|

|

|

[Page 207]

To My Little Town

by Eliyahu Gelman[1], Netanya

Edited and translated by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD with Hanina Epstein

©

|

My little town, I will hold you from afar days and days The image Of father who perished and alongside his gravestone, in the cemetery [saying] “Kaddish”[2] In a choked voice a son is praying (Woe to me — your gravestone is shattered from before and is no longer) Mother's appearance for the sake of her children is sacrificed day by day [so too] the appearance of brothers, sisters and children the whole community of Israel (alas – they are no longer living, with no trace and no marker for the grave)

Time lengthens from the days of their wounds “there used to be a little town” 12.10.65 [October 12, 1965][4] |

Translator's and editor's footnotes:

by Shmuel Mandelkern,[2], Tel Aviv

Edited and Translated by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD., with Hanina Epstein

©

In those days,[3] when the Zionist idea was not widespread, even as a presumptuous dream by the Jewish people in the Diaspora (golah), and the idea was especially considered not kosher (terefah) in the eyes of the orthodox stratum – then, in that period, there might be one [Zionist] in a town and literally two in a family, of course in the small towns. But in Mlynov there were four boys, who were drawn, God save us, to the Zionist idea.[4]

[First:] The writer of these lines was captivated by Zionism following his studies in the yeshiva and with the Rav, Rabbi Moshe Avigdor Amiel,[5] then the Rav and head of the orthodox secondary school (mesivta) of the town of Swieciany where he was Zionist (towards the end of his life he was chief rabbi of Tel-Aviv-Yaffo.) Of course, all his students, about 450 young men, held fast to the Zionist idea.

[Second:] My friend was Yermiyahu Maisler,[6] son of Mr. Mendel the writer (schreiber) from the Jewish community of Mlynov: He held fast to Zionism after being a student of the Rav Yitzchak Yaacov Reines[7] (who merited a number of roads in Israel being named after him), [and] was the Rav and head of the orthodox secondary school (mesivta) of the town of Lida, in the area of Vilna.

[Third:] Berel Lovshis, son of Aharon the blacksmith.[8] He also studied in the study house (kloyz)of Rav Malis[9] from Vilna, and it is no wonder that one who studied in the cultured city of Vilna, embraced the Zionist idea.

[Fourth:] Last but not least, “the Benjamin” [i.e., the youngest][10] that was in the group, the poet Yitzhak Lamdan, then young, weak, pampered by his family and especially his father, Rabbi[11] Yehuda Leib Lamdan, who protected him from all harm. As evident by his literary future, it was as if he was born with Zionist idea.

The activities of the four boys mentioned above relied on activities for Keren Hakayemet [Jewish National Fund] which was relatively speaking “very limited.” And since the minor activities didn't satisfy us, we sought out bigger and more substantive Zionist activities.

Sending a Pioneer to the Land of Israel

One operation like this, the idea of which totally captivated us, was to actually send a young person from Mlynov to the Land of Israel, in the capacity of a pioneer who would go ahead of the group.

[Page 209]

We choose for this good deed (mitzvah), for various reasons, Yaakov-Yosi Gruber, son of Mr. Yisrael Mordechai's [son][12] from Mervits, one of the Hasids “burning with passion” for the Maggid from Trisk[13] who was from a very venerated and famous family.

Why did we choose specifically this Yaakov Yosi and not one of us, to be the first pioneer from our town in Israel? – the choice was for the following reasons. Yaakov Yosi was a young man not from the group of friends. He did not dress nicely[14] and this stemmed from the pressing [economic] situation of his father. For the same reasons he didn't continue in his studies among other things. Among our friends he was like “the gopher” [lit. luggage carrier] of the group. We would say that he was left in the dust behind the smart students, so to speak. Thus we planned to save him from the poverty of his father's house, and help him to set some sort of a goal in his life. We decided, therefore, that the best solution for him would be – aliyah to the Land of Israel.

And from talk, we moved onto action. Since we knew that aliya to the Land of Israel required specific preparation in order to pass the examinations that were set up then in Odessa, the place where all the immigrant pioneers had to take the tests, we thus began actual preparations implemented via daily lessons and instruction that he received from us.

Superficially, all was on track, but – there was a fly in the ointment [lit. a thorn in it]. In those days, when the livelihood of most of the small towns' population was under severe pressure, there was a small portion that was doing well, with no pressure – and this was the small industry of fabric makers, an industry that occupied for some reason most of the people of Mervits, which was close to Mlynov.

Mr. Israel [son of] Mordechai hoped one day to realize this respected livelihood, both because the young lad Yaakov Yosi was growing up, and when it came time, they would say he was a respected person and he would marry with a daughter of a good family who had a substantial dowry, and then he [Israel] would be able to realize his dream of establishing a fabric shop. To achieve this goal everything was in place, meaning – there was a groom…because he was 18 years old. A specific location for this industry was also already prepared. Thus, to carry out an operation like this [namely,] -- sending his only son to the Land of Israel, and robbing him of hope to better his situation-- involved much risk, if the matter were made known to his parents. For these reasons, each of us was truly afraid and didn't want the preparatory lessons to take place in his home. Casting lots determined that the intensive Hebrew school (ulpan) would take place in the home of Yeremiah Maisler,[15] son of the teacher in Mlynov. To avoid the evil eye, the place of instruction would be in the roof attic in the house of Mr. Mendel the writer (schreiber), a place that was designated for the chickens of Mr. Mendel. Each day Yitzchak Lamdan in particular would come to give him the required lessons. From time to time, we would gather in the attic, to listen to his progress in the studies. On occasion, we would even arrange examinations. If my memory does not deceive me, I was the only one who said that our effort was a waste, because he would not pass the tests in Odessa. The only one who had a positive opinion in this was Yitzhak Lamdan.

