|

|

[Page 4]

| The Maad Memorial Committee Members Chairman: Yosef Saczer–Eliaz, Haifa.

David Tibor Flegman – Mexico D.F. |

[Page 5]

The Beginnings of Jewish Life in Maad

In the 17th century, Hungary was divided into three parts. The western part was ruled by the Hapsburg dynasty; the centre was occupied by the Turks whereas the eastern part constituted an independent Hungarian principality.

The Hegyalja region was at the collision point of these three powers. It changed hands several times between the Hapsburgs and the Turks. In 1667, Maad was destroyed entirely by the Turks.

Initially the Jews came to Maad at the beginning of the 17th century. In 1609 the citizens of Kassau complained that Jews bought wine in Maad.[1] One of the responses of Rabbi Joel Sirkis from Cracow (deceased in 1640) deals with kosher wine production in Hegyalja.[2]

Systematic data on Jewish life in Maad are available as from the middle of the 18th century. Presumably, Jewish community organizations in Maad were established at that time. The 1720 census mentions one Jewish family in the village; the 1736 census lists eight Jewish families and the 1746 census lists thirteen: one of them a teacher – “praeceptor infantium Judeorum”.[3]. The Jews of Maad enjoyed the protection of three noble landlords, owners of the local estates.[4]

Sources about Jewish communal life in Maad in the second half of the 18th century are abundant. In 1774 the local court issued several verdicts resolving conflicts between Jews and gentiles. It is of interest to note that in many cases, the court protected the Jews against the gentiles.[5]

In 1750, the Baal Shem–Tov visited Maad during his journey in Hungary.[6] At the end of the century, wine–trade with Galicia was flourishing and the famous Jewish traveller, R. Ber from Bolichov, mentioned in his travelogue that in 1775 he found a prosperous Jewish Community in Maad.[7]

The first Rabbi of Maad was Moshe Wolf Littman who came to Maad from Poland. The 1771 census mentions his name and indicates that he is paying taxes and dwelling in his own house (in propria domu).[8] R. Yecheskiel Landau from Praha, the author of the Noda B'Jehuda responsum collection wrote a response to Rabbi Littman discussing the validity of a divorce letter in which the Yiddish transcription of the name Maad appears in an unusual orthographical form.[9]

In 1764 the Ner–Tamid Society was established in Maad and in 1769 there existed already the Chevra Kaddisha.[10] The records of the Chevra Kaddisha were kept since 1793. On its first page there appears the constitution of the society. It obliges the members to pay monthly fees and prescribes rules for the election of two presidents, gabbies (curators) and a book–keeper.[11]

[Page 6]

In 1771 there was a synagogue in the village, however it soon became too small for the expanding Jewish community and therefore, a new and impressive synagogue was built at the end of the 18th century which served the Jewish community until 1956. Its inauguration took place in 1789. This is a baroque–style building located on a high hill overlooking the whole village. The synagogue of Maad is one of the most exquisite synagogues in Hungary.[12][13]

The Golden Age of the Jewish Community

The 19th century brought changes in the life of the Jewish community. Maad became famous among the orthodox Jewry of Hungary. The scholarly rabbis coming to the village attracted students to the Yeshiva of Maad from all over the country and it became one of the famous Torah centres in Hungary.

The Jews manifested interest in municipal and national problems and at the end of the century when the thousand–year–old Hungary celebrated its Millennium all over the country, the Jewish community of Maad celebrated together with the gentiles.

The 1812 census listed 76 Jewish families living in Maad. It contained names of persons whose descendants lived in Maad until the Holocaust of 1944.[14]

No data is available about the occupations of Jews in Maad but on the basis of court decisions and responses in rabbinical literature, it may be inferred that most of them worked in wine–production and in wine–trade. In one document, for instance, we find that in 1812, Jews of Maad were accused of adulterating the famous wine of Hegyalja.[15]

In 1826 there occurred an important event in the life of the Jewish community of Maad. Its Rabbi, the famous R. Amram Rosenbaum Chassida whose scholarly commentary was printed in the well–known Wilna edition of the Jerusalem Talmud, left the community and immigrated to the Holy Land. Rabbi Rosenbaum settled in Safed and became one of the leaders of the Chassidic community. Two of his manuscripts are presented in facsimile in his books. One appears in a contract of buying a temple seat in the synagogue of Maad in 1825 and the second, in an agreement made between Chasidic and non–Chassidic Jews in Safed in 1829. The spiritual leader of the Maad community became the spiritual leader of the Jewish community of Safed.[16][17]

