|

|

|

[Page 18]

The History of the Jewish Community of Akkerman

When did the first Jews come to Akkerman? Who were the first and what motivated them to settle in this city? Unfortunately, to this day we do not have serious historical monographs on the first Jewish communities in Bessarabia and we also do not have reliable documentary material that we can base our attempts on answering the above questions. In any case, we have almost no documentary material on the beginnings of the Jewish settlement in Akkerman. The first testimonies on the presence of Jews in the city, and even these are very few, are from the 15th century AD and rely on foreign historical sources, or tourists who occasionally visited the place or any mentions in various books. Few documents have been preserved about the days of Turkish rule, although there is no doubt that by then there were already quite a few Jews in the city. Anyway, whoever wants to explore the reality of those days, and to unfold a picture of the life of the Jews then, their occupations and lifestyle, will lack the first infrastructure and will have to rely mainly on assumptions and guesses. Therefore, it is no wonder that we, too, groped in the dark as we tried to find an answer to the questions presented above.

The first mention of Jews in Akkerman, and it is also brought in the studies of A. Feldman, M. Davidzon and others, about the history of the Jews of Bessarabia, is related to the first century. One of the emissaries of Jesus Andrew, brother of Saint Peter, who was sent to bring the gospel of Christianity to the settlements on the shores of the Black Sea, tells that he arrived in the city of Tyras and found Greeks and Jews there. The very fact that this apostle mentions Jews proves to historians that he is not talking about a small number, but about many Jews. It is also possible, that the very presence of Jews in Tyras is the real reason for Andrew's journey to these places. Various Romanian historians also emphasize the fact of the presence of Jews in Tyras, Akkerman in the future, without bringing any further details.

Were there Jews in Akkerman during the days of the various tribal invasions of Bessarabia until the 11th century? We also don't have a reliable answer to this question. Presumably, the invasions of the barbarians and the many wars, that took place in the area, drove the residents away from the environs, among them also the Jews. We cling to the testimony of the Russian historian, Nestor (died about 1100), that the Khazars also ruled Tyras. On the other hand, there is no doubt that in the 13th and 14th centuries there were Jews in Akkerman, whether they came from Genoa together with the Italians who settled in Akkerman and have done a lot for the establishment of the trade and the economy in the city, or whether they arrived in other ways after the economic prosperity that began to show signs in the city and the surrounding area. There is also reason to believe that some of the Khazars' Jews, who are mentioned in Nestor's notes, remained in the place and maintained a traditional Jewish way of life.

The Metropolitan, Grigorij Camblack, author of the story of the life of the Christian martyr, Saint John's Day, who was murdered by the Tatars around the year 1300, mentioned in his story a Jewish settlement that was at that time in Akkerman, and even noted that the Jewish population in the city was concentrated in a special neighborhood. This Metropolitan of Moldova lived in the first half of the 16th century, and his story is probably based on folk tales and beliefs prevalent in Akkerman in the first half of the 15th century. According to the opinion of A. Feldman in the “Encyclopedia of the Diaspora,” the Romanian historian, Nicolae Iorga, relied on the above story when he wrote that Akkerman was “full of Jews” in the first half of the 14th century, and they came there following the conquest of the city by the Tatars.

More reliable information about the Jewish community of Akkerman dates back to the 15th century, during the reign of the Moldovans who showed a tolerant attitude towards the Jews. During the reign of the Moldovan prince, Stephen the Great (in the second half of the 15th century), many Jews came to the cities of the Black Sea coast, among them Akkerman and Kiliya. In an article on the Jews of Bessarabia by M. Davidzon published in the periodical “Gesharim,” it was said among others: “Mr. Khalifa wrote in his popular notebook about Bessarabia, which was published in 1914, that when he comes to the period of the principality of Stephen the Great, and when he speaks of the human material composition of the settlements in the coastal cities Akkerman and Kiliya, he counts, besides the Moldovans as locals, also the Greeks, Italians and Armenians, but his heart does not let him mention the existence of Jews there, even though everyone admits, and it has already been proven by historical document which cannot be denied, that when Stephen the Great sat on his throne of his principality there was already a strong and valuable Jewish community in Akkerman.”

[Page 19]

The researcher, M. Davidzon, did not interpret on what basis he came to the conclusion that “a strong and valuable Jewish settlement existed in Akkerman in the days of Stephen the Great,” and it is possible that this determination is far from historical accuracy. However, on the other hand, it is known that in the palace of Stephen the Great lived a Jewish adviser named Yitzhak ben Binyamin Shorr, who had a considerable influence on the state's affairs. It is also worth noting, that Yitzhak Beg, the Jewish physician of the King of Persia, also confirmed the presence of Jews in the area. This is another written proof that strengthens our determination that there was already a Jewish community in Akkerman in this period. We can assume that many Jews from Byzantium were pulled to this area, which had something to offer the Jews especially during the period of the expulsion of Spain, when they tried to find a hold outside the inquisition regime.

