|

|

|

[Page 271]

|

|

|

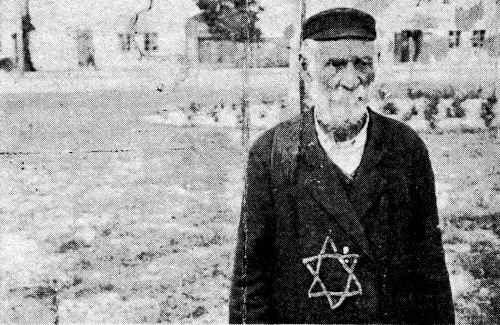

| These pictures were found among the ruins of the city, after the destruction |

Itte Fass (Zweken)

Translated by Pamela Russ

The owner of the memories was born (1921) and raised in Turobin. She went through the tragic experiences of the Jews of the town, beginning on September 1, 1939, when the Nazi invasion of Poland reached Turobin, and the Nazis' brutal behavior towards the Jews began

[Page 272]

to be noticeable. Miraculously, she was fortunate enough to save herself – jumping off a marked, running train, and after all kinds of roaming and inhuman suffering she managed to survive. She arrived in Israel and set up a home in Jerusalem, near the very border of Ever HaYarden [Transjordan, the other side of the Jordan].

Her descriptions are filled with exact details, chronological memories of the expulsions and destruction of the entire Jewish population of the town.

|

|

| This picture was found among the ruins of the city, after the destruction |

1.9.1939

Very early, airplanes appeared on the Turobin horizon. We thought that these were Polish planes doing manoeuvers, but tragically, by midday, it was evident that these were German airplanes, and that by 5 AM, Germany and Poland were already at war. This is how our tragedy began. Already in the second day of the outbreak of war, many Turobiner Jews already ran away from the town to the surrounding villages. At the same time, the town became filled with Jewish refugees who had fled from the cities and towns that bordered Germany. Among the refugees were all kinds – the rich and the poor. The wealthier

[Page 273]

came by car, others by wagon or on horseback, and then many on foot. It was so pitiful to see these people's pain. Many of them were exhausted and then stayed with us in town, waiting until the Germans would take over the town, and then they would be able to return to their homes. We also noticed a great tumult in the Polish army. They were marching (retreating) without end. On September 18, 1939, after some small fighting, the German murderers marched into town. They were there for a few days, and soon there came a report that Russia and Germany had divided Poland into two parts: until the Vistula it belonged to Russia, and beyond that – in the west – to Germany. There was great joy, and in the first days of Sukkos 1939, the Red Army marched in. I remember how Reva Briliant knocked at the door and happily called out that we should come out into the street. Volvish Vassertreger [water carrier] was carrying a gun, as well as Chaim Treger and others whose names I no longer remember. The Jews breathed in relief, and raised up their heads a little. But sadly, not for long. A few days later, our Polish neighbors put out a rumor that the Red Army was leaving, and the Germans were coming back to replace them. A confirmation of this came quickly from the Zhilkevker military command, that the Russians were moving in only until the Bug River. The youth began fleeing from the city in the direction of the other side of the Bug River. Not all of them were able to decide whether or not to leave their home. The elderly who were so closely tied to their small piece of land from their great–grandparents could not come to terms with this fate of voluntarily leaving the town.

I remember a fact: On Simchas Torah [last day of Sukkos holiday], Aizik Oberweiss, of blessed memory, was just leaving the synagogue after prayers and he was holding his talis [prayer shawl] in his hand. Towards him came riding a Russian Jewish officer. The officer stopped the Jew and asked: “What sort of valuables do you have?” So Aizik took him to his home. The officer burst out laughing and told Aizik to leave the house and run away.

There were also many people who fled to Russia and then came back. For example: Motel Diamant and some other bochurim [young men] went to Michałowo, but seeing that there was no place better than one's own home, he returned. Then the Turobiner Christians fabricated a story that on the way he had shot some Polish officers. Motel remained in hiding in a Jewish home from 1939, because the Christians wanted to take their revenge.

The terrible winter of 1949 arrived. The cold was fierce. They began to capture people for work. What kind of work could there have been in a town like Turobin? They snatched up elderly Jews and ordered them

[Page 274]

to carry rocks from one place to another. This was only a ploy to denigrate the Jew; to mock him in the neighborhood of our Polish friends… At that time, Turobin had a population of 8,000–9,000 residents. Jews from nearby towns that had been burned down came to Turobin – towns such as Frampol, Janów, Biłgoraj. There were also evacuated Jews who came to us, from Łódź, Kalisz, Kutno, and other cities. They gave the people half an hour to leave their homes and 20 marks for each person, and then sent them out to the General Government. We too had the merit of taking in some unfortunate people. The town became very crowded. Every family had to take in one or two people. People were also quartered in former Jewish stores. All Jewish stores were locked up, and the Batei Midrashim [Study Halls] were overcrowded with refugees. A typhus epidemic broke out from the overcrowding and hunger. There were houses where all the people were sick and there was no one to take care of them. There was no doctor to be had. Jews were not permitted to be taken care of by a Christian doctor. At the demand of the local Christians, they sent us a Jewish doctor by the name of Hendler from Kraków. He also put up a hospital in the Polish school. They organized courses for the nurses, but the Angel of Death still took his portion. There were about 40 deaths a day. The frost was so bad that we could not dig into the ground deeply enough to bury the bodies. The fear of illness was so great that people were afraid to cross the street so as not to be in contact with other people. But the Gestapo did very little about this. They stole everything they could from the Jews.

