|

by Michael Grines

Translated by Pamela Russ

The last Mohican of the teachers' gallery was Mendel Biber.

In his young childhood, he absorbed the religious spirit that his father – Aryeh Leib – planted inside of him.

Mendel Biber's father himself was a great Torah scholar. He studied for more than fifty years in the large private Beis Midrash [House of Study], and he was also a teacher of his own children. Mendel Biber left the town in the year 1867, and in that same year he married, and became a son-in-law that boarded at his in-laws' home.

Until the passing of his father-in-law, he studied Torah and knew nothing about earning a livelihood. But when the father-in-law died, he had to take care of providing for his family.

Earning a living took up all his time. He even began to forget about his birthplace and the people who lived there. His plan of putting away some earnings for the scholars, with time, did not come to fruition.

After being in this unfamiliar place for twenty-three years, he returned home, but it was after the great fire in the city, in the year 1888. At that point, he could not recognize the city. There was no trace left of the old shuls, Batei Midrashim [Houses of Study], as the fire totally destroyed everything. There were already new ones that had been built in their place. The only place that had remained untouched was the great Maharsha shul.

Mendel Biber did not find anything in the city that he had left behind some twenty years prior, as the Torah institution already had lost its shine, and of the older generation, there was almost no one left who would remember and could relate stories of the great personalities of Ostroh, or of its great historical events.

Then Mendel Biber asked himself this question: Should things remain this way? The new generation that arose would remember the present city as if it had been like that all the time, and they would never know if the city had possessed any great leaders.

This problem awoke in Mendel the desire to create something. The original plan from the past reignited in him, to create a memorial for the past era of Ostroh, and describe events in a book that were tightly connected to Jewish life of the past in the city.

This dream did not move forward easily, it was difficult to attain. The wellsprings, from which he would be able to attain the necessary information, was in the city's Pinkas. And tragically, the Pinkas

[Page 132]

|

[Page 133]

was destroyed. Also, the books that were printed in Ostroh, or in other cities, that were found in the shuls, Batei Midrashim, or anywhere else, were also all destroyed by fire.

Only one road remained open – the cemetery. That is, to decipher the tombstones upon which the names and praises of each individual were etched. (In the past, people were very careful to inscribe praises on the tombstones. The deceased's real achievements were expressed in the words of praise on the stone itself.)

But even here, the explorer had a difficult task. He found the cemetery in a chaotic state. The old stones were broken, thrown all over. Other tombstones were sunken deeply into the earth, the letters covered with overgrown grass, or even erased – unrecognizable.

Nonetheless, he did not give up. First, he put upright the tombstones that had fallen to the ground, and with his nails, he scratched out the mud that had blocked the letters so that he would be able to read the names. He also searched through the Pinkases and books.

Mendel Biber devoted himself to this work. He spent every day at the cemetery, digging up tombstones, placing them upright, and recording the names of the great learned ones and scholars.

For many nights, the author of the book “Memories of the Great Ones of Ostroh” did not sleep, was turning pages in the old books, and reading old handwritten letters, in order to find something useful for his work. He also went to Warsaw to search for more information, to Vilna, and to other cities.

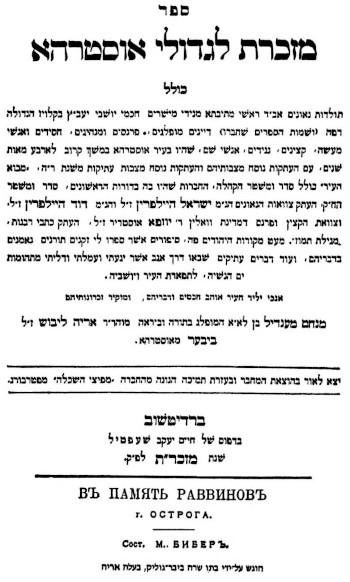

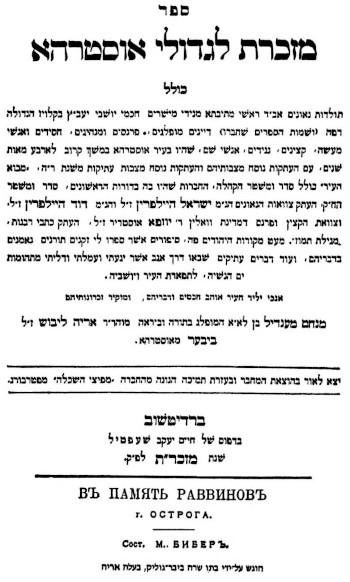

His joy was great when, finally, his work was published. It consisted of 346 pages, was in the year 1907, in Berdichev, with the financial support of the enterprise “Mefitzei Haskalah” [Dissemination of Enlightenment; under the organization to foster enlightenment for the Jews of Russia, founded in 1853] in Peterburg.

