|

|

|

[Pages 25-28]

Zvi Wiernik

The history of the Jewish people is filled with suffering, tears and blood throughout its entire existence – beginning with Pharaoh, the ruler of Egypt, who enslaved the Jews, oppressed them, tortured them and ordered their [new–born] sons be cast into the river, through Haman the Evil, who plotted to kill and destroy them, the Spanish Inquisition, which burnt thousands at the stake, to the Ukrainian marauders Chmielnicki and Petlura, and the Arabs – with the Mufti Haj Amin alHusseini at their head, who perpetrated pogroms, robbed property and killed Jews.

But all along this blood–soaked path, never did the persecutions and killings reach the magnitude of the atrocities carried out by the Nazi regime, both in the number of victims and in the cruelty of the perpetrators, their systems and their actions.

Never was there, in the annals of Jewish martyrdom or in the history of any of the world's nations, such a genocide which was planned and conducted in cold blood and with elaborate technical methods that were calculated down to the smallest detail. Only in our generation did it happen that the mechanism of a large nation rose up against a peaceful, helpless population – men, women, elderly, children, infants and babes – to exterminate them by all kinds of unnatural deaths – starvation, shooting, hanging, beheading and strangulation – and all this in an absolutely horrifyingly systematic manner, while the rest of the world's nations stood silently by. Eight and a quarter million Jews lived in the European lands that the Nazis occupied. Six million of them were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators during the Holocaust. The People of Israel, which numbered 18 million in 1939, are now just 12.5 million.

This evil was also unprecedented in that this genocide, unparalleled in the history of mankind, was not perpetrated due to a spontaneous urge flaring up. It was not plotted by individuals, but by the villainous collaboration between thousands and tens of thousands, with and without uniforms, as well as organisations and squads whose only purpose and reason to exist was to carry out this vile mission.

The Holocaust in Poland

Polish Jewry, which numbered 3.5 million before the War, bore the heaviest brunt. Immediately when the Nazis invaded Poland, the terror and persecutions against Jews commenced, which were organised and managed by an agency that the Germans established solely for this purpose. It was headed by the nemesis Adolf Eichmann, who formulated and put into effect the annihilation of European Jewry. His agents were attached to all units of the German military and participated in the management of all the Nazi–occupied territories in the whole of Europe. Germans, of all social strata, took part in planning the war against the Jews. The jurists prepared “legal” grounds to strip Jews of their legal rights, to turn them into defenceless people whom it was permitted to humiliate, starve, rob of all their possessions, enslave and, finally, kill. Experts on psychological warfare exploited the difference of opinions within the local population in matters of religion [and] culture and ignited anti–Jewish sentiments. Their economists formulated plans on how to strip Jews of their property to the very last bit, including the hair and gold teeth of those killed. Intellectuals, artists, clerics, writers, journalists and radio presenters did all they could to justify the evil. The engineers designed the gaschambers and crematoria, whilst the medical “experts” trained on the corpses of the victims, mainly Jews. The concentration camps became colossal epicentres, where millions of victims waited in line to be killed, pondering on the smoke from the crematorium chimneys, which symbolised the end of suffering.

The chemists invented a special gas called “Zyklon”. A few boxes of “Zyklon” could suffocate thousands simultaneously! German industrialists efficiently drained the Jewish slave's last drop of sweat with twelve–hour working days of back–breaking, unpaid labour, in the course of which a person was transformed into a muselmann [walking skeleton] in a short time.

And the German army obeyed orders loyally. A genocide cannot take place without an army. No expulsion can be affected without its backing. They were the ones who destroyed the ghettos and wherever opposition sprung up – everything was turned to ashes. The ruins of the Warsaw, Częstochowa and many other ghettos bear violent and trustworthy testimony to this. This mighty mechanism rained its blows on the Jews of Europe and, in order to deceive their victims, they used various cunning subterfuges, spreading illusions to the very last moment.

In order to make their extermination task easier, they appointed autonomous Judenräte [Jewish Councils] in every ghetto and camp, which was meant to streamline the process of mass murder. These men naively thought that cooperation with the enemy would prevent calamities or perhaps weaken their power and, when they realised their bitter error, it was already too late.

The Jewish public did not accept the decrees that the Germans rained down on them and resisted, with its meagre means, to withstand the tempest. This resistance was manifested in all areas. Financially, despite all the decrees and the confiscation of Jewish property in industry and commerce, and despite the exclusion of Jews from all sources of existence and livelihood and their being crammed into ghettos, they fought for their [own] subsistence and also attended to the needy by establishing soup–kitchens, welfare institutions, hospitals. They waged a desperate war against epidemics. They saw to it that food and medication be brought inside the ghetto, selflessly and sacrificially – sometimes paying with human life.

Despite the prohibition to conduct schooling, the youth received private lessons – in courses which were organised clandestinely. Despite the synagogues having been closed down, prayer services were held – Jews worshipped in cellars and attics. There were secret libraries. The weapon of satire was deployed in the form of a monthly periodical, which denounced those who exploited their status and did not prove their social maturity. Organisations and political youth movements operated covertly and were in contact with all the Polish Resistance organisations. Despite the great terror and in defiance of the strict prohibition to leave the ghetto (the only punishment was death), dozens of youths left the ghetto in different manners, with all sorts of ploys. They travelled throughout Poland and were in live contact with the concentrations of Jews tortured in the ghettos of Warsaw, Łódź, Wilna, Kraków, Zagłębie and more.

The Holocaust in Częstochowa

[These youths] were the source of all the information inside the Częstochowa ghetto about what was happening in the cities of Poland – about the gradual annihilation of entire communities, the concentration camps in which people quickly became walking skeletons, the epidemics and hunger, the mass killings by shooting, gas–chambers and in gas–wagons [mobile gas–chambers in lorries] around Chełmno [and] about Oświęcim [Auschwitz] and Majdanek. Feverish activity ensued between all political parties to unite and defend the ghetto. The first operation was the raising of funds for the Leftist faction of the Polish Resistance. The news of the suicide of Czerniaków, who had been the head of the Warsaw Judenrat and had refused to give the Germans lists and aid them in the expulsion of tens of thousands of Jews from Warsaw to the Treblinka death camp, spread quickly in our city. The news of the ruin and destruction of the largest of the European Jewish communities proved that the Angel of Death was quickly approaching our city also. The Polish resistance was oblivious to our plight and people sought refuge. Some procured false certificates and travelled to work in Germany and other places as forced labourers, as Poles, or approached Polish acquaintances who, for money, promised to save them.

People gave babies up to convents or built bunkers in which to hide until the wrath had passed.

