|

|

|

[Page 167]

|

Translated by Sara Mages We don't know who the first rabbi of our town was. It's only known that in the years, 1830-1860, a rabbi already sat on the Rabbinate chair in Lenin, but no one remembered him in our time. Prior to 1830, the Jewish community in Lenin was small and poor and wasn't able to support a rabbi.

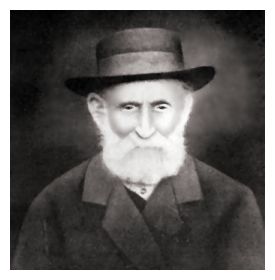

Anyway, HaRav R' Yehudah Turetski, who ascended the Rabbinate chair in 1860 and sat on it for sixty six full years, endeared himself to all the residents of our town. He studied the Torah day and night to fulfill the saying “You shall meditate therein day and night.” He only stopped his studies when he taught the laws of Kashrut, mediated between litigants who voiced their claims before him, officiated at a wedding, sold leavened food, etc.

[Page 168]

He lived in poverty and distress all his life. His financial situation slightly improved in the last days of his life.

The rabbi wasn't only respected by the Jewish community, the Gentiles, in the town and its environs, also respected him. The priest Johan, who visited him often, also expressed great affection towards him. During the rabbi's illness, the priest spent many hours next to his bed and talked to him on various subjects with the help of a translator. Of course, the Gentiles saw the rabbi as a holy man and when they met him in the street they greeted him with great respect.

We already said that he sat day and night and studied. When he encountered a difficult issue, he got up from his chair and paced slowly, back and forth, until the matter became clear to him. Then, his face lit up and he returned to the open page before him.

However, when the members of his community came to ask his advice, recount their troubles or ask him to mediate between rivals – he put his handkerchief on the open Gemara, welcomed them warmly, listened to them and found a word of comfort and encouragement to strengthened feeble hands and inspire hope in the heart on a difficult day. He made peace between rivals in the most wonderful and amazing way! He preferred a compromise on judgment.

As long as the rabbi saw that his help, advice and arbitration assisted those who turned to him, he wasn't sorry he had to cancel the study of the Torah. However, when someone bothered him with nonsense and idle talk, he held out his hand and said: “Well, well, Good night! Good night to you! Shalom! Shalom!”

Rabbi Yehudah Turetski had four sons and three daughters. All were talented and educated. R' Itche (Yitzchak), R' Aba, R' Shmuel–Michel, R' Moshe and his three daughters: Sheindil, Ethel and Basha.

R' Itche died at the prime of his life from a venomous snakebite. R' Moshe was a rabbi in one of London's neighborhoods. R' Shmuel–Michel, who was known by the name “The Karliner Dayan,” was appointed to served as a judge in Pinsk. He was kindhearted, well–versed and sharp. He dedicated his book of sermons, in which he gathered his father's sermons, commentaries, proverbs and sayings, to his father.

His daughter Ethel resided in the town of Petrikov on the Pripyat River. Basha and her husband, R' Yakov the slaughterer, l resided first in our town and later left for the city of Minsk. Sheindil and her husband, R' Hillel, resided in Kazan–Haradok.

R' Yehudah passed away at the age of 96. One winter day, when he left his house to go to the synagogue, he slid on the frozen snow, fell and broke his leg. The townspeople summoned the surgeon, Yavsienka, from Minsk. The doctor came with his assistants and nurses and treated him with great devotion. Despite the rabbi's old age, he managed to mend his broken leg and heal it – and there was great joy in town.

However, a few days later, the rabbi stumbled for the second time, fell and broke the same leg. The surgeon was summoned again, but this time he had to amputate the leg. Our beloved rabbi didn't have the strength to withstand this surgery and passed away.

A heavy mourning fell on the town which was orphaned from its good and amiable father. There were many days of mourning and eulogy because the man was loved because of his righteousness and great love to the members of his community.

Many rabbis and important community leaders came from towns, near and far, to pay their last respect to our rabbi and accompany him to his resting place. He was eulogized by Rabbi Itzale, the rabbi of the town of Lachva; by Rabbi Walkin, the rabbi of the city of Pinsk, and others.

[Page 169]

Translated by Sara Mages Our town was awarded that for over sixty six years a beloved and humble Jew, who loved people and was loved by them, served in its rabbinate. Although he wasn't considered to be an active man and didn't distinguished himself as a speaker and preacher – the secret of his good influence on the townspeople was his pleasant manners, his humility and great love to the entire town

He lived in a house that belonged to the community and stood behind the synagogue. His apartment was quite spacious, but poverty and shortage prevailed in it. He came to serve in the rabbinate in the days when poverty was the lot of most of the townspeople. Prosperity came to town when the office of the landowner, Agarkov, expanded its activities in the timber trade and employed many of the town's residents. By that time, the rabbi was already used to his poverty and didn't complain until the situation was unbearable…

Once, during the winter, at a wedding feast at the house of one of the town's notables, the old rabbi sat at the head of the invited guests – the town's rich and important homeowners. Also the slaughterer-cantor, R' Yisrael Chaim, and his choir, came to delight the bride and groom with their singing. When the guests were in a cheerful mood, the rabbi turned to the dignitaries and told them that he's freezing in his apartment because he doesn't have the means to buy wood to heat the oven… The rabbi's simple words deeply touched those who heard and caused uproar in town. Is that possible?! The rabbi is in such distress, suffering in silence – and no one noticed that!

The residents of the town were immediately called for a meeting, to consult on how to improve the economic situation of the rabbi, and the correct advice was found:

Till then, the rabbi's income came from the yeas that every housewife purchased on Thursday for the baking of the Sabbath challot. Until the meeting, the price of a portion of approximately ten grams of yeast was two kopeks. At the meeting, it was decided to raise the price of the packet to three kopeks and to also give the rabbi the right to sell the Sabbath candles which, till then, were sold in each grocery store. The shop owners didn't want to give up their right willingly, but after heated arguments were forced to surrender to the will of the crowd – and the sale of the Sabbath candles was transferred to the rabbi's house.

