|

[Page 191]

|

[Page 192]

|

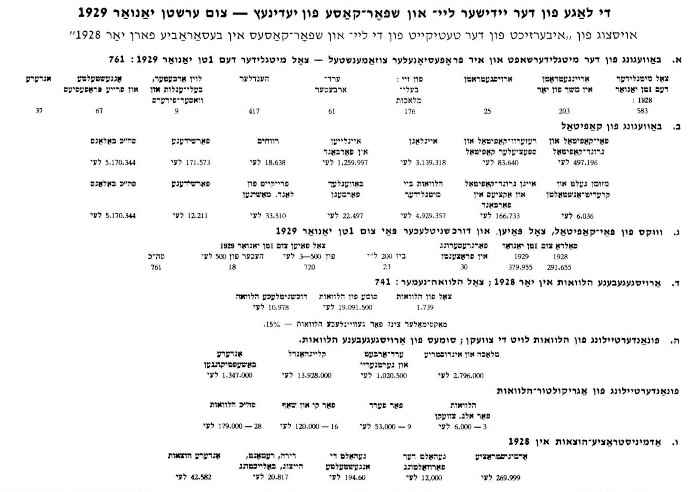

Extract from the report on the activities of the Loan and Savings Fund in Bessarabia prior to 1928

Translated from the Yiddish by Ala Gamulka

Members 1/1/1928 – 583

Funds on hand – 497,196 Lei

Cash on hand and credit institutions – 6,036 Lei

Remaining balance as of 1 January Growth of interest – 30

Payments by 1/1/1929

Number of loans – 1,739

Artisans and industry – 2,796,000 Lei

Distribution of agriculture loans

Administration – 269,999 Lei |

by Shalom Caspi-Serebrenick, Herzliah

Translated from the Yiddish by Ala Gamulka & David Goldman

Donated by Yvette Merzbacher-Bronstein in memory of her great-grandparents Asher (Froykes) and Rachel Kaufman (Koifman)

and her grandparents Yoil and Liza Bronstein, buried in Lima, Peru (daughter of Asher and Rachel Kaufman, Yedinitz)

According to the last Romanian census of 1932, there were a total of 6,000 Jews in Yedinitz on the eve of World War II. Over the generations, Jews lived in relative calm and earned their livelihoods making more or less money in business and trades and yet others in agriculture and small industries.

Since we do not have exact statistics about the branches of livelihood of the Jews in the shtetl, we cannot possibly do an overview. We did receive some information about the Yedinitz Savings Bank from the Organization of Savings Banks in Bessarabia (headquartered in Kishinev) for 1928.

There were 761[1] members in the Yedinitz Savings Bank in 1928. Among them, 176 artisans, 61 farm workers, 417 merchants and shopkeepers, 9 wagon drivers, water carriers and daily wage earners, 67 free professions and officials and 37 others. Although most of the townspeople were members of the local Savings Bank (also called “help” bank), one can imagine that the division by occupation (in the Savings Bank) can give a true picture of the general division in the shtetl. From this data, we can see that the merchants constituted the majority of the income earners with 417 out of 761, making over 54%. They are followed by the artisans (176, equivalent to 23%), officials and free professionals (doctors, pharmacists, lawyers, teachers, religious personnel, etc. — 67, equivalent to 9%), farm workers, etc., 8%;

[Page 194]

others: 194, equivalent to 5%. The last on this scale were wagon drivers and water carriers, only 1%. However, this group really represents a larger part of all income earners. They were not necessarily members of the Savings Bank. These people would not take commercial loans from the Savings Bank, but they actually represent about 5% of all income earners.

The above-mentioned overview of the occupations of Jews in Yedinitz is given separately. It is condensed and is probably incomplete.

Agriculture

Truth must be told that the Jews of northern Bessarabia, unlike the Jews in the center, were less inclined to work the land themselves. The farm workers were referred to as “passersby” in the fields.

[Page 195]

We must mention the following names: Yaakov-Shimon Koifman and his sons; Naftali Terebner, Shmuel Drutzker (those named remind us of the villages where Jews worked the land or came from); Shmuel Frodis, Meir Boim, Israel and Shmuel Koromonsky, etc. In each village there were people on whom the owners could depend on. These people supervised the work, provided machinery and tools, arranged for transport, looked after sowing, etc. The working hands were local. In busy times, workers were brought from distant northern Bessarabia.