[Page 7]

The year 1848 became a landmark in the Hungarian history. The Hungarian people rebelled against the Hapsburg rule and led by Kossuth, they fought for Hungarian independence. The chronicles tell us that the Jews of Maad supported financially the Hungarian fighters. They donated 300 Fr for this purpose.[18] According to local tradition, a member of the Neuman family, who changed his name to Ujfy, joined the Kossuth troops and later followed the leader into exile.[19]

In 1857 an Association of Wine Growers was established in Maad. Its purpose was to improve vine cultivating practice, increase wine trade, arrange wine fairs, establish vocational schools for wine production, etc. The first president of that Association was the Count Andrassy who later became Prime Minster of Hungary. Among its members we find Adolf Lichtman, Nathan Tajtelbaum, Mano Zimmerman and several Jews from Maad. Their names appear in the proper alphabetical order together with names of courts, barons and other noblemen.[20]

In the 1860's, changes were introduced into the Hungarian political life. A compromise was reached between the Hungarians and the Hapsburg dynasty and in its wake, a process of modernization and economic prosperity spread all over the country. This affected Jewish life as well and they were granted emancipation. A great number of Jews took up secular studies and claimed that Jewish communal life and culture should be adjusted to the values of the environment. The rabbi had to be a scholar not only in Talmudic studies but also in the field of secular studies. Progressive Jewish elements calling themselves neologs demanded the Magyarization of Jewish life. However, radical orthodox masses launched active opposition to these plans. According to orthodox view, the slightest secularization might ruin Jewish tradition. The orthodox circles opposed the use of the Hungarian language in Talmudic studies, in religious sermons and in communal activities. For them, only one language was acceptable – the Yiddish. They even opposed the usage of Yiddish–Deutsch (a mixture of Yiddish and German). The orthodox elements understood that they could not stop the process of secularization and therefore they strove to divide the Jewish communities into separate orthodox and neology sections. The rabbis of Maad actively supported such a division. R. Amram Blum (the grandson of Amram Chassida who immigrated to the Holy Land) was one of the important supporters of such a separation. He was one of the rabbis who signed the famous rabbinical court decree against the establishment of a Rabbinical Seminary in Budapest.[21] This approach found explicit expression in his responsum collection Beth Shearim. A public petition dealing with this issue was signed by the leaders of the Jewish community in Maad and despatched to the appropriate ministry in Budapest.[22]

[Page 8]

In 1881, Rabbi Abraham Jehusa Hakohen Schwartz was elected to serve as Rabbi of Maad. His descendants continued to serve as rabbis and dayans until the Holocaust in many other Hungarian Jewish communities as well as in Maad. On his letter of invitation to serve as rabbi of Maad (1881), we find the signature of 115 Jewish heads of families. His son, Naphtali Schwartz was the Rabbi of Maad at the time of the Millennium festivities in Hungary. In 1897, he delivered a sermon in the synagogue praising the king and the Hungarian authorities for granting freedom to the Hungarian Jewry. He exhorted his congregation to remain faithful to tradition because as he saw it, the essence of freedom was – freedom to observe the Jewish laws.[23]

[Page 9]

The Twentieth century

The beginning of the 20th century marks a period of tranquillity and thriving progress for the Maad Jewry. In the Yeshiva more than 100 students were studying and the presence of Jews was felt in the village in activities of different sorts. The Weinhändler became famous in wine–trade and his products reached all the places where people consumed the Tokay wine. But the name Weinhändler, which sounded Jewish, was changed for Borsai. In the state elementary school, Jewish children with long ear–locks (peoth) studied together with Catholic boys and girls, sitting on the same benches. The Jewish community was an integral part of the village, sharing the gentiles' lot for better and for worse.

Between the two World Wars, the Jewish population decreased in the village. The cities attracted young persons and among them Jews. There was also some immigration to America. Young intellectuals seeking a better living left the village and settled in the neighbouring cities and thus the extremist orthodox elements carried increased weight in the community's life.

One of the centres of Jewish communal life was the Yeshiva. The date of its foundation is not known but when R. Amram Chassida left Maad in 1826 for Safed, R. Elimelech became the head of the Yeshiva.[24] The heads of the Yeshiva were well–known scholars. Students came to Maad from all over the country: from Patak, Bonyhad, Tokaj, Margitas, Miskole, Kassa, Eperjes, etc. Many Yeshiva graduates became, later on, famous rabbis in Hungary and in other countries as well.