[Page 210]

Funds for Aliyah

After a substantial time and a complete winter, we met to solve the financial challenge to fund the travel expenses, a matter that was not easy in our circumstances then. We decided to turn to gentlemen, Zionist wheeler-dealers in the area, to bring our program to their attention and request financial assistance.

With respect to collecting funds we adopted a system – we took every opportunity that came to hand. For example, our friend Yermeyahu Maisler had a cousin of the family in Trovits [today Torhovytsia],[16] named Shlomo Fuksman, a senior clerk in the flour mill of Richter. He had two sons and an only daughter, and like children of the wealthy, they would lag in their studies, as it is written [in the Talmud, B. Nedarim 81a] “Be careful with the education with children of paupers since from them Torah will issue forth.”…Since Yermiyahu had graduated the Lida yeshiva[17] and had much knowledge in Talmud, and especially Hebrew, his cousin gave him an appointment as teacher and mentor of his children; in this way our friend Yermiyahu was popular and respected by the local youth.

And the following custom came first during joyous occasions in particular at weddings, when hearts were partaking fully in wine and all sorts of alcohol and food, they would donate favorably to all applicants for donations and charity (tzedakah) such as: helping the poor, bringing a [poor] bride [to the canopy],[18] visiting the sick and so forth. In the latter years the youth also exploited [this time] during wedding parties– among other opportunities – to gather donations for Keren Hakayemet. And we thus were the smart ones who saw what was going down, and we followed the advice of our friend Yermiyahu to capitalize on the eve of the wedding, that was going to take place in Trovits, for our goal. At the outset, we were confident in our success because of the participation of our friend Yermiyahu in the donations since he was known locally.

The Trip to Trovits [Torhovytsya]

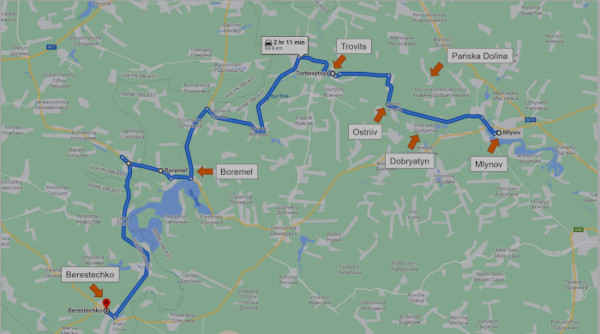

The first opportunity, during the winter days, in the first wedding to take place in the town, I, the writer of these words, and friend Yermiyahu took the mission upon ourselves. We rented a winterized wagon,[19] and went on the road, in order to arrive in time for the wedding. We made the following estimation: since the wedding meal began about 8 o'clock in the evening, and the fundraising took place, obviously, during the meal, as noted above, “when the participants in the meal were merry with wine”[20] – we were sure that we would arrive exactly on time, since our town of Mlynov to Trovits was a distance of 15 km [9.3 m], about a two hour trip at the time…therefore we decided to leave at 5 in the evening, in order to arrive before the time of donations, so that the local young men of the town could join us in this important Zionist fundraiser, since among them was Avramel Ackerman son of the well-known Rav Rabbi Mordechai Neta [Ackerman] z”l,[21] the sons of R. Meir Feldman,[22] and others.

[Page 211]

However, the distance between talk and action is vast… when we left Mlynov about 5 o'clock, and when we passed the town of Mervits, a small storm began, accompanied by large flakes of snow, and the storm grew bigger from moment to moment. The road was obstructed and we saw only a white surface in front of us, with no road, no sky, and with no sign of a nearby settlement…and this despite the fact that there were several villages along the road, like Stomorhy,[23] Dobryatyn, Ostriiv and others. We noticed another thing, [namely] that we were traveling and traveling but remaining in one spot with no possibility of continuing or going back. In truth, we had not anticipated endangering our lives, since we were wearing good winter clothing, but at the top of our concerns was the worry that we would be late for the meal, and after traveling in the chaotic storm for several hours, the sound of barking dogs reached us from afar. We realized that we were finally close to a settlement. We turned our steps towards the barking dogs, and we reached the town of Pańska Dolina (the valley of the noblemen) at 8 o'clock at night. The upshot was that instead of a typical trip of one hour, we traveled three hours…

When we saw a faint light that came from one of the houses, we didn't wait for an invitation; we knocked on the door and entered inside. By chance, the homeowner was the village head (muktar). We told him what had happened to us, and we asked for his help, to facilitate us to reach Trovits as quickly as possible. But our homeowner didn't hurry and began to change his tune (literally “sing a new song”).

“You say that you are from nearby Mlynov, your request is fine, but I don't believe you…” (due to the tense political situation, that prevailed then between Russian on one side and Austria on the other[24]). “I suspect you of being spies for Austria and your goal to spy out the area. Because it is not possible that young people from Mlynov don't know the way to Trovits, which is so close.” And furthermore,” he asserted “I have never in my days seen young people of Mlynov wearing such beautiful clothing” (since we were in-laws of the wedding party [and thus dressed for a wedding])…

Treating us like Spies…

As a government official (muhtar of the village), he believed he was obliged to act in an official capacity, and obligated to transfer us to the district seat of Dubno. We thus had to spent the night in the village jail, and in the morning everything or everyone would be restored to normal…

When we heard what he said we were furious: a: we would lose the fundraising opportunity during the wedding, and b: this was the key point, when they would bring us, as he said, to Dubno, it would be necessary to pass Mlynov, and suddenly the people of Mlynov would see us tied up. And then, obviously, an inquiry will start – what is the purpose of our traveling to Trovits, and there would be a significant risk that the whole “story” of sending Yaakov Yosi to the Land of Israel will become widely known.

