|

|

|

[Page 59]

The disease of suicide took its victims even in the Satmar ghetto as in every other Hungarian city, even though no one in our ghetto knew what was happening in the other ghettos.

There were Jews who were not prepared to live through the disgrace and the tortures. They could not make peace with reality. Instead of falling victim to the Nazis they preferred to take their own lives; to drink the hemlock and relocate to the “world where all is good.”

In my introductory words I already described 30 funerals which we organized, nine of them suicides. Each had its own story. From among those nine I recognized only eight. The name of the ninth escapes me. The eight are listed alphabetically:

Anna Donash

Anna Donash was Sandor Donash's second daughter. Her father was the editor-in-chief of the Hungarian daily newspaper the Samosh. She ended her life when she was twenty years old after losing confidence in her plans to marry her Protestant fiancé.

Although he was among the most loyal members of the Hungarian party, her father was sent into the ghetto along with his family. Despite two decades of complete cooperation with Albert Pigosh, may his memory be blotted out, and other Hungarian aristocrats, no one lifted a finger on his behalf. Even Geza Ember, a member of the parliament and Franz Kotzai who was the district governor, failed to come to his aid.

The beloved fiancé didn't do anything to save his fiancée from the ghetto. He could have hidden her without great difficulty but he didn't. When he learned of her bitter end he quickly organized a Christian funeral and burial in a Christian cemetery. He made sure that her body was clothed in a pink silk dress and silk stockings, a ribbon tied on her head and placed in an elaborate coffin with a bottle of perfume at her side.

This author placed her inside the coffin fully and elegantly dressed assisted by her bereaved fiancé. Before the funeral an official delegation inspected her body. This author was ordered at gunpoint to remove her clothing. The memory troubles him so much that he prefers not to recall it in writing.

An hour before her funeral her older sister and her brother-in-law Laslo Baradali came to say goodbye. I begged her sister in the presence of her husband, “Dear lady,“ I said in a voice choked with emotions, “let us give your sister a proper Jewish burial in the Jewish cemetery.”

Kato Donash shook her head, “no.”

I didn't give up and continued to request my voice full of emotion and tears running down my face. “Dear lady, don't you feel the knife at your throat? Can't you see what the Hungarians have done to you?”

Kato Donash turned to me, her face full of pain and her eyes full of tears. “My dear Rabbi,” she said “it is an irony of fate that my sister will be laid to rest in a Christian cemetery.”

And so it was. She is buried in the Christian Protestant cemetery near the train station. The church baptized her as is their custom but she was dirtied by her own family. Rest in peace Annaleh. Dream about your engagement and about your fiance's lack of responsibility.

Dr. Shamu Fekete

Dr. Shamu Fekete, an opthamologist, was born in Satmar. He was the son of Albert Schwartz. He lived on Arpad Street near the district house (for his picture and the story of his military career see the album of army veterans). Dr. Fekete earned many merits as one of the leaders of the Status Quo community. He earned even more merit in his career as chief physician at Satmar's Jewish hospital. The hospital operated at a high level under his leadership together with Sandor Meir Czengery z”l.

Dr. Feket organized a hospital in the ghetto inside Dovid Yehoshua Gross's straw hat factory on Petofi street. Tragically, Dr. Fekete was the first person to die in this hospital. He ended his life by drinking poison. Even though he was a specialist he made an error in a diagnosis. The strychnine he prescribed to himself failed to defeat his strong constitution and he suffered for three days before his passing.

The government “generously” allowed his family, his wife, his two daughters and his son-in-law, the engineer Borosh, to accompany him to his final resting place.

It was already night. I instructed the grave digger to bury him next to his father Albert Schwartz but his wife, Mrs. Fekete pointed to an empty grave next to her father, Yaakov Reiter, and she said “let my husband lie next to my father.”

“Dear lady, I said,” That place is meant for you after 120 years.” Mrs. Fekete insisted. “Dear Chief Cantor,” she told me, “Do you really believe that I'll be buried in this cemetery? I don't believe that.”

To the best of my knowledge no one from that family survived the war.

[Page 60]

Sandor Garo

I already made reference to Sandor Garo's tragic story In my introduction. He was a victim of the money beatings. A good hearted and honest man he could not bear the terrible tortures and challenges. He ended his refined life in his ghetto apartment (the Schweid house on Zarinyi Street). One of the other residents found him dead.

We had to inform the police. A group of policemen came, including the evil Captain Dr. Sharkozi, may his memory be erased, and a doctor named Mairosh. The body was laid out on a table and I was instructed to remove the clothing. Bruises from beatings, open wounds, and oozing blood were clearly visible on the body.