And the Sabbath candles of our townspeople illuminated and also warmed the rabbi's house.

[Page 170]

Translated by Sara Mages

|

|

When we come to place a memorial monument for our beloved town, and when we raise the memory of the men of virtue who lived and were active there, the image of my teacher and rabbi, R' Moshe Tomashov Zts”L, rises immediately.

I don't remember when I was introduced to him for the first time, but from that day I learned to know him and felt his entity. He was a little fat, had a long beard, his hat was slumped over his eyes and his coat hung over his shoulders. When he walked from the old synagogue to his home, his mouth murmured a prayer, and when he met a Jew he shook his head and said “Gut Shabbos! Gut Shabbos!” (twice), and continued on his way and his prayer without waiting for an answer.

I was his student for four consecutive years, and when I was in his presence I got to know him well and understand his nature, habits and way of life. Every day, summer and winter, he woke up from his sleep at four in the morning, sat and studied until Shacharit prayer. When prayer time came, he walked a long distant to the old synagogue even though the new synagogue was closer to his house. He came to the new synagogue for “Kabbalat Shabbat” and for Maariv prayer at the conclusion of the Shabbat services. He greatly extended his prayer and emphasized each word as if he was counting gems. He started with “Ma Tovu,” ended with “Ma'Amadot,” and continued to read a chapter of Mishnaiot before the audience. Although it was much to the chagrin of a few, they didn't dare to speak up and ask him to shorten his reading. On weekdays, after the Shacharit prayer, he returned home to eat his fill, which, most of the time, consisted of dry cake with a glass of goat milk. I remember that he made sure to collect all the crumbs and eat them, maybe out of poverty and savings, or maybe out of piety. He began teaching after this meager meal. We opened with a lesson in the Gemara. Naturally, there were those among the students who were talented and those who had a blocked brain. He worked harder with the latter and literally “chopped wood.” Most of the time the students didn't understand the lesson, but the rabbi was stubborn and repeated his lesson one hundred and one times until something entered their brain.

[Page 171]

Towards evening, at twilight, we studied the Tanach – or, as we used to say then – “the twenty four” [books of the Holy Scriptures]. This was the order of studies all the days of the week, and only on Friday the studies lasted until eleven o'clock in the morning. On this day, we engaged in easy studies: we read the weekly Torah portion, the Haftarah in “Taamei Hamikrah” and “Shir Hashirim.” On Sabbath eve, the rabbi allowed himself to engage in easy matters and told legends and jokes. On the Sabbath, R' Moshe didn't engage in everyday conversation and if it was necessary to say something, he said it in a few words in Hebrew. On the other hand, the rabbi allowed himself to speak in Yiddish in matters that were related to study, prayer and the explanation of an issue in the Gemara. Because of his humility he didn't eat any delicious food that he could keep for the Sabbath. If someone gave him a cake, or any other pastry on Thursday or Friday, he turned to his wife and said: “Keep it, Base, we'll bless it on the Holly Sabbath.” Yet, on weekdays, he managed to complete the number of blessings that he blessed every day, up to one hundred and one.

I'm unable to count and describe all his noble qualities. All the good qualities that our Sages counted in a noble man were folded in him in their entirety and connected together. He was humble, frugal, loved peace, fled honor, was far from envy and hatred, and loathed profit (he never demanded tuition from his students). He accepted everything with love and defended every person. The highlight of his virtues was his great love for all the Jewish people, but his love for the society did not detract from his love for the individual. If someone told him about a person who has sinned or committed an offense, he did not believe the story and said: “your eyes must have deceived you and you didn't see it clearly.”

He didn't hurt the dignity of a person and forgave an insult. His love of the Torah exceeded all bounds. Once, a student burst out and slapped him (the rabbi) on the cheek (today, forty-seven years after the act, my whole body trembles when I remember it). The same student, who was frightened and scared after his act, decided to correct the distortion and started to work diligently on his studies. However, it only lasted for a few weeks. The student gradually forgot the incident, returned to his evil ways and neglected his studies. Rabbi Moshe told him: “Slap me on the cheek again so you can pursue your studies.”

Even though the rabbi was constantly situated within the world of Torah, prayer and piety, he was a sociable person and was interested to hear the news from the world. He liked jokes and wise sayings and was gifted with a sense of humor. I remember, once, on Passover eve, when all the Jewish women were busy with the preparations for the holiday - with the polishing of the tableware and the cleaning of the house, R' Moshe turned to the home of my uncle, the son of R' Avraham Yitzchak Chinitz's sister, on his way home from the synagogue. There, he was given a cup of coffee and a pastry, and after he finished eating the refreshments he hurried to leave. They asked him – “why are you in such a hurry?” He answered them with a smile – “You understand, today is Passover eve and Base, my wife,

[Page 172]

is angry and needs someone to pour out her wrath on. If I stay here, she wouldn't have anyone to scold and raise her voice on.”

R' Moshe was childless, his wife was sickly and suffered from all sorts of pains and aches – and the order of the house was neglected. The floor was washed twice a year – on Rosh Hashanah eve and Passover eve. However, the rabbi excelled in a great deal of patience and never complained. In all the years that I came to his house I've never heard him complain, he received all the sufferings that came to him with love. Only once, on a winter night, when we, the students, got him angry and drove him crazy, he erupted with anger (I only saw him doing it once). He took off his silver watch and said: “Base, take the watch and sell it, I will expel these demons – and God will have mercy.” When we heard his words, the fear of death fell on us and we repented, if not for long.

We used to do all acts of mischief. In the hot summer days, when the rabbi lay down for his afternoon nap, we used to slip away to the river shore which was behind the rabbi's house. We collected all the fishing boats of the Christian fishermen (they were made of a thick wooden beam which was hollowed in the middle), tied them together into a raft, sailed to the middle of the river and played and enjoyed the water.

When the rabbi awoke from his sleep and saw that none of us was in the classroom, he went to the river shore and called: “Shkotzim, enough! Hurry up, enough!” We struck a deal with him: “Rabbi, we will come back if you promise not to beat us.” He promised, we returned, and he kept his promise.

