|

|

|

The well-known Ukrainian public figure, Roman Koval, wrote in 1993 that Kopaigorod was a Jewish settlement. Jewish history in Kopaigorod seems to have begun in the mid 17th century but there is no official date of record. The fact that four fairs a year were approved for Kopaigorod during this period contributed to the settlement of Jews here. The fairs took place over one to two weeks. We learn from the Archive of South-Western Russia, Volume II, 1890, that Poland conducted a census of Jews in Letychiv district, which included Kopaigorod. It was noted that the Jewish kagal (a form of administration in Jewish autonomous government in Eastern European countries) of Kopaigorod included in its territory, 171 people and 62 houses. In addition, Jews lived in the surrounding villages that belonged to the Kopaigorod kagal: in Romanka - 6 people, Volodiyivtsi - 7 people, Shipinka - 6 people, Kosharyntsi - 14 people, Kurylivtsi - 5 people. The total number of Jews in the Kopaigorod kagal was 209.

The first document that reported the official number of Jewish residents of the town was the 1847 census. According to this census, the Kopaigorod Jewish Community consisted of 617 people, including Jews from nearby villages. The counts in later years were: 1897 – 1,720 (58.3%), 1923 – 1,021, 1939 – 1,075 (37.4%) Jews. The vital records indicate that in 1845, 19 girls and 12 boys were born, 11 couples were married, 11 men and 5 women died. In 1846, 16 girls and 15 boys were born, 28 men died, and 18 couples were married. In 1890, 42 Jewish children were born, including 23 boys and 19 girls. In 1899, 61 children were born, 34 were boys and 27 girls. In 1916, 38 children were born, counting 14 boys and 24 girls. In 1918, 34 children were born of which 17 were boys and 17 were girls.

I. Leopovets was the elder of the community in the 1930's. One of his duties was to keep vital records in books, called a pinchas. Itzko Yankel was the rabbi during that time. In the 1840's the rabbi in the town was Shulym Spivak. In addition, Rabbi N. Naftulishen and the rabbi-mohel Elya Spektor worked in the synagogue. Noble Jews in the town took part in the circumcision ceremony: Benzion Belin, Leib Spivak, Srul Katz, Benjamin Katz, Froim Rabin, Abram Kramer, Mordko Lieberman. In the period of 1890–1918, the rabbis were: Sh. Sheinis, I. Kinyavsky, K. Yasinson; mohel-Pinchas Zeldin, Moisha Zeldin, Elya Hershl Spivak, Michel Moreini, Itzko Meitser, Zus Spivak. N. Goifman, Elya Hershl Spivak, S. Grubman, H. Liskus, M. Weinberg, I. Kraiz, F. Waisman, O. Farber, and G. Glicker. L. Nishchii worked at the synagogue and did various public works. (From Jewish vital books for Kopaigorod).

Circumcision, or brit milah, was performed by a mohel on the eighth day of a baby boy's life. A mohel did not usually have a medical education, but he performed this operation better than many surgeons. The practice of brit milah was actually banned in the USSR, but it was conducted illegally and in secret. At that time, there was no mohel in Kopaigorod, and so the mohel, Shimon Kleiman was invited from Shargorod to perform a brit milah. Shimon Kleiman was known to be a mohel, a rabbi and a shochet.

There were fifty-two Jewish families who paid taxes recorded in the census, or Revizskaya Skazka (revision list). At that time, Jews did not have surnames, so the parents' names were included in a written reference. Starting in 1795, the censuses, or Revizskiye Skazki, delineate the many varied craftsmen of Kopaigorod. There were shoemakers, tailors, blacksmiths, hatters, potters, furriers, coopers, and others. According to the 1795 Revizskaya Skazka, the following Ukrainians worked under the great-grandfather Y. Sulyatsky: Shoemakers - son of Anton, Shportiy, son of Ivan, Galamaychuk, Vozny, Harmatovych, Rempovych, son of Danilov, Belyy, son of Ivan, Galamaichuk, Shvets. Furriers - Moskalchuk, Ivan's son, Prokopov, Panchuk, Bylynsky, Kurylivska, Chernavsky. Potter - Trushevskyi. Carpet Maker - Vasiliev's son. Barrel Maker- Andrei's son. Miller - Ivan's son, Timofeev's son. Smith - Grigoryovych. Bread Maker - Demyanchuk, Oliinyk, Moroz, Fedorov's son, Voytilin, Serhiyko, Vozniy, Serhiyko, Skorobogach, Voytyuk, Kohanin, Vozniuk, Sydorenko, Stary, Makodzei, Pavlov's son, Furman, Gavrilov son, Poberezhny, Pichkur, Namanyuk, Smetana, Babchuk, Antonova's daughter (widow), Folyushnik, Dubina, Babyn, Marusyn, Poberezhny, Kilimnyk, Kurylivska.

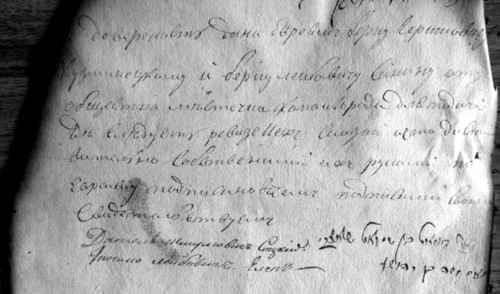

In 1811, Revizskaya Skazka was held in Kopaigorod. The Jewish community commissioned Berk Hershkovich Kozynetsky and Berk Leibovich Sanin to take the required census among the Jews.

|

|

According to the Revizskaya Skazka in 1811, there were twelve tradesmen recorded, including three shoemakers, six hatters, one boilermaker, one coppersmith, one tailor, and one-hundred- seventy-eight Burghers. This number included Jews living in nearby villages and part of the Kopaigorod Jewish community. In 1806, ten people were registered as tradesmen, and ninety-six as Burghers, so over a few years there was an increase in the number of people recorded in the revision lists. The revision list of 1844 indicated that the Kopaigorod Jewish community paid taxes on income from houses, warehouses and other premises that were rented out; from the profit of their shops; from the monetary capital left by the deceased; from renting wine bars, pubs and other drinking establishments and for wearing Jewish clothes. In 1844, the amount of tax that the community paid was 10,090.45 kr. (According to the materials of DAKhO. f.280, inv. 166, ref 1844.