Garo's personal physician, Dr. Tibor Koevary, was brought in to testify. He explained in no uncertain terms what Garo had told him the previous day when he turned to him for first aid. He pointed to the wounds and said, “I know how this happened. These wounds are the result of the terrible beating he received in the house of the money beaters, which forced him to reveal where he'd stored his treasures.”

The policemen raised their eyebrows making light of Dr. Koevary's accusations. “This is a Jewish fantasy probably taken from the Talmud,” they said. “This is impudence to besmirch the good name of the Hungarian government. The idiot Dr. Koevary will pay the price. We will teach him to not spread rumors.”

Sandor Garo was buried on that same day in the Status Quo cemetery in the first room on the right next to the grave of his wife who had passed away not long before he died.

If they had brought me in to sketch this pillar of fire in the book of disgraces, we could compete with our Polish brothers.

Dr. Oscar George

The beloved physician Dr. Oscar George ended his life by taking poison in his medical clinic on Mother Janosh Street. Shall we say that it was a stroke of luck that he was found and hospitalized in the city hospital on Istvan Street where his stomach was pumped and his life was no longer in danger? No.

While he was being treated the Sisters of Mercy organized a mass and prayed for his life. When he regained consciousness he asked one of the nurses to bring him a box of cigarettes. Dr. George used those moments when he was alone, to remove a pajama sleeve and stuffed it into his throat, choking himself. When the nurse returned with the cigarettes she found him dead.

His funeral took place at five in the afternoon. Together with my friend Berkovitch, we arrived at the morgue an hour and a half earlier to transport the deceased to the cemetery. We went down the morgue and laid the body on a stretcher to transfer him to a Black Maria waiting on the street. We were too exhausted to lift the stretcher so I went to find help.

Oh G-d, what did my eyes see?

Several hundred mourners had gathered in the public square next to the two hospitals (one operated by the Brothers of Mercy). Men and women dressed in black, holding bouquets of flowers, came to pay their last respects to Dr. George, their beloved physician as the news of his death spread through the city.

I was uncomfortable with this. Who knew? The authorities could accuse us of organizing a demonstration. That was all we needed. I went back to Berkovitch and I told him what I suspected. Berkovitch agreed with me and suggested that we wait a half hour but waiting did not help. The crowd of mourners continued to grow.

The shouts could be heard all the way to the basement. “We want to see our dear Doctor! Why did he do this to us? He saved my child. He healed my wife. He returned my husband to me,” and so on.

We were terrified. What would happen? A crazy idea entered my head. I went out and climbed on the roof of the Black Maria. I lifted my arms and demanded quiet. The crowd complied. “Ladies and gentlemen,” I yelled. “I thank you very much in the name of the late beloved doctor for your expression of love, but please consider us. We will be accused of organizing a demonstration. Please go home quietly. You can return to the Jewish cemetery at five where you can quietly say goodbye to your beloved physician.”

The crowd complied. Everyone scattered silently and we gathered our strength and lifted the stretcher. The horses lifted their legs and ran with all of their strength. We purified the body, dressed it in shrouds, and buried Dr. George quickly in order not to start another demonstration. The following day we heard that a large crowd had gathered for the funeral and returned home disappointed.

[Page 61]

Dr. Gustave Rovoz

Dr. Rovos was an ear nose and throat specialist who ended his life by injecting himself with poison in his ghetto apartment on Petofi street (the home of R. Joseph Freund). His neighbors found him dead. Next to his body was a baptismal certificate from the Catholic church in Tur Terebes, proof of his 1941 conversion. The certificate was stamped by the heads of the church. His close friends and family said that the reason he took out the certificate was to demonstrate his Catholic faith and his desire for a Catholic burial. I was tasked with the responsibility, a mitzvah, of removing the body near the well on Bathory Street where the priest and his entourage awaited us. Even from a distance I could already smell the incense with which the priest would “sanctify” Gusti.

I laid him down in a coffin. Gusti Rovos is not alone in his grave. He has a partner. The coffin was constructed with a huge gold leaf cross, and on it rested a 10 meter statue of Jesus. I want to point out that Dr. Rovos also injected his widowed mother and his wife, Dr. Blanca Kasriel, but they were saved and then deported to Auschwitz where they were murdered. I'm not qualified to express an opinion but I felt that this was a kind of double murder. The murder of the mother and wife (even though both survived). Only G-d can judge this matter.

Yehuda Stern

Not many people knew him in Satmar. R. Yehuda Stern was pleasant and pedantic with his small beard and his walking stick in his hand as he took his daily walk on Antal Farkash Street near the white house.

This elderly man arrived in Satmar only a short time before the Nazis. He had arrived from Berlin where he had lived for many years. He was the brother of Stern Baci, the fish store owner.