[Page 212]

We, obviously, held our ground and asked him, literally with tears in the eyes, not to cause us this kind of shame, by bringing us the next day as prisoners past Mervits to Mlynov.

Our words apparently made an impression on him and he said, “One thing I'm able to do for you, in spite of the late hour, and that is – to call together the village committee to my house to take counsel on the matter and hear their opinion. He sent a member of the household to the committee, and we were sitting on pins and needles [lit. sitting on hot coals], because the time for fundraising was passing. After some minutes, some of village committee members appeared. The head of the village (muktar) introduced us to them by saying “the fish were caught in the net,” and he suspected us of spying. Their opinion was no different than his and emphasized the point that they never had seen youth from Mlynov so dolled up. The entire time I conducted the discussion and maintained that our words were truthful, that we were Mlynov young people and not spies. During the discussion, an idea came to me, and then the proposal to which they acquiesced. The proposal was: “If I list for them all the business men from Mlynov and Mervits, with whom you have business ties, in other words, from whom you buy all necessities and clothing, and to whom you sell your products, and the market days in Mlynov that you visit every two weeks, selling your horses and your cows, and buying from the men of Berestechko your winter boots and from the men of Chavlykah[25] your rustic furs – will this satisfy you that we are not spies?” After saying this, we saw a positive response in their faces and for their part they began to ask additional different questions about the men of Mlynov and Mervits, and in the end they asked us what we needed from them. When we explained that we were headed to Trovits, and we were requesting help getting there, they took us outside (the storm in the meantime had abated) and they pointed us in the direction, “Look, you can see sparkles of light in this distance, this is the town of Trovits – you can go safely along this road, and in another half hour you'll reach the area you are seeking.

And so it was. We continued on the way and after a bit of time we were in Trovits, near the house where the wedding was taking place. There we found all the Trovits youth outside, peeking inside via the windows, as was customary in small towns, waiting for our arrival and worried about our delay. When we arrived, there was great joy and before we had time to recount the detailed story of the our difficult trip, we decided first of all, because of the late hour, to carry out the fundraising among the wedding guests. The fundraising was a great success due to the participation of the golden youth of Trovits. [It was a success] from the perspective that no one refused.

After the fundraiser, we gathered together and told them the details of getting lost on the snowy roads and the suspicions of the Pańska Dolina village leader that we were spies and came to check out the area. Thus after succeeding in carrying out our mission completely and with success, we were very happy, and we spent all night in song and singing and it was like a mini Zionist evening.

[Page 213]

The Youth of Trovits

Among the youth, several stood out who didn't submit to the will of their parents' whose sole goal was “at age 18 the wedding canopy,” [namely] to make a good match with the daughter of a good family and to receive a hefty dowry, and ultimately open a store for herring, salt and more; and the main purpose to continue the tradition of the grandfather and parents. Among those who refused to continue in this faltering tradition was Avramel, son of the Rav [Ackerman], several sons of Mr. Meir Feldman, and their desire was to continue with their studies and leave the small town, and travel to places of Torah, like the Lithuanian yeshivas, the Odessa yeshiva, which was conducted by “Young Rabbi” (Rabbi Chaim Tchernowitz[26]) and even complete their education in Kishinev in the yeshiva Rabbi Tsirelson[27] and this was no small thing. But all these wishes encountered and were shattered by the parental wall, who objected: a) “how can I abandon my son to someone else's education?” b) “Heresy,” the reputation of agnosticism sticks like it came from heaven to those educated in the yeshivas mentioned above since they carry one towards Zionism. They realized that continuing education in Talmud, in Tanakh, and in Hebrew, is the start of the road that leads to Zionism, and, heaven forbid, the repudiation of God, by failing to wait for the redeemer and for the coming of the Messiah.[28]

In most cases the parents had the upper hand. When Avramel son of the Rav met us that night, he had identified a good [kosher] time to convince his father, the rabbi Mordechai Nute Ackerman, that the devil is not so bad, and that you can look [at Zionism] and not get hurt, and he invited me to visit in his house for an lowkey conversation with his father at two in the afternoon of the following day. I asked the group about the views of the spiritual leader, the Rav, of Zionism, Hebrew and more; they answered that their Rav was mostly neutral and in my eyes this was a significant accomplishment by the local youth, since most of the rabbis in the small towns of Ukraine were strongly against Zionism, Hebrew culture, and all things Hebrew. I did not accept the opportunity to visit mentioned above very heartily since there were rabbis and students of Talmud among them whose goal was to trip up the youth in [their] knowledge of Talmud and so forth. But out of mutual respect, I agreed to the visit.

In the House of Rav Ackerman

On the following day, at exactly two o'clock, I entered the house of the Rav and found him in a well-ordered room. He engaged me respectfully, befitting an honored guest. His personality was pleasant,[29] he was clothed elegantly[30] and organized meticulously. Everything about him said “honorable.” He received me with a big “Shalom Aleichem” [Peace be upon you], invited me to sit and asked me. “What's on your mind?” I told him that yesterday I came to Trovits for a short visit. Obviously, I did not reveal the purpose to him and he didn't ask. “My intention had been to return to Mlynov today,” I said to him, “but since his son Avramel invited me to his house, I made good on the saying, 'one may not decline the request of a great man.'”[31]

[Page 214]

Since Avramel was really short in stature, the Rav answered me half in jest [in Yiddish]: My son Avramel “is just a small boy,” so how are you interpreting “one may not decline the request of a big man”? I answered him [explaining that] the sages didn't mean a big person from an athletic perspective but a person great in wisdom and thus [moreover] “the acts of fathers are a sign to the sons.”[32] And he ended [the conversation with]: “Good.”