His knowledge in the Talmud was amazing. When he was asked a question, he walked to the bookcase, took out the Gemara, opened it and pointed: here it is. It was said, that he finished the Six Orders of the Mishnah and Talmud thirty six times.

After I returned from the army I came to him every day to study a page from the Gemara and then, so to speak, already as a friend. There was no limit to his happiness. He used to give me a cigarette - it seems to me, that it was his only pleasure out of all the pleasures of the world which were strange to him and he did not enjoy them.

In the summer, he used to go on Sabbath eve to bathe in the river in honor of the Sabbath, and then he showed the wonders of swimming: swimming on the back, swimming under water, trimming of the toenails while swimming, and more. When he became ill and was confined to bed I was his helper during the day and also at night. One day he said to me: “My son, would I be able to walk again before God in the lands of the living?” I told him: “Rabbi, what are you saying?! It's clear to me that you will get better with God's help. After all, we are standing in the middle of Masechet Eruvin and we need to finish it and start another tractate.” He answered me: “my brother, Mordechi–Yoshe, died at the age of 72 and today I'm also 72. I doubt that I will live longer than him.” And as he said, so it was: he passed away on the same week.

Many accompanied him to his resting place. They said that Lenin had never seen such a well–attended funeral.

[Page 173]

Translated by Sara Mages HaRav, R' Nachman Wasserman, came to serve in the rabbinate in our town after the death of R' Yehudah Turetski. He was a Jew with an imposing figure, clever and well–liked. His house was always full of townspeople who came to consult with him, ask “questions” or litigate before him in monetary matters.

R' Nachman was a talented speaker and when he delivered his sermon on the Sabbath the old synagogue was full to capacity.

However, he didn't stay in our town for long. Shortly thereafter he moved to the city of Stavisk near Łomża.

As was customary in Jewish communities, the chapter of electing a rabbi started immediately after the departure of R' Nachman and lasted six months. The townspeople, who split into two camps, couldn't reach an agreement between them. When a rabbi was found, one side was satisfied with him – but the second side disliked him, what was good in the eyes of the second side – was rejected by the first side – and so forth. Meanwhile, our town was awarded to hear various sermons. Each rabbi, who came to present his candidacy for the rabbinate, gave his sermon, and since many candidates – young and old – came, an abundance of sermons and speeches rained down on our town. The old synagogue was filled to capacity on Sabbath eve, on the Sabbath and also on weekday evenings. Men, women, boys and girls came to listen and see the candidate. Obviously, each candidate came and gave his best sermon, and the members of our community weren't tired of hearing and listening. A few of us, who were quick to listen and comprehend, were probably able to go to one of the towns in which the rabbinate chair stood empty and orphaned, give a high quality sermon and present their candidacy to the rabbinate, if… if they wanted to…

However, the abundance of sermons didn't make the members of our community any wiser. On the contrary, the more they've heard, the more they got confused and didn't know who to choose and who to despise. Finally, the members of our community overcame their confusion and HaRav, R' Moshe Milstein, who was nicknamed “R' Moshe'le from Warsaw,” was elected rabbi of our community. He was a handsome young rabbi, was a great scholar and knew several languages. He had a fine voice and many loved to hear him when he taught and when he led the prayers at the synagogue. He was involved with people and knowledgeable in world's affairs. His five children were beautiful. He sat on the rabbinate chair for thirteen years and was the last rabbi of our town. He was murdered by the defiled murderers together with the members of his community, his flock.

The Holocaust chapters already told about the troubles and torture that he endured in the hands of the defiled Nazis, and the abuse he had suffered when he was still alive.

To his dying day he predicted, with great confidence, that the evil regime would fall and proved it with conclusive and logical evidence that were taken from the world of politics in which he had an extensive knowledge.

[Page 174]

Translated by Sara Mages

|

|

He was handsome and tall and all, who saw him for the first time, stood in amazement and said: “Did Dr. Herzl rose from his grave?!” because it was the image, the height, the facial expression with the beautiful black beard, and also the beautiful shapely lips.

He was one of the six son–in–laws of David Greiv and had a good and secure income. His spacious house, which stood in the center of the town, served as a hostel for passerby. He devoted himself to public affairs and was the one who initiated the building of the new synagogue. Thanks to him an elaborate building was constructed and for many years he was the Gabbai [beadle] of this synagogue.

He was also gifted with a pleasant voice and many enjoyed hearing his prayer when he led the prayers at the synagogue, especially on the High–Holidays.

His sons immigrated to the United States and settled there. In 5681 [1921], he also left the town to join his sons in United States. There, he was appointed rabbi of one of the synagogues in Brooklyn.

After the First World War, when the economic situation in our town worsened and many of its residents suffered from shortage, R' Avrom–Yitskhok Chinitz organized the support of our townspeople in the United States to the needy residents of our town. Nothing stopped him from action. Despite his old age he participated in all the meetings of the former residents of Lenin, even winds and heavy rain did not stop him.

All the great activity for the benefit of the needy of our town was concentrated at his house, and all the concern for the town leaned on his shoulder and the shoulder of his daughter Itka. Both worked over their ability. The former residents of our town, who saw the good deeds of the father and daughters, treated them with great respect, affection and gratitude.

After his death, a large funeral was held for him in Brooklyn and renowned rabbis eulogized him. The members of his community, the former residents of Lenin in the United States who were orphaned, mourn him…

[Page 175]

Translated by Sara Mages In memory of my father my teacher, R' Yisrael–Isar HaLevi Nekryz z”l, and R' Zalman (Zama) Schmelkin z”l

“But he gives grace to the humble” (Proverbs 3:34). Both were born in Slutsk and both were excellent Yeshiva students in Yeshivot Valozhyn and Słobódka. Both were proficient in Shas and Poskim and had great knowledge of Hebrew and secular literature. Each owned a permanent seat by the eastern wall among the “faces” of the community and its dignitaries, and both chose to turn down the Sabbath with the “common folks” at the table between the back of the Bima and the door. Both treated the child the way they treated an adult, the poor as the rich, knew to consider the views of each and point out an error in a pleasant way and convincing evidence.