The event took place on the first day of Shavuot. All of a sudden I was awakened early in the morning in my ghetto apartment (the house of the Talmud Torah on Petofi Street). I was asked to come quickly because of the man they found hanging in the attic of the Schwartz bakery on the corner of Bam and Bathory Streets. I arrived at the place and in the courtyard where a large group of onlookers had gathered. I grabbed a ladder and climbed up and found R. Yehuda Stern's body hanging from a rope. I recognized him from his walks. His body had hardened. He had been dead for several hours. I didn't want to touch him without permission from the police and I did not have the strength to take him down on my own. Meanwhile I looked around the attic. Next to the deceased I found a sealed letter and a small medicine bottle sitting on a box. He wrote, in Yiddish on the envelope, “To my dear ones.” A note on the bottle indicated that the contents was poison. After several minutes Dr. Sharkozy, the chief of police, and several other officers arrived and pronounced R. Yehuda Stern, dead. They said that the deceased wanted to commit suicide, he drank half the bottle of poison but still had enough strength left to hang himself.

Sharkozi's sharp eyes quickly turned to Stern's vest pocket where he discovered a large gold pocket watch attached to a long gold chain. Sharkozi grabbed the watch and slipped it into his own pocket and said, “I am confiscating this for the Barosh organization. I'll send a receipt to the Jewish community.”

Don't bother, dear captain, I said. I'll let them know.

The monster removed his gun and lifted it to my face and said, “if you don't shut your mouth you'll get a bullet right away.” I had seen this before and I was already used to his threats and so I kept quiet.

After that I pointed him to the letter. Sharkozi threw the bottle to the side. He ripped the envelope and removed the letter written in Yiddish, and said in shock, “this is written in Mosaic letters.” Sharkozi handed it to me and said, “translate it word for word into Hungarian. I'll give it to someone else. If you tricked me you'll also be buried today.”

Thank G-d they didn't bury me. I translated the letter into the purest and most flowery Hungarian. When the bandits heard the translation their faces turned colors. Sharkozi banned the disclosure of the letter's contents but to you, my dear ones, I shall reveal what Mr. Stern wrote. “I ask forgiveness from my beloved family for the pain I have caused them.” Most of the letter is about family related business, written with a clear sense of humor that came forth even during these difficult final hours. He ended the letter, “Hitler rose to power in Berlin in 1933 and I escaped to Vienna. In 1938 he followed me to Vienna. I escaped to Budapest. In March of 1944 he chased me to Budapest. I escaped to Satmar. After several days he followed me to Satmar and I escaped to the place where I am now. I invite him to follow me for the fifth time.” Sharkozi grabbed the letter and said “you'll lie in the cemetery today.” With G-d's grace I have survived 40 years since that day. We buried R. Yehuda Stern on that same day in the Status Quo community cemetery.

[Page 62]

Albert Weiss and his wife

The double suicide of Albert Weiss and his wife was the worst of them all. They chose a terrible mode of death that was hard to witness and hard to write about even decades later.

Albert Weiss had been well liked and widely respected. He owned and operated a glassware and crockery store located in the central square. The Weisses didn't wait to be herded into the ghetto. To avoid suffering and disgrace they ended their lives in their home on the corner of Tompa Josef and Pohartzag.

Both were nearing the age of 80. They exhibited superhuman courage by choosing this form of death. It is hard to find the words to describe what we saw when we entered their apartment. It was a terribly disturbing image of body and soul revealed before my eyes. Mrs. Weiss lay lifeless on the carpet. Next to her was her poisoned puppy. Her husband's body hung on a clothing hanger opposite the mirror. It was a strange sight because Mrs. Weiss did not have a rope around her neck even though there were signs of pressure on her flesh. Where did the rope go?

The apartment had been locked from the inside. We had to break in. It is possible that Weiss hung his wife and after she died he removed her to the rug, untied the rope from her neck, and hung himself. Terrible.

I have seen many terrible things. I can visualize the scene now. I saw two images of Weiss hanging from the clothing hanger. One is the real Weiss and the second, his image reflected in the mirror, the eyes of the couple looking at each other.

The Weisses prepared their own white shrouds, the tachrichim, left on the living room couch. Albert Weiss also left out his tefillin not realizing that they were not needed. He left a will as well, declaring that all their property was bequeathed to the Status Quo community.

The delegation provided a burial license. I asked permission to take the shrouds but the legal advisor refused. As I appealed to his conscience, I hoped my simple words would penetrate his heart to allow me to take the kitel. I swallowed my pride and said, “As the ritual administrator of the Jewish community I am prepared to testify in the names of the deceased. Let me take them all.” “Then take nothing,” said the official. When no one was looking I stuffed two pairs of the Weiss' white socks into my pocket. At least let them wear those.