There were also lumber dealers who sold wood locally or sent it further away. It was difficult to keep it in town. Shmuel Kafri (“Kafri” means villager) tells us that the lumber dealer Eliyahu Meilechson established a yard in Mogilev. He became wealthy from this business. In his will, he left funds to be distributed to poor people. On the day of his yahrzeit, money and heating wood worth 300 rubles were given out.

|

|

Audit Committee Directors. Founded 10/17/1926. 1. Asher Kaufman (Froykes) 2. ---- 3. Hillel Dubrow 4. Aharon Bronstein 5. ----- 6. Meir Walevitch 7. Yechiel Nemichinitser 8. ---- 9. Yosef Speier 10. Yankel Moteses Schwartzman 11. Shmuel Ludmir 12. Itsik Yaakov-Shayas Greenberg 13. Attorney Yisrael Korman 14. Yosef Riesman 15. ---- 16. Lyovo Gukovsky 17. Mina Parnes (Yisrael), 18. Raphael Cooperman |

As to the land worker, we must mention those nicknamed the “Bulgarians.” The most important among them were Berl (Dudel's) and Mordechai (David's). They grew vegetables near the “lakes” (actually standing water) behind the gardens and houses on Patchova street (Post office street). Berl's was near the wealthy man's lake. Mordechai was near the seminary lake. They built a primitive watering system using a wheel. Pipes hung from the wheel and were lowered, full of water, spraying the field. Horses turned the wheel. There were hundreds of fields and many workers. Gentiles did the sowing, watering, and harvesting while Jewish workers, mainly women, dried the tobacco leaves. Drying and cutting the leaves was a special task.

There were also the wheat handlers. They had stalls at the entrance to town and bought the wheat brought in by the farmers. The wheat was then sent to larger centers of wheat trading. Some wheat was for local consumption and the rest was for export.

[Page 197]

There were also Jews who filled sacks with wheat. Some sacks needed to be mended.

Artisans

As a rule, each group of artisans lived in separate sections in town. There were the Tailors Street, the Shoemakers Street, etc. There were areas for butchers and blacksmiths, as well as for lumber dealers.

There was no occupation in which Jews were not involved. Let us list them: tailors, dressmakers, shoemakers, fortune tellers, poets, carpenters, construction workers (there were gentiles among them) and also locksmiths, blacksmiths, glaziers and coppersmiths (they repaired urns, cooking elements and recovered utensils), jewelers, goldsmiths and watchmakers, painters, butchers, fishermen, bread and bagel makers. One occupation lay mainly in gentile hands - construction. However, the finishing (carpenters, glaziers) was done by Jewish artisans.

[Page 198]

By the way, everything related to electricity was completely a gentile occupation. The only electrician was Aliosha who worked in the electric station. He proved himself to be a murderer during the Holocaust (as were most of the gentiles who had lived among the Jews and had earned their living from them. I.e., gypsy musicians). The four mechanics were gentiles.

Some of the artisans employed experienced workers as well as apprentices. The latter were paid according to the “time” (semi-annually, Passover to High Holidays, or Sukkoth to Passover).

Some artisans only served the Jewish population, but some of the gentiles were better workers. The Jewish tailors were Yitzhak-Leib from Brichany, Michel-Meir Hirsh, and Izzy, etc. Among the women's tailors the following were well known: Mordechai Sheindelman, Motya Lipcaner, Avraham Khotiner and others.

We should also mention those whose unique specialty was to sew priests' robes.

[Page 199]

Among the shoemakers let us mention: Noach Sandler, Zecharia and Meir Leyzer Hersh and others. Mainly, the artisans served the villages nearby. The well-known foremen were Meichel and Moshe Kerik, Hersh Zagatovtchik (foreman) and others. The best carpenters built furniture for the wealthy. We remember Koppel Stoliar, who was also an instructor in the Hechalutz chapter in the early 1920s. Before WWI, among the bakers were the “Turks” and “Greeks.” They disappeared with the Romanian occupation. The bagel bakers produced bagels for the market. The gentiles bought them as delicacies – for the sick. A famous bagel maker was Tchernopoi-Guttman (father of the writer Rachel Tchernopoi-Guttman and other girls, members of various organizations). The workers were the pioneers of professional organizations (the unions). The organizer was the owner Tchernopoi-Guttman. They held the first strike in town even before WWI. The picketers came out of the bakery onto the Brichany road in order to stop the strikebreakers.

On the other side of the street, near the bakeries, on the way to the sextons' synagogue (although they were mostly butchers), one could find the butchers and the skinners. They were a caste of their own. They were always among the first to protect Jewish life in troubled times.

There were fishermen who brought fish from the rivers on Fridays. The rivers belonged to wealthy people. The fish caught were mainly types of carp. The leftover fish, not the fresh one, would be bought, later, by the gentiles.