According to the results of Revizskiye Skazki in 1851, there were 311 Jews in Kopaigorod, including merchants, burghers, and tradesmen, consisting of 311 men, and 366 women. The census was carried out on a special quality of paper intended for documents, called stamp paper. Naftula Naftulishen, Ios Yarmolinetsky, Leiser Abramovich, and Anchen Abramovich took part in the registration. The lists were signed and sealed by state rabbi Shmuel Spivak.

|

|

|

|

|

At the bottom it is written that this letter was signed by Berko Hershkovich Kozynetskyi and Berko Leibovich Sanin.

|

|

|

Naftula Naftulishyn Yos Yarmolinsky Leyzor Abramovich Yankel Abramovich |

|

|

The year 5570 (1809–1810) is written in the center. |

|

|

And such a print of the seal was in the community of Yaltushkov, where it is written: “sobrania Yeshurun of the holy community of Yaltushkov.” Yeshurun probably means an honorable name for the people of Israel.

|

|

Monuments of Jewish art ( “Decorative Art of the USSR”, 1966, No. 9).

The chief rabbi of Kopaigorod in 1854 was Shuly Spivak.

Members of the beit midrash council were: Naftula Naftulishen, Alter Haim Hershkovich, Abram Srulovich, Shulym Katsev, Leib Abramovich, Abram Spektor, Srul Kats, Volko Kalinovsky, Yudko Oksman, Srul-Leib Spivak, Elya-Gersh Berkovich, Shoriya Yarmolinetskyi, Nahman Vyrsta. As of October 1854, Abram Spector was the director of the Cheder in Kopaigorod. Students in the Cheder were: Abrashka Davydovych Brikil (age 9), Tsal Davydovych Brikil (age 7), Aron Hershkovich Spector (age 7), Shaya Leizorovych Spector (age 4), Srul Naftulishen (age 6), Elya Kreimer (age 5), Mortko Brikil (age 6), Duvid Brikil (age 7), Faybysh Naftulishen (age 4), and Srul Gelman (age 4). Minyan Beit Midrash in Kopaigorod in October 1854 included: Naftula Naftulishen, Yankel Gelman, Elya Spektor, Yankel Brikil, Leiser Spector, Kramer, Duvyd Naftulishen, David Brikil, Motl Chivler, and Leib Abrashka Leidvan. The Gabbai (head of the synagogue) was Leib Srulyovych Spector. The minyan in the synagogue included: Aizyk Kishka, Moisha Schneider, Srul Fotlyshen, Zus Fotlyshen, Abram Kishvar, Kiva Kivyshen, Shulym Katsef, Bynym Katsef, and Schneider.

In 1855 the beit midrash council included: Naftula Leibovich Naftulishen, Ios Yarmolvinskyi, Moisha Yarmolvinskyi, Srul Spivak, Yudko Oksman, Volko Kolankovskyi, Yankel Brikil, Min Brikil, Duvid Brikil, Shariya Yarmolvinskyi, Elya Hershl Spektor, Haim Hersh Iosevych, Haim Hersh Kosyka, Ovshia Kremer, Shulym Spivak, Abram Spector, Mortko Braytshin, and Shulym Katsef. (DakhmO, f. 3, op. 1. File 321).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Revizskaya Skazka of 1858, it is indicated that among the non-religious Jewish community in Kopaigorod there were 19 men and 17 women who were merchants, and among the burghers of various ranks, there were 223 men and 265 women.

In 1816, the Podil Governor O. Bakhmetyev, who owned the village of Stanislavchyk, invited artisans and merchants from Kopaigorod to live and work in this town.

According to the data of the population census conducted before the partition of Poland in 1760, there were Jewish craftsmen in more than twenty professions in Kopaigorod in the Podillia Voivodeship. Among them were barbers, healers, bookbinders, parchment makers, leather workers, midwives, butchers, tailors, goldsmiths, shoemakers, painters, carpenters, stove makers, locksmiths, coppersmiths, tinsmiths, blacksmiths, coopers and carters. There were craftsmen who made signed ritual items, sacred work. Arkhangelskyi was one of such masters in the town. According to the data of the Kyiv Governor General (Police Unit No. 2, Part 2) in Kopaigorod in 1850, there were 41 local craftsmen and 10 from other places, all assigned to craft shops.

Ukrainian art critic and ethnographer, Pavel Zholtovsky (1904-1986) published an article in the magazine, Decorative Art in the USSR, in the 1960's, in which he wrote about the Jewish culture that was lost during the years of Nazism. In his article, written with deep understanding and warmth, Zholtovsky wrote about the variety of Jewish sacred work that he personally remembered as living and attractive phenomena, some of which are described in his words as follows:

Masters from Jewish shtetls painted the premises of synagogues and were engaged in artistic casting and chasing, weaving, embroidering synagogue curtains and ritual covers, and making paper cutouts. Murals of wooden synagogues are distinguished by monumental forms.Among Jewish artistic crafts, copper casting stands out, mainly of various lighting devices, from table candlesticks to huge two and three meter high synagogue menorahs. In the 18th century, that exceptional and decorative type of menorah was formed, which existed for almost the entire next century. One of the best examples of such a lamp is the menorah from the town of Bar in Podillia, a typical decorative product of the late Baroque. Solemn baroque motifs are combined here with the image of birds and animals.

No less original was the jewelry art of Jewish craftsmen, who widely used chasing, filigree, and engraving. Their products are thin, elegant, and most importantly harmonious in form and ornament. Let's stop at least on the hoodes - one of the decorations of the festive Saturday table. The purpose of the real thing is to store cotton wool soaked in incense. Hoodes usually have the form of an intricate filigree turret with weather vanes. But often hoodes are made in the form of bizarre fish, rams, and trees.

Fine pointers for reading the Torah, filigree and silver bindings of books of fine openwork and engraved work are noted for great artistic taste.

Remarkable skill was shown by coppersmiths, or bliakhari, in the animalistic genre. Their birds, snakes, deer of generalized and expressive forms adorn vessels for ritual washing of hands. The height of the embossed relief, its tension are perfectly linked with the shape of the dishes. Woodcarving is also a common type of artistic craft. Lush Aron Kodesh, the holy ark in which the Torah scrolls were kept, were made with decorative carvings, similar in character to the carved decorations of Ukrainian iconostases.

Jealous attitude to sacred texts, the desire to preserve it in its original manuscript integrity - all this contributed to the development of sophisticated calligraphic skills. The work of scribes often strikes with genuine artistry.