The deaths of the Weisses and Dr. Oscar George took place on the same day.

I did acquire proper burial shrouds for all of them. By this time, the doctors had already been sent into the ghetto. I went to see Dr. Albert Bozshai on Rakozy Street to tell him what had happened and to let him know that I needed shrouds. Dr. Bozashai opened his clothes closet and told me that I could take whatever I needed.

All three were buried in the Status Quo cemetery. I must point out that according to the rabbinical court these suicide victims were declared worthy of a full Jewish burial.

After the war there was a possibility of transferring Dr. Rovoz and the maiden Donash to the Jewish cemetery. But there were countervailing halachic considerations. Even though one is a sinner one is still a Jew, but the personal desire of the deceased is to be respected. And so they remain in the burial place of their own choosing.

Forty years have passed since then and as I wrote in the introduction the memories fade slowly but not the truly horrible memories. All that I wrote here is not the product of my imagination, it is all correct and true.

Bnai Brak tisha B'Av, taf shin mem alef (1971).

|

|

|

The Hungarians were masters at finding ways to disturb the peace of the Jews. One of these situations occurred on Shabbos, the last day of Passover taf shin daled (1944).

In general, we were mentally prepared for unpleasant events. The blowing winds brought all kinds of rumors. Nerves were frayed. There were rumors that the Jews were to be locked into ghettos as they had in Poland.

As German soldiers retreated from their defeat in Stalingrad, they passed through Satmar. Like a drowning man holding onto a straw we held onto the hope that the German defeat would save us, but it wasn't to be.

One day while the retreat was taking place we buried Giza Roth, an elderly man from the Mohi Palace. His funeral passed through Atila Street on its way to the cemetery. We were shocked by the behavior of the retreating German troops, the politeness of the soldiers, and even their respect as the funeral cortege made its way through the streets. Once again we felt hopeful.

Arpad and Atila Streets were crowded with people. And even though the German soldiers recognized that this was a Jewish funeral, they stopped and stood still on both sides of the road so that the funeral procession could continue on undisturbed, and the officers even saluted out of respect for the deceased.

In this atmosphere we celebrated the holiday of Passover.

The synagogue was packed with worshipers on the final day of the holiday, as this was the day that the yizkor prayer was recited. The morning prayer and the Torah reading proceeded undisturbed and just as we started the silent amidah at musaf I took the amud, prayer stand. I heard strange noises behind me, but I did not want to turn around to see where they were coming from. After completing the silent prayer, I realized that I was surrounded by three or four armed Hungarian policemen, German soldiers holding bayonets in their hands, and two or three others in civilian garb. The doors and windows were guarded by armed soldiers.

I tried to appear calm. In the meantime one of the civilians approached me and politely asked, “Excuse me, are you the chairman of the synagogue?”

“No, I am the cantor,” I answered, trying to sound calm.

“Please show us where the office is from which you communicate with the Russian army.”

I answered that there wasn't any such office in the synagogue. “Please,” he continued politely, “don't deny it. We have information on your activities. It is better that you show us the office.”

Now I was afraid. Maybe someone secretly established an office in the synagogue? “Please take us there voluntarily. It will be better for you.” I tried to explain that there was no such office and there never had been.

“Then we'll have to use force,” he threatened. “Please,” I answered. “The information you are referring to sounds like an invention and a slander. Too bad that you didn't arrive a quarter of an hour earlier. You would have heard our prayers for the government. We recite these prayers for the Hungarian government every Sabbath and holiday, even though the current government doesn't treat us with kindness. We still recite it as a mitzvah.”

“Dear Rabbi, all of this sounds very good but the office is here.” “No,” I repeated. “There is no such office.” I was losing my patience. “If you won't take us there, we will find it on our own,” said another man who stood at his side. I moved two or three steps back and the soldiers and policemen surrounded me.

[Page 65]

The investigator went to the prayer stand, pulled out the drawers and removed the prayer books and prayer shawl, and upon inspection, failed to find incriminating evidence.

“Nu, there's nothing here. Let's move forward.” Two or three ascended the steps to examine the holy ark but were unable to open it. They asked me to open it. The shelves held more than twenty Torah scrolls. As the investigator began to move them, I lifted my hand in request and said, “Sir, It seems to me that you are a religious man. You also have sacred objects in your faith. These are the holiest objects for us. Please let me remove them to a location that befits their dignity with someone's help.” He agreed.

I summoned the beadle of the synagogue and together we moved some of the Torah scrolls to the table where they were read, and some were held by people who sat nearby. The empty Holy Ark stood behind us. The investigator took out his tools. He removed the boards from the sides and back of the ark revealing the red bricks that were behind. He looked carefully in every corner, not finding anything.

