[Page 2 - English] [Page 3 - Hebrew]

A Man's Fate

Elimelech Shklar

The town of Zuromin, situated in the northern corner of the Mazowian Province in central Poland, was first mentioned in the eleventh century. Graves from this period were discovered near Poniatowo and consequently the area became known. The forested terrain attracted fowl and other wildlife, which flocked to the area in search of food. The name Zuromin is derived from the root zher, meaning food.

In 1767 the land was awarded to Andzej Zamoiski. He established a church in the small township. At the time, the entire population numbered 312 inhabitants, who dwelled in 52 homes. In 1794, the same year that Poland was divided for the second time, a major fire broke out in the town and destroyed 44 homes. By 1811 the population had grown to 719 inhabitants but was still without a single Jewish family. Only in the year 1819 did 21 Jews settle in the town (the total population by this time had increased to 859 people). At this point there were 110 homes in Zuromin, two of which were brick houses. By 1826 the Jewish population had increased to 276 residents. During the rebellion against Russia in January 1863, Jewish settlers played an active role in the battles in the villages of Poniatowo and Osokwa. Among those who fell in this battle was a Jew, Shmuel Pozner.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Zuromin boasted three streets and a synagogue. In 1905 there were nine local bakers. In 1919 an elementary school was founded, with Mr. Brodetzki as principal. The pupils were all Jewish girls. In 1923 Christian students were added to the roster. There were two Jewish female teachers, Zidovna and Thelimovna. There was also a music teacher, Gralewski, and Kasian the Armenian. The nearest cities with significant Jewish populations, Mlawa, Sierpc, and Rypin, were 30 kilometers away. In spite of this distance, the area, which consisted of many small villages, attracted craftsmen and shopkeepers from the environs and, as such, it was possible to make a living from the local population. Unfortunately, there are no existing Jewish records from this early period. It was only towards the end of the nineteenth century that the Jewish population increased to a point that necessitated the establishment of a local Jewish cemetery. Prior to this, the Jews were buried in the village of Kidzbark, which existed as a Jewish center before Zuromin.

The Jewish population of Zuromin drifted in two distinct directions as a result of the ongoing cultural development – to the Zionist resurgence on the one hand, and to the activities of the Bund on the other. The Bund played a pivotal role in the education of the underprivileged youth and its supporters, and the organization of workers fighting social oppression emerged from their ranks. The more educated youth aligned itself with the Zionists, founding the movements HaShomer HaTzair, HaShomer HaLeumi, and the rightist and leftist wings of Poalei Tzion.

In 1912 Mr. Yitzchak Skorupa moved to Zuromin. He was affectionately known by his nickname, “The Hebrew Teacher.” This man made his mark with the local youth who studied at his school and who knew him from the Zionist movement. The school produced an impressive number of students well versed in both general and Judaic studies.

The Bund activists established a library named after Y.L. Peretz, and due to widespread poverty among the Jews, many youths began turning toward communism. Although the underground movement was practically inactive, it directed its energies towards founding a large library with many select titles. The books were purchased with funds collected from amateur theatrical productions and other cultural projects. The Zionist organization's main activity was the preparation of youth for aliya to Israel, and every year special summer camps were organized. Many chalutzim (pioneers) left their homes and traveled to all corners of Poland to prepare themselves for their eventual move to Israel. They waited for official approval to make aliya.

During this period there was a dramatic decline in Zuromin's quality of life. There was no cinema, no sporting events, not even electricity or radio. By 1926 Zuromin had become a city of 5,000 inhabitants, 40% of whom were Jews living in the town's center. At the time, the town's electricity was supplied by a flour mill. The owner was known to have been very ill. Since he did not maintain the machines as necessary, they eventually broke down. In 1935 the town returned to the “Dark Ages” as it was left with no source of electricity. Three oil lamps lit the town's streets.

During the same year, after graduating from elementary school and completing cheder studies with Mr. Skorupa, I traveled to the city of Grudziądz in western Poland to visit my uncle. While walking down the street, we noticed that we had arrived at the technological school building. I applied and was accepted to the school, after having received high scores on the entrance exams. I was the school's sole Jewish student. The principal of the school, a Jew who had converted to Christianity, couldn't understand why a Jewish boy would want to learn a profession so uncommon among Jews. When he inquired as to my native tongue, I responded, “Hebrew.” He was duly impressed, although in actuality we spoke Yiddish at home.

