|

{Popivitsi is 3 miles NNE of Kopaigorod}

|

|

The provincial government committee on public education approved the opening of a school with two grades and two teachers in Kopaigorod at its annual meeting on September 25, 1910. The Kopaigorod secondary school was founded in 1911 when the Russian Ministry of Education also established a three-grade progymnasium, a preparatory school attended before secondary school. Students studied there for three years after finishing a parish school. Mykhailo Terletskyi was the first principal of the school. Before 1911 there was a parish school in Kopaigorod. A new addition in 1893 included a teacher's apartment, a library, and a room for icons. The teacher in the school in 1893 was Julian Zagumenyi; he had studied at the Ostroh Teacher's Seminary. At that time in the literacy school in the village of Romanky {or Ukrainske, on the SE outskirts of Kopaigorod}, the teacher was Foma Tanasiuk, who graduated from Kopaigorod parish school. The salary of both teachers was 100 krb or karbovantri in Ukrainian currency. The parents of each student also contributed one ruble each for heating.

The church also maintained a school in the village of Romanky, where a new building was built in 1899. These were exemplary schools at that time. Both schools received 30-50 krb annually from the state for maintenance. The law of God was taught here by the priest V. Shostatsky, the teacher was D. Petrovsky. The weekly newspaper Orthodox Podolia wrote in September 1912, that the priest V. Shostatsky was in charge of the Orthodox church school in Kopaigorod, and P. Mudryk served as a teacher. The history of the Mudryk family from Shypynky was well-known. The parents had six children. The beginning of the dynasty of teachers was laid by Pavlo Mudryk, who, at the beginning of the 20th century, opened in Shypynky {just a few miles NW from Kopaigorod} a school in his parents' house. Then he worked as a teacher at the parish school in Kopaigorod. Later, his brother Petro, also a teacher, joined him. Paul chose the path of a priest and left for Kalmykia. Peter was the director of the school in Kopaigorod before the war where his wife Vera also worked. Peter's sister Maria was a teacher at the Kopaigorod National School. Their family has a document – a certificate No. 149 of the Mogilev-Podilskyi administration dated July 4, 1917, about the completion of Maria Mudryk's Ukrainian folk pedagogy courses. For some time, she worked in the city of Bar. Peter's daughters, Galina and Tatiana, were also teachers. Tatiana worked in various schools and in Kopaigorod too. (Based on the materials of the post by V. Zelenyuk. Deep roots of the Mudryk family, Vinnychchyna newspaper, April 17, 2009).

Mykola Ivanovych Pyrohov (1810-1881), famous surgeon, scientist and trustee of the Kyiv educational district, once visited these schools and I believe that he would have approved of the Jewish schools as well. The attitudes of Pyrohov and the government of tsarist Russia towards the Jews were completely opposite. Mykola Ivanovych admired the desire of Jews to educate their children. He wrote in Odessa Vestnik, that:

Jews start teaching children from the age of 4. A Jew considers it his most sacred duty to teach his son, who has barely learned to babble, to read. This he does, out of a deep conviction that the letter is the only means of learning the Law. He has no disputes, no magazine polemics about whether his people need literacy. In his mind, whoever rejects the need for literacy rejects the Law.

The Podillia Diocesan Information No. 6 for 1894 stated that, “Education in this school was good; the students showed excellent results in the exams.” At the start of the 1896-1897 academic year, the Podillia Diocesan School Council proposed opening a two-class boys' school in the town. In 1903, the Zemstvo opened a two-class folk school. In 1917, this Zemstvo primary school had three classes. The duration of education was for four years and there were three teachers in the school.

Jewish children were instructed in Yiddish and Hebrew in the cheder. As children began attending cheder at the age of four, it served as a kindergarten and freed the woman for work. Corporal punishment was also practiced in cheder. The education achieved depended on the teacher's ability to teach, and the students' ability to learn in that environment. Students appreciated it when their teachers discussed various topics that did not relate to the curriculum. The students preferred that to shouting, learning, and a ruler. After time, a corrected cheder appeared, where there was a special room for classes, a blackboard and chalk, a curriculum, lessons, and breaks between them, and separate classes on Hebrew and Tanakh. There were even cheder schools for girls. The Ministry of Public Education issued an order dated November 13, 1844 on the opening of Jewish schools in the Podillia Governorate. A first-class Jewish school opened in Kopaigorod in 1845 which corresponded to the parish school. Education was monitored by the Ministry of Public Education under the Podillia Provincial Jewish School Commission. In 1915, the cheder was run by Ovshiy Farber. Motl Ostrovsky, a resident of Kopaigorod related a story about the town cheder. In 1906–1908, Yankel, was the melamed who taught reading and basic religious knowledge to children from the age of four. There were other melameds there as well. Shiya-Nute, Zeide, and Freuke taught the older children. Motl studied with all these teachers. And when he was thirteen years old, his father sent him to study with Rebbe Yankel-Pinchas, and then with Melamed Yosyp-Meyer, who was a progressive teacher who did not beat the children, and who taught them to write in Hebrew. The last melamed with whom Motl studied was the teacher, Avrum Arzon. From this we know that there were several cheders in the town.