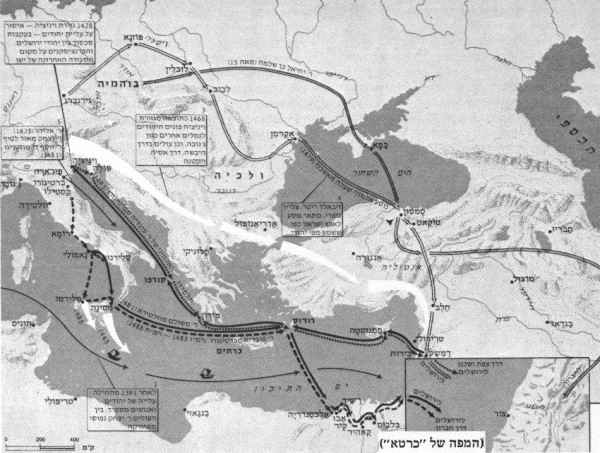

The first reliable information of a massive presence of Jews in Bessarabia tie to the eastern trade between Poland and the countries on the Black Sea coast, in which Jewish merchants from Poland took part in the late 14th and 15th centuries. Jewish merchants from Constantinople, which was already in Turkish hands, also passed through the cities of Bessarabia on their way to Poland, and presumably quite a few of them lingered in the place for a short or long time. According to documents discovered in the municipal archives of Lvov (Lemberg), it turns out that in the years 1467–1476 three Spanish Jews from Constantinople, who also had agents and aides, were active in the trade between Lvov and Constantinople. Although Akkerman's name was not mentioned in these documents, only Kiliya and Rani as places where Jews lived, it must be assumed that the Jews of Akkerman, a fortress and port city, also participated in this trade.

Since the 15th century, and mostly from the 16th century, there is already a lot of information about Jews in Bessarabia and Akkerman. The uniqueness of these reports is that they are of Jewish origin. In various sources we find information about merchants from Poland who passed in the cities of Bessarabia (Kiliya, Rani and Akkerman) for trade purposes. The rulers of Poland, Sigismund Augustus and Stephen Báthory granted concessions and special rights to merchants, or Jewish agents, who developed the trade between Poland and Turkey. Echoes of this movement of Jewish merchants from Polish cities to the cities of Bessarabia in the late 16th and early 17th centuries (1558–1616), were preserved in the books of questions and answers of the rabbis of that period: R' Yoel Sirkis (BAyit CHadash), R' Binyamin Aharon son of R' Avraham Selnik, R' Binyamin Meir son of R' Gedalia of Lublin (the Maharam of Lublin). From one of the answers of R' Yoel Sirkis, written in 1591, we learn that in that year there was already a Jewish community in Akkerman with a rabbi and judges.

And so it says in this certificate:

”Before us, we the young people of the Holy Community of White, came to us… we wrote and signed our names here the White City, Monday 17 Sivan 5351 [9 June 1591]… I, Avraham son of R' Shlomo may he live a good long life… wrote here the Holy Community White… Binyamin son of HaRav R' Eliezer… witness Yakov son of HaRav R' Yosef Dayan, Yudah son of HaRav R' Yom Tov Dayan, Shlomo son of HaRav R' Yakov Dayan.”

It should be noted, that during a certain period immigration from Poland and Germany to Eretz Yisrael was conducted through Akkerman. M. Davidzon writes in his article in “Gesharim”:

“It can be assumed, that all the popularity and publicity in those days for Bessarabia in general and Akkerman in particular, maybe also came thanks to the Holy Land that the entire Diaspora aim for, and in all its efforts it sought the nearest and most convenient way to reach it, and already then there were many who found this path, Akkerman – Eretz Yisrael, to be the shortest and most convenient.”

Another testimony, which confirms the convenience of this road for travelers to Eretz Yisrael, comes from the traveler, Riter Zebler, who in his records from 1479 advises Jews coming from the countries of Germany to Jerusalem to make their way on land: “First (they will travel) from Nuremberg to Poznan in Poland – 70 German miles. From Poznan to Lublin – also in Poland – 560 German miles, from Lublin to Lemberg – 530 German miles, from Lemberg through Wallachia (to Choczim – Khotyn) 530 German miles, from Khotyn to Weissenburg (Akkerman) on the sea, which is a city on the edge of Wallachia, 530 German miles. From Weissenburg, by sea, five or six days of travel to Samsun a city in Turkey, and from Samsun about six to seven days of travel to Shoket, etc.”

Therefore, Akkerman was an important transit station on the immigration route of Jews to Eretz Yisrael. It is possible, that there were Jews in the city who were able to help the immigrants to Eretz Yisrael to continue on their way from Akkerman and beyond. There's also an assumption that there were also those among the immigrants who stayed in Akkerman for a while and even settled there after realizing that they could survive and make a living in this city.

Karaites

A chapter in itself is the matter of the Karaites in Akkerman. As is well known, many Karaites concentrated in the Crimean peninsula and from there spread across the environment. By the middle of the 16th century we already find the following Karaite sages in Akkerman: R' Yehudah ben Eliyahu Tishby, who completed and copied there in the years 5271–5278 [1510–1517] the book “Yesod Mikra” which was written by his grandfather, Avraham ben Yehudah; R' Keleb ben Eliyahu Tarno, who copied in Akkerman in the year 5291 [1530], the book “Etz Chaim” and in the year 5303 [1542] the book “Gan HaEden” both by R' Aharon ben Eliyahu Nicomedia, and also the well known Karaite sage, Caleb

[Page 20]

Afendopolo ben Eliyahu and his brother Shmuel Ha–Ramati (Encyclopedia of the Diaspora). The last, called R' Caleb Aba, who was a student of R' Eliyahu of Bashyazi, “lived at the end of his life in the White City (Weissenburg – Akkerman) and died there in the year 5270 (1509). In his book of poetic phrases and poems, “Gan Hamelechn,” one can also find two lamentations about the expulsion with God from foreign lands and the lands of Russia and Lithuania” (”Gesharim” – M. Davidzon).