Let us not forget the barbers. They were classified according to the hygienic protocol. The well-known ones were Meir the barber, Yitzhak-Yoine and Avraham Bromberg. In the 1930s, the most famous was Mendel Polliak. He had devised a method of conducting water into bowls to wash the face and the head. The hat-makers and furriers should not be ignored. The latter occupied themselves mainly by sewing furs for the gentiles.

[Page 200]

Shopkeepers and Merchants

As there were among the artisans, there were also “finer” people among the shopkeepers. They served the Jewish community and the gentiles. The majority had cheaper goods for the gentiles and the poor Jews. Among the fashion shopkeepers we remember: Yaakov Perlman, Samuel Galperin, Menashe Vineshenker, Yosef Eidelman, Velvet Kolebelsky. Among the better shoemakers were Yitzhak Hirsh Tchok, the brothers Dudel and Nissel Kolker, Aharon-Bee Gershl. Among the grocers: Moshe Gendelman, Avraham Zilberberg, Yechiel Klugman, Leib Hochberg (from Odessa). Mindel Freilich and others sold housewares.

The bigger part of commerce, with the gentiles, took place in the marketplace.

|

There were bartenders who were not too shy to use the situation. They would cite conversations between Shenkar Gruin and his son Getzl (made up names).

– Getzl, did you settle the bill with the priest? The trick of putting out again was easy to learn. However, Getzl was an obedient son and when it came to settling bills with drunks, he put out again. |

[Page 201]

In the marketplace one could find the “sitters”- men and women who offered fruit, the “Bulgarians” who sold vegetables, fishermen, bakers, etc. In the lower market near the church, there was a row of Jewish stores with cut goods, ready-made dresses, haberdashery, shoes, metal wares, paints, groceries and gifts. Here, too, were other vendors. Some were gentiles. They sold agricultural products, milk, cheese, sausage, pork meat and fat, etc.

The alternate marketplace was also called the Horse market. This is where horses and other animals were sold or bartered. Until the Romanian occupation, this was also the place where there was an annual agricultural exhibition and where villagers spoke of their miracles.

During the Romanian occupation, the animal trade was moved farther out of town. There were special places for trading horses, pigs, cattle, sheep, etc.

|

|

[Page 202]

In 1941, the special places for the animal's trade were used to concentrate the Jews from Bukovina and northern Bessarabia brought there by the Romanians and Germans on their way to Transnistria. By then, there were no Jews left in Yedinitz.

There were pubs around the marketplace and they were filled with troublemakers and drunks. After selling their goods, the troublemakers would go to the pubs to wet their throats and strengthen their hearts. Many became drunk like Lot and would spend all the money they had earned from their sales.

Pharmacies

The first pharmacy was opened by Levental, who came from “deep in Russia.” The pharmacy was in a building that later became the Shaarei Zion synagogue. Levental quickly became wealthy and moved the pharmacy to a building on Patchova street. It later became known as the Avraham Bronstein pharmacy.

[Page 203]

Moshe Forman tells us that Levental seldom went to the prayer services. Meir Boim once mentioned it and Levental replied him with a smile: “Don't worry, Meir. There will be a generation that will come to my grave and say, 'Old righteous man, get up!” Moshe Forman also talks about the reason Levental left town. When Yaakov-Shimon Koifman died, his body was brought to Yedinitz, and the casket was put in Levental's pharmacy. The Chevra Kadisha did not hurry to prepare the burial since they thought, as was the custom, that the plot was expensive. The Chevra Kadisha said that when it came to Levental, they would charge even more. Levental decided he didn't want the Chevra Kadisha to enjoy such an event.

The pharmacists Avraham Bronstein and his son-in-law Moshe Voskovoynik took over the store in the nice building with the wide steps and acacias and lilacs on both sides. The building sparkled with its cleanliness. They became true citizens, generous and devoted Zionists. In due time, the family opened another pharmacy in the house of Perl and Asher Goldenberg.

The Soviets nationalized both pharmacies. Moshe Voskovoynik was exiled to Tashkent, where he spent the war years. After the war, he came back with his family to Czernowitz, but moved later to Bucharest. He died there in 1953.

In addition to the pharmacies, there were in Yedinitz “druggists.” They were Yeshaya Tolpolar, Shimon Shor, Yechiel Nemitchinitser, Yidel Galperin, Boris Gendelman and Avraham Hayot. The latter was also an assistant surgeon.

