|

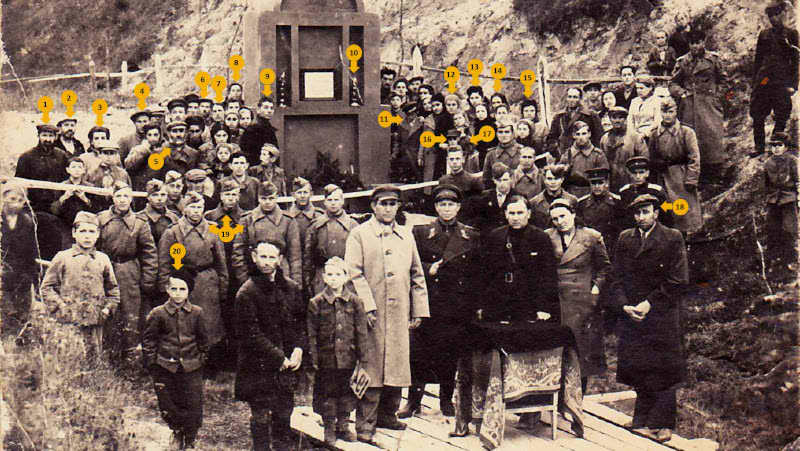

in the presence of Shoah survivors [who are called out, if identified, in notes below]

Original photo courtesy of survivor Gerry Steinberg

|

|

|

[Page 281]

[Page 283]

Yosef Litvak,[1] Jerusalem

Translated and edited by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD with Hanina Epstein

©

The New Administration

On the first of February 1940, the military government in our area was replaced by a civil government. This was after a “referendum,”[2] which was held in the areas which had been annexed to the Soviet Union following the division of Poland between the Soviet Union and Germany. During that same referendum upwards of 99% of all the people eligible voted as usual in favor of the annexation.

All the important positions in the new civil administration, even in a small place like our small town, were offered to clerks who were imported especially from Ukraine, from the other side of the old boundary (the boundary between Poland and Russia before September 1st, 1939).[3] Only the less desirable, essentially technical roles, were given to local clerks. In the [Communist] Party's local civil office, local men were not able to gain any kind of toehold.

Although theoretically one should not judge the policies of the regime based on what was done in a small town like Mlynov, it seems to me that anyone who happened to know the Soviet regime intimately will agree, because it is hard to believe that, in the installation of administration in the areas annexed to Russia, there was a room for accidental and atypical results, or that the matter was not carried out in alignment with the explicit policy and the clear and detailed guidance from the Center. Thus, in my opinion, one can also infer from the manifestation of policies and instructions which I witnessed in Mlynov, that they [those in the regime] were behind them.

The military government established only one other local entity: the village council (Mlynov had the status of a village). This council was in large measure a fictitious body for propaganda purposes only, and, also, in this area the council served as an implementation arm for the local military commander. The council ensured the full participation of all the town's inhabitants in the “referendum” on annexation. This village council was composed of a handful of local Jewish Communist members who were joined by one Ukrainian, a worker in the local flour mill, an ignoramus and boor, who never belonged to any political party and had no interest in politics.

When the military regime was changed to a civil government, apparently new orders were handed down from on high regarding the composition of the local government and selection of local men for the service of the State. A new village council was chosen and at its head stood the Ukrainian member mentioned earlier.

[Page 284]

The Jewish communists were all removed [from the council] on the pretext that they had been Zionists in the past. Moreover, they were disqualified from serving not only as representatives of the population but also in any government position whatsoever. (In other words, the new government completely overlooked the fact that already, during the last years before the Soviet conquest, these young people had ceased to be Zionists and had instead become Communist members, even suffering jail time for supporting Communism). It is possible, too, that another consideration being weighed was [the fact] that before the Soviet conquest there was not a Communist party in Poland recognized by Moscow, because it had dissolved earlier under the allegation that its ranks had been infiltrated by many provocateurs and, in fact, all earlier communists were suspected provocateurs, all the more so the young people mentioned earlier who had in truth once been Zionists and had family pedigrees that were not proletariat.[4]

To the new village council were appointed (i.e., “chosen unanimously”[5] at the suggestion of the government representative), 12 men, among whom was only one representative of the Jewish population, even though Jews comprised 50% of the population. The single Jewish representative was a Jewish woman – Dina Holtzeker[6] – who was chosen for the role, apparently because she had not been political in the past and because she had been formerly imprisoned, though her “stay” had been for criminal activity and not for Communism: She had grabbed a bank note [or bills] from the hands of a man – a Christian Czech – who had lent her money and she threw it into a stove right in front of him in his own home. She also lacked a proletarian pedigree and was a grocer. Before that she had embezzled from a Jewish woman grocer, but that [woman] preferred to litigate before the Rav [following Jewish law] and not in front of gentile law courts. In any event, this woman had a bad reputation among all circles of the population, although it was difficult, of course, to establish if they chose her [for the council] because of her troubled mind, or as contempt and ridicule directed towards Jewish women in the population.[7]

The Economic Situation

The economic situation of the Jewish population was quite bad. As mentioned previously, the Jews of the small town were small shop owners, craftsmen, waggoners and butchers. Apart from one pharmacist, no one had independent businesses [since everything was nationalized], unless you include two kosher butchers[8] and four teachers and educators (“melamdim”).

With the Soviet occupation, the source of Jewish livelihood dried up. All of the shops closed after their hurried, compulsory sale in only a matter of a few days. Only one “general store” continued to operate, which was established in the last years of the Polish government by Christian Poles as competition with Jewish commerce, with a sign “Christian Store” and the slogan: “What is ours is His.”[9]

The sign changed, the store was reposted as state-owned and served from then on as the only place providing the population with all kinds of necessary commodities.

[Page 285]

Theoretically [it supplied goods] – because in fact, this store had only bread and meager portions of basic commodities. Most of the goods, if they arrived, were sold by vouchers, which were given to Soviet officials exclusively.

The Jewish tailors tried to organize a cooperative that operated in line with a government order. Since there was an obligation to work on the Sabbath, and even on Yom Kippur, many older tailors quit and remained unemployed. The other tradespeople also had no work, since there was no demand and no concern [to retrain them]. The waggoners worked part time for different government authorities, but the amount of hauling was significantly reduced, and their wage was miniscule. About 20 young Jewish men and women obtained low-level clerical positions in the new offices. About 80% of the Jewish population remained without means of subsistence. It is unknown if the government had plans in the future for any kind of rehabilitation program for the benefit of the Jewish population, which had been deprived of their former livelihoods. In any case, during the 21 months of Soviet government until the Nazi occupation on the 22nd of June 1941, [the Soviet government] no efforts were made towards [their] “productivization.” There was also no unskilled labor. Indeed, there was occasional seasonal work in agriculture in the nationalized farms like gathering beets, sugar, potatoes, but in these kinds of work the entire population was “drafted” with no exception, apart from the elderly, children, and infirmed, and there was no compensation for this compulsory labor since this work was theoretically “voluntary” to “save the crop.”

In this situation, the Jews were sustained in part by the inventory of foods they were able to accumulate before the War, and from the barter of personal possessions with farmers in exchange for food. Some tried to engage in the black market, in other words, as a go-between in the business transactions mentioned earlier and in others, despite the great danger getting involved, but there was no other choice.

Therefore, to the extent possible to judge from the experience and example of one little town, although, as noted above, there is no reason to assume this small town was an exception – the Soviet government ignored the special situation of the Jewish population, that sprung from the unique economic and social structure that had crystalized over the course of generations. No efforts were made to constructively integrate them in society and in the Soviet economy. Moreover, the Jews were forced indirectly to continue non-productive occupations to subsist with one difference – that earlier, in capitalist Poland, the situation was at least tolerated by the regime, while in the new regime, this [non-productive] work was unlawful and brought on severe punishment in its wake. Furthermore – the former shopkeepers and their children, including those who had not reached maturity, were labelled as an asocial element and given special identity cards with the number 11 and other special symbols.