In this book, Mendel Biber put up a monument for more than four hundred Talmudic geniuses, scholars, and personalities who lived in Ostroh and who had raised the city to a level of culture with a world-class name during the period of raising knowledge of the Jews.

Until the last days of his life, Mendel Biber continued to safeguard the spiritual life of Ostroh.

Not his old age, nor his bent feet, prevented him from paying attention to the education in the Talmud Torah. Even compromised with his cane, he daily put strong steps forward towards the religious education institution. He made sure that the children would learn and remember all this when they would grow up.

For Mendel Biber, an educated student, a knowledgeable one, was an accomplishment. With a loving smile on his face, Mendel Biber would write a few lines on the gift that the exceptional students would receive after their exams, an impetus for the student.

Here is a facsimile of Mendel Biber's words, written with his own hand, on a “gift book,” that was given in the year 1915:

“My child! If you will use the words of your teacher for your own use, and you will infuse the words of your teacher for the coming years so you will not forget them, then this symbol of success will be an honor and a gift for you. A beautiful one and a rich one – forever.”

[Page 134]

M. Biber also held an esteemed place in learning, in the Krasnegir shul, where he used to study Midrash with the congregants. He is considered one of the last Mohicans of the Talmudic geniuses.

The author of this book, “When Life Blossomed,” feels a special admiration for Mendel Biber, as a leader and contributor of studies. The book “Memories of Great Ones in Ostroh” served as a guidebook for this work.

Mendel Biber died, in eternity, in the year 1917. His good name remains forever – as a name in eternity.

by G. A. Sadeh

Translated by Monica Devens

Among those of the last generation who immigrated to Israel, the name of Shmuel Shrira (Shreier) will be displayed in the first row of those carrying the flag of the revival. A learned Jew, a man in whom noble qualities and lofty characteristics mixed, a lively Jew with a sensitive heart and lofty idealism, a man of deeds and a vigorous activist, teacher and educator, author and journalist, one of the great men of Volhynia, whose reputation and deeds were also known outside of Volhynia. Those who respected and valued him, his friends and his students, who were counted among those who came to his home and heard his ideas, both when he was in the diaspora and here in Israel, were many. And even though there were not a few intellectual forces around him, his wonderful personality stood out everywhere in many, many areas of action in the communalism of Jewish Volhynia.

|

|

|

Shmuel Shrira |

A native of the town of Slavuta in Volhynia, of a Hasidic family for many generations, Shrira was a sponge of rooted Jewish peoplehood and already in his youth worked diligently in Torah and delved deeply into its sources. When he grew up – he left his town and wandered to Odesa. There he absorbed higher education, heard poetry and literature for a time from the mouth of Bialik, Klausner, and others, and finished general studies. All this came easily to him. From a thirst for academics, he transferred to the Academy for the Wisdom of Israel founded by Baron David GĂźnzburg in St. Petersburg and heard lessons from the greats of the generation, Shimon Dubnow, Dr. Y. L. Katznelson, and others. Afterwards, he continued his education at the universities of Strassbourg and Freiburg and thirstily drank the words of Prof. V. Novack, a researcher and interpreter of Tanakh, and other famous professors

[Page 135]

from among the great academics of those days. The Tanakh that had already attracted him in Cheder – continued to interest him even in the upper Beit Midrash and he deepened his study of the Book of Books and excelled. At that time, he began to publish notes and articles in “Ha-Zman” and in “Ha-Shiloah” (this one about the men of the Great Assembly). However, out of caution and possibly humility, he refrained from publishing articles about subjects from the Tanakh. He participated also in the Jewish-Russian Encyclopedia established by Brockhaus-Efron.

Some years before the First World War, Shrira accompanied S. Ansky and Yoel Engel on their trips through the cities of Volhynia and its towns and also in other regions in order to gather ethnographic material, ancient remnants of Jewish folklore. This was a stormy and substantial period in Shrira's life. When he would tell the legends to his circle of friends with emotion and excitement and sing the folk songs that he had collected then – he would create a special spirit of longing and awakening in his listeners and bring them to enthusiasm. Even then they saw in Shrira a rising force.

