[Page 44]

The Jewish community in Akkerman

from inception to destruction (cont'd)

On aid and welfare institutions

Kupat Milve Vechisachon (the Jewish Bank)

The fund was established in Akkerman after the 1905 pogrom and was known by the name, “Das Yiddishe Bankel” (the Jewish Bank). It played an important role in the rehabilitation of the Ukrainian refugees who decided to settle in the city, as well as in the rehabilitation of merchants and craftsmen affected by the economic crises that often plagued the region.

As told in the previous chapter, the businesses of many Jews were destroyed during the pogrom. Their property was destroyed, their source of livelihood was lost and their world darkened. An important Relief Society in Germany – the “Hilfsfareyn”– came to the aid of these unfortunates and sent urgent financial aid to all the victims of the pogroms in Russia and Bessarabia, including Akkerman. The immigrants from Akkerman to the United States felt the need to come to the aid of the victims and also sent considerable sums of money. At the same time the idea of setting up Kupat Milve Vechisachon [Loan and Saving Fund] began to develop.

This was not an original invention of the Jews of Akkerman. In 1898, a cooperative fund was established in Vilna and its name reached the cities of Bessarabia. Three years later, the first cooperative fund in Bessarabia was founded in Kishinev.

The committee, which dealt with the distribution of aid that came from outside, was left with a considerable sum of money, and when the question arose how to use this money, it was decided to establish in Akkerman a fund similar to those established in Vilna, Kishinev and other locations. On 8 August 1906, the fund was established and was among the first eight funds established in Bessarabia on cooperative basis. By 1929, another 33 funds had been established and their number had risen to 41. The fund in Akkerman was affiliated with the “General Cooperation Alliance in Bessarabia,” and thanks to a group of dedicated people to the fund (Hanna Gvirtzman, Yeshayahu Brudsky, the lawyer Serper, Michael Kruskin and others), it became one of most advanced and prosperous funds in Bessarabia. Every year a management was elected in secret and democratic elections. The annual meetings of the fund constituted a kind of an “exercise in democracy” for its participants. In meetings with a large number of participants, each member of the fund had the right to express his opinion, and since many exercised this right, sometimes the annual meetings lasted several nights. Among the candidates for the fund's management it was possible to find representatives from all strata of the Jewish population: merchants, people from the intelligentsia, artisans, Zionists, members of the “Kultur–Lige” and more, and the echoes of these meetings were heard in public many days after the date of the their gathering. It is worth noting the help that fund has provided to craftsmen for the purchase of tools, as well as to merchants for working capital in their business. One of the most important actions of the Cooperative Alliance in Bessarabia, after the First World War, apart from loans was the establishment of a mutual fund for deaths. These funds, according to their principles, were divided into three groups: “1) Payment to fund members according to the circumstances of deaths. The fund paid the heirs of the deceased a certain amount of this money – something that was customary in most funds. 2) Larger insurance payment for the death of elderly members and a fixed amount for the support of the deceased's family. 3) A fixed annual fee for all members and a fixed amount for the family of the deceased. The payment was – 200 leu for a year and the fixed support – 10,000 leu to the deceased family.” (from Yitzchak Hitron's article on the Jewish cooperation in Bessarabia).

Yeshayahu Brudsky and Hanna Gvirtzman were known in Bessarabia as experts in the field of cooperation and more than once lectured at national conventions. In 1931, a regional fund conference was held in Akkerman and was attended by 26 delegates, representing 10 funds.

The activists in the Akkerman's fund were: Hanna Gvirtzman, Yeshayahu Brudsky, Puntish Sharira, Dr. Michael Kruskin, the lawyer Serper, Dr. Yeshayahu Kogen, Leib Stambul, Baruch Gacht, Hirsh Brudsky, Zise Goldstein, Nathan Goldstein, A. Brenson, N. Stolbrod, Yakov Yashpon, Yakov Rabinowitch, Y. Schildkrauth, L. Risnzon, Mati Adlis, Mendel Arbit, David Wisser, Mani Yaroslavsky. Perldansky, Hanna Zef, Dali Palikov, Gertz Abramowitch, and others.

The fund received a lot of help from the organization of former residents of Akkerman in the United States which occasionally transferred monetary allowance to the fund.

The community's Kupat Gemilut Hassdim

After the First World War Kupat Gemilut Hassdim, which was initiated and managed by local activists, was liquidated. Indeed, the cooperative financial institution Kupat Milve Vechisachon existed, but it was a financial–banking institution subject to a procedure that required guarantees from all those in need of a loan and not everyone could afford it. There was a noticeable lack of a public institution that would give loans to the needy on more favorable terms. The community committee felt this shortage and in 1925 established Kupat Gemilut Hassdim with a based capital of 12,000 leu.

[Page 45]

We learn about the development of this institution from an article in the newspaper “Unzer Tsayt” [“Our Time”] from 1928 signed by Y.S. It tells that there was already 260,000 leu in Kupat Gemilut Hassdim and the fund distributes loans to the needy in the amount of 2,000 leu each. The significant increase in the fund's capital comes thanks to donations from former residents of Akkerman in the United States, as well as donations from local people.