Transport

There were Jewish wagon drivers who transported people to the train station (earlier it was to Dondushan and later to Radu-Mare stations). They also took people to the nearby villages: Brichany, Lipcani, Secureni, Britcheva, Rishkan. Sometimes even to Hotin or Beltz. The passengers were called “Porshoin.” Some of the well-known wagon drivers were Haim Reuven, Yankel, Zalman. Some had the surname Feitontchik.

Suddenly, the first automobile appeared, introduced by Yossel Brotzky and Pinie Shofar.

|

|

Standing (from right, bottom to top): Shimon Shorr (died in Israel), Shimon Shrentsel (died in Czernowitz), Hinda (née Shorr) the wife of Avraham Bronstein (died in Israel) From left, (from bottom to top): Dr. Silberman (died in Kishinev), Moshe Voskovoynik (died in Bucharest), Leah Galperin (in Israel), next to her the girl Zippora, Zvia Voskovoynik (in Israel), in her arms the child Yaakov (died on the front) |

[Page 204]

The second and third automobiles came and changed everything. In the first few days, the automobiles would be driven, for a few pennies, through town to Patchova street. The automobiles were like broken vessels. They would stall in the middle of the street as if it were a station.

There were also trucks which transported goods from larger centers, I.e. Czernowitz, Iassi, Odessa. The drivers were responsible for the goods and had to bring them in good shape.

[Page 205]

It happened that the drivers and the merchants had to go to the Beit Din (religious court) to settle a dispute. If something was missing or was damaged, the Dayan (judge) usually followed the “half” rule. The driver had to pay for half of the damage. This was a business in which it was useful to “lose a package.”

Credit Institutions and Banks

Before WWI there was a Cooperative Fund for mutual help. It was located in the house of Meir Boim. The people involved were: Shmuel Vinesheker, Avraham Milgrom, B.Z. Timan, Israel Kormonsky, Meir Blank. Between the two wars, there was the Savings and Loan Fund, also called Ezra (help). Its chairman was Shmuel Ludmir, the bookkeeper and assistant treasurer was Diamant. There were also private or business funds, interest free. They provided small loans to be repaid in installments. From such loans, the Commercial Bank of Yedinitz was established by Israel Rosental, Yehoshua Kolker and others. It soon disappeared. Another local bank, the Credit Bank of Yedinitz, lasted longer. It was founded by Alter Fuchs, Motel Boimlshteyn, Leib Helfgot and others.

Later, a branch of the Bank of Bessarabia, from Kishinev, was opened. Moshe Shteinvartz was its director. This was a solid institution, to be used for honest business. Shteinvartz continued to run the bank even under the Soviets.

There were also private money lenders. They charged gentiles up to 10% interest per month. Jews only paid 3-4% per month. There were also usurers who extended credit with weekly repayments adding interest (in advance). The banks also charged 2-3% interest.

Other Occupations

[Page 206]

[Page 207]

|

|

Oil painting from José Landau, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

[Page 208]

- Synagogue sextons

- screamers

- carriers

- wig makers

- coal providers

- chimney sweeps

- dog catchers - mainly gentiles

- servers

- matchmakers

- middlemen

Industry and Express Trading

There was no big industry in Yedinitz. Still, there were hundreds of people who made a living working in various workshops. The first oil production plant (oil made from sunflower seeds) was founded by Meir the Redhead. It failed. Then, this business line was continued by Aharon Premislow. It did succeed. His oil (later, water was filtered through it) was distributed to distant locations. Over time, three more plants were established by Baruch Akerboim, David Lenkovitzer and his son-in-law Yosef Teiberg, and Mordechai Shteinvartz and his son. These plants also sold what was left after the oil was pressed. The residue was used to feed animals.

Another important industry branch was the production of soap. It belonged to Meir Rosenberg (Burtch) and his sons (his sons are now in Colombia, South America, where they still manufacture soap). The workers were mostly gentiles. The work was hard and dirty, and the wages were low. Many workers spent their salaries on liquor. Their wives used to beg the owners to give them the wages and not to their husbands.

In addition, there was the mechanical mill of Yosef Shpeyer. He built an electric station which produced electricity for the houses and the streets. Electrical power was used sparingly. People tried to save on electricity by using low wattage bulbs. At the end of the 1930s, outlets were introduced for radio appliances.

[Page 209]

Straw making, wool producing. Yosef Gershuny made noodles. Yoel Liberman (Zukernik) made candies.

Did we forget anything? It seems, not. We earlier mentioned Express trading - it means expediting goods from Yedinitz to the big world. We also mentioned oil and soap.

