| Krasnik |

Final liquidation 21 Cheshvan – 21 Kislev 5702.

|

| Rejowiec | Final Aktion, Tishrei – Cheshvan 1, 5703 and Elul 5703 |

|

|

Top row: Peretz Fink, Shlomo Ziss Melekh [?], Yosef Yegerman, Avraham Fuks Second row: Abish Blitman, Yosef Kopf, Yisrael Zeidel, Chana Givertz, Hillel Ledder, Gitel Tzitrenbom, Yakov Mitzner, Yakov Gutwiling, Hersh Biterman. Children of Yakov Gutwiling (Avituv) |

[Page 316]

|

|

Top standing from right: Eliezer Zimerman, Berel Zimerman, Yenta his wife, Yitzkhok Zimerman, Dovid Zimerman Seated from right: Mikhoel, Alte his wife, Moishe Zimerman, Khaya his wife, Eidel his daughter, Arish his son, and Shloime his grandson [Note: The two women in the picture seated next to each other – Alte and Khaya – may be reversed, since the daughter Eidel looks younger than wife Alte, so the note in the caption may be in error.] |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Turobin, Poland

Turobin, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 17 Oct 2017 by JH