During various periods of distress in Akkerman, many Jews who engaged in small–scale trade and handicrafts survived the economic holocaust thanks to the fund's loans. It is worth noting that most of the Jews who needed fund's grace repaid their loans as soon as possible.

|

|

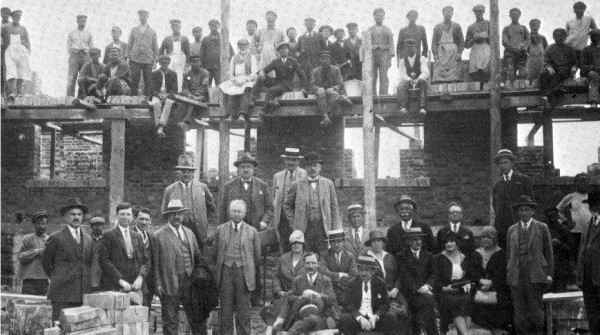

The public committee for the construction of the new hospital and the Women's Committee

Photographed next to the hospital during construction in 1929

Standing right to left: B.L. Prelis, Y. S. Serper

Seating right to left: Mrs. Agol, Mrs. Einbinder, Dr. Kruskin, Mrs. Sirotin, Dr. Kogen, Dr. A. Schwartzman, Dr. S. Zerling, unidentified

Standing: Y.B. Brudski, Dr. Y. Feldstein, Nachman Stolbrod, Florence the construction supervisor, Leib Stambul

Behind them standing (right to left): Hanna Zef, the dentist Agol, the contractor Koskov, M. B. Adlis. Further up: M. G. Milstein, Y. Kvitko, A. Sirotin, M. Helman

On the scaffolding – the builders |

|

|

| “Ort” school for girls for the sewing profession |

[Pages 46-47]

|

|

The local “Keren haYesod” committee with the delegation from the center, 1924

Sitting, right to left: Moshe Helman, Meir Starec, Yisrael Skoriski (delegation member), Yakov Berger, Dr. Spir (head of the delegation), Moshe Milstein, Shmaryaho Segel (delegation member), Dr. S. Zerling

Standing, right to left: Baruch Geret, S. Sternsaus, Wolf Gordon, Zise Gladstein, Alyakom Kaplansky, Yosef Aharonovich, Leib Stambul, Yosef Serper, Yosef Rivkin |

|

|

| “Tipat Halav” of “OZE” society – dairy kitchen for children aged two to six, 1929–1928 |

[Page 48]

|

|

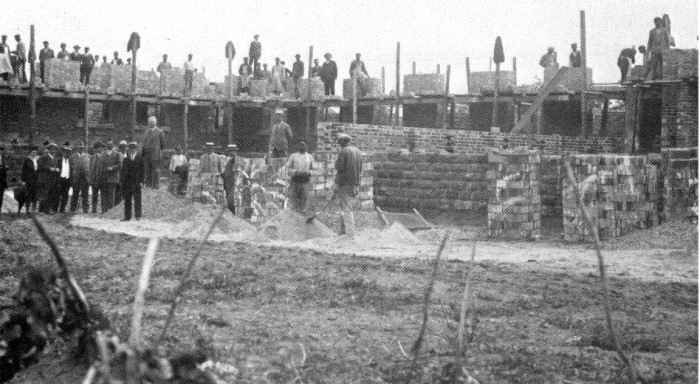

The public committee for the construction of the New Hospital

Seating first row right to left: Dr. A. Schwartzman, Dr. Y. Feldstein, A. Sirotin, M. Milstein, M. Kruskin, Anna Sirotin, Bina Feldstein

Standing second row: Leib Stambul, Yisrael Kushnir, Moshe Helman, Shmuel Berger, Mendel Gelman (slaughterer), Baruch Gacht, Yosef Serper, Yosef Kvitko, Musi Gvirtzman, Dora Goldman

Standing third row: David Brand, Nachman Stolbrod, Avraham Krolik, Hersh Blinder, S. Prelis, M. Edlis, Hanna Krolik |

|

|

| The Jewish Hospital under construction (back side) |

[Page 49]

“Maot Chitim” – “Kamcha Depasha”

To the credit of the Jewish community of Akkerman must also be attributed the monopoly it had for baking matzot for Passover. The community did not allow any institution, or a private person, to bake matzot and took all legal measures against attempts made to bake private matzot. The profit belonged to the entire public, because every rich matzot buyer was required to pay “Maot Chitim” [“Wheat Money”] so that also the poor will be able to get matzot for Passover free of charge. It is worth emphasizing that they did not refuse, or evade, and even the assimilated and those far removed from religious tradition, observed this mitzvah. The group of porters, who brought the matzot from the bakery to the homes of rich customers, also brought the matzot to the homes of the poor so as not to embarrass those who did not pay. The community also provided the city poor with potatoes and wine for the four glasses. And so Schildkrauth writes in his book: “Rich and poor, without distinction, ate in Akkerman the same delicious matzot that were baked together. The poorest homeowner, who received the free distribution from “Maot Chitim” fund, received the same thin bright–white matzot – as the rich homeowner who donated his greatest contribution to “Maot Chitim.” In this respect, Akkerman was among the few Jewish settlements in Bessarabia who observed the mitzvah of “Kamcha Depash” [flour for Passover] in this way.

“OZE”

This institution, which began its blessed activities even before the First World War, also contributed to the medical needs of the Jewish population. It was especially effective in the hospitalization of children and pregnant women. In “OZE” [Obschestvo Zdravookhraneniia Evreev – Organization for the health protection of Jews] it was possible to get free fish oil for poor children and medicines. The branch also served as “Tipat Halav” institution [“A Drop of Milk” – preventative medical services for mothers and infants].