[Page 286]

With this kind of identity card, they were not able to go to live in the municipal seat, where it might be possible to learn a new profession, or acquire knowledge, so they could be transformed into a productive element.

The Jews were punished, therefore, for their lack of earlier productivity in the capitalist regime, as if this was their fault (according to the same logic they also had to punish the workers who were utilized in the capitalist regime) and the punishment was manifested as follows – the path to be transformed into productive member in the new regime was blocked – a situation that brought on still other punishments.

Community and Culture

Also completely quiet and paralyzed was the communal and cultural life. The youth movement, charitable groups, and the official Community (kehilla) organization stopped functioning. The “cheders” closed and stopped teaching Torah and Hebrew. Only the synagogues were not harmed, in the meantime, but they emptied out anyway, because, apart from the elders who had nothing to lose, a person who held out hope of work did not want to taint himself with “clericalism” [i.e., as being religious] or as a “counter revolutionary” for which going to the synagogue was understood to be a clear sign.

The “cultural” library was closed. All the books in it were destroyed, the majority of which were incidentally good literature and among them, the Yiddish sector, including even leftist and communist writers. In its place, a general cultural hall was opened, and assemblies for propaganda began, propagandistic films were screened, and dances took place every evening until midnight.

Apart from that, there were lessons for teaching the Stalinist Constitution,[10] but no profession-oriented courses, either for the youth or adults, nor courses to learn the official Russian and Ukrainian languages, knowledge of which was required to obtain clerical work of any kind. It is possible that here too, hidden considerations operated – since in any case the Ukrainians knew their own language and the Jews had no need to master it (the Jews, in fact, spoke broken Ukrainian but didn't know the rules of grammar nor how to write this language).

Translator's and editor's footnotes:

During the Shoah

Joint Testimony of: Yehudit (Mandelkern) Rudolf,[1]

Fania (Mandelkern) Bernstein, David Bernstein[2]

Translated and edited by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD, with Hanina Epstein

©

As told by Yehudit [Mandelkern] Rudolf

Already on Sunday, June 22, 1941, with the outbreak of war between Russia and Germany, our little town, which had in it a Soviet airfield, was bombed. My mother was injured in her leg. During that same bombing, a number of people were killed, and several houses destroyed.

On Tuesday, June 24, 1941, in the afternoon, the Germans entered the town. Before their entrance there was a small dogfight. The Soviets fled town on Monday without putting up resistance. At 5 o'clock, on Tuesday afternoon, the first German soldiers entered our houses. My mother who was wounded, lay on the floor out of fear from the bombardment; my brother, Moshe, of blessed memory, was lying down pretending to be sick. The five or six soldiers who entered obscenely asked for pork. We responded that we were Jews and didn't have any pork. We offered them buttermilk. But when they heard we were Jews, they rudely shattered the pitcher and left the house.

A day or two after the occupation, they had already published a proclamation in writing, in Ukrainian and German, that Jewish men and women from age 14 and older were obligated to report to the market square for labor, equipped with work and cleaning tools. Whoever did not present themselves – would be shot. Immediately, the Ukrainian police was organized, its recognizable symbol was a blue-yellow ribbon on the left sleeve. The women were sent usually for cleaning work and the men – for digging and field work on estate of Count Chodkiewicz, who had disappeared already by 1939.[3]

A few days after the occupation, a group of young Jewish boys and girls were arrested for being Communist members in the past.[4] Chaia Kipergluz,[5] Rivkah Ber, Freidel Rivitz,[6] Yenta from the Mandelkern line[7] (my father's sister).

Some of the people – about 200 – who were sent to labor, were directed to the property of the Count Liudochowski in the village of Smordva; Jews from the nearby villages of Boremel and Dymidivka were also taken to that same estate. The head of the estate was Volksdeutscher[8] Grüner,[9] a cruel sadist who would wake the men up many times at night and command them to run. The running required running down steps. During the descent, he would whip the runners with an iron whip so that the men would fall down the stairs.

[Page 288]

A special treatment in the estate was enjoyed by the blacksmith Hersh-Ber (the name of the family I don't remember).[10] He received bread to satiate his hunger which he also shared with others. He also occasionally succeeded in getting medicines. He held a position there until the liquidation and was killed after that in the forest. When someone got sick, he would take the person on as an assistant, so to speak, and this is how he rescued him, because it was forbidden to be sick.

A month to six weeks after the occupation, the Germans sought out members of the Polish parties. They imprisoned 10–15 Polish men and accidentally incarcerated the Jewish young man, Yehuda son of Mordechai Liberman.[11] The Germans misled the families of the prisoners and even accepted packages that were intended for them [from the families], but it became known, that in fact, they murdered all of them immediately after the arrest.

One night, in the early days, the Germans entered the house of the Jewish shoemaker Shlomo Kreimer.[12] He had a beautiful daughter, Rachel – who, upon seeing them, escaped through the window. As revenge for this, the soldiers killed the two parents. Their son, Zalman, who was [laboring] in the village of Smordva, burst out crying when the rumor of his parents' murder reached him. A German soldier who noticed asked him the significance of his crying, and when the soldier heard the reason – shot him to death on the spot.

In the first period, until the erection of the ghetto, there was not yet a severe shortage of food. Most of the families had a stockpile of food. In addition, items still existed which could be bartered with farmers. Somehow each managed, even though bartering was forbidden. Despite the prohibition, the Jews were going to the homes of farmers and farmers were coming to the homes of Jews to barter.

Immediately after the occupation, the Jews were ordered to don a white ribbon with a blue Star of David (Magen David) on the sleeve. A number of months later, in the fall of 1941, they were ordered to switch the white ribbon with a yellow patch on the back and breast. This obligation fell on children 12 and older.

In the fall of 1941, the Judenrat and Jewish police were established. As the chairmen, they appointed six earlier shopkeepers, all friends: Mordechai Litvak,[13] Chaim Yitzhak Kipergluz[14] – formerly chairman of the community (kehilla); as secretary, they appointed Katzevman, formerly secretary of the community and Mordechai Liberman,[15] David the kosher slaughterer (shochet) (the family name I don't recall);[16] and Moshe son of Yaakov Holtzeker.[17] In the police were Zelig Zider,[18] Shlomo Schechman,[19] Peretz Tesler,[20] Tzvi Gering.[21] There were another two or three others whose names, I don't remember.

The area commissariat was in the town of Dubno. In the fall of 1941 (the exact date I don't remember) an order was promulgated to the entire district – to supply 3,000 Jews as construction workers to the town of Rovno to build barracks for the army. The Judenrat in Dubno did not want to send the heads of families and decided to take men from all the towns in the area. In the small towns, they didn't know about the goal of the operations.

[Page 289]

Usually, in each operation, there were Ukrainian police who surrounded the small town and the Judenrat communicated the order – to supply a specific number of men. The Judenrat prepared the lists. From Mlynov, they took at that time about 50 men. Men of the Ukrainian and Jewish police went house to house searching for the men on the lists. Some of the men fled to the fields and surrounding forests. In place of those who fled, whose names were on the list, they would take anyone they came across. The arrest of the men was accompanied by crying and wailing.

The men were in fact transferred to Rovno for work. For about two months, news of them was received. After they finished the work, all of them were murdered and not one returned. In order to deceive the youth who were working there, some of them were purposefully sent home for a vacation. These, obviously, confirmed the knowledge that the men were in fact working and were even receiving vacations.

About a week after this roundup, a Hungarian military unit came, whose task was to confiscate grains, legumes, and flour from the Jewish homes. Of course, they didn't strictly follow orders and instead took whatever was at hand. This is how the Jews lost their reserves of food. In spite of this, until the last moment, the majority of town's Jews did not experience real hunger, since they always succeeded in meeting their food needs through barter.

That same fall there were two other additional operations: a Gold Aktion and a Furniture Aktion. During the Gold Aktion the Jews were ordered to bring all their silver and gold implements, dollars and jewelry. They all got receipts for the items that were turned over. After the Gold Aktion came the Fur Aktion – at the end of the summer 1942. After this, Germans arrived with several hundred Ukrainian police and with wagons and confiscated whatever they found – bicycles, sewing machines and regular furniture. The operation stopped suddenly. A whistle was blown, and afterwards some furniture still remained in the spots they had been set when brought out [of the houses] but which they hadn't managed to load on wagons.