Then he turned to me and said, “Today you were lucky,” and he left. The congregation breathed a collective sigh of relief, and left for home before the service ended. I am not sure that I finished reciting my prayers.

On my way home I heard that the same thing happened in each of the synagogues and study halls in Satmar. The frustration and disappointment was total but that didn't help us.

|

|

First row from right: Yosef Katz, Sandy Fisher, Emil Fisher, Yosef Frank Second row from right: Layosh Schwartz, N. Leibowitz, N. Niederman, Azriel Wertheimer |

This article was published under my name on April 10, 1952 in the Hungarian Jewish newspaper in Buenos Aires. Because it concerns the Holocaust in Satmar we felt that it belonged in our memorial volume.

An interesting guest just arrived on the ship, Transylvania, among the new immigrants arriving from Rumania.

Refreshed and healthy, the 83-year-old woman from Satmar descended from the ship. She was Auntie Pollak, who had been eulogized and mourned for ten years. Everyone who loved her cried the customary tears at her passing.

And this is what happened. There was a very well-liked man in Satmar, Michel Pollak the tailor. In 1940, as a result of the return of Satmar to Hungary, Monya was separated from his elderly mother who lived in the Rumanian part of Transylvania.

Some Rumanian Jews were deported to Transnistra across the Dniester River before the Hungarian Holocaust, and among them was Auntie Pollak.

In the Spring of 1943, Michel Pollak received an official notice from the Rumanian consul in Budapest informing him that his mother perished in the camp and had been buried there. As a traditional Orthodox Jew, Pollak tore his clothing and sat shiva and recited the kaddish prayer for 11 months and even recited the kaddish on her first yahrzeit in the spring of 1944.

In the Dorhau camp in Germany, where I was interned together with Pollak, I participated in a minyan on his mother's second yahrzeit in 1945. After the liberation in early summer 1945, I returned to Satmar together with Pollak. We were broken and agitated in our spirits and our bodies, our hearts pounded with the hope of being reunited with our families.

Pollak, who lost a large part of his family, thought about his mother who had passed away two years earlier. When he knocked on the door of his home on Tombad Street and saw a sweet old woman opening the gate he recognized that she was his mother.

“Shema Yisrael!” Pollak shouted. And then he fell into his mother's outstretched arms, willing himself to overcome his shock. And now the son greeted his mother at the port in Haifa and hugged her after being separated for two years.

The other Satmarers in Israel joined in Pollak's joy and we welcomed Auntie Pollak. After a great deal of thought I concluded that another elderly woman with a similar name perished in the camp and was mistaken for Pollak's mother.

After a number of years, Michel Pollak relocated to Belgium where he died in Antwerp. Auntie Pollak died and is buried in the cemetery in Kfar Ata.

We thought that a humorous description of one of our dear and beloved Jews would not detract from the dignity of our volume. If this will cause bitter feelings among our readers, please accept our forgiveness. I assume full responsibility for the veracity of what appears below.

This incident occurred in Satmar in 1943 when the Hungarian version of the Nuremberg racial laws banned Jews from various trades and professions. These laws paralyzed Jewish businesses throughout Hungary.

Yaakov Fischer lived on #36 Toltash Street. His nickname was Uncle Kapely or Kapelybasci in Hungarian. The new laws hit him hard. Kapelybasci was a pious Jew devoted to the Torah and mitzvot, his beard white and long. He was a regular worshiper at the Great Synagogue and he supported himself by collecting small quantities of duck and goose feathers each day, which he sold once a week to a dealer.

His efforts earned him a poor living, enough for his daily bread and a bit of meat for the Sabbath (at that time beef was cheaper than chicken). With his small earnings he was able to purchase medicine for his sick wife. A police officer trailed him and found him leaving 42 Petofi Street with a small bag of feathers tucked into his long coat.

“Stop, now I've caught you red-handed,” shouted the policeman. “Move forward.” Poor Kapely trembled as he approached the officer. Hardened criminals like Kapelybasci were taken before the anti-Semitic police magistrate, Dr. Torzshok (Sharkazi's partner) and after a brief investigation he rendered the verdict.

Kapelybasci stood before the judge trembling as his lips murmured silent prayers.

Magistrate: “Nu, old lawbreaker, I'll make sure that you won't have to collect feathers for a long time. Do you know what offense you are being charged with?”Kapelybasci: “Yes, I know, oh merciful one.”

Magistrate: “Don't flatter me with your putrid mouth. What is your name?”

Kapelybasci: “Yaakov Fischer.”

Magistrate: “Where do you live?”

Kapelybasci: “At home.”

Magistrate: “Nu, in a nest of vermin? Do you think we study Talmud here? Where do you live?”