A. Feldman mentions in his study, that in the second half of the 16th century the following Karaite sages stayed in Akkerman: Shmuel ben Shlomo Ramati, also called Ramati of Akkerman, and Eliezer ben Yosef Tzdik. There is reason to believe that the Karaite community continued to exist in Akkerman throughout the 17th century. In the Karaite cemetery in Chufut Kale there is a marker (tombstone?) “In memory of the honorable rabbi, the beloved Yitzchak, who is called Tzsli ben Eliya the elder who died in Ac–kerman on 8 Av 5424.” Another helpful testimony is the Torah scroll that was found in the city with the inscription “Synagogue of the Karaite community of Akkerman,” and on is written that it is from the 1500 (the Torah scroll was transported to Constantinople).

Many legends have been told about the tower and its turrets. Each generation has added its own personal touch to these legends and it is difficult to distinguish between imagination and reality in these legends, which added to the aura of mystery and romance to the fortress which is a kind of a hallmark and a sign of uniqueness of the city of Akkerman for many generations.

|

|

[Page 21]

Y. Schildkrauth tells in his book:

“In the ancient and abandoned cemetery of Akkerman which, in the course of time, became a private vineyard and where later the new quarter, Novi Akkerman, was built, a long and narrow stone in the shape of a sloping roof was found during the excavations for the cornerstone of a new house. On both sides of the stone, to its lengthwise and widthwise, were deeply engraved letters arranged in even short rows. Apparently, the inscription on the stone was a song of praise for a deceased Jew from Akkerman, important and endearing. The eulogy is written in rhymes with words divided in places, in such a way that part of the word remains in one line and the other part is moved to the following line, a matter that made it easier for the writer to maintain the size of the row, or for the sake of getting the necessary rhyme, as was the custom of the rhyme writers and poets of that time.

Schildkrauth writes the following:

“This stone was laid for a long time in the synagogue's courtyard and many people came to investigate and decipher the damaged letters that had been erases over the years – for a long time, or many months, they were busy deciphering the contents of this tombstone. People from other cities of Bessarabia, who were also interested in this tombstone, came especially to Akkerman to assist the investigators of this tombstone (M. Davidzon and others). And these are the people from Akkerman who engaged in the deciphering of the content of the stone: the teacher M. Starec, the principal Yakov Berger, R' Haim Kaminker, R' Hirsh Brodetsky, R' Aharon Cohen, R' David Berkowitz, Yakov Rabinowitch, Leib Shohat, the writer of these lines and others.”

I must add, that in a conversation I had with Mr. Tzvi Manueli, he emphasized that the person who made a crucial contribution to the decipherment of the inscription on the tombstone was the historian A. A. Harkavy, who came especially from St. Petersburg or Odessa, to decipher the inscription. Dr. A. A. Harkavy has dealt with the history of the Karaites and his many researches on historical subjects are still used today as study material in various universities.

According to the first letters at the beginning of each line, it turns out that the name of the deceased was Yehudah ben Tanach (?). It is not known to which community the deceased belonged to and the author of the tombstone's text, but it is most likely that the tombstone is from the beginning of the 16th century – the year 5287 (1527). Therefore, it turns out that even then Akkerman had a Jewish community with righteous and humble people.

The tombstone's text was copied on parchment in two copies and handed over to the community committee and Beit HaMidrash. The stone was placed in a special place in the cemetery.

[Page 22]

In the days of Turkish rule

The trade movement from Poland and Russia to Turkey, which passed through Akkerman, probably brought many Jewish settlers to Akkerman during the Turkish period. There is no reliable information about the economic situation of the Jews and their legal status at that time, but, presumably, they enjoyed the freedom of religious worship and were able to engage in their occupations. Various reports confirm that the Jews who lived in the Budjak plains, which was mostly inhabited by the Tatars, did not suffer persecution and even received legal protection from the authorities when needed. From this, it can be concluded that the Jews of Akkerman were not discriminated against and were allowed to engage in any craft. The Jews who lived in the fortified cities – and Akkerman is one of them – traded in brandy, tobacco, hides, grain and wines. From Poland they brought corals, cotton threads, coffee, perfumes, upholstery materials and fabrics as well as spirits.

Even in the 18th century, Akkerman was a transit for goods transported to cities on the shores of the Black Sea, but to a lesser extent than before. As mentioned, it was caused by the development of new means of transportation in Brăila, Galați, Ismail and others which slowed the pace of movement through Akkerman.

The Jews also engaged in various crafts. As in any Jewish community, there were butchers who are a necessity for every community, Jewish tailors who are also a necessity due to the prohibition of shatnez [linsey–woolsey], bartenders, Jewish tenants etc.