A loyal friendship prevailed between them. Both sat on a bench and talked and an audience, mostly young, stood around them and listened to their conversation. The topics of their conversations were: ancient and modern literature, explanation of difficult verses in the Bible, the commentaries of Ibn Ezra and his riddles, witty and serious issues in the Talmud and matters of utmost importance in the political world.

Despite their friendship, their path split in the education that they've given to their sons. My father z”l gave his sons a traditional Hebrew education, national and Zionist, because he himself was one of the first members of “Hovevei Zion” in our town. R' Zalman gave his sons a general secular education which contained a lot of sympathy for the revolutionary movement in Russia.

Yet, my father z”l and R' Zama z”l knew to respect each other's opinions.

The two were divided in their opinions after the outbreak of the First World War: R' Zama z”l said that he was sure that Germany will win the war and its victory would bring salvation and blessing to the entire world. This victory is especially important for the Russian Jews, because it would release them from the regime of Czar Nicholas and his discriminatory laws against the Jewish residents. R' Zama z”l based his opinion on all sorts of imaginary evidence and proofs. My father z”l argued against him that Germany will fall and Russia, France and England would win the war, and proved his opinion with logical reasoning.

It goes without saying that R' Zama z”l had the upper hand for many days. All the mighty victories of the German Army in the battles were his victories. He used to come to the synagogue in a celebratory mood and call: “Didn't I tell you that Germany would win, now you can see with your eyes that all my words were verified.”

My father's situation wasn't good. He was on the defensive and claimed that the victories in battle are not the victory in the war, and only at the end of war it would be possible to know who won and who was defeated.

Every morning my father z”l read a page in the Gemara before an audience of students, and Talmudic legends from the book “Ein Yaakov” between Mincha and Maariv. Every Sabbath, before sunrise, he read the weekly Torah portion before an audience of workers. His listeners, his fans, devoured his words, which were in the spirit of the love of Zion and love of Israel, because he explained them well. At the same time, R' Zama z”l sat at the table, which was situated at the opposite wall, and preached to a crowd of young people about Moshe Rabbeinu, the first socialist.

[Page 176]

In those days, the revolution broke out in Russia, the Tsarist regime was eliminated, and R' Zama z”l saw the revolution as the essence of everything. My father z”l was skeptical and didn't believe that the revolution would bring salvation and redemption. Then, the relationships between the two friends worsened and the friendship came to an end.

When R' Zama z”l was asked to voice his opinion about R' Yisrael–Isar, he answered: “Yes, he's a great scholar, but he can't break free from his early opinions that their time has already passed.” When my father was asked to express his opinion on R' Zama z”l, he answered: “Great scholar, but he deviated from the path.”

With the Balfour Declaration my father began to believe that the days of the Messiah arrived. He was happy when his son, Chaim Shalev (Nekryz), immigrated to Israel. I immigrated after him.

In 1923, many young people started to leave Israel because of the severe economic crisis of that time. Among those who left were also a few from our town.

My father z”l was worried that we would also get caught in the panic of departure, especially after he found out that we already received a “demand” from our family in the United States. He immediately started to send us a letter after letter and warned us not to be hasty. “The country is only acquired with agony and sufferings” he wrote.

After we wrote him that it never crossed our mind to leave the country, he wrote us a letter in which he expressed his joy, hope and confidence that the bad days will pass quickly and we will live to see better days in the country.

My father z”l immigrated to Israel together with my mother. Their children, who preceded them and were based economically, were able to accommodate their parents and allow them a life of dignity and well–being. Since my father z”l didn't have the burden of livelihood, he continued to study and teach a page of Gemara before an audience. At first he taught at the synagogue of “Merkaz Baalei Melacha” and later at “Beit El” synagogue. My father taught in our town for thirty–five years and twelve in Israel.

[Page 177]

Translated by Sara Mages

|

|

Passed away in Tel–Aviv, 20 Tevet 5697 (1937) |

My father of blessed memory

My father, R' Yisrael Isar, was born in the city of Slutsk on 28 Kislev 5626 (1866) to his father, R' Azriel Zelig HaLevi Nekrycz, and his mother Chaya. He was orphaned from his father at the age of seven. His mother was a simple woman, but she cherished scholars and respected them. She sacrificed herself for the education of her sons and economized in order to teach them the Torah. His name came to fame at an early age. He was a diligent student with a perfect memory who never forgot anything and when he entered the Yeshiva he became famous as a prodigy. He fulfilled the way of the Torah literally: “Bread with salt you shall eat, water in small measure you shall drink, and upon the ground you shall sleep; live a life of deprivation and toil in Torah…” and took upon himself the burden of the commandments with love. He was known as a simple and honest man since his early youth, placed himself under greater restrictions, was righteous in all his deeds and fulfilled the will of his Father in Heaven.

When he married my mother z”l, Mrs. Chana, daughter of R' David Greiv from Lenin, he moved to live in this town and established his home there. His father–in–law, who was a prosperous merchant, guided him in the laws of life and the ways of the world, and opened a store for him. Soon, my father z”l emerged as a wise, honest and intelligent merchant, and a man who says what he thinks.

He never lived a life of wealth, but lived a life of honor – respected people and was respected and loved by all. Was humble by nature, escaped from power and honor and was satisfied with little. He was lenient and generous all his days, his soul couldn't get enough Torah and wisdom, and his straightforwardness bordered on zealousness. He didn't allow himself to deviate, not even a tad, from the path of truth in his trading and negotiation with people. Not only that he didn't believe that “it's permitted to deceive a Gentile,” he also claimed that there's no greater mistake than that, and there's no specific law on this issue in our sources. Therefore, not only the Jews, but also the Gentiles, respected him and said: “You can trust Isar with your eyes closed!”