In Yedinitz there were Jews who dealt in animals. The sugar producer, Osipovitch from Ripishten, used the leftover production of beets for his sugar plant. The well-known among the cattle dealers were Yitzhak Mayansky, Leibush Lerner, Meiler and others. They were nicknamed in town as “the butchers.” They even exported animals to Eretz Israel.

Those who accompanied the animals sometimes found a route for illegal immigration. Those who accompanied the animals on the ships, even gentiles, stayed for a few weeks or even several months. The gentiles would send regards from the Jewish land - Palestine (this was the story). They even changed the expression “Jews to Palestine” to “Christians to Palestine.”

There were Jews who traded in pigs. They exported them abroad. They were called “the piggies.” The most important among them was Alter (Yekls) Bronstein.

|

|

From right: Aharon Garfinkel – representative of Singer From left: Mara, the sewing instructor (early 1930s) |

[Page 210]

His tragic end is described in another section of the book (an article by I. Magen).

In town there were also traders in furs, raw silk, leather, lamb pelts. They used to buy from the farmers and send the goods to large centers and even abroad. There were also dog catchers in town who used to sell them to kennels.

Free Professions

Let us list immediately: doctors, pharmacists, lawyers, accountants, clerks, Dayanim (judges), rabbis, cantors, circumcisers, scribes, and other clergy. They are mentioned in various articles in the book. There were some municipal clerks who were Jewish. There were none among the government clerks. Most of the free professionals mainly came from other towns. The first academics who had grown up in town appeared in the 1930s. Their parents worked hard to provide them with a higher education.

Closing Observation

We know that the review of the Jewish occupations in town is short. It does not pretend to be complete.

[Page 211]

Perhaps we were excessive in one area and deficient in another. However, a good description of the socio-economic situation of 6000 Jews in Yedinitz was given. It is probably quite similar to the situation of other Jewish towns in Bessarabia.

The above-mentioned structure began to deteriorate even before the great national catastrophe. One economic disaster followed another. In the 1930s the impoverishment of the merchants, clerks, and artisans was felt among the Jews. The first sign – emigration to larger towns and abroad. The majority went to South America and the rest to Eretz Israel (not all were pioneers).

Even if the terrible catastrophe had not happened, the Jewish shtetl would have changed anyway in the socio-economic structure.

Today, there are in Yedinitz a few hundred Jews. Most of them work in Soviet institutions - cooperative and commercial work. That is, they are all traditional Jewish economic endeavors.

Translator's footnote:

By Shmuel Kormansky

Translated from the Yiddish by Ala Gamulka

| This article is dedicated to the Roitman grandparents we never knew. The courage and determination that they showed in migrating to the United States, the last in 1930, has borne fruit: Nine grandchildren (Elliot, Jane, Arlene, Dennis, Sherry, Nathan, Allan, Howard, and Phillip), and numerous other descendants all over the country. Whatever the swirling emotions and considerations that drove them from Yedinitz, we are grateful for the lives they gave us. |

| We must emphasize from the beginning that there were very few Jews who were actually agricultural workers in Yedinitz. Those who did work the land with their hands were the vegetable growers Berl Duvidl (near the Pansky River, the Wealthy People's River) and Mordechai David (near the Seminary River). “River” was not really a river, but a pool of standing water. Among other workers, we should also mention the Jewish tobacco growers who cultivated many disatins of land. |

Among the lessees (they were referred to as tenants) there were many who were first-class experts in all branches of agriculture prevalent in those days. I will mention my father Naftali Tabaner (Kormansky), a born farmer; also, Shmuel Loibman (Drutzer), who was an expert. Many people turned to him with questions about agriculture and natural disasters.

Many of the Jewish agricultural experts were managers working on estates owned by wealthy people. They were Avraham Milgrom (worked for Kochanski in Glinoye), David Gardadtzki, and others.

Among the land lessees prior to WWI, I wish to mention my father Naftali Tabaner, Nissan Vaisman and his partner Itzik Millman (Turk), and Shabtai Roitman. The latter was a partner for some time of Naftali Tabaner. There were also partnerships between Meir Boim and Shmuel Oynshenker, Yaakov Roitman, Yaakov Lerner (Rotunder), Koppel Shteinik and his son Israel, Akiva Fradis and his son Shmuel, Azriel Eidelman, Zalman Pitshoner, David Loibman and his brother-in-law Itamar Muchnik, and Yekutiel Kormansky.

[Page 212]

They were the “old generation” of land workers. Their sons became the “new generation” during the Romanian conquest. Those who stood out among them were my brother Israel Kormansky and I, the author of this article, Shmuel Fradis, Israel Shteinik, Leibush Lerner, Avraham Gendelman, Israel Rosenthal, Moshe Lerner, the partners Neta Shor and Asher Goldberg and others.