Those, who were unable to find refuge, obtained certificates from the Germans stating that they were useful professionals. Among all these, a small part nevertheless found courage in their souls and dared to rebel against the terrifying reality. Their operations and daring deeds are told in detail further on, in the “Resistance and Rebellion” section [of this book]. As we said, this was only a small part. Everybody else generally despaired – helplessness reigned supreme and the illusions that the Judenrat sowed were in vain. The murder machine was activated to its fullest ferocity the day after Yom Kippur in 1942, when about 35,000 men, women and children were sent to Treblinka. Around 1,000 were murdered at once and 6,000 were crammed into a few narrow streets, which were called the “Small Ghetto”. During the expulsion, some attacked Germans and Ukrainians, but they were killed on the spot. Some, before leaving their homes, ruined and destroyed everything, so as not to leave anything for the Germans. There were those who managed to escape from the railway carriages, to afterwards meet their deaths on the roads or those who arrived in Treblinka and were able to maintain contact with the ghetto from there. A few succeeded in escaping from there to the “Small Ghetto”. If anyone in the “Small Ghetto” had until then entertained any hopes at all regarding the fate of the deportees, now the bitter truth of the Germans' “Final Solution” became known – utter annihilation.

Szlojme Waga[1]

It was already clear, on the first day of the War, Friday 1st September 1939, that the Germans would occupy Częstochowa. With shocking strength, they faced the Polish troops that were diverted deep into the country.

The city's population was engulfed in an atmosphere of panic and began to follow the retreat of the army, leaving everything behind. The last trains and private automobiles, that went in the direction of Warsaw, Kielce and other cities, were full of people.

To escape, as far away as possible, was the only thought of the people who were filled with fear of the arriving Germans. On Friday, the first day of the War, thousands of peasants and their families from the surrounding villages marched through the city on foot and in wagons, with their cattle and with anything that they could take with them.

The highways and roads were so overflowing with wandering masses of people that the retreating Polish army had to make a great effort in order to break through a road for its further retreat.

Bloody Monday

On Monday, the fourth day of the War, the first German decree was issued – that all businesses should be opened immediately. The residents of the city began to move through the streets but, suddenly, the passers–by were shocked to see, with guns pointed, the Germans leading a large, heavily guarded group of people with their hands raised in the air.

Many of the people were half–naked. This image made a distressing impression on everyone, for it became clear that the terror was beginning. Two hours later, when I was at home, we heard shots that, each moment, grew increasingly stronger. And, even as we stood frozen with fear, we heard frantic knocks on our door and someone desperately crying, “Have mercy! Let us in!” We immediately opened the door and several Jews entered our residence and told us that the Germans were chasing people in the streets and shooting passers–by.

Before long, the Germans began breaking into private residences and driving everyone out. They did not pass our apartment by. Beating on our door with rifle butts, they demanded to be let in. When we opened the door, they stormed into the premises and ordered us to raise our hands and go outside.

We were hurriedly driven out to the courtyard, where we found some of our neighbours.

The Germans led us out into the street, where people were being pursued, as we had seen earlier. The streets were full of troops. Their weapons were aimed at us and, when our eyes met theirs, they laughed in our faces. When they noticed a Jew, they hit him over the head with a rifle butt.

Marching through the streets, we met other groups which were also being driven out of their homes. We were taken to a location where they began to sort us – men separately and women separately.

They counted out 200 people from our group and ordered us to proceed, with our hands in the air, to the Municipal Administration Building. When we arrived there, we noticed large diggings, which had been once intended as [air–raid] shelters, and German soldiers with machine guns next to them. Upon seeing us, one of them called out, “There they are, the dogs. They'll all be shot soon and thrown into these pits”.

An immense fear fell upon us. Due to exhaustion, we could no longer hold our hands in the air. They fell to rest on our heads. Barely moving our lips, we asked each other – Could these be our last minutes?! Some murmured silent prayers.

At this juncture, an occurrence, characteristic to those dramatic moments, took place. A Jew in his thirties, who was standing with us in the row, wet his trousers. One of the officers, noticing this, approached the man and asked him, “Why are you shaking, you swine? Now you're afraid. Why did you shoot at our troops?”

Hearing such words, we immediately realised what was happening, but our thoughts were interrupted when a Pole, who also stood with us in the row, suddenly called to the officer in broken German, “Cursed Jew, he is guilty, we are innocent.” However, the officer at once reassured him, “We'll soon be finished with the Jews”.

After holding us in a standing position under the burning sun for about two hours, ten military men emerged from the building and began to search each of us. Whoever was found with a razor, a pocket knife or any other sharp objects on his person, was forced to jump immediately into one of the pits, which were surrounded by soldiers who shot at the people in them.

If no sharp objects were found during the search, the man's fate hung with whoever had conducted the search, viz. whether he found him pleasing or not. The selection of people for death was done at such a pace, that queues of people awaiting their doom had already formed near the pits. Seeing the executions before their eyes, people tore their hair out and flung themselves to the ground, screaming in great desperation and crying out for help and salvation.

I stood in the group and awaited my turn to be searched. Some secret strength pushed me from the line. I went up to a German, who seemed to me to have more lenient glance. I unbuttoned my overcoat and emptied out the contents of the pockets – a pencil, a pen, a wallet, and a handkerchief and, giving everything to the German, I said to him, “See, I have nothing more with me. But I've left my old parents at home, and they cannot live without me.”

Meanwhile, new groups of people, from all parts of the city, were brought. They shared the fate of those before them.

Who knows how long the executions would have continued, had an air alarm and the immediate shooting at the Polish airplanes that appeared over the city not been heard. The Germans ordered everyone to lie on the ground, warning us that, if anyone moved from their spot or lifted up their head, they would immediately be shot. Their soldiers also got down on the ground with the muzzles of their guns pointed at us. We tried to bury our heads as deeply as possible in the soil and the shooting intensified. Bullets literally whizzed over our bodies and we were sure that we would not emerge alive.

Jews said, Shema Yisroel and recited Psalms. Christians also called to their saints for aid. All feared lest the Germans should hear their prayers and become upset.

When the shooting, which lasted a long time, had ceased, we were ordered to stand up and go to the horses' stables. But not everyone stood on their feet. There were casualties in our group.

Upon entering the stables, we fell exhausted on the horse manure and fell asleep, as the Germans locked the stables from the outside.

The mass execution that we had witnessed was not the only one in the city. Similar killings took place in all parts of the city, including the courtyard of the Jewish Crafts School at Garncarska 19. Murders of Częstochowa residents also took place in the churches, schools and in all public buildings and lots. They set fire to whole houses and burned them down with the tenants inside them, who were not allowed to leave. If someone tried to jump out of a window of a burning house, he was immediately shot. The Germans set up machine guns across the entire city and shot, without warning, at any Jew who appeared on the streets.

Thus transpired Bloody Monday in Częstochowa.

Original footnote:

Mojsze Konsens

When Hitler rose to power, we lived in the town of Praszka, on the Polish–German border.

My father, Leizer Konsens z”l, was headmaster of the local school and, by request of a wealthy farmowner named Sudowicz, we moved to live on the farm. This farm–owner persuaded my father that we should come live on the farm, even without paying rent, and my father accepted his proposal, so as to be able to learn agriculture, which would prepare him for Aliyah.