The subsequent period of studies was arduous, in part because of my economic situation and in part because of the rampant anti-Semitism that erupted after the death of the Polish leader Pilsudski. A typical occurrence took place one winter day during religious studies (from which I was officially excused); classmates asked me to attend the class so they could turn me into a Christian like themselves. They knew that I was fluent in Hebrew and told their priest that I spoke the same language as Jesus. The priest asked if indeed I spoke Hebrew, and I replied, “Jesus spoke Aramaic not Hebrew.” The priest was astounded and asked if I knew Aramaic. I answered by reciting the prayer Yakum Porkan Min Shamaya. Of course, the class continued with a minimal amount of discipline. But the affair didn't end here. In our next class the metallurgy teacher was having difficulty controlling the unruly students. In desperation he shouted, “Quiet! You think this is a Jewish cheder?” Since I am a proud Jew by nature I indignantly stood up and said: “Mr. Engineer, I studied in a Jewish cheder, and for your information there was more order and discipline there than in your religious-studies class!” The class's reaction was quite predictable. Almost every morning on my way to class I was greeted with curses and flying objects. My happiest memories during those years were the days when I went back home to my town for summer vacation.

After Pilsudski's death and the subsequent rise of anti-Semitism, the economic situation worsened. Many families lost their savings. Several girls from well-to-do families were forced to relocate to Warsaw in order to work as housekeepers and nannies. During the last years prior to the outbreak of World War II, Zuromin's Jewish community suffered immensely. The government disseminated anti-Semitic propaganda and banned Jewish merchants and tradesmen from working. Only a select few received aliya certificates or managed to immigrate to Latin America.

After graduating trade school in Grudziądz, I was unable to find employment because I was Jewish. In contrast, my classmates were promised jobs two years before they even finished their studies! This reality prompted me to borrow a small sum of money from my cousin Mirel. I then set out for Warsaw to find a job. The year was 1938, just after the Sukkot holiday. Since I was unfamiliar with the city, the first thing I did was to purchase a map. Next, I went to the main post office and checked through the local phone book for addresses of metal-processing companies. Each day I planned an eight-to-ten-hour walking route around the city because I couldn't afford to pay bus fare. After five exhausting weeks, I finally found a job. Unfortunately, the pay was one-third of an average salary. It was a difficult time for me. Still, in spite of my low wages, I was proud that I was able to support myself.

1939. Hitler exerted political pressure on Poland, which ultimately led to the outbreak of World War II. It is hard to describe the extent of hunger and suffering in the besieged city, the fear of death aroused by the sight of thousands of dead bodies. On Rosh Hashana the Germans sent out fliers to the city's Jewish center declaring: “For you Jews, we are preparing a special New Year's celebration.” On the eve of the holiday the Germans bombed Warsaw. The Jewish quarter was especially hard hit. Many residents were killed in this attack. On Yom Kippur once again they bombed the Jewish center. After two days, Warsaw surrendered. Imprinted in my memory is the picture of the German army marching through the capital of “independent” Poland.

Since Zuromin wasn't situated near a main thoroughfare or railway line, it was not severely affected by combat activities. Goldack's son David was Zuromin's first casualty, but his death resulted from his rush to escape from the town. Hunger and the critical food shortage were the main factors in my decision to leave Warsaw. Thanks to my Aryan appearance, my mission was successful in spite of the German guards and the Polish police I encountered on the way. After walking for over 100 kilometers, I finally reached Zuromin on Simchat Torah. This day was more reminiscent of Tisha B'Av because the previous day the synagogue had been burned.

As soon as the German police established a foothold in the town, it instituted a wide range of anti-Jewish measures: not allowing Jews to walk on the sidewalks, forcing them to wear patches bearing the word “Jew,” forcing them to pay a special tax called “a contribution,” and so forth. After the third payment, the Germans decided to deport the Jews. This was carried out on November 8, 1939. However, prior to the deportation, the Germans sent several hundred youth (I was among them) to forced labor in several estates in Pomerania. Every day we had to pick potatoes, but we received insufficient food in return for our work. After picking all the potatoes, we were released and forced to walk home on foot, quite a considerable distance. That night, the majority of Zuromin's Jews were taken from their homes and brought to the municipal lecture hall. The Germans began their search for silver, gold and jewels. The search was carried out with rough physical handling resulting in numerous injuries, mainly among the women. By daybreak, the Jews were deported to an area adjacent to Sierpc, the railway station. They passed through the street where I lived with my family. The sight of the deportation reminded me of Hirshberg's painting The Driven. The cries of terror, the voices of those calling out the names of children and parents, searching for each other in the darkness – this scene caused me to break into tears.

