[Page 78]

My shtetl

Here it is, a shtetl so tiny that it doesn't even exist on the map. Even if we discover that it lies somewhere close to the border of Polessia and Volyn and even if we pinpoint the spot where it is situated, next to the river Horyn, it will be difficult to locate its precise position. Yet it is etched in the hearts of those who were born and lived there.

In this shtetl there seethed a vibrant Jewish life. Every aspect of the Jewish people and every current in Jewish thought was reflected and represented in it. The majority of its Jewish inhabitants were Chassidim, but there were also a few misnagdim[315], and there were Zionists and non-Zionists. HeKhalutz and HeKhalutz HaTzair brought together the majority of the young people in the shtetl, but there were also some who leaned towards other political movements and other philosophies: communists, Bund[316], General Zionists, Revisionists and so on. There were no assimilated Jews in the shtetl.

In all of them there beat a warm Jewish heart, prepared at any time to come to the aid of other members of their community. This readiness to help was revealed especially in times of trouble. Whenever a fire broke out in the shtetl Jewish assistance would be shown towards those who had been burned out of their home.

When, on a snowy winter's day, the water was frozen in the well, all the neighbours would rush to help with the hard labour of drawing the water. When somebody was sick they would look after the welfare of his family. And when families were without food it was a matter of course for help to be forthcoming. There was no municipal authority or government to support the needy, only the spontaneous response of the Jewish heart. That is what sustained all of them.

The little shtetl sent many pioneers to Eretz Israel. They are now scattered throughout the Land. Most of them were in training before they made aliyah to the Land, and even those who did not manage to make aliyah were deeply attached to the idea of rebirth and redemption in the Land. The heart grieves and weeps for all those Jews, children and teenagers, men and women, young and old, whom the enemy hurled into the grave.

May their memory be blessed and may their name endure for ever.

| |

Lea'ke Lopatyn-Cohen

Kiryat Motzkin |

[Page 79]

On the Banks of the Horyn

On the banks of the Horyn lies the shtetl. Steppes and dark forests, above whose horizon there rises a wild splendour and grace. 150 Jewish families live there. Each family has a house of its own, a low wooden house, a small patch of land, a vegetable garden and even a milk cow in the cowshed. They earn their bread by the sweat of their face[317]. They are reared in poverty.

Sometimes a fire breaks out in the shtetl or a disaster happens. When that happens one family stands shoulder to shoulder with its neighbour. The shtetl has not known the bright lights of the city, but neither does it know isolation between one person and another. Life flows slowly here, a life gray and peaceful.

And children grew up in the shtetl, full of innocence and faith. But once they became aware of what was happening beyond the borders of the shtetl the soul was stirred and the imagination captured from afar by the story of the construction of the homeland. The shtetl was narrow, suffocating. They rebelled against their parents.

A rush began to HeKhalutz and Klosova[318], then aliyah to the homeland. For years the shtetl has linked its destiny to the Land. The best of its children are there.

Vysotsk is proud of its pioneer past, to which it remains loyal. It is proud of its children who took part in the fight to defend the Land. The young generation is brought up in their light.

I came here at the end of summer, having had enough disappointments and enough wandering from place to place. I saw large, strong [pioneer] branches reduced to their current shameful condition. On the way here how apprehensive my heart was lest … lest Vysotsk should also disappoint. I found it sound, loyal, a corner of light in the darkness.

When I arrived in the shtetl I was immediately surrounded by a swarm of children, examining the 'strange aunt'. They surrounded me in pioneering naivete: she's 'ours'! Their faces blushed slightly, but as soon as they saw my friendly face they plucked up courage. The ice broke and their lips spoke: Please tell us, let us have a conversation!

We went into the club. A spacious room, tastefully decorated. The group of children sat around me, singing. They love the quiet songs that express themselves slowly and that tell of human feelings. These little ones know how to listen to a song.