The World War came in 1914 and Shrira was thrown back to Volhynia. A new chapter opened in his life. Being full of knowledge, imbued with endless love for his people and his language, and full of faith in the revival and redemption of his land, Shrira took upon himself important public and national tasks. Here, during action, he was revealed as also possessed of organizational, educational, and propagandistic abilities. He worked a lot among the Jewish masses on behalf of the society to aid refugees, likewise as a representative of the society to spread education among the Jews and as a Zionist activist. His tasks completely consumed him and, being close to the broad layers through contact with them – there grew in him the aspiration of rescuing the masses of Israel from the vale of tears, to raise them up and to provide them with the spirit of revival.

In 1919-1920, he served as the administrator of the gymnasium in Ruzhyn, took part in communal life and Zionist activity there, and was, for that reason, beloved by the youth and the entire town. When the influence of the Yevskis [=Jewish members of the Soviet Communist Party] grew in government circles, the gymnasium passed over to Yiddishists and Shrira (the Hebraist and Zionist) returned to Ostroh and became a Hebrew teacher in the government gymnasium. In so doing, he also returned to his public involvement in Ostroh. Afterwards, he was called to serve as a guide and supervisor at the “Tarbut” school in Poland. He also worked under the auspices of the Joint as the administrator of the section for orphans.

Into every operation he sank all his efforts and the warmth of his heart.

As a combative Zionist and man of the Labor Movement (being a member of “Hitachdut” – “Tze'irei Tziyon” and “Ha-Po'el Ha-Tza'ir”), Shrira took an active part in the work of his party, appeared at conferences and meetings, was a member of local and central committees, and stood at the head of the work of the Keren Kayemet and Keren Ha-Yesod in places where he lived in Volhynia until his immigration to Israel at the beginning of 1925, and Shrira also knew how to work and how to put activists to work and to influence them and donors always.

It is especially appropriate to mark the period of his wide-ranging work in Ostroh. For many of his friends (and in particular for the writer of these columns) his ethical work is remembered beginning from the spring of the Russian Revolution, a period of independent Ukrainian rule and the announcement of Jewish national autonomy. These were tumultuous days in the Jewish street, all the parties ran around in the open, even the Zionist movement came out from hiding, and with this, an unsettled mood was felt: worry over livelihood, transition from war to peace, looting of Jewish property, and also murder of Jews (afterwards, a wave of pogroms in Ukraine). In those days, extraordinary forces were needed in order to direct, to advance, and to ensure matters, to manage politics, to fight the fight of Zionism and the communities and in general to stand guard. Shrira was the appropriate man for this, knowing how to win arguments, to resolve party and movement disputes, to wage the elections war, to order educational and cultural affairs, and to express opinions in public and community affairs – and he won the trust of the masses of workers. His simplicity, his wisdom, and the tenderness of his heart helped him a lot. He knew how to delegate everything from the warmth of his soul and from the storehouse of sayings steeped in living Jewish humor, and to convince not only friends of his opinion, but also people from the opposing camp.

And so we see Shrira as the founder and editor of the “Idische Vach” newspaper and later as the literary editor of “Vachliner Leben” in Rovno [=Rivne] during the two years until he immigrated to Israel.

With his coming to Israel, we see Shrira among the activists of the Keren Kayemet in Tel Aviv. And again he turned

[Page 136]

to education, worked in teaching in high schools, but problems of absorption in the homeland fell to his lot, like for many diaspora activists, without complaint about it. On the contrary, he continued to be happy and good-hearted in all his days and in all circumstances. Being free of the burden of community activism in Israel – his strong love for early Hebrew literature and Tanakh was renewed and he invested much of his strength and himself in books: “Introduction to Early Hebrew Literature” and “History of Talmudic Literature,” which he published together with the writer Shmuel Herr, and lastly his book, “Introduction to the Holy Writings,” which he completed at the end of his days (he only managed to prepare this book, but did not get to see it published). His friend, Zalman Rubashov (Zalman Shazar) says in the introduction to the book:

“…and this book, the last of his strength, was the beginning of his literary desire in ancient days … in books he bestowed upon the people works that would be useful in bringing the Hebrew student in the homeland to ancient Hebrew literature, to know it and to love it.”

In fact, the number of Shmuel Shrira's students is not small, some scattered throughout the Yishuv and in the ranks of fighters on the front. And the nobility of the spirit of their beloved teacher, educator, and guide accompanies all of them. A few weeks before he passed away, he gave a lecture to the community in Tel Aviv on “Volhynian Jewry Day” and among other things, he said:

“Volhynian Jewry are juicy, and if Lithuanian Jewry are the brains of the nation – then they of Volhynia are her heart …”

And so great was Shrira's love for Volhynian Jewry, which knew how to remain faithful and how to honor one of its good sons, Shmuel Shrira, in life and in death.

by Michal Grines

Translated by Monica Devens

It's hard to get used to the idea that Chaim Davidsohn was taken from us and is no more. The image of this student in uniform who, in 1917-1918, was hurled into the work of the Zionist movement, body and soul, hovers before my eyes still. Students and youth assembled around his personality, abundant in youthful energy, drinking thirstily of every word that came out of his mouth, whether at Zionist party meetings or literary gatherings.