One afternoon, Gestapo men from Lublin arrived. There was no Judenrat [Jewish Council] yet, so they went to the Council Head Pik and demanded a list of the rich Jews. He treated them well, and answered that in such a small town there were no rich Jews. Then they demanded a list of community representatives. He gave the list of names to them, and soon thereafter they invaded the home of my parents. They separated the women into one room and men into another, and then they began their beatings, demanding that they be given money. They cut off the men's beards along with some flesh. They did this in a few houses. Then they invaded the town's synagogue, broke the lamp and the Holy Ark; they took out the seforim [religious books] and burned them, ordering the Jews to dance. After that, naturally with more beatings, they asked: “Where is your God?” This type of incident happened many times.

In this atmosphere, months passed. Then the order came that all Jews, without exception of type, 12 years and older, had to wear armbands on

[Page 275]

on their right arms, 12 centimeters wide, with a Star of David sewn on. Jews were also not allowed to be outside except from 7 am to 7 pm. At the same time, the Council Chief Pik received notice that he no longer was in charge of the Jewish population. He must select 10 appropriate Jews who belonged to the Jewish community before the war and were also active socially in Jewish life. So he chose ten men, who were:

In spite of all these difficulties, there were Turobiner residents who risked their lives and smuggled merchandise, traded whatever was possible, and with that became wealthy. The majority of them ended up in prison, but the refugees ended up the worst. They were also the first to be sent away to the camps because they had nowhere to hide.

In January 1940, the Germans sent an order to the Judenrat that by the end of three days the Jews had to pay a tax, a very large sum of money, and if not, all the Jews would be evacuated. There was a great commotion, and no one believed that there was such a large sum of money in Turobin. The Judenrat went to the Landrat [civilian official] in Krasnystaw. He deducted only a few tokens from the sum, 50%, and somehow they escaped the Angel of Death. At about the beginning of 1940, another order came once again to the Judenrat that they must appoint their own policemen. These too were not selected of their own will. The names of the policemen were:

For all kinds of reasons there was a great hatred between the Turobiner Jews and those newly arrived. First, because the Turobiner were better situated

[Page 276]

and those newcomers were always the ones who were needy. The jealousy, more than once, led to fights and informing. The people became very demoralized. This was also an enemy of the Judenrat because they lent money, they sent them to work, they were the messengers for everything bad.

Months passed like that with hopes for a better situation. One hope everyone had, was that they would outlive them. The Jewish children were not allowed to go to school. They were neglected by their own parents because there simply was nothing for them. You could see how the children played in the Gestapo, how one child treated another if he was a “Jew.” A few young girls got together at the home of Zeldele Zilberklang, and there, in secret, they taught children to read and write. The girls were: 1) Rivka Zilberklang, 2) Rivka Veisbroit, 3) Etel Zwekin, 4) Rikel Eidelman, 5) Malka Fuks, and two Kalisz girls.

It was the holiday of Shavous, 1940. The city of Zamość needed 500 men in a labor camp. There was a tumult in town. No one wanted to go voluntarily. The Judenrat collected gifts and went to Zamość. They negotiated down to 200 men and they drew up a list of young men, age 18 and over. There were those who “bought” people for money to go instead of their son. Shmelke Drimler, Bunim Mayerson, Avrohom Boimfeld, Dovid Bernstajn, Shloime Akerman, and others, got people to go instead of their sons going. The youth suffered greatly there. They worked for many months and were starving and beaten at the same time. Twice a week they received food from the Judenrat and received beatings at the same time, and also risked their lives by delivering the food supplies of the Gestapo–gendarmerie.

Months passed in hunger and need, and spring 1941 came with the outbreak of the German–Russian war. The repression of the Germans towards the Jews increased. It was forbidden to eat white bread, meat, and so on. They could also not leave the town, that meant [go only] until the bridge, from one side until the garden and the other until the suburb. They shot Bashele Kopenboim at the bridge. It was evening, and they saw a taxi coming with Gestapo men. Four men got out and began shooting the people in the street. After that, they likely decided that a bullet is a luxury for a Jew so they collected about 30 Jews, herded them into the house of Velvel Liberboim, threw in a few hand grenades, and that's how they went from house to house and killed 112 people, among them young children and elderly. They slaughtered without mercy, anything that came into their hands. The following day they collected the blood and flesh, because …

[Page 277]

the bodies were not recognizable, and they made two communal graves. Some weeks later, an order was given that the Jews should remove the tombstones of their families and put them together in the Jewish cemetery. Soon the Councilman Pik arrived and with trucks, drove the tombstones to several places. He paved the road from his home to the municipality with Jewish tombstones. His friend Fliss paved the road from his home to the mill, and they also paved the roads with Jewish tombstones. The Germans asked in mockery: “Where is your God?” That's how the residents became more dejected. They felt that this was not yet the worst thing they had experienced.

One Friday night, screaming was heard: “Open up, Jews!” Whoever did not have a place to hide was taken into cars. Some were taken to Bełżec where later the gas chambers were built. And some were taken to a sugar factory near Szczebrzeszyn. Then they took only men. The second Shabbath morning, the Gestapo–gendarmerie and the city Wehrmacht [armed forced] arrived and they also wanted men in the same sugar factory. But they did not find too many men. This Judenrat also hid itself, because if the Germans caught a Judenrat member they forced him to search out Jews along with them. Then they decided to take women as well. I too was among those taken for work. They took us to the railroad station and told us to wait there. If they would bring men from Wisoki, then they would let us go free. Making a mockery of us came to an end. Late in the night, when the Wisoki Jews arrived they let us go home, naturally being beaten en route.

The people who were taken to Bełżec suffered very much. They also had to be brought food. This was very risky because they shot more than one person who came close to the camp. Nevertheless, every two weeks the Judenrat chose two people of these ten and they were regularly brought food and clothing.