Among the first victims, already in the summer of 1941, the Rav of the town was –Rabbi Yehuda Gordon.[22] He was summoned from his home by the Germans and held a number of days in prison before he was brought out and killed. It was said in town that the Rav knew how to speak German well and therefore they interrogated and tortured him for several days. Afterwards, he was taken outside town and killed.

Before Pesach 5702 (April 1, 1942), the Judenrat received permission to bake matzah. The baking was done in two places and following all the regulations [for baking matzah according to Jewish law]. The Germans did not take an interest in the source of the flour.

In the late fall months of 1941, the Judenrat issued a proclamation indicating that anyone who had a work certificate would not be taken into the ghetto (there was already talk that a ghetto would be established) and would be considered a productive element. Fictitious weddings started between young women and men who were consistently engaged in different kinds of work, and in particular, artisans, including those who worked on farms, who were mentioned above. Afterwards, commerce in work certificates developed. There were different types of certificates. The “best” type were the “iron certificates” that were given to the dentists, goldsmiths, decorators, and all different kinds of artisans, that the Germans openly engaged for their own personal needs.

[Page 290]

An example of the commerce in certificates: Perel Mandelkern,[23] wife of Yitzhak Mandelkern[24] (living today in Israel), traveled to Dubno to get this kind of certificate for her sister-in-law. Coincidentally, there was a roundup [Aktion] in Dubno and she was swept up and murdered. In that same operation, 5,000 Jews were murdered in a plot of empty land where the Jews had been assembled. One of them Leib Vinokur[25] (who lives today in Israel) – took a plank from a fence, attacked one of the German guards, stunned him and was able to escape and hide. Afterwards, he was with us in the forest.

In Mlynov itself, it was difficult to get these certificates, but trade in them flourished in Dubno. Even before the establishment of the ghetto it was forbidden for Jews to travel from town to town, and the trip to Dubno was therefore unlawful; in other words, the Jews traveled with Ukrainian farmers, disguised [as farmers], and of course with the agreement of the farmers. Every trip like this, therefore, was life threatening. On one unlawful trip, Yaakov Nudler,[26] who traveled to purchase arms for the resistance organization, was grabbed and killed, as discussed later.

The Ghetto

In April 1942, the ghetto was set up. It was confined to two streets, Shkolna and Dubinska. Permission was given to Jews from the other streets to bring personal belongings with them. Those evacuated individuals entered the homes of residents of the two streets just mentioned. Most made personal arrangements [which houses to join] and for others, the Judenrat organized the operation. Due to overcrowding, sanitary conditions worsened. In our living quarters – of two rooms – also lived our aunt, the family of Grandmother with two grandchildren (The kids of Yenta[27] had been killed already at the beginning of the occupation). In general, the density reached 7–8 people per room. The ghetto was surrounded by a barbed wire fence and had two gates guarded by Ukrainian police. The Jewish police generally accompanied those who went out for work. Apart from those who left for work in groups, no one was permitted to leave the ghetto.

The general feeling was that one should do whatever possible to be outside the ghetto. Those who worked on agricultural farms were subjects of envy by the ghetto residents. My sister, Fania, worked in a German office for road work and had a work certificate. The German soldiers who were in charge of this office were Austrian and treated her fairly well. Every evening she returned to the ghetto. While at work, she connected with a Polish family by the name of Veitschork from whom she got food. She also initiated a discussion with them about hiding in the event of the ghetto liquidation. The head of this family was a sentry for the roads.

Immediately following the establishment of the ghetto, the feeling prevailed that this was the prelude to the general liquidation. A number of youth, among them my brother Moshe Mandelkern, the brothers Shlomo, Yaakov, and Yitzhak Nekunchinik,[28] the police[29] Zelig Zider, Tzvi Gering, Peretz Tesler and Shlomo Schechman; Rachel Liberman,[30] Rivka Liberman,[31] Liuba Chizik,[32] Hannah Veiner,[33] Zelig Pichniuk[34] and others, tried organizing resistance.

[Page 291]

At the head of the group was Avraham son of Ben-tzion Holzeker.[35] Shlomo Nekunchinik[36] who lived before the war in an isolated home outside of town, had connections with foresters who had weapons. One of the Polish foresters promised him to supply arms to the Jewish youth. The youth gathered money to purchase weapons and prepared kerosene to set fire to the ghetto when the liquidation was announced in order to create chaos and provide an opportunity to flee. The group secured two rifles, that were held by Avraham Holtzeker. It was agreed that if escape to the forest was successful, those fleeing would try to reach the forests of Polesia[37] and the groups of partisans, whose existence had already been initially rumored. The members of the group were assigned different roles. Members of the group would meet almost every evening but did not succeed in achieving much. The weapons were hidden in the “tent” which stood over the tomb of the Rabbi Aharon from Karlin from the Stolin dynasty.

Those who were on a farm in the village of Karolinka[38] prepared two bunkers in the forest which had work tools and blankets. These bunkers were intended to serve those who fled the ghetto at the time of its liquidation. The following made it: my brother, Moshe Mandelkern, Shmuel Gruber,[39] and Yitzhak Mandelkern.[40] It is worth noting that the underground group was comprised of young people from the various youth movements, which had previously been active in town: “The Guard,” (Hashomer Hatzair), “The Young Pioneer” (HeHalutz Hatzair), and Betar –and a total unanimity prevailed among them. One fact stands out: proteges of the youth movements participated in the [underground] group apparently under the influence of the education that they received from the youth groups.

Further, in the late summer months of August /September 1942, rumors arrived about the ghetto exterminations in other small towns and cities. It was obvious that the Mlynov's turn was approaching and the fate of death of the town's Jews had been decreed.

In September, it became known that the farmers in the area were ordered to prepare a large pit in the valley between the two towns of Mlynov and Mervits, that was called Kruzhuk, a distance of one kilometer from the town. The first victims that were thrown into the pit were the brothers Fishel and Shlomo, sons of Nahum Teitelman[41] (who lives in Israel). They left the ghetto without permission. Apparently, they wanted to go to some village to hide. They were grabbed in the evening hours and thrown into the pit.

Before the liquidation, all the Jews who worked outside the ghetto on the various farms were ordered back to the ghetto. Some returned willingly to be with their families and some were brought by force by the Ukrainian police in a systematic fashion.

The Massacre

On the 8th of October 1942, the ghetto was surrounded by the Ukrainian police on German authority.

[Page 292]

With loudspeakers, they announced that it was forbidden to leave and periodically they brought groups of Jews and individuals, who were being returned to the ghetto from their places of work. Everyone understood this was the end. Men, women, and children went out to the streets. Panic and hysteria broke out. People prayed, cried, yelled, and huddled together with their families.

As it grew dark, the loudspeakers announce that they everyone had to go into their houses, keep the lights off, and anyone who left a house would be shot on the spot. Now and then the sounds of isolated shooting could be heard and occasionally the rattle of a police motorbike in the ghetto.

Translator's and editor's footnotes:

In the Valley of the Shadow of Death[1]

The Account of Fania (Mandelkern) Bernstein[2]

Translated and edited by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD, with Hanina Epstein

©

Escape from the Town

Our house was by the gate of the ghetto. My mother begged me to leave the ghetto. We knew that my brother Moshe was in a bunker that he had prepared near the forest by the village Karolinka.[3] My sister Yehudit joined him a week before the ghetto was surrounded. My mother pressured me to try any way to leave – to bribe a policeman or by begging a policeman for permission to get out. She also prepared a bundle with all different kinds of necessities for me, and even remembered to include scissors, thread and needles and the like. I approached one Ukrainian policeman; his name was Shafortyuk. I pleaded and cried for him to let me go. I promised him clothing and gold. Initially he swore at me and threatened me with his weapon. I begged him many times, until he told me to come in the evening when it was dark. He told me to bring him all the things I had promised and leave it in a bush by the gate. He also told me that he would give me an opportunity to leave and would shoot his rifle in the air, in order to disguise my exit and cover it up. Initially we thought we would leave together with my sister Rosa and my mother. But in the end mother decided she would remain behind so she wouldn't weigh us down.