There was no area of public work in Ostroh, whether in the area of Zionist work or in the area of cultural, social, and socialist work, that Chaim Davidsohn did not find there a place to focus on and to prove honest sincerity and to sacrifice himself to the maintenance of all the institutions in Ostroh. He always showed extreme understanding of the needs of the whole, who were truly a part of his being. And when he would speak or offer a conclusion on a social subject, he succeeded always in his sound sense, in his logical and correct analysis, and his clear speech to conquer the hearts of his listeners.

It is worth noting the fact that, during the time that Zev Jabotinsky spoke in Ostroh, he did not overshadow the accompanying address of Chaim Davidsohn, who left a massive impression on all who were gathered. Even his ideological rivals recognized his supremacy against their will and valued him as a shining popular leader and protector of the interests of the Jewish public in the city.

His blessed activity was marked and known by all in the Zionist movement, in the national funds, in the “Tarbut” school, in the Zionist library, in the city council, in the drama section, in the orphans home, and more. He stood at the head of the work everywhere as engineer and organizer and also worked diligently to carry out the work plan as one of the regular workers, however he reached the height of his action and organizing ability in the Jewish community, all of which,

[Page 137]

from bottom to top, could boast of the work of his hands. He founded and nurtured with love and did not leave until his last day, when the two of them passed away as “one.”

The heaviest burden that fell on his shoulders and that he accepted with courage and love was, without a doubt, social assistance to the poor of the city, whose number grew from year to year. I remember his feelings of joy when he authorized the support that the Committee of Ostroh Natives in Argentina contributed in 1938 to the “Ma'ot Chitin” project, and further how much sadness and pain he felt when he did not have the ability to answer the requests every day of the year – for firewood, for medicine, for livelihood, and so on. Fate gave Davidsohn an unbreakable tie to the poor and the stress of most of the residents of Ostroh, and when he wanted to turn away and immigrate to Israel, his great desire, for which he had worked all his life, this possibility was denied him. “He must remain in the diaspora, a place where his service is most essential,” that was the answer of the Israel Office.

|

|

|

Chaim Davidsohn |

And indeed, when Chaim Davidsohn reviewed the situation of matters in his letter to the writer of these columns, he was full of faith and his heart overflowed with “naches” over the progress of the Jewish institutions in Ostroh, and these were his words:

“Despite the great poverty that exists in the city, one must note significant successes in the area of Zionist work: Keren Kayemet works without fault and in the “Tarbut” school, we have “without tempting the evil eye” more than 350 children. We founded a secondary school three years ago, too, and more than 150 children study there now. If we had our own building, the school would become famous.”

These words were written four months before the war with the Germans broke out. The condition of the Jews in general was completely bad and yet, in the city they thought about strengthening cultural and national life, and Chaim Davidsohn was the man who, with one hand, supported and aided the poor masses so they would not collapse and, with the other hand, held the torch of culture at a high level.

In 1936, he had the opportunity to leave the diaspora when the leadership of Keren Ha-Yesod appointed him as director of their operations in America along with the privilege of immigrating to Israel. However, his bad luck was that he was delayed in Ostroh and his fate was set to extermination in 1941 along with the community.

His good name will live in the hearts of Ostroh natives and this modest page of memories will serve as a memorial in the line of the exemplary activists of Volhynia.

by Z. Gerschfeld

Translated by Monica Devens

Leibush Biber worked in the local bank. Everyone thought of him as quiet and a little shy and no one would have thought to themselves that there would come a time that he would be one of the outstanding Zionists in the city and among the best speakers of the city residents. Over time they came to know his abilities and his Zionist tendencies and included him in secret Zionist work, particularly in one area – the Hebrew speakers' circle. This was a small group that met at set times in the house of the Liss sisters: the elder, Esther, the kindergarten teacher, and the younger, (afterwards Leibush's wife), who was a Hebrew teacher. The principal work of this group was the cultivation of Hebrew speech and the subjects for discussion were: issues of Judaism, Hebrew literature, and Zionist questions.

|

|

|

Leibush Biber |

The main speaker in this Hebrew circle was Leibush who had absorbed from childhood an atmosphere of Torah and deep-seated Judaism in the home of his father, R' Menahem-Mendel Biber, who was also his teacher and rabbi. The rich library of his father was also at his disposal, but he wasn't satisfied with this because the desire for general education overcame him and he began to complete subjects of general education along with the study of Judaism. As a Zionist and as a worker in a cooperative bank, he developed a great interest in the theory of cooperation – and according to his sister – even wrote a book about cooperation.