From the beginning of the 20th century and until 1932, the heads of the Yeshiva were: Leopold Winkler, author of the Levushe Mordchai Responsum Collection and Rabbi Hayyim Ehrencreich, author of Kav Hayyim Responsum Collection. Winkler was one of the most revered rabbis of the Hungarian orthodoxy and his personality attracted numerous students to the Yeshiva.

It should be noted that the heads of the Maad Yeshiva published more than 25 Hebrew books, some of them Respondum Collections, Sermon Collections, Talmud Commentary, Haggada Commentary and a Historical essay about the Maad rabbis.

The education of the local children was shared by the state elementary school and the “cheder” or the Yeshiva. In 1736 there was already a Jewish teacher in Maad (praeceptor infantium Judeorum) but the Jewish school had been established only in 1788. In 1813, this school was closed down but it was re–opened in compliance with an order of the local authorities.[25] We do not know for how long that Jewish school remained

[Page 10]

opened, however, by 1890, Jewish children studied in the state elementary school and since other denominations had their parochial schools, the majority of pupils in the state school were Jewish. In 1901 the parochial schools were closed down in Maad and children of all denominations studied in the state school. The state school was closed on Saturdays – an unusual arrangement for state schools.

The boys attended the cheder each morning before school, in the afternoons after returning from school and on school vacation days. These small cheder children returned home late in the evening walking along the village's dark streets carrying candle–lights in their hands.

Increasing Anti–Semitism

The fourth decade of the 20th century started with this peaceful coexistence between Jews and gentiles in Maad. There were no atrocities; no Jew–beating and it happened several times on the 15th of March (the Hungarian national holiday) that a Jewish child with corkscrew curls (orthodox peoth) would recite the “Talpra Magyar” (Petofi poem) to the whole of the celebrating community in Maad. The anti–Semite movement, which was gaining strength in Hungary, did not affect coexistence in Maad. In 1935, bourgeois circles established a club in the village in which Jews were accepted as members.

A central event in the village's life, at the end of the thirties, was the preparation of a monument for those who fell in World War I. The decision to erect such a monument was taken at the beginning of the thirties and for several years the cultural activities of the village centred on raising money for this monument. The Jewish community took part in this effort. They prepared two shows in the Hungarian language, and not in Yiddish, and all notables (Jews and gentiles) attended the show. Everybody was pleased with the contents and the proceeds from the show.

When the monument was unveiled, the Jewish community was represented in the celebration and the rabbi of the neighbouring Szerencs community delivered in Hungarian a patriotic speech which deeply impressed the whole audience.

Connection with Zion

Before dwelling on the tragic events of 1944, let us give a brief review of the Maad Jewry's connection with the Holy Land during the last two centuries: As mentioned before, R. Amram Chassida, the rabbi of Maad, came to Safed in 1826. Schwarz mentions in his book a graduate of the Maad Yeshiva called R. Tuvya Goldberg who became a rabbi in

[Page 11]

Jerusalem. In the 1930's, two families from Maad immigrated for religious reasons to the Holy Land.

Since 1870, the Rabbi Meir Baal–Hannes alms–boxes could be found in the homes of Jews in Maad collecting money for needy scholars in the Holy Land[26], and since 1930, there were also Keren Kayemeth collecting boxes in several houses. The extreme orthodox rabbis were strongly opposed to the Zionist movement but, nevertheless, the youth found its way to Zion. Several youngsters went to the Hachsharoth of the Zionist Youth movement. One of them, Tova Lewy, leader of a Hachshara in Budapest, was arrested by the authorities on charges of conducting communist propaganda disguised as Zionism.[27] Tova Lewy, Lea Lewy and Tibi Sigelbaum eventually succeeded in coming to Palestine before World War II. Sigelbaum Tibi had the privilege of returning to the liberated Maad as a soldier of the Palestine Jewish Brigade.

The young generation was dedicated to the Zionist idea in spite of it being prohibited by the local Jewish establishment. In the years 1937–47 the local Tifereth Bachurim Association was the carrier of the Zionist idea. They collected money for Keren Kayemeth, sold the Sheckel, etc., and finally, a Bne–Akiva local branch was established in 1939.[28]

Deportation

Anti–Semitism became violent in 1939. It started with agitation against refugees from Poland. In 1941 when the first deportation of Jews took place in Hungary, three families were deported from Maad in the Kamenic–Podols direction. Weeks passed by until the people of Maad found out that all of them had been killed. One year later, fifteen families were arrested and measures were taken to expel them from Hungary. All of them were natives of the village and were not Polish immigrants and thus they were entitled to claim Hungarian citizenship according to the Hungarian law. Their only sin was that they did not possess such a certificate. The village people were shocked by this attempt and the gentiles also intervened. The 15 families were returned to Maad from the route of their deportation to Poland: they could stay in Maad for another short while.