He was God–fearing, careful with a minor mitzvah as with a major one, and with that, an ardent Zionist and a significant intellectual. When he was a Yeshiva bocher he earned his education in an hour which is neither of the day or the night. Because of his poverty he didn't have the means to purchase his own books, so he sat and copied a full Yiddish–Hebrew dictionary by hand. He was one of the subscribers of “HaTsefirah”[1] and “HaZman,”[2] and also read a Russian newspaper and the best Russian literature. His Zionism was a bone of contention between him and his father–in–law.

[Page 178]

In the days when the Colonial Bank was founded, he preached Zionism from the synagogue's Bimah and excited the hearts to purchase shares. His father–in–law, R' David, who opposed Zionism and believed that the redemption of Eretz–Yisrael would be in the hands of God and the secular Zionists cannot bring the Messiah by human force – interrupted his son–in–law's speech and removed him from the stage. This open clash led to a difficult conflict and the friendship ceased for a year, until they reconciled.

His love of the Torah was an unconditional love and he never used it for a personal gain. He was a popular man who loved people. All his life, at first in the Diaspora and towards his old age in Israel, he tried to teach and plant the love of the Torah in the hearts of the masses in his usual manner – calmly, in moderation and in a voice full of sweetness and pleasantness. In his town, in Lenin, and later on in Tel–Aviv, he gathered around him a large crowd of students who drank his sweet words with thirst, enjoyed his explanatory power and his clear and instructive remarks which were seasoned with proverbs and poetic phrases according to the place, time and period.

His visionary soul, which longs for words of Torah and words of the living God, is folded in his commentaries on the Torah and Mishnah, sermons and Hadranim[3]. We, his sons and grandsons, pray that we would be able to publish his writings in a book. In this bundle of pages he expresses his devotion to the Torah and his desire to distribute his knowledge. His writings are sealed with a seal of a Jewish man, who believed, in his heart and soul, that: “The Torah will only endure in the person who gives his life for it.”

“A woman of valor is the crown of her husband” – so was Chana, my mother z”l, to my father. Even though their livelihood was meager and scarce, my father z”l didn't know shortage all his life thanks to her devotion, practicality and cleverness. My mother z”l helped him in matters of livelihood and even assumed the burden of managing the store. She ran her home with wisdom and love – baked her own bread, cooked, washed, sewed, and looked after the children. And not only that, she didn't complained and wasn't angry at her husband who immersed himself in business and the world as it exists, and set a regular time for the study of the Torah. But, “She does him good, and not harm, All the days of her life” [Proverbs 31:12]. She was proud that his candle didn't go out at night, and that: “Her husband is respected in the gates, When he sits among the elders of the land” [Proverbs 31:23].

After his sons immigrated to Israel, he didn't rest until both he and my mother z”l were brought to country. He was “lovesick” for the Land of Israel since his early youth, but this love didn't sever the faith and the feeling, which pulsed in his heart, that: “There is no Torah like the Torah of the Land of Israel, and there is no wisdom like the wisdom of the Land of Israel.”

He was sixty when he came to Israel weak and exhausted. His sons supported him with honor. Even here he quickly took his rightful place. Those, who came to the synagogue (“Beit El”,) smelt the scent of the Torah and gathered to hear his lessons. Even here he used his special measure of humility and fulfilled the practice “Humility is a fence around wisdom.” He showed understanding to the soul of the young generation, and honored the builders of the country and its pioneers. He didn't treat them out of zealotry, but out of understanding, forgiveness and faith in the righteousness of their actions.

My father passed away in Tel–Aviv on 2 Tevet 5697, at the threshold of his 72 year of his life, as his wife, four sons, his daughter, daughter–in–law and grandchildren stood around his bed.

“An honest and humble man, studied the Torah all his life” – so is written on his tombstone.

Translator's Footnotes

Translated by Sara Mages

|

R' Zalman Shmelkin, or, as he was called by the people in town and the surrounding area, Jews and Christians – “Z'ama” – was a son of an extensive and attributed family in the city of Slutsk which was famous for its scholars and intellectuals.

He studied in a “Heder” in his childhood and in a Yeshiva in his youth. He was given the title “Illui” [prodigy] in “Valozhyn Yeshiva” where he was a classmate of H. N. Bialik and the illustrious rabbi, Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski. He acquired a broad and comprehensive education in the Bible, the Talmud and its commentators, and in all the treasures of Jewish science.

Later, when he saw a different way than his, he turned secretly to secular studies and within a short time acquired a broad knowledge in Russian literature. This self–educated man became a treasure trove of Torah and knowledge, which merged in him in a wonderful way, because he was gifted with a quick perception, a sharp mind, wit, an exemplary memory, iron logic and wisdom of life

Above it all, R' Zalman was liked by us because of his noble qualities: his simplicity, nobility, modesty, social relation to others and cleverness.

His sharp sayings, his manners and his negotiation with people were full of wit, healthy intelligence and deep knowledge of life and people.

His knowledge in the Talmud was amazing. Talmudic law led him to read and explore the theory of Roman law. In this manner he acquired, through self–study, a thorough knowledge and expertise in civil and criminal law which was in effect in Russia. Expert judges and well known lawyers listened to his explanations and remarks.

His way was to always to stand by the side of the weak. He was always ready to give advice and assistance to those who have lost their assets, and managed to save the oppressed from his abuser. After a thorough review and a detailed study of the problem, he was able to find the “weak point” on which he based his claim against the abuser.

[Page 180]

|

|

He owned a permanent seat at the “new” synagogue next to the eastern wall among all the town's dignitaries. However, the humble preferred to remain in the shade and we never saw him go up to his place among the notables.

We always found him behind the Bimah at the table of the “common folks,” or on the balcony in the summer. He felt himself free there, as if he was at his own home. There, he conducted friendly conversations on current affairs, and his audience, mostly the members of the young generation, drank his words with thirst. His unwavering loyalty to the principles of justice, equality and democracy, and also his deep understanding in the suffering of the simple Jew, earned him the respect of all the townspeople.