Kapelybasci: “#36 Toltish Street.”

Magistrate: “And your age?”

Kapelybasci: “Seventy years old.” In Hungarian this statement has a double meaning. It could mean seventy or two weeks old.

Magistrate: “Nu, putrid one, how dare you poke fun at the Hungarian court? You will suffer for your impudence.”

Kapelybasci: “I am not making fun. I am two weeks old.”

Magistrate: “Is this some Talmudic commentary? Tell me, how old are you?”

Kapelybasci: “Two weeks.”

Magistrate: (his face beet red) “Now you'll need to suffer. Do you know how to write?”

Kapelybasci: “Yes.”

Magistrate: “Come here and write down your age.”

Poor Kapelybasci, approached the bench, and with shaking hands wrote 7 7. “This is my age, your honor.”

The word Het means seven in Hungarian but the word Hetes also means seven. It turns out that the phrase ket ketes means seven twice 7 7.

The magistrate said, “Leave here, you old warlock. I hope I never see you again.”

Kapelybasci didn't wait to be called again. He ran out without looking back, ruminating about the words G-d placed in his mouth and how he was freed from certain imprisonment. That's how Kapelybaschi was two weeks old at age 77.

In the year of the Hungarian inquisition, the eve of Yom Kippur fell out on a Tuesday, and within the camp the excitement was palpable. We had hope and high expectations.

As for my own life, what I succeeded in accomplishing on Rosh Hashanah I could not do on Yom Kippur. The doctors hospitalized me under observation with the clear intent that I serve as the cantor for Rosh Hashanah services in the hospital. Along with that I hoped to receive the special food allotted to the doctors.

It wasn't that way on Yom Kippur. The Germans had made plans to interfere with the prayers as they had done in the past.

As in Satmar, we attempted to meet up with our family and friends and wish them a gmar chatima tova. The Germans met us at night to demonstrate to us what they were capable of doing. We gathered in the bathhouse for the Kol Nidrei service. The room was illuminated with candles and there was a large crowd of worshipers. I stood before the makeshift ark and repeated the Kol Nidrei for the second time. All of a sudden we received a cold shower. The lights went out and we were chased outside with sticks and whips, a scene I can't get out of my mind, even now. This was Kol Nidre night in the Wolfsberg camp.

The next day was Wednesday, Yom Kippur. We rose early as if it were an ordinary day and went to our work place, seven kilometers away from the camp. It was hard to walk in the cold and damp from rain and snow.

I carried my great treasure in a pack on my shoulder: a slice of dry black bread and the tail of a salted fish. These were my food reserves. Work continued at its normal pace all morning. The bleak weather made fasting easier but it made the work more difficult.

As I worked, my lips mouthed whatever bits of the morning prayers I knew by heart. As a result of our poor diet and my weak body I began to crave my piece of bread and fish. Now it was noon, the time we usually ate.

For those who were in camp in Germany there is no point in describing the kibli (the large food container which retained heat like a thermos) and its poor contents. In addition there were several others who had fasted until the afternoon. My poor brothers among them, my dear friends from Satmar, approached me and asked “what should we do? Do we continue to fast?”

I answered them in a choked and weak voice, “do the best you can. Whoever eats is not a sinner because you are eating in order that you will have the strength to worship G-d in the future. Don't worry. I will continue to fast.”

Dear readers. It was as clear as the sun that I put myself in grave danger if I didn't join the line to receive my food. Many approached me. “Stern, are you going to take your portion?” “No,” I answered. “Then stand on line and give it to us so that it won't be wasted.” “Don't be angry with me,” I said, “but today stick to your own portions. Today I can't give you my food because you are not in danger.”

During our lunch period we managed to recite the kedusha together as well as several other prayers and at one we returned to work. On that day I worked in an especially rocky field.

While working at 2 pm, I began the musaf prayer singing the melody to the beat of my hoe. When I reached the avodah section of the prayer, about the temple high priest, I chanted the prayers to the holy melodies and bowed during korim, where one falls to the floor. I suddenly felt extremely weak. I thought I reached the end and began to cry as I did when I stood before the ark in the synagogue in Satmar. But this time my tears were bitter as my thirty-five years of life passed before my eyes like a film.

I saw my parents, brothers, sisters, my childhood, my wife and my four children, friends, the communities I served, NagyBanya and Satmar. I lifted my gaze to the heavens feeling that I was now the musaf sacrifice of Yom Kippur. With whatever strength still remained I shouted,

[Page 69]

“Ribono Shel Olam!”

In your Holy Torah, you wrote, “and you shall torture your souls.” But you also wrote,” and you shall take extreme care of your souls.” My dear Creator. Which of these should I fulfill? If I continue to fast it will be my end and then I won't be able to fulfill the other mitzvah. I repeated myself three times and then I added Ribono Shel Olam, this time I will fight You!