In 1942, men aged 21–50 were drafted into the Hungarian army into special Jewish Labour Units. Many men aged 50–60 were also drafted. Almost all the men of Maad were taken to the labour forces and many of them found their death due to the atrocities of the Hungarian commanding officers.

In 1943, there was still hope that the Hungarian Jewry might perhaps evade the fate of its brethren in the rest of Europe. However, these hopes were in vain. On the 19th of March, 1944, the organized annihilation of the Hungarian Jewry began. First they had to wear the yellow Star of David; then

[Page 12]

followed the concentration in synagogues; in the ghetto in the central city of the district and then deportation and finally concentration and annihilation camps.

The Jews of Maad were not ashamed to wear the Star of David. Maad was a small community and people knew each other but they wondered why they should be wearing it.

The order was given for conscription. The authorities demanded an up–to–date list of all Jews – young and old, healthy and sick.

Then came the great shock of their removal from their homes. They were concentrated in the synagogue and kept there for three days. The gendarmes kept them from escaping although no such surveillance was needed. Nobody wanted to escape and at the end of the three days, they left for the ghetto in Satoraljaujhely – the regional capital. But only for a few weeks as this ghetto served as a station on their way to death. Life was organized in the ghetto: 4–5 families were housed in a single room. Public kitchens (mess) were set up for single persons who did not have families to look after them – Jewish charity started to work within the ghetto. Those who lost their property took care of those who had even less.[29]

Some relatives from Budapest, where meanwhile Jews were still free, came to the ghetto and tried to persuade the people to escape, to come to Budapest, but they did not want to leave their families behind.

A few days before Shavuot, the ghetto was eliminated. Transports were dispatched to Auschwitz. The 230 Jews of Maad were sent in three different transports and when Shavuot was over, about 110 of them – those aged and the children – were no longer alive. Their fate was: gas and fire. And about 120 of those who survived the first selection began their fight and agony for survival in various labour camps. Only 10–15 percent of those who were taken to Auschwitz survived.

It has often been claimed that those who were taken to Auschwitz did not fight for their lives – that they succumbed to fate without much resistance. However, when the survivors recount their memories, it becomes obvious that they did fight. This generation, therefore, should not only feel deep compassion and pain for those who suffered such a cruel fate but should also be fully conscious of their heroic struggle for survival.

Let the reminiscences of deportees from Maad bear witness to this end: “Our main purpose was to remain together” tells one of them – “about ten persons from Maad stuck together and made an effort not to be separated from one another. We stood in a line hiding those who were weak. In the beginning, we put the children in the second line being afraid that they would be taken away because they were very young and later on, they stood in the first line hiding the old ones who became feeble. We did everything to keep up the spirit of the group. There was a case when we had to force somebody to take in the “food” we received,

[Page 13]

and to persuade people not to seek medical assistance when they felt sick because we knew what the fate of those who asked for medical help was. And above all, our efforts were to remain together. When the group was transferred from Auschwitz, we stood together at the end of the row in order to make sure that all of us would be put into the same wagon. Unfortunately, we failed in our attempt. When our turn came to enter the wagons, all of them were full and they separated us. Each one of us was put into a different wagon. Nevertheless, we met again and remained together”.

[Page 14]

The Failure of an Attempt

In 1945 when the greater part of Hungary was still under Nazi rule, Maad was liberated by the Russians. The first Jewish survivors returned to Maad. In a short while, seven Jews returned to Maad. They founded a collective; lived in one house and tried to build a new life. By 1946, there were already 40 Jews in the village. In 1947, they officially established a Jewish Community organization. They opened the synagogue and began restoring the Jewish institutions. There were again Jewish weddings in Maad and also burials. Apparently, life returned to its old patterns. In 1950, A Memorial Table was set up in the synagogue in memory of the martyrs of the Jewish community killed during the Nazi period. At its unveiling, the village was represented by its officials but they were not asked to hold speeches. The Jews did not feel like hearing apologies. Anyway, what could they have said?

In 1950, many of the Jews who returned left and in 1956 only 4–5 Jewish families remained in the village. The attempt to rebuild a Jewish communal life in Maad failed.

At the time this book was being published in 1972, only one Jewish family and two Jewish widows are living in the village. The history of a small Jewish community in the north–eastern part of Hungary comes to an end.