And now came the Revolution of 1917 and, on one clear day, we went from slavery to freedom, from Zionist work in secret to open communal work, and then, too, came the day for Leibush to work to the extent of his strength. He quickly overcame his natural reticence and shyness and became a speaker and convincer. He adopted a warm, popular style that tied the audience to him and his speeches in public gatherings were always full of interest.

Over time he evolved and became an outstanding personality in the public world of Ostroh. He was very active in the Jewish community, in the popular bank, and in the “Hitachdut” party, of which movement in our city Leibush was the leader and the life force and its official representative to all the conferences that took place in this period in Poland.

In the last years preceding the Second World War, he dreamed of immigrating to Israel with his family, but this dream was only partially realized: only his oldest son, Meir, managed to come to Israel and settle there, while Leibush and his wife, Feiga, met the same fate as all the Jews of Ostroh.

by H. B. Ayalon

Translated by Monica Devens

Zalman Gerschfeld began his public work as a clerk in the savings and loan bank, which was then the first Jewish public institution in Ostroh. Leib Spielberg was a good co-worker at the bank and a good friend in public activity and the two of them founded the first two Zionist societies in Ostroh in 1908-1909.

|

|

|

Zalman Gerschfeld |

Zalman Spielberg founded “Tziyon,” together with Zev Shulvug, Radoshcher, and others, whose members were students in the upper grades of the government Jewish school, and Zalman founded the “Molodoy Yevrey” (Young Jew), together with S. Tolpin, Feiner, and others, whose members were students in the Russian secondary school in Ostroh and older students. Over time, the two societies merged into one Zionist federation, whose activities paved the way for those to come.

Zalman Gerschfeld was able to turn his dream into reality. Unlike those who worked in secret and in danger for their lives, he was able to dedicate his best years to active Zionist work in the open.

With the legalization of the Zionist federation during the period of Polish rule, he moved to the Bokimer house in Warsaw, along with his wife Mala (Malka), where he continued to work and the next station in his life was immigration to Israel and the difficulties of absorption there. Until then, the complete fulfillment of the man and his dream, the activist and his work. Being satisfied with little and with partial happiness, the lives of Ziameh and Mala were joyful with their family and the circle of their friends and associates.

But how much the Minister of History made us miserable, who brought us redemption through rivers of the blood of millions of Jews in the horrible Holocaust. And when the covering was removed from over the destruction of our city of Ostroh and the elimination of its Jews, he stood with all the warmth of his heart at the head of the rescue and aid operations of the Organization of Volhynia in general and of the Organization of Ostroh Natives in particular, where he served as chairman and spiritual father until his last day. And action brings action: he conquered the activity of memorializing the victims of our city in various ways and, in particular, through the publication of the Memorial Book, “The Ostroh Notebook,” joined the work of “Hechal Wolyn” in memory of the Jews of Volhynia, and was a member of the council of the World Union of Volhynia Natives, and in addition to all of that was active in the Tuberculosis League, in which he persisted from the beginning of its founding to his last day.

Zalman Gerschfeld wrote a shining chapter on the history of the Jews of Ostroh, their lives and their destruction, with his heart's blood and that was his long article in “The Ostroh Notebook.” With modesty

[Page 140]

and the spirit of friendship, he went among us, leader and guide, without making himself stand out, like the best of the tradition of the Gerschfeld-Bokimer family and this is how he will be remembered forever.

Ziameh Gerschfeld is the personality who is among us. Blessed with talents, gifted with great intelligence, with a sharp eye and revealing deep understanding, involved in the community and society. And so the society knew to value his unique qualities and laid important tasks upon him and he succeeded in fulfilling them for the good of the public and its benefit.

Zalman Gerschfeld revealed astonishing activity in the Zionist movement already in his youth, a time when it was still forbidden by the law that existed during the days of the Russian tsar to create political associations and organizations. Ziameh belonged to the “Me-firei Hok” [=lawbreakers], joined the underground Zionist “organization,” and was even one of its leaders as a member of the committee of the underground Zionist society, and it is doubtful that he was even 18 years old then.

In particular, his action increased during the First World War and the period of the Russian Revolution of 1917 which followed on its heels. And after the signing of the peace agreement and Ostroh was annexed to Poland, he invested his energies in the society of Zionist activity by establishing the institutions of the movement – the “He-Halutz” funds and more. His principal emphasis was on explaining the Zionist idea within the circles of the wider population, in addition to his work among the youth.