At that moment I decided that our family must also join the deported. My rationale was that this move would prevent future suffering – we wouldn't be caught in the search for relatives. I remained close to home because we still couldn't believe that the entire Jewish community would be deported. We were convinced that the Germans would simply allow the Poles to rob and loot Jewish property and then let the Jews return. This is not what ensued. That day I discovered that several Jews had remained in town, but they were required to appear before the Germans to be searched and then deported. I decided to also leave and join the deportees, who by this time were already outside the town's limits. My provisions for the trip were a loaf of bread and an old bottle of wine, prepared years before by my mother's aunt Gela Rakower. The wine was fermented at the time of the birth of Gela's granddaughter Ferka and put away in storage until her wedding date (a celebration which, most unfortunately, never took place). I was not about to leave this special wine for Israel's enemies. While we were walking, I shared the wine with Avraham Zilberstein; we finished every last drop. I saved the bottle and filled it with spring water, to be used during times of need. Indeed, shortly after the Germans loaded us into closed railway cars, they began pushing around several youngsters, one of whom was Motek, the son of Shlomo Krata. The crowded conditions made us all very thirsty, and I decided that this was the time to pass around my water bottle to the children and pregnant women. I achieved another mitzvah by giving Yoab Garfunkel an injection when he fell ill.

Our first stopover was at the town of Pomiechuvek located not far from Nowy Dwor, near Warsaw. We were “greeted” by a new calgasi (division) of the Reich's troops. Once again we were searched for silver and gold and severely abused. We then crossed a temporary bridge across the Bog and arrived in Nowy Dwor, which was under the jurisdiction of the Polish General Government. This was an autonomous area and it was here that the Germans assembled most of Polish Jewry. The majority of Zuromin's Jews were then transferred to Warsaw. This was the beginning of a terrible period of cold, hunger and poverty for all of the Jews who had no choice other than to stay in Warsaw's synagogues.

The synagogues took responsibility for the absorption of the destitute. This accounted for 95% of the Jews in Warsaw. They were unable to find alternative housing in the already densely populated Jewish community. Bitter was the fate of these refugees. I recall a horrible sight. Once, when walking down the street, I met Ber Rizowy, a former wealthy wheat merchant from our town. He was heading down Muranowska Street with a wooden tray tied around his neck. Displayed on the tray were shoelaces, shoe polish and notions – all for sale. I turned my head the other way so as not to embarrass him. The troubles were endless, The Germans chased the Jewish youth in the streets. Once, the Germans ran after a boy named Chanoch, the son of Isacher Fridenberg but Chanoch managed to escape to his home. The Germans caught up with him and shot him in front of his entire family.

The Germans began worsening our lot in a systematic fashion. Most difficult was when they began rounding up Jewish children in the streets and sending them to work camps in the east. After witnessing this with my own eyes, I resolved to take fate into my hands. At the end of 1940 I decided to leave my parents since, in any event, I was unable to help them. I planned to return to Mlawa, near Zuromin, in order to salvage some items and then transfer them back to Warsaw.

By this point it was already quite risky and expensive to leave the Warsaw Ghetto, but I had no other option. I had to devise my own system of escape. The Poles were still allowed to travel by streetcar through the ghetto – under police guard. I decided to hop on the last car as it swerved around on Nowiniarska Street. The policeman, who luckily was stationed in the first car, didn't notice me. I had an empty sack under my arm, so I could pass for a Polish smuggler who was returning after smuggling his goods into the ghetto. Indeed, the Poles looked upon me with wonderment and contempt, but my Aryan features kept them from suspecting that I was Jewish. The worst they could have possibly thought was that I was providing services for the Jews.

During the train ride from Mlawa to Pomiczowek, (a border station between the Reich and General Government) I risked my life several times. I passed through the Narew marshland and returned with the booty from Zuromin to my family in Warsaw. On one of my trips I had an experience which was both tragic and comic. Upon reaching the Pomiczowek railway station all of the smugglers aboard would look out the window as if to get a whiff of the air on the border. It was then that I realized that the Polish smuggling rings were superbly organized.

Children were lined up for kilometers before the station waiting to welcome the train's passengers with a tip of their hats. All of a sudden I saw everyone grab their belongings and throw them out the window, and since everyone else did, I did likewise, Upon arrival we had to walk through the station's main building in order to hand in our tickets. At this point it became apparent that this was a trap and there was no way out.