Suddenly there is a request: 'Sing us a new song'. I consented. From the very first moment a bond of love was formed between us. It is really so good being with them.

I began bay mayn fenster in dem gorten[319]. They listened intently. They knew the melody, but the story interests them. The story is of the good boy whose flowers, that he had tended and nurtured with a great deal of love, were picked by some naughty children. 'Is it right to pick beautiful flowers which want to live?'

[Page 80]

|

|

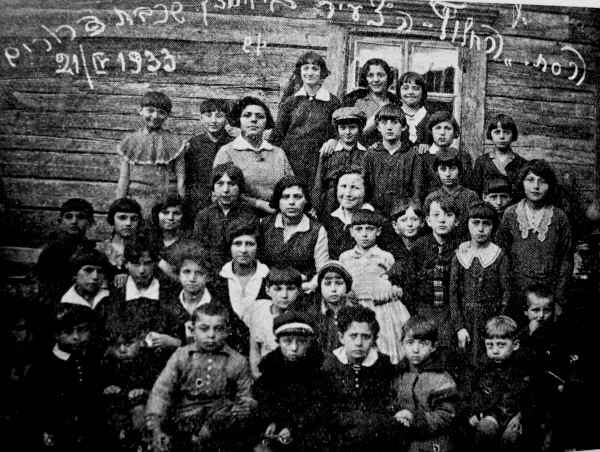

From right to left, top row: Vinner, Mina Zolyar, Rushke Goldberg;

Second row from top: Tzirl Goldberg, Mirl Gottlieb, A. Shnayder, Sara Nafkhan, Sara Durchyn, Risya Shnayder, Kaviar

Third row down: Feygl Berman, Malka Sher, Brakha Feldman;

Fourth row down: Ronya Shlyapak, Gitl Furman, Chana Vaks, Tzipora Shuster, Rivka Fialkov, Mindl Sheynman, Elka Shnayder, Chaya Zolyar, Furman;

Fifth row down: Esther Shlyapek, Sara Lieberman, Kaviar, Mindl Sheynbeyn, Khasya Borovyk, Feygl Rykhotsky,…Lakhmanchuk; bottom row: …, Rabin, …, Brakha Vinnik, Asher Aaron Sheynbeyn, Aharon-Shmuel and Feygl Fialkov,…Kortach

|

A conversation develops. They remember trees chopped down in the Land, find what is in common between the flower yearning for the sun, thirsting for dew, and the Jewish pioneer asking for a rooted life, the life of nature. We turn to tragic events in the Land, and sorrow hovers over their faces. They are sad, very sad.

I read them the story 'The tree that was chopped down'. Hearing about the tender oak, uprooted and tossed on to the ground, their eyes are filled with tears. It is hard to see them in their distress.

In my heart I pondered. How terrible it was that wicked deeds deprive even our little children of their innocence and the joy of life. I tried to console them. I went on to tell them that the pioneer in the Land will not despair of building afresh, will plant and sow until hatred between man and man will cease.

The young ones decided to call their group by the name 'The Planters'. How I loved them when I saw their sadness and their enthusiasm. I firmly believed that they would indeed be young planters in the homeland.

[Page 81]

|

|

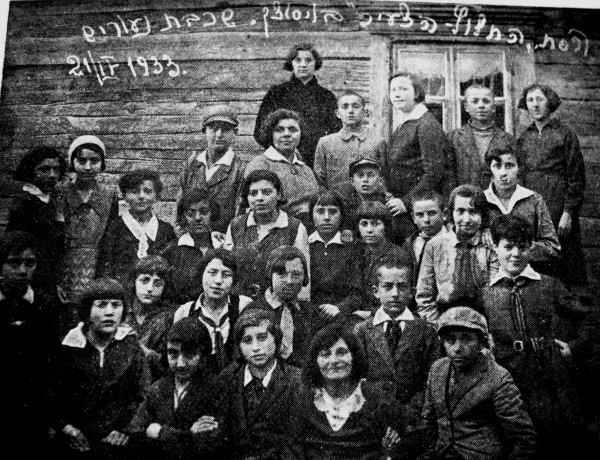

From right to left, top row (standing): Chava Nafkhan, Eliahu Goldberg, Tzipora Shuster, Yedudl Furman, Mina Zolyar, Sara Durchyn, Shlomo Furman;