We do not have reliable information on the patterns of organization of the Jewish community during this period, but presumably there were some since Jewish public life was already created at that time in many Jewish communities. We do not know about the synagogues that existed then and their uniqueness. If any documents and testimonies have been preserved about the lives and the development of various Jewish settlements in Bessarabia, urban and rural, as well as about various synagogues and charities, then this is not the case with Akkerman. We are groping in the dark until the period of the Russian occupation of the area. The frequent wars between the Russians and the Turks in the late 18th century over the control of Bessarabia, had implications for the development of the Jewish community of Akkerman, which was one of the battlefields and depleted the local Jewish population. We have sources of information about the situation and lives of the Jews of Akkerman only after the defeat of the Turks and after Akkerman passed to Russian rule in 1812, as will be explained below.

|

|

[Page 23]

The Jews of Akkerman Under Tsarist Rule in the 19th century

After the Bucharest Agreement of 1812, the territories of Bessarabia passed from the Turks to the Russians. The frequent wars that have taken place in these territories depleted this region and its inhabitants. With the entry of the Russians masses of residents fled the cities and villages because they feared the Russians and the tsarist regime which was known for its harassment and the enslavement of the peasants to the nobles. The villagers especially feared the forced conscription of the population into the army, various taxes and economic decrees, and the harassment of the Russian administration. The first steps of the new regime were – the deportation of the Tatar residents, who were suspected as fans of the Turks, into Russia. The Budjak plains (Akkerman and Bender districts) were deserted, the population dwindled and the economic depression was well felt.

The Jews also fled from the region to places that seemed safer and more promising to them, and the population in the region was so sparse that the Russian authorities began to see it as a suitable place to for the exile of unwanted elements (the great Polish poet, Adam Mickiewicz, was also among the exiled to the Akkerman area and from there maybe the reference to the Akkerman's plains in one of his poems, as well as the Russian poet Pushkin).

With the passage of time, the authorities apparently came to the conclusion that this sparse region invites new occupiers and therefore decided to adopt a different policy. In instructions given by Tsar Alexander I in 1816 to the Commissioner of Bessarabia, Bohemteib, it has been said that he must take care of attracting new residents to Bessarabia, especially to the desolate Budjak region. As a result of this policy, masses of new settlers arrived in Bessarabia including French, Swiss, Germans, Bulgarians, Serbs and others, and people from other Russian provinces were also transferred there. The renewed momentum for the development of the region also brought masses of residents on their own initiative. With them were also many Jews who hoped to rebuild their lives in this part of the country, which seemed to them to have great potential for economic development. The authorities granted many concessions to the new settlers, distributed land to them, loans on favorable terms for the cultivation of the land and even release from the obligation of military service. At the same time, the Russian markets opened for products and produce from Bessarabia, and in the early 40s Bessarabia was already used as a large silo of the port of Odessa.

The Movement of the Jewish Population

It is not known exactly how many Jews were in Akkerman at the beginning of the 19th century. According to material found in one of the files stored in the archives of the governors of Wallachia and Moldova, there were only 90 Jews in Akkerman in 1808. Also, on the basis of the census conducted in 1817, it is not possible to arrive at a more accurate estimate of the number of Jews on that year, since Akkerman is included in this census within the boundaries of the Bender district without a separation for statistics between Bender and Akkerman. On the other hand, we know that Jews fled Poland to Bessarabia and the southern provinces because of the harassment.

The drought that befell Poland, and the economic depression, were also among the factors of immigration to southern Bessarabia. An expression of this is given in one of the stories of Mendele Mocher Sforim [Yankev Abramovich] – “The discovery of Wolyn,” and so it is said in this story: “Out of trouble, my grandfather went to Wolyn during the days of the great famine, went down to Kishinev [Chișinău], the capital of Bessarabia – a land flowing with milk and honey, engaged in teaching together with other paupers like him and enjoyed all the good, ate mamaliga, for dessert ate fat–tail sheep, drank wine and lived there peacefully like all Jews, and knew no trouble.”

Dr. A. Feldman explains in the volume on Bessarabia published by the “Encyclopedia of the Diaspora,” that the new Jewish immigrants belonged to the economically and socially weaker classes of the population. They engaged in small trade or crafts and quite a few engaged in brokerage. Culturally they did not stand at the top of the ladder. Most of the immigrants to Bessarabia settled in the north of this region, or in the center, but most of them were absorbed in the south. The numbers speak for themselves. If in 1808 there were only 90 Jews in Akkerman, then in 1861 there were according to the count 1,797, and by 1864 the number of Jews had already reached 2,422. This increase in the Jewish population is especially noticeable if we compare it with other cities in Bessarabia.

[Page 24]

| According to 1816–17 census | According to 1864 census | ||||

| The district | The cities growth rate |

The Jewish population |

% in relation to all residents |

The Jewish population |

% in relation to all residents |

| Kishinev | 2000 | 40.0 | 20385 | 24.7 | 919 |

| Khotyn | 1000 | 66.6 | 6342 | 48.3 | 534 |

| Soroca | 1020 | 38.7 | 4135 | 76.4 | 417 |

| Balti | 1975 | 39.7 | 3124 | 38.7 | 156 |

| Orhiyov | ? | ? | 3102 | 72.1 | ? |

| Bandar | 110 | 6.4 | 4297 | 28.2 | 3771 |

| Akkerman (1808) | 90 | 5.4 | 2422 | 12.1 | 2591 |

As the economic and political pressure in the cities of the “Pale of Settlement” in Russia intensified – so grew the rate of immigration from there to Akkerman, so much so that in the 1897 census there were already 5,613 Jews who constituted 19.9% of the total residents in the city. On the other hand, there was already a certain slowdown in the growth of the Jewish population in the following years, and in the 1910 census 5,802 Jews were registered. It is reasonable to assume, that the development of new means of transportation caused a certain devaluation of the status of city of Akkerman as a transit city for trade, and from here also the small increase in the percentage of the Jewish population in the city.

