A page from Rabbi Meir Auerbach's book “Imrei Bina”

|

[Page 205]

[Page 206]

By Abraham Avital (Toichenfligel)

It seems that memories, the bad and the good, the pleasant and the sad, which at one time were the essence of one's life and grey everyday existence-often come back magically from the depths and appear newly radiant, unreal , not quite the reality of things past.

I recall some of the characters who inhabited my past, in that town both near and far, where I grew up, Koło, or as we called it , Koil, on the banks of the Varta in far-off Poland.

Rabbi Wolf the Hassid

When I was still almost a child, on Shabbat and holidays I would follow my father to the “Shteibel”(prayer-hall) of the Gur Hassidim, in the short alley that led to the “Mikveh”(ritual bath), in the two-storey building that housed the oil-press of Rabbi Wolf Brockstein, there I first saw him. I still recall him standing motionless between the “Aron-Kodesh” (Torah cupboard) and the window. In the “Shmone-Esreh” (Eighteen) prayer Rabbi Wolf the Hassid stood like a statue. I as a child would look at the Hassidim at prayer and note their varied expressions, that ranged from the funny, or the ecstatic to the indifferent. But always my gaze returned to Rabbi Wolf.

As I remember him, he was short, an aged youth, his face that of an ascetic, furrowed, pale red, with a sparse grey beard. But it was not his outward appearance that gripped me. He had the quiet power of an ancient statue, his eyes shut, his eyelids quivering with passionate prayer, his lips hardly moving.

Who was he and what did he do? I do not know, but my father would sometimes speak of him:

As my father described him he was a sort of “Paul” or missionary of the Hassidim in our little town, daring in his youth to bring the message of the Baal-Shem-Tov ( a famous Jewish mystic) to a town which was all “Misnagedim” (opponents of mysticism). He was the first to set up a circle of Hassidim among the Talmud students and sons of the wealthy, including my father -whose own father was a “Misnaged” Rabbi-and who in the “Bet Hamidrash” (religious academy) taught ( between the Minha and Maariv prayers), not Hassidism but “The duties of the Heart” by Rabbi B. Ibn-Pakudah, the Sephardi sage.

Rabbi Yohanan the Hassid

In outward appearance he was the very opposite of the other. Tall and thin, like a dried “lulav” (palm-frond used at Sukkot). His inner essence- to use Hassidic parlance -was also different. He was lively, aware, in his speech and prayer. His hands and body moved strongly and his prayer like his speech was powerful and aggressive.

As I recall he would pinch children's cheeks and call them “sheigetz” (Yiddish: naughty).

His livelihood came from a little shop in an old wooden shack, with a tiled roof covered in moss. Apart from yeast for Shabbat Hallah bread-that housewives bought on Thursdays, I don't think he sold anything. Rabbi Yohanan was no businessman.He spent his days and nights in the Shteibel studying Torah and praying, or chatting with the Hassidim. The shop was run by a round plump woman with a broad scarf on her head that almost covered her eyes.

Rabbi Yohanan and Rabbi Wolf were childhood friends, now both elderly and revered by their Hassidic followers, like in the stories of Y.L . Peretz.

In his youth Rabbi Yohanan helped his friend in preaching the ideas of Hassidism.

I well remember the night when the Hassidim got the sad news that the Rabbi of Gur had died. They gathered at the Shteibel, and with them was my father. They sat on the floor , mourning in a fearful silence, broken only by quiet sobs.

Suddenly the door opened and in staggered Rabbi Yohanan, supported by two young hassidim. He sat on the floor, raised his arms to heaven and began crying bitterly, filling the room with wild lamentation.

Moshe Kott

He was not a rabbi, nor a “Mr”, neither a Hassid nor a bible scholar, but unlike many Jews he was a Zionist intellectual.

Those were times of searching and questioning, of rebellion and renewal in Jewry. Jewish boys who went from the “Heder” to the “Beit Midrash”, listened in awe to the changes around them. They heard of the Russo-Japanese war, of pogroms and revolution (what were they?), of words like Haskalah, Bund, Zionism etc.. and amid all their arguments and shouting one heard the raised voice of Moshe Kott.

When I was a bit older and already knew the meaning of words like Bund and Zionist I would creep secretly into a room where the Zionists had their meetings and there got to know Moshe Kott.

He spoke quietly, dispassionately, but conveyed his message with the passion of a Hassid. It was exciting stuff: we learned of Hibbat-Zion, of settling in the Land of Israel, of people like Rabbi Zvi Hersch Kalischer, of Drs Pinsker and Lilienblum, of a gifted writer called Ahad Haam, of the Bilu movement, of the charitable Baron Rothschild, and about the farming colonies - and our young hearts filled with yearning for that distant place. Then we learned of Zionism and Herzl, and our meetings would end with the lusty singing of Hatikvah, often accompanied by Moshe Kott on the violin, We treasure those memories.

The man himself was just an ordinary Jew.

He wore the same shabby black kapote, a black hat drawn over his eyes. Of medium height, broad-shouldered, a short reddish beard, that was his appearance. What was he like as a person? How did he contend with his poverty-stricken surroundings? Who knows?

He had a small shop by the river where he sold leather and shoes. His wife was tall and big, but childless. When she died, he remarried and had sons and daughters. But the economic hardships he faced left him little time or energy for Zionism, Herzl and the dream of the colonies.

The years passed and our studies took us away from the Beit Midrash as well as from the early Zionism of Moshe Kott.

In later years I saw him occasionally, white-haired now, leading a child by his almost empty shop, and wordlessly saying, please God, I shall yet raise the young.

Rabbi Katriel Shaladowski

He was a “melamed”(tutor), but not like just any other teacher. He was – for his time – “modern,” and “progressive” and many called him Mr Shaladowski, because he was more of a teacher than an old-fashioned “melamed”.