“OZE” clinic was equipped with an X – ray machine, quartz lamps and diathermy, which were purchased thanks to a donation from M. Karalik. The active philanthropist, Dr. Shapira, stood at the head of “OZE” and the institution's activists were: Dr. Kogen, Dr. Zerling, Dr. S. Itzkovitz, and also Y. Brudsky, M. Kruskin, Yitzchak Feldstein, Alexander Shapira, Dr. E. Wilkomirski, Hanna Karalik, M. Yaroslavsky, Berta Fildman. The secretary was Y. Schildkrauth.

“OZE” not only provided medical assistance, but also conducted an information campaign regarding the preservation of the health of the Jewish population. In the newspaper “Unzer Tsayt” from 6 November 1927 it is told that the local “OZE” committee conducted “a week of health.” On the first day of Sukkot, Dr. Kogen, Dr. Zerling, Y. Brudsky, Y. Serper and others, appeared at the synagogue and explained the duties of “OZE” and ways of maintaining a person's health. The doctors also talked to the students of “Tarbut” and Talmud Torah schools about the duties of “OZE” and information leaflets were distributed to the homes.

“ORT”

This institution was also established before the First World War but did not have its own school. At that time its role was limited to conducting craft classes and operating a small carpentry shop under the management of the carpenter, Chaim Britva. Later, a school was opened and its administration was composed of Berel Roitman, Leib Stambul, Nachman Stolbrod, Chaim Britva and others. They made considerable efforts to promote and improve this institution, but due to lack of financial means they were unable to establish additional departments. In the newspaper “Unzer Tsayt” from 27.3.29, in an article signed by “Anakermaner” we read:

“In the city of Akkerman that its total population reaches to 25,000 people, there are 10,000 Jews and about 300 families earn a living from craft. The rest make a living from trading grain, small trade, brokerage, etc. The trade collapsed due to the dire economic situation and many are the Jews who walk idle and reached the point of starvation. Because of the economic situation, many non–Jewish boys, and peasants, began to learn crafts and posed a serious danger to the continued existence of the craft industries on the Jewish street. Therefore, a large meeting was called with the participation of the representative of “ORT” center in Bessarabia and the agronomist, Haim Feigin, who addressed the gathering. The hall was full to capacity, not only with craftsmen but also with Jews from the various strata of the population. The speaker warned of the situation in the country and encouraged the Jews to send their sons to learn a trade. He also promised, on behalf of the center, financial support for the opening of new departments at the “ORT” vocational school.

However, the promised help they had hoped for did not arrive and the school did not progress satisfactorily.

[Page 50]

|

|

| Free kitchen for children in the famine year 1929 with the women's committee |

|

|

The first management of “Kupat Gemilut Hassdim” in Akkerman, 1907

Sitting right to left: Yakov Sidikman, Dr. Y. Shapira, Ravutski, Ben–Zion Cohen, Y. Yishpon, M. Kruskin

Standing: Elisha Brenson, Shmuel Glefend, Hanna Gvirtzman, I. Vladimirovich Brudsky, Nathan Goldstein, Felik Preladenski, Y. Einbinder |

[Page 51]

The Jewish Hospital

The old Jewish hospital in Akkerman was established in 1882. The hospital building on Izmailovsky Street belonged to the philanthropist Dr. Korean. It was an old building with two–room, one for men and one for women, and the total number of beds was twenty. It was overcrowded and the sanitary conditions were poor. Despite the difficult conditions, this hospital played an important role, especially for poor Jews who needed it. The chief doctor, Dr. Y. Shapira, was the living spirit in the hospital. He devoted much time and effort to it and everything was done voluntarily. In 1924, Akivah Margolin, member of the Society of Emigrants from Akkerman in the United States, visited Akkerman. In view of the poor conditions of the hospital he encouraged the community council to purchase a plot of land and plan a new hospital, and undertook to raise the necessary financial means for the building from the former residents of Akkerman in the United States. The committee, which was elected for the construction of the new hospital, opened a fundraiser for this purpose among the city residents and the plot of land needed for the building was donated by Dr. Kogen. From 1925 to 1932, the Society of Emigrants from Akkerman in the United States transferred about 50,000 dollars for the needs of the building and the equipment for the hospital. In addition to this, there was also a significant contribution from Maxim Karalik, a native of Akkerman who lived in the United States. The construction of the hospital lasted seven years and on 7 October, 1934, the hospital was officially opened in an impressive ceremony in the presence of many of the city's residents and representatives of the authorities. The new hospital had 14 rooms and 60 beds, its annual budget reached 100,000 leu, and the medical staff included specialist physicians and experienced nurses. The level of the hospital was generally appreciated by the Jewish and the city's Christian residents who also needed its good services.

Home for the aged

This institution, like other charities, has always been in financial distress, but served as an only address for the elderly who had no other address in old age. The person who got this institution out of the constant state of distress was, as stated in Schildkrauth's book – “A tireless stubborn old man, R' Simcha Bronstein, did not rest and worked hard until he obtained financial means and erected a new building for the Home for the aged. Mrs. Perlis, together with R' Simcha Bronstein, took care of the proper maintenance, sanitary, health and financial means of this important institution.”

|

|

Farewell party for Akivah Margolin, member of the committee of former residents of Akkerman in New–York, 1924

Seating from the right: the first two unknown, Hanna Gvirtzman, Mrs. Gvirtzman, unknown, Y. Berger, Shmuel Trackman, Mrs. and Akivah Margolin, Zev Krushkin, Yosef Rivkin, Nathan Goldstein, Shabtai Novak