One Saturday afternoon, when I was in the farmyard, I suddenly saw a half–naked man running. This was a German Jew named Tischler, who had escaped from his home, at noon, because the S.S. bruisers wanted to kill him. This happened in 1934, when I was 9–years–old, but it has remained deeply etched into my memory. From then on, these types of incidents occurred frequently.

After some time, we moved from Praszka to Częstochowa, through the influence of Mr J. Goldsztajn, President of the Jewish Kehilla, who had known my father since childhood. Only once he had promised that we would emigrate to Palestine as soon as possible, did I accompany my father on his visit to Mr J. Goldsztajn, who used to hold the Third Shabbes Meal for several people, and I witnessed and heard everything that was going on in the city. On Saturdays, we prayed at the Ha'Mizrachi synagogue, on the First Aleja 10.

On Yom Kippur 1937–8, before Kol Nidrei, my father began his speech (“And Moses went up”), as if his heart had told him that the Holocaust on the Jews of Częstochowa would commence the day after Yom Kippur. With the onset of the Second World War in 1939, the Kehilla board of management began organising rescue and relief operations. Following the directives of Mr J. Goldsztajn, my father, A. Dancyger and a few other people, I became an emissary for good deeds, particularly to respected individuals, who did not agree to receive aid openly.

Once, when I rebelled against this system, my father admonished me and taught me a verse:

“Blessed is he that considereth[1] the poor: the Lord will deliver him in time of trouble.” [Psalm 41:2]. And, indeed, from the day after Yom Kippur 1942 – the day of Częstochowa Jewry's Holocaust – when I alone remained of my entire family, I felt an invisible hand saving me from all troubles. When I was 17, I was so debilitated and emaciated, that I looked 14 and, every time, there was a selection, I was the first to be taken out of the line. At the time the “Small Ghetto” was opened, I was taken one day to work at the Nowy Rynek [New Market], in a group of twenty people, under the supervision of a drunken German nicknamed Fessale [Yid.; “Little Barrel”], who shot his pistol right and left.

Our assignment was to move furniture, which had been removed from the Jewish houses, from one side to the other. We all had to load cupboards on our backs and carry them running to the other end. I once witnessed the sale of Jewish possessions at the churchyard, where a large queue of Poles stood pushing, with money at the ready, to buy Jewish property. A German stood there on a high platform, loudly announcing each item. The Poles, pushing and shoving each other, almost made this German fall down. He became enraged, and flung bowls, household objects and glassware at them to make them disperse – the commotion was great.

In the course of that same day, when we had finished our work, a head–count was conducted and the German suddenly realised there was one man too many in our group. He began counting again and, finding one too many, he decided to take one out. It fell to my lot to be chosen and the German took out his pistol and made ready to shoot me. At that moment, I remembered that I had a certificate in my pocket, which I had received two weeks prior. I showed him the document and he started counting again and calmed down.

On 4th January 1943, the Częstochowa ghetto rebellion broke out. When I heard the sound of the trumpet in the ghetto, I did not understand what was happening. I saw people going out to the ghetto square, so I went there to. A German stood at the entrance to the ghetto. He stopped me and asked me how old I was. I answered that I was 18. Upon hearing this, he ordered me to go up above the courtyard of the Polish Guard. I immediately realised I was in trouble again, because there were many people in the square and I was not put together with them. I ascended above the courtyard of the Guard and a horrifying image was revealed. Earlier, the Germans had already concentrated women, children and babies there. They had been caught in the bunkers, where they had somehow been able to hide until then. The women tore their hair and were hysterical and the babies wept bitterly.

There were women who kissed their children and there were women who strangled their children. It is impossible to set out such a scene on paper. In the meantime, other people arrived, all young, and among them was Fiszlowicz, with whom I was not yet acquainted. Among them was my friend Hajman, with whom I had studied at the vocational school. They huddled in a corner and my friend motioned to me to come nearer. When I came to him, he said, “We know where they're taking us and so we need to revolt. We've got one pistol and some knives and, if necessary, we'll even fight with sticks.”

Fiszlowicz began planning how and when to start the rebellion. Just then, we heard shouts, “Go down!” Polish policemen and Germans began driving us out with yells and blows.

We were around 70 individuals – twenty youngsters, the rest being women and children. Outside, in the square, some 3,000 people were already standing. Our group crouched next to them, and this was the last order Fiszlowicz was able to give us.

We stood there, heavily guarded by fifty Germans with bayoneted rifles. One German was commanded to take the numbers off our clothes. At that moment, a Jew began to escape from the group standing in the square. Some five Germans fell upon him with cudgels and bayonets to bring him back to our lines. In those instants, when the five bloodthirsty Germans launched themselves at the Jew, there was a stir among the lines. A commotion ensued and our group dispersed. The Germans were startled upon hearing Fiszlowicz's war–cry. Fear seized them and they did not notice me pushing my way out between two Germans. I sneaked out towards the houses which stood outside the ghetto and began fleeing among the abandoned houses. I ran, often falling because the snow was deep. I ran with all my strength, with shots ringing in the air.

Passing the houses, there was a snow–covered field. I ran without stopping until I suddenly heard shouts in Polish, “Stop, Jew!” I saw around twenty Polish youths chasing after me. I stopped, and turning around for the first time, I saw many Poles standing around the ghetto, laughing. The boys caught up to me and asked me, “Where are you fleeing to?” I understood their intentions and produced ten złoty. It was all I had. I told them that my money had already been seized earlier and they advised me to escape into the forest.

I began walking, not knowing to where. I was in shock and did not know where to turn, with a Jewish appearance and wearing wooden clogs. I wandered about on the three Aleje, among Poles and Germans, indifferent to whatever would happen to me. Then, I decided to go to my former workplace, a German military camp which was called the “Eastern Camp”. I stole into the army base, when a group of Jews passed through the courtyard carrying coal. I joined them and all knew, at once, that something had happened. Due to my traumatised state, I was unable to tell them anything. But, on our way back to the ghetto, we passed another group of Jews who were also returning from their work. They knew all about what had taken place in the ghetto. They told us that twenty people had been killed in the ghetto – among them, a young man named Sztal, with whom I lived in the same room, as well as my cousin's husband, Wygodzki.

The Germans, fearing a mass revolt, began ferreting about in the ghetto with detectives and informers. They discovered that a rebellion had, indeed, been planned.

One day, several houses on ulica Nadrzeczna were raided. Bunkers with weapons and ammunition were discovered there, as well as German clothes. Dozens were killed during this raid.

Translator's footnote:

Dawid Koniecpoler z”l

1st September 1939

The Polish army and police force have left the city. Panic reigns. Thousands of Jews have abandoned their homes and possessions and, taking only the bare necessities, began wandering. Hundreds of other Jews from the surrounding area have come to the city. Many people, young and old, are fleeing before the arrival of Hitler's murderers.