I approached the gate with just my sister. About 6.30 pm in the evening, I brought the policeman the bundle I had promised him. A watch, gold coins, and nice boots. At first, he refused to let my sister leave. But he didn't have time to argue with us, afraid he might not get his loot. He opened the gate giving us opportunity to leave, shot [his rifle] in the air, and also showed us how to proceed, so that we would not fall into the hands of police. Initially we crawled a long way so that we would not be discovered. We wanted to go first to the Polish family Veitschork whom I knew before this.[4] We walked all night long even though the distance was not far.[5] We got to the home of the Polish family. The woman of the household wouldn't receive us and even told us to go away or else she would turn us in. Apparently, she was afraid to hide us due to the close proximity to the town.

[Page 293]

We continued, therefore, to another Polish family where my sister Rosa had previously worked. The family name I no longer remember. In this home, we hid for an entire day. The woman of the household told us that that morning all the Jews had been taken from the ghetto and murdered in a pit that had been prepared earlier. She also consoled us but asked that we leave the home that night because she would not be able to hide us. We, therefore, went back on the road with the goal of reaching the bunker of my brother. To get there, it was necessary for us to again return past the town and by the farm of the Count where Germans were. We walked all night. We were frightened by every shadow. We rested in a Christian cemetery. Towards morning we reached the forest. We didn't know the way to the bunker, but we knew where the farmer lived who had helped my brother and with whom he stayed in constant contact. He was a Pole. We reached his house okay with the rising sun. But he refused to receive us out of fear. He maintained that they were looking for Jews and were shooting anyone who helped them.

We continued to the forest and met some Jews. Among them was Yechiel Sherman[6] (today in Haifa), Golda, daughter of Aharon Asher Khait [the tailor],[7] and her sister (both perished), and others I don't remember. We were happy to meet other Jews. We told them there was a bunker nearby, but they didn't know where it was. Thanks to the knowledge of the bunker, they attached themselves to us. We wandered around for several hours. We met Henich (Hanoch) Gruber.[8] I knew that he and his older brother Shmuel were among those who created the bunker with my brother. He surreptitiously told me that he couldn't reveal the location of the bunker while we were still together with the large group, because the place was too small. It was difficult for us to break free from the group. Finally, in the evening, we got away, first myself, and afterwards, my sister. Hanoch Gruber brought the two of us to the bunker.

The Killing in the Town

I will pause here and recount what I heard from Ezra Sherman,[9] who escaped from the truck that was carrying people to the killing ravine and also what I heard later directly from farmers – about how the massacre was carried out. The Germans loaded the people on a truck and brought them to the pit. A plank was suspended over the pit. People were ordered to strip and one by one get on the plank. Before they did so, they were ordered to hand over their belongings to the policemen. Opposite the plank stood a machine gun that shot those crossing the plank with constant bursts. In the ghetto itself, Germans and Ukrainians stayed behind and searched house to house for valuables and Jews in hiding.

On the day of the liquidation, about 900 persons were massacred and buried in the large pit. Another several hundred people, residents of the nearby town of Mervits, who had been absorbed into the Mlynov ghetto, were slaughtered also that same day. Afterwards, during the next few days, another sixty-six individuals were seized, who had been rounded up by the police, and were brought out, killed and buried in a mass grave in the courtyard of the large study hall in the middle of the ghetto. The day after the liquidation, thousands of Ukrainian farmers from the nearby villages flocked in and plundered those belongings that remained in the Jewish homes which the Germans hadn't wanted.

[Page 294]

In the Forests of Mlynov

When we got to the bunkers, I found my brother Moshe there, my sister Yehudit, and the Gruber family: Shmuel [Gruber], his wife Charna,[10] their two children, and Hanoch the brother of Shmuel, the one who had brought us. Yitzhak Mandelkern[11] was also there, one of his six children, Gershon, his brother Moshe and his sister-in-law Malka Milbaski. The meeting with the people in the bunker caused agitation. They hadn't believed it was possible to successfully flee from the ghetto. I told my brother and sister about the loss of our mother with all the people of the ghetto.

In the same area of the forest there was another bunker, where David, the son of Yaakov Holtzeker,[12] the brother of Menashe, was staying, and another 3-4 people whose names I no longer remember. The distance between the two bunkers was less than a ½ km. At night they would go out to the homes of Polish farmers in the villages of Zofiówka[13] and Lodvykuvkah[14] and to the houses of Czech farmers in the village of Novyny Chaska.[15] We still had a few valuables that we brought with us and in exchange for them we received bread and potatoes. In the bunkers we arranged cooking stoves and we would cook at night, so that the smoke would not give us away. Also during the day we covered up our footprints as much as possible. We kept in constant contact between the two bunkers.

In the beginning of December 1942, one day in the morning, Menashe Holtzeker[16] came to visit. He stayed with us for an hour. Suddenly we heard shooting nearby. We realized that the neighboring bunker had been discovered. My brother, Moshe, yelled immediately that we needed to flee. I was barefoot and fled this way despite the cold. We all fled and left all our things in the abandoned bunker. While still fleeing, we saw the Ukrainian police approaching our bunker after wiping out the neighboring one. We realized that we couldn't remain in that area, and we left in the direction of the forest near Smordva. The distance directly there was not more than 13–14 km, but we wandered around during the night doubling the distance. From the farmers, we heard that in this area Polish partisans had organized, and they welcomed Jews and some escaped Soviet prisoners into their unit.

At the head of this unit were the brother Yugilevych brothers.[17] They were farmers from a Polish village who were going to be sent for forced labor in Germany. They evaded the trip to Germany and in retaliation the Germans burned their houses and all their possessions. They themselves managed to escape and join the underground. The Germans gathered two hundred Polish men as a transport to Germany. The Yugilevych brothers and their men set an ambush for this convey and succeeded in freeing it entirely from the hands of the German and Ukrainian escort. The first Jews who joined this unit were Moshe Kernitchuv, Simka Dvortchitz, Yitzhak Vaserman, Yaakov Buber and Yashkah Perlmuter, all five from Dubno.

[Page 295]

And a young man named Boris (Berel) and his brother Avraham, residents from Boremel, and others I don't remember. There also were about ten Soviet prisoners there who escaped captivity, most of them Georgians. The whole unit numbered about 30 people at that time, over time their numbers grew gradually.

The unit's presence in the forest was known to all the farmers in the area and they were afraid to encounter it. For that very reason we were drawn there. The unit set as its primary goal – to eliminate the heads of the Ukrainian villages in the area, which collaborated in operations with the Germans. They especially burned their houses and their possessions, thereby forcing them to be uprooted from their locations.

After a night of walking, we reached the forest by the village of Berehy where we rested during the day. We started looking for a fitting place to build a bunker. Along the way we equipped ourselves, from one farmer, with an axe and spade so that we could prepare ourselves a bunker. With great difficulty, we built a new bunker. One day we bumped into Jews who were also hiding in this area. These Jews didn't stay in direct contact with the partisan unit but, as noted, the very presence of the unit in the area turned it into a relatively secure refuge. Among those Jews were people from Mlynov: Meir Kwasgalter,[18] and his daughter Rachel (in Israel today), Aaron Nudler,[19] the son-in-law of Ben-tzion Polishuk, with a daughter and son, the brothers Shlomo, Yaakov and Yitzhak Nekunchinik,[20] the brothers Shlomo and Meir Schechman,[21] Hersch-Ber, the blacksmith mentioned earlier,[22] Golda and her sister from the Khait (tailor) family,[23] Natan Shiper,[24] Mendel Kwasgalter, and Avraham Drator from Dubno, with his sister Ema. A woman by the name of Kayla from the village Bokiima and a Jew by the name of Menusavsky from the village of Palcheh,[25] the family of Menusovitch, father, mother, with two children from Kozyn,[26] the Jew Butler from Dubno. There were other people whose names I don't remember. All of these people were scattered in many bunkers in the area, and each group tried to guard the secret location of its bunker. It is worth mentioning, that in the forest there was a well of pure water, that supplied water to the bunker inhabitants. According to farmers, this spring dried up in earlier years and only in this year did water begin gurgling…

For two months we felt relatively secure in the forest due to the “good” name of the partisan unit. Thanks to it, we received food from the farmers in the area who provided necessities, principally out of fear of partisan revenge, rather than willfully. Some semblance of life was created. Connections were made between couples; we would sing at night and hoped that we could hold our position until the end of the War and the victory over the Germans would arrive. The will to live was very strong – to continue to live in spite of it all.