He was short and thin, enveloped in a black kapote reaching his ankles, unlike the kapotas of “progressives”. He wore a black hat like a traditional Jew. His beard was short and sparse, in brief: just another poor thin Jew… So how then was he also “modern”? – thanks to his insistence on grammar and exegesis.

He was the only melamed in town who led his pupils through the intricacies of Hebrew grammar, with a Polish-Lithuanian accent. His Bible class taught not only the traditional Rashi commentary but also the new interpretations of Moses Mendelssohn of Berlin. Some of the parents were uneasy but they let him prepare their children for Bar Mitzvah nonetheless.

He was modest and introverted. His voice was soft, his rhetoric muted. He took care not to offend, and was strictly observant, avoiding all contact with the Zionists.

The writer was a teenager when he first met this tutor, who treated him like an adult.

One evening after classes he was invited to the home of his teacher., who lived in a small room with a large table, two benches and a cupboard full of books. There were writings of the Haskalah (Enlightenment) movement, books of poetry and much more. All of them neatly wrapped and marked with his Ex Libris in careful handwriting.

For our melamed was also a poet. He would sit in his lonely room and pen verses, often didactic in form, in imitation of the great Jewish poets. He was also a Bible scholar, and consulted a German commentary, not one in Yiddish.

I heard that he spent his last years on Mt Carmel (Haifa) and was buried there.

But what of the Jews of Poland he taught? They were all swept away by the tempest…

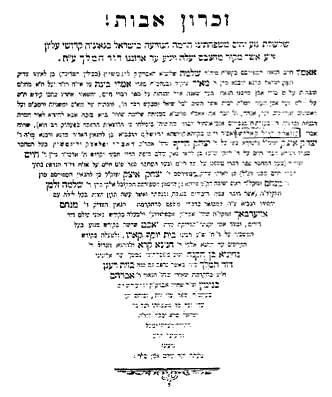

Rabbi Meir Auerbach, Av Beit Din of Koło

and the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem

By Dr. Aharon Brandt-Orban

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

To the memory of my father-in-law, Rabbi Avraham Shlomo Auerbach, z”l,

great-grandson and grandson of the rabbis of the Auerbach family and his wife

Sarah, may God avenge her, and my brother-in-law, Chaim Auerbach, may God

avenge him.

|

One of the most prominent figures in the list of individuals who acted in Koło is undoubtedly the figure of Reb Meir Auerbach, whose life story is a turbulent one. His name will be remembered among the Zionists of the 19th century, and he did much for Jerusalem and for the settlement of the Land of Israel. His long path from Koło to Jerusalem is crowned with blessed actions for the benefit of all.

Reb Meir Auerbach was born in 5575 (1815) in the city of Kovel, and he was a descendant of a family of rabbis and great men in Israel – “the lineage of our distinguished family is dates back to our Lord King David, may God bless him” – this is stated in the genealogy of this family. When he reached the age of twenty-five, he became famous for his knowledge and virtues and was appointed rabbi in his hometown, where his father had previously served as rabbi.

In 5606 (1846), six years after the passing of Reb Aharon Koyler, Reb Meir Auerbach was called to serve in the rabbinate of the city of Koło. His material condition did not improve as he moved from city to city, but here he found an anvil for his hammer. The Beit Midrash and its students captured his heart, after all he arrived to the city of Torah scholars. For nine years he headed the rabbinical here and was greatly appreciated. In his books he speaks of our city as a man who remembers the good years he spent in Koło, he calls it “dear Koło”.

The Kalisz community approached him asking if he would be willing to come to them and serve in its rabbinate, and he granted their request in 5615. In this city he also reached financial prosperity. During the three years he worked here, he also engaged in trade. He distributed some of his money among the city's poor and made large donations to charitable institutions, and the rest enabled him to fulfill his dream – to fulfill his favorite commandment, that is, to settle in our Holy Land. In his sermons to his congregation, he never stopped talking about “the settlement of the Land of Israel, which is the beginning of our redemption”. In 5619, he fulfilled this in person. The property he brought with him served as his primary source of livelihood, so that he would not have to depend on others.

Reb Meir Settled down in Jerusalem, and even here he continued to act to raise the profile of Torah students. He invested great energy in the foundation of the “Ohel Yaakov” yeshiva, and its name became famous. The Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem appointed him chief rabbi of its community.

He was not fortunate enough to sit in peace. When he asked to appoint shochets who would act according to the customs of the Rama (Reb Moshe Isserles, the great arbiter in matters of prohibition and permission, rabbi in Krakow

[Page 213]

in the sixteenth century), the Sephardic community became angry with him. A great controversy broke out, and Hakham Bashi, Reb David Hazan, came out against him, and the quarrel reached the court of the Turkish Sultan…

Finally, his righteousness was revealed. His ambition was always to find the unifier, not the divider. In his fight for the kosher slaughter, he sought to allow the residents of the many neighborhoods in the city to act according to their customs, not to impose the will of the Sephardic community on the Ashkenazi, or vice versa. Soon, they saw him as a unifying force.

Upon his arrival in Israel, he witnessed a quarrel between the “Kolels”, the institutions that received and distributed the support money that was sent from the Diaspora, among the poor of the land. In 1866, with the participation of Reb Shmuel Salant (from 5639 he served as the rabbi of the Kolel for the Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem), he founded the “Committee of all Kolels” in Jerusalem, which was attended by the “Kolels” of various countries, and then peace prevailed.

The “open letter” that he sent to the philanthropist Sir Montefiore was widely publicized. In it, he spoke out against the slander that was spread about the settlement and proved the falsehood of the accusations, one of which was: “Among the residents of Jerusalem are people who did not come to work the land, but rather deserters who fled from Eastern European countries, having fled military service, since it is easy for them to travel on a steamship coming from the Russian Empire to the city of Jaffa”.