The conversation continued for about two hours. We talked about this and that and the key matter of interest was the study methods in the Lithuanian yeshiva. “What is the difference,” he asked me, “between a boy's study hall, one who is studying between the walls of the study hall in a small town and the students of a yeshiva in Lithuania?” Similarly, he was interested in the lives of Lithuanian Jewry, their situation, livelihood and so on. And he especially pressed me to explain to him how a young lad, who has no supervision from his parents in a foreign location among hundreds of teenagers, what impels him to continue his studies? With this question, he reminded me of a Russian proverb which says, “No father, no mother, there is no one whatsoever to fear.” On this point, I answered him that: first, there are some teenagers who have a diligent character; this type of youth is capable of coming at 8 o'clock in the morning to the “yeshiva”[33] and to sit until one in the afternoon and not move from his spot, and they pull along with them another large segment of the students, and are the “envy of scribes” [i.e., because they can sit so long without moving]. Second, in the study ulpan during the entire time there is constantly more than one eye supervising, watching over the course of studies. I told him, to my embarrassment, they even put in place detectives, who track each and every student, and monitor their behavior in the streets, in the home, and each and every place, and they report “violations” to their superiors – thus all the activities of students are documented in a book, a practice most students opposed.

“I admit without embarrassment,” I continued, “that I am not one of the studious ones because the Vilna students are not able under any circumstances to be diligent for six continuous hours in one spot. On my own I encourage myself this way by saying to myself – that I have already sat in study for much time and it seems to me that I haven't advanced in my studies, and God forbid (oi va voi) if I return home empty handed. In the end, each and every student, must try to acquire knowledge and wisdom on his own, according to his ability and his own idea. Obviously, there are those who are exceptional, but their numbers are insignificant. Most students exemplify [the saying] “[such is the way of a life of Torah]: you shall eat bread with salt and rationed water shall you drink, you shall lie[34] on the ground and in Torah shall you labor” [Pirkei Avot 6:4].

“And what about the subject of Zionism in the yeshiva?” he asked me. I told him that there are two streams among the youth. One is enthralled by socialism and the second Zionism. And how is it possible to avoid being Zionist, at the time the yeshiva was established, Rabbi Moshe Avigdor Amiel and Rabbi Yitzhak Yaakov Reines, the Rav of Lida, and more, trained hundreds of students and each had study partners.” I continued, “The hint is sufficient for the wise man.”[35]

In the meantime, 4 o'clock approached, the time for going to the synagogue to study a chapter of Mishnah and say afternoon and evening prayers.

[Page 215]

The Rav took leave of me and while departing his son Avramel said to him, “Father, why don't you bring him, [give him] 'a large portion of gemara' and examine his character.” He answered him, “there is no need, I already know the whole story” [indicating Mandelkern had earned his respect].

The Visit with Mr. Meir Feldman

In the meantime, our reputation preceded us in the town, and towards evening we were invited for dinner to one of the town's wealthy men, Mr. Meir Feldman.[36] In Mr. Meir Feldman, there was a mixture of Torah and wealth in one place, he was being cared for by sons, who also faced the problem of leaving parents and the town in order to be educated in the world at large.

The meeting in the home of Mr. Meir Feldman was different from that in the home of Rav Rabbi Mordechai Nute. While in the home of Rav, Rabbi Mordechai Nute, the meeting was conducted in a question and answer style, [whereas] in the home of Rabbi Meir Feldman this was an evening of disagreement among a group of friends about different subjects. Of course, in particular, the discussion [literally, the axle] turned on boys of the yeshiva, Hebrew culture, and Zionism, God help us. It was interesting that that each and every person saw Zionism as [inappropriately trying to] force the Messiah's arrival.[37]

R. Meir Feldman was a successful forester, among the rich in the area, and there was a custom among such traders, obviously also a convenient practice, to go from forest to forest and from place to place not with a rented wagon, but rather in a private vehicle, that took the form of a nice carriage and in the winter a nice winter sled with two noble horses. The person in charge of the vehicle was a gentile, and he would perform all the trips at the order of his superior. When the parents were in a good mood, they would permit their children, from time to time, to organize a fieldtrip for enjoyment. At the end of the discussions that evening Mr. Meir got up and said, “You see, children, when you have a strong will [to do something], you succeed.” And he concluded with the expression, “There is nothing that stands in the way of the will.” He ended with [the statement] to Asher Lemel, his son, that he would instruct the person in charge of the horses to pull together a fieldtrip for about an hour. As an aside, he asked us, “Where are you supposed to be tomorrow?” From his question, we realized that his son told him our goal in coming to Trovits. We told him that we had been referred to Mr. Chaykl Weitz, who lives in Boremel, by his cousin David Lerner, a brother of Artzi (who, by the way, is living now in Israel, a member of [the kibbutz] Meshek Kfar Giladi), to brief him on our goal, and since we already had left Mlynov, and the distance from Trovits to Boremel was short, we were headed the following day to Boromel. Because R Meir was feeling good about the whole evening, he instructed the coachman to take us the following day to Boremel. This was the very pinnacle of our success. It is interesting that during the evening fieldtrip not one of the girls from town participated, and it was left to the boys to interpret [its meaning].

In the Town of Boremel

The following day we were taken to Boremel, straight to the house of Mr. Chaykl Weitz.