One night when all the food was used up, I went out to obtain some food in exchange for the last ring that I still had with me. I went with my sister Rosa to the village of Klyn,[27] 6 km from our camp.

[Page 296]

It was rumored that evangelists lived in this village who didn't turn in Jews. We obtained a bottle of unrefined flax oil. It was a freezing night, and the way was very slippery. We walked very slowly but close to the bunker, no less, I slipped, and the bottle broke. I cried many hours from the heartache.

Hunted and Pursued

Over time, we split into small groups as much as possible to increase the possibility of escape in the event one of the bunkers would be discovered. Some of the people were based in section number 7 in the forest. I was in the group in section number 8. At the end of January 1943, a hunt was organized for the partisans and refugee families by the Ukrainian police under German command. Initially, section number 7 was attacked – which previously was considered the safest. The police advanced into the forest while firing. Eleven to twelve men, most from Dubno, were killed in that hunt. Also killed was [Itzhok], the son of Aharon Nudler, who was previously mentioned.[28] The bullet that killed the lad injured the hand of his little sister. Her father carried her on his back to a farmer's house by the name of Komarinitz, where the bullet was removed from the hand of the young girl. The farmer was an evangelist. By chance, there was a group of partisans remaining in that area who returned fire at the Ukrainians. The policemen withdrew from that area and moved to other areas.

After this pursuit, one group of the partisans decided to move to the forests of Polesia in the north to join with much larger groups of partisans. Another group stayed in place. Among the Jews who joined the partisans heading north – Devorjetz, Vaserman, and Avraham the brother of Boris.[29] The partisans decided that on their way north they would burn a large sawmill near Kremenets[30] that supplied the Germans with railroad ties.

One of the Yugilevych brothers had a son, a small boy, who was left in the care of a German woman who lived (among the residents) in a nearby village. He visited with her frequently and told her about the unit's trip north. The German woman informed the German authorities about it, which dispatched a large force to obstruct the path of the partisans. By the village Kamina Gorah,[31] the partisans were surrounded by about 25 German men. They held their position a full day in battle, and almost all were killed while bravely taking down many Germans. Avraham[32] and another partisan who was not Jewish managed to escape and ultimately reach the partisans in Polesia. Avraham returned with his unit to liberated Rovno in the beginning of 1944.

In hiding near the village of Semiga[33] was a family – two parents and a sister–of one of the young Jewish men [Aizia Wasserman][34] who had joined the group of the Yugilevych brothers in its trip north. The family hid with a Polish farmer. When the group arrived near the village Semiga, the young man went to visit his family. His desire to visit his family had been one of his motivations to join the group [heading north].

[Page 297]

The young man arrived at the farmer's house at night and asked if he could see his parents. The farmer told the young man that the members of his family fled that same day to the forest, from fear of the Germans who were known to be coming to the area, and indeed were grabbed and murdered by the Germans. The young man interrogated the farmer about the details of the event and also the fate of the family's belongings that they had with them. During the interrogation, he felt that the farmer was confused and hiding something. He thus started up with threats and punches. In the farmer's family was an old man – the farmer's father-in-law. The old man told the young Jewish man the truth about what happened. The Jewish family had many valuable things and they were turning over some of them to the farmer in stages. The farmer decided to get rid of the Jews and dispossess them. He therefore told them that their presence with him was known to the neighbors. There was no other choice but to leave for the forest. He suggested they accompany him. He took work tools to dig a bunker and brought them to a specific place as if to fashion them a hiding place. There he killed them and buried them. The old man said that this contemptible, murderous deed does not give him rest and interrupts his sleep at night. Taking revenge for his family, the young man killed the farmer, his wife and his son. The old man, of course, he left alive. (This story is also included in the Memorial book for the community of Dubno.)[35]

One morning during the month of March 1943, early in the morning on a rainy day, our bunker was attacked suddenly by Ukrainians. In this bunker was only –me, my brother, and my two sisters. The Ukrainians yelled at us to come out or they would obliterate us with a hand grenade thrown into the bunker. Or, they assured us, if we came out of our own free will nothing bad would happen. The attackers were Ukrainians from the Bandera men,[36] who had also formed a nationalist underground that was both anti-Soviet and anti-German. They began to remove the roof of the bunker. We had no weapons. We hesitated to leave. Some were begging for their lives. My sister Rosa decided to go out first and she was shot on the spot. I went out and demanded to know why they had shot my sister. They claimed that they had shot into the air and she had been wounded by accident. The exit from the bunker was such that only one person was able to leave at a time. When I came out, they told me to flee and they would not do me harm. After me, my brother Moshe exited, and begged the attackers not to shoot him in exchange for which he promised to reveal buried valuables that he hid in a nearby place. They believed him and didn't hurt him. He didn't have any buried treasure, but he hoped that along the way to the treasure he would succeed in breaking away and fleeing. And indeed, he succeeded. We scattered in every direction and, only after the attackers left, did we gather together again. My brother, Moshe, found my sister Rosa severely injured. We brought her into the bunker. Since we didn't have a doctor or bandaging, she died after a day of great suffering. We buried her in a section of a cemetery where six other Jews were buried, some [who died] from wounds and some from weakness and illness.

Since then our confidence was completely undermined. In the forest, the military sorties of the Banderites grew, who desired at any cost to exterminate the remaining Jews – in part from hate and in part so that no witnesses of their crimes would remain, in light of the danger posed by the approach of the Soviets.

[Page 298]

Among the group of partisans who were pro-Soviet, a quarrel broke out. Some of them wanted to join the unit of the Bandera men, among them Georgians, Armenians, Khazars, and other minorities. The commander of the unit was against this – a Russian named Philip. The group as a whole gathered in the home of a White Russian[37] forester by the name of Ostap who, on the one hand provided hospitality to the partisans but, on the other hand, maintained a connection with the authorities and informed them about the movements of the partisans in the area. The partisan units were adding different people all the time, especially escaped prisoners. During one of the disputes, the leader Philip was murdered. Two weeks after the assassination, the forest was surround by Germans who arrived there following the snitching of the forester, Ostap. He informed the Germans the partisans' place of encampment and the Jewish bunkers. On the other hand, he informed the partisans and the Jews about this hunt being prepared– in order to remove the suspicion that he was a snitch. All the Jews left the bunkers and tried to find hiding in the dense brush. The partisans did not leave their places, relying on their guards to successfully warn them of attacks.

When the Germans arrived, they detected the partisan guard and killed him. When the other partisans heard the shots, the men returned fire and retreated. Myself, my brother Moshe, my sister Yehudit and the Gruber family – hid near a spring in a place of dense undergrowth where there were no trails. We decided to remain there during the day and at night to return to the bunker. About 6 am in the morning, my brother told me to go up on the hill to see what was going on in the area. I saw two armed Germans approaching towards us. I immediately ran back to alert our people. Shmuel Gruber went up to check and to verify if indeed they were Germans coming. They saw him, shot him and wounded him. He fell and the Germans took him wounded with them to interrogate him. When we realized this, we all ran in single file in the opposite direction. Along the way we bumped into a group of Jews from a neighboring bunker. We told that them the Germans were on our trail and they began to run with us. In this group were 8 people, among them my future husband David Berenstein. Along the way we saw the Germans from a distance but they didn't notice us.