An interesting episode is Reb Meir Auerbach's attitude to the Hibbat Zion movement. After the “Eretz Israel Settlement Company” was founded in the city of Frankfurt on the Oder River in 5620, with the aim of establishing a large settlement in the Holy Land where the Israelites could engage in working the land, Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer and Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmacher joined it. Then came the appeal to the people of Jerusalem to support this idea. Reb Meir wrote a statement of approval for Rabbi Kalischer's book “Moznaim Lamishpat” (scales of justice), and in the journal “HaLevanon”, issue 3, from 5623, he in principle agreed with the actions initiated for the building of the land: the establishment of agricultural settlements; however, he has disapproved the renewal of sacrifices proposed by Rabbi Kalischer. The latter informed his allies that Rabbi Auerbach is sympathetic to the enterprise: “he almost agrees with our approach – unlike other rabbis”.

Rabbi Auerbach gathered young people from Jerusalem to his home and influenced them to go out and dedicate themselves to working the land. He encouraged them to go outside the walls of the Old City and establish settlements. With his assistance, the land on which the “Mea Shearim” neighborhood was established was purchased (in 5634), and he also participated in the construction of “Mishkenot Israel” and other neighborhoods.

One of his plans, related to the redemption of the land, was the “Company for the purchase of the land of Jericho”. After permission was given by the authorities and the purchase was about to be carried out – the negotiations stopped. At that time, the plan sparked a debate among the Haredim: Is it permissible to build the city on its ruins? The deniers relied on what is written in the Book of Joshua 6:26: “Cursed is the man before the Lord who rises and builds this city, Jericho; he shall lay its foundation with his firstborn, and set up its gates with his young child…”

[Page 214]

His disappointment at the cancellation of this purchase was great, and it shortened his life. He died in Jerusalem on the 5th of Iyar 5638. Before his death, he was privileged to see his students among the founders of the Petah Tikva colony.

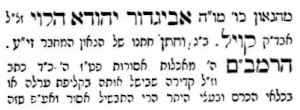

A page from Rabbi Meir Auerbach's book “Imrei Bina”

His book “Imeri Bina” earned him a name as a very astute scholar. In the questions and answers we find things for the rabbis in the Koło district and nearby cities, among them the Gaon Rabbi Israel Yehoshua Kutner. The last part of his book “Imeri Bina” was published in Warsaw in 5693, and was published by his grandson Rabbi Eliezer Auerbach, Av Beit Din of Lowicz, and contains sermons preached by Reb Meir. One of them is the sermon for “Shabbat HaGadol, which I preached in the holy congregation of Koło in the year 5610”. In this sermon he urges the townspeople to finish building the synagogue and to erect the new mikveh, since the old synagogue is about to be demolished.

In one of the chapters in his book “Imrei Bina” it is stated:

…And one day we will be privileged to see the rising of the Torah, our people, our inheritance, and our land. And the good God will comfort the widow's heart. The Lord will build Jerusalem, and will gather all the people of Israel wherever they are just like a shepherd does to his flock

[Page 215]

with his strength, to unite them together and return them to their land so they will be able to ascend the holy mountain and the temple. As a petition of a servant to the servants of God who bows before the holy mountain and the temple with weak knees and trembling feet and eyes full of tears, to a place where the gates of heaven are open. With many thanks for the past and a heart full of emotion and supplications for the future, that the Lord will enlighten our eyes”, etc.

Reb Leizer the son of Reb Gedaliah

To the memory of Reb Nathan z”l, the son of Rabbi Yosef Zeev, may God avenge him, and to my mother and teacher, Esther Chaya, may God avenge her, and to my dear brother, the child Mordechai, may God avenge him, who were killed for Kiddush Hashem.

In searching for biographical material on well-known rabbis who served in our city, one encounters many difficulties: the community registers, which could have served as a primary source, were lost during the Holocaust. The only remnants are the books that contain questions and answers or approvals, as well as books compiled by the rabbis of Koło.

In the lineage of generations, I found the first known rabbi from Koło to be Reb Leizer, the son of Reb Gedaliah. On Sunday, 28 of Marcheshvan 5552 (1802), he gave his approval to the book of the son of Rabbi Elazar, the son of Reb Shlomo Liser, and he calls him “the most excellent Torah scholar of the Rabbi and teacher Elazar of Kiryat Kalatshawi”. Reb Elazar composed a commentary entitled “Migdanot Elazar” to the book of Reb Yedahaya Hapinini. The approval of Reb Leizer, Av Beit Din of the holy congregation of Koło, is written in rhyme and in verse.

Reb Leizer was the son of Reb Gedaliah, Av Beit Din of the holy congregation of Copenhagen – how long was his way to head the rabbinate!

In searching for more details about him, I found the following entry in the new “Name of the great men of Walden”: “Reb Eliezer Leizer, a famous Gaon of his generation, Av Beit Din of Kalisz, lived in the days of the Gaon “Noda B'Yehuda” (Rabbi Yechezkel Landau). I assume that this entry refers to Reb Leizer, the son of Reb Gedaliah. Here are my reasons: I have not found another entry for a rabbi named Eliezer, also known as Leizer. The time of the Gaon Rabbi Yehezkel Landau corresponds to the time of Rabbi Gedaliah. There were also many connections with the city of Kalisz, and apparently rabbis moved from the rabbinate in Koło to Kalisz.

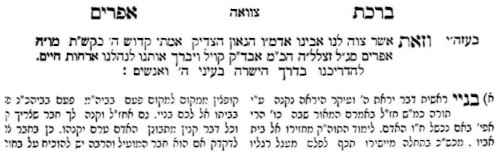

Reb Ephraim Segal of Koło and his son-in-law Reb Issachar, the author of “Pitchei Shearim”

The two names are mentioned together because their work in teaching Torah was done at the same time. After Reb Leizer, the Gaon Reb Ephraim Segal of Koło is mentioned. The beginning of his tenure in our city is unknown, but it can be assumed that in 5583[1] he was already serving in the rabbinate. The date of his death was the 14th of Tamuz, 5591. He was the grandson of the Gaon Reb Zelig Hanover and the son of the Gaon Reb Yosef-Chaim, Av Beit Din of Kalisz and Kreazmir, the son of the Gaon Reb Sender, Av Beit Din of Lesla. His composition “Birkat Ephraim” is a will to his sons. It was printed in his son-in-law's book “Pitchei Shearim”.