We were all assembled and the men and women were divided into two groups. A police officer approached me since I was the first in my row and asked, “Are you a Jew?” I answered, “Yes,” and promptly received a slap in the face. The officer turned to the next in line and repeated the question and, since I had answered in the affirmative, he also replies “Yes.” The German was quite annoyed and hit the man several times. The third man in line also answered “Yes!” Apparently, he didn't understand the question. He received a barrage of punches and kicks. The women standing on the side sensed the mistake and began shouting “Nicht Jude,” meaning “Not Jewish.” As it turned out, I was the only Jew in the entire group. In the end, after extensive searches I was released and allowed to cross the border back to Warsaw. All the other males were arrested and sent to camps in Germany. It could be that my decision to tell the truth was wrong, but ultimately I saved my mother undue worry because she never would have known my whereabouts. While crossing the border I met two Polish women who were amazed by my release and refused to believe that I was indeed Jewish. “We know the truth,” they remarked, “but you have a Jewish head on your shoulders.”

My period of smuggling ended because there were no more goods left in Zuromin to bring back. Consequently, I decided to stay with my mother's relatives in Mlawa. I felt that this would enable me to help out as much as possible.

Every day our situation in the Warsaw Ghetto grew worse. Suffice it to say that the ghetto's inhabitants were forced to buy potato peels which they then cleaned and cooked in order to fill their empty stomachs. Many diseases (some previously unknown) became prevalent among the Jewish population, causing significant losses. This is not the place to elaborate on life in the Warsaw Ghetto. My consolation was the knowledge that I didn't forsake my family even at a time when I also was extremely impoverished. Every cent I earned I sent to my mother and two sisters (My stepfather had passed away in 1941).

The acts against the Jews in Warsaw continued. The ghetto was made even smaller and my mother and sisters were forced to move to another “residence.” The last news I received of my family was from my little sister, who was 14 at the time. She wrote that my mother and older sister Bilha had died of starvation in April, 1942. Unfortunately, I have no information about the death of my little sister Bruria. I mourn their deaths, I will never forgive Germany until my final day and I will strive to pass on my hatred for the modern-day Amalek nation to all future generations!

While in Mlawa during the summer of 1941, I was sent to forced labor together with a group of 100 youths. We paved the road linking Grodosk and Przasnysz. I tried to ease their suffering through my contact with the German commanding officer and by providing first aid. Prior to our departure, a man named Yeshayahu Kshesta (whose job was to send forced laborers to the Germans) approached me. He handed me a sum of money to be used in the event of an emergency since he had no idea what awaited us in the work camp.

When we arrived at our destination in the village of Czarnyż, I handed over a list with the names of the group's members to the man who was designated as our commandant. Since he had difficulty reading our names, I offered my assistance, and he then appointed me as his unofficial aide. He had me toil eighteen hours a day. In addition to my maintenance duties in the camp I worked in his office as a translator until late at night. After a short while a misunderstanding arose between us and he sent me to work in road construction. The work conditions were extremely difficult. We slept on a flimsy piece of straw spread out on the floor. The work on the road was back-breaking but fortunately there was still sufficient food at this time. In addition to our regular food ration I obtained a permit from the Germans which enabled me to buy salami in exchange for official payment at the local butcher.

On June 21, 1941 we spotted a squadron of the German Luftwaffe flying overhead on a mission to bomb Russia. This didn't change our routine in the slightest and we had to continue working until the snowstorms began. Afterwards we were sent back to the Mlawa ghetto. We continued working, mainly plowing snow on local roads.

Our troubles multiplied every day. In the spring of 1942 four Jews were hung because of monetary violations. A short while later the Germans laid siege to the ghetto and captured 100 Jewish hostages who were unable to prove that they were employed by the Germans. Afterwards, 17 men and two women from the local Jewish police and Judenrat were shot in front of the ghetto's entire Jewish population. Of the 100 Jews taken hostage, 50 were released in return for a ransom of gold, jewelry and furs. The 50 others were shot and buried in a communal grave.

The Holocaust was closing in on us day by day. We spent the summer in an abandoned army camp in Nosarzewo, which prior to the campaign against Russia had served as a German base. My job was to maintain the locks on the huts. After our release from Nosarzewo we were once again sent back to the Mlawa ghetto.

On November 8, 1942, 2000 of us were assembled inside a flour mill. The next day we were taken to the train station, headed for Auschwitz. Of course, we had no idea we were going to Auschwitz nor what awaited us.

Another image remains imprinted in my memory. As we passed Czestochowa, we saw a group of famished Jews working on the railroad tracks. At the risk of losing their lives, they signaled to us what was in store by placing their hands around their throats; nevertheless, we refused to acknowledge the significance of what we had seen. We continued to think that we were simply on our way to work camp. The truth was that our group was relatively lucky. Out of 2000 persons, 530 men and 360 women were selected for work camp. After a month and a half there was another selection in the women's camp and this time only 10 women remained alive. The men were more fortunate. One hundred thirty young men were chosen to go to construction school. This gave them an additional three months before the next selection. The initial period was the most critical. Adjustment to the camp conditions was especially difficult for those who arrived in Auschwitz who, prior to their arrival, were sheltered by their parents. All of a sudden, upon entering the camp, they had to fend for themselves. Many were broken in spirit. Some committed suicide by walking up to the electric fence, where they were either shot by guards or electrocuted by the electric current.