I, too, the writer of these lines, was drawn in after him and was among his students and I worked in his area. I had, therefore, the opportunity to see him up close in the Zionist field, full of youthful energy, producing light from high spirits. Those who worked in his area were influenced and joined him in action and the loss that will not return is terribly sad.

by Chaim Finkel

Translated by Monica Devens

The chapter of Ben-Zion H. Ayalon's life was part of a period of great upheaval. In his personal life, he stood out as a man of original ideas, a mannered man of culture, one with a crystalized character, absorbing Zionist ideas that began to percolate in the period in which Ben-Zion H. Ayalon grew up and worked. A learned Jew, a man in whom lofty qualities and elevated features mixed. A man with a sensitive and idealistic heart, an author, a publicist, a researcher of Jewish folklore, a talented editor, and his marvelous personality stood out everywhere, in our city of Ostroh and here in Israel. Always surrounded by respect and affection from the public because he was a symbol of public and intellectual integrity, a man of good intent and pleasant to mankind.

Ben-Zion H. Ayalon was born in Ostroh in 1901 to his parents, R' Yaakov Yosef and Nechama Baranik, who was a biblical scholar, a ritual slaughterer from a dynasty of ritual slaughterers, and who served as the principal cantor in the great Maharsha synagogue in Ostroh. He got his first education at the government school for Jews and later studied at the Russian secondary school in Ostroh and, upon completing his secondary studies, continued to learn pedagogy and was licensed as a teacher in the “Tarbut” network of schools in Poland. Because of his educational and public work, he earned a reputation as a man of principle, noticeable for personal qualities among which modesty and simplicity stood out, his wonderful personality prominent everywhere.

Already in his youth he stood out for his ethical essence, the fine psychological feeling that led him to penetrate and to get to know the characters of everyone who came in contact with him. Full of national and Zionist ideas, he joined “Ha-Shomer Ha-Tza'ir” when he was still a student

[Page 141]

in the upper grades of the secondary school and in a short time was among its leaders. From this movement, he found his way to the “Dror” movement –

|

|

|

Ben-Zion H. Ayalon |

– a radical, intellectual movement of which he was one of its founders and activists.

A journalistic ability was revealed in Ayalon and he wrote about ideas and outlooks in the pages of the movement's newspaper, “Al Ha-Mishmar,” where he published articles, notes, and lighter work to which he signed his literary name, “Ayalon,” next to his original name, Baranik. And when he became known throughout Volhynia as a gifted publicist with a sharp pen, he was offered the editorship of the newspaper, “Wolyner Cajtung,” and was its head editor in 1932-33. During this period, he published a large number of articles and research pieces in the field of Jewish folklore, which brought him great acclaim.

Ayalon took an active part in the public and cultural life of Ostroh between the two world wars, known as a man of polished style, and was among the leaders of the cultural activists in the city, taking an active part in every cultural, national, and Zionist event. He was very productive, too, at this time, wrote extensively in various journals and worked in the area of Hebrew language instruction for the masses and, in particular, for those who intended to immigrate to Israel. His lessons gave satisfaction to his students because he knew how to conduct interesting and concrete lessons.

|

|

|

“Wolyner Cajtung” from 1932 under the editorship of Ben-Zion H. Ayalon-Baranik |

[Page 142]

Ayalon had a strong love for the land of Israel, not just from a Zionist viewpoint, but rather he felt and believed that there was no other place in the world that could serve as a refuge for the Jewish people except for Israel. He expressed his belief in Zion in public meetings in the city and, in 1933, his aspiration was fulfilled and he immigrated to Israel to realize the idea that he had preached and worked for.

|

|

Books written by Ben-Zion H. Ayalon |

In Israel, he got a job as the secretary of the “Nordau” secondary school and then was engaged for 15 years in teaching in the professions of Judaism, Hebrew literature, and Hebrew language. Over time, he was appointed as the head of the secondary school, changing its name to “Tarbut” as a daytime institution and “Or” as an evening institution.

Ben-Zion H. Ayalon wrote a textbook in Hebrew and in English, published an anthology of Jewish folklore under the names, “Once There Was a Tale” and “Raisins and Almonds,” wrote many articles about various subjects for newspapers, both local and abroad. He was involved in collecting valued folk works and in arranging the literary-artistic material over decades and he proved himself as an important researcher of Jewish folklore, noted for appropriate scientific and artistic training. He succeeded in assembling the entirety of folklore entries for the first time in polished Hebrew in a special publication, “Anthology of Jewish Folklore in Eastern Europe,” from the Folklore Press in Tel-Aviv.