Among the literate part of the inhabitants of the ghetto, a very peculiar kind of art developed, the cutting out of tables, panels, rosettes from paper and parchment. These were complex compositions, including pictorial symbols, figures of birds and animals, menorahs, tablets. Motives of synagogue wall paintings, artistic casting and frontispiece engravings of Jewish publications, and decorative wood carving are combined here in abundance. This included both the strict tectonics of the Renaissance and the peculiar baroque elements that were stubbornly preserved in Jewish art even in the last century. With all this, the feeling of the material, it would seem, the most unpretentious - a sheet of paper dominates here.

Paper cuttings had both cult and everyday significance. Among them are Mizrahi wall tables, shvuoslekh rosette-tablets associated with the everyday celebration of Shavuout, or the Pentecost. They have almost no lyrics, and the composition is simpler. They were usually made by students attending Jewish cheder schools. Rituality, permeating the entire life of Jewish shtetls, brought to life a number of everyday things related to everyday rituals…(P. Zholtovsky, Monuments of Jewish Mystery, Decorative Mystery of the SRSR, 1966, No. 9).

List of believers of the Kopaigorod prayer house beit-midrash in 1878, ninth from the top from the left at the beginning of the list is my great-grandfather Nuta Hershkovich Iosevych.

|

|

Translation:

Liberman

????? Yopsiovich Royzentul

Leybysh Yosiovich Shister |

Beginning in 1886 the rabbi of Kopaigorod was Mihel Mireini. At the end of the 19th to the early 20th century, the rabbi was Sh. Shifman, who later went to Snitkiv and worked as a rabbi there. At this time, there were three synagogues in the shtetl, each belonging to a different Hasidic sect. According to the 1897 census, 1720 Jews lived in the town out of the total population of 2950 people (58.3%). In 1906, 20,155 people lived in the Kopaigorod Volost, of which 2,618 were Jews, which was 12.99%. One resident of Kopaigorod, Boris Moiseiovich Tkach remembers that he lived with his grandfather, Itzik Meyer, who was a rabbi in town, before the war. The family had a big house where poor people always came, and the grandmother fed them.

M. Ben-Ami, a Jewish publicist and a public figure probably from the village of Verkhivka of the Podilsk province wrote about his life in Jewish places:

Here you immediately see a life full of eternal torments and anxieties, eternal fears and fears for tomorrow. Here everything lives by chance, there is not a single secure moment of calmness, not a single hour of oblivion. Everything is built on sand, which is blown in all directions by the first wind. There are no specific occupations, because no one knows what to take on and rushes at everything. Today he buys wool, tomorrow he buys corn, the day after tomorrow he buys hay or coal, hoping to sell at a profit. Others, and most of them, simply revolve around one or the other in some kind of hope, perhaps by some miracle they grab earnings of a few kopecks. For the sake of these earnings, no matter how insignificant, they are ready to swarm day, not to sleep all night, to walk tens of miles on foot, to be exposed to all sorts of dangers, to live under the eternal terrible threats of police officers. Acts, protocols, jails, fines, deep sighs, groans, complaints come from everywhere.

And yet there were Jews who had difficulty finding work. Bogrov, the demographer of the 19th century, wrote about them as follows:

With rare exceptions, these people are forced to “pull the strap” (do something risky for someone else) in a hopeless situation, since, not being accepted by the Gentiles, willy-nilly they must be content with the wages they receive from their fellow tribesmen. This category of people in most cases is honest, active and quick, but is unhappy that it often has to scoop chestnuts out of the fire for its business owners.

The life of religious Jews followed the Jewish calendar and revolved around the shul - the synagogue. The religious community had an extensive network of religious institutions that dealt with daily concerns. These institutions included the rabbi, the head of the synagogue, the head of the court, the shochet, ritual slaughterers and sellers of livestock and poultry, the parnas, who represented the community in relations with the authorities, the owners of kosher butcher shops, the mikvah or ritual bathhouse, the burial society or Chevra Kadisha, and religious communities or Chevros, that cared for people in need. The expenses of the Chevros were covered by the box tax, and these organizations may have collected dowries for poor girls and maintained accommodations in overnight shelters. The box tax was an intra-community tax on kosher meat. The regulation on the box tax in 1839 established the tax only on kosher meat, excluding “taxes… from items of Old Testament worship…”, i.e. candles and esrogim, but made it mandatory for all Jewish communities in the settlement zone. In 1872, the collector of the box tax in the town was S. Roizentul.

A shochet was a traditional Jewish profession. Not everyone was allowed to be a shochet. The butcher had to be morally ideal, exhibiting observance of all religious requirements and no drunkenness. Certification in this profession was issued by the rabbinate only after long-term completion of specific complex training and passing exams. The shochet shopkeeper had a rack in the room, on top of which there were hooks hammered into the boards, and a little below there were grooves. Chickens were brought to the shochet with bandaged legs, and he confidently took the bird's beak in his left palm, threw its head, and plucked some feathers from its throat, while whispering a special prayer. Then he made a deep cut with a knife and immediately hung it on a hook by its bandaged legs.

In the pre-revolutionary time there was also a cantor in town. In addition, famous cantors who toured Jewish towns also came to Kopaigorod. The cantor would sing Kol Nidrei, Shalom Aleichem and other songs. There were times that even non-Jewish Ukrainian residents of the town came to listen to the performance of the Jewish nightingale. Sholom-Aleichem also wrote about an extraordinary cantor who sang the songs, Yosele-Nightingale, Motl Boy, and Wandering Stars. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Soviet authorities forced all cantors to give up their activities and write applications of refusal to the tax administration.

After the abolition of serfdom, distillery plant No. 33 was built in Kopaigorod and it was owned by Feodosii Ilyich Skorobagach-Bogutskyi. The productivity of the plant was 26.8 thousand cubic meters per year. Twelve people worked there and among them were Jewish employees. In the All Russia Catalog for the year 1899, the owner's name was listed as Matryona Illivna Skorobagach-Bogutska, and her son F. Skorobagach-Bogutsky, was the manager. During the season, 22,000 buckets of wine were produced. According to the data for 1912 the owner of this distillery plant, No. 33 in Kopaigorod was the same Feodosiy Ilyich Skorobagach-Bogutska, who together with his brother, owned a significant amount of land, about 1,250 desyatin (des.) or about 3,400 acres in Kopaigorod, 1,225 des. in Kosharynsti and 800 des. in Volodiivtsi. An article in the Rada newspaper in 1907 No. 201, provides evidence that information about the brutality of the Bogutsky family was repressed (DAKhO F.6193, Op.2, Spr.10491).