Day in and day out, in fear of the future, with beatings and starvation, the summer of 1941 passed. We Jews saw our terrible fate in front of our eyes. Winter 1941 arrived. And at that same time, an order from the German authorities that all Jews must give in their fur coats and fur collars and everything that is made of fur. Anyone who did not obey this order would be punished by death. Anyone they spoke to said that they would rather burn the furs rather than give them up. But life was too dear than to lose it over fur, so within three days there was not a piece of fur owned by any of the Jews, as a piece of pig with a religious Jew. You saw people carrying coats and collars

[Page 278]

made of stiff linen. They also carried summer coats, and then they had nothing to wear, but they were happy now that the murderers had to become dependent on Jewish fur.

News came at the beginning of the year 1942, that Turobin must be evacuated. Only craftsmen [physical laborers] would be allowed to remain in Turobin. We did not yet know at that time that evacuation meant death, but we were told that all the people would be going to the Poleszczi forest. It was the Council Chief Pik who carried out the evacuation with the “assistance” of the Judenrat. There was chaos in town. Who wanted to leave Turobin? Turobin had a few hundred craftsmen, but primarily Turobin had small merchants. In such a situation, how can a small merchant become a glazier or a shoemaker? But it happened anyway. For money, the Council Chief Pik turned a merchant into a laborer. Lists were compiled, and according to the lists, you had to stay in Turobin. You sold your last things in order to remain on the list, but this also came to naught. The Germans did not stick to the list, it was only an excuse to squeeze out more money from the Jews. Rumors came from other cities that people were being snatched up in the streets. They were being taken away by train and no one knew where they were going. This happened in Krasnystaw and in Izbica, because there were train stations there. Every Jew began to build bunkers for his whole family because they knew that Turobin would not be an exception, and that is exactly what happened.

On July 17, 1942, the first evacuation took place. After the evacuation, everyone came out of the bunkers. They still did not know that evacuation meant death. How the evacuation took place, I sadly cannot describe because I myself was in hiding. But one thing I can say, that the noises of the shooting during the evacuation carried into the deepest cellars as from a horrible slaughter. The largest number of Jews who were evacuated were from the refugees who lived in the Batei Midrashim [Study Halls], former Jewish stores, and they had nowhere to build the hideouts for themselves and for their families. During the evacuation, they also shot some people, and since our Polish neighbors informed on us, the destruction increased. On that very same day, Christians from the city and from the village already moved into the Jewish homes. Jewish seforim [religious books], and all kinds of Jewish items, besomim [spices] boxes [to use as part of the blessing at the close of Shabbat], from which our parents took a sniff at each havdalah [blessing at the end of Shabbat], candelabra, prayer shawls – you could sell all that for a few pennies. But who needed all these kinds of things at that time? The rest of the Jews lived in terror. They felt that the worst was coming closer. They thanked God that

[Page 279]

the Germans were accepting the gifts from the Jews. And what tumult it was. People were asking the Judenrat to take money from them, when a year earlier these very people did not want to give them any money. They shivered from each movement and every loud cry. People became simply discouraged, and this was the worst. No one cried anymore and no one reacted when terrible things happened.

This is how the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur arrived in 1942. There were rumors that the Judenrein plan [cleaning out the Jews] was to be enacted in some cities and towns. The German newspaper “Der Velkischer Be'abachter” [“The National Watch”] reported that the Judenrein action was approaching from the Lublin district, but no one could imagine that such a thing could happen. It was the first Friday after Sukkos, and very early a taxi arrived with Gestapo men. They stopped at Motel Shenker's building. His tavern was owned by a Volksdeutche [an ethnic German]. From there they summoned the whole Judenrat and the Polish municipal citizens. They took some addresses from former wealthy Jews. When all of these were already in the community center, they did not allow anyone out of there, except for Yechiel Kuper, so that he would bring them some things. I myself was the runner to get all kinds of things, because not everyone wanted to obey the Judenrat. And also that time, Yechiel Kuper came to me that I should get him leather for women's boots, two suits, soap, coffee, and a nice diamond ring. I bought all of these and when I gave these things to Yechiel I…

[One line missing in original Yiddish]

they will likely leave immediately. It did not take long, and we saw Yechiel leaving with Feigele Boimfeld and Yitzchok Yaffe in a taxi on the side of Olszanka. A half an hour later the taxi returned without the people. That is how, slowly, they took 14 Jews out to the Olszanker forest and shot them there. The only one who wanted to run away was Shimon Boimfeld. But the Polish police captured him and as a punishment they held him until three o'clock and locked him in chains in the community center. When they took him out, with a raised head he called out in Polish to the Polish policeman and to the Germans, in German: “You'll never get all the Jews out, and then the revenge will be tremendous!” They beat him and threw him into the taxi. They took him on the same route as the other 13 Jews. There was a tumult in town, and by the time everyone gathered their thoughts about what had happened news came from the Zhulkiewer Judenrat that until the next day at 8 AM – this was Shabbat morning – no Jew was allowed to remain in Turobin. Looting of our neighbors began immediately. Naturally, this did not get to the point of beatings. We were helpless. They beat Chaim Meyer

[Page 280]

Lieberboim, and other Jews who worked with leather, so that they were not in any condition to go with the transport in the morning. Before dawn, they prepared wagons for baggage, children, and the elderly, and all the Jews had to go to Izbica.

That's how, on October 14, 1942, we left our town of Turobin forever. We traveled all of Shabbath accompanied by a heavy rain. We arrived in Izbica in the evening. My father, may he rest in peace, was from Izbica, so we had a place to hide. We went directly to that family. In Izbica there were Jews from all the surrounding areas of Turobin – Żółkiewka, Gorzków, Wysokie, Zamość, Tomaszów. Izbica became a Jewish city, meaning that from there, there were daily transports to Bełżec and Sobibór.