[Page 216]

Reb Issachar became famous as a prodigy at the age of twelve. It is said of him that he once went out to meet the Maggid of Kuznitz. On this occasion, he preached a wonderful sermon before him. The holy Maggid was so impressed by the young man's words that he ordered him to be brought to łowicz, to the Gaon Reb Chaim Auerbach, who headed the rabbinate there, and he spent six years there. After the death of his first wife, he married the daughter of Reb Ephraim Halevi Segal of Koło.

Reb Issachar wanted to live in our city, where he found scholars, and his father-in-law's house served as the house of the committee of sages. During the years of his stay in Koło, the reputation of the Torah rose and grew. Reb Ephraim's grandson writes in the introduction to the book “Petchei Shearim”: “The disciples of the Gaons of Koło rose higher and higher until they became great in the Torah themselves, taught and guided others and raised the Torah reputation in Koło to this day”.

Due to the royal decree, Reb Issachar left Koło and moved to Sompolno. There he “continued to spread his teachings even more vigorously in order to preserve the Torah – the path of the Tree of Life”. After the wrath of the decree subsided, he returned to Koło, connected with his former disciples and did amazing things with his perseverance. He engaged in Torah even though he lived in poverty and hardship. When his money was over, he accepted, on the advice of his teacher Reb Chaim Auerbach, the rabbinate in Częstochowa. From there he went to teach in Płońsk and later in Kowale and Stryków and again returned to Kowale and Częstochowa. He stayed in Częstochowa until 5612.

Reb Issachar fell ill with an eye disease and went to Breslau to be cured, where he died. His book “Pitchei Shearim” was published in two volumes, the first was published in the Sompolno in Częstochowa. He did not preface it with any “approvals”. Its contents: New halachas of “Sedrei Zeraim and Moed”, as well as questions and answers. He exchanged letters with Reb Avigdor Yehuda Halevi, Av Beit Din of Koło, and Reb Aharon of Koło.

Reb Issachar also wrote comments for Shas that were never published, and the Gaon Malbim was amazed when he read them.

[Page 217]

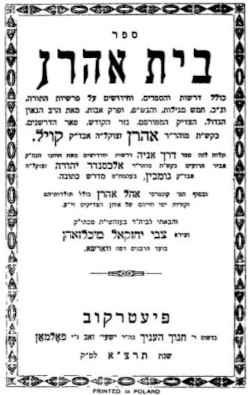

Reb Aharon Koyler, the author of “Beit Aharon”

Reb Aharon, the son of Rabbi Gershon Platzker, known as Reb Aharon Koyler, was born on Hoshanah Rabbah in 5557 and died on the 7th of Elul 5605. His son, Reb Ephraim Engelman, Av Beit Din of Kladow, and his great-grandson Reb Shlomo, Av Beit Din of Kladow – passed the manuscript of the composition “Beit Aharon” to Reb Zvi Yehezkel Mikhelzan in Warsaw, and he brought the book to print in 5691.

Reb Aharon was one of the most respected rabbis in the Koło congregation. His wife was a cloth seller, and this was their livelihood.

He was a humble and upright man. When he received his salary from the rabbinate, he did not check how much was being given to him. He would distribute most of his salary among the city's poor on the day he received it. For years and years, people in Poland spoke in his praise and considered him as a role model.

During his tenure at the rabbinate, the city was full of scholars. He founded “Talmud Torah”, the Mishnayot Society, the “Ein Yaakov” Society, and more. His lessons at the Shas Society were a regular occurrence throughout his tenure at the rabbinate. His memory surprised many – it was enough for him to review a book to forever remember its contents, and so the booksellers refused to give him a new book to review, lest he look at it once and never need it again.

[Page 218]

He was loved by the people and had no opponents at all. Reb Eliyahu Regaler, the Av Beit Din of Kalisz, came to visit him as he was dying. Upon his return to his city, he went to the cemetery, to the tent of the “Magen Avraham” and shouted in a loud voice: “Do you know, Master of the Universe, how much all his acquaintances love him, and do you know that I have one friend in Poland, the Tzaddik Reb Aharon, and you want to take him from me?”

The book “Beit Aharon” includes sermons for holidays and festivals, especially the days of Shabbat HaGadol. It also contains eulogies for great rabbis of the Torah, including Reb Chaim Urban of łowicz and Reb Akiva Eiger of Poznan. It also contains novellae on Torah Parashiyot, Tractate Avot, commentaries and a sermon on the five scrolls, and ends with a will to his sons filled with musar words.

The well-known Reb Nachum, who was the Av Beit Din of Sadek and spent the rest of his days in our country, wrote to Poland that he had seen a vision in is mind: The bed of a deceased person was being carried to the Western Wall. Everyone said that Rabbi of Koło was being carried to be buried in the Holy Land. It is true that Reb Aharon Koyler passed away. This story was narrated by Reb Ephraim Feivel of Safed, the son of the Rabbi of Kowale, who heard it from his friend, the Rabbi of Dąbrowa.

After the passing of Reb Aharon, the congregation sought to appoint his son, Rabbi Moshe Naftali. He served in the rabbinate for six years, but refused to be called rabbi and did not receive a prize. He was the son-in-law of the great Reb Hirsch Leib Frankel of Koło. From 5606 to 5615, Rabbi Meir Auerbach served in the rabbinate, about whom we discussed separately. In 5620, Reb David Kanfei Yona z”l was appointed as rabbi.