Alcohol was made from corn, rye, malt, and potatoes. A pood is approximately 16.38 kg or 36.11 pounds. The production of alcohol at this plant required 26,096 poods of potatoes, 2,492 poods of malt, 560 poods of rye, and 2,660 poods of corn. There were 150 horses and 200 cattle at the factory whose manure was used as fertilizer. Crop rotation was carried out in nine fields: 1) manure, steam, 2) wheat, 3) potato, 4) beet, 5) sugar beet, 6) clover, 7) clover, steam, 8) wheat, 9) potato. (State archive of the Khmelnytsky region. – F.233. – inv.1. – ref.478).

There was a state wine shop, No. 1318, in the town. At the end of the 19th century, 40 tailors, 6 hatters, 16 furriers, 15 carpenters, 10 blacksmiths, and 10 shoemakers worked in the town. There were fifty private shops. In 1892 the following shops were in operation: N. Arzinova, Sh. Eizensharf, H.I. Eisensharf, Z. Gelen, G.I. Lisker, S. Lisker, H. Roisenblit had a shop consisting of simple manufactured goods; S. Bilenka, P.M. Hervets, H.S. Deren, P. Sklyar ran a flour shop; , R.V. Byk had a small goods store; N.G. Goykhman, M. Silbershtein, V. Roisenblit, G. Schneiderman sold small goods and tobacco products; I. Kreis sold iron products; P. Spektor had a bread shop; Silberstein Molka, H. Shneiderman and Sh. Shifman also sold small goods and tobacco products; L .IN. Kulikovsky operated a water mill; M. Lyubarska maintained a flour store as did G.I. Lyubarska, P. Oksman, H. Sklyarovskyi, and, H.S. Shneiderman; N.M. Naftulishen had a tobacco and trifle trade; S.I. Roizentul was responsible for collecting the box tax; M.Sh. Shvartsman had a grocery store; S.L. Shmucker sold leather goods; A. Bahan had a workshop to manufacture wheels. The merchant of the II guild was M. Weinberg, who had a large manufactory store, as well as haberdashery and grocery stores with an annual income of 9,000 rubles. The merchant of the II guild I.V. Grubman had a manufacturing shop with an income of 6,000 rubles. Z. Kulikovska ran two manufacturing, haberdashery, and two grocery stores. The income was 9,000 rubles. Nobleman N.O. Olszewski owned a pharmacy and his annual income was 3,500 rubles. All of them worked under the approved merchant documents which granted them the right to trade in various goods. Jews were engaged in cutting tobacco. The men involved in this at the beginning of the 20th century were Froim, Shamis, Moisha “Kabak, Smul Ostrovsky and his brother Motl.

The Khrenovets sugar factory in Kopaigorod was directed by I. Strykhojevskyi. The head of the post and telegraph department was I. Kupczyk, who worked in this position for many years.

The Mogilev Zemsky District Administration notified the Podilsk Provincial Zemsky Administration about the availability of medical personnel in the district as of January 1, 1917. Kopaigorod district: doctor M.A. Ochkavskyi, paramedic G. L. Nayriklad, and temporarily acting as a midwife, G. A. Sheinzvit-Schnerer. Yaltushkiv district: V. K. Dolynskyi, paramedics - S. N. Palamarchuk, H. G. Boychenko, and temporarily acting as midwife, G. A. Breiterman.

N. Ochkovskyi was a local doctor, A. Timkhomirov was a veterinarian, and N. Olshevskyi was a pharmacist. The doctor of the 2nd ward was N. Zhylynskyi, who in 1895 was transferred to the city of Haysyn to the position of district doctor. A. Patrikeev worked as the head of the Kopay railway station. The town mayor at the beginning of the 20th century was Leib Velvl Kulikovsky. He treated people from various diseases, even though he was illiterate. And in 1904, Tsal Duvydovych Brickel-Grinberg was elected a mayor. Fyodor Gontar was the parish foreman, and Ivan Navrotsky was the scribe. In 1904, the village headman was N. Kukuruza. Mykola Ochkovsky was in charge of the hospital, Neiman Kazimir was the doctor. Mykola Olshevsky worked as a pharmacist. In March 1910, the Kopaigorod headman was arrested by order of the prosecutor for a number of official frauds. In the period 1897–1912, M. Vainberg and I. Sklyar engaged in large-scale manufacturing trades. I. Barshtein ran a pharmacy. Groceries and consumer goods were handled by M. Zilbershtein and I. Weinbrook. The crockery shop was owned by R. Hazhiman. N. Step was engaged in egg trade. A. Moreinis was engaged in the trade of flour and eggs. Villagers brought their products to Morainis' store and wholesalers came to him from big cities and bought everything. This was the pattern of trade. Kerosene was sold first by M. Weinberg, and later by J. Lifshitz. D. Schwartz was engaged in timber trade. L. Navrovsky worked as the head of the Kopaigorod station.

At the end of the 19th to the early 20th century the mill in Kopaigorod was owned by M.H. Balashov. Balashov was a member of the State Duma and the leader of the nationalist faction. To illustrate his significance, he once claimed at a meeting that if he wanted, he could move the county center from Yampol to Kopaigorod. When he was told that the transfer of county institutions was an expensive measure, he said that he would give his money to the cause. The administration of Yampol was frightened and appealed to the government to leave Yampol as a county town. In response, the government said that there were no plans for such changes and that this was just Balashov's statement.

The building of one of the synagogues still exists today. This building was equipped as a cultural center. The synagogue was the best building in Kopaigorod. Inside there was a large hall with biblical paintings. At first glance, the synagogue was small, but inside the rafters were elevated with a high ceiling. The synagogue was not supposed to be higher than a cathedral or a church, as stated in the building permit at that time. Near the synagogue was a heder school, where the boys were cramped and suffocated all day in an unequipped building where they studied Torah and Talmud, each one reading individually and aloud, all together. The study of prayer had to be done out loud or in a low voice.

Jews from Kopayhorod took part in the Russian-Japanese War of 1904. Leib Reutman was wounded, returned disabled, survived the civil war, and died in the ghetto in 1942. Moisha Ruvinovich Perelman had served in the cavalry dragoon regiment, and was awarded the St. George's Cross of the IV century. When he came to the synagogue in Kopaigorod on Rosh Hashanah with this award, they did not want to let him in. A rabbi interfered and said that it was not a cross, but an award for meritorious service in the war, which he earned with blood (from an interview with Perelman's grandson, Ruvin Hitman, in 2002 in Chernivtsi, the interview was conducted by Olena Levitska).