Then came a notice in the morning that anyone who could pay a certain amount of money could remain behind. The sum was very high and not everyone had that amount. There were also no more places to hide because each Jew had built his own mouse hole for his own family, and Monday, very early on, they began to snatch up people and everyone was assembled at the train station. Those whose names were on the list went to the right, and the rest were sent to the left and then sentenced to death. There was chaos. Everyone pushed his way to the right. Then they encircled everyone and packed everyone into the wagons. The Izbica Jews call this day “Black Monday.” Also, 90% of our holy Turobiner were also taken out to Bełżec at that time. This was the first Monday after Shabbos Bereshis [first Shabbath after Sukkos, beginning of a new Jewish year], October 16, 1942.

In this manner, my place of birth, Turobin, was destroyed, and along with the city, my dearest ones. The only survivors of those who suffered Hitler's hell am I, Chana Pulk, Tzivia'le Einvoiner, Hilel Leder, and Moishe Roizner.

Now, about my experiences of October 16, 1942, until the end of the war.

As I already related, we had a large family in Izbica. When we came there on the tragic Shabbath night, we divided up our family. I and two of my sisters stayed with one uncle, my parents and my youngest sister – with another uncle, and my grandfather and grandmother – with their family, because my grandmother also came from Izbica. We all hid in cellar holes. We heard shooting all day. Overhead, where we were hiding, was a tavern, and we heard the laughter of the Christians. There were about 50 people in this cellar.

[Page 281]

We could not sit because it was very low, and it was very wet. Izbica rested on swamps. That's how we sat until people came and said that the wagons were already sealed, and they already saw people, that is Jews, outside. I went up to see what was happening with my parents. Then I saw my mother wounded, and crying, she told me that the head of the Judenrat of Izbica arrived, and he was a neighbour of my grandfather in Izbica, and he said that an order had been given that whoever had paid and was on the list, and if they called his name and he was not here in this place, then he would not have the right to live in Izbica after that. Everyone believed them, even though each time their bluffery was obvious. That's how my father took my mother and my youngest sister and they went to the train station. My mother's head was split open with a truncheon, and the women who were standing near her protected her so that she would not be shot. She likely fainted because when she revived, the train with the transport had already left. The ones on the list had also left. That transport that left had 10,000 Jews. There was no more place in town, there were no more people lying in the streets. But everyone knew that those who had remained would have the same fate.

There were men who fled into the forests and there the Poles captured them and turned them in to the Gestapo, or they themselves killed the fugitives. A cousin of mine made a deal with an Izbica Christian who worked in the Izbica magistrate, to get documents in Polish names. And my mother, may she rest in peace, bought these for me and my sister Etche, may she rest in peace, and they were supposed to bring these papers to us. But they could not do this, unfortunately, because on Shabbath night [Saturday night] the evacuation of Judenrein began. Once again we were separated from my mother and youngest sister. They were at the home of one uncle, and I along with my older sister and the middle one – were at the home of another uncle. Also, my grandmother and grandfather were hidden somewhere else. We went down without any food, without any water. And that is how we sat until Wednesday afternoon. When they took us out, we could not even stand on our own feet. They beat us fiercely and took us to the theater where thousands of people were dying of thirst. They put us outside around the theater with guards all around – firemen, Polish policemen, German gendarmerie, and Gestapo. There was also my aunt's sister with us, she was from Zamość and she already had a Polish identification. She bribed a Polish fireman, so that he should get her out

[Page 282]

along with me. She did not know Izbica, she was from Zamość. I too was not so familiar with the surrounding areas of Izbica.

One of the guards approached me and gave me a bucket, and also gave one to the girl from Zamość, that we should go bring water for the Jews at the theater. I take the bucket, and on the way the girl says to me that she had bribed the Christian and that he would let us escape. I was opposed to doing this because I did not have any Polish documents. Everyone knew me, because I was black, filthy, and had not eaten since Shabbath. This was already Wednesday night. The Christian understood that I was opposed to this and he began to beat me. He was afraid that I would inform on him that he had taken a bribe. So he took us out of the city. We traveled all night. In the morning we heard shooting. We met a Christian woman on the road and asked her where we were. She said that this was Izbica. It was miraculous that we actually came to a village that was three kilometers from Izbica. There, we went into a house where there was an elderly woman, a stranger to us. She gave us some means to wash up a little and some food. The Zamośćer girl said to me that I should not call her Gutche any longer, but Irena, then she gave me her passport into my hand so that I should learn the details written on her passport, that is the names of her mother and father, and so on. As I was holding the documents, I saw a transport through the window. Among those in the transport I saw my sisters and a few other familiar people from my city. I threw aside the documents and ran to my sisters. She also saw her parents and ran to them. On the way she told me that she forgot her passport at the home of the Christian. The transport went to Trawniki for work. That is what they were assured was to happen.

We came to Trawniki in the evening and they took us to the camp. But the camp director did not want to accept us because he said there was no room for us. Immediately, they began herding us to the train station. Jews began grabbing up their money, and whoever still had some jewellery had to give that up. Ukrainians began to chase us into the wagons, ordering us to give them everything because within an hour, we would not exist anymore. They crowded more than one hundred of us into a wagon. People stepped on the elderly and on little children. We had no air. Everyone pushed to the door, to the small sliding door, to get a little air. When the train was standing still, everyone said they would jump off. But when the train began to move no one wanted to jump because the Germans knew that people jumped from moving trains, so the arranged for trains in which

[Page 283]

the Germans rode as well. One railroad car for the Jews, one for the Germans. The conditions in the car were horrific. The screams went up to the seventh heaven, and no one tried to jump because they were shot immediately as soon as the Germans detected the slightest movement near the small window that was there. I said that I would be the first one, and discussed it with my two sisters, telling them that they should jump too. My two cousins said they would jump too. There were men there who had items with them that could be used to open the window. They lifted me up, I threw over my feet, and held onto the window with my hands. The Germans began to shoot. Then, for the last time, I heard my sister's words: “They shot her.”