Reb David Kanfei Yona

Reb David, the son of Reb Mordechai Kanfei Yona, was born in Czechnow, and served in the rabbinate in Przasnysz, Płońsk, Kutno, and Krasnosielc. In 5620, after Reb Meir Auerbach left Koło and moved to Kalisz, he was appointed as a rabbi in Koło. He was a distinguished student of the Gaon Reb Shlomo Zalman of Warsaw, the author of “Hemdat Shlomo” and a friend of Reb Eliyahu Reiner of Kalisz. According to family tradition, the origin of the family is from the famous Sephardic Benbenisti family, as well as Reb Chaim Wittel. His mother was from the family of the great Gaon Reb Yaakov of Lissa (who formerly served as a rabbi in Kalisz), the author of “Beit Yaakov”, “Makor Chaim” and many others, he was one of the halachic and teaching Gaons of the late sixth century. Family tradition tells us that during his tenure in Kutno, in the year of the decree of 1825, he performed a miracle with a dove, and since then he has been called Kanfei Yona. In the Holy Ark, next to the Torah scrolls, manuscripts of his novellae in Shas and Poskim were kept; however, all of these writings were lost. I have not found any Responsa from him in many books of Responsa. Reb David zt”l died in Koło in 5627.

Reb Avigdor Yehuda of Koło

In 5634 he was still a rabbi in Blaschke (S. Nefesh Chaya). In 5641 he was a rabbi in Koło (based on a copy of a response I saw with Reb Chaim Elazar Alter

[Page 219]

in Jerusalem). Reb A.Y. was the son of Reb Raphael Zeev Leisht Lintel (HaLevi) and the grandson of Ephraim Koyler. He was well-known in his time, and many people turned to him with questions. Responsa from him were published in the book “Avnei Nezer” by the Gaon Rabbi Avraham of Sochaczew, in “Nefesh Chaya” by the Gaon Rabbi Eliezer Wax of Kalisz, and in “Yeshu'ot Malcho” by Reb Y. Kutner. The book “Abir HaRo'im” tells of his holiness, his ascetic life, and his involvement in the occult.

The Rebbe of Sochaczew publicized his greatness and righteousness, writing about him in a response in the book “Avnei Nezer”: “Peace and salvation to the honor of my soul's friend who clings to my heart, the famous Gaon and Rabbi, the righteous Hasid, the glory of the generation, the man you can't stop praising him, Avigdor Yehuda, may he live long life, Av Beit Din and Rosh Yeshiva of the holy congregation of Koło”.

And it is narrated by one of the disciples of Reb Chaim David, the son-in-law of Reb Avigdor Yehuda: One day Reb Chaim David traveled with his father-in-law, Reb Avigdor Yehuda, to a distant city and they passed through Krośniewice and stayed with Reb Avraham, the Rebbe of Sochaczew. Reb Avigdor Yehuda asked the shamash to enter Reb Avraham's room and ask if he was allowed to visit him. Reb Avraham announced that he would have to wait a while. This greatly angered Reb Chaim David. After a while, Reb Avraham opened the door and, while inviting the guests to enter his room, he apologized to them for their wait because he had to change his clothes in order to receive the distinguished guests in a dignified manner. Only then did the dayan's mind rest. After this, Reb Avraham turned to Reb Avigdor Yehuda and said to him: I know that your honor is knowledgeable not only in the revealed but also in the occult. I very much wanted to talk to him about the Zohar. They went outside the city, into the field and the forest, and discussed it for hours.

Reb Chaim David Zilber Margaliot

The last rabbi of our community was Reb Chaim David Zilber Margaliot. He was born in 5624 in the city of Żelechów, Lublin region. His father, Reb Naftali Zvi, was considered among the great Torah scholars in his time, and was a descendant of the Gaon, the author of “Tvu'ot Shor”. This family was related to the Gaon, the author of “Torat HaRam”, the rabbi of the city of Stanów.

From a young age, Reb Chaim David diligently studied Torah, devoting himself to it day and night. His excessive diligence aroused concern in his mother's heart. By the time he reached the age of mitzvot, he was already famous

[Page 220]

as a prodigy, he knew the Shas by heart. Every scholar who came to the city went to him to talk to him about Torah and marvel at his phenomenal memory.

Upon arriving to eighteen years old, Reb Chaim David married the daughter of the Gaon, Rabbi Avigdor Yehuda Levintel, the rabbi of Koło. The young man was promised a financial support for the rest of his life, so that after his marriage he could continue his studies. His devotion to Torah was so intense that for several weeks he did not leave his room, lest he be separated from his books even for a short moment.

When his father-in-law fell ill and saw that his end was approaching, he asked his son-in-law to travel to the elders of the generation to receive ordination to the rabbinate from them. Reb Chaim David went to Reb Yehoshua of Kutno and to the Rebbe Rabbi Avraham of Sochaczew, the author of “Avnei Nezer”, whom he greatly respected.

Rabbi Yehoshua, who had refrained from giving an ordination to young men, immediately recognized the greatness of the young man standing before him and accepted his application. Even the Gaon Reb Avraham was greatly amazed at the knowledge and sharpness of Reb Chaim David. He posed difficult questions to him and was amazed to hear his correct answers. Then the Rebbe, who was delighted with the young man, stood up and kissed the young man on the head.

Since then, sincere love has prevailed between the Rebbe and Reb Chaim David. The Rebbe would praise the young man from Koło before those who visited his home: He is like a wonderful cluster of grapes, no matter how much you squeeze it, it will not be emptied of its juice…

In 5653, before Reb Chaim David turned thirty, the Gaon Rabbi Avigdor Yehuda passed away. The people of Koło decided to appoint his son-in-law in his place. At first, Reb Chaim David was reluctant to hear this proposal, as he feared that the rabbinate position would interfere with his studies. Som the people of Koło went and collected letters from the great men of the generation, in which Reb Chaim David was asked to respond to the public's demand. Upon accepting the position in the rabbinate, he headed it courageously.

A heart-wrenching conflict broke out in the city when Rabbi Chaim David banned the slaughter of coarse animals due to the aggressiveness of the butchers. He feared that the shochets would be afraid of them and not act according to the halacha. In the presence of the butchers, he issued the ban at the slaughterhouse, and the city was in turmoil. The butchers and several homeowners formed a front against the aggressive rabbi. The slaughterhouse was locked for three years until a compromise was reached.