Ben-Zion H. Ayalon served as a spiritual guide

[Page 143]

to the “B'nei-Tsiyon” organization, to “Ha-Bonim Ha-Hofshiyim,” and to “B'nai Brith,” wrote and published five instructional books, and appeared on various platforms in Israel as a lecturer about the Masonic movement. In parallel with his public activities, he taught a class in Talmud and was a lecturer in literature and art.

Ben-Zion H. Ayalon was among the founders of the “Organization of Volhynia Natives” and its institutions and our organization, “Organization of Ostroh Natives in Israel.” He edited three volumes, “Volhynia Collection,” in which he published monographs on about 170 communities that were annihilated and edited 15 memorial books for Jewish communities that were wiped off the face of the earth by the cursed Nazis.

He was a faithful and devoted supporter of the remnants of Ostroh who remained alive. He and his wife, Miriam, engaged in providing help to the survivors of the city in Europe by sending packages of food and clothes and their home served as the address for new immigrants of Ostroh natives, worked to absorb them and to get them settled in Israel, and their home served as a meeting place for Ostroh natives. Ben-Zion H. Ayalon was the editor of “The Ostroh Notebook,” which was published in 1960, dedicated most of his time and energy to raising a monument to the splendid community of Ostroh so that the coming generations would know the roots and sources of those who came before them.

The members of the Organization of Ostroh Natives in Israel knew to value the distinguished son of our city who did so much for the organization in Israel and whose name will not be forgotten in our hearts and we will keep his memory forever.

|

|

|

Ben-Zion H. Ayalon and his wife Miriam (nee Rosenthal) at a party of the Ostroh Natives |

[Page 144]

by Chaim Finkel

Translated by Monica Devens

With respect and fondness, I mention the exalted figure of the celebrated educator, Yaakov Mordechai Nordman, who held the Jewish educational post in Ostroh and in Israel for many years.

|

|

|

Administrator of the “Aliyot” School in Ramat-Gan, Y. M. Nordman, lights the torch on Yom Ha-Zikaron for the Ostroh community |

Raising up the image of the teacher, Nordman, is not, therefore, only a responsibility of students to their teacher, but rather a deep spiritual need that has not yet found its expression. A distinguished educator, a man of culture and good manners – this is his attribute and the root of his soul.

Y. M. Nordman was not just a teacher per the accepted concept because his soul was noble. He had deep understanding and honest reasonableness in addition to expertise in all aspects of education.

There were three areas of activity to which Y. M. Nordman dedicated his life: educational, public, and Zionist activities. Love of Zion was sunk in his soul until his last days. A noble man, idealist, dedicated heart and soul to teaching and to Zionist activities. He saw in these areas a purpose and life desire. He shone his light on his surroundings and cast his beautiful spirit on us, too. He planted seeds in the furrows of young hearts that, in the fullness of days, sprouted Zionist deeds towards escape from the diaspora and immigration to Israel. Nordman was a scholar and an educated man, a man of character, gentle of soul. He was endowed with precise psychological intelligence and, in his lessons, tried to give his students a Jewish world view based on the values of Jewish tradition.

Only those who lived in Ostroh in the period between the two world wars knew to respect the man who, before the annihilator came upon Ostroh, educated an entire generation of students within the Jewish educational institutions that molded our spiritual and communal world, in the context of the special atmosphere of Ostroh, a sponge of Jewish and Hebrew culture as one. With its meaning according to each detail, Nordman was a wondrous image of empathy, of improvement of character,

[Page 145]

and of a desire for wholeness. Y. M. Nordman was original in everything he did. He excelled at innovating humanistic studies throughout his life. Ties of love and of deep spiritual connection were made between the teacher, Nordman, and his students. He was one of the well-known Hebrew teachers in Ostroh in those days. With his lofty and dynamic personality, he influenced a broad circle of students. He introduced an invigorated spirit in them and aspired throughout all his life to develop, to correct, and to improve what was and to broaden and complete what was missing.

|

|

|

The teacher Y. M. Nordman at a meeting with his students (in the center) |

|

|

Standing from right to left: Musi Kraidbord, Chaim Finkel, Chaim Sachish, Esther Shapira-Guterman, Eliezer Stol (Shatil), Avraham Rosenthal, Tanya Leikechmacher-Venderiger, Aryeh Shukhman-Shaham, Miriam Vaynshelboim, Izzy Bronstein |

Y. M. Nordman was one of the modern teachers who was a master of Tanakh in accordance with the Hebrew tradition illuminated by the Enlightenment. He was an excellent teacher and guide. Nordman knew not only how to impart knowledge to his students and to connect them with strong ties to the subjects that he taught them: Tanakh, Jewish history and Hebrew literature, but rather to awaken in their hearts the desire to enrich and complete their knowledge themselves.