Standing from the right in two rows: Zise Gladstein, R' Shmuel Berger, Mendel Arbit, Mrs. Moskowitz, Pinchas Milman, the cantor Moshe Cohen, Hersh Brudsky, R' David Braner, Felik Berg, R' Simcha Bronstein, Meir Obet, Hersh Blinder, R' Mendel Gilman (slaughterer) A.V. Brudsky, R' Haim Kaminker, Dr. Y. Kogen, Yakov Brand, Y. Yashpon, Mrs. Fidelman, Mrs. Zipa Berg, Mrs. Perlis, Berel Moskowitz, Yitzchak Arbit, Meir Starec, Shmuel Gelfand, the rest unknown. |

[Page 52]

|

|

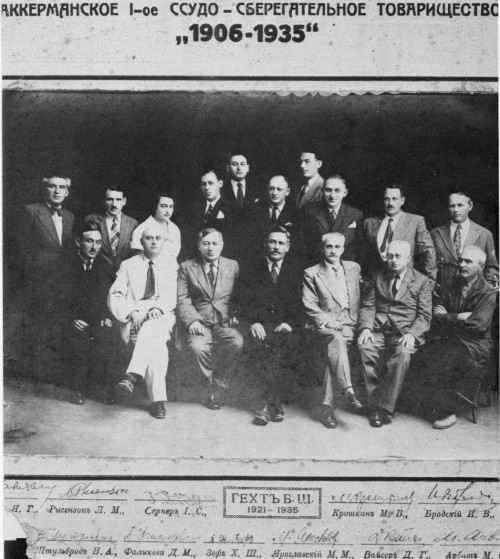

The management of “Kupat Milve Vechisachon” with Baruch Gecht ( board member), prior to his immigration to Israel in 1935

Seating right to left: H. Brudsky, Y. Brudsky, Krushkin, B. Gecht, Y. Serper, Risnzon

Standing: M. Adlis, M. Arbit, D. Weisser, Grez Abramowitch, M. Yaroslavsky, Freldensky, H. Zef, D. Falikov, N. Stolbrod, S. Perlis |

[Page 53]

Public activists in the Jewish community of Akkerman and its various institutions and Zionist activists in the 1920s and 1930s until 1940

Chairmen of the community:

Dr. Shapira Yitzchak – first chairman

Hanna Gvirtzman – second chairman

Goldstein Nathan – third chairman

Milstein Moshe – fourth chairman

Helman Moshe – fifth and last chairman

Vice chairmen served at different times:

Berger Yakov

The lawyer Serper Yakov

Dr. Y. Kogen (Kultur–Lige)

Activists in the community and its institutions and Zionist activists:

Abramowitch Grez

Einbinder

Arbit Yitzchak

Blinder Hersh

Berg Felik

Brudsky A.V.

Brudsky Tzvi

Bronstein Simcha

Brend David

Gecht Baruch

Gladstein Zise

Gelman Mendel, ritual slaughterer

Helman Aba

Zef Hanna (Kultur–Lige)

Trahtman Avraham

Yaroslavsky Muni

Cohen Moshe

Manueli Tzvi

Stambul Leib

Starec Meir

Dr. Feldstein Yitzchak

Perlis S.

Dr. Zerling Shaul

Kushnir Yisrael

Krushkin

Rabinowitch Yakov

Risenson

Schildkrauth Yisrael

Sternsaus Shmuel

Stolbrod Nachman

Shapira Alexander

[Page 54]

The Zionist movement in Akkerman, 1917 to 1941

The 1917 revolution, and the liberation of Russia from the Tsar's yoke, raised many hopes among the Jews of Bessarabia. There was a general feeling that they were on the verge of a new era, of freedom and the unloading of the yoke of bondage, a kind of a new “spring for the nations.” The Jews of Akkerman, of course, were also among the harbingers of the end and the dreamers of the pink dreams.

Long before the great revolution, on 21 March 1917, the Revolutionary Provisional Government issued a proclamation announcing the abolition of all religious, national and political restrictions. It was natural that the national awakening among all nationalities of “Mother Russia” did not skip the Jewish national minority. The only movement that showed understanding for the current problems, and the dynamism required by the political changes in Russia – was the Zionist movement that under its flag gathered many who saw the solution to the Jewish problem in the renewal of Jewish independence in Eretz Yisrael.

In March 1917, the Odessa Zionist Committee to which the Zionists of Bessarabia were also subordinate, published a proclamation signed by Menachem Ussishkin, and so it was said among others: “Great events have taken place, bright chances for freedom and a life of happiness are opening up before all the people living on the land of vast Russia. Luck has finally begun to brighten the face of our suffering nation, and now it will stand up straight and cease to be a tortured stepchild.” This proclamation did not fall on deaf ears also in Akkerman. Important homeowners in the city searched and found the way to the Zionist movement: Moshe Helman, Dr. Shaul Zerling, Miriam and Yitzchak Feldstein, the cantor Avraham Gotlib, Shmuel Sternsaus, the cantor Moshe Kogen, Dani Harol, P. Berkov, Rabinowitch, B. Hacham, K. Tabachnik, the brothers H. and Y. Karaninsky, Y. Schildkrauth, Z. Manueli and others. Zionist conferences were now held in public and openly, in cinemas and synagogues, and there was no need for camouflage although there were also those who feared the Gentiles' evil eye at the sight of this preparation in the Jewish public. Y. Schildkrauth tells that after the outbreak of the revolution, Akkerman prepared for a large demonstration accompanied by an orchestra, flags, and slogans calling for support for the revolutionary government. A group of Zionists planned to demonstrate with a Jewish national flag at the head of the procession, but there was another group who opposed it for fear that it might harm the Jews. And so Schildkrauth is telling: “They made a double–sided blue and white velvet flag, in the middle it was decorated with a large “Star of David” embroidered in gold, its rim was triangular, its thighs embroidered with gold and silver threads, and at its two sharp ends hung two gold tassels. The flag was hung on a long oak pole painted in brown lacquer and a silver “Star of David” was stuck in its head.”