When we returned to the bunkers in the evening, we learned from farmers in the area, that the Germans captured Gruber alive and wounded, and that they discovered a bunker with 13 Jews, and also captured them alive, and took them for the purposes of interrogation. Among these 13 Jews, was a Jew by the name of Fishbein, a refugee in Dubno from the center of Poland. With him was his wife, a young boy and his sister-in-law – the sister of his wife. He asked the Germans to relieve himself and succeeded in escaping. He reached us and told us what had happened to the group.

[Page 299]

From that point, our terror and feeling of danger mounted. We decided that we needed to change where we were staying. Yitzhak Mandelkern suggested returning to the forest around the village of Uzhynets' and Karolinka on the assumption that there were not Jews there for some time and that they would not search for us there. We knew already that the Russians were advancing and we needed to hold on until their arrival. In any case, the news from the front gave us much encouragement in our fight to survive.

At that time, a group of escaped prisoners – comprised of minorities – united with a group of anti-Soviet partisans from the Bandera men. With the escaped prisoners was one local Jew, who had earlier joined them, and they included him thanks to his possession of weapons. His name was Yaakov Buber, a man from Dubno, who was previously mentioned. “His friends,” who joined with the Banderites, treated him decently – and advised him to go to the Jews hiding nearby, since they knew that the Banderites would likely kill him. They left him with his weapon and added a single hand grenade. He therefore had a rifle, a pistol and grenade. He came to us and informed us of the danger to be expected from the Banderites. This event hurried our heading to the forests of Uzhynets'.

The transition to the Uzhynets' forest was not an easy operation. We needed to pass the village of Berehy, which was near where a large German force camped. We needed to pass there out of necessity due to the bridge there. There was also reason to assume that the bridge was guarded by the Germans. We thought therefore about fording the river. Not all of us knew how to swim. There were also children with us. We calculated and prepared, waiting for a dark night when it would be easier to cross.

Translator's and editor's footnotes:

Ceaseless Wandering[1]

From the pen of David Bernstein[2]

Translated and edited by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD, with Hanina Epstein

©

One of the days at the end of May 1943 towards evening, we were in area 13 on a hill with Yaakov Buber, with my first cousin Belumah Bernstein (now in Russia) and with another young man by the name of Chuna, whose family named I don't remember (he lives today in Netanya). We went down to the spring to get water. When we descended the hill, we saw 6 armed men. We stopped, hid and they passed close by. We continued towards the spring. Along the way there were other bunkers of Jews. We decided to enter them and to warn them about the men we encountered. This was in section 9. During our conversations with a number of Jews, we heard Ukrainian voices. The Ukrainians had discovered a young Jew sleeping in a bunker and they were letting each other know. They got closer and it became apparent that the Ukrainians left him without harming him for the time being. We continued going to the bunker where, among others, was my present wife Fania. We approached and called for the people to come out. We spoke to them for a number of minutes and agreed that, upon returning from the spring, we would pass their way again.

[Page 300]

On the way to the spring, we had to cross a trail in the middle of a dense woods. We approached the trail and Buber suddenly decided that he felt grave danger and didn't want to continue. We didn't succeed in convincing him and we turned back with him. We approached instead a swamp nearby to get a bit of water even though it was dirty.

Along the way, we met a Jew from Dubno by the name of Butler. We asked him where he was going. He responded that he was going to the village Churtz[3] to a Polish acquaintance to ask for food. We got near the swamp and suddenly heard shooting from the direction that Butler had gone. We returned to the bunker where Fania was, to which we had promised to return. We stayed there outside the bunker convinced by a feeling of danger. We decided to leave that location the following day. Suddenly my cousin Bluma saw, from several hundred meters away, someone ducking down and aiming his rifle at us. We hid in the dense woods. We heard a thundering of men and shots at us from all around. We felt that we were being targeted by the attackers, so we wouldn't succeed in escaping; We also heard branches being broken by them. Next to me was Fania, Belumah and Chuna. I told them to wait until I tried crawling to find a way to escape. I suggested fleeing in fact in the direction from which the attackers were coming, on the assumption that they were actually heading towards our location, and we would thereby succeed in evading them. I told them to take off their boots so that they would not hear us, and I gave a signal at the moment that appeared to me best for bolting in the direction from which the attackers were coming. We heard much shooting. We thus didn't run in a straight line, but in a zigzag, to evade the bullets. In the meantime, it got completely dark. We ran for a long time without knowing how long we ran. We ran several hours, apparently a long distance, perhaps tens of kilometers, until we felt that we had completely left the forest and had become visible to those going by, if we encountered anyone. From a distance, we still heard grenades explosions and the fire of automatic weapons. We concluded that all those who had remained in the location from which we fled, were tragically killed. In the meantime, hard rain started to fall.

Slaughter

Towards morning, we decided to return to see if despite everything someone remained alive. Fania's brother, Moshe, had been there, and her sister Yehudit, and she wanted to return whatever the cost. We thus returned slowly with extreme caution. Suddenly, we heard voices of our Jewish friends, seeking one another. The first one we found was Meyerson from Dubno wounded in the chest. He begged us to be shot to end his suffering. He died on his own after about a half-hour. Afterwards, we met all the other survivors, among them Yehudit, sister of my wife, Fania, who succeeded in sheltering in an abandoned house in the forest under a crate. She was 12 years old, small and thin, and thanks to this, succeeded in hiding under that very crate. David Holtzeker[4] explained that Moshe, the brother of Fania, was taken alive by the Ukrainians and they killed him. He also saw how they killed a man from Mlynov, Meir Schechman.[5] Among the others who died in that same attack there were:

[Page 301]

Shlomo Nekunchinik,[6] Charna Gruber [née Goldseker],[7] whose husband Shmuel was killed earlier, their two children, ages 5 and 7, survived with Hanoch Gruber – the brother of their father, and they perished after this.

One bunker further way, which was named for one of its builders, the Jew Teler from Dubno, was not discovered by the Ukrainians and its people remained alive. As an aside, this bunker really excelled in being well-camouflaged, and its people believed that it was impossible to discover. Those there were: Yitzhak Mandelkern and his small son Gershon, Avraham Dratver[8] (today in Holon [Israel]) and his sister Emma from Dubno (today in Kibbutz Maale Hahamisha [in Israel]), Malka Hamilboskah – sister-in-law of Yitzhak Mandelkern, and Teler mentioned earlier. A young woman of 17 years old was there who woke in the night screaming – because a man who was then with them – she saw him dead. She was stricken with hysteria, and it was hard to keep her quiet. The man, indeed, died afterwards that very night, in the incident described above, when he visited one of the bunkers (apparently an experience of telepathy).

We Went to a Different Forest

The following day, the group of the remaining survivors decided to leave the forest. We gathered 13 people[9] – Fania, Yehudit, Yitzhak Mandelkern, his son Gershon, Yaakov Bubar, Chuna, Avraham Dratver, my sister, Emma, Malka Hamilbosky, Moshe – the brother of Yitzhak Mandelkern, Belumah – my cousin, Rachel Kwasgalter[10] and myself. Yitzhak Mandelkern led the way. We walked all night. We got to a small woods by Berehy towards morning. We stayed during the day in the woods and watched the movement of Germans in the area. At night we continued again and needed to cross the Ikva River. We saw a number of small dinghies and an isolated house. I suggested that the group hide in a cornfield. I approached the house, knocked on the window. The farmer fearfully opened the door. I was dressed with a German jacket and Spanish hat (which apparently had been lost by one of the volunteer Spanish soldiers who were with the Germans). I told the farmer that I was one of Bandera's[11] men. I also had a pistol which I pointed at him (the Banderites were pursuing Poles at that time). I told him that I was moving Polish prisoners. I demanded he give me a key to one of the locks on the dinghies. I also punched him to instill fear, and I warned him not to leave the house for an hour, or he would be shot. I waited until he went to sleep. He promised me not to leave his home until morning. I got a bundle of keys from him to all the dinghies there. We traveled in one dinghy via a couple of trips, 3 persons per time. The last one transported me. When we finished the crossing, I took the dinghy up on our shore without returning it to its previous place, so that the farmer would not be able to pursue us. The farmer also could not easily use the other dinghies since the keys remained in my possession. We continued on our way in the direction of the villages of Uzhynets' and Karolinka.[12] Along the way we got lost and walked a great deal further.