Reb Chaim David belonged to “Agudath Israel” and fought for his views with zeal. He was a member of the Council of Torah Scholars in Poland and opposed the idea of Zionism. On this issue he knew no compromise.

I heard from Mr. S. A. Tchorz: When Rabbi Y. L. Maimon visited in Koło in 1927, for the sake of raising funds for the “Keren Hayesod”, he wanted to give a speech in the Great Synagogue. The community leaders gave him permission without asking the rabbi, because it was believed that he would not allow it. However, Rabbi Maimon insisted that he go to the rabbi and ask for his permission. He spent a long hour with him. When he returned, he said that the rabbi had shown him manuscripts in which he expressed a deep love for Zion, but in his own way. He also permitted the Zionist speech in the Great Synagogue.

[Page 221]

Reb Chaim David spent most of his days in the Torah studies; from three to six in the afternoon, he devoted himself to the administration of the rabbinate. He spent several hours engaged in occult study. He devoted much of his time to writing his Torah novellae, and wrote many books that were not published and were lost during the Holocaust. Only one work, “Dover Yesharim”, in two parts, was published in Poland before World War II. A form can be found in the possession of his son Alexander Margaliot, who lives in Tel Aviv.

For nearly fifty years, Reb Chaim David headed the rabbinate in Koło. As he reached his prime, the terrible Holocaust struck Polish Jewry.

The elderly rabbi fled to Lublin, where his relatives gathered him. He tried to recover, but in vain – he fell ill with a serious illness and was unable to recover from it. He passed away on the 20th of Kislev, 5701. The Jews of Lublin buried him in the old cemetery in the city, among the graves of the great men of Israel.

Rabbi Meir Auerbach: “Imrei Bina” Jerusalem, Year of “BeHar Kodshecha”, Novellae for Orach Chaim and Yore Deah, First Edition. “Imrei Bina” Pietarkov Year 5660. Novellae for Orach Chaim and Yore Deah, Later Edition. Rabbi Meir Auerbach. “Imrei Bina”, sermons, Warsaw 5693. Reb Yitzhak Itzik Auerbach, book of Divrei Chaim on its four parts of Responsa. Reb Menachem Nathan Neta Auerbach, “Zechut Avot Veanaf Avot”, on Tractate Avot, Jerusalem, Year of Nechamat Zion. Reb Shimon Moshe Hanes, “Toldot HaPoskim”. Open letter to the Righteous Minister Sir Moshe Montefiore London 5635, HaLevanon Year 1, 5623, Issue 3. P. Grayevsky, Jerusalem register, Booklet 1. Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, “Moznaim Lamshitap”. Orach Ne'eman on Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim Jerusalem 5691. Encyclopedia Judaica, Berlin. Jervioh Enyclopedia

Rabbi Aharon of Koło. Beit Aharon Pietarkov 5691. Rabbi Issachar M. and Ohel Aharon Av Beit Din of Sompolno, Pinsk etc. “Pitchei Shearim”, New halachas of Sedrei Zeraim and Moed and Shabbat Kollel. Birkat Ephraim by Gaon Rabbi Ephraim of Koło, Bilguriya 5660. Rabbi Yedahaya, the son of Reb Avraham HaPinini with Bchinot Olam, Migdanot Elazar by Reb Elazar, the son of Reb Shlomo Zalman Isser, published by the Levin Epstein brothers, Jerusalem, 5614. Reb Alexander Yehuda (Reb Sender Leib) Midrash Ketubah on Tractate Ketubah Warsaw 5583. Responsorial Rabbi Akiva Eiger, 5649. Shaarei Toda, Monthly Rabbinical Collection (Figenbaum Warsaw, Part 6, Tevet 5672). Reb Avraham of Sochaczew, Avnei Nezer. Rabbi Yehoshua Kutner, Yeshuat Malcho. Reb Elazar Wax, Nefesh Chaya. Zvi Yehuda Mamalach, Abir HaRoim book, Pietarkov 5695.

Translator's footnote

By G. Wolkowicz

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

In the “HaTzfira” newspaper from 1897, a large article was published by a resident of our city, Zelig Brookstein, about the passing of Reb Shlomo Halevi Posner, and it opens with the following words: “With tears streaming down my eyes, I announce at the front page of “HaTzfira” the sad news of the death of the Tzaddik Gaon Reb Shlomo Posner, who died in Saturday night, on the night of Hosha'ana Raba, after a prolonged illness at the age of eighty-eight”.

I was privileged to see him in his later years, when I visited his home. I was a child at the time and I accepted my father's command to go to the revered man, who would test my knowledge of the weekly Parasha. The townspeople would often visit him, because the man was humble and his home was open to anyone.

This is how I saw him and this is how he was etched in my memory: a thin old man, withdrawn, sitting in an upholstered armchair, covered in white cloth. His hands rest on his knees and his face of a very old man shines with his kind eyes, expressing fatherhood and love.

The man's humility was expressed also by his appearance: he did not wear a fancy “shtreimel” and did not trim his beard and sideburns. His face was adorned with a beard that was not very prominent, his sideburns were short and the hat on his head was a black hat with a brim, the kind worn by ultra-Orthodox Jews. He sought to distance himself from anything that said: “Respect me!”

The townspeople sought his presence; they gathered at his doorstep to seek advice. In his conversation with them, he would emphasize in his words that he had acquired his advice and Torah from his teachers, one of whom was Reb Akiva Eiger, and the rest he had drawn from Chazal. He had nothing of his own, everything was from others. He would conclude his words with: “You too, look into the books and you will find what I told you, and perhaps more than that!” But the opinion of his admirers was not the same as his. They did find in him a wellspring of self-wisdom and said: “The apple does not fall far from the tree”, or: “As the rabbi, so does his disciple”#133;

We saw the great adoration for him on the eve of Rosh Hashanah: the heads of the congregation, the rabbi and the dayanim, went to his house to wish him a “happy new year”, followed by the dignitaries and the simple people. The most surprising thing was that in the long line of those who came to bless him were also Ger Hasidim, and Reb Shlomo was, as is well known, one of the opponents of the Rebbes.