[Page 216]

A Jew of medium height, he spoke Hebrew with us, a typical educated character (maskil) of the time. He was well dressed, had a well-kemp beard, such that I didn't know who copied [the beard] from whom – Mr. Chaykl Weiss from professor Chaim Weitzman[38] or the reverse…and when he heard about the purpose of our visit, he told us that he would invite us that evening for a meeting in his house with participation of the local Zionist committee, which he presided over as the chairman. When we left his house, we remarked jealously[39] to one another, “Boremel has Jews up in age who support the Zionist Committee, and Zionism is not considered to be a matter for young men and woman, who are idlers and so on.”

At 7 o'clock in the evening, the members of the committee, who were advanced in years, gathered together and after the chairman introduced us to them, he said to us, “Young men, say what you want to say.” We told them all the details about the mission sending a pioneer to the Land of Israel before the rest of the group and the essential challenge we faced finding funds for the journey. And due to the secrecy of the matter, we took upon ourselves to collect money for this goal exclusively from “birds of a feather” who live nearby. After very tangible questions, and not just “klutz questions,” he asked us, “How much do you want and how much has been given to you?” I, who apparently was one of the lead speakers, responded that during the building the Temple [in Jerusalem], the people brought gold, silver and copper, and they would choose on their own [what to give] from one of those three items. Then the chairman, M. Chaykl Weitz, said to the members of the committee: “Give them gold in the largest coin.” This was then 15 rubles of gold. And he provided a justification for his instruction, “I see in these young emissaries the golden youth [who will work] for the establishment of the Land of Israel.” The treasurer gave us 15 rubles and wished us complete success. The chairman, full of excitement over us, got up from his table and went towards one of the rooms, opened the door, and called, “Sara (his daughter), Come and meet the boys of Mlynov and enjoy the beautiful Hebrew which they speak and even with a Sephardic ascent!”[40]

After light conversation about current events and matters related to the Land of Israel, they asked us, where we were headed the next day. We told them, that we hadn't crystalized our plan yet, but we needed more money to cover the expense of the trip. Then they said to us, “there are many Jews like us, in other words Zionists, in Berestechko, which is close to Boremel, and we therefore recommend you head to the Zionist committee in Berestechko, and obviously we will recommend you.” The following day we traveled to Berestechko. Even though Berestechko was bigger and better organized in matters of Hebrew culture such as the Hebrew school, library and more – the Zionist committee was less organized. Nonetheless, they welcomed us and we didn't leave them empty-handed.

The following day, our friend Yirmeyahu returned to Trovits to teach Torah in the Fuksman home and I returned to Mlynov.

Among those who knew our secret [goal], who were also completely in on the secret matter [of the trip], was also our friend Chaim Yitzhak Kipergluz.[41]

[Page 217]

Since his education which he received from the Hasids of Stolin, it was hard for him to be in public with the four boys [mentioned at the start of the essay] who were enthralled by Zionism and he was considered a “Zionist prisoner” in other words: [he was] a “closeted Zionist.”

Upon my return from the trip, he was first to meet me and said to me, “Shmuel, don't worry, everything will be okay, since here, in our small town, a rumor[42] circulated and said that the yeshiva boys, Yermiyahu and Shmuel went to Trovits for a wedding, following in the footsteps of the beautiful daughters of Hirsch Goldseker who were invited to this wedding. That's good since the real secret is not known by most…”

I want to point out here the great faith that my parents placed in me. Despite my absence that entire week from the home they neither interrogated me nor investigated where I had gone. They believed that if I traveled, it certainly involved something of importance.

Preparations for Aliyah

In the first meeting of the four [friends after the trip], it was decided to continue with the efforts to raise the amount needed to reach the total expenditure required for the journey and to quickly tackle the implementation of our program's first stage, namely, to send Yaakov-Yosi to Odessa with the goal of his aliyah to the Land of Israel.

Not much time passed before the needed sum was fully in hand. Since we were afraid that something might happen on the train trip to Odessa, that was full of pickpockets and swindlers of all types, and that these pickpockets might also visit the pockets of Yaakov Yossi, and he would be at risk of arriving in Odessa empty-handed, and all our efforts would have been in vain – [for this reason] we sent 40 rubles to the committee in Odessa and to Yaakov Yossi we gave only six rubles, the expense money for the trip from Dubno to Odessa.

At this point, two important problems stood in our way: (A) since the trip from Mlynov to Dubno took place only via coachmen, such as Kalman Fishman[43] and others, and the trip left from the center of town, where the travelers were accompanied by their wives and others, the question was –how would we secretly integrate Yaakov Yosi among the other travelers and for what purpose is Yaakov Yosi suddenly going to Dubno? A question not simple at all. (B) how could we send Yaakov Yosi to Odessa, who was, as it were, our representative to the Odessa Zionist committee, with him in torn and worn-out clothing, since he was a son of poor parents who with great difficulty supported themselves?

The two problems were resolved with a better approach. We decided not to send Yaakov Yosi on the main road, in other words, with a coachman who traveled to Dubno, but rather, we, the whole group, would go together with him along the dirt road that goes to Dubno across from the Count's estate. There was a hill there covered in greenery where the youth used to gather as a pastime and for conversations with friends, especially on the Sabbaths; this hill was called “Mount Sinai.”[44] This hill stood in fact at the crossroads, that leads from Mlynov, [starting] from the village of Smordva, Berhy and others, to Dubno, and we knew that a wagon from one of the nearby farmers which were going to Dubno would occasionally happen by and would take him to Dubno, and in our town no one would be the wiser about the scheme.