[Page 302]

We got to the area of these villages towards morning, though we wanted to reach the forest while it was still night. We hid during the day and felt too much movement around us. The following night we went to the village Karolinka which was populated by Czechs and therefore less dangerous to us. In that location, we dug a new bunker. At night we went out to the houses of Czech farmers. We appeared like Banderites and demanded food under threat of weapons.

One time, we took from one farmer: women's clothes, a small crucifix and identity documents for a young girl. I gave the documents to my cousin, Belumah, who didn't have the appearance of a typical Jew. She managed to get hired for work by a farmer and this also made it easier for us. Actual Banderite men came there but they didn't realize that she was Jewish.

The forest there was smaller and less dense, and we feared all the time that we might be discovered. We thought about perhaps moving north to the forests of Polesia and joining with the Soviet partisans there. During that same time, the Banderites distributed leaflets in the area, calling on Jews in hiding to come out of their hiding places and join them, since at this time they had already begun fighting against the Germans. This was a trap to eliminate in this way the last Jewish remnants. They caught one Jew from Dubno and convinced him that in fact they intended to help the Jews. This Jew believed them and revealed to the Banderites the hiding place of a Jewish family by the name of Sodovitzki – a man known from the community of Dubno. The murderers grabbed his wife and daughter and murdered them. Sodovitzki turned himself in after that begged that they kill him. The Banderites killed him and the Jew who showed them the hiding place.

One time I was sick, covered with sores, and I needed a warm bath. I went with Fania to a Czech farmer to beg him for the opportunity to bath in his home. We discovered that hiding with him were several Jews from Mlynov – Koppel Messinger[13] (now in the United States), Avraham Shek[14] and two other sisters from Dubno by the name of Hochberg. A Czech woman who was married to a Ukrainian came to the farmer's house. I realized that the woman was liable to snitch on us. Indeed, that same night Banderite men came to the threshing barn where the Jews were hiding. Avraham Shek was killed, Koppel Messinger and two Hochberg sisters managed to escape in the darkness.

Admist Czechs and Poles, Jews Are Saved

In the meantime, winter 1943–44 approached. We were able to arrange for Yehudit to attend to sheep, goats and geese with a Czech farmer by the name of Miller in the village Boyrica.[15] To avoid being discovered, we stayed in the bunker only at night; during the day we walked on paths that other people used, so that that our footsteps alone wouldn't stick out in the snow. We left various things in the bunker in order to check if someone had visited it during the day. One night we returned and were convinced that people had been there. We decided to leave again. Malka Hamilbosky, Dratver and his sister Emma, Yitzhak Mandelkern with his son Gershon – found a hiding place with a Czech farmer.

[Page 303]

Yaakov Buber met the two Hochberg sisters and made arrangements with another farmer. Moshe, the brother of Yitzhak Mandelkern, hid with a farmer, but was discovered after 3 days and killed by Banderites. Rachel Kwasgalter also found shelter with a different Czech farmer. Fania, Chuna and I did not find a hiding place.

We were aware of an abandoned Polish village, Pańska Dolina, whose residents left from fear of the Banderites and went to live in Lutzk. In the village there remained only a handful of young armed Poles, about 20 of them, to guard the property. They were fortified in four houses by the main thoroughfare. These Poles guarded their village with the acquiescence of the German authorities. We heard that a number of Jews were hiding in the abandoned houses (with the knowledge of the Poles who guarded the village). On the way to the village, we decided to check on the wellbeing of Yehudit, Fania's sister. We arrived at night to the farmer's yard and went in to sleep in his threshing barn. Early in the morning the farmer came out to work. Fania went out towards him and told him that she was the sister of Yehudit and asked about her. The farmer told Fania that two days earlier Yehudit was taken by Banderites. Fania began to scream and cry – why did he turn her over and not protect her? He softened up and asked her to go to the threshing barn, because in another 10 minutes Yehudit would appear. Indeed, Yehudit arrived and explained that in fact they had snitched on her, but the farmer sent a neighbor to the field to warn her and at night hid her well and decided to hide her to the end. He told the Banderites that she had fled to the forest.

Fania felt that Yehudit was withholding some secret from her. Finally, on the condition that the secret not be revealed, she explained that she was in a hiding place on the farmer's grounds with two other Jewish families. Brayer[16] and Brodman[17] – whom the farmer had hidden from the beginning of the eradication. This was revealed to Yehudit incidentally when the Banderites were looking for her; at that point the farmer hid her with these families. The families numbered 6 people, including a son who was 4. For their security, the members of the family wanted Yehudit to go with us, but since we didn't have a hiding place, we were not able to take her with us and we left her there. Thus, she stayed with this same farmer until the liberation.

When the Germans retreated, the Czechs left the village and, for the security of those hiding, put a covering of wood on top of them and scattered livestock manure on it. To the bad fortune of those concealed, German soldiers settled in with horses to the threshing barn where they were hiding. The men stood and with their backs supported the covering for 72 hours without it caving in! As to the fate of this family – the boy and his father died a short time after the liberation in the town of Rovno, the father from tuberculosis and the son from meningitis. The woman was pregnant when leaving the bunker and after the death of her husband married his brother, who had returned from Russia.

From the grounds of Miller, where Yehudit was hiding, we headed towards the village of Pańska Dolina , after hiding during the day with Miller.

[Page 304]

We went out on the way again at night and reached the village of Lebnovkah[18] – about an hour of walking from the grounds of Miller. It was a very cold night and a snowstorm occurred. Due to the storm we were not able to continue walking. We felt that we were going to perish on the way and it was imperative for us to find shelter. We approached a house, knocked on the window and presented ourselves as Jews. It is worth pointing out that the residents of this village were also Czech. The woman of the home opened the door and permitted us to enter and to warm ourselves. It is hard to describe how much we enjoyed the warmth that prevailed in the home. The woman bathed her children. We envied her and wondered – if we would ever be fortunate again to have a warm home where we could wash in warm water and soap? The woman of the home introduced herself, her name was Kunshk and she told us that her husband was on guard duty in the village. She gave us warm food and requested we hide after this in the threshing barn because if we were discovered in the house, the Germans would kill the entire family too; but if they discovered us in the threshing barn, we need to claim that we entered there without her knowledge and permission. Due to the storm, we remained in the threshing barn until morning. In the morning the woman told us, that in the village they were saying that the Germans were going to come to confiscate the pigs near the holidays, and therefore we needed to leave immediately. We therefore went back on the road, even though we didn't usually move about by day.

In order to reach Pańska Dolina, we needed to cross the Dubno-Rovno road that had a constant, active movement of German military men. Obviously, our appearances and clothes would easily give us away. We crawled towards the road. We hid in a ditch with the goal of crossing the road by exploiting a break between vehicles. One by one we crossed to the other side of the road and finally succeeded in reaching Pańska Dolina. Due to the intense cold, most of us had a urinary tract inflammation, causing suffering and pain, in addition to being inconvenient and uncomfortable.

Upon entering the village, a wagon passed with a Polish young man sitting in it whom Fania recognized as a friend from a class in primary school. He also recognized immediately that we were Jews and directed us behind the house where a woman from our town was hiding, Leah [Liza] Berger[19] (now in Uruguay). We entered this house and we found Leah inside. She told us that the farmers from that place were in Lutzk and returned occasionally in order to pick up grain and other necessities for sustenance. She was of the opinion that there was a chance that one of these families would turn over their house to us on the condition that we guard their property, since the Poles generally did this willingly, thereby increasing the chances their property would not be robbed by the Ukrainians.