There was also a Talmud-Torah in the town. This was a school for poor children whose parents could not pay the melamed. The Talmud Torah was usually under the control of local authorities; in addition to religious subjects, Russian language and general subjects were taught there. It was considered shameful to send one's son to the Talmud-Torah.

Not all of the Jews in the town were literate. After all, only boys were supposed to be taught, and literacy in Yiddish or Hebrew did not provide much in the way of general education. Access for Jews to high schools and universities became possible in 1846, thanks to the introduction of a law on general military conscription which made the term of service dependent on the degree of secular education. The new military statute established the term of service at 6 years with a gymnasium certificate, and 1.5 years, with higher education. Jewish boys then flooded Ukrainian schools, to which the authorities responded by introducing the infamous percentage norm in 1886 {which was a legislative restriction on the admission of Jews to higher and secondary education}. But nothing could stop the desire of young people to get education. A good education also meant the ability to speak Russian without a town accent, which was the goal of Poalei Tzion, The Jewish Social Democratic Labor Party. Ber Borokhov mentioned that his family stopped speaking Yiddish so that when the children went to gymnasium their pronunciation would not have a Jewish accent.

This is why some parents sent their children to Ukrainian schools. For example, in 1925, a third of Jewish children of school age in Kopaigorod studied in a Ukrainian school. This was the case in schools across Ukraine. As the parents still wanted their children to learn Hebrew as well, which was then forbidden, children from many towns wrote letters to the All-Ukrainian Central Committee to request permission to study Hebrew. By the end of 1925, there were 342 schools in Ukraine, where 1,438 teachers taught and more than 56,000 children. On average, only 26% of the Jewish children studied in their native Yiddish. The existing network of national school institutions, the creation of which was initiated by the Soviet authorities, did not meet the needs of the towns' populations. This is evidenced, for example, by the data on the state of education in Vinnytsia District. There were 5,830 Jewish children of school age, but only 31.6% were enrolled in school. School premises were often very small and not well adapted to the educational process. Due to this unattractive reality, Soviet Jewish schools gradually lost their popularity.

|

|

{Popivitsi is 3 miles NNE of Kopaigorod} |

|

|

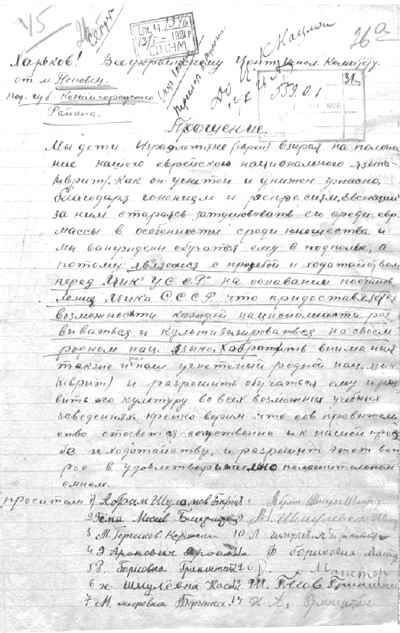

REQUEST We Jewish children are concerned about the condition of Hebrew, our Jewish national language. It is oppressed and humiliated due to persecutions and repressions. We are not allowed to learn and speak it legally, especially young people. That's why we have to learn it secretly. So we appeal to the Central Committee of the Ukrainian SSR to allow for the possibility of our national and cultural development. We want to study in our native language in all educational institutions. We do believe that the Soviet government will take our request into consideration and satisfy it.

Abram Shulamov Baron |

Responsibility for the parish school was transferred to the church, and in 1893 a new building was built to accommodate the school. As of 1917 there was one teacher for this three-year school. This building was still used for a three year secondary school in the 1950's. When we moved to live in Kopaigorod, my sister and I studied in this very building.