The townsmen, Spivak and Farber, were disabled from childhood, but decided to make extra money from the military draft. In 1909 they came to the Khotyn conscription station to apply as healthy recruits. After their fraud was discovered Spivak received five months in prison, and Farber, eight. In addition, the prosecutor wanted to prosecute the Kopaigorod headman. (Rada newspaper for 1910, No. 26).

During the First World War, out of 13 lower-ranking Kopaigorod residents who died at the front, there were five Jewish soldiers: S.Sh. Bogomolnyi, G.Y. Magdalenik, H. Shleiter, Z.R. Spivak, corporal M.M. Vonyar; wounded at the front: Z.S. Shister, L. Shusterman and others.

In 1911, the Provincial Committee on Small Credit gave permission to the Jews, to open a savings and loan society, which began operations in 1912. According to the 1913 directory, All South-West Region, Jews owned many business enterprises including the following: both warehouses of pharmacy goods owned by H. Baron and Sh. Barshtein; all seven grocery stores, owned by Ovshii Vaindrukh, Zus Gelin, Meyer Golman, Michel Goldman, N. Deren, Elya Kozak, Moisha Korenfeld; all three haberdashery shops owned by Meyer Bogorochyn, Feiga Mestman, and Rivka Shor; all 3 hardware stores owned by Sura Kerstinetska, Ruhlya Maltser, and Zus Sharfer; all three stores that sold leather products, owned by Shmul Monovich, Nadia Spektor, Abram Shmukler; all sixteen manufacturing shops, owned by Mendel Eisensharf, Dvoira Beyrichman, Ruhlia Bidna, Menashe Weiberg, Raizya Verega, Zeida Gelin, Iol Kerstynetskyi, Itzko Malzer, H. Naftulishen, Bluma Nischa, Shariy Spivak, Mirli Zvitman, Haim Shoikhet, Nuhim Shilson, Haya Shilson, and Etya Erlichman. Bruna Molka owned the only clothing store. The single kerosene warehouse was owned by N. Degen, and two warehouses for timber were owned by Ihil Oksman and Dan Schwartz.

Oksman was a rich merchant, engaged in the timber trade. He also owned a plot in a forest in Bessarabia, which he purchased at the beginning of the 20th century. Eva, was one of Oksman's daughters, attended the Bar Girl's Gymnasium from 1915–1918. She lived in an apartment in Pildesh in the city of Bar. She was arrested in 1938 and prosecuted for illegally crossing the border between Poland and Romania and received a sentence of ten years in the camps. Eva completed her term and returned to Kopaigorod in 1948, after which she lived in Murovani Kurylivtsi. She was rehabilitated in 1956.

|

|

The ten bed, rural hospital in the town was opened in 1892 by the zemstvo, which provided free medical care in the hospital and in the outpatient clinic for all those who applied. In 1901, 11,564 people, mostly villagers from the Kopaigorod medical district, visited the town's dispensary. In 1912, the zemstvo built a new eighteen bed hospital building with a staff of seven. Houses for doctors were also built at that time. There was also a paramedic station in the town and F.A. Stakhov worked there as a paramedic. There was another so-called doctor, then, who lived in Kopaigorod near the hospital. He treated people's diseases even though he was illiterate. In 1923 the hospital in Kopaigorod was expanded to thirty-five beds with separate clinics. In 1958 the hospital numbered fifty beds. In the period 1959–1989, the chief physician was E.N. Zhuchenko. The Kopaigorod district hospital was named after V. I. Lenin even before the war, sometime in the 1930's.

|

|

The construction of a new, two-story medical building with one-hundred beds was completed in the 1970s. In 1960, the polyclinic was located in a separate building with ten offices, but in 1997 it was transferred to the first floor of the district hospital. In 2001, the hospital employed nine doctors and fifty-one mid-level medical personnel.

In 1912 several Jews from Kopaigorod were included in the lists of voters of the Podillia province to the State Duma: M.B. Korenfeld, A.Z. Strahm, M.A. Ehrlichman (DaViO F. 37, inv. 1, ref 8).

In those distant times, the Jews gave their names to the streets of the town: Shevska, Kravetska (tailors lived there. AR), Blyakhariv (tinsmiths lived there. AR), Myasna (butchers lived there. AR), Zolota (jewelers lived there. AR) and others. The names of the streets were related to the professions of the people who lived on that street. The street where the main synagogue was located was called Shil Gos or Synagogue Street, which is near Golden Street. Jews always liked to gather there during their free time and on holidays.

It was easy to quickly recognize who was a Jew in the streets of Kopaigorod. Elderly people always went outdoors wearing a cap or a hat; they did not walk with their heads uncovered. In pre-war Kopaigorod, some believers went to the synagogue in traditional Jewish clothes. Usually, elderly women walked behind their husbands. They could only be seen together at a wedding. Young Jews no longer behaved like that, even though their parents taught them the traditions and customs of their people. The names given to them were still Jewish for many, but certainly not for all. In the store or at the bazaar, the woman decided on everything for purchase, and the man paid for it all, and even if he did not like something, it was useless to speak. One would never see a man buying something for himself or for his children. Only the woman bought clothes and shoes for the whole family. You could watch how women in the stores threw all the goods around until they found what they needed. They even tried to bargain as if they were at the bazaar.

Jewish families had many children. For example, my grandmother's parents had five children. Avram Moreinis, who was called “Black” because he was dark-skinned, had seven children. After the death of his wives, he married a second and a third time, and he had ten children altogether. Most of the Jews were artisans and lived in poverty with their large families. Various industries were developed in the town, and trade flourished, yet Jews were forbidden to own land. Everything one needed in the town and surrounding villages was available. There were potters, carpenters, cobblers, tailors, hatters, coopers, blacksmiths, bookbinders, jewelers, hairdressers, millers, painters, and carters. There were a dozen shops on Golden Street near the synagogue providing groceries, leather goods, jewelry, perfumery, and others. Life was boiling here on this street. The income in the town for the year amounted to 140 thousand rubles in gold. Everyone knew the four blacksmiths of the Blechman brothers, the hatter Koifman, the tailor Shtivelman, the oilman Kalman, Belenky's flour warehouse, Sheiva's woolen goods shops, Kodner's leather goods, Shmukler and Z. Vinokur's blacksmiths, A. Oksman's inn, K. Bidny's grocer and much more. One of the artisans was the tailor Fishilevich. U. Avis learned sewing from him at the beginning of his career. Many shops were located on P. Demenchuk street (the modern name of the street).