You don't let me fast, but I will fast! I believe I will succeed but grant me the strength to succeed! I felt terrible anguish in the depths of my spirit I had never experienced. I immediately felt G-d's answer, and felt my load had lightened. My hunger pangs disappeared and I felt renewed strength. I continued on, working for the Germans, and praying to G-d.

The afternoon passed quickly and easily. I prayed by heart in the afternoon and evening and the fast ended. We finished our work and started the seven-kilometer march to our camp. I saw not three, but three million stars in the sky, and I fasted for an additional hour in thanks to G-d. I took out my bread and fish and ate an hour after the end of Yom Kippur. “One who trusts G-d is surrounded by kindness.”

|

|

There are so many stories of Satmarers that it would take many more volumes to relate them all, so we shall tell only those that are most outstanding.

Dr. Julius Lass z”l, was the chief surgeon at Satmar's Jewish hospital. He graduated from a European medical school, but he received one another distinguished title. He was known as a “dog pig.” That was what he was called by his German supervisor.

The work moved quickly under the aegis of the Yank company in Wolfsberg. We dug ditches for water pipes. I worked next to Dr. Lass for many weeks. I knew him from Satmar and we became closer in the camp.

There was a high turnover among the cruel German foremen. One Monday morning our new foreman was “Old Terach.” This old man, who looked like a barbarian, walked through the fields where we worked wielding a long stick and beat us on our backs. Every day Terach chose a new victim upon whom to vent his anger.

One hot August day he appeared at our side and I knew that I was the victim of the day. I prepared myself for what lay ahead of me but to my surprise he pushed his stick into Dr. Lass' ribs. Dr. Lass wasn't even able to utter a moan before he heard the Nazi ask, “what do you do in civilian life?”

Dr. Lass removed his beret and stood at attention and answered. “Mr. Foreman, I answer you with humility, I am a physician.”

“You are a physician?” The monster shouted, and he beat Dr. Lass with his stick. “You are a dog pig,” he said, and continued the beatings. “And if you go back what are you?” Dr. Lass's face contorted with pain but he managed to reply, “Dear foreman, I tell you humbly that I am a dog pig.”

“Good, you answered well.” And he beat him again even harder than before. “Now listen! I will explain why you are a dog-pig.“ He told him that he brought his sick wife to a doctor. Even though he paid 300 marks to the doctor, she died three days later. Because of this all doctors are dog pigs. And he beat Dr. Lass again with his stick.

“Nu, did you forget what you are?”

Dr. Lass said, “Dear foreman, I speak humbly. All doctors are pig dogs, myself included.” The monster beat him again and then he patted him on his shoulder and said, “you answered well.”

Dr. Lass, who was a distinguished person, intelligent, respectful and kind, was insulted, beaten, humiliated by this inhuman primitive being. No wonder that this incident had an adverse affect on his already compromised health. He worked a few more weeks and then was hospitalized.

One evening during the intermediate days of Succoth he called for a few of his friends in order to say goodbye. He did not use words, but his eyes spoke for him. I asked, “Dear doctor, what is your name in Yiddish?”

He understood my thoughts and looked at me, his eyes tearing and his face radiating pain, “Moshe Yehiel ben Eliezer.” And so with a heavy heart we parted and that very night he passed away. May his memory be blessed.

Naftali Stern

Life and death may be controlled by the tongue. G-d sometimes helps a person when he puts words into his mouth which can determine his fate. The words that came out of my mouth determined my future.

It was the month of Shevat, February, in the late morning hours. We sealed the ditches we dug during the summer days. The cold winds of Sheliza tormented us, and we were unable to remain warm despite our attempts. “I was frustrated with my life,” said matriarch Rebekah. And that is how I felt about my life. My heart was bitter. I lost my will to live.

I measured the snow at 70 meters deep. I could not feel stones that could hurt me. I counted to three, and I threw myself backwards. I vocalized a loud sigh and a sound so strange that others nearby thought that I had died. The German foreman, the same Old Terach, decided that it was pointless to treat me. He'd throw me into a pit and cover me with dirt.

I decided I could stand being thrown into the pit - but being buried there? That was too much. My friends threw me in gently. I almost didn't feel it but I showed signs of life. Even the German realized that burying a living person was more than he was prepared to do. He pointed to two “dog-pigs,” ordering them to stay with me in the hospital which was 500 meters away from our work site.

The two who carried me turned out to be doctors from Satmar. Dr. Layosh Sharkani and Dr. Martin Meir stretched their hands out to create a seat for me. Others placed me on the “chair.” The rescue mission set off and I was unconscious through it all.