Construction of three capital school buildings in the northern part of Kopaigorod was carried out by the Zemstvo, or local government. Three classrooms, a teacher's room, an office and the principal's office were located in one building. Two houses were built for the teachers' families. I still studied in these rooms, as they were preserved and there were not enough classrooms. In 1918, a part of the school was occupied by the invading Austrian troops. The director of the school appealed to the leadership of the Austrian troops with a request to vacate the premises so that classes could be held there.

The main building of the school was built in 1921. At the same time, a six-year school for rural youth was opened, which was later reorganized into a seven-year school.

Two Likbez schools, a program carried out to increase literacy among adults in the country, were instituted in 1923. The first one, in which all subjects were taught in Ukrainian, was managed part-time by the teacher Luka Ivanovych Yakymlyuk. Hersh Nusymovyc Kritzman, the director of the second school, where instruction was in Hebrew and Yiddish, was also the director of the Jewish labor school. Each two year class finished their schooling in the Likbez schools in the 1920's, however there still were Jews who could not write in Ukrainian or Russian.

|

|

|

|

I remember how we came to know Dina in the late 1950's. She lived near us and she received letters from her daughter who lived far away in another city. My mother read the letters to Dina and wrote letters in return to the daughter. Dina came from a very poor Jewish family and had not studied in school.

At the same time, a six-year school for rural youth was opened which was later reorganized into a seven-year school. There had been a Ukrainian gymnasium in Kopaigorod since 1917. The schedule of classes and teachers were: Andriy Volodymyrovych Fedosiev - director of the gymnasium and mathematics teacher for grades 1, 2 and 3; Archpriest Volodymyr Shostatsky who taught religion for all grades as well as in a one-class Zemstvo school; Kateryna Yukhimivna Chekan taught Russian language and literature and history in all grades; Artem Petrovych Danylevich taught Ukrainian language and literature, geography and natural science, and was secretary of the pedagogical council; Solomon Yukhimovych Frisht taught Hebrew for Jewish children studying in the gymnasium, as well as French in grades 2 and 3, and German in first, second and third grades. Nataliya Mykhailivna Hanska worked in the preparatory group where she taught Ukrainian, Russian languages and literature, as well as mathematics; Lidia Oleksandrivna from Terlets taught calligraphy and drawing in elementary grades and in the preparatory group. In addition, she taught in a one-class Zemstvo school. Andriy Fedorovych Rishetnikov taught gymnastics; Nifont Mogilevich was the vocal teacher. A meeting of the board of curators of the gymnasium took place on November 2, 1918, during which the Temporary Table of Lecture Schedules in Ukrainian Gymnasiums under No. 6262, was discussed. After the discussion, the committee decided to ask the Department of Secondary Schools under the Ministry of Education and Culture to approve their lecture schedule that had been compiled earlier by the board of curators, and to ask them to send them new programs of scientific subjects according to the new schedule of lectures. (TsDAVO of Ukraine F. 2201, op. 3. File 35)

In November 1918, the director of the Kopaigorod Ukrainian Public Gymnasium, A.V. Fedosiyev, sent a letter to the secondary school department of the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of Ukraine, with a request to approve the schedule of lectures, and attached notes from the meeting of the school's board of trustees. The gymnasium had three classes and one preparatory class.

In 1935, E. Basenko was appointed to the position of school director of the seven year old school. In recognition of its achievements in education and the upbringing of the younger generation, the People's Commissariat of Education of the Ukrainian SSR awarded the school with the Red Flag, which is still a relic of the school, a set of wind instruments and a cash prize in the amount of 2,000 kr. Among the five best schools of Ukraine, it was named after the Russian classic poet, Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin.

|

|

97. About giving the name of A.S. Pushkin to Vinnytsia secondary school # 18, Kopaigorod secondary school and Tulchyn secondary school.

Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the UkSSR resolves to:

Kyiv 20 September 1937

The head of the Central Executive Committee of UkSSR G. Petrovsky |

In 1937, the school graduated the first 10th grade class and became a secondary school.

The red flag somehow disappeared from the school during the war. The police searched for it but could not find it. It was only before the retreat that the occupiers found that flag hidden in a wall niche. It was discovered by a Soviet sniper, O. Dorosenko, while in Hungarian territory in 1944 near the city of Debrecen. As per the instructions of the commander of the unit, Colonel Bidakh, the relic flag was returned to the school in 1945. In 1965, twenty years later, after the return of the flag, O. Doroshenko was invited to school and told us about the war and the history of the flag.

|

|

In the pre-war period, many talented teachers worked in Ukrainian schools, including I.A. Nikolaychuk, V.K. Mudryk, V.I. Stakhov and others. I.N. Poberezhny, who taught history 1935-1940, was a colonel in the war, and after the war he worked as the dean of, and professor in, the historical and philological faculty of the Ivano-Frankivsk Pedagogical Institute.