Second row from top: Gitl Sheynman, Esther Furman, Itzhok Shnayder, Chaim Sher, Brakha Feldman, Dvusya Shtoper, Rivka Fialkov, Freydl Furman, Lifshe Borovyk, Breyndl Lopata, Nishke Lopata;

Second row from bottom: Pesl Shnayder, Itzhok Lopata, Rakhel Khaznchuk, Feygl Mayzl, Sara Khaznchuk, Malka Lopata, Teybl Fialkov;

Bottom row: Yaakov Vinnik, Dina Berman, Kh. Pesl Lieberman, Esther Shuster

|

On the occasion of my aliyah

Sometimes I wonder: can it really be true that no Jewish community exists in Vysotsk? That community which I knew in its joys and sorrows, where private joy was a joy shared by everyone and where they all felt the pain of an individual sorrow, that community where devotion and love reigned and where manual labour was how the majority of the inhabitants of the shtetl earned their living.

I have beautiful memories of the shtetl where I was born and grew up. I stayed there until the age of 17, when I made aliyah to Eretz Israel. It was towards this aim that my most beautiful dreams had already been embroidered in the Tarbut school, where we were taught by our teacher Yaffa Geklman. During lessons on the Torah and at every other opportunity she would talk to us about Eretz Israel. In summer when we went for walks outside the town which we organised on behalf of the school she would read from newspapers from the Land. We would sit on the grass and listen to her, quivering with excitement, and dream of the Land.

We grew up with the love of parents and family. We also knew how to respect our parents and other adults and to love the People of Israel. I remember, while I was still at school, our class organised a scout group. Our motto was 'A healthy soul in a healthy body'. Our leader was Itzhak Ryzhy of blessed memory.

[Page 82]

After that, from the scout group, we organised ourselves into a Kadima[320] group. we were then also joined by the young men who taught privately and in the Talmud Torah. We were a group of young men and women, and our aim was to make ourselves ready for life in Eretz Israel.

From Kadima we moved to HeKhalutz HaTzair. In HeKhalutz HaTzair there was a life seething with excitement. It grew and grew. The parents were against their children visiting the branch because they knew that this would lead to aliyah to the Land, something that at that time they were against. But slowly, over time, they began to get used to the situation and occasionally, without our knowledge, they would creep up in secret to see what was going on in the branch. I remember once when we came out of the branch clubhouse at a fairly late hour I saw my mother and Chava Vaks strolling past the club. I ask: 'Mother, what's the matter?' 'Nothing', she answers, 'we came to see what you get up to in the branch'.

Our mothers knew how to find joy in another person's joy. Any letter that was received from the Land would pass through almost the entire shtetl. I remember when my sister Rivke got married and wrote that she was living in Nes-Tziyona and the wedding was at Etil Vaks's place in Rehovot the women began to ask about the distance between the two settlements. Mother answered them 'It's like from Vysotsk to Brodetz'. So she told me laughing. When I came to the Land and would walk on foot from Nes-Tziyona to Rehovot I thought to myself what a splendid sense of direction my mother had had!

In 1932 I made aliyah to the Land. On the night before my travel many of my girl friends came to bid farewell. There, among the preparations, I see Mother sitting with tears in her eyes: 'Mother, what's the matter?' She answers: 'Sarali, you are only 17 and I haven't had enough time to look at you'… And she burst out crying. I kissed her and calmed her down: 'Mother, you will all come to the Land and you will still be able to see me for many years.' To that Mother answered: 'Were it not for that hope I would not let you travel'.

