|

|

|

[Columns 23-24]

Dr. N. M. Gelber

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Donated by Natalie Lichtenstein

The year of the founding of the town of Lakhva is unknown. However, it is clear from documents that in his day, King Kazimierz Jagiellończyk of Poland (1444-1492)[i] bequeathed the city in perpetuity to the Kiszka family. We can see from a document from 1536, that portions of its lands belonged to the dukes of Odyncewicz and others. In the year 1513, Anna Kiszka, the only daughter of Stanislaw Kiszka, the marshal of the duchy of Lithuania and Wojewoda of Smolensk, married Jan II the Prince Radziwiłł Brodaty (the bearded). As a dowry, he brought to him the cities of Lakhva, Nesvizh, and Olyka. As time went on, areas that belonged to other landowners were acquired. The town was completely destroyed in 1655 by the Russian Vojevoda Prince Volkonski during the war of Czar Aleksei with Poland. However, the town was renovated with the help of Radziwiłł.

During the first half of the 19th century, Lakhva passed as a dowry to Stefania, the daughter of Dominik Radziwiłł, who married Prince Wittgenstein. It transferred to the ownership of that family.

Ten villages with 1,400 farmers also belonged to the area of the town. During the era of Russian rule, they were represented by five leaders.

From when was there a Jewish community in Lakhva? It is hard to determine this. During the era of the Council of the Lands of Lithuania, there was apparently a very small Jewish community there. In the list of the “Borders and Areas of the community of Pinsk” that was established in the regulations of the council from the year 5383 (1623), Lakhva is not mentioned among the communities.

The Jews earned their livelihoods in Lakhva from retail business. Since there was fishing in the Hryczyn ponds, they also were occupied in an ample fashion in the selling of fish and agricultural products of the villages of the region.

According to the census that took place in 1765, there were 157 Jews in Lakhva who paid head tax.

In 1789, a census was conducted by the commissar of the Polish Sejm (1788-1792). In it, it was determined that the Lachowickja parish (parafia)[*], which includes the city and the villages, had a population of 6,787 residents, of whom 445 were Jews.

In the second partition of Poland (1793), Lakhva in the district of Pinsk and Mozyr transferred to Russia, which changed the administrative order as well as the jurisdictional situation of the Jews. In contrast with the Russian politics in the conquered areas of Poland that it received in 1772 (Vitebsk, Mohilev), in which the Jews were given the rights of city residents (and in specific areas, their representatives were even included in the city councils and courts), efforts started in 1793 to improve the status of the Jews in the new areas.

In the politics of the Russian authorities, there was a desire to suppress the Jewish tavern keepers and lessees. This also forced the estate owners, who relied on “their Jews” for their business, to fulfil the edicts.

At that time there was an economic decline in Jewish life in the district of Pinsk, including Lakhva. However, a slow recovery followed. Despite the edict to keep Jews away from tavern keeping, Jews were occupied in the production and sale of liquor, as well as retail sale of liquor. Not many of them worked in the trades. The tradesmen included tailors, wax makers, wagon drivers, bakers, and butchers.

During the 18th century, there was a difficult struggle between the Hassidim and Misnagdim in Pinsk and its region. We can assume that the Jews of Lakhva were also intertwined in the vortex of this struggle.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Lakhva was annexed to the district (Ujezd) of Mozyr, which belong to the Minsk region.

[Columns 25-26]

In 1804, an edict was proclaimed by Czar Aleksander I to expel all the Jews from the villages by 1808. A “Government Committee” was set up in Minsk to carry out the deportation of the Jews from all villages of the Minsk region through the course of three years.

A census of the Jews in the cities and towns of the Minsk region, according to status[1] was conducted in connection with the edict of deportation.

According to the census[2], the following were registered in Lakhva: 39 Jews of the citizen class[3]; 3 tradesmen, and even one Jewish merchant[4]. This data proves that no Jew with assets greater than 500 rubles was found in the entire Jewish settlement of Lakhva.

As a result of this census, the Jews were granted equal rights in the towns. The merchants and citizens were permitted to elect and be elected to city councils (the Magistrate city council) and civic courts under conditions equal with those of the Christians[5].

There were 73 Jews in Lakhva in the year 1811. This is apparently only referring to the men, for there were 161 Jews in Lakhva during the years 1816-1819: of whom 75 were men and 86 were women[6].

During the first half of the 19th century, the Jews were the majority of the residents of the city, which consisted of 150 houses. The Jews earned their livelihoods primarily from retail commerce, and the purchase of agricultural products, lumber, and fish, which were sent to Minsk. The farmers around the city were occupied with the weaving of willow baskets. A factory was also set up in the city for plaited furniture, which was sold by Jewish merchants.