[Page 218]

As to the second question [regarding his worn out clothes] – we decided that each one of us would pilfer from his home, without parental knowledge, one taking shoes, another pants, a jacket, hat, a nice shirt and more, and in that spot, on “Mount Sinai,” and in spite of the cold that had reached its [winter] peak, we would strip off his worn out clothing and dress him in a really nice outfit. And when we completed this effort, we suddenly saw before us a nice looking and healthy young man, with ruddy cheeks, his entire being announcing youth and vitality, and we almost didn't recognize him and we asked one another “Is this Yaakov Yosi?”…

|

|

| Boating on the Ikva River |

In order to coverup the traces of our last activity, we left Mlynov for Mount Sinai in the following manner: Three of us walked the road to Kruzhuk,[45] made a turn across the big bridge by the horses[46] and arrived at the designated place, while two would go straight from the town across the bridge over the Ikva and also reached the designated place. And after we changed his clothes, we took his torn clothes, put them on the banks of the Ikva that passed nearby – and if in the coming days a commotion would be made by his family, because Yaakov Yosi, their only son, had disappeared without a trace, we will participate in the search for him and we will find his clothes on the bank of the river, and this will be proof that he had drowned in the river…[47]

It was not a trivial problem how to stay in touch via letters with Yaakov Yosi in Odessa. The delivery of letters was done by the non-Jewish mailman, and in every house that he entered with a parcel of letters, they [the residents] would out of curiosity search through his bundle. There was a danger, therefore, that due to such searches, they might find out who sent the letter and who received it –and reveal the secret of Yaakov Yosi…

[Page 219]

Not one of us was willing for the correspondence from Odessa to Mlynov to come to his address, because each saw great danger in this. Yitzhak Lamdan was especially afraid – that he would disappoint his father who held him in very high esteem. Therefore, I took this danger upon myself. Since the mailman brought me the newspaper Ha-Tsfira”[48] daily, and frequently some brochures about forthcoming books, like Tushiah [“Sound Knowledge”][49] and Moriah[50] and others –he could also bring me the letters from Yaakov Yossi among the rest of the items.

In those days, a trip to Odessa lasted three days, and a letter from Odessa took three days, which meant that for [the first] news from Yaakov Yosi, it was necessary to wait at least six days.[51] Nevertheless, by the third day of his trip, my colleagues were already asking me “Have we still not gotten a letter from Yaakov Yossi?…”

On the seventh day, we received a letter from him – but, oh no! The letter was written entirely in Russian, and this was after all the efforts we invested in him in the roof attic of Mr. Mendel the writer (schreiber), to teach him, among other things the Hebrew language. Of course, I immediately ran as if bitten by a snake to Yitzhak Lamdan, to bring him the bad news of his betrayal of the Hebrew language, and the key thing was that it said nothing of substance about the trip to the Land of Israel, apart from his visit to Ussishkin.[52] Quickly, we sent him a letter indicating that the key item that interested us was when he would make aliyah to the Land of Israel, and with a light rebuke for his betrayal of the Hebrew language.

In the second letter that we received from him, he wrote that as far as his betrayal of the Hebrew language is concerned, who among us was as great as Ussishkin, and even in his house they spoke exclusively Russian…and with respect to his journey, it was too early to clarify the matter. His cousins, who lived in Odessa, did not agree with this trip and he still did not know how it would go down…and he continued with the following statement: “What are you all thinking, that Odessa is Mlynov? In Odessa, there are big beautiful houses and there are large establishments of commerce and many other nice things, that you have never seen. And there are boulevards and I sat there on one bench with a young woman…” After a short exchange of additional letters, we were convinced that our labor had been in vain and we gave up on Yaakov Yosi…

Immediately we notified the Odessa Committee, that the money we had sent them as funds for the aliyah of Yaakov Yosi, we were transferring to the credit of Keren Hakaymet of Israel [The Jewish National Fund] and with this we put the final nail in the coffin [of Yaakov Yosi's aliyah].

Our Yaakov Yosi remained in Odessa. He married, participated in WWI, was wounded and was left with a physical disability, and we said to ourselves that God had punished him for his betrayal of the Zionist idea. And if one asks, “what became of the commotion that Yaakov Yosi's family was supposed to make in Mlynov over his sudden disappearance?” – the answer is this: this schlemiel was smart enough to catch the wise in a trap… apparently, matters had all been agreed with his parents that he would exploit this opportunity to go forth into the world at large, and go to Odessa, without it costing him a penny. Perhaps he also thought that he would emerge from the affair with great wealth…

Translator's and editor's footnotes:

Return

by Boruch Meren[1], Baltimore

Translated from the Yiddish by Hannah B. Fischthal, PhD

Edited by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD

©

In 1921, when Reb (“Mr.”)[2] Moyshe Fishman (we called him Moyshe Toybe's [son][3]), an energetic Jew with a red, short beard in his middle years, disclosed the secret to one of his friends that he had decided to go (or as it was called in that time, “make aliya”) with his wife and children to Palestine, the news immediately spread throughout the shtetl.

At first, nobody wanted to believe it.

However, when it was discovered that Moyshe Toybe's already had the necessary papers, his passport with all permissions, and he had started already to sell out his household goods, then the shtetl started to believe it. This amazing event was talked about in the synagogue, in the market, even among the Christians from the village Slobada,[4] with whom Reb Moyshe had dealings. One expressed surprise to the other that “Moshka is going to Palestine,” to become a Jewish worker on the land.

Children in the cheders talked with enthusiasm and they were jealous of the Fishman family that was going to Palestine and would be treading on the holy ground about which they had just learned in the Bible. And they would be eating oranges, carob, and figs.

The adult Jews in the shtetl thought differently.