During the war the Romanian occupation authorities did not stop the educational process. Education was conducted in the Ukrainian language, and even tenth graders were issued certificates of secondary education. In terms of the organization of the schools, the Soviet educational programs were preserved by the occupation authorities, but everything related to Marxist-Leninist ideology was completely removed. The principles of natural science were interpreted somewhat differently, the number of hours given to studying the history of Ukraine decreased. World history and the history of Romania were taught. A specially published manual, Brief History and Origin of the Romanian People was supposed to confirm the historical rights of the occupiers to the land of Transnistria. Compulsory study of the Romanian and German languages, as well as the Ukrainian language were introduced into the school curriculum. The ability to read, write and count was mandatory for all children and teenagers.

During the war, the teacher J. Kramer conducted classes illegally for Jewish children in the ghetto. He gathered children of different ages and worked with them for several hours a day in the basement of one of the buildings. After the liberation of Kopaigorod from the occupiers, the teachers who taught during the fascist occupation were dismissed from their jobs and prosecuted. Secondary school principals after the war were: Sydorenko, V.K. Pirus, F.G. Svyatenko, A.S. Terezman, A.S. Kukhyna, M.F. Bondar (1955–1963), and I.A. Voytsekhovskyi (1963–1985). The director of the school after 1985 was V.V. Naumenko. This young but experienced history teacher preserved the traditions of the school. In 1977, a typical three-story school building to accommodate about 1,200 students was constructed through the initiative of the principal, I. Voytsekhovskyi, and sponsored by A. Lekko, a Hero of Socialist Labor and director of the state farm, Bolshowyk in the Shpinka village.

|

|

Copyright © 2010 KZ “Kopaygorod Lyceum”. Source URL: https://kpg.baredu.vn.ua |

M. Pirogov said: “Each school is proud not of the number, but of the glory of its students.” Many of its graduates fondly remembered attending the Kopaigorod school, and the school was proud of the achievements of its graduates. Among the graduates of the school were: V.V. Osypchuk - Hero of Socialist Labor, honored agronomist of the Ukrainian SSR; O.N. Bidny - director of Kyiv and Kanevskaya electric station; V.T. Tekhmister - an artist, an honored worker of culture; M.P. Zakharchuk - an honored geologist; PS Mamchur - master of sports of the USSR; Zh.B. Savytska-Svytyuk - a member of the National Union of Writers of Ukraine; E. Kolesnik – Doctor of Technical Sciences; G. Ya. Kostyuk - professor of Vinnitsa Medical University; A.M. Podolinny - professor of Vinnytsia Pedagogical University, member of the National Union of Writers of Ukraine, publicist, local historian; SI. Kruchok - a doctor of agricultural sciences. Also there are the candidates of Sciences - V.A. Krupelnytskyi, L.P. Bohdanova, V. Dyakov, V.M. Skudny, V.S. Lyubun, A.S. Lyubun, V. Borsolyuk, N.I. Gulevich-Povar, I.L. Konivichenko, V.V. Pushkar. Many more talented engineers, experienced doctors, teachers and other specialists were first educated at the Kopaigorod School.

|

|

Many benefactors-graduates of different years donated money to the Kopaigorod secondary school in 2021 to purchase equipment for the school. Among the graduates who live abroad are: Eva Bogomolna, Oleksandr Borukhovich, Semen Bunyak, Bella Vinokur, Yevgeny Vinokur, Sofa Vinokur, Yakiv Gelin, Herman Alik, Semen Herman, Faina Herman, Fishka Herman, Hetsilevich Zinaida, Raisa Zhivilko, Milman Zinovy. Mykhailo Moreinis, Yukhym Okopnik, Bronislava Pogorelova, Mila Pudel, Semen Segal, Faina Feldman, Zakhar Fishilevych, Sonja Fishilevych, Sonja Fishilevych-Efroimska. The organizer of the financial aid to the school was a former graduate, and later a teacher of this institution, Lyubov Adamivn Legka.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kopaihorod, Ukraine

Kopaihorod, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 23 July 2025 by LA