In 1918, with the entrance of the Romanians to Bessarabia after the First World War, Akkerman was cut off from its living space, until now Russia, and the Jewish population decreased. In 1925, the Jewish population reached 5,000 people, while in the census conducted in 1930 there were only 4,239 Jews who made up 12.3% of the total population. In 1940, with the Russian occupation, the Jewish population grew and reached 8,000, which made up 16% of the total population, but there are completely different reasons for this increase and they will be discussed in the chapter on the Holocaust.

Employment and Economy

The sources of livelihood of the Jews of Akkerman were not different from those of the Jews of other cities in Bessarabia. It can be said, that they enjoyed certain reliefs and discounts that did not apply to other cities because of Akkerman's considerable distance from the international border of Russia.

In the of the authorities' directives published in 1818, it was determined among others that the Jews of Bessarabia constitute one of the nine ethnic groups of the population of Bessarabia, and they have to pay taxes and municipal tax like all citizens depending to their occupation: merchants in the city or farmers. They were allowed to trade freely in all areas of the region and also develop trade relations with other regions in Russia. Indeed, the directives also contained restrictions on Jews in regards to purchasing private land, but when it came to livelihoods, small trade and other trades, there was no restriction. Therefore, there is reason to assume that the Jews of Akkerman also enjoyed all the rights and discounts granted to the Jews of Bessarabia. They integrated into all branches of trade and crafts and even purchased plots of land for construction.

The agriculture in this area was in a state of rapid development, the vineyards areas have been expanded and wine production increased, thousands of dessiatin of grain and seeds were sown and many Jews entered the trade business, brokerage in agricultural produce, and even engaged in large–scale import and export. In the 60s of the previous century, the wine production in Bessarabia reached about three million buckets a year, while Akkerman's share was about a third. According to testimony of an authority figure (Zashtzuk), which is also brought in the research of Dr. A. Feldman, almost all the taverns in Bessarabia were owned by Jews and the sale of liquor was a Jewish monopoly. Zashtzuk mentions the “Jewish lessee, Karasik, who in 1873 leased the sale of beverages on state and private estates in the Akkerman district.”

It is worth noting the large share of Akkerman Jews in the craft industries. They managed to get along with the Christian craftsmen and had almost complete control over certain trades: tailoring, furriers, shoemakers, tanners, etc.

In 1865, Count Stroganov informed the Minister of the Interior, on the basis of a report submitted to him by the governor of the region of Bessarabian region that all branches of labor, including those who require hard physical labor, are in the hands of the Jews.

The Jews of Akkerman purchased land not only in the city but also in the area to cultivate it. Under Russian law, the Jews were not allowed to purchase land and settle within a 50 verst [53.34 km] radius along the border, but they were able to purchase land near the Dniester. It is known that the owners of the Christian estates filed a petition with the emperor against the Jews who purchase land in places forbidden to them. The petition was sent by the Ministry of the Interior to Count Stroganov for investigation and opinion. Stroganov, who supported the demand of the landowners, asked for the opinion of the district management and the military governor, General Ilyinsky. The later suggested to forbid the purchase of lands by the Jews only in the districts of Khotyn, Soroca, Orhiyov, Yasi (Balti) and Kishinev, but to allow the Jews to purchase lands in the districts of Bandar and Akkerman.

[Page 25]

The local authorities in the towns occasionally implemented the law prohibiting the settlement of Jews in villages close to the border in the spirit of the above–mentioned regulation and expelled the Jews who settled there. It is known, that in 1890 fifteen Jewish families were expelled from Tatarbunar in the Akkerman district, and the reason was: they settled in the town after the set date, 27 October 1858 (the town was established in 1809). Even though Tatarbunar had the status of a town for the purpose of enforcing the anti–Jewish law, it was given the status of a village and the Jews, who were expelled from this village, move to cities where they were able to integrate into the economic life. In the second half of the 19th century the law was frequently enforced, but since Akkerman was a city the Jews within it did not suffer from this discrimination.

When industrial plants began to develop in southwestern Russia in the second half of the 19th century, and the first buds of a capitalist economy emerged, this process skipped Akkerman. Industrial plants were not opened in the city but, on the other hand, there was considerable momentum in the development of agriculture. The Jews bought the farmers fruit while on the trees and gave them payment on account. Even before the farmers began to sow there were Jews, who bought the grain in advance and by doing so the farmers' fields were enslaved to the urban Jews.

We find evaluations on the economic situation of Akkerman's Jews in various sources. The Maggid of Slutsk, Tzvi Hirsh Dainow, who visited Akkerman in 1869, wrote: “The Jews of this city most of them poor, destitute, needy and paupers – – – the status of the Bessarabian Jews is terrible and most of them are idler like their brothers, the Jews of Lita and Zamut.” On the other hand, we find a completely different assessment with the author, Zalman Epstein, who described their situation in an article published in [the Hebrew newspaper] “Ha–Tzefirah” on the eve of the 1881 pogroms: “Their good physical condition (is similar) to that of the rest of the Russia's Jews – – – the trade, which is almost entirely in the hands of the Jews, will flourish here in a superior manner – – – thousands of steam carriages carry, year after year, the grain of the land to Odessa and from there abroad through the sea. Apart from this main trade, the trade in sheep wool, oxen and wine will also be very successful – – – the craftsmen will find their livelihood at ease and not in sorrow – – – there are many rich people here among the Jews.” When he compares the situation of the Jews of Bessarabia to that of the Jews of Lita, the author says: “This country is truly like the Garden of Eden – – – also the poor people eat meat every day and drink wine, and for that their faces will produce life and emotional–strength.”