3re September 1939

Yesterday, on Shabbes, the first German military presence appeared in town. Today, larger groups of soldiers are already marching through. The Jewish population shows itself on the streets – naturally, [they are] very shocked.

4th September 1939

First thing in the morning, the word has spread that the Gestapo had arrived. Around eleven o'clock before noon, prolonged, violent shooting was heard throughout the city. It turns out that the Gestapo was shooting at the houses in different parts of town, driving the men out of their dwellings. Whoever is found on the streets is either shot, or taken to various assembly areas – in cloisters, factory premises or free spaces. Those concealing themselves must lie face down on the ground, with the shots whizzing above them. This continued until Wednesday, 6th September. In the afternoon, the first beaten and tortured people began to show up. This time, the Jews were equal in number to the non–Jews. Of the 400 victims, almost half were Jewish. Consequently, no Jews dared go out into the street anymore. If someone fell ill, they could not receive any medical assistance. If someone died, they were buried in their own yard. All the defensive trenches in town were full of dead Jews, Poles, horses and cattle. Many Jews were held under arrest and tortured at the former military barracks.

The Polish plebeians have immediately started looting Jewish property – shops are being ransacked and nor are Jewish dwellings spared.

They started at once dragging Jews from their homes to go work. Sadly, many never returned.

Erev Rosh Hashanah 1939

Mojsze Asz comes to my lodgings with a list in his hand. He tells me that, yesterday, the two Halachic authorities, Klajnplac and Grinfeld, as well as himself – Asz – as the rabbinate's secretary, have been arrested. They are being held in the cellars of Bank Handlowy [Commercial Bank], together with priests and others. Before daybreak, he had been summoned and given a list of six Jews which, by 3:00pm, he must bring to the Gestapo. These men were Leon Kopiński, Leib Bromberg, Natan Dawid Berliner, Dawid Koniecpoler, Józef Krauze and Juda Engel.

The first four are members of the Kehilla board of management. Krauze is a proprietor and Engel is an industrialist. He then added that, apart from Engel who had already been arrested, the other four had arranged to gather at the house of the Kehilla Secretary, Mr Wein.

At two o'clock sharp, we meet at Mr Wein's home. After brief deliberations, we decided that we do not have the right, at such a bitter period for the Jewish population, to refuse to come into contact with the authorities. With the question whether we would return alive tormenting each one of us, we all shook Mr Wein's hand who, mournfully weeping, accompanied us with his eyes from his wheelchair.

At three o'clock in the afternoon, we opened the door of the Bank Handlowy. The heavily–armed guard welcomed us with the words, “The dogs are here already”, and conducted us to a side–room, where three Gestapo officers sat at a table.

After certain formalities, one of them declared, “After what the Jews did to the German army in Częstochowa, we should really shoot you right now. But for that, we still have time”.

Instead, we are arrested. But, we are freed for two days, at the end of which we must present ourselves again. We were then given two minutes to decide among us who would be Chairman, Vice–Chairman and Treasurer.

At the end, the Gestapo officer said, “The Zionists will no longer need to apply for certificates to go to Palestine. In the Lublin region, the Germans will create a National Homeland where the Jews can devour each other.”

Second Day of Rosh Hashanah 1939

It becomes known that detained foreign Jews have been brought to the barracks in Zacisze. Through various channels, we have been able to put ourselves in contact with them. As it turns out, hundreds of Jews were captured on the roads. Among them are many Jews from Łódź, who were making their way to Warsaw on foot. Almost all were men. We provided them immediately, on Rosh Hashanah, with medical aid, which we acquired from Mr Neufeld. Later, we also assisted them with necessities. In this operation, Ms Cesza Kozak distinguished herself in particular.

For us Jews, unbearable times have come. We have been placed outside the law. Every German satrap has shot and tortured.

The six Jews, who were required to present themselves to the Gestapo at first every two and later every three days, have scrambled to establish free kitchens for the Jewish population.

The Old Synagogue, in which the renowned Częstochowa painter Professor Willenberg created his “Jewish style”, was barbarically destroyed by Polish hooligans right at the beginning, during the Ten Days of Repentance[1].

30th September 1939

Each day brings new evil decrees. Jews are not permitted to possess more than 100 złoty. All valuables, such as gold, jewellery, precious stones and the rest of the money, must be held in the specified banks. At the municipal offices, a temporary mayor has already been appointed. He is Częstochowa resident H. Belcke, a Volksdeutsch [ethnic German]. His attitude towards Jews has been arrogant and brutal.

Due to the persecution which the Jews have been subjected to by the Polish population, it was decided to send a delegation to Bishop Kubina.

Members of this delegation were Neufeld, Zeryker, Eng. Lewkowicz and Dr Szafier. During this visit, it emerged that Dr Kubina, himself, is also under house arrest.

A Judenrat is Elected

On the first weekday of the Sukkos festival [also on 30th September], Mr Kopiński was summoned to the Gestapo who notified him that a Council of Elders [Judenrat] with 24 members and himself as Chairman, was to be appointed immediately. That same day, a meeting was called at the offices of the Jewish Proprietors' Union, at Aleja 6, in which over 60 Jews participated – representatives of commercial and political organisations. The Judenrat, with 24 members, was then elected then.

15th December 1939

All Jews must wear a white arm–band, with a blue Star of David, on their left arm. No Jew is allowed to travel on the train or [use] any other means of communication.

24th December 1939

At seven o'clock in the evening, a fire breaks out in the New Synagogue's lovely building. Everything went up in smoke – all the Torah scrolls [and] the Judaic Institute's rich library next to the synagogue, which was founded by the synagogue's spiritual leader, Dr Ch.Z. Hirszberg. Simultaneously, a pogrom ensued on the Jewish streets, where Poles robbed Jewish belongings, smashed window–panes, etc.

January 1940

An inhuman night–raid – men and women were taken out and made to stand for some hours in the frost of the marketplace, after which they were conducted to the premises of a school in Zawodzie, where they were shamefully and barbarically tortured. The women were searched, in a “gynecological manner”, for gold. This operation was carried out by Ambaras, an officer of the gendarmerie, and his helpers. This same month, orders regarding forced labour for Jews were issued. Men between the ages of fourteen and sixty were enlisted. Jews, who had converted to Christianity, were considered as Jews. The Judenrat was required to present a certain quota of Jews for work every day, but this did not halt the capture of people for labour. Most times, the raids were conducted during the holidays, when Jews gathered together to pray.

The Year 1940

The Jews are robbed of their factories, shops and houses, which are placed into the hands of German “trustees”. Many Jews are taken to carry out difficult fortification works in the Lublin region. A great many of them die of hunger, typhus and the inhumane conditions.

The impoverishment of the Jewish population is on an unprecedented scale. The Judenrat's social welfare division gives out 10,000 free lunches daily.

The [now] homeless Jews, who had been driven out of Kraków, Płock, Bodzanów, etc., suffer the most horrifying conditions.