The next day the whole shtetl came to accompany me to the train. I took my leave of all of them. Father stood aside. I went up to him and said to him: 'Father, we have to say goodbye!' He burst into tears. This was the first time I had seen my father cry. Through his tears he says to me: 'Sarali my daughter, will I manage to see you again? I am unable to give you anything other than my blessings which will accompany you always. Always endeavour to do what is good and honest and remember that you have left us here. Write at least one letter every week'.

Yes, Father, I sent letters every week. I always hoped to see you again, the shtetl and its people that I loved so much, but I was not able to. The end came down on the community of Vysotsk, and from it only a few survived.

Our heart grieves for those who were destroyed by the hand of the murderer. The heart is bitter with pain.

| |

Sara Petrukh-Moravnyk

Netanya |

[Page 83]

|

|

| The HeKhalutz branch in 1933

|

This is how they were

The little shtetl of Vysotsk, which had the appearance of a village, rests on a hillock near the border between the provinces of Volyn and Pinsk, between the shtetls Dombrovitza and Stolin. It is about 8 kilometres from the shtetl to the nearest railway station, Udrytsk. Nearby runs the river Horyn, the waters of which pour out over its banks in the months of spring. With the thawing of the snows the water covers wide areas of low land, creating swamps around the shtetl. At this time the shtetl would remain cut off from all other human settlement; there was no way out and no way in.

Vysotsk is considered to be an ancient shtetl. According to the stories of the old people it dates back several hundred years; indeed some ancient gravestones remaining in its cemetery from hundreds of years back are evidence of that. There is no community journal here and there probably never has been. Vysotsk was influenced by Volhynian Dombrovitza on the one hand and by Chassidic Stolin on the other hand (the latter is regarded as belonging to White Russia). For generations, until the Polish occupation in the year 1920, its links were with these shtetls.

No important events took place in it. The life of the thousand Jews in it was quiet and peaceful. There were hardly any troublemakers, there was hardly any strife in the shtetl. Everyone was busy with his work and sat in his shop, taking care of the livelihood of his house. This was not easy and was only achieved with much scrimping and scraping. They did not aspire to great things and did not acquire wealth. Peaceful relations prevailed among the Jews themselves and between them and the non-Jews in the village and those in the neighbourhood.

[Page 84]

The Jews of Vysotsk were pious. Everyday life continued throughout the course of the week, but when the Sabbath approached the shtetl took on a different form. Every Jew went to the public baths, removing everything relating to everyday life. The shops closed on time, and through the windows of every house Sabbath candles in polished candlesticks shone in a shining bright light. The children ran around in their Sabbath clothes. Young and old rushed to the synagogue to welcome the Sabbath, Queen of the Heavens. In the synagogue they prayed with Chassidic enthusiasm, and there was a special festive feeling throughout the whole of this Jewish shtetl.

While they were still very young the children started to study in the cheyder. The cheyder was of the type usual in the Jewish shtetls. In a small narrow room in the melamed's[321] house they sat around a tightly packed table, listening to the teaching and studying alef beys[322] and Hebrew with the teacher. Every Thursday a kind of examination took place. In such conditions great scholars could not be expected from the cheyder; education remained at a low level.

During the First World War (in the year 1915) the local activist Chaim Ayznberg was stirred into action and began to concern himself with the education of the young generation in the shtetl. He collected a number of children without education whose parents were unable to pay fees to the melamdim, rented a house and founded a school for them. Bila Ratner and Lykhtnfeld joined Ayznberg as teachers. The lessons – Hebrew and general subjects – began in the school. There were those in the shtetl who were dissatisfied with the method of education and with the school in general. This was only natural. But Ayznberg did not back down and continued with his important project. After the Balfour Declaration[323] was published and the winds of freedom were blowing in Russia activists were found who helped Ayznberg put the school on a sure foundation and attract children and parents and win over public opinion. From it there emerged a national generation on whose lips the Hebrew language was alive. From their ranks came those who were subsequently educated in training kibbutzim and made aliyah to the Land.