The life of the Jewish community of Kopaigorod was described by Motl (Mordko) Avrumovych-Shomshenovych Ostrovsky, who was born in 1902. He lived in the town and moved to live near his son in Tula after he retired. In 1977, he wrote a memoir in Yiddish about Kopaigorod and his family. Motl had studied in several schools, he was a tobacco cutter, then a barber, survived the occupation, fought, reached Prague, and was demobilized in August 1945. His son, Oleksandr translated his father's Memoirs and Diary, which date back to 1912-1913:

My great-grandfather is Leib-Shtiglik. Why did they give him the nickname Styglyk (Goldfinch)? Because he really loved the goldfinches; they sing beautifully. His last name was Mareynis. I remember a little about him. I was six or eight years old. He had a white horse that used to graze on our meadow in Kopaigorod, a small town in the Vinnytsia region. There, on the levada, a grove that often flooded in the spring, there was a ditch for water that accumulated after flooding as a result of heavy rain. This horse fell into a ditch and could not get out. The great-grandfather was standing and crying, burning tears, because he could not help her: “Oh, what will I do without my horse? This is my whole life. The horse is feeding me!” I don't know what my great-grandfather did for a living, because at that time I didn't think to ask my parents about his profession, as at that time I didn't know that I would write about it someday. Well, people took pity on him, and with great difficulty helped to remove the horse from the ditch. It was a holiday for my great-grandfather.It was said that he was a cheerful person who loved jokes and funny stories. He built a house for himself and made large windows in it. In those years, in small shtetls, when people built houses, they made small windows. And the neighbors asked him:

– Mister Leib! Why are you making such large windows, in winter you will freeze?

He answered with a smile:

– I am making large windows because I don't want my children to be liars after my death. When I die, they will mourn me and say: from such a bright world at home to a dark grave. Therefore, I am making large windows.

Great-grandfather was short, with a long white beard. Unfortunately, I don't know anything more about him. I don't remember my great-grandmother and I don't even know her name. But I know that she had two children, a son and a daughter. The son's name was Peisya, but I don't know the daughter's name. Peisya, that is, my grandfather, was the father of two children: a daughter, my mother Malka, and a son, whose name was Avrum. Peisya's grandfather died young. His wife, that is, my mother's mother, was called Khaya, Khaya-Black, because she sold paints and was always stained with black paint, but she also had a dark complexion and dark hair. In addition to paints, she sold nuts, and walked around the market, casually knitting wool clothing. When I visited her house, there were always sacks of nuts. I used to make a small small hole in the sack, pull out the nuts one at a time, stuff my pockets full of them, and run away. I regretted having done this when I got older, because I realized that my grandmother was very poor. She died at 66 years of age. Her whole life was spent caring for children. She was a young widow and remained a widow during her life as she raised her two children.

My uncle Avrum Mareynis, or Avreimla, was also nicknamed the Black (as his mother Khaya the Black). And my mother in Kopaigorod was called Malka-Khaya-Shtigliks. Grandmother Khaya had to support her grandchildren as well. We had eight children in our family, and my uncle Avreimla had seven. Fifteen grandchildren! It is clear that where there are many children, you need to cook a lot of food.

My father's name was Avrum-Shomshen, two names. This was the custom at that time. They gave two names to almost all the inhabitants of a small town. As I have said, there were eight of us including five brothers and three sisters. Their names are: Pesya, Mendl, Nakhmen, Shmil-Arn, Mordha-Gersh (this is me, the writer), Esther, Bella and Leibele. What work was my father doing? He was buying the harvest in the bud: apples, plums, borrowing money at interest from the peasants in the spring, when the trees were just beginning to bloom. If there was luck and there were no early frosts, the orchards produced crops. My father harvested the crops and set up his equipment to dry the plums. Apples were intended for storage, for which my father rented a basement. But first, the apples lay under the trees for a whole month in piles. In late autumn they were brought to the town, waited for buyers and sold. Dried plums were packed into barrels and also sold.

But this happened only when there was a harvest, so they risked borrowed money. And if suddenly there was a frost, everything was gone.

Why did the father have to take such a risk? Why buy a crop in bloom? The fact is that there were many buyers, and everyone strove to be the first, to grab a tidbit earlier. They broke their necks more than once, remained in debt, starved for the whole year and folded money to repay the debt.

Father had two more professions. He rented a hectare of land for planting tobacco, grew it, then cut tobacco leaves, dried and sold them at retail. At that time, the law prohibited the sale of tobacco, and it was sold secretly (I will talk about this later). The land rented from the peasants was uncultivated and provided only a poor harvest. What kind of peasant was it, if he, the landlord and owner, or balabus would lease good land? Only the lazy one who doesn't want to work can do it. In childhood, almost all of us (the elders dispersed around the world) helped our father, worked with tobacco. I will not explain in detail how to grow tobacco, and process it. I remember well that it was hard work, it was especially hard to work on the plantation.

Selling tobacco was my mother's job. Peasants, our customers, gathered in the house, especially on Sundays, sat with relish as they slowly lit up a spin. This is how they tried the strength of tobacco. They were smoking and spitting in all directions on the ground, our clay floor. There were other sellers, competitors, with whom we had to fight for customers. Yes, another attack! As I have already said, it was forbidden to sell tobacco, so that at any moment the controllers could rush in, breaking into the house, and if they found even a little, for example, 10 g (a loit), they wrote an act and the case was taken to court. They were judged harshly for selling tobacco. For the smallest amount they were given a prison term or fined. My mother, according to her stories, spent a month with me, two years old, in prison, in Luchintsy, a small place near Kopaigorod, because she had nothing to pay the fine. Imagine being in jail with a small child!