A certain number of Jews, from the Łódź ghetto, also came to Częstochowa. The homeless shelters, which were arranged in the houses of prayer and other large premises, presented a heartrending picture. In due course, a “Jewish Self–Government” was instituted – an independent civilian registry office, Jewish police, services for the maintenance of public order, Jewish courts of law, health services, victualling services, Jewish bread–ration cards, etc., etc.

The Scholastic System

The scholastic system for Jewish children is a chapter all on its own. Jews have their own schools, but these are clandestine. They were run at the beginning by Dr Mering and other teachers. With the return of Mr Anisfeld, the high school's headmaster, and some of the teachers, even high school courses are conducted.

In the area of medical care, wonders are truly being worked. In these difficult conditions, a great deal was done by “TAZ's” Mr Rozener and Dr Walberg, who was shot in June 1943 on the orders of the murderer Degenhardt.

The specially–created “Jewish Workers' Bureau” constituted a self–governing institution, whose aim was to regulate, in an organised manner, the dark law regarding forced labour.

9th April 1941 – the Ghetto is Instituted

On this day, the “Big Ghetto” was created. In theory, the ghetto encompassed all the territory from the railway bridge to the bridge over the Warta River. In reality, only the left side, which ended at ul. Kawia, the building at Aleja 14, ul. Wilsona, ul. Piłsudskiego and a part of ul. Strażacka St. remained outside the ghetto.

Jewish policeman were stationed at the various border–points. On the Aryan side, there were special signs in Polish and German, which read “Due to Contagious Diseases, Entry is Forbidden.” On the ghetto side, it read in German, Polish and Hebrew “For Leaving the Ghetto – the Death Penalty!”

It appeared as if the ghetto would be a Jewish self–government. But, in fact, it was the concentration of the Jewish population into one area, guarded by the Nazi bands of murderers, to facilitate bringing the plan of complete extermination to fruition.

24th December, 1941 – The Furs Akcja [Operation]

At the end of 1941, it was decreed that Jews were not allowed – on pain of death – to own or use fur garments, including children's clothing. Over the course of 48 hours, the Jews yielded up five wagonloads [of furs].

The Year 1942 – “Workshops” are Organised

With the assistance of Dr Michał Wajchert, Chairman of the Jewish Communal Self–Help [Żydowska Samopomoc Społeczna], the Judenrat set out to establish workshops, following the example of other cities. This was to enable Jews to work for the German military and, as a result, remain alive. In addition to the already existing fur workshops, mechanised workshops were created for carpenters, tailors, brush–makers, locksmiths, etc. The Jews were forced to pay the German authorities hefty sums of money for the workshops, which were concentrated in the former “Metalurgia” foundry, both for the permission to work and for the locales themselves.

Thus, several large factories were created in Częstochowa, in which hundreds of Jews toiled – as slaves, obviously. These were the Pelcery, Warta, Częstochowianka and Raków factories, which operated for the Hugo Schneider Leipzig–based munitions factory – “HASAG”.

22nd September 1942

The day after Yom Kippur, at three o'clock before dawn, the disaster began. All the street–lamps were lit, as the Nazis wished to carry out their mass murder in a festive manner.

Chief of the Schutzpolizei [Ger.; uniformed police force], the arch–murderer Degenhardt, killed forty thousand Jews in the first three weeks of this extermination campaign. The SS and the police leader of the Radom district, General [Dr Herbert] Böttcher and his aides, Obersturmführer [senior assault leader] [Hermann] Weinrich, Bornemann, [Walter] Blume and others, presided over the Nazi celebration.

During the Operation, Szmul Goldsztajn, who was Prezes of the Częstochowa Jewish Kehilla for eighteen years, an acclaimed Mizrachi activist who was involved with various Jewish institutions in Poland, in his prayer–shawl and phylacteries, attempted to throw himself from the second floor. But the killers noticed this and beat him in such a murderous fashion, that he surely did not make it to Treblinka alive.

The Jews were conducted to the train, driven with whips and gunstocks. Among them was also the elderly orthodox activist, Reb Icze Majer Krel. He walked barefoot but proud, with his head held high. He called out to the Jews, who had not yet been “selected”, who were standing facing the wall with their hands up, “Brothers and sisters! In the other world, I shall intercede for you before the Master of the Universe!”

Writers J.Ch. Zytnicki, A. Chaim Sziper, Zeligfeld and Blumenkranc were also killed in this period.

The Jewish Work Camp

In the city's oldest and filthiest quarter, by the river Warta, three streets were fenced in with barbed wire and, there, the work camp was established – the so–called “Small Ghetto” – for the officially remaining 5,000 Jews who were, in reality, 7,000.

Each and every resident of the camp was required, under pain of death, to work. At five in the morning, the camp was awoken and, at six, the columns of dismal Jews already stretched to their work places, escorted by special German work–guards. After twelve hours of work, often accompanied with whippings and beatings, they returned to their burrows.

20th March 1943

On Shabbes, the eve of Purim, 20th March 1943, Degenhardt – the arch–murderer of the Częstochowa Jewry – organised the infamous “Journey to Palestine”. The Judenrat, all the doctors and the rest of the intellectuals with their families gathered in a nearby house, outside the camp.

After marching a few minutes, they saw heavily–guarded vehicles already waiting for them. They were all taken out to the Jewish cemetery and, there, were shot. One–hundred–and–twenty–seven individuals perished then, including ten small children. The executions were carried out by the local Schutzpolizei men – Schott, Kulfisch, Passow, Schimmel, Onkelbach, Hantke and others.

25th June 1943 – the Work Camp is Liquidated

On Friday, 25th June 1943, at 4pm, police vans carrying the murderers drove up to the camp with lightning speed and surrounded it, terrorising all those remaining there with heavy shooting. A group of German policemen, led by their chief Degenhardt, immediately went to the underground tunnel into which they hurled a hail of grenades.

The fusillade continued for some hours and, as a result, dozens of Jewish victims fell. Jam–packed vehicles full of battered Jews drove away to execution. The Germans took weapons, money, uniforms of German units – everything that was there.

This attack was carried out with such surprising speed that the entire camp was paralysed and the killers freely ran amok.

26th June 1943

At seven in the morning, all men and women were forced to gather outside the camp. The murderer Degenhardt was already standing there, with his officers Roon, Werner, Zoppart and others. He conducted a selection and hundreds of Jews were taken to the cemetery, where they were shot. Those remaining were rounded up by the work–guards and conveyed to the local munitions factories. Over the course of those two days, over 800 Jews were murdered in Częstochowa.

28th June 1943

It appeared that with this, the liquidation was complete. But the Germans had not yet satiated themselves with Jewish blood. They surmised that there were surely more Jews hiding in the camp and, therefore, issued an “amnesty” proclamation for all who presented themselves on Monday, 28th June.

The result was a new mass burial of 200 women, children and elderly – those who would turn themselves in on Tuesday, 29th June. At five in the morning, they were shot in the cemetery.