The plan in fact came to pass. We were granted a house like this, and we also had enough food to be satiated from the stock of goods and from the farm. In addition to us, other people from our town who were hiding in the same village were: Rachel Kwasgalter,[20] Rachel Fisher,[21] Freida and Leon Kupferberg,[22] the Malar family (the parents and daughter) from Dubno and others. Together there were more than 50 Jews from the different small towns in the area.

[Page 305]

During that time, Polish partisans were organizing and training in the area who subsequently crossed the Bug River to join the organizations of Polish partisans on Polish land. As mentioned, the local Poles were armed and guarding the village from the Banderite gangs with the acquiescence of the German authorities. The Germans therefore trusted these Poles and did not organize visits to this village. The Poles, on the other hand, leveraged this situation to organize an underground against the Germans. This was reasonable against the backdrop of the situation at the front, since it was obvious to the Poles that the Germans were going to lose the war and that it would be good for them to improve their standing in the eyes of the Soviets, who would arrive in the future, by [becoming] anti-German underground fighters. The Polish units, therefore, were being exchanged. In addition – and also against the background of the general atmosphere – they all were patient with the Jews who were hiding with them and were assisted by them in different kinds of work. One time a new Polish force which numbered 120 men came to the village. The Polish groups also carried out punishment operations against Ukrainian villages that were earlier active against the Poles. With the Poles was a Jewish baker named Micael from Lutzk, who lives today in Israel. The Poles were looking for a doctor and weapons. There were rumors that in the village of Noviny Chiskia[23] a doctor was hiding by the name of Grintzveig from Dubno. They asked that one of us volunteer to go with them to find and to secure the trust[24] of the Jewish doctor and to add him to their unit. I volunteered to go with them. They gave me warm clothing and a weapon and we left at night for the operation. This was a group of about 60 men. The main mission of the operation was the seizing of weapons from the residents of the surrounding villages and taking the same opportunity to locate the Jewish doctor. We succeeded in seizing about 15 rifles, principally from Czech houses, but we didn't find the doctor. Afterwards, it became clear that he was hiding in another village. The Poles appeared in disguise, on their hats they put red military decorations and spoke Ukrainian and Russian, so that the local residents would think they were Soviet partisans. This disguise was necessary not just for the Ukrainians but also for the Germans, so that it would not become apparent that Poles – especially those in Pańska Dolina – were engaged in unlawful activities, a time at any rate when the operations of the Soviet partisans were already known.[25]

During the operation, the Poles stationed men for observation, concealed in different positions along the roads. Towards morning, a sleigh with two armed Ukrainians approached one of the guards in an observation post, and it became apparent that one of them was an officer from the Bandera gangs, who was returning from a consultation with the officers in the village of Dobryatyn.[26] The Polish guard ordered them to raise their hands. The Ukrainian officer thought, apparently, that there must be a misunderstanding and approached and brought out his pistol. The Pole shot into the air. Upon hearing the shot, other Poles gathered and took the Ukrainian officer into captivity. He still thought they were Soviet partisans and he explained that in his gangs there were also Soviet partisans.

[Page 306]

I sat in the wagon next to the officer. We all traveled in the direction of Pańska Dolina. The whole way we spoke Ukrainian and Russian. Along the way we continued to interrogate him. He revealed that his name was Strodov and that he and his gang were fighting only Poles and Jews. He also gave up the location of his gang and its headquarters. When we got to Pańska Dolina, a Pole sat by me and said, “Now, it is okay to reveal,” and he said to the Ukrainian – “We are Leechim[27] from Dolina” (“Leechim”- a derogatory name for Poles by the Ukrainian nationalists). I added, “They are Leechim and I am a Yid, and now is your opportunity to live in the skin of the Jews who are being taken out to slaughter.” The Poles beat him with heavy blows while giving a mocking rendition of the Ukrainian anthem.

In Pańska Dolina that same day, a group of men happened by, apparently senior officers from headquarters of the Polish partisan movement in Lutzk. They organized a quick field justice for Strodov and took him away to be killed together with the coachman. According to what became known later, this Strodov had earlier been in the German police in Mlynov and the surrounding area and he was among the head of the death squads that liquidated Jewish ghettos in the area. After several days, a punishment brigade[28] went to a village in which the gang's headquarters was located, whose position Strodov had revealed. In this operation, the Poles succeeded in capturing and wiping out 6 additional Ukrainian officers.

After approximately two weeks, while the Polish force was still in the area, a group of Germans passed on the main road nearby – while the Poles were drilling in the field. The Germans noticed that these men were armed and thought, apparently, that they were Banderites preparing to attack the Poles in Pańska Dolina and opened fire on them.[29] The Poles returned fire but successfully escaped within 10 minutes. The fire was only to give cover for the escape. During the exchange of volleys, one Pole was mortally wounded. The Germans grabbed him, but he kept up his Ukrainian charade and his life left him without revealing the fact that they were Poles. He was brought to Mlynov and his heroic stance we learned about afterwards from the people of Mlynov. After this skirmish, the Poles left Pańska Dolina, but after a few days other Poles arrived in their place.

In the meantime, the front was drawing near. One day a Hungarian officer appeared and requested permission from the Poles for his retreating unit to pass by. These were Hungarians who fought on the side of the Germans but already during this time were trying to evade their duties and desert the front. This group was trying to reach the Hungarian border. In this unit was also a unit of conscripted Hungarian Jews, part of a Hungarian “labor army.” The Poles permitted them to pass. The Hungarian Jews that came to the village were feeble from hunger and exhaustion. We gave them bread and tried to convince the Jews to remain with us, because here with us was a more secure place; for if they continued with the Hungarians, they were liable to fall together with them into Russian captivity.

[Page 307]

It is worth noting that only two Hungarian Jews remained with us, and they did indeed survive. The rest remained faithful to their Hungarian superiors and continued with them. It is not known what fate befell them.

Hardships After the Liberation

The Russians!

On the 5th of February 1944 in the evening, they knocked at our windows. We got up and opened the door. The men identified themselves as Russian scouts. They were 15 calvary riding on horses and among them was a sergeant major by the name of Falki. When he entered he asked, “Who are you?” We responded that we were Jews. He got emotional; he turned to us in Yiddish and said that he had traveled over a 1000 kilometers and he not yet met Jewish survivors. He asked what we needed. The following morning a Russian unit entered. Falki came with them and with him was a Jewish captain named Boris Shalkubar and a Russian captain by the name of Volkov, and they brought the best stuff for us. Volkov had taken the Jewish boy Sherman[30] with him and attended to all his needs and cared for him like a father. Sherman accompanied Volkov all the way to Germany; there at the front Volkov was killed during one of the bombardments and Sherman reunited with his brother Yechiel,[31] who along with several other Jews was staying in Mlynov at the time (the two of them live today in Haifa).

When the front reached our area and the battles were raging, we found it necessary to advance behind the Russian lines, out of a fear of a temporary retreat, that can happen during a battle – and that the Germans would appear again, even if their days were numbered. We therefore headed to the town of Lutzk, where Jewish survivors had gathered from many different places – from bunkers in the forest and in the villages as well as Jews holding Aryan papers. We reached Lutzk the day of a Red Army holiday. That same day, the Germans started an offensive across the Styr River. We saw a strong movement [of troops]. It became obvious the Soviets were leaving the town, in other words, temporarily retreating. We asked the Soviet officers and soldiers for permission to join them, since we were Jews and must not fall into German hands a second time. They steadfastly refused us and did not permit us to go with them.

Therefore, we decided to go by ourselves – a group of 15 Jews – towards the city of Rovno.[32] We went on foot. The way was dangerous since there was a movement of a fighting army in the conditions of a front. We walked at night. It was a bitter cold night. In one village, we wanted to take a short rest. We entered the grounds where we saw Russian soldiers. A Russian captain came towards us with a pistol in his hand. We told him we were Jews who were heading in the direction of Rovno; we were cold, wanted to rest and were afraid to move at night because of the Ukrainian gangs. The officer said to us, “I don't care who you are; if I let you to enter, I will have to guard you and I will not be able to rest; therefore get out of here, and if not, I will shoot you.”

[Page 308]