On the day intended for the demonstration the Zionists gathered in the synagogue courtyard to accompany the protesters from there. At the same time, a group of Zionists argued and flew into a rage over the question of the flag and could not reach a decision on whether to take responsibility for possible events. Then, what happened happened – at the height of the rage and quarrel, Ozer Feigin, the tall and wide, separated from the arguing group without the others noticing him. He grabbed Samet's blue and white flag, which was hung on a long oak pole, and before they had the time to give their opinion on this, he hurried forward as he was carrying the large heavy flag in front of him with his strong hands. The angry and furious group stood stunned… but they quickly shook off and began to chase after R' Ozer Feigin who ran with the flag… and so, while running, they joined the street demonstration together.”

Later in this “spicy” description Schildkrauth is telling, the national Jewish flag was received with cheers by the Ukrainian group that also carried its national flag, and many Jews gathered around the national flag, which was carried high in Ozer Feigin hands, and no harm came to the Jewish demonstrators.

At the Seventh Zionist Conference held in St. Petersburg in June 1917, M. Starec and Y. Karaninsky participated as delegates from Akkerman (12 delegates from Bessarabia participated in this conference). When they returned from the conference they reported its action to Akkerman's Zionists.

In November 1917, after the Balfour Declaration, a wave of national–Zionist enthusiasm passed among the Jews of Akkerman. Eyewitnesses say that in the various assemblies, held in synagogues and public halls, they felt the great admiration of the masses of Jews who saw in this declaration the real end of exile. Rumors and legends spread in the city about ships standing ready in the port of Odessa to transport Jews to Eretz Yisrael. It was soon proved that these were nothing but false rumors and the stormy emotions cooled a little. The people, who were full of suffering and distress, tended to such rumors and hoped that redemption would come one day. This alone provided fertile ground for those who spread rumors of various kinds.

Indeed, ships did not wait at the port of Odessa, but, on the other hand, a group of young people who did not wait for miracles and did not rely on miracles, decided to pave their way to Eretz Yisrael. They were not members of a youth movement, and did not receive training in “HeHalutz,” but the love of the country and the vision of redemption burn in their hearts, and they did not shy away from difficulties and mishaps. They were: Yeshayahu Botoshansky, Aharon Brand, Yehusua Berger, P. Berkov, Avraham (Kafri) Dorfman, Avraham Molodowsky, Avraham Margalit, Serper, Noah Zukerman, Aharon Kaminker from Shabo and Yisrael Rabinowitch. This first group from Akkerman immigrated to Eretz Yisrael where there was no organizational body to absorb them. Without knowing what and who was waiting for them in Israel, they got up and emigrated.

[Page 55]

Sometime later, there was an attempt to organize a group of local young women for training for a working life in Eretz Yisrael. They leased a plot of land, grow vegetables and sold them at the local market. This attempt did not last long but a few young women immigrated later to Eretz Yisrael.

In the first all–Bessarabia conference, which was held on 4–8 May 1920, eight delegates participated from Akkerman: M. Starec, Yakov Berger, Dani Harol, P. Berkov, B. Hacham (later moved to Tarutino), Julius (Yehudah) Danovich, Yisrael Rabinowitch and Kuma Tabachnik. At this conference the discussions revolved around the questions of the ways of building the country, the forms of settlement and the ways of organizing the Zionist organization in Bessarabia. The debates were mainly between the General Zionists and Tzeirei Zion. According to what is told in David Vinitzky book, “Bessarabia He–yehudit Be–ma'aroteha” [The Jews in Bessarabia between the World Wars 1914–1940], Y. Danowitch and Avraham B. Hacham from Akkerman participated in this debate. They raised their concerns that the Jewish worker in Israel will be exploited by their wealthy employer, demanded that the country be built on the foundations of justice, criticized the private investment and obliged it to set aside a percentage of the profits for the benefit of the workers. In the early 1920s, Yuly Danowitch was a member of the HeHalutz center in Bessarabia.

With the annexation of Bessarabia to Romania in 1918, the Jewish public, especially the Zionist, was cut off from its center (Odessa) before establishing central institutions that would direct public and Zionist activity in the countryside. The above conference – the all–Bessarabia – gave its opinion on this, chose institutions, and organized the Zionist activities as well as the activities for the Zionist funds.

The activity for the funds

The collection of donations for Keren Kayemet, Keren Hayesod, HeHalutz and “Tarbut” funds was conducted with the approval of the Romanian authorities, and the Jews of Akkerman responded generously. The blue boxes of Keren Kayemet [Jewish National Fund] were at the homes of many Jews and the Zionist activists were busy emptying the boxes. Only after the Zionist youth movements were established this role was transferred to them. The fundraising for Keren Hayesod [The Foundation Fund] was carried out with the help of key activists, or emissaries from Israel who walked from house to house together with the local activists and raise funds. It is worth noting, that even in times of economic crisis and distress – and of course there was no shortage of them – Akkerman Zionists contributed willingly, each person to his ability. Some examples may validate our words. In 5698, which was a year of a difficult economic crisis, the sum of 13,924 Leu was collected in Akkerman for Keren Kayemet, while in 5699 the sum of 347,924 leu was collected for Keren Kayemet and the fundraiser campaign for “Hagelila” of Keren Hayesod. According to the size of the donations, Akkerman was in third place in Bessarabia, although according to the size of the Jewish population it was in ninth place. We also know that in HeHalutz week in 5687, 19,450 leu was collected in Akkerman and again it took third place in Bessarabia.