Dr. Meir said in Hungarian, “Oy poor guy, he's also gone. Slowly we're all going to go including the poor cantor. He kept us alive with his religious homilies and jokes.” That was how they eulogized me until we almost reached the hospital. All of a sudden I laughed. The two men carrying me were so shocked they almost dropped me. “What is it, Cantor, with you,” said Dr. Sharkani. “All three of us will be punished.”

I tried to calm them with my explanation. “Everyone who comes for a check-up is admitted to the hospital on the condition that he is running a temperature of at least 38.6, and I was not. If there was no fever, he got two slaps and a beating on the seat of his pants. I'll take the beatings myself, not you because you were ordered to take me. Don't be afraid.”

And now let us consider the gain. Today there will be a long line in the clinic and at least two and a half hours or more will pass before my turn. Isn't it worth it for me to take the slaps and the beating so that all three of us can enjoy the pleasant warmth of the clinic and a few hours without work?

The two doctors agreed that it was worth it and they felt great pity for me. Slowly we reached the waiting room. It was 8 am and we sat down on one of the benches enjoying the warmth. We let other more serious cases go before us so that when our turn came it was already around 11 am.

A high-ranking officer from the camp came into the clinic. The prisoners called him Shuster, shoemaker, because during the morning roll call he didn't pay attention to our torn clothing, our dirt, or our missing buttons, but he made a point to inspect our shoes.

When he came into the room he turned to me as if he were someone who knows medicine. He looked me over. “Nu, what is wrong with you? Are you a dog of heaven?” he asked. My two friends reported on my case, and the Shoemaker vanished briefly. He returned with a thermometer, told me to place it under my armpit and then left again. He didn't return for another half hour. I checked my temperature and I told my friend that the slaps and beatings would come because my temperature was 37 degrees. But it was all worth it because we were able to spend four hours in a warm room.

[Page 72]

Now I moved the thermometer from under my left arm thinking that that side was closer to the heater and would cause my temperature to rise. Forty-five minutes later the shoemaker returned and asked, “what is your temperature?” I slowly checked the thermometer and saw that it still said 37.

Feigning innocence, I said “Herr Komandant, my temperature is 74 degrees.”

The commander roared. “But how can that be? It's impossible.”

And with weak hand gestures I attempted to explain. “Before this it said 37 on my right side and then on my left size 37 again and all together that is 74.”

When the commander heard this his eyes widened and he yelled loudly. “Doctor, Doctor. Come quickly, urgent doctors' meeting.”

Three doctors, Dr. Steinberger from Beregsau, Dr. Koevary from Satmar, and Dr. Mannheim from Frankfurt, ran to me and then stood at attention for the commander. The Shoemaker told them what had happened and he waited for their medical opinions. All three doctors knew me well. They understood the game I was playing. They preferred to remain silent and so they left the decision in the hands of the shoemaker.

The commander was pleased with this and right away he lifted his hand and let out a loud laugh. “This is ridiculous. You stay in the hospital for as long as you need.” The doctors nodded in agreement and the two friends who carried me were very pleased. After all, they spent five hours in a heated room.

They must have told the other Jews at our worksite because that evening they all came to visit me. They blessed me and they asked how I was able to pull a fast one over such an “expert.” This is something unique to a Jew from Satmar.

I spent six weeks in my hospital bed. I was released in Adar when they evacuated the camp because of the approaching Soviets. This is how I got through the hardest period in the hospital. It could be that my answer, 74 degrees, was just a random utterance, but I am certain and I believe that Hashem placed these words in my mouth. Israel trusts in Hashem. Hashem is our aid and protector.

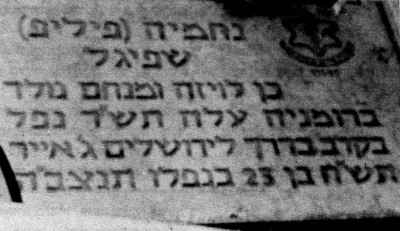

The Golden Album of the Hungarian Jewish war veterans is a treasure for the editors of this volume. During one of my visits to Rumania I acquired a copy which was a great help in my research. In it, I found 138 photographs of well-known Jews in Satmar. Sadly, none of them are still alive.

The Golden Album has great value for the Satmar community, as we are significantly delayed in publishing our memorial volume. This album can help us to overcome our delay. There are gaps in the album, but the stories, biographies and photographs in it remind us of many familiar Satmar faces who were in the Satmar ghetto, among them Karoly, Madiash, Varhol, and Herr Satmar. Families for whom no memory of their loved ones remains will be pleased to find these names in a photograph in the Hungarian part of the book.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Satu Mare, Romania

Satu Mare, Romania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 23 Nov 2022 by LA