Among teachers at the school we have to mention Kant, Shokhet and Ternopolsky and among the activists Zeydil Lopatyn. All of these, with Chaim Ayznberg at the head, formed a mass Zionist movement in the school. Zeydil Lopatyn, a former pupil of the cheyder who came from a family of fishermen in the shtetl, was one of the first to devote himself to the Zionist movement with all his energy. He loved the theatre with all his heart and organised an amateur group in the shtetl which excelled in its performances. They would dedicate all the income to the cause of Keren Kayemet le'Israel[324] or similar institutions. He had excellent speaking ability. He would stand in front of a large public without flinching, and his words stirred the public to Zionist activity. For many years he worked loyally until he moved to Luninetz. When he was there he also did not sit idly, continuing the Zionist activity for which he was renowned in all the surrounding area.

And we should remember Moyshe Levin, grandson of the rebbe Moshke of blessed memory and son of Leybush the butcher. He had also studied in the cheyder. When he reached the age of 11 he was sent by his father to the yeshiva[325] in Zhytomir, where his older brothers had already studied. He studied there until the

[Page 85]

war broke out in 1914. While still in the yeshiva he began to disapprove of the differences between social classes. He was a boy of 16 when he ceased his studies and became interested in the revolutionary movement.

Towards the end of the First World War Moyshe returned to Vysotsk. Gangs and various groups with weapons in their hands would pounce on wayfarers and on settlements and small shtetls. A self-defence group was organised then in Vysotsk, and Moyshe Levin took an active part defending the shtetl. During the period of Polish rule Levin began to be active in the pioneer movement. He went to a training kibbutz, but not much time elapsed before he left the Zionist movement and turned to communism. Despite his alienation from religion people in the shtetl loved him for his honesty and sincerity. More than once the local rov invited him for a conversation. Moyshe suffered more than a little hardship; he was persecuted and captured and sat in prison. When in the last war the Red Army entered Vysotsk he was appointed governor of the region. According to all accounts he also escaped the Nazis, surviving in Vysotsk. In the end he and his wife went to Russia.[326]

Sons of Vysotsk knew how to give the Goys a beating when necessary. So, for instance, at the time of the revolution, when the army was celebrating the victory of the revolution, the priest with people of his retinue, carrying torches and icons, came to the shtetl in a procession. The Jews joined them with the Sefer Torah[327]. Together they danced and celebrated the liberation which wasn't 'theirs' [i.e. neither the priest's nor the Jews']. The self-defence group that existed in the shtetl and its general shtab[328] were based in the town prayer house. They were of benefit to the residents on more than one occasion. All the instructions came from the synagogue, and when there was a pogrom they knew how to beat off an attack. The main commander of the selfdefence was Shymon from Bila, a village near Vysotsk, a boy of brave heart, armed from top to toe. He would be the first to appear in all the dangerous places. His deputies, Lykhtnfeld and Sheynman, were also courageous. Mobile guards were nominated from among the members of the self-defence. They inspected all the strategic points.

An event occurred affecting the rich Lykhtnfeld family. Petlyura's[329] people entered and stole all their possessions. The self-defence galloped to the scene, captured the head of the gang, brought him to the government house and removed his weapon from him. Meanwhile Lykhtnfeld's father arrived. In front of everyone he slapped his son's face and sent the commander of the gang back in the wagon in style.

Women of Vysotsk also knew how to stand their ground. Dvoyre Itziks was known to be a smart woman. She smashed the head of one ruffian with a block of wood when he attacked her. In the early days of Polish rule the young men went off to the field to look after the cows. A group of ruffians led by Bolek Belkovych came up to them. All the young people of the shtetl ran away and hid, but some were caught and took blows (including me). Later, when I returned to the shtetl, I averted my eyes from the sight of the pogrom inflicted by the ruffians. It was only with difficulty that I managed to find the majority of the residents of the shtetl who were hiding in the cemetery.