But they did not get me. I pushed myself off the train with my feet and remained lying on the ground not far from the opening [of the train], as if in shock. But it did not take long and soon I came to my senses. I was still able to see the train at a distance. I had discussed that whoever would be the second person to jump should stay in his place. I will get to him by using the tracks. I wandered around all night and then found my cousin, no one else. He reassured me that both my sisters had also jumped train, but I never found anyone else.

We decided to go to Chelm because my cousin had an aunt there. He wanted to dress and go join the partisans. When he jumped he could not get through with this coat, so he had to leave it behind. I decided that I would buy a Polish passport and papers there. We jumped not far from Wojsławice and continued on foot to Chelm. Not far from Chelm, a Christian warned us not to continue because in Chelm they were amassing all the Jews and putting them into the church, and from there they were being taken to be gassed. We remained still like stone and decided to go back to the Christian near Izbica where the Zamość girl had left her papers with her birth certificate. My cousin was supposed to go to Izbica and get some clothing from one of the Christians she knew. We went for eight days without food or drink. We did not have any strength left to lift even one leg. We went with the Polish route, and the second Shabbath at night, we came to the Christian. There I found the document that the girl had left behind. I could not take the passport because it had the picture of the girl. I only took the birth certificate and parted from my cousin. He returned to Izbica.

He found my mother there and my oldest sister. She had

[Page 284]

also jumped from the train and wounded her head somewhat as she jumped, and she returned to Izbica. It was my uncle who told me all this, he survived the war. A few days later, they took my mother and my oldest and youngest sister, and my cousin who had also jumped from the train, and other members of my father's family. They had to dig ditches for themselves. They were then shot in the Izbica graveyard. There were 400 Jews.

From Wólka Orłowska I went on foot to Krasnystaw. There I was afraid that Christians from Turobin would find me. I went to the train station and got onto a train that was going to Zamość. It was Sunday and the work office was closed. I went to a hotel and registered under my new name. I washed up, slept, and the next day I went to the work office. In the work office, there were Poles who worked there, and they had to assemble transports of Poles for the Germans to do forced labor. If you volunteered for this, then they were happy. They understood that these were Jews, but they were protected because they had Polish papers. The officials and the workmen's office told me that I should go to Lublin by passenger train and present myself on Krochmalna Street. Having no other way out I went to the train station again and left for Lublin. On this trip there were Christians whose entire focus was to make fun of Jews: how they are punished, and all this for our terrible sins. I could not participate in these discussions. My heart broke as I passed by Izbica again, as the train station was near the theater. Again from the train I saw Jews around the theater, and guards near them. Naturally they recognized me immediately and they wanted to hand me over to the police. But then a Christian woman who was going to see her daughter in Lublin took me under her wing. She took me to her daughter's home as well because the train arrived at 10 o'clock at night and I had nowhere to go. By now there were no Jews left in Lublin. The following morning, I bought two shirts and some food from the daughter, and then I went to Krochmalna Street. A Christian there dealt with me. “A transport is leaving now,” she told me. But I could not go with him because I first needed a doctor's examination and a disinfection. I told her that I wanted to leave today. She probably understood that I was a Jewish girl, and that same day, at three in the afternoon, we left for Lublin.

After I was taken in the transport, I was taken to a camp where thousands of Christians were already waiting. Among them

[Page 285]

I recognized a few Jews. There I also met Tzivia'le Einwohner and a familiar girl from Izbica. We went together with them until Dessau. We were in Dessau for a few days in a camp of thousands of Christians. There also came a director of a chocolate factory. He selected 40 girls and took them to Dölitz near Leipzig. We arrived to a camp that was specially prepared for us. That same evening, officials arrived from the labor office and took 15 of us. Twenty–five of us remained. Of the 25, 11 were Jewish. There were Jewish girls among us who spoke a poor Polish. Their looks were different from the Polish girls. Also, the religious songs that the Christians sang we did not know – this betrayed us. The Christian girls wrote up a list [of our names] and gave it to the camp director and she gave it to the Gestapo. That same night three girls ran away. They had Jewish friends who worked in the labor office in Dessau with Aryan papers. They went to Hamburg and I saw them after the war.

We, eight Jewish girls, remained. The following morning the Gestapo came to the factory. Each of us was summoned individually into a designated room. I did not reveal myself. Only one of us could not withstand this and revealed herself. They let her stay another three weeks with us in the camp. We thought that they would not take her from us, but one day they did take her from work and I never heard from her again.

This is how our lives in camp began. We worked well and the directors were happy with us. We worked together with German women. After nine hours of work, we went to clean the rooms of the directors. For this, we received a little bit of thread, a pair of stockings, a shirt, because the entire time that we were in Germany we did not have the means to buy anything, and each of us came in one shirt. We were allowed to go to church every Sunday after the first. We, Jewish children, did not go because the Christian girls knew that we were Jewish, so we went to a Jewish friend who worked privately in a business and we spent two hours there. When we were met by Christian girls who did not know us, our Christian girls told them that we were Jewish, so that the entire town's foreign residents knew that we were Jewish. Each ring of the telephone made our hearts race, and we thought now they were coming to get us. We worked in the factory for eight months and when they were short some material to make the chocolate they redid the factory to make it into a waffle factory. Then they sent ten of us girls to work in a courtyard. The rest were sent to the farmers in the villages. Among these ten girls there were five who were Jewish.