The task of a teacher, according to Y. M. Nordman, was to develop in the student the desire and the belief in the student's ability to swim alone in the sea of the Talmud and the other subjects. Nordman was overflowing with optimism, strong in action, committed heart and soul to his students, and laid upon them the spirit of Jewish tradition and planted in their hearts love of the land and of the Hebrew language.

I had the great honor to be both his student and his friend. I met him in Ostroh as a teacher in the early years of my youth and I knew him also as an enthusiastic communal activist. He never tired of teaching or of Zionist-community activism.

Yaakov Mordechai Nordman came to Ostroh from far away and in the shortest time struck roots in the life of the city, taught in government schools and also in the Polish government secondary school where he taught Jewish religion to Jewish pupils following Polish law and the norm.

In practice, he taught Jewish history and Tanakh in his lessons. I remember that his lessons were accompanied by the words of Hazal [=our sages of blessed memory] and sayings from the best of Hebrew literature. His lessons

[Page 146]

became a fascinating experience for our growing spirits. He was an artist of shining wording and clear definition of sharp concepts. The students were captivated by him and loved him.

The Jewish community in Ostroh – the adult and the Zionist – saw in him an energetic representative who could represent them with ability and honor in government-public institutions and before the local government. Nordman was elected to the city council in the general elections among 16 Jewish elected representatives from among 24 representatives in the Ostroh municipality and served the essential needs of the Jewish residents of Ostroh faithfully.

He contributed a lot to the Zionist Revisionist movement in Ostroh through his broad knowledge, to advance the movement in the city, and everyone respected and honored him. Nordman was blessed with a great measure of diligence and perseverance, but he did not demonstrate his erudition except when he was asked to speak at various meetings of Jews in both Yiddish and Hebrew. He was an outstanding member of the community, gifted with broad intelligence and with deep knowledge in many subjects, but principally he was committed heart and soul to teaching and to communal-Zionist work. He spread the light of Torah at community platforms where he appeared as an enthusiastic lecturer on various Biblical and literary subjects.

|

|

|

Y. M. Nordman, head of the “Aliyot” school in Ramat-Gan speaking during a ceremony of the Ostroh community |

Nordman knew that the soil of the diaspora was burning under his feet and he did everything to leave the diaspora, to immigrate to Israel, and to integrate among the builders of the land. And so, he realized his dream, immigrated to Israel, and immediately became part of the education establishment. Here, in Israel, he dedicated himself entirely to Hebrew education and Jewish culture. He headed educational institutions for many years and taught hundreds of students, builders of the country. He was happy to see that, with the waves of immigration, hundreds of his past students came, too, whom you see today in all kinds of places: in kibbutzes, in the army, and in various enterprises, they have not forgotten Nordman, their teacher.

Despite his broad knowledge, he completed his education at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, even though, in the last years, he suffered from a serious illness that bothered him and took away his strength.

Nordman was a true and honest friend. He did not tolerate lying and, wherever he found deviation from the truth, he tried to bring the truth to light. He was among that minority whom nature has blessed with qualities that draw the attention of those around them. He was a man of principle and he lived and worked by them until his last days.

Despite his many activities, he did not forget the Ostroh community

[Page 147]

to which he was connected with every fiber of his soul. He was like a loving father to all, a gentle consoler and true friend. He participated in joyous family events of the Ostroh natives in Israel, who never let him go and saw in him one of the distinguished people who had worked in Ostroh between the two world wars.

The “Aliyot” school in Ramat-Gan, where Nordman was the administrator for many years, adopted the Ostroh community through his inspiration and year after year, on Tevet 10, they held a memorial ceremony with an interesting and impressive program that the students and faculty prepared. In these ceremonies, representatives of the Ostroh community were invited who spoke about the life of the community before the destroyer came upon it.

By having the Ostroh community adopted by the “Aliyot” school, Nordman intended to plant in the students and teachers first-hand information about the lives of the Jews in the Ostroh community before the Holocaust and this was the contribution of Y. M. Nordman, that the Ostroh community would live and would continue to exist for many generations.

This was Nordman, the man, and this was his path in life.

May his memory be for a blessing.

|

|

|

Y. M. Nordman (first on the right) on the memorial day for the Ostroh community at the “Aliyot” school in Ramat-Gan |

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ostroh, Ukraine

Ostroh, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 19 Feb 2026 by OR