[Page 86]

I remember the incident that happened at that time in one of the houses where they were sitting shiva[330] for the deceased and had come to pray in a minyan[331]. In rushed the robbers, taking all the men – 18 in all – and placing them in the middle of the market place in order to shoot them. After prolonged negotiations the people were ransomed in hard cash, paid in full, in accordance with the robbers' demands. Moyshe Ayznberg was murdered while he was standing in morning prayer, the talis and tefilin on his head. The ruffians demanded money from his family and received what they asked for. When Ayznberg tried to escape through the window they killed him on the spot. At that time the Poles were in the process of taking control. Their administration established peace in the neighbourhood.

There were no proper organisations offering help and assistance in our shtetl, but human feeling and mutual understanding between one person and another were alive and well. I remember how Henya Sheyndles would go out into the town on Fridays and eve of holidays whatever the weather, in rain and snow, to collect from anyone who would give food and money for the poor of the shtetl. After her death her place was taken by Minke, whose heart beat with the desire to help people in need.

This was not the only sort of help available in Vysotsk. There was also help in other areas. In the case of illness, when Kopchik or Kalinsky gave instructions to take the sick person to Rovno or Warsaw for treatment, help would always be organised. Khava Lifshes and Feyge-Mirl would go out into the streets to collect money to cover the cost of transporting the sick person. If the money collected was insufficient they would come to Lekhia-Etil (my mother) and obtain an extra contribution from her, and the sick person would be taken in time for the remainder of the treatment. And if a poor visitor or an itinerant preacher came Nisl Meirs would already be on duty, making sure there was somewhere to sleep, that there was a warm meal and also food for the onward journey.

Nisl Meirs also had other responsibilities. Every Sabbath in the early hours he would wander from street to street to remind the public to go to the synagogue to 'chant Psalms'. He had a special song. This is how it went: 'People of Israel, get up and worship God, for this is why you were created'. Nakhum the beadle would already be making sure the prayer house was heated in time. They would gather for prayer and also for a bit of 'politics'. There were no newspapers or radio in the shtetl.

Yet despite that the news flowed. Also on weekdays, between mincha[332] and maariv[333], news from the world and from the shtetl would flow - also facts and opinions and commentary embellished by a good Jewish imagination.

There was no lack of public work in the shtetl even if it was not organised. Everybody would have a special area of responsibility. For instance it was Nisl Borukh's job, whenever Jews were killed by bandits on the roads or in nearby villages, to go out himself, accompanied by a 'Goy' wagon, to where the killing had taken place in order to bring the victim back for a Jewish burial - despite the danger involved in the matter. Borukh Shleymes would not at the time think twice about the distance from his home, nor about whose property had been burned (whether Jewish or 'Goy'); he would immediately grab a bucket and run to where the fire was, to put it out, to save, to help…

This is what the Jews of our shtetl were like…

[Page 87]

People in the shtetl

I am going to tell you about some of the people in the shtetl that I remember. The first of them, Chaim the melamed, was an infant teacher. I remember him when he was already old but still had small children. He was very very poor and a pious person.

The local rov, Yehuda Abelson, a distinguished scholar of the Torah and pious, made his living by selling yeast and Sabbath candles. The shopkeepers of the shtetl were expressly forbidden from selling these products so as to enable the rov to make a living. I also remember that during the first war there was a shortage of bread. They would pass by every eve of Sabbath to collect a little flour for him to bake bread for himself, like all the Jews in the shtetl.

As has already been said, this rov was a distinguished scholar of the Torah and pious, strict by nature. All the Jews of the shtetl were very wary of his wrath. He was also a judge who passed judgment in cases of conflicts between one person and another.