“You have to be crazy, heaven forbid,” they argued. “How does a Jew with a family, with a nice house, with a barn, a cow and horses, in addition to a small grocery store, a Jew with an income, a decent Jew with a seat facing the center of the eastern wall of the Trisk synagogue; how does he go and break himself away to go to a distant, empty land, where wild Arabs attack, kill and rob?”But Reb Moyshe was not from the people who allow themselves to be talked out of something.Friends argued with him: “Is it possible, Reb Moyshe, what are you doing? You are not allowed to break away.”

[Page 221]

“We are sick and tired of the Pollacks and all the Christian hooligans, the peasants. I cannot tolerate the businesses made in the air,” he said, “I feel pity for the poor Jewish storekeepers, who stand in the stores and keep looking for a customer. I can work on the field. I will become a moshavnik, (earth worker) and with God's help we will live and have what to eat. I will work harder, as long as I can live in our free country,” was his argument.Reb Moyshe Toybe's had a family consisting of five people: himself, his wife Khaye, two sons, and a daughter.[5] The younger son Berel had been taken by friends to America a year earlier,[6] and the oldest son Dovid, a young man of about 20, used to take care of the store. His head however was not into it. He hated the store and neglected it.

Going every day into the house of study I would walk by the little store, and I often went in to buy something. Dovid always used to sit with his head in a Hebrew book or journal. It was a sin if a customer interrupted him. The shtetl knew that he was a Zionist. His father could depend on his physical strength if hard work was needed.

* * *

I will never forget the goodbyes to our first family of pioneers. The night before they departed, their entire house was lit up all night long. All the Jews in the shtetl came to say goodbye. The house was packed with people. There was a big commotion. People kissed and cried.

All the baggage, in a separate room, was packed in large baskets and in sacks. I looked at a large basket and I thought how that very basket was going to Palestine. I wanted to get into the basket that minute and go along to the land that had so teased my young fantasy; I longed for the land of our fathers.[7] A group of students from the house of study, I among them, with our teacher Ayzenberg (he is now a friend in Kibbutz Ein Harod, near Balfouria, where our Moyshe Toybe's is a resident), stood and sang Hebrew songs, and at the end, the Hatikva.

[Page 222]

The crowd dispersed little by little, shrugging their shoulders, “What Moyshe Toybe's can think of!”

The next morning, not looking at the bitter cold and deep snow, curious people again gathered around his house. A few helped carry out the baggage and put it onto the wide, Christian sled, as the Christian driver was standing dressed in his thick fur coat with a bashlyk on his head.

Reb Moyshe with the children wore thick, warm, furs. They went onto the sled. The Christian whipped the horses, and the sled started to move from its place. The crowd called after: “Go in good health. Shalom! Shalom!” The sled headed out towards Dubne. In Dubne they embarked on the train, and from there they went more quickly.

The crowd dispersed. Only a small group of people remained standing in the small, paved yard and pondered the house and the barn, which now looked so empty and sad. I got closer to the group of people to hear what they were saying.

“And I tell you,” Yankele, Moyshe's [son][8] interrupted the silence, “that he will regret it forever. Look what a household a Jew sold out.”“Certainly,” the rest agreed while they tapped their feet as if dancing to warm up a little.

“The one thing we need to be jealous of Moyshe and his family—they are going to a warm country, and they will not freeze like we are,” Yankel, Hersh's [son][9] called out.

“That, yes,” they all admitted while touching their pockets to see if they had the keys to their stores. They left to open their stores.

* * *

A few years passed. The strength of the pessimists who promised Moyshe Toybe's would run away from Palestine and come back to Mlynov was not realized, not even considering the first difficult years that he and his family went through.

[Page 223]

The shtetl received regards and word that Moyshe had settled in Moshav Balfouria (in the Jezreel Valley) and was working very hard. Everyone added that Moyshe was a Palestinian Jew and would not come back to Mlynov.

In 1938, when I arrived in Palestine, I decided that I must see Reb Moyshe. When he had left Mlynov in 1921, everyone in the shtetl, sad he was departing but thinking he was insane to go so far away, had accompanied him to the sleigh.

In Balfouria it was not difficult to find him. I stood in the middle of the village and thought about the yards on both sides of the road. I saw small, white houses with red roofs and concrete barns behind each house, and white chickens in coops. I looked inside every yard and said to myself: I will search for the best-looking and richest yard, because Moyshe Fishman's yard was the richest in Mlynov. I went into the first yard that I liked, and there I saw Reb Moyshe dressed in working clothes. I recognized him immediately, although he was already almost white and had aged a great deal. He was standing next to his barn, and he divided groups of hay for the animals. It was lunch time.

“Shalom, Lord Fishman,” going closer to him.He lived then with his daughter and son-in-law, who helped in the field.[11]“Shalom and blessings. Who are you? What is your name?” he asked me, sticking the fork into a mountain of hay. He extended his lucky hand.

“I am Hersh Slobodar's grandson, Bentsye's son,[10]” I said to him.

“Really!?” He was happy. “Hersh Slobodar's grandson? If so, we belong together. Your grandfather and mine—well then, what's the difference? Come inside the house, grab something for your mouth and tell me about Mlynov, how they are there.”

[Page 224]

His wife was no longer alive. We sat and talked for a long time. He asked me about everyone. I reminded him about what the shtetl had thought about his going to Palestine. He smiled, but soon his face changed, and he became almost angry.

“Such scoundrels! Why are they still sitting in the stores? Why don't they run away? What are they waiting for, for Hitler to kill them, heaven forbid? Who knows, maybe it is already too late,” he added with a sigh.He looked at the clock and noted it was almost time to milk the cows.