Only 12 years differentiate between the first and second testimony – and the assessments are completely different. It is possible, that the second author used high and poetic language recommended by “Bat Hashamayim” [Haskalah movement] and it is possible that he saw it from his innermost thoughts. It is also possible that they both visited different places and hence the difference in vision.

Contrary to what has been said, we know from more qualified and less “poetic” sources that there was a considerable deterioration in the economic situation of the Bessarabian Jews, which began to show signs from 1880 onwards, and its traces were also clearly seen in the Jews of Akkerman. Due to the frequent deportations of Jews from the villages the cities were filled with many unemployed Jews. The 1880s and 1890s were known to be years of severe agrarian crisis in Russia. Grain prices in world markets deteriorated drastically and reduced the farmers' income. The crisis was felt in full force in Bessarabia whose economy was based mainly on agriculture. The emigration of Jews from the villages was well felt in Akkerman because there were no sources of livelihood for the new residents in the city. The stagnation in trade was well felt and many sources of livelihood were blocked as described in one source: “The shoppers stopped (buying), the merchants and the agents mourned and lowered their heads. Many are the artisans and laborers (craftsmen) who go idle.”

At that time, many Jews in the city needed “Kimcha DePascha” in preparations for the holiday of Passover, and the growing impoverishment had implications in all areas of Jewish life in the city. The Jewish Colonization Association began to distribute support funds to the needy whose number increased. Many came to the conclusion that there's no choice but to take the wandering stick again and sail far and wide to seek subsistence and livelihood.

The Spiritual–Cultural Image of Akkerman Jewry

How did Akkerman Jews shape their spiritual–cultural lives during the tsarist regime? Is it possible to compare Akkerman's Jewry with that of Poland, Lita and Galicia in this respect? What were the reasons why the Bessarabian Jewry, Akkerman included, were not among the cultural and spiritual centers such as those in Europe at the time, and why they did not establish serious institutions for Torah study and raise generations of scholars, teachers, etc.?

It is not an easy task to answer these questions in a complete and comprehensive answer. We will turn to the sources and try to see what was written on this subject in those days. In 1832, an educated man named Tzvi ben Avraham Balaban of Brady, who was also called by the name Rabinowitch (and lived at that time in Kishinev), describes the situation in a letter to his friend: “Of all our brethren our allies, who live in European countries, the Jews living in the country of Russia stand on the lower step of the steps ascending in the ladder of wisdom … but our brothers, residents of the district of Bessarabia, have not yet reached this step. Ignorant, stupid, and

[Page 26]

lacking resourcefulness, and anything that has an opinion, understanding and intelligence will be expelled from their homes… and the doctrine of man, even though it is always walking hand in hand with the innocent Torah, has been thrown behind their backs – – – the Torah, and good deeds, are considered nothing in their eyes, all the more so, wisdom and foreign languages. The interest and occupation of its residents, all day long, is to raise capital and save, to eat in revelry and drink the wine often kept in their caves at mitzvah meals” (published in “ha–Boker Or” [The Morning Light] 5660, 194–196).

If we remove the coverage of the rhetoric that characterized the style of that period, there is a very deadly verdict in these words on the Jews of Bessarabia, Akkerman included, and it is possible that several words were written for the glory of poetic phrases. But, for sure, there is a nucleus of truth in these words considering the Jewish human material that came to this region and scattered across the cities and towns of Bessarabia. They did not bring with them a rooted culture, generations of Jewish tradition, deep awareness for Jewish education and the like. They came from the weakest strata of the Jewish population, socially and economically, and they could not be expected to reach greatness and significant deeds.

The conditions in the towns of Bessarabia were not fit for cultural growth. We cannot forget that this region, villages and cities alike, was usually sparsely populated and, even more so, the Jewish population. What centers with a massive Jewish settlement can contribute and operate in the spiritual and cultural area cannot be done in settlements with low population. Patterns of Jewish tradition were not anchored within them due to the absence of a broad stratum of educated Jews who engaged in Judaism and the Torah. When the region of Bessarabia was occupied by the Russians, it lagged culturally and there were no serious educational institutions in it. This was especially noticeable in the small settlements. Wealthy Jews sent their children to study in the big cities such as Moscow, St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kiev, etc., but most of the Jews had to make do with what was, and what was culturally – was meager and poor.

The Jews enjoyed the political and economic constitution granted by the government to residents and new immigrants, and this helped to develop the patterns of life that were far removed from the traditional Jewish way of life, as it was, for example, in Poland.

The main aspiration of the Jews – to penetrate new branches of livelihood and trade and also to engage in agriculture (in the villages), motivated them to follow in the ways of the non–Jewish population, to imitate their customs and way of life. Many insisted that the Jews of Bessarabia did not observe the mitzvoth and the Shabbat. The northern region of Bessarabia had a more Jewish and traditional character than the central and southern part, but it also did not satisfy “Shlomi–Emuni Yisrael” [Union of the Faithful in Yisrael]. For example, R' David Eybeschutz, who was the rabbi of Soroca in northern Bessarabia in the first decade of the 19th century, complained about his congregation: “There are many defective things in them, among them those who speak aloud in the synagogue – and when the Sabbath comes they resent it by saying – that if they did not have the Sabbath they would earn money working in the Wine–House: – – – “Instead of engaging in the Torah on the Shabbat, they eat and drink and sleep and later go for a walk – – – and after half a day they light up a fire in the Wine House.”

The very fact that Rabbi Eybeschutz repeatedly emphasizes the matter of the “Wine House,” shows us the attractive power of the wine houses, which were probably numerous in this part of the country whose wine industry was its number one industry.