Despite all three of my father's “professions” we never got even a piece of bread. There was no question of wearing pants or a skirt. We were ragged, barefoot, and always hungry. Despite the fact that all families lived in poverty, they always had many children. Religion forbade having few children. We had eight children, and two more died very young. My mother was very kind to her children and we loved her very much. She never paid attention to herself, she gave everything to her children, only to them. And because she lived so poorly, she died young, at fifty-two years old. She never had decent clothes. Our father, an Orthodox Jew, considered such a life as the order of things and was a real ascetic. He used two pairs of tefillin when praying, read the Torah on Saturday in the synagogue, and on Saturday morning he always dipped in the mikveh pool like a real orthodox Jew. Although the father was known as a devoted husband, the whole burden of earning this family's living, or parnassah, was borne by the mother. The proof of this is that it was the mother who was in prison, and not he. There would not be enough paper to describe everything that my mother went through, that's why she left us so early. I write this with pain in my heart, remembering how my mother lived her short life. My father didn't drink honey either. He went to the synagogue and sat there with his friends until night. I remember my mother told me that eight days before my sister's wedding, my father came from the synagogue and said:

- Malko, let's go make a list of who to invite to the wedding.

The mother stood up as if she had been buried, and tears were falling from her eyes. He is making a list, but why doesn't he ask where I got the money for the wedding?

This is how the life of the Jewish community is briefly described in the example of the Ostrovsky family. There were many such families in the town and they survived as best they could in those difficult times of the beginning of the 20th century.

From the beginning of 1917, the Kabardyn Cavalry Regiment of the Caucasian Division was located in Kopaigorod. This regiment was transferred here from Bessarabia and commanded by Colonel V.D. Staroselskyi. On May 24, in Kopaigorod, the Colonel addressed the staff in connection with his transfer to another regiment. Revolutionary events in Petrograd also affected discipline in the regiment. February 1917 united Kabardyn soldiers and local proletarians. Revolutionary agitation in the regiment was carried out by Cherepanov and Yagodinov. At that time, a demonstration of the local population and part of Kabardians began here. It was severely suppressed and the arrested demonstrators were sentenced to execution, which was scheduled for February 26. But Yagodinov managed to escape and bring a detachment of revolutionary-minded soldiers from Odessa. This is how the detainees were saved. In July 1917, the regiment was withdrawn from the town to the front.

In the Podolsk province at the beginning of October 1917, offenses occurred, the scale of which became irreversible. The Ukrainian Central Committee demanded that the provincial commissar organize urgent measures to combat anarchy. Similar events took place in other provinces of the Right-Bank of Ukraine. The newspaper Nova Rada of October 17 described the picture of devastation:

From everywhere, and most of all from the right side of the Dnipro, the provinces of Podilska, Volynska and Kyiv, desperate telegrams are sent to the General Secretariat that a terrible anarchy has set in, there are lootings, destruction of public goods and massacres. Pogrom excesses even arise, when attempts on the welfare and life of the Jewish people are made, as it was in the old times, and in general, pogroms of private property, individuals and groups of humanity have become a common phenomenon, and the consciousness of impunity for evil deeds gives thieves unprecedented courage. “The land becomes a victim of a calamity, severe, more terrible than war and pestilence”. This situation has become a reason for the fact that on September 29, 1917, the commander of the 7th Army declared martial law in Lityn, as well as in Letychiv, Derazhnia, Yaltushkiv, Kopayhorod, and Zhmerynka. “By order of the commander, I inform you,” said a telegram from the army headquarters, “that one regiment of the 11th Cavalry Division is being sent to Letychiv and Lityn to assist the civil authorities. The communication of these regiments is through Letychiv and Lityn.

On September 21, 1917, a very important process related to the nomination of candidates to the All-Russian Constituent Assembly began in Mogilev District. The district committee of the Peasants' Union together with Ukrainian military delegates was dealing with this issue. With their participation, on September 22-23, meetings were held in Kopaigorod, Luchynets, and other parishes. In October, pre-election campaigning and trying to solve organizational issues began. P. Tkach personally dealt with the search for parish instructors and the organization of campaigning courses in Kopaigorod and Kosharinets parishes. On October 22, in Mohyl povit, local election meetings were held, at which candidates for the people's assembly were approved. In Kopigorod Volost, the meetings were scheduled for October 23, and they were to be conducted by P. Tkach. On December 30, peasant gatherings were held in Kopaigorod Volost. Thus, in the late autumn and early winter of 1917, many important events took place in Mogilev District, which had a direct impact on the development of the social and political situation in the region, including Kopaigorod. The most active social group was the peasantry, which repeatedly gathered at forums of various levels, in which the Jews of the town also took part.

On the basis of the Law of the Ukrainian People's Republic of December 2, 1917, “On the Formation of Jewish Public Councils,” elections to the Jewish Council began to be held in small towns, including Kopaigorod. These councils were state institutions. After the election, it was necessary to send election documents for approval to the Department of National Self-Government of the Ministry of Jewish Affairs.

Residents of Bar, Kopaigorod and other towns signed the appeal of the Central Rada “To the Ukrainian people,” which called for the organization of various types of unions: political, economic, cultural, in order to support the new government. So, on October 23, 1917, a meeting was held in Kopaigorod, at which they decided to create a peasant union.

On November 1, 1918, the Mogilev-Podilsk chief reported to the provincial chief that the principal of the Kopaigorod Gymnasium, Feodosiyev, expressed dissatisfaction with the existing system in his speech at the school.

We had been working for 50 years to wait for the separation of Ukraine from Russia, to be an independent state. Since the disconnection of Ukraine, all power has passed into the hands of the people, and all goods must also be passed into the same hands. Thanks to our lack of culture, darkness, we could not prevent the revolution. Now we must learn to prepare for the next time to be able to keep the power in our hands.

|

|

Kopaigorod on Podillia.

To the local council for Jewish community. |

On February 19, 1919, Anton Romorny, an active participant in the revolutionary events in the town, was appointed as a parish commissar in Kopaigorod. S.F. Zabavskyi (1872–1956) worked as the head of the revolutionary committee. In the 1920's, the head of the village council was Vakhnytskyi. In the period of July 21-22, 1919, the battle for Kopaigorod between the troops of the Directory (3rd Iron Division) and the Red Army took place. Fighting continued on the streets of Kopaigorod. The Red Army retreated and Petliura's troops captured the town. Bukovynsky Kurintook part in these battles. The following was related about the battles:

It was said about it as follows: “The first battle, or its first battle baptism, as part of the 9th Rifle Regiment, was led by Bukovinsky Kuren for the village of Mynkivtsy and the town of Novaya Ushytsa on June 13-14, 1919. The Bukovinsky Kuren riflemen demonstrated the best qualities of fighters and proved to the rest of the units of the 3rd division that the Kuren will be a faithful and reliable brother-in-arms.Further, the shooters of the Kuren (military and administrative unit of Cossacks), in exemplary order and discipline, advanced on Verbovtsy, Murovani Kurylivtsi, Kopaigorod, Dzhurin, Yaltushkov, Maryanovka and Barok. In Kopaigorod, Bukovynskyi Kuren was fighting a fierce battle with the enemy, who, in a counterattack, occupied part of the city and began to fire at the Kuren from the behind. The commander Emelyan Kantemir, seeing the threat to the Kuren, hastily brought in the detachment of M. Lupashka, who was in reserve. He went on a counterattack and with a sudden maneuver, knocked out the Bolsheviks from Kopaigorod. In this battle, three shooters of the Bukovina Kuren were killed and several more were injured.