[Page 286]

The work here was more difficult but the food was better. We worked in all weathers, in rain and in the cold frost. We had to work in all situations.

I worked there for nine months, and one day I received an order that I should go to the Szczecin hospital to replace a nurse. When I arrived in Germany, everyone was asked about what job they could do, and I said that I was a nurse. I had taken a course in nursing in Turobin during the time of the epidemic and later I also worked in a hospital in Turobin under the supervision of Dr. Hendler. Since the Germans had taken their nurses to the front, they were now looking for foreign nurses. That means, under the supervision of the German state hospital they had put up barracks, and there they took in Russians, Poles, and Ukrainians. The work was very difficult. I was a nurse by day and by night, I was also a cleaner, heat the ovens in the winter, and sleep in the same room as the sick women. More than once, when there was no place – I even slept in the same bed. When I had a free minute I had to work in the operating room, more than once all night, and then begin again regular work in the morning. When I was sick with fever, I also had to do this work. I often heard the argument between the landowner and the hospital director because the landowner needed me back since spring was coming. The hospital director replied that anyone could do field work, it does not have to be a nurse. The hospital won. I remained working in the hospital.

In the city hospital, one of the workers was a Christian, and she was sent to work in the foreign countries and they me to work in the German hospital. The work was easier there because I did not sleep with the sick. I was given a room with two other Russian girls in a barrack. Here, my fears were once more aroused, that they should not discover my origins. I had discussions more than once with the German nurses. They were loyal supporters of the Hitler party. They hated all the races, and especially the Jews. I heard the radio every day in the hospital, I heard the defeats that took place in Russia. We also saw many women dressed in black. We saw that their end was near.

The Germans were convinced that Hitler would distribute new weapons and that would save them. There were also bombings every evening. From one side, this exhausted us physically, I had to help carry down the sick and also medical instruments into the cellar. More than once, we worked

[Page 287]

all night and in the morning, falling from our feet, and we had to go back to work again. But as to our morale, we were very excited. The Germans sat in the cellars and continually crossed themselves. We, the foreigners, continued to recount anecdotes and this broke their patience. More than once we were teased by a nurse, who was a devil herself in human form.

At the end of 1944, we saw transports of people traveling in wagons. We asked them where they were coming from and they answered that they came from Silesia. They were also speaking Polish. They said that the Russians were approaching the German borders and were killing everyone of German origin. This is how every day, transports arrived with refugees. We also felt a disorganisation in Germany. For the sick, there had always been the best food and suddenly, there was a shortage of potatoes and sometimes even bread and other life supports. The stores were empty, even for Germans.

April 20, 1945, we heard shooting. The nurses told us that the Germans were shooting at American airplanes. We began to carry the sick down into the cellars. The shooting lasted all day and in the evening, we went into the hospital and they told us that the American military had marched in. I went outside into the street. We saw foreigners looting the German private homes and stores. We took revenge all night. But this did not please me at all. For me, this was the most tragic day of my life. All this time, I thought that I would not survive. I was without a home, without a family, and without the will to continue living.

I also very soon became extremely ill. For six weeks, I was in the same hospital until I discovered that Dölitz was taking over the Russians. I knew that no one from my family had survived, but I had family in America and I figured that I would make contact with them.

The Americans set up transports in the train stations and all foreigners were able to use them. I and another Jewish girl went until the Szwebis region. Over there, was a camp of only Poles. There were about 10,000 Poles there. The over crowdedness was tremendous. I decided to go work in the hospital. I worked for a few months in a hospital supported by UNRWA. Once, a Pole from Dölitz came to see me in the hospital. He was from the camp security. He said that a tall military officer had come in, an American, and asked about the Jews in the camp. He found it necessary to ask if I would speak with him, then he would wait near the police office. Understandably, I went to him right away…

[lines are missing in original Yiddish text]

Berl Zontag

Translated by Pamela Russ

When I left my home in the year 1939, I still had my entire family. In 1945, when I came back from the Soviet Union, I no longer found anyone. My entire family was murdered by Hitler. But it was not simple for me to find out that they were wiped out, because from our town, as I had heard, only two Jews survived: one was Shloime Fleisher, who had hidden himself in the village Tokary, not far from Turobin, with farmers; and the second, was a woman by the name of Chana Gevirtz, who had hidden herself in many different hideouts, in fields and in bunkers, and in the end, she hid herself in the home of a Polish man, in our town, by the name of Antek Teklok.

When I arrived in Lublin, my only goal was to find the two surviving Jews of my town, from which I had earlier …

[lines are missing in original Yiddish text]

… out. He extended his hand, and greeted me. This was the first time in three years that I heard a Yiddish word. I told him about my tragedy. Then he told me that I wasn't the only one, that not far from the Szwebis area, there was a camp of only Jews. He himself was a rabbi of the American Jewish military. His father was connecting families of Americans with the survivors of the Holocaust. I gave him details about my family in America and within ten days, I received a letter from my cousin.

I immediately presented myself to UNRWA as an orphan and I received the appropriate papers to go to America. Meanwhile, I found out that an uncle of mine had survived, but he was very sick, and I decided to take him to Germany, because now he was with strangers. The border between Germany and Poland was open. I went to Poland, but I was not able to take my uncle to Germany. He had become paralyzed. I was with him for four months until he died.