The influence of the Christian environment was great on the Jews. Unlike in Poland, there were many Jews in the cities of Bessarabia who walked bareheaded, sent their children to study in government schools and universities and not to “hadarim” and “yeshivot,” did not adhere to kosher laws, etc. The intellectual circles, which arose in many cities, further alienated the Jewish youth from the religious–traditional life.

This general atmosphere also characterized the Jewish community in Akkerman. Akkerman's proximity to a cultural–economic center such as Odessa, as well as the close ties with the center of the Bessarabia–Kishinev region left their mark on the character of the Jewish community in our city.

It turns out that the process of Russification in Akkerman took on different dimensions than in other cities. It can be said, that this was an accelerated process, so much so, that many of those who dealt with the history of this region define Akkerman as the “other city,” more “gentile,” than other cities in Bessarabia, and there were also those who called it a “reckless” city from a Jewish point of view. The renowned preacher, Tzvi Hirsch Masliansky, one of the leaders of “Hovevei Zion” who gained a reputation for his sermons in Russian cities, also came to Akkerman in one of his journeys for a speech, or for a “sermon,” and in his memoir he writes about his impressions from this visit:

“How different are Akkerman Jews from ordinary Bessarabian Jews! It is hard to believe they are from one district – – – their way of life, their customs, their clothes – are a copy from their neighbor, Odessa. Odessa spreads its wings over her little sister, Akkerman, imprinted on it the European seal and removed the cloud of the Bessarabian spirit – – – when you delve into the understanding, that Akkerman learned from Odessa only the “lawlessness,” the rebelliousness of religion, the Jewish customs with their attributes, the sanctity of Shabbat and Jewish religious festival – – – the uneducated rule in Akkerman as in all the cities of Bessarabia.”

[Page 27]

|

|

|

|

[Page 28]

Even here we have before us a decisive verdict on the way of life of the Jews of Akkerman. If a personality like Tzvi Hirsch Masliansky, that we cannot associate him to a sect of extremist zealots, issues such a verdict and states that Akkerman learned only lawlessness from Odessa – are truthful words, and there is a place to assume that Akkerman was indeed different, and the change was not very visible to those who were accustomed to a different form of Jewish life in Jewish communities in Russia

The accelerated process of Russification in the southern regions of Bessarabia, “stabbed the eyes” of outsiders, who apparently could not come to terms with the complete control of the Russian language in Jewish homes, with a very small number of Yiddish readers compared to many Russian readers. From one statistic we learn, that the percentage of Russian readers in the district has reached 28 while in Akkerman to 43!!! – the highest in all the cities of the region.

It cannot be concluded on the basis of the above, that the Jews of Akkerman were detached from Jewish tradition and from the affinity to the sanctity of Judaism. On the contrary, there were also Hassidim in Akkerman who remained loyal to their rabbis and to various dynasties to which they belonged before they moved to Akkerman, but, in comparison, the number of “opponents” in Akkerman was greater. In any case, there is no doubt that there was never a center of Hasidim in Akkerman, the city marched in its furrow, apparently formulated a Jewish way of life that was in line with the needs, and the level, of the culture of the city's Jewish residents.

There is no doubt that also in the first half of the 19th century various rabbis sat on the rabbinical chair in Akkerman, but their impact is not noticeable and we are unable to tell about them. On the other hand, it is known that the rabbi of the city of Bandar, R' Arye Leib Wertheim, also had an impact on the Jewish community of Akkerman which was apparently under his spiritual patronage.

The first buds for the formation of a Jewish community appeared in Akkerman as early as the beginning of the 19th century. Three years after the city passed into Russian hands, in 1815, Beit HaMidrash had already been built and the very fact that the Jews saw the need, and were able to establish a spiritual center for themselves, indicates that they were already a serious part of the population at that time. From a notebook from 1807 found in the Beit HaMidrash, we learn that in 1865 there was a pogrom against the Jews of Akkerman (what was the nature of the pogrom? we do not know on the basis of these lists, but it must be assumed that there were no victims and the rioters were only satisfied with the looting of Jewish property).

“Chevra Kadisha” was also established in 1807. In 1828, the Old Synagogue was built (the future Great Synagogue) and 19 years later, in 1847, “Chevra Kadisha” also established the Old Kloyz.

The Craftsmen Synagogue was built in 1903, and until than the craftsmen prayed in a private room, dim and half–ruined, at the home of R' Chaim Prectman on Izmailovsky Street. According to what is told in Schildkrauth's book, on holidays and festivals the Jews also gathered for prayer in private homes, or in the apartments of various institutions, which became improvised places of worship during the holiday.

It is worth noting, that even if the Jewish community of Akkerman did not produce well–known scholars there were, within it, many scholars and God–fearing Jews who studied the Torah in private and in public, and kept a light mitzvah as a severe one. There were Shas and Mishnayot societies in Beit HaMidrash, and they marked the end of the study of a book in splendor and in a large audience alongside tables set for a meal, as the speakers season their words with Torah innovations and competed with expressions of proficiency and wit.

In his book, Schildkrauth lists the names of Jews in Akkerman who were great Torah scholars, such as: R' Moshe'le Zuckerman, R' Ben–Zion Chava–Libes (Schildkrauth), R' David Brend, R' Chaim Chava–Libes (Kaminker), R' Yosele' Levin, R' Hanoch Shapira, R' Aarale, R' Moshe Leker, R' Leibele the slaughterer (Hirschfeld) author of “Penei Arye,” “Amrei Baruch,” and others. It seems to me, that anyone who counts eight names in the city takes a little risk, for you never know if you are not missing someone worthy of being counted among the great scholars.