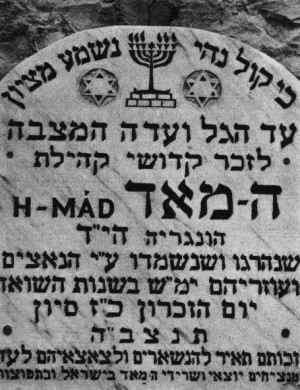

The Unveiling of a Memorial Tablet at Mount Zion

On the 2nd of October, 1973, about sixty survivors of the Holocaust from Maad and their families came together to unveil a memorial tablet for the martyrs. People came from all parts of the country – from the Galil and the Negev. Among them rabbinical and secular scholars, teachers, industrialists, businessmen, civil servants, military men, workers and farmers. The survivors became citizens of Israel and devoted their life to the building of their ancient–new country. They no longer live in a single small village but some common memories keep them together: the memories of childhood, the memories of an abandoned synagogue and of beloved persons.

Rabbi David Moskovits, one of the survivors and at present rabbi of the Belz–Yeshiva in Jerusalem, delivered a Misnayoth reading to the congregation. Mr. Yosef Salczer spoke about the glorious past of the Maad community. Rabbi Pasternak mentioned his efforts to commemorate the martyrs of the village. Zeev Salczer read the list of the martyrs and Arieh Lewy spoke about the spiritual heritage of the village.

[Page 15]

Jewish libraries contain more than twenty five books written by rabbis and rabbinical scholars of Maad. These books constitute objects of study for religious and secular scholars as well. Most of the students studying these books were never in Maad and most probably have never heard the name of the village.

The spiritual heritage of these books is the eternal monument of Jewish life in Maad and this monument will outlast all marble tablets.

|

|

| Monument to the memory of the Maad Martyrs in the Holocaust Cellar on Mt. Zion |

[Page 16]

From the eulogy said by Mr. Yosef Salczer–Eliaz

The destruction of Jewish communities in Hungary was not the result of a catastrophe caused by natural forces; neither volcanic eruption nor earthquake; nor flood destroyed these communities – the Holocaust if in effect an event which cannot be logically explained. The human mind cannot comprehend this. The more the years pass by since those dreadful events, the more diabolic appears this epoch in our eyes. Indeed, one cannot conceive these events but as an apocalyptic vision. One is perplexed and confused and cannot describe the cruelty of the Germans in annihilating the Jewish people. The Holocaust happened at daylight before the eyes of all nations and nobody came to avoid it.

Standing in face of the memorial tablet of the small community of Maad, our sorrow is deep and we express our feeling by quoting the words of Lamentations: “How doeth the city sit solitary that was full of people?”

We are still reaching for the meaning of the Holocaust and we can bear the memory of those days only if we believe in the age–old tradition that any Jew who was killed for being a Jew is a martyr and whose sacrifice strengthens the existence of the Jewish people. In line with this tradition, the Holocaust hastened the establishment of the Jewish State in Israel.

We mourn for those who dreamt about the Jewish State but are not here with us. Let this tablet keep their memory and tell their martyrdom.

Jerusalem, Mount Zion.

October 2, 1973

Tishre 5, 5734.

[Page 17]

From the speech delivered by Zeev Salczer.

The Torah says about Jacob: “And he knew it and said: It is my son's coat, an evil beast has devoured it”, and the Torah continues: “and his sons and daughters rose to comfort him, but he refused to be comforted”, Rashi remarks that Jacob mourned for twenty two years, until the day that he found out his son was alive.

It is striking that after the death of the high priest Aharon, mourning took place for only thirty days and similarly, after the death of Moses the Torah says: “And the children of Israel wept for Moses thirty days in the plains of Moab”.

One wonders why Jacob mourned for his son for so many years while the mourning period of Aharon and Moses ended after thirty days. Rashi answering this question says that one cannot be consoled when young people have been killed by beasts.

Our gathering at this memorial tablet is a tragic testimony to Rashi's views: Our children were devoured by beasts and this is the reason that our mourning has not ended. We meet here not thirty days but thirty years after their death and our mourning has no end.

Notes to the Hungarian and English text.

Ben Zvi Y. Erez Yisrael. Veyishuveha Bime Hashilton Haotomani, Jerusalem. 1970. Return

Schwartz P.Z. Shem Hagdolim. First Edition. Paks. 1913. p.206. Return

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Mád, Hungary

Mád, Hungary

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 26 Mar 2017 by LA