In the meeting of the first immigrants from Akkerman, which took place in Tel Aviv for the needs of this book, Noah Zukerman told about everything that preceded their immigration, and here is a summary of his words:

“I was not a member of any Zionist movement or youth movement. What motivated me to immigrate to Eretz Yisrael was the education I received at home and especially the great Zionist awakening that was felt in Akkerman after the Balfour Declaration. I still remember the big meeting held at the synagogue to mark the Balfour Declaration. The enthusiasm of the speakers reached its peak and swept the large audience as well. The speakers were Yisrael Rabinowitch, Meir Starec, Janowitz, and maybe someone else. I applied for a passport so that I could travel to Eretz Yisrael, but in the meantime I was drafted into the army and served for three months. At the end of August we were given a holiday to help the farms that needed working hands, and when I came home for a holiday I found the passport. I decided to leave as soon as possible. Yakov Berger gave me a recommendation for the Zionist organization in Bucharest where I obtained my visa to Constantinople. For travel expenses my father gave me 1,000 leu, my brother 1,500, my brother–in–law Yakov Rabinowitch an amount that I cannot remember. In any case, the money I had was enough for a stay of ten days in Constantinople with my friends Aharon Kaminker.”

In the years 1927–1928, when the gates of Israel was closed, a group of 30–40 Jews members of the middle class who wanted to immigrate to Eretz Yisrael, was organized in Akkerman. In this group were small merchants, craftsmen, brokers etc. The majority were elderly families who could not reach Israel through the pioneering movement, and could not even obtain certificates by official means. This book tells about what happened to this group and we will not talk about it here, but it is worth emphasizing that the Zionists in Akkerman never reconciled with the decrees of immigration and sought every possible way to reach Israel, even through Cyprus, as this middle–class group has tried. Baruch Ghent headed this group.

[Page 56]

We do not have in our hands exact statistics on the number of Jews who immigrated from Akkerman to Eretz Yisrael, but there is a basis for the assumption that more than four hundred people immigrated by the outbreak of the World War.

The connections between the immigrants from Akkerman in Israel with the families who remained in Akkerman were very tight, but they were family ties that were expressed in private letters without any pretenses. Only once, to the best of our knowledge, these ties deviate from the usual course and received a kind of political mission. It was in July of 1935, when a proclamation was distributed in Akkerman towards the elections ahead of the Zionist Congress. It was addressed to “fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters, friends and members” and signed by former residents of Akkerman in Eretz Yisrael. The proclamation opens with an expression of gratitude to the Zionists in Akkerman who voted in the previous congressional elections for the Working Land of Israel list, and continues with the summaries of the achievements between congress and congress, with the conclusion being: “Vote for the List of the Working Land of Israel”

The following are the names of the signatories to this proclamation:

| Shmuel Zukerman – Tel Aviv |

Eliyahu Margalit – Kfar Gibton |

| Moshe Chaim Margalit – Rehovot |

Binyamin Hirschfield – Kvozat Gordonia “Bezor– Netaim |

| Manos Freida – Kvozat Hasharon |

Bruria Schwartzman – Karkur |

| Leah Berger – Rehovot |

Nachum Liber – Tel Aviv |

| Ancel |

Nissan Stambul – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

| Hinda Durpman – Tel Aviv |

Yochevd Shapira – Jerusalem |

| Enya Malchin – Haifa |

Aharon Dorfman– Tel Aviv |

| Yehezkel Manos – Kvozat Hasharon |

Elisha Bedgi – Netanya |

| Nesia Zukerman – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

Avraham Cornbleet – Ra'anana |

| Frima Zeider – Netanya |

Miriam Gordon – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

| Leah Neiman – Kineret |

Feibush Cohen – Hadera |

| Avraham Neiman – Kineret |

Bast – Tel Aviv |

| Nachum Liber – Tel Aviv |

Yochevd Shapira – Jerusalem |

| Kunicher |

Shmunis – Hadera |

| Shlomo Gecht – Haifa |

Aharon Kaminker – Tel Aviv |

| Sonia Margalit – Rehovot |

Zipora Edlis – Tel Aviv |

| Zipora Margalit – Even Yehudah |

Yochevd Shapira – Jerusalem |

| Rivka Cohen – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

Ester Lapida – Haifa |

| David Malkin – Kibbutz Hashomer Hatzair – Ein Hai |

Yehusua Berger – Pardes Hanna |

| Aharon Brend – Tel Aviv |

Zarna Molodowsky – Tel Aviv |

| Yisrael Manos – Mikveh Yisrael |

Baruch Cohen – Kvozat “Avoka” – Pardes Hanna |

| Klara Licht – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

Avraham Molodowsky – Tel Aviv |

| Efraim Durpman – Tel Aviv |

Eliyahu Lev – Haifa |

| Rachel Goldberg – Kfar Saba |

Sara Gelman – Afula |

| Yosef Glikman – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

Niuma Kurin – Petach Tikva |

| Shlomo Buloshin – Petach Tikva |

Zvi Misonzik – Kibbutz Hashomer Hatzair – Magdiel |

| Maliya Gordion – Ramat Gan |

Yehusua Botoshansky |

| Avraham Dorfman – Tel Mond |

Zilia Gerber – Netanya |

| Mendel Margalit – Rehovot |

Avigdor Risenzon – Tel Aviv |

| Sara Manos – Kvozat Hasharon |

Avraham Margalit– Binyamina |

| Reuven Manos – Kfar Haim |

Mora Failand – Netanya |

| Yosef Chaplin – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

Enia Malchin – Haifa |

| Chana Dorfman – Tel Aviv |

Noah Zukerman – Tel Mond |

| Yakov Yacobson – Kvozat “Bezor – Netaim |

Rivka Manos – Netanya |

| Leah Berkowitz – Tel Aviv |

Yehezkel Manos – Kvozat Hasharon |

| Shmuel Stetsky – Netanya |

Elisha Bedgi – Netanya |

| Nechama Kagalsky – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

Yitzchak Toyerman – Petach Tikva |

| Aba Biranbaum – Kvozat “Avoka” – Pardes Hanna |

Frima Zeider – Netanya |

| Rivka Yitsḳovits – Hadera |

Sonia Margalit – Rehovot |

| Frida Lederman – Kineret |

Miriam Gordon – Kvozat Mesada – Hadera |

| Michael Shainer – Netanya |

Feibush Cohen – Hadera |

| Chava Dorfman – Tel Aviv |

Botoshansky Shifra – Hadera |

| Yehusua Bvolovitz – Hadera |

|

[Page 57]

The library as a factor in Zionist education

There is no doubt that the public library was an important factor in the Zionist education systems provided to Jewish youth in Akkerman, and it is worth noting in detail the role it played. It was founded in 1917 by “Tarbut” society and two activists who dedicated the best of their time to it: Moshe Schildkrauth and Kumi Tabachnik, who collected books and donations for the library. The library was housed in two rooms on Moskovskaya Street and, in fact, was the first Jewish public library in the city. However, the two rooms were not only used to exchange books, but constituted a Zionist center. Almost all the Zionist activity in the city was concentrated within the walls of these rooms, the meetings of the funds committees, “HeHalutz,” and also the committees of the parties that already existed at that time. Moreover, the first Hebrew kindergarten was also opened in the library rooms. Over time, rehearsals of “Hazamir” choir conducted by Cantor Moshe Kogen, rehearsals for parties and balls, and meetings of the circle “Speak Hebrew” were also held there.

After the death of Moshe Schildkrauth and Kumi Tabachnik, both died at a young age, the teacher Shmuel Sternsaus took on himself the management of the library. S. Geber wrote in this book about his dedication to this role. It is worth noting, that the readership in the library has grown considerably and “Tarbut” school provided the majority of readers since many students were helped in their studies by books from the library. Mr. Sternsaus took special care to enrich the section of reference books in the library, and with the development of the youth movements in the city saw a need to order many books that the counselors of the various youth movements can be assisted by them.

The library's two rooms bordered the rooms of “Kupat Milve Vechisachon” and belonged to it. In an article published in “Unzer Tsayt” we read an article under the title “A scandal related to the public library” and so it is said in it: “Kupat Milve Vechisachon” wanted to take part of the library space to expand its residence. On Saturday, a hole was opened in the wall shared by the library and the fund to annex part of the library area to the fund. The library management arrived on time and plugged the hole. At the meeting of the fund members a scandal broke out on this issue and it was decided not to touch or take over the area of the library (signed on the article – Y. Schildkrauth). The library remained unchanged until the entry of the Soviets to Akkerman in 1940.

“Tarbut” society and “Tarbut” school

The crown glory of the Jews of Akkerman in general, and the Zionist movement in particular, was – “Tarbut” and the chain of its achievement: kindergarten, the Hebrew school and the gymnasium. Certainly, “Tarbut” would not have been founded without the help of a group of activists from all parties, but there is no doubt that Yakov Berger deserves all the praise. He knew how to cooperate with all the activists and with all the streams and marched “Tarbut” to the achievements it had reached.

Unlike other cities in Romania and Bessarabia, in which “battles” broke out between Yiddish and Hebrew fans for the place of one language or another in schools, there were no such struggles in Akkerman. When every national minority was given permission to develop its educational institutions, and to cultivate its language in these institutions, the assumption accepted by almost everyone in Akkerman was: Hebrew is the main language of instruction in Jewish schools.

|

|

| The kindergarten of the Hebrew gymnasium, 1919 |

[Page 58]

Yiddish was the language of instruction only in “Talmud Torah,” whereas in the first kindergarten of “Aunt Manya” and “Aunt Shoshana,” and in the elementary school – Hebrew was the dominated language. The Romanians did not care. They were interested to push out the influence of the Russian language and the Russian culture, and they did not care with what language this would be done. Only a few years later, when the Romanians established themselves in Bessarabia, they began to narrow the steps of the Jewish educational institutions.

Many of former “Tarbut” students brought up in this book memories and experiences from their school days at “Tarbut” and praised their principal and the teaching staff, but it is worth emphasizing that the parents should also be praised. They sent their children to the Hebrew school despite the high tuition that the children of the affluent classes had to pay to enable the children of the poor to study in “Tarbut.” Therefore, it was a commendable mutual aid.