The Jewish education in the 19th century was concentrated only in “hadarim” and “Yeshivot” did not exist in Akkerman. Even though attempts have been made to establish Yeshivot they did not last long, either due to a lack of teachers or the lack of means to upkeep them. The first attempt was – to set up a “yeshiva” in Shagansky's home on Jewish Street not far from the Leman. This one lasted about two years. The second attempt to establish a yeshiva was held at the home of Shlomo Hacham on Mikhailovsky Street. It was kind of “modern” Yeshiva since hours were also devoted to secular studies such as: the history of Israel, grammar and arithmetic. However, also the “modernization” did not help and this Yeshiva did not last a year. In conclusion, if someone desired, or his parents desired, more serious Torah studies – he had no other choice but to turn to Yeshivot in Odessa or Kishinev.

[Page 29]

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

[Page 30]

Schildkrauth writes about the study in the “hadarim”: “There were different “hadarim” and Gemara teachers in the city. The well–known Gemara teachers in the city were: Rabbi Hirsh–Wolf, Rabbi Yossi, Moshe Yankel the long, Rabbi Moshe–Wolf, Rabbi Yizi, Yona the melamed, and others. There were also homeowners who imported “foreigners,” meaning, outside of Akkerman, those lasted one or two “periods” and disappeared. An exception was Rabbi Nachum, whose students called him the “Angel of Death” because he severally beaten the student who did not memorize the lesson properly.”

From various articles, published in the 1880s and 1890s in the general press, as well as in the Hebrew press, we learn that at that time there was a shortage of high school education in all Russian cities. Of course, the “Haskalah” [Jewish Enlightenment] “Bat Hashamayim” [Daughter of Heaven], also reached Akkerman, circles of maskilim had a subscription for Hebrew newspapers that came from St. Petersburg and Moscow, and the problems of the Russian Jewry were also at the center of the world of Akkerman's Jews. Indeed, the 1880s pogroms in Russia did not befall the Jews of Akkerman, but their influence was considerable and we will discuss this elsewhere in this essay.

Testimonies from “Ha–Melitz”

In issue No. 44 of the [Hebrew Newspaper] “Ha–Melitz” from 1889, an article was published on Akkerman. It was signed by “Mishal HaDalponi,” which is probably the pseudonyms of one of the maskilim from Akkerman, and so it was said among others:

“…this city, where more than six thousand Jews will live in, will not excel in anything from other cities, and may even fall short of them regarding its spiritual life. We do not have here, as in other cities, different societies to glorify the Torah, to spread education among the Jews, to support the fallen and be gracious to the poor.” The reporter did not write clearly, and did not explain to which societies he meant, and what's up with “to support the fallen and be gracious to the poor” in the spiritual life, as he defines. We only learn from this poetic article that its writer is distressed over the lack of association for the dissemination of education. In contrast, we read in Brockhaus–Efron dictionary from 1890, which is, undoubtedly, a more authoritative source than the reporter of “Ha–Melitz” in Akkerman that in 1885 there were 10 elementary schools in Akkerman and 596 boys and 18 girls studied in them. Among the educational institutions in the city there were also two pre–secondary schools with 4 classes, although this article did not mention the number of Jewish schools, or schools under Jewish management, but in “Iberskaya Encyclopedia” we found that Talmud Torah was founded Akkerman in 1882, there were also two schools for boys and two schools for girls, and a Shabbat evening school.

Presumably, the Jews encountered many difficulties in enrolling their children in government or municipal schools, but relative to their percentage in the general population, the number of Jewish students in these schools was higher than that of the other ethnic groups in Akkerman. The restrictions were particularly striking with regard to Jewish girls who, at one time, numbered fifty percent of all the girls in school, although it is not certain that there was a time when the Jewish population in Akkerman reached fifty percent of all residents…

In 1909, the municipality passed a resolution, under the pressure of anti–Semitic circles, to limit the number of Jewish students to only ten percent. The Jews had no other choice but to establish their own private schools so as not to deprive their children of education.

It is worth noting, that the Russian authorities did not approve the establishment of private educational institutions, fearing that they might be a source of social unrest that would foster opposition to the regime.

At the beginning, the private Jewish schools were far from Jewish education but, over time, there was a significant change in the trend of study, and this will be discussed later. In 1883, 41 students attended the private Jewish school owned by Gelfand. The second school was intended for girls and was under the direction of the teacher Bertha Davidovna–Kaufman.

The social–educational activity in the city, in the late 19th century, revolved around two big Jewish societies centered in St. Petersburg. The first was O.P.E – Obshextvo dlia Rasprostranenia Prosveshenia mezhdu Jervejam v Rossil (a company for the dissemination of education among Russian Jews), whose main activity, as its name implies, was in the field of education and assistance in the existence of Jewish schools or in Jewish administration. The name of the second society was, the society for the aid of poor Jews – Obshextvo Posobija bednyn Jervejam, and its duty was – financial support for poor Jews. Akkerman operated branches of these two companies and the Jewish intelligentsia in the city coordinated the social activities in both branches.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bilhorod-Dnistrovs'kyy (Akkerman), Ukraine

Bilhorod-Dnistrovs'kyy (Akkerman), Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 21 Oct 2020 by JH