The command of the division highly appreciated the combat action of the Bukovinian shooters: “The serious battle on the streets of Kopaigorod and its environs ended in a complete victory for our shooters. The 9th regiment once again showed extraordinary combat capability in general, and the Bukovinsky Kuren (attached to the regiment) in particular.”

Then pogroms against the Jews began. Twenty-two Jews died as a result of a pogrom by the Blue and Iron Divisions on June 25-30, 1919. Oleksandr Ivanovich Kashchenko, who organized these pogroms in the town was appointed a deputy commandant of Kopaigorod. Many houses and shops were looted, many Jews were maimed, beaten or killed. When the pogrom ended, the Jews walked around the town and did not recognize it. The streets were covered with feathers from pillows and duvets, which the Petlyurians split open with bayonets, looking for jewels. Windows were broken in many houses. An alarming long silence hung over the town. The Jews had already begun to get used to it. The windows were gradually inserted, the broken doors were repaired. Some victims of pogroms in Kopaigorod in the years 1917–1920 were: L.S. Dats, J.S. Fefer, L.Sh. Fishylevich, S.B. Herman, L.V. Horodetskyi, A.A. Cat, V.A. Horodetskyi, H.A. Kisner, L.G. Meyerovych, E.A. Ostrovsky, M.A. Sherman, Y.A. Schneiderman, M.M. Schneiderman, Y.B. Schwartz, I.H. Solomon, A.O. Spector, H.G. Yankelevich and others (DAKO F-3050. Op-1). During this period, Jewish self-defense was organized in the town, to which many Jewish boys signed up, including Shmul Ostrovsky. The guys took turns every night and gathered in the synagogue. There was an incident with Shmul when he accidentally shot into the ceiling of the synagogue. And then it started! Shooting in the synagogue!

|

|

The ministry of justice |

Regarding the pogroms in 1919, Motl Ostrovsky said in his memoirs that when the Petlyurians entered the town, they first began to search for communists or those who served the Bolsheviks. Of course, this did not happen without the help of traitors. They shot a young guy, Yankif Fefer. They also looked for Shmuel, Motl's brother, who was with the Reds. They did not find him, so they arrested Motl and brought him to the headquarters located in the village Maryanivka. Motl was kept for three days, beaten, and sent with other prisoners to Novaya Ushytsa. He was imprisoned there for three weeks and beaten there as well. Thanks to the connections with the military by a Kopaigorod merchant, Yan Weindrug, who lived in Novaya Ushytsa, many people managed to escape. All the people from Kopaigorod were released, but Motl and several others were not. They wanted to prosecute him for his Bolshevik brother. However, they let him go after a few days, because the Red Army broke through the front and Petlyur's troops hastily retreated.

The Ukrainian authorities took certain measures to stop anti-Jewish pogroms. The perpetrators of pogroms were shot.

In the materials of the history of the Army of the Ukrainian People's Republic, Oleksandr Vdovichenko wrote in 1919, that after Kopaigorod, the attack on Mohyliv began. And here the Bolsheviks organized a large regiment of partisans from among the peasants of Nemia, Serebria, as well as Kopaigorod, Ozarinetsk, and Mogilev Jews. The 9th Rifle Regiment of the Ukrainian People's Republic was able to defeat this regiment and approximately 200 Jews were captured. During this time a gang passed by and tried to organize a pogrom against twelve Jewish families in the village of Karyshkiv. But the Ukrainian peasants who lived there, came out and said: “These are our Jews. And whatever we want, we will do with them, but we won't allow you to let even a hair fall from their head, if you want to stay alive.” And the peasants drove them away. It was such a unique case. The village is not close to the railway and far away from any roads. This is a place where if thieves get lost and try to steal food, they are stopped. In the same year, the grain department of the Ministry of National Economy of the Ukrainian People's Republic ordered the Mogilev production department to give the necessary amount of bread from the new harvest to the robbed population of Kopaigorod.

|

|

From Udovychenko, A.I. Third Iron Division. Ukrainian Publication Cooperative, Inc. New York, 1971. Source URL: https://coollib.cc/b/181628/read Alternate URL: https://textbook.com.ua/istoriya/1475056229/s-17 |

Three riflemen from the Bukovinsk Kuren were killed in this battle, and several more were wounded. Many Jews fought in the 3rd Iron Division, particularly in the positions of sergeant and foreman. It is known that three of them died. It was in this division that in 1919 the legendary Semyon Yakeroson from Vinnytsia fought. There were probably Jews from Kopaigorod and Bar in the division. According to one of the kurens of the division (probably Buovynsky), several sub-chiefs of the Cossack Jews served and took part, along with others, in all the battles of the unit in July of the same year. In Mogilev, this kuren buried Aron Stolyarskyi, one of his Jewish sub-chiefs, who died from his battle wounds. He was, according to the kuren, an exemplary ideological Cossack, a well-known Ukrainian and showed good hopes as a good soldier.

The speech at Aron's grave was delivered by a fellow soldier in Hebrew, with elation and strong feelings, and included a call to the Jews:

You - Ukrainian Jews are standing over the corpse of Aron Stolyarsky. You are standing and thinking, how is it possible that a Jew can serve in the Ukrainian army? How is it possible that he went together with them to fight for some ideals of the Haidamaks (popular Ukrainian rebels) ? How can it be judged for the Ukrainian cause? The blood of Aron Stolyarsky testifies here, in front of you, that it is possible, that it should, that it is necessary! We, the Jews, need this first! We need it ourselves! This is the only truth that we Ukrainian Jews must understand and follow.”

|

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kopaihorod, Ukraine

Kopaihorod, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 23 Jul 2025 by LA