We will now mention the location of the leased lands. Near the town: the villages Glinoye (Linoye), Potche, Ordinetch, Korzsheutz, Porkeve, Terebne, Zobritchen, etc. Others were further away. The leased and farmed areas covered thousands of disatins. Thousands of labourers were employed there. At some point, the author of this article worked 500 disatins (over 6000 dunams) and employed hundreds of labourers during the busy seasons of harvest.

The harvests were sold in big cities in the country (earlier it was Russia and later became Romania). The lessees were associated with exporters and middle agencies who provided support at the expense of the providers. This way, it was possible to prepay the leasing costs to the owners and to subsidize work during harvest time.

Some lessees also had forests, where trees were cut and made into boards and beams to produce barrels, wagons and wheels, fences, used for construction or for heating purposes. There were no mechanical sawmills in town. Laborers would cut the wood manually (they were mainly Katzaps) with long saws. Among the land lessees I would like to mention Naftali Kormansky, Shmuel Ludmir, Pinchas Parnas and his son Yaakov and others. The forest business provided a good income to those in it.

Tel Aviv

[Page 197]

by Aharon Chachmovitch

Translated from the Hebrew by Mary Jane Shubow & Ala Gamulka

| Aharon Chachmovitch, was a farmer in Yedinitz and grew tobacco for many years. He is now in Israel with his son Yosef, who is one of the founders of Kibbutz Chanita. Ephraim Shwartzman-Sharon recorded his words. |

The wealthy landowner Kuznitzov was the first to introduce the tobacco industry to Yedinitz, which employed many peasants from the villages in the surrounding area. Tobacco fields stretched over hundreds of DISATINS.[1]

Among the Jews, Rav Moshe Lemchinsky was the first to grow tobacco. He and his wife came from the Ukrainian town of Lemchinitz. They brought tobacco seeds with them. Rav Moshe's wife helped a lot in the work. She had learned the profession while still at home with her parents. They arrived in Yedinitz in the 1880s.

The next Jew to work in this branch was Rav Yitzchak Reuven Vasilis, and those who followed, were Yechiel Gandelman, Yekutiel Chanes Rosenberg, Zalman Leib Dimant, Yechezkiel Tatar, Hirsh Berl Shayfs, Walwil Shvartzman, the three brothers Yakov, Aharon and Moshe-Yeshayhu Chachmovitch and others.

The Jewish tobacco growers employed Jewish workers for the main work of the business - planting and drying.

[Page 198]

To dry the leaves, they would thread them through long wires (known as “SHWARAS”), where they spaced them out and hung them in large structures specifically built for this purpose.

In the beginning, the tobacco crop suffered at the hands of the heavens and from troubles that came from human hands as well. The Katzaps and the Gypsies would cut down the plants and destroy the saplings in the fields. After a lengthy scouting and tracking process, they were caught and handed over to the authorities for imprisonment and expulsion from the town.

The profitability of growing tobacco was higher than other branches of agriculture. However, in times of drought, there was not even enough income to pay for the workers' salary.

In 1917, when Bessarabia was conquered by the Romanians, conditions worsened for the tobacco growers. The Romanians initiated an agrarian reform. They divided the owners' land among the farmers. Even Jews who could prove were farmers received plots of land (a plot of 3 hectares was known as a “lot”). At the same time, the Romanian authorities published an order that designated tobacco growing and its commerce as a government monopoly. Therefore, the Jews of Bessarabia were prevented from growing tobacco and doing anything associated with it, such as drying, cutting, and curing it for sale. And after that, the growing of tobacco came to an end in Yedinitz.

Translator's footnote:

By Mordechai Reicher

Translated from the Yiddish by Ala Gamulka

| As in other Jewish communities, there were in Yedinitz various “societies,” committees, and public institutions. Their main purpose was to assist the poor residents, and there were many such people in their time of need. These were charitable institutions led by volunteers; those who were active in them, as well as the contributors. The names of these societies and committees had common names written all in Hebrew and were well accepted in the Jewish communities: “Help for the Poor,” “Charitable Benevolence,” “Help for Poor Brides,” “Help for the Sick” (not “visiting the sick” as seen in other places), “Help for Passover Food,” “Clothing for the Needy,” “Secret Giving,” etc. These committees were for the most part unelected and those people active in them saw their work as a holy task. |

It is important to mention the main public figures in these organizations, such as David Serebrenik, Reuven-Peretz Grozman, Yaakov Schwartzman, Yehoshua Kolker, Hirsh Rosenberg (Kasils'), and others. The duality in deed and purpose was not unusual. They were often the same people who volunteered in several organizations. Even the collection of funds and donations was similar in all chapters. The wealthier people gave specific sums of money every week or every month. The sums were not necessarily large. On the eve of Yom Kippur every group placed a “bowl,” among other “bowls,” on the table at the doorway of the synagogue. In addition, every group sent a representative to all celebrations, family gatherings, weddings, etc., to collect funds from the participants. No opportunity was missed to help grow the finances of the group.