By the way, there, behind the Bimah, he had a permanent interlocutor, his equal – R' Isar HaLevi Nekryz,

How did R' Zalman Shmelkin arrive to our town? R' Chaim Paperny travel to “Valozhyn Yeshiva” and asked the head of the Yeshiva to chose an outstanding young man for his granddaughter, Sara–Leah, daughter of his son Herzl. The head of the Yeshiva chose R' Zalman Shmelkin.

After his marriage to Sara–Leah, Shmelkin began to engage in the lumber trade – the most important industry in our town which was surrounded by virgin forests. He educated his sons and daughters in high–schools and universities, a matter that wasn't easily done during the “Numerus clausus” period of the Tsarist regime. His son, Dr. Yisrael Shmelkin, who passed away several years ago in the United States, was one of the few Jewish students who were able to graduate two faculties, science and medicine, at the University of Moscow. His daughter, Dr. Tehila Shmelkin, may she live long, who lives in the United States, studied dentistry. His daughter Chaya and son Eliezer continued their studies in Moscow after they were cut off from their family when the Polish border was placed. His young son, Moshe, a medical student at the University of Bratislava (Czechoslovakia), arrived to Israel after the Nazis took over the Republic of Czechoslovakia. He worked for many years at the laboratory of “Hadassah Hospital” and received a certificate of excellence from the Municipality of Tel–Aviv for his important discovery in blood types. To our sorrow, he died at a young age from a severe heart disease. May his memory be blessed. The only family member, who wasn't able to receive a higher education due to her poor health, was his daughter Feigel who suffered from asthma since childhood. After the death of her parents, she joined her family in Moscow and died there at a young age. May her memory be blessed.

R' Zalman wasn't always successful in his businesses. There were also periods of decline and crisis. However, he didn't despair. He continued his way of life and

[Page 181]

the education of his sons in high–schools and universities continued even after he got into trouble because of his debts.

Five to six years before the outbreak of the First World War, the winter was late in coming and the rivers and swamps didn't freeze. The traders' time table was disrupted, they weren't able to sell their merchandise and comply with the terms of their contracts. This crisis also affected R' Zalman Shmelkin.

According to the terms of his contract, he had to bring several thousand Rubles to the management of Agrkov's estate by a certain date, but he didn't see the possibility of raising such a large sum of money by the fixed date.

One clear day, an inspector, who was accompanied by several forest guards, appeared in the patch of forest where he began to cut down trees. He ordered the workers to stop their work on the basis of an order given by the management of the estate for the non–payment of the amount determined by the contract.

R' Zalman Shmelkin was very surprised by this act. According to his calculation he had two weeks to submit the payment. However, he accepted the decree, returned home, took out his contract with the management of the estate, and with great joy determined that the cessation of the work in the forest was a mistake. He didn't think for long, sat by his desk and drafted a lawsuit against the landowner. He demanded a compensation of six thousand Rubles for the financial and moral damage cause to him due of the hasty act of the landowner.

It was a first time that a landowner appeared as a defendant in the District Court by a legal demand of a Jewish merchant. For reasons of prestige it wasn't fitting for a noble landowner to litigate with a Jew. The management of the estate recruited the best lawyers and ordered them to do everything in order not lose this trial. However, all their efforts have failed, and all their claims and long debates didn't help. With his healthy logic, R' Zalman Shmelkin managed to overcome them in the District Court and also at the Appeals Court. This trial made waves in the entire area and R' Zalman Shmelkin's fame grew day by day.

The management of the estate filed an appeal to the Supreme Court because they wanted “drag” the issue and buy time so they will not have to pay the large amount awarded to the stubborn Jew. They wanted to bother him even more, especially after his financial situation deteriorated because of this trial.

One summer day, a carriage, which was harnessed to three mighty horses, stopped in front of the rabbi's house, R' Yehudah Turetski Zts”L. Milinritz, the estate manager, descended from it and entered the rabbi's house. The whole town was abuzz: What had brought the chief executive for a sudden visit with the elderly rabbi who isolated himself in a world of Halacha and study? All sorts of speculations sprung up, and there were many arguments on this issue among the local residents. Eventually, it became clear that the estate manager came to ask the rabbi to intervene in his trial with Shmelkin. He hinted to the rabbi that if he could persuade his opponent to compromise with him – it would greatly benefit all the Jews of the town which lies on his land.

R' Zalman Shmelkin, who was in a tight situation, didn't want to hear about a compromise and demanded an unconditional surrender according to the terms of the State Court judgment. And now, there was a new conflict that no one wished for.

At that time, R' Zalman Shmelkin built his new house on the lake shore, on the other side of the bridge, on land that its ownership was disputed between the management of the estate and the farmers community in the town.

[Page 182]

The management of the estate, who wanted to get even with R' Zalman Shmelkin because of the shame he had caused them when they were charged in court, filed a legal claim against him. It demanded him to demolish his house, which was built, according to their claims, on the estate's land and without its consent.

However, R' Zalman Shmelkin not only knew how to prosecute, he was also an expert defender. He mobilized the treasure of his knowledge in law and trial, and proved that he built his house under an agreement with the farmers' community who was the rightful owner of the disputed land. The plot, on which his house was built, was part of the land known by the name “Vigum,” meaning, grazing area, which was granted to the farmers when they were freed from slavery in 1861 and belonged to the community from which he received permission to build his house. In its judgment, the District Court recognized the farmers' ownership of all the disputed area which covered thousands of “desiatinas”[1]. This ruling saved R' Zalman Shmelkin's house from demolition, but he aroused a lot of anger among the town's Jews because many have lost the right to graze their cattle in this area. The farmers took advantage of this ruling, fenced off the whole area and didn't allow the Jews and their livestock to enter.

After the October Revolution, his eldest son, Dr. Yisrael Shmelkin z”l who a doctor in the Russian Army during the war, was appointed physician of a match factory in the city of Rechitsa and the whole family moved there. R' Zalman Shmelkin was appointed Justice of the Peace, but he didn't serve in this capacity for long. A civil war broke out and he returned to his town, Lenin, which was seized by the Polish Army. In 1921 Lenin was annex to the Polish Republic.