He had three sons. The eldest was called Bonim, an educated man in the end of the nineteenth century meaning of the word. The second, Yehoshua, served as a rov. He was the last rov in the shtetl, taking the place of his father who in his old age moved to the neighbouring shtetl of Plotnitze[334]. The third son, Khezkil, always stayed close to his father's table, sitting over the Torah in the prayer house. I remember I lived near the house of the rov. Whenever the rov's wife travelled away from home I would spend the night in the rov's house, in accordance with his request. I was very attached to the rov, whom I greatly respected.

I remember the bitter and fateful day on which the Petlyura people murdered one of the elders of the shtetl, Reb Moyshe Ayznberg. On that day people of the shtetl escaped from their homes and hid in all sorts of secret places. Then I met the rov in the old cemetery where he was crying like a child. I rushed to see what the situation in the town was like and if it was possible for people to return to their homes. In the evening we all gathered. We brought the rov to spend the night in our house. He sat with us the whole night in the dark until morning light.

Reb Feybush the blacksmith would work all day, sometimes remaining until midnight in the smithy that was in the street of the Goys. After work he would come home. Before he managed to finish his meal he would already be sitting and reading aloud from one of the sacred books or rehearsing and memorising one of the Chassidic tunes in order to come prepared and practised, ready for the meal Melave Malka[335]. This was celebrated in the synagogue at the end of the Sabbath.

Then there was Yoyne the shoemaker, a strict and pious Jew, and Reb Nisn son of Reb Mordekhai, who for some reason was called by my mother's name Bathsheva. A pious Jew, he would spend the summer producing large sliced cheese called shvaytzer kez[336]. In winter he would trade in anything that came to hand from his work with Goys. It was with great difficulty that he supported his family. Despite that he had his sons - myself, my brother Itzkhok and my brother Mendl - educated by the best melamdim in the shtetl. He would save on food in order to pay tuition fees on time.

Then there were Shevakh Katz, very poor, quiet and devout, and Shleyme Levin and his son-in-law Leybush, the ritual slaughterer from a rabbinical family. His father, Moshke 'der rov', and his brothers, one of whom was Mordekhai, would sit days and nights over the Torah worshipping God, during which time his wife, and

[Page 88]

after that his son, worked in the shop. The same Shleyme Levin had a sort of oil 'factory'. This was a kind of wheel harnessed to horses. During the oil extraction process the seeds crystallized into a sort of solid block which served as food for the cattle. The seeds would belong to the owner of the 'factory' as payment for the extraction of the oil, while the oil itself remained with the farmer. This work continued for two months in the winter. The family made its living from this throughout the year in addition to milk from the cow that they kept in the house and from potatoes that they grew in the garden at the side of the house and from potatoes that they received from the 'Goy' in exchange for dung from the cow.

Yenkl Feldman der bukhlicher[337] came from the village and continued to draw his livelihood from it even when he was in the shtetl.

Then there was the yard of Zalman Velfils Kagan with the three families living in it. There is no way of knowing how they made a living. Despite that sons grew up and were educated in the Torah and to do good deeds.

It is obvious that it is impossible to describe every Jew of the shtetl, but in general it is possible to say that in essence, in terms of how they earned their living and their way of life, all the Jews of the shtetl were one family divided into two Chassidic schools: Chassidim of Stolin and Chassidim of Brezne. All lived roughly the same difficult crushing life. They made do with little, were content with their lot and raised boys and girls in the right path. A large number of them made aliyah to the Land and were among its builders…

| |

Mordekhai Lopata

Eyn Vered |

[Page 89]

A few memories

The Jewish homes and shops were in the centre of the shtetl, and in the middle of the long street was a well from which water was drawn by a hand pump. Sometimes I would go with two pails to bring water especially for important guests, because this water was better than the water in the well in our yard.