Moving Graves

At the mass executions, the Jews were forced to strip naked and go to the open grave in pairs. There, they would be shot and would fall into the pit. Once the grave was full with martyrs and drenched in a stream of blood, the overlying layer of soil would swell up for a certain time, until all the blood had clotted.

20th July 1943

Once the demolition of all the houses in the camp was completed, the murderers conducted a new selection of Jews for the workplaces and, on that day, killed another 70 fresh victims, among whom were the Jewish policemen and their families.

Translator's footnote:

L. Bergman

The day following the occupation of Częstochowa, the Germans began capturing Jews on the streets for labour. As they were, as yet, unable to recognise a Jewish face well, they soon found Gentiles to help them with this. The Poles spoke no German, but they very soon knew the word “Jude”.

The first work which the Germans forced the Jews to do was to take beams on which thick boards were stacked and carry them outside. To carry such a beam outside, the Germans “gave” four people. Once it was out, they ordered only two men to continue carrying it. And finally, two men raised the beam and just one person was made to take it on his shoulders and continue carrying it by himself. The first victim was the son of the tailor Granek, from ul. Ogrodowa. Taking the beam upon his shoulders, he immediately collapsed under the immense weight and fell down in such a manner that the beam crushed him.

The tragic ending was that we went back home with one Jew less.

The First Mass Murder

On the morrow, the Germans brought upon us the tearfully, renowned “Bloody Monday”. At one in the afternoon, dozens of aeroplanes began circling the city, as if preparing for a great offensive. But suddenly, we heard wild shouting, “All men outside!” The German soldiers began savagely gathering together all the men on the street. The detainees were put in rows of five and were sent to different points.

The group, of which I was, was conducted to the foremost gardens by the municipal offices. At first, we did not know what the Germans were looking for, so we all threw away anything we had on our persons.

Behind the municipal offices, where the gaol once stood, deep pits had been dug. Machine–guns were positioned on the rooftops and, along the entire length of the Aleja, troops stood in full battle array, with helmets on their heads and armed with short rifles with fixed bayonets. The fingers were on the triggers, in readiness to shoot upon command. It seemed not like a city but – a battlefield.

Every 5–10 minutes, a vehicle arrived, packed full of people, and a bloody massacre ensued. Only a few were spared. All the others were shot on the spot.

As unpaid forced labour was one of the means which the German killers used to physically annihilate the Jewish population.

In the first days of the occupation, raids were conducted in the streets and any Jew, who chanced by, would be seized for different kinds of work, often unnecessary labour – simply to torment Jews. Dozens of Jews were shot during such “snatchings”. Many times, Jews were taken from their homes and, with blows and insults, were instructed to perform the worst and most difficult tasks.

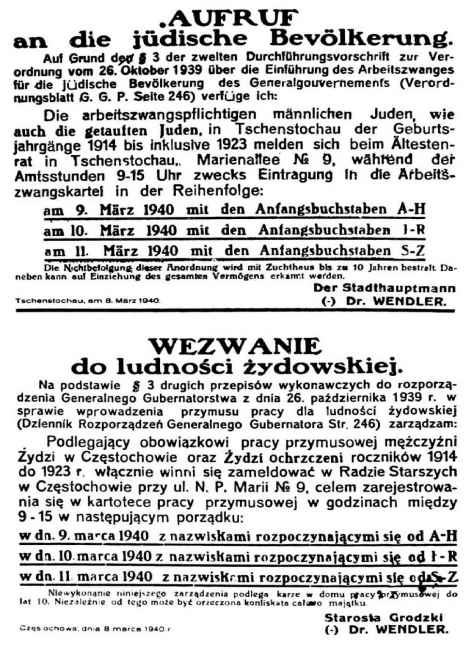

This chaotic mode of capturing people for forced labour later became “regulated”. On 26th October 1939, the Governor–General in Kraków issued a decree regarding the implementation of forced labour for the Jewish population and, in due course, similar regulations were published in all German–occupied cities.

On 9th March 1940, an “Announcement to the Jewish Population” appeared in Częstochowa streets, in which Stadthauptmann [City Captain; Mayor] Dr Wendler required all Jews (including converts to Christianity), born between 1914 and 1923, to register with the Judenrat.

On 2nd April 1940, a second command signed by Dr Wendler was issued instructing all those born between 1879 and 1925 to also be registered.

On 11th May 1940, another proclamation was issued from the Stadthauptmann, signed by Kodner, according to which, on 6th May, Jews began to be called to forced labour. Over the course of the two registration days, 8,330 men registered themselves.

[Translation, by Andrew Rajcher, of poster on next page]

|

To the Jewish Population Pursuant to Clause 3 of the second set of regulations implemented by order of the General Governor on 25th October 1939, in order to introduce forced labour for the Jewish population (Official Governor's Regulations p.246), I order that: Men, who are subject to forced labour, Jews in Częstochowa and Jews baptised between 1914 and 1923, should report to the Częstochowa Judenrat, at ul N. P. Maria [sic] No.9, in order to register in the forced labour file, between 9am and 3pm, in the following order:

On 10th March 1940 - with surnames beginning with I to R On 11th March 1940 - with surnames beginning with S to Z Failure to comply with this ordinance will be punishable by up to 10 years in a forced labour house. Notwithstanding this, the confiscation of all property may be imposed.

Grodzki Starost

Dr. WENDLER

Częstochowa, 8th March 1940.

|

|

Szlojme Waga

We knew that the German regime was taking over, for itself, private houses in the city. Tenants were being thrown out and various offices were being established there. In addition, the Germans were taking all Jewish residences, which the residents had left. The wealthy Jewish residences were looted – linen, furniture and everything left was taken. It was also known that one Jew, whom they had today thrown out of his apartment, had been ordered to create a representative group of several people who would give the orders of the German regime to the Jewish population.

Ten days had already passed since the Germans had entered the city – ten terrifying days and nights. The barracks were full of people. The battalions that arrive in town stop for 24 hours and continue on their way, apparently to the front. The soldiers stop near our windows and tease us. They point their guns at us. There are all sorts of types among them. One desired to start a conversation precisely regarding the “Aryan” blood that Jews allegedly consume, another about the wealth that the Jews had gained at the expense of the “Aryan” peoples, and similar themes. We attempted to conceal the long–bearded watchmaker from their eyes. However, one of the soldiers noticed him, and demanded that he come to the window. An argument about the Talmud ensued and he [the German] came very close to shooting a bullet through the window, because the Jew was unwilling to admit that he was familiar with the precept, “Kill [even] the best among the Gentiles.”

For several days, we were subjected to the devilries of one German who would come and pry all our windows open every morning at four, “so that the dogs should not sleep”, as he explained to the soldier on guard. He would then take a long pole and push anyone, who was still asleep, off the table [on which they slept].

German sadism was expressed in all its cunning. Ten men came to us, searched everyone from top to bottom, selected twenty of us and took them away, at which point the soldiers standing by the window informed us that we would never see our friends again! They would be shot, “because the Jews shot at our army in the city”.