Reb Shlomo Halevi was born in Poznan, a city in the western district of

[Page 223]

Poland. In his youth, he was educated and influenced by his distinguished teacher, the Gaon and Tzaddik Reb Akiva Eiger z”l, from the pillars of the Torah in the nineteenth century.

How did Reb Shlomo Halevi come to our city?

I have heard much about it from the elders, because they saved the details of his arrival to our city as if they were precious. While the Gaon Reb Akiva Eiger passed in Koło (he wondered through the surrounding cities, guided the confused, enlightened the eyes of Torah learners, and even made compromise between opponents), he met one of the city's dignitaries, Reb Yaakov Levi. He turned to him with a great request, asking the Rabbi to send him a groom for his daughter, one of his most distinguished young men.

Reb Akiva Eiger found the man to be upright and agreed to fulfill his request. About a week before Shavuot, he sent his disciple Shlomo to Reb Yaakov Levi and handed him a signed letter. Later, some of its contents were discovered in the cover of “Bat Rabim”: “I am sending his honor a Torah scroll for the holiday of receiving the Torah”.

The Torah scholars in the city wanted to examine Reb Slomo's character and found him to be very knowledgeable. In addition to his knowledge of the Rishonim and Acharonim, he was also blessed with wisdom and humility. Everyone was happy about the new resident, and most of all – the members of the Beit Midrash, they loved him with all their heart.

The young man Shlomo, who immediately earned the name “Rabbi Shlomo”, devoted his time after his marriage exclusively to the Torah, as was customary in those days. His father-in-law, Reb Yaakov Levi, took care of the young couple's livelihood and bought them a two-story house in the old market. He had enough money to live from the rent he received from his tenants. Several of the townspeople asked the young man to be a partner in their businesses. At first, he agreed to their request, but when he saw that the one who was busy with business had no time for Torah study and he is not available for public needs, he terminated the partnership.

Reb Shlomo devoted all his time to Torah. His “lesson” in the Beit Midrash attracted many, including outstanding scholars. Some of his students were not satisfied with the “lesson” and would come to his house, where he would add a special lesson for them. Happy were those who were privileged to do so.

The rabbi and the city's leaders approached him to accept the position of Rosh Yeshivah and said that his name alone would attract people from far away. This approach reveals to us how great the respect for him was, because there were great scholars in the city and they saw him as being far above them. Reb Shlomo refused and said: “What I learned I acquired from my teachers and friends, and who am I to be deserve to this authority?” And if you listen to my voice, we will establish a Shas Society and educate each other in Halacha”. With no choice, they reconciled with him and since then, his lessons in the Shas Society, which took place between Mincha and Maariv, have gained a reputation.

Reb Shlomo Halevi Posner had two sons and a daughter. His eldest son, Reb Avraham Levi, was appointed rabbi in the city of Zegrov; the second son settled in the nearby city of Konin; the daughter married Reb Yona Wilner, who was known in the city as the leader of the “Chovevei Zion”. He organized the first classes for studying the grammar of the Hebrew language, the first “courses” were carried out in the hall of the “Agudath Zion” society.

[Page 224]

The reporter concludes the article on the passing of Reb Shlomo Halevi Posner with these words:

“…From his house they carried him to the Beit Midrash, where the rabbi, the Gaon, Reb Chaim Zilber, delivered a eulogy for him, and from there they carried him to the cemetery, where his son, the Gaon, Rabbi Avraham Halevi, Av Beit Din of the holy congregation of Zegrov, gave a proper eulogy. After him, Reb Meshulam Kaufman delivered a lament, and all the people wept bitterly. The shops were closed. May God comfort all those who mourn him”.

The dayan, Reb Menachem Mendel Shubinsky, z”l

In the ranks of the humble and modest, the memory of our city resident Reb Menachem Mendel Shubinsky, a friend of the Tzaddik of Gostinyn, known as “Der Tehillim Yad”, should be mentioned. For more than thirty years, he served in the sanctuary in Koło. He was one of the pillars of the congregation, a man of charming appearance and a beautiful soul, well-versed in all the Talmud and Poskim, and also had knowledge in general culture. His action was not limited only to the Halacha; he was also a practical and organizing man.

He was humble all his life, but his reputation preceded him and reached far and wide. In 5640 (1878), a letter was sent to him signed by the leaders of the congregation of the city of Placz – an invitation and a request to him to accept the position of the head of the rabbinate, to inherit the throne of one of the great Torah scholars of that time.

Here are the words of the letter, which is kept by his grandson who lives in Ramat Gan:

Placz, the eve of Parashat Beshalach, 10th of Shvat 5640.

May God grant the request of the distinguished Rabbi Gaon, the precious man, the distinguished disciple, a teacher and a guide to the people, a man that one can't stop praising and glorifying, Moshe Mendel, may he live long life.The honorable Rabbi Gaon has no power to continue with the sacred holy work, after he led and guided the congregation for a long period, and he decided to end his tenure and appoint a younger person in this position. And thus, he said: I am too old to continue leading this congregation and bear the burdens and quarrels, so choose for yourselves a younger man who is dear to your heart.

Knowing his honor knowledge in the Talmud and Poskim and his ability to solve severe and light questions and to distinguish between the different halachas and between the different matters, we therefore said that God has chosen him to head the rabbinate and the Beid Din. Therefore, we, the overseers of the Placz, ask honor to inform us if he wishes to serve as the president and teacher of our congregation and what are the conditions that he will impose on us.

And we wish peace to him and to all those who are dear to him.

Reb Menachem Mendel Shubinsky did not respond to this invitation.