The committees would meet at specific times regularly to discuss problems, budgets, and needs.

We shall now briefly review the societies and committees that were active in town in philanthropy and assistance.

Help for the Poor

This was one of the most important and well-known associations in town. Its primary purpose was to give assistance, usually financial, to the needy. Sometimes this aid was on a regular basis - weekly or monthly. At other times, as a onetime allowance. The committee also looked after the hidden needy when suddenly fate caught them. They were people who lost their business and needed support but were too proud to ask for help. When the committee heard about such cases it made certain to give help in secret, so others would not know.

By the way, there was also in town a special committee to assist the hidden needy. It was called the “Secret Giving.”

[Page 214]

The “Help for the Poor” committee also looked after the “Help for Passover Food,” which looked after the needy at Passover time (providing Matzos, wine, potatoes, eggs, and other Passover items).

The committee of “Help for Poor Brides” aided young women who were ready to get married. As their parents did not have the means to provide a dowery, not even a minimal one as was the custom in those days, assistance was given to prepare the wedding, start a home, and for first necessities.

In town there were several funds for “Charitable Benevolence” in the synagogues, within certain professions, etc. These funds provided their members with loans without interest or at a very low rate. They were called “Little Banks.” Every member gave a specific sum when he joined. When it was their turn to take a loan, the member could repay it in weekly payments. At the head of several “Little Banks” stood David Serebrenik (chairman), Yehoshua Kolker (treasurer), Yankel Forman (Baruch-Tem's), and others. Such a “Little Bank” was also established by artisans headed at times by Yankel (Haim-Aron's) Wasserman, Haim-Eli Weissman, Mordechai Sheindelman, Noah Sandler, Michel Krik, and others.

Old People's Home

Until the end of the 1930s there was no appropriate institution for caring for the needy, single elderly. For various reasons, at the end of the 1930s the high school was closed. It had used as the “People's Building.” At that time, Moshe, the son of Shmuel Vineshenker came for a visit from America and donated a considerable sum to commemorate his late father. The family of Avraham Bronstein as well as Shmuel Shpeyer joined him for this cause. The donations collected were large enough to buy the building and to furnish it with the necessities to decently accommodate a few dozen elderly people.

[Page 215]

The women's committee did the actual work of providing the necessities and maintenance. It was headed by Hava Shpeyer and the secretary was Liza Galperin. Other women assisted them such as Tzeitel Fradis, Hana Axelrod, Henya Forman, and others.

When the Holocaust reached town, the killers touched even the Old People's home. Haike Shpeyer came to the institution by chance as the killers breached the building. They ordered the old people to leave immediately. “No one must dare stay!” they announced with cruelty. It was a shattering picture to see the several dozen miserable elderly men and women, desperate and helpless, leave the building. Among them were the sick, the weak, and the stunned. They had small packages under their arms and were abandoned to hunger, lack of needed materials, and death. This nightmarish picture accompanies still Haike Shpeyer and she cannot free herself from it even though thirty years have passed.

Hostel for the Poor

Another social institution, a little unusual, was the “Hostel for the Poor.” Its purpose was to give poor passersby a shelter and a place to sleep.

The house was small, poor, and rickety, and it stood in a remote part of town among narrow lanes. The furniture inside was simple: a table, a bench, and a bed. The inner and outer look of this “hotel” made a very sad impression on anyone passing by and entering inside.

It must be understood that the house was built at the end of the previous century as part of the will of Meir Grinberg. He was known in town as “Meir the Redhead.”

[Page 216]

Pearl Shor-Goldberg, granddaughter of Meir the Redhead, discusses the reasons for establishing it and looking after the “Hostel for the Poor”:

“Grandfather Meir was well known for looking after the poor. When he encountered a person alone on the eve of Passover in the synagogue, he decided to create the “Hostel for the Poor” in a building in his courtyard. His neighbours opposed it because it was the period in which cholera was rampant in town. The neighbours feared that infected people would be housed there. Before he died, my grandfather left a will with my mother, Osnat. He instructed that such a building be dedicated with all that it entails. My mother fulfilled her father's wishes. She somehow obtained the funds for purchasing the house, to furnish it, and took care of it all her life. She even sewed curtains and always tried to keep the house clean and orderly. She made sure the house looked right, and that there was a pleasant atmosphere for those who came.”