We tried to convince ourselves that the soldiers, as usual, were just teasing in order to torment us. However, when several hours had passed and our friends had not returned, the soldiers' words began to drill into our brains. A father, who was there with a son who had been taken with the group, suffered terribly. He did not take his eyes off the door – perhaps the people would return.

There was a doctor [Dr Wider] with us, whose brother had been taken and, he too, was in deep despair.

As for ourselves, we went about the entire day tormented, silent – as mourners.

It was only at about eleven at night that we heard the sound of marching from afar and our hearts began beating intensively. The footsteps became clearer as they entered our corridor and, finally, the door opened and in came our friends! The father, who had been so worried for his son, was beside himself with joy, and the same with the doctor whose brother had returned. Indeed, we all breathed easier.

Our friends then told us what had happened to them.

When they were taken away in the morning, they were conveyed to a stall where each one received a spade with which to dig. They were then conducted through the city to the Christian cemetery, where they were put in a row and ordered to dig a large pit. This led them to suspect that they might be digging a grave for themselves. The soldiers stood over them and pressed them to work quickly and the Polish overseer measured the pit's depth from time to time. When the work was finished, they were made to stand in a row on the edge of the pit. Some broke down and began begging the Germans to spare their lives. The soldiers ordered them to be quiet and to stand straight. They stood this way for quite a long while, which seemed like an eternity, while the soldiers stood a short way off behind them, repeatedly cocking their guns. They also fired shots into the air, to increase the tension.

They then told our friends that this was the manner by which they would be shot, if anything bad happened to the Germans [in the city].

The Liquidation of Jewish Factories

The large Jewish factory “Gnaszyńska [Jutowa] Manufaktura” [“Gnaszyńska (Street) Jute Manufacture”], which belonged to Jews and employed several thousand people before the War, was located outside the city on the road to the German border. When the German military marched by the factory on the second day of the War, a high–ranking, long–time factory official went out to welcome the Germans with flowers. This official, who was known as a Pole for many years, was suddenly transformed into a Volksdeutsch [ethnic German] and was chosen by the Germans to head the factory.

Next to the factory were houses in which lived the master craftsmen, factory officials and the chief engineer, all Jewish. The new manager not only threw them out of their apartments, but no longer permitted them to work in the factory. Moreover, he also accused the chief engineer of stealing money from the factory's cash–box, for which he suffered such persecutions, that he was forced to leave the city.

Other factories, large and small, were stolen in a similar fashion from their Jewish owners and were put under the management of non–Jews, who were given the title “Treuhänder” (trustee).

This was also the case with factories that belonged to foreign owners, [such as] French, Belgians – countries which were at war with Germany. The “trustees”, taking over their offices, began their activities by checking if the original owners had left everything in “order” – whether the cash–box matched the books, if money had not been withdrawn from the banks and if the stock of raw materials and manufactured goods were in accord with the ledgers. If something appeared not to be in order, the Jewish owner was summoned to the “trustee's” office, where he was beaten murderously, after which he was taken to be interrogated.

Manufacturers, who had sent their goods elsewhere in order to safeguard them from the dangers of war, were forced by the new manager to bring them back to the factory at their own cost.

The majority of “trustees”, who had been formerly officials in the same factories where they were made managers, were even worse than their “foreign” counterparts.

No longer wishing to associate with the former owner and work colleagues of old, they laid off all the Jews from work and even hung up a sign at the entrance: “Entry is Forbidden to Jews” [Vor Juden ist der Eintritt Verboten].

A former official of the Jewish “Warta” factory was appointed its “trustee” – he had, at one time, been sent to London, at the factory's expense, to study the craft of weaving.

But this did not stand in good stead for them, for on the same day he took over the leadership of the factory, he immediately drove the Jews out. This same person also took over the linen factory, which he liquidated and then sold off all the goods and machines, thereby making millions.

The former Jewish director of the factory, who had remained without any means of support, asked him for aid. However, instead of offering his assistance, he stole his watch from him and mocked him.

The Germans also treated others in a similar fashion, both the owners of the factories and their Jewish employees, after they had robbed the rightful owners of their property.

The exceptions were smaller factories and shops, whose owners were professional workers and managed the businesses themselves. The “trustees”, themselves, were incapable of running the enterprises for they had been entrusted. Therefore, they retained the Jewish owners at their workplaces.

Working under such conditions was, of course, very embittering, but refusal to do so would be met with deportation to forced labour in the forests or by riversides, thus forcing them to stay put.

The wages of the Jewish workers, who were permitted to stay in their positions, were 25% lower than that which the non–Jewish workers earned. Furthermore, the non–Jewish workers at least received some few foodstuffs, while the Jews received nothing at all.

The factories continued operating, using the raw materials that the owners had left. A number of factories had enough raw materials for two years. Because the money [currency] that the Germans had introduced did not win the trust of the population, everyone rushed to spend it quickly and stock up on goods. Polish merchants paid any price for a little merchandise. The “trustees” of the factories were required to sell goods at pre–War prices, but they took ten times the price and listed the normal prices in their books, thus making millions.

The Jews, from whom the factories had been taken and who had not even been allowed to remain working there, appealed to the central government for support from the revenue of their former factories, having no other source of income. After a lengthy wait, the regime sent them to the “trustees” to receive 200 złoty a month, but with the stipulation that the support was to be paid out exclusively from the enterprise's “excess” income – if it had any – and under no circumstances from the capital.

The payment of these 200 złoty thus depended on the willingness, or lack thereof, of the “trustees,” who always found an excuse not to pay, although the sum was barely enough for three days' sustenance, under those conditions.

Over time, the raw materials which the former owners had accumulated were depleted and new material was supplied in very small quantities, almost inexistent, because most of the material was used for the production of munitions. As a result, the factories slowly ground to a halt. Post factum attempts were made by the Germans to consolidate various firms into one enterprise, but this too was to no avail. In the end, the factories were completely liquidated and the machines were sent to Germany and melted down for metal to be used for the war effort (artillery, shells, etc.).

The Seizure of Apartments

Not only were businesses and factories taken from the Jews, but their houses were also placed under a “trustee.” An office was created to this purpose, under the name of “The Trusteeship for Jewish Real Estate”. A specialist in housing management, who was for many years an administrator for Jewish home owners in Dortmund, was brought from Germany. This person immediately demanded that he be referred to as “Doctor”, and he settled down in great magnificence and luxury in the city, as did all the other members of the German ruling class. He demanded that a villa be put at his disposal, which the Judenrat was forced to beautifully furnish, and such was also the case in regards to his office, which contained numerous chambers.

His deputy and the rest of his office's personnel were Volksdeutsch as well as Poles from Poznań, who had always had a reputation for antisemitism. They were given control over entire streets of houses and began collecting rent. The Jewish homeowners had to pay rent just as every other tenant.