Regarding the community, Lakhva was no different than the other communities in the towns of Russia from that period. There were famous rabbis of renown in the city. The following are known to us:

1) Rabbi Avraham Dov-Ber the son of Rabbi Yosef Berkovitz. He was born in 1825 in Davyd-Haradok. He excelled in his unique talents and diligence already in his youth. He was expert in the revealed and hidden [i.e. mystical aspects of] Torah. He was supported at the table of his father-in-law Reb Yaakov Nachman Lifschitz for 18 years. He literally lived like a Nazirite. He never tasted meat, liquor, or cooked fruit. In 1859, he was chosen as the rabbi of Kazhan Haradok, and later of Lakhva, where he served until 1889. He was dedicated to study and Divine service, and he also concerned himself with the needs of his community. In Elul 5659 (1899) he left the rabbinate and made aliya to the Land of Israel. He died in Jerusalem approximately one month after his arrival in the Land, on 28 Tishrei 5660 [1899].

|

|

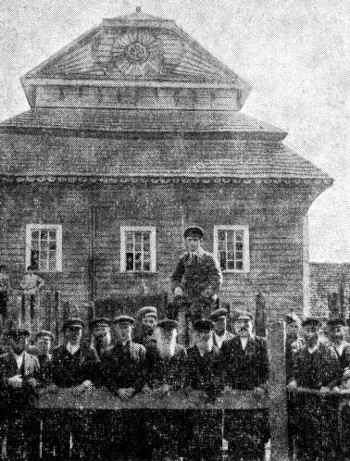

| The “Cold” Synagogue |

He had three sons: The eldest, Rabbi David, served as rabbi in Davyd Haradok from 1890. The second, Rabbi Mordechai, made aliya to Jerusalem. The third, Rabbi Yitzchak-Tzvi, was chosen as the rabbi of Lakhva after his father made aliya, where he served from 1890. Rabbi Yitzchak was born in 1858. From his childhood, he studied under the supervision of his father, who deeply influenced his spiritual development. He lived in the city of Kazhan Haradok and worked in business, but he continued to study and to teach there without any expectation of remuneration. He moved to Lakhva in the year 5659 [1899] after he was chosen as rabbi of the town. He also inherited his character and fine traits from his father. He concerned himself with the needs of his community and was beloved by all members of his flock. He wrote a great deal

[Columns 27-28]

of responsa, novellae, notes, and glosses on the margins of his Gemaras and books. His manuscripts were collected by Reb Yosef Weiner, but were not published and were lost with the destruction of Lakhva.

His livelihood came from the sale of yeast and candles. The business was run by his wife, the Rebbetzin Esther-Malka.

|

|

| Rabbis of Lakhva. Rabbi Yitzchak-Tzvi (Reb Itzeli) Berkovitz Above, Rabbi David Berkovitz (his brother) |

Rabbi Eliezer the son of Mordechei the son of Avraham David[7] Lichtenstein was the son-in-law of Rabbi Yitzchak-Tzvi, and inherited the rabbinical seat. His father was also born in Lakhva[8]. Along with Rabbi Eliezer Aryeh Lichtenstein, his brother-in-law Rabbi Avraham Chaim-Zalman Osherovitz, the son of Rabbi Yaakov, who was the rabbi in Bereza (Grodno district)[9] also served in holy service in Lakhva.

Rabbi Eliezer Lichtenstein concerned himself with the school with his energy and money. After graduating from the school, the students entered the Yeshiva and continued with the study of Torah. Through the efforts of his brother-in-law, a Tiferet Bachurim group was founded in Lakhva, in which the youth studied Gemara and Bible every evening under his guidance.

The two rabbis did a great deal to improve the state of the study of Torah and morality. Their influence on the members of the community was very significant.

When the Russians entered Lakhva in 1939, the rabbis transferred many of the cheder and Yeshiva students to Vilna, from where they were sent to Japan with the assistance of the JOINT. However, they themselves remained in Lakhva, for they did not want to abandon the community members in their time of trouble.

In the latter half of the 19th century the number of residents of Lakhva increased, but the Jewish population did not grow proportionately. In 1897, there were 2,426 residents in Lakhva, including 1,057 Jews – forming 43.5% of the population.

In 1920, Lakhva returned to Polish rule. In the census of 1921, the population was 3,420, of whom 1,126 were Jews (32.9%).

The population of the town grew by 40.5% from the years 1897-1921. However, whereas the Christian population increased by 67.5%, the Jewish population only grew by 6.4%[10].

* It is possible that this was also referring to Lachowica. This is difficult to ascertain. Return

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lakhva, Belarus

Lakhva, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 26 Aug 2021 by JH