“Come with me now to the yard, so I will show you my farm,” he said with pride.I went after him and thought to myself: How correct and wise he was in 1921, and how unwise were his critics. There is so much truth in Reb Moyshe's simple words. Maybe it is already too late?

“You see the white hens,” he pointed with his finger, “they lay more eggs than the Christian hens in Ukraine, and our cows cannot be compared to the Christian ones. Ours are fatter and better looking and give more milk. They are also smart and understand Hebrew.”He convinced me and said to one of his cows in Hebrew, “Pick up a foot,” and she actually did it.

“I am telling you, even a cow is smart in the land of Israel.”

* * *

In 1952 I met again Moyshe of the moshav of Balfouria in America. He flew over to visit for three months with his two sons, daughters-in-law, and grandchildren, who live in Baltimore. He was then about 78. He begged his children to show him American farms. He seriously studied them and added, “Very nice farms, but ours in Israel are nicer.”

Moyshe of Balfouria did not want to stay longer than three months in America. He was drawn to his home. Without him, he argued, his management will not be in order.

[Page 225]

Soon the hay will have to be gathered, and he must be there, he explained.

He took with him a gift for his synagogue in Balfouria—a Torah.

“Learning and devotion are needed in Israel,” he said with a smile.He said a heartfelt goodbye and asked us to come to Israel.

|

|

| A group of young people[12] |

Translator's and editor's footnotes:

by Yankev Holtzeker[1], Tel-Aviv

Translated from the Yiddish by Hannah B. Fischthal, PhD

Edited by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD.

©

Mlynov was extremely beautiful. The streets were clean. Leafy trees grew on both sides of the road. In May, when the flowers started to blossom, we actually became drunk from the aroma. The shtetl looked like a forest in bloom. We also must remember that in Mlynov all Jews used to plant a couple of trees near their houses or in their gardens.

The River Ikva flowed through Mlynov, adding to its beauty. Young and old used to come and bathe in the river or warm themselves in the sun after a hard day of work. There were various sports games, which the young people enjoyed. The bridge which crossed the river and led to the count's palace also added to the shtetl's charm.

Culturally, Mlynov was on a high level. In addition to the public Polish school, there were several cheders as well as a Tarbut School,[2] where every youth in Mlynov could learn. As already mentioned, young people had the possibilities of benefitting from various sports clubs and competitions with groups from other surrounding shtetls.

In Mlynov there were several Zionist movements, like The Young Guard (Hashomer Hatzair), Betar, and others. We used to get together to have a good time, read books, and hear various Zionist speeches. There were also excursions. On Lag B'omer, for example, we used to go into the nearby forests and have fun a whole day, returning home at night. In the winter young people would take sleds down the mountains in the moonlight. The political parties used to organize various events and plays.

Mlynov owned two synagogues: the Stoliner Synagogue and the Olyker Synagogue, as well as a House of Study, where all people would come and learn Torah until late in the night. Every Shabbes, the synagogues would be full of enthusiastic Jews.

[Page 227]

During holidays the synagogues were even more crowded. The study house is especially engraved in my memory. It was the place where I used to pray with my father, may he rest in peace. With his high and sweet voice, he led the congregation. I remember also how he used to sit and learn until late at night with other Jews of the Mishnah[3] Society.

* * *

And Simchas-Torah, I remember that we used to organize Simchas Torah night at Nokhum Teitelman's,[4] may he be celebrated with a long life. The entire party was there. He was also in the Mishnah Society. We used to dance out of the synagogue with the holy books and with music, locked by our arms into a long chain. We danced until we reached Nokhum's house. There we made a real feast. Afterwards, with the same joy, we would go again to the synagogue.

* * *

|

|

| A group of young people Pesach Mendelkern, Dovid Holtzeker, Rayz, P. Kleper, Y. Lieberman, Sh. Shechman[5] |

[Page 228]

The Jews of Mlynov were virtuous and ethical. Their high moral standards resulted in being kind to guests, and in helping one another in every need. They led modest lives. The Jew in our shtetl was a worker who realized he must “Eat bread by the sweat of your brow (Genesis 3.19).” I take this opportunity to remember my Uncle Avram Gelman z”l, with his fine qualities. He sacrificed himself for everyone with whatever he could, whenever someone was in need. My Rebbe Meren,[6] too, used to exert his greatest efforts onto all the children so that they could learn.

Moreover, I remember all the honest Jews, like Yankev Holtzheker,[7] whose house was open for every needy Jew, even though he himself had a large family. All the Holtzhekers were like that. In my father's family, each person separately used to sacrifice for all. And I note my mother Toyva, Reuven Ostriyever's daughter, a pious woman with a good heart.

And in general, all the Jews, the artisans, businessmen, traders, and a large percent of farmers, were good. Everyone made his living with honor and honesty.

* * *

I will tell a little about Mlynov after my return from the Red Army, after the Holocaust, in 1945. Broken physically and spiritually, I still had the great privilege of taking revenge for our dearest brothers and sisters, fathers, and mothers.

The shtetl looked like a catastrophic graveyard. Every little footpath was saturated with Jewish tears and blood. I got frightened as soon as I approached my shtetl. Everything was blocked and ruined. All the streets were a mountain of stones. The only Jewish houses remaining were occupied by Christians. Not a trace remained of the Study House and the other synagogues. Everything had been destroyed. Wild grass grew on the streets.

I went only to my brother's grave,[8] located on Kruzshak, between Mlynov and Mervits. I wept heartily because of the dark fate that had befallen us.

Translator's and editor's footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Mlyniv, Ukraine

Mlyniv, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 3 May 2022 by LA