I was no longer able to return from Germany, because the border was now locked. A little while later, I got married and settled in Szczuczyn. My husband and I registered in the Haganah to go to Israel. I could no longer step on the cursed Polish earth. In 1948, we left Poland to go to Israel to build our new home in a secure way.

Tragically, I was one of the only people of Turobin to survive.

[lines are missing in original Yiddish text]

[Page 289]

heard that they were the “one in a thousand” in order to find out who in my family was still alive. All day I am wandering through the streets looking at every face, maybe I will find someone from my family, because there were Jews who told me I should not go to my town. From these very same people I found out that right after the liberation of Turobin the first young man, by the name of Motel Fuks, a hat maker arrived. The Poles murdered him. After him, another man by the name of Yosel Kofef arrived and he also had the same ending as the first young man. When I heard this I decided not to return to Turobin.

I decided, at any cost and no matter what to look for one of the two surviving witnesses. I and my friend Yitzkhok Leikhter, with whom I had come from the Soviet Union, walked through the one street that was sparsely populated with Jews, Lubarski Street, and we looked for the two surviving witnesses who would tell us about the final fate of our families. Yitzkhok Leikhter also left his father behind when he left home. This was Moishe Leikhter, with sisters and brothers and also his whole family from his mother's side. This was from the Aron Diamond's dynasty.

Hour to hour, our nerves became more tense because no matter which Jew we asked about Khana Gevirtz the answer was always that she was in Lublin, but where she was living now, nobody knew. So we decided to go to the market and search among all the Jews who were there, maybe we would find her as we were looking through all the Jews from our town, because with all the Jews that we were seeing now, it was possible that we were seeing them for the first time in our lives but they were so similar to us and so close, as if they were from my own town. I feel a foreignness to every non–Jew and have a strong feeling that no matter where I turn, I am in an ocean of hatred. Every Jew is being stabbed by the Poles with their gaze. They also did not believe that they would ever see a Jew in front of their eyes and wherever the Jew would be, he would always look all around him [in nervousness]. One Pole smiles to the other, as they say: “There is still some merchandise left for us, we cleaned so many of them away, we will be able to get rid of these as well. But meanwhile, the Red Army is bothering us a little so we have to hold ourselves back, but the time will come…”

I swear to you that walking through the streets of Lublin the moral pain was so great exactly as if I would have been physically beaten. If not for the fact that I had to look for my fellow townspeople, I would never have come to these streets. If you would see how the Poles are standing in the stores where Jews used to sit for many years, and how the Poles are over–stuffed as fat pigs, and they are the ones who helped get rid of the former businesspeople by sending them to Majdanek, where

[Page 290]

all that remains is a pile of ashes – the Jew is left with only one wish [Hebrew]: “ Timkheh es kol hayikum me'adam asher al pnei ha'adamah” [Yiddish]: “God's Hand should bring a flood to the entire world, and the world should go back to vastness and emptiness.” There should be no human dominance over the world, let the wild animal be the actual leader on the earth, because that is what he was created for. He has not lost any of his animalism. But the person, who, throughout all this long time has raised his humanness, in one minute, lost his whole human form.

But the wish remains only an actual wish. The world is not going under and meanwhile we have to become aware of that which is already been lost. For that goal, we continue our search, and we have found it.

I will always remember the moment when I went to the place where Khana Gevirtz was standing. When I saw Khana from a distance, I recognized her right away, but she asked us what we wanted. At that moment we did not answer her. I was thinking to myself that that which I wanted, no other person of another nation could want (“I came to you to get Job's news”; referring to the Book of Job and reports of all the suffering). The fact that we did not give her any answer forced her to think about us and then in a minute she recognized us. She broke out in a hysterical cry. “Is it you, Berl, the son of Yerakhmiel and Frumit Zontag?” And she immediately added, “Yes! There is a memory left of you but from me and of my nineteen souls, not one person is left.” And Khana Gevirtz begun to tell me how the first pogrom came about in Turobin.

This was May 15, 1942. A troupe of Germans came into Turobin only for a few hours. Whichever Jew fell into their hands was dragged into the home of Velvel Liberboim. In that manner they herded together 33 Jews among whom was her sister Frimtche. This was the first murder in Turobin and at the same time she was the first victim in the family. The one who helped the Germans was the well–known enemy in the town, Genik Brankewycz, may his name be erased, a terrible anti–Semite and hater of Jews. Another assistant in this slaughter was a Pole who worked for Weiler as a shoemaker. When the Germans completed their murderous act and saw that all the Jews were already lying spread out on the ground, they left the city. At that moment, the above–mentioned Poles went over to see if anyone was left alive, they noticed that one person who was lying there was moving. This was Fajtche Liberboim, the daughter of Velvel Liberboim. When she lifted her head and saw that the Pole was standing next to her, she pleaded with him that if he would let her live she would give him all the possessions that she had. But the Pole answered her:

[Page 291]

“You, Jew, lie down and I am going to shoot you.” Nothing helped, she lay back down on the ground and he shot her.

This was told to us by Jontche Feder, the son of Moishe and Mindele Feder, who was the thirty fourth Jew in that murder event, but he was only wounded slightly and was able to run away and recount everything that happened there. On that day, the entire Liberboim family was murdered – from young to old with the exception of the youngest daughter Sheva Liberboim, who was not home at the time.