It is interesting that schools, in which the language of instruction was Yiddish, disappeared in the course of time in Bessarabia, and even that under the pressure of the parents who preferred Hebrew over Yiddish. D. Vinitzky tells in his book “Bessarabia he–yehudit be–ma'aroteha” [The Jews in Bessarabia between the World Wars 1914–1940] that in the nationalized state gymnasium (No. 4) in Kishinev, whose language of instruction was Yiddish, a survey was held in May 1920 among the students' parents on behalf of the Board of Education. The parents were asked what language they would like as a language of instruction for their children. It turns out that out of 103 questioned, 92 answered that they prefer Hebrew and only two preferred Yiddish as the language of instruction. This survey indicates the mood on the Jewish street in Bessarabia, and Akkerman was no exception. The Hebrew language was generally seen as a wedge against assimilation' and, as already mentioned, the religious circles also preferred the Hebrew language as the language of instruction. No wonder many parents, who were far from Zionism or even hostile to it, became Zionists thanks to their children who attended the Hebrew school. There were, indeed, quite a few in Akkerman who sent their children to study in Romanian government schools but no ideological reasons motivated them to do so, just the benefit of it. Apart from the low tuition at the government schools, the education authorities have made it easier for the graduates to be admitted to Romanian universities, which was not the case for the graduates of other schools who had to pass supplementary government exams that were not at all easy.

Despite the reliefs, not many parents were tempted to the charm of the Romanian schools and have done their best so that their sons would be able to finish the Hebrew gymnasium.

Many praised the level of education in gymnasia “Tarbut” in Akkerman, but we also came across expressions of certain criticism. In an article in “Unzer Tsayt” from 7 December 1922, Yosef Ben–Daniel writes: “Tarbut” in Akkerman has a good kindergarten and a gymnasium, and thirty percent of the students study for free, but “Tarbut” committee conducts its work in a way that is too “family oriented” and during the four years of the committee's existence not a single general meeting has been convened.”

|

|

The gymnasium principle, Y. Berger, with the teaching staff in 1928

Seating right to left: S. Sternsaus, S. Helman–Sofer, Y. Berger, M.Y. Berman. Standing: B. Finchlet, S. Zukerman, Neami (secretary), the cantor M. Kogen, M. Starec, S. Zernivski |

[Page 59]

In the book mentioned above by Vinitzky the budget of “Tarbut” (including one kindergarten class, four elementary school classes and seven gymnasium classes) is published. In the year 1931–32, it reached the sum of 900,000 leu. The budget is calculated on a total of 200 students. The institution was facing deficits, and if not for the balls and fundraising campaigns that “Tarbut” activists held every year to cover the deficits, “Tarbut” institutions would not have been able to complete a single school year.

As mentioned, a few years later the Romanian authorities began to harass the Jewish educational institutions. And so we read in an article signed by “A Feter” (father) in “Unzer Tsayt” from 23.9.1929: “On Purim an administrative order arrived that requires the closure of the elementary school next to the gymnasium after nine years of existence. The director of the gymnasium, Y. Berger, immediately went to the appropriate institutions and managed to repeal the decree and open the school. The Jewish public opinion calmed down as they were confident that the order, on behalf of the central institutions, would also bind the local school superintendent. But it turned out that the supervisor did not take this into account, he managed to carry the matter for another week and canceled the studies of hundreds of children. Who knows how long the matter would have lasted if it had not been for the district superintendent, Bogdan, who was sent specifically by the education authorities to Akkerman to settle the matter and reopen the school.”

Apparently that same government supervisor of education was a malignant thorn in regarding the school in Akkerman, since three months later (20.6.1929) another article was published in “Unzer Tsayt” and in it an expression of regret that the same supervisor, who was harassing the Hebrew gymnasium, has not yet been replaced and he does not respond to the teachers' requests regarding the end–of–year exams by the authorities. “We hoped – it was said in the article – that the same official would be fired but we were disappointed. After great efforts we were able to influence him to keep the teacher Tsheki away from the examining committee. The superintendent does not agree that the students of “Tarbut” school will take the final exams at the school itself, they are sent to be tested at the public school in Artsyz, and required to pay 800 leu for a test of one class and 1,600 leu for two classes.” Even if the intent of these lines is not clear enough, it can be concluded from these two articles that the local Romanian Education Authority did not take kindly to the development of “Tarbut” institutions and harassed them with various excuses. It is difficult to assume that this harassment was not with the approval of the central education authorities, but it did not stop the development of “Tarbut” institutions. It must have increased the national consciousness of the Jews in general, and of the Zionist youth in particular, who realized that equal rights in Romania for Jews is a daydream.

*

Sources and Bibliography

Encyclopaedia Hebraica. Encyclopaedia Judaica.

Encyclopaedia Brukhaus–Efron.

Iberskaya Encyclopedia.

Encyclopaedia of the Diaspora: articles by A. Feldman, Klausner and others.

M. Davidzon – A collection on Bessarabia – Eretz Yisrael.

Bessarabia a collection edited by Haim Shurer.

David Vinitzky – Bessarabia he–yehudit be–ma'aroteha – The Jews in Bessarabia between the World Wars 1914–1940 [https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/Bessarabia01/Bessarabia01.html].

Articles by M. Kumarovsky on Akkerman.

Yisrael Schildkrauth – Akkerman the city I love.

Klutznick – Bilhorod–Dnistrovskyi published 1970–1973.

Pinkas haKehillot of Romania, A. Feldman.

Herget Encyclopaedia.

Conversations with Akkerman veterans – Y. Schildkrauth, Yehusua Harari and others.

Newspapers, “Unzer Tsayt” and others.

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bilhorod-Dnistrovs'kyy (Akkerman), Ukraine

Bilhorod-Dnistrovs'kyy (Akkerman), Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Oct 2020 by JH