Reb Mendel Shubinsky was born in 5590 (1830) and died in 5654 (1894). His sons live in Israel and the United States.

| G. W. |

By Binyomin Shtern

Translated by Janie Respitz

The righteous man from Koło , Rabbi Shloyme Rotfeld was not referred to in town as “Rabbi” but as “The Good Jew”. Such a name suited him with a small addition: the beautiful Jew. His majestic splendid face, his entire demeanor, from head to toe possessed a lot of charm and drew attention. His pale face with his brown eyes, his wide flowing beard and curly sidelocks were engraved in memory. Always tidy, without the smallest stain on his clothes, as if he were a great pedant on his outward appearance. If outwardly he was like this, it was a sign that within he was pure.

On the street, when he would appear, he wore a lovely wide coat and, on his head, a shtreiml (a round hat edged with fur). He carried a walking stick with a sliver handle. At home he was also fastidious about his clothes: he was always wrapped in a brown silk dressing gown. He paced back and spoke, informally, to his Hasidim (followers). They often thought he was talking to himself, encouraging those present and himself.

On all complaints to God and to him on the part of those embittered and depressed, he would respond with mild, soft words. One had to have a heart of stone to oppose him. Worries would disappear, fears would vanish and a stone would be lifted from your heart. His glance really hypnotized and lured.

Reb Shloyme lived in the old marketplace, at Moishe Vroneh's, the fabric dealer. His apartment was “close to heaven”, on the third floor. Two of the rooms in his dwelling served as a House of Prayer, one for men and one for women. The other two, were for, may they be spared the evil eye, his large family.

He had few Hasidim, in total one hundred. Half were in Koło and the rest in the vicinity and across the ocean. The further away his Hasidim were, the more they respected him. They remembered him

[Page 226]

on holidays when the postmen brought him their gifts.

He was far from being provided with a livelihood. His means of support, barely, with great difficulty and debt somehow got him by, however, he was far from poverty. Once, a Hasid with “a long tongue”[1] askedd: “Rebbe, why do you not show us miracles?” He replied: “The fact that I support such a large family, may they be spared the evil eye, isn't that a miracle?”

Reb Shloyme did not make a fuss about himself. He did not turn over worlds nor engage in Jewish mysticism. He spoke with his Hasidim about everyday matters and his best teachings was the advice he offered. He had a clear head. Anyone who came to him once, remained his Hasid forever.

The Hasidim in Koło were simple people. I will list a few of them: Shmuel Stal (owner of a Bakery), Kharap, Avrom Yisroel Tchaynik (a buckwheat maker), the blind Yakov Tzorndorf, the brothers Mendl-Yakov and Shmuel Himl, Yekusiel Roznberg, Yisroel Tchaplitsky, Gotlibovsky, Mendl Arkovitch, Mendl Shtern, Wolf Kenig, Tuvyieh Vilfret. The last ones were his prayer leaders.

It was not difficult to visit Reb Shloyme. One did not have to send a petition to be a follower through the beadle as they did in the large Hasidic courts in Ger, Skernevitz and Alexander. If someone had a heavy heart, he would go straight the “Good Jew”. They would tell him everything from A to Z, not counting the words, trusting him as you would a good friend.

In 1934, after my father's death, I went up to see him. His friendly and good-natured welcome alleviated my pain. Before I had a chance to say anything he said: “You lost a father and I lost a Hasid (a follower), we are both mourners…

The most beautiful times with this “good Jew” were Sabbaths and holidays. There was so much joy and confidence. From where did he take this? His Hasidim gained strength and courage from this which helped them deal with the difficult week days.

His praying was a part of his splendor. Standing at the synagogue lectern as a community spokesman, he said the prayers clearly, as if he was talking to

[Page 227]

the Master of the Universe. His reading of Hebrew was fluid, stressing every blessing and plea. In many prayers he inserted heart, and many times, after praying he fainted.

Saturday night, at the third ritual meal, two bottles of beer were brought from the tavern keeper. The Hasidim took care of the food, especially Shmuel Stal. They drank the beer fairly, not distributed according to the sum which each one contributed. Some gave more and others gave less but everyone was treated as equal brothers. At the third ritual meal, they sang without stopping. They forgot and healed until late, even until midnight. That is when they prayed the evening prayer.

From the Sabbath one can learn what took place on holidays like Purim, Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot. On the high holidays the crowd was big. The “good Jew” was also different, in a higher spiritual world.

On the eve of the holidays, people sent the Rebbe gifts. The poorest of the poor did not skimp on a groschen and bought something to please Reb Shloyme. If a Hasid had a good “season” the Rebbe and his household would be satisfied as well.

Rarely did he go visit his Hasidim in the surrounding towns. Once a year he went to Tchekhotshinek to the baths. He did not have enough money to travel abroad.

The righteous Reb Shloyme had a large family. His eldest son, Moishele, had a sharp mind but was far from being a prodigy. The other children, youngsters. When I left, they were still small children.

The Rebbetzin, his wife, was a true helpmate. Without a maid, without financial means, she raised ten children. The house was always clean. You did no see worry on her face. She was a good friend to the wives of the Hasidim, providing a lot of comfort.

I will describe her: a small young married woman with a beautiful wig on her head, a cover for a religious Jewish woman. She was always pale, however her speech was determined and filled with confidence. Her neighbours were glad to know her because she tore down worlds in order to keep peace among them.

[Page 228]

More than Reb Shloyme needed his Hasidim, they needed him. When his Hasidim were expelled from town he went to Warsaw with his family. For a while he suffered in the ghetto[a] and perished in one of the gas chambers.

One of his sons was saved. During the war he went from Vilna to China and from there to America.

The last years in Koło were difficult and more than one “good Jew” was needed in order to hear a good word of comfort to alleviate the troubles.

|

|

| The monument built over the grave of the Rabbi from Koło

Picture by Sh. A. Shlezinger |

Original Footnote

Translator's Footnote

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Koło, Poland

Koło, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 25 Feb 2026 by OR