After that episode, Jewish life was already chaotic, bands of city Poles assembled under the direction of the Brankewyczes and the Wages. They organized the so–called firemen whose job it was to stand on the roads and not permit the Jews to run away from the city. When they captured a Jew on the road trying to run away, they brought him back to town to the German police, or they themselves did the job. In many cases, nevertheless, some Jews managed to run away to nearby villages where they thought they would be able to save their own lives. To deal with this, the Poles from the city organized the so–called firemen from among the farmers of the surrounding villages. Their job was to find the Jews who were hiding in these villages and we have to say that the Polish farmers fulfilled their tasks to perfection. When a fireman knew that a Jew was hiding somewhere, he dragged him out of there. If he wanted, he was able to kill him on the spot. In many events they would capture the Jews, tie their hands with rope and summon the farmers, and then take the Jew to town to the German police. All along the whole way, the Jew was tortured with all kinds of pains to show the German authorities how loyal the citizens were.

This is what the only surviving woman of our town Turobin, Khana Gevirtz, told us. Her children remained in hiding along with other Jewish children, in her house. Some Poles, along with Genik Brankewycz, their commander, went in there and asked her where she had hidden her children. She answered that she did not know. One can only imagine the moment when murderers come in to a mother and ask about her children and she knows that they are going to their certain death. She knows that her own children are lying hidden in her house with children of other Jewish mothers, and she must remain silent. The murderers of the Polish nation go around the whole house looking for Jewish sacrifices to slaughter on the altar, which means remove them from the nation of Israel. But this time the sacrifice will not have an altar nor a designated time, but where it is found and when it is found, the Jewish lamb can be sacrificed in any house, in any place

[Page 292]

in a city, in a village, in a field, in a forest, wherever you find it. Every soul that carries the name Jew is fitting for a perfect sacrifice, a slaughter of people who belong to other nations.

The murderers continue to take Jewish children from the hideouts. Among these children is also her son Pinkhas. The children are taken away not far from the home and then they are shot. This is what elderly Khana tells us. This is already the second sacrifice of her children and the mother of these children sees that the situation is so bad and tells all the other children to quickly leave the house. The children go on the road that leads to the village of Czernieczyn. But on the way, the commander of the Turobiner firemen, Genik Brankewycz, may his name be erased, captures them. He takes them back to the city and the German police orders that they be thrown into prison. Tomorrow they would all be shot. The old mother knows all of this and also that her children were in the prison and that the following day they would all be shot. This mother sees that all is already lost so she herself decides to go to the prison to be with all her children. She wants to die with them but she is successfully able to bribe the Polish guard of the prison and the children manage to flee from the city. Mostly, it was men who were taken captive with the express idea that they were needed for work. For that reason she sends away her son and the daughters remains with the mother.

Chana also knows how they took out Avrohom Boimfeld with his only son Shimon, Moishe Szternfeld, Yechiel Kupfer, and Moishe Kopenboim and a few other Jews in the Olyszanker forest across Wantrubka's brickyard, and then shot them there. She also knows that my father's brother and son by the name of Shachna Zontag was shot by Germans in the village Tarnowa, together with his wife and child, and along with them, also Avrohom Boimstajn's son. They were taken behind the city on the wagon and they were shot behind the house of Sweis Miller. They were also buried there. Chantche Shmelke's was shot when she was just giving birth to a child. She also knows about each time hidden Jews were brought from the villages since there were no Jews left in Turobin. At that time, she was hiding at the home of a Pole whose name was Antek Teklok. The Jews of Turobin who knew the abovementioned non–Jew would never have said a good word about him. They would never have thought that he would risk his life by hiding a Jew in his home.

After all the evacuations, the Polish farmers brought a Jewish family from Turobin into the city. This was Daniel Krajtman with his wife Golde. Their children, it seems, had a place where they were able to hide illegally. In the end, the farmers found them and brought them to Turobin. The joy of the Poles was without bound because this happened long after there were already no Jews seen.

[Page 293]

When they were taken through the streets of Turobin, they shut their eyes tightly out of great pain so they should not see what was going on around them. Young and old from the “good Polish society” of Turobin gathered around them to greet them and see these “wild animals” that call themselves Jews. For these Jew haters, this was simply the greatest pleasure in their impure hearts, that after such a long time, after they had already sent out with the second evacuation all the Jews from Turobin, a whole Jewish family came into their hands, the family Kreitman and their children. The Poles, with a bitter irony, persisted in asking: “How were you able to hide for so long and what kind of audacity do you have to stay alive, at the time when all the Jews have already been killed?” As they were taken through the streets of the city, every Pole wanted to fulfill his mitzvah of wiping out the Jewish nation until the very last Jew, because it did not occur to even one of them that this was not the last Jewish family of Polish Jewry in general, and of the Jewish community in Turobin specifically. Therefore, everyone slapped them around, and the youth of the Polish thugs tore pieces of the clothing that the family had on them so that in that way they could fulfill the mitzvah of wiping out the last Jewish family in the town of Turobin. After taking them to the streets, they were taken to another place and all of them were shot.

All of this, the only living survivor knows to give over, as she herself saw all of this. After that, since she was in hiding, she knew that she would give this over as an actual witness. As was mentioned above, Khana was in hiding by Antek Teklok in the attic, and when the man of the house came at night he told her everything that happened in the town all day. One thing I cannot find out from her is the exact dates of events, for example the month or the day, and that is because of her gruesome experiences. There were 29 people in her family, her own children and grandchildren, and with her own eyes she saw how each one of them was bestially murdered. Fate had it that the old mother and grandmother should be the only one remaining alive of her entire family. No wonder she is completely broken and cannot give over exact dates. She does know that all of this took place in the year 1942, meaning that all the killings began in the year 1942. The first evacuation was at the beginning of 1942 when the Jews of Turobin were taken to the train station to go to Izbica, to the Lublin circle, and where they arrived after that, nobody knows. But according to the survivors they were taken to Bełżyce. The second evacuation took place in the month of Cheshvan [October] 1942.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Turobin, Poland

Turobin, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 07 Mar 2019 by JH