Whenever the rebbe from Stolin came to Vysotsk there was great joy. They would dance, sing and get up early to visit him and seek his advice and ask mercy for good marriages, birth of children and so on. From the adjacent room I would listen to the women crying.

My brother Chaim, although he wasn't religious, would receive the rebbe hospitably and was pleased when he came. They met as friends for a conversation.

After my father was killed by the Petlyura people we - five daughters - were in deep despair. But Mother, in her faith, gave us encouragement, demanding more work and more 'energy' in order to survive. On the day of my father's death many Jews were rounded up by the Petlyura people in the centre of the shtetl near the pump with the intention of killing them. They were only saved by a miracle.

I remember a large fire in the shtetl. Many houses were burned and many families remained without a roof over their heads. That night one woman was seized with labour pains. As there was at that time no doctor in the town they looked for my mother to help the woman in labour. On such occasions Mother would become a doctor, and everything would turn out well. She would help willingly and generously.

My brother Chaim Ayznberg also loved to help his fellow man. I remember him in the days of the Russian revolution. He would make a speech in the synagogue and in the street about equality of rights for all human beings, about brotherhood and justice etc. Then Zlata, our neighbour, came out and called to us 'Then why doesn't he marry my daughter Yente?'

I remember more. The boys learned in the chadorim and the girls wandered about without lessons. Rakhel Kryvoruchky and I gathered them in Ryzhy's house and taught them Hebrew.

Our neighbour in the street was Hershil der shnayder[338]. He had two daughters, Chaya Reyzl and Khasil. This was a very clever family. The post office was also next to us for a time. Large horses with bells around their necks would bring the letters. On both sides of our house lived shoemakers. One of them, Pesakh der shuster[339], had a daughter Lea who would shout at me for picking up the wild pears from their tree that fell on our land.

Meeting anybody from abroad was very interesting. Fanya Rabinovych would come once a year to visit her sick mother or her brother Avram. She was beautiful. We listened to her stories with great enthusiasm. Mother's friends were Nekhama Shtoper, Lea Zalmans and Lea di fakterin[340]. This was a foursome of beautiful, healthy and clever women. Always happy and joking and jesting.

- Yiddish: orthodox 'opponents' of Chassidism return

- A non-Zionist Jewish socialist movement return

- cf. Genesis chapter 3, verse 9 return

- A training kibbutz – see pp. 92-95 return

- Yiddish: By my window in the garden return

- 'Forwards', the provisional name of the local Zionist youth organisation return

- teacher's return

- Yiddish: alphabet return

- On 2 November 1917 British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour wrote to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, confirming that the British government favoured the 'establishment in Palestine of a national homeland for the Jewish people' return

- Jewish National Fund, founded in 1901 in order to buy and develop land in Palestine for Jewish settlement return

- College for religious studies return

- A later chapter makes clear that he in fact returned to Vysotsk after the war return

- Handwritten copy of the Torah used during synagogue services and kept in the Aron HaKodesh (Holy Ark) return

- From German Generalstab: headquarters return

- Followers of Symon Petlura (Petlyura), born in 1879, a Ukrainian nationalist who became head of the government of the short-lived Ukrainian National Republic (1919-1921). Jews held him responsible for the wave of pogroms. He was assassinated in Paris in 1926 return

- Seven days of mourning return

- Quorum of ten men necessary for reciting prayers in the synagogue return

- Afternoon prayers return

- Evening prayers return

- North of Vysotsk, now in Belarus return

- 'Accompanying the Queen' (i.e. Sabbath), the third and final meal of the Sabbath return

- Yiddish: Swiss cheese return

- From the village of Bukhlychi, now just over the border in Belarus, the first station north from Udrytsk, the nearest railway station to Vysotsk return

- Yiddish: the tailor return

- Yiddish: the cobbler return

- Yiddish: the agent return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Vysotsk, Ukraine

Vysotsk, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Lance Ackerfeld

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 13 Jan 20166 by LA