To get used to the new situation, R' Zalman Shmelkin tackled the study of the Polish language with a youthful vigor. He studied the laws of the news country day and night, memorized the rules of the Polish grammar, and in a short time was able to resume his activity in the Polish courts.

His health deteriorated towards his old age. His vision, which was impaired over the years, weakened and he lost his eyesight. He undergone several surgeries but all the efforts of the famous doctor, Dr. Pins from Warsaw, to restore his eyesight have failed. Dr. Pins, who was also a Yeshiva bocher in his youth, became very attached to his patient and spent a lot of time talking to him about religious topics. Despite his serious condition, R' Zalman Shmelkin was in a good mood and full of sense of humor. Once he asked Dr. Pins: “What is between you and Aharon HaCohen?” He asked, and he replied: “Aharon HaCohen made an Eygel [calf] out of gold and someone is making gold out of Oygel [eyes in Yiddish]. The answer hit the mark because Dr. Pins became very rich from his practice.

After he became blind, R' Zalman Shmelkin kept to himself in his home. Every day I spent a lot of time talking with him and read before him from the newspaper. He never lost interest in the events that took place in the big world and in our little world. At times, when he remembered a certain issue from the Talmud, he asked me to take out a tractate from the bookcase and open it on a specific page. Then, he showed me with his finger the place where I have to look for the necessary issue, and I read it before him. I was quite surprised by his clear memory which didn't disappoint him to his last day.

He died suddenly after a short illness with heart disease.

[Page 183]

Translator's Footnote

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

|

| R'Dov-Ber Baruchin (Died 5 Tishrei 5680 – 29 September 1919) |

The Jews of our town who survived the Holocaust and now live in Israel or elsewhere, remember well my father Dov Ber Baruchin z”l, as a very distinguished person, whom all residents of our town regarded with love, respect and appreciation. Indeed his renown was undisputed.

He had a blessed influence on his children. He implanted in their hearts, since their early childhood, love of Zion, as well as aspiration and longing for Eretz Israel.

I remember that a Hebrew newspaper was always present in our home: Hamelitz or Hatzefira and later Hatzofe. My father and my uncle Baruch-Yakov z”l were subscribed to the Tushiya Books. Under the guidance of our father z”l we absorbed a spiritual sense of life; he was happy that God blessed him with children who aimed to acquire knowledge and education.

I can still see before my eyes the image of our father absorbed in reading the Tanach [Bible] – whenever he had some free time from his businesses. This book never left his desk, and he demanded us to read it as well, day by day.

I remember the Sabbath evenings, when we, the children, were waiting impatiently for the Sabbath meal to end, so we could slip out of the house and run to town (we lived across the lake) and join our friends. However, our father z”l always began reading for us a chapter of the Bible or a legend from the Talmud before the festive meal was over; his reading, beautiful and full of feeling, touched our hearts and distracted us, preventing us from going out. As we listened to his reading and his stories, we enjoyed them so much that at the end we did not miss the parties and our friends.

As far as I remember, our father z”l never punished us; all of us regarded him with awe – not fear, but love and respect. We felt that his eyes were watching every one of us – he knew our character and qualities, so that he always found the right way to guide us best.

We loved to listen to the stories about the days of his childhood, his study at the Yeshiva, how he and his friend Lifshitz managed to hide, under the open Talmud volume, books in German and Russian, which they read secretly. This friend finally left the shtetl and went to Germany, where he completed his studies at the University. To express his appreciation he dedicated to my father z”l

[Page 184]

his doctorate dissertation. My father kept the Diploma among his letters and documents and I liked sometimes, when my father was not home, to look through his papers in his drawer. Once I was pleasantly surprised when I found my letters, which I wrote to him from Moscow, in Hebrew. I was glad that Father was interested to keep my letters at that time.

I remember walking many times with my father from the town to our factory. The walk took about an hour; I was never bored during those walks and did not notice the distance. These times were very interesting and instructive for me: my father taught me the names of every tree and enriched the lessons with stories from the Bible and the Midrash about animals and plants.

My father was alert to any new event in our Jewish and Zionist world. With his encouragement, my sister Beila z”l and her children made Aliya to Eretz Israel in 1913, to secure for the children an education at the Herzliya High School in Tel Aviv. He hoped that this would open the way for Aliya for the entire family. Among his papers I found an exchange of letters with Nachman Sirkin z”l, concerning our Aliya: he intended to buy a plot of land and wanted to know how many people will be needed to cultivate it and whether the sum of money he had would suffice. However, WWII forced my sister and her children to leave Eretz Israel since they were Russian citizens. My father's wish was not fulfilled.

Great is my sorrow, knowing that my father did not live to see the new Aliya to Eretz Israel, and even greater that he did not see my own Aliya in 1925. I can still hear his words of farewell to Efraim when we parted. He was excited and had tears in his eyes: “Do not cry – you should be happy and joyful; go with success and pave the way for all of us.”

He was full of life and energy, not knowing that death was waiting for him: two months after Efraim left, my father died on 5 Tishrei 5680.

My mother Elka (died 3 Tevet 5687), daughter of Yehuda Tziklig z”l, was a modest woman. She knew to read and write Yiddish, to say the prayers and read Tzenah Ur'enah. But the blessed influence of our father z”l could be observed: she was always busy with work around the house, and hated idleness and gossip. She was never too curious about her neighbors and acquaintances, was blessed with good qualities and gave charity in secret.

I often saw her pack a basket with food. When I asked for whom she was preparing it, she always replied “none of your business.” During her last years, before my Aliya when my father was no longer alive, she increased her charity work, without any of us at home knowing. Chana-Feigel was one of her most frequent visitors – and every time she brought another “order”.

I heard her asking my mother to prepare fresh, unsalted butter, fish cooked in butter, baked food etc. When I asked Chana-Feigel, just out of curiosity, for whom she needed those things, my mother answered curtly, as was her custom: “none of your business.” After she died, when I visited the town in 1937, I heard from the neighbors about her many deeds of charity.

May both their memories be blessed.