How was the house maintained after the death of Osnat, Meir the Redhead's daughter? She was the loyal caretaker. This, is difficult to determine. We assume a committee called “The House for the Poor Committee” did it with the helped of regular and onetime donations. The residents in town were generous. We must note that every tenant paid a few pennies towards the cost of the night stay. (For more information, please read the article in Yiddish by Menashe Halperin on page 215.)

|

|

1. Chayka Parikmacherin 2. Katz-Ronberg 3, 4. ----- 5. Sarah Fried 6a. Dora Bitner 7. ------ 8. Chaya Eisenberg 9. ---- 10. Yehudis Riesman 11. Zlata Zonenschein 12. Fanya Kormansky 13. Lisa Galperin 14. Chana Axelrod 15. ------ 16. Chaya Mayansky 17. ---- 18. Zvia Fishman 19. Manya Gerstein 20. Feiga Monstein |

In town there were also a ladies' committees for philanthropic help. One committee worked to collect donations for the Old People's Home. The women received from this committee or other funds for the two Talmud Torahs in town. One was modern and located in the Shaarei Zion Synagogue; the other, more conservative, was in the Upper Marketplace. The Ladies' committee gave gifts to the students of the Talmud Torah, most of whom came from poor homes.

There was also the “Rebbetzin's committee” composed by the Rebbetzin herself, the wife of Rabbi Michael Burstein, ZL.” She called her committee “Clothing for the unclad.” All year round there were young women recruited by the Rebbetzin who went from door to door to collect small donations. With the funds, the Rebbetzin bought cloth at cost from the merchants. Such material was called yellow linen (in Israel is called Arabic cloth). These young women sewed shirts and underwear and the Rebbetzin would distribute them among the poor folks twice a year, on the Eve of Passover and the Eve of Rosh Hashanah.

Loaf of Bread

The role of this institution was to distribute food to the suddenly needy. They did this in secret. They delivered challah, fish, and meat for Shabbat to celebrate the day properly. The ladies knew who needed help. In the middle of the week, they ordered what they needed to distribute from wealthy homes. On Friday afternoon, they collected the donations and the food and brought them to those in need. This was done after dark to not embarrass them.

[Page 218]

Heading the “Loaf of Bread” committee were Adel Gendelman (the Coopersmith), Sarah, wife of Zosia Melamed, and others.

The committee also helped needy pregnant women by giving them special items: chicken soup, sugar, butter, pharmacy products, and even linens for the mother and the baby.

AZE

This institution was registered and functioned in the medical field with help to the needy. The assistance given had many sides: the direct medical help was provided by Dr. Zilberman, Dr. Grinberg, Dr. Shoot, and others. It was offered in the special reception room in the home of the Fradis family. In addition, there were special visits to the doctor's office. Hospital admissions were also included. It must be noted that the doctor's' donated their services. There were no costs. Among the women active in this institution, the following must be mentioned: Henya Shteingvurtz, Ita Bronstein, Mindel Dobrov, Zunis, Falik, Sosya Shitz, Tzeitel Fradis (chairperson), Hannah Axelrod (secretary), and others.

Of course, we did not invent the topic of social assistance within the community of a Jewish town in the Diaspora and Jewish solidarity in the context of the reality of exile. All the other committees functioned similarly to what was described above.

[Pages 215-216]

By Menashe Halperin

Translated from the Yiddish by Ala Gamulka

Old people's homes were a rare phenomenon. The larger towns had them but were not often built by donors in the smaller towns such as ours.

Everywhere there were houses for the needy: a poor, a filthy place for an overnight stay or even used as a permanent residence. It was intended for the disabled, orphaned, mentally deficient, half-mad women, and low-class losers. There was no regular maintenance in these houses for the poor. Their residents were beggars.

Kind-hearted and charitable women used to bring food, old clothes, and shoes.

In such houses for the poor, there were some deaf-mute young women who never knew their parents. No one had ever looked after them. They grew up in these houses and their mothers became more independent and better situated. A mother holding a young child received for the child or for herself some clothes and a way to live in a decent place.

This is how rough, young men were made to marry such a young woman. This meant that they were both helped.

(Excerpt from the book about the Jewish shtetl in southern Ukraine and Bessarabia, end of the 19th century - “Parchments,” by Menashe Halperin. His biographical notes.)

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Edineţ, Moldova

Edineţ, Moldova

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Aug 2022 by LA