After the press had written that the houses were neglected and unfit, the tenants were forced to pay money for supposed renovations. But, in fact, the money was used for other necessities and the apartments deteriorated even further. From time to time, the “trustees” carried out searches in the Jewish residences and, at this “opportunity”, took anything of worth, on the pretext that it fell under requisition orders. In this manner, they took away small machines and goods etc.

They did this after the eight o'clock night curfew, when Jews were forbidden to be on the street and they could not see to how everything was being taken away.

Once, it happened that an audacious Jew, from whom everything had been taken, filed a complaint with the [Polish] police. The police's investigation confirmed his claim but, due to the fact that a Volksdeutsch was involved, the police did not have the authority to continue attending to the case and referred it to the Gestapo.

After a few days, the Jew and his son were summoned to the Gestapo. However, contrary to their expectations, viz. that their complaint would be looked into, they were welcomed with a savage beating and made to stand before the administrator who had robbed them, while the Gestapo officer reprimanded them, saying “Jewish swindlers may not accuse persons of the German People – under any circumstances.”

Only with great difficulties was it possible to extract the two Jews from the Gestapo. This was a lesson for all of the Jews – that they were not to complain against a German or Volksdeutsch, regardless of what their crime may have been.

Chaim Szymonowicz

|

Relations between the Poles and Jews in Częstochowa, in the last years before the War, were quite stressed. The Christians quite simply said, “Wait, wait, Hitler will come and show you already”.

For a few years already, the Jews did not go to any parks and, particularly late at night, it was terrifying to go out on the street. It was often heard that, here and there, a Jew had been stabbed. Flatt was stabbed, in broad daylight, on his way to work.

It was in this pogrom–like atmosphere that the War broke out.

On Friday, 1st September, at five o'clock before dawn, German aeroplanes were already flying over Częstochowa. That same evening, the Polish army retreated and approaching Jewish soldiers reported that the Germans were marching forward with great forces. Upon hearing the tragic tidings, more than half the city's Jews began walking and travelling to Mstów. Many of them then returned and those who were on the roads were shot by the German planes. Dozens of victims fell in this manner.

The Germans entered Częstochowa on a Sunday (the third day of the War) and, already on the morrow, they perpetrated the “Bloody Monday” [massacre]. Leibel Kac was shot in the Nowy Rynek. In the evening, all [sic] the Jews were herded into the cloisters and shot from behind. I, myself, was in the church in the Nowy Rynek. Next to me, on the floor, sat Reb Awigdor's son, Jakób–Icek. He hid his head, so as not to see the Christian religious paraphernalia.

The following day, we were taken to the barracks of the 27th Regiment, where we were held till Thursday under inhuman conditions. Leaving the barracks, we passed through the square and saw a hound chasing down Szyja “Tzimmes”, tearing live flesh from him. This made a horrifying impression on us – the Germans looked on and laughed.

“Sisyphean”[1] Labour

Then men and women began to be captured for work – not for any productive work, but just to torment and humiliate. Thus, for instance, we carried bricks all day long from one place to another and then back in the Town Hall Square. Such was also the case for a group of youths, who were sent to Przyrów to supposedly “regulate water” [divert the course of a river]. But, in truth, this was all just to torment them – to break the people's morale.

In September 1940, the Judenrat was ordered to present a few hundred men to be sent away to carry out a job. No one knew where.

Notices were sent to unemployed youths and I, also, found myself among them. On the morrow, we were conducted, under a heavy guard, to the train and thrown into the freight wagons. In the morning, we arrived in a concentration camp in Lublin, from where the Germans sent us to perform a task.

We walked some 30 kilometres on foot to this work and, to further embitter our lives, to our group, they added a couple of elderly Jews who hadn't the strength to make even one step. Those who stopped on the road were beaten. Many fell from exhaustion.

In Bełżec

After marching an entire day, we arrived in Bełżec. There, we were let into a large square among gypsies, under the open skies. The whole night, a torrential rain poured down and we clung to each other because of the cold and wet. In the morning, we walked on and arrived in Cieszanów. Here, a new chapter of torture began. We walked several kilometres to work every day, escorted by Ukrainian bandits who beat us murderously.

For Kol Nidrei, everyone assembled at the synagogue, which was within the camp, and Srebrnik from Częstochowa, with a heavy heart, recited Kol Nidrei.

Our plight in Cieszanów became known in Częstochowa and the Judenrat sent out a delegate, Mr Bromberg. He came to us and was unable to utter a single word. The tears choked him, seeing our misery. Sorrowfully, his Jewish heart did not hold out for long.

On our journey homewards, we were made disembark for another couple of days of labour in Bełżec. Mostly Jews from Lublin worked there – elderly Jews with long, white beards. The Germans intentionally gave the older Jews the heaviest tasks. They stood in water to their beards. It sent a shudder through one to look at them.

After nine weeks of hard labour, we returned home, physically and mentally broken.

The “Big Ghetto”

In 1941, the “Big Ghetto” was set up in a small area, into which were driven the more than 45,000 Jews from Częstochowa, including newcomers. At once, they ordered all Jews to wear the Star of David symbol and we were not allowed outside the ghetto.

The first victim apprehended by the Germans outside the ghetto was Mojsze Janowicz, a son of the leather–merchant in the Stary Rynek (in Bajgele's building). At the Town Hall Square, a German ordered him to run home and, as he did so, he shot him from behind. This was a warning to the Jews to not go far from the ghetto.

In the summer of 1942, news began reaching us from other cities, that the Germans were liquidating the ghettos and sending the Jews to death camps. The people of Częstochowa fooled themselves with the illusion that this would not happen in our city, because the Germans had set up factories and they would need workers. But the tearful reality nullified all hopes.

On Rosh Hashana 1942, German soldiers burst into the synagogues and began murderously beating the worshippers. On Yom Kippur, we no longer gathered, but prayed silently in small groups. At eleven o'clock, word spread that the ghetto was being surrounded by the Ukrainians with the black caps and, by the close of Yom Kippur, we already knew that the liquidation of the ghetto was beginning.

Later, the “Small Ghetto” was set up in Częstochowa. The borders were on ul. Mostowa (the side of Gittel Esterl), ul. Senatorska (Majer Biczner's side), to the gubernia [seat of government?] and the Warta River, from the “crates” to Polak's building. The “Small Ghetto” was, in truth, a labour–camp, to which the people from most of the workplaces came to sleep.

On Erev Purim, 1943, a notice was published that the intelligentsia were to present themselves, supposedly to travel to Palestine. But they were all taken to the cemetery and shot there. Dr Bresler, who was from Płock, was delayed with a patient, thus being saved from certain death. His wife, née Nowak, jumped from the moving vehicle midway there and was also saved. Kurland also saved himself by jumping off. Before long, the “Small Ghetto” too was liquidated. The young people were sent to “HASAG”, whilst the older – to the death camps.

Editor's note:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Czestochowa, Poland

Czestochowa, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Apr 2020 by JH