[Page 186]

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

|

| R'David son of R'Chaim Grayev z”l – died in Lenin, 8 Marcheshvan 5680 (aged 88). Mrs. Shprintze daughter of R'Efraim Berkerman z”l – died in Lenin, 10 Av 5681 (aged 86). My Grandparents |

Our grandfather R'David was not a great scholar, nor was he very knowledgeable in the Talmud and its commentators. He was content with studying Ein Yaakov, the Mishna and the weekly Portion of the Torah [parashat hashavua]. He was a God-fearing and honest man, and kept strictly all commandments. He cherished Talmidei Chachamim [Jewish great scholars] and fulfilled the word of Our Sages, in the Tractate Pesachim, 49: “One should sell everything he has, and marry his daughters to scholars of the Torah” – his six daughters were married to persons who were Torah scholars as well as generally educated, people of good deeds and diligent merchants. He loved in particular the Mitzva of candle-lighting at the beginning of the Sabbath day: When Sabbath approached, he would walk through the streets of the shtetl, even when he was already old and his legs were weak and aching, and announce in a loud voice “Sabbath is coming, the Day of Rest is here” and urge the Jewish women to light the Sabbath candles.

He had about fifty grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and the people in town used to joke: when one of his grandchildren came to his house, he would pinch his cheek and ask

[Page 186]

playfully and lovingly: “child, what do you want?” Indeed, his house was always full of boys and girls, sons-in-law and grandchildren and great-grandchildren, family relatives and guests. On holidays, when the prayers in the synagogue were over, the entire family, old and young, would gather in his house for Kiddush. The refreshments were fit for a king – cakes and cookies and other goodies from the blessed hands of our grandmother. The joy was especially great on Purim, when all members of the family gathered for the festive Purim-meal, to eat and drink and sing the songs, until after midnight. The Purim meal at my grandfather's house was a great sight to see: the sounds of joy and happiness filled the house, rose through the walls and were heard in town from end to end.

Our grandmother, a kind and modest woman, possessed rare and special qualities. She was an admirer of Torah scholars and was always busy with her charity work. In addition to her seven children, six girls and one boy, she raised many orphans, members of the family, and kept in her house her daughter Beile, a widow, and her three children: Eliyahu (died in Lenin of tuberculosis), Mendel (perished with his family during the Holocaust, in Lodz) and Yehuda (perished with his family during the Holocaust, in Pinsk). Her daughter Sarah lived in her house until she married (died somewhere in Russia).

Our grandmother was a pious woman; she helped relatives, neighbors and others and cared for the sick, with compassion and devotion. She donated large sums of money and her home was always wide open to assist the tired, the poor, the depressed and the hungry. Day and night was her heart attentive and ready to support and help, as much as she could and even more.

During the Days of Awe [Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur holidays] as the Jews from the neighboring villages came to our town to pray, entire families would stay in her house, which consisted of only one big room and a spacious kitchen, and nobody complained. The house was always filled with light and joy, and our grandmother welcomed everyone with a pleasant disposition and a cheerful face. For years and years she collected money from the residents of the town, and finally used the money to buy a Torah Scroll for the new synagogue. There was no end to her joy and happiness when the scroll was brought to the synagogue – she organized a festive gathering and was happy as on her wedding day.

Our grandmother loved her grandchildren very much and, unlike our grandfather, she knew all of them – their characters, their weaknesses and their needs, and tried to fulfill their wishes. She gave them Chanuka-gelt [“Chanuka money”] kindly and generously.

With her own hands she would spin kosher threads for Tzitzit and give them to the people in town; she would also prepare candle wicks for those who studied Torah at night, or early in the morning. We should remember that electricity was non-existent in town at that time, and people would study by the light of candles or a kerosene lamp hanging from the ceiling. This way she felt she shared the Torah study with the learners.

Our grandparents lived a life of contentment, faith and peace of mind. When I remember their pure personalities and their way of life, filled with love of the Creator and love of Man, modesty

[Page 187]

and confidence, I understand the words of our Sages (Tractate Berachot, 60:1): “Old Hillel was walking on the road to town, when he heard loud cries from the direction of the town. He said: I am sure it does not come from my house.” At first, this saying sounds strange: Hillel, the most modest man – how can he be so sure? The reason is this: he taught his family to accept everything with love and without complaint. He was convinced that the members of his family would not raise their voices, but accept their troubles without complaint…

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

My father R'Israel Glenson was a handsome man, with wide shoulders and a beautiful white beard.

“R'Israel the blacksmith” was a Jew who combined Torah and work – and the local rabbi once said that in his soul he carried a spark of the soul of Rabbi Yitzhak Nafcha, one of our great Sages.

Encouraged by the rabbi, he “read” [taught] a Mishna lesson every morning after the first Minyan. On Saturdays, the study group was divided: half of the people learned with the Rabbi, half with my father z”l.

On weekdays at Mincha [the afternoon prayer], he would leave his work and hurry to the synagogue, to read for his listeners from the Ein Yaakov book. By the end of the evening prayer Maariv he would hurry home and retire, so that he could rise at dawn and study the daily page of the Talmud. This was his custom day by day.

On Sabbath eve, before candle-lighting, my mother Lea, may she rest in peace, lit the big kerosene lamp, which spread the light over the room until midnight, when my father studied a chapter of the Talmud, with his friend R'Chaim-Yosef the shamash [synagogue attendant]. At one time there was a discussion between my parents whether to donate a Torah Scroll to the shul or buy a set of the Talmud, and our rabbi decided for the Talmud.

When my father was about 30 years old, he climbed on a chair in the synagogue to reach a book, was hit by lightning and he went into shock; of course he was given first aid right away, by the means available at the time, until he was conscious again; in six hours his hair turned white.

During many years he served as Gabbai [treasurer, supervisor] in the synagogue, and until his last day he was Gabbai of the Hevrat Mishnayot [Mishna Society]. He died in 1938 at the age of 74. He left three sons and grandchildren. Two of his sons and their families were murdered by the Nazis. One son and one grandson live in Eretz Israel.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lenin, Belarus

Lenin, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 05 Jun 2016 by JH