We received food rations which didn't provide adequate nourishment. Twice a week we received a double portion of “salami” and bread which helped a bit. We were under the impression that the double rations were supplied by the Red Cross but 10 days later, after receiving three such rations, the supplement was stopped. Those who had been in the camp longer than us tried to console us. They told us that apparently the Germans were hoarding bread in order to hand out larger portions for the Christmas holiday. Christmas passed, but we didn't receive any extra supplement. Many prisoners starved to death.

After one month everyone lost considerable weight, and we turned into “muzelmen”. A rumor broke out that the Germans were distributing whole loaves of bread to everyone. This is indeed what happened, but a great disaster, apparently planned in advance by the Germans, resulted. Most of the prisoners couldn't control their sense of hunger and ate the entire loaf of bread in one sitting, causing them to fall sick with dysentery. Their stomachs couldn't digest such a large portion of food and consequently they died. Since I had endured difficult times prior to the war, I was able to predict the changes that take place under impossible conditions when humans lose their humanity. I witnessed sights such as one person dominating over another and human beings behaving like animals by eating food discarded by someone else.

I recall the relatively easy period during 1944 when Hungarian Jews arrived in Auschwitz. I saw a Jew with what was once a round belly who looked like someone who in the past had been well-established. He was bending over a large wooden barrel – a container for soup which was dished out to the prisoners. He scraped the sides of the barrel with his spoon and fed himself spoon by spoon. This picture may not seem heartrending, but it is etched in my memory.

While standing in line during inspection (which sometimes lasted hours) I had time to contemplate our situation. I thought of those who believed that it would be to our advantage if we complied with the Germans and exploited our brethren. Conversely, I reasoned that since in any event there was no prospect of our escaping alive it would be pointless to torture fellow Jews. If we were destined to be saved, then we were surely better off remaining human.

For a while I served as head of a ten-person construction crew. Often I had to fill in as a substitute worker for someone who had “business” to take care of with one of the civilians who worked with us. I managed to extricate myself from this work and was accepted into a group which worked on agricultural experiments. They were attempting to grow a certain type of flower from which latex could be extracted. Another group worked on growing flowers and vegetables. It was occasionally possible to steal several tomatoes or cucumbers and exchange them for additional bread or soup in the camp. This made life a bit more bearable, and the experience taught me a certain principal of life – as long as one is suffering from starvation, he has no time to think about anything other than how to obtain an additional slice of bread or bowl of soup. We were in “good spirits.” We had no time to philosophize or ponder the future. On the other hand, during the times when we were able to acquire some food (at the risk of our lives), we would sit around and began talking about what awaited us in the future.

On June 6, 1944, while working on a beekeeping project with an S.S. expert on the subject, I noticed a newspaper held in the hands of the Nazi's friend. The headlines reported the opening of another front in Normandy, France. Whatever the situation was, the Germans weren't going to keep us alive, so our mood soured dramatically. And so the days, the weeks, and the months passed in Auschwitz: selections, deportations to other camps, endless hardships, rumors and prophesies. Although the news of the front instilled a certain hope in us regarding the future, the full-scale extermination of Hungarian Jewry continued – 20,000 people per day.

Many of the old-time inmates refused to remain silent and took an active role in the underground. Some passed on information updates from a foreign radio station, picked up by a hidden radio. Girls who worked in the manufacturing of ammunition succeeded in confiscating small quantities of gunpowder and transferring them to the zonderkommando groups (whose job it was to burn the bodies of the dead). In addition to several grenades in their possession, they built home-made bombs. Also significant was the acquisition of a 36-bullet revolver purchased from an S.S. man by Chaim Bursztejn of Mlawa. He paid $2,000, which had been transferred at the risk of death by the prisoners who sorted the objects of the dead.

The ammunition was then transferred by Wolek Newman and me to our workplace in preparation for the escape of three Jewish leaders. To our chagrin, the plan was never actualized. The ammunition was later transferred to Herszel Itzkovitz (Lempek), who today resides in London. He hid with Vollek and another man in camp territory after the inmates were sent on the death march to other camps. I would like to commemorate the blessed memory of Wolek Zev Newman, born in Zyrardow, who died a heroic death during the War of Independence.

After the extermination of the majority of Hungarian Jewry, the job of the zonderkommando became superfluous. Through various schemes, the Germans liquidated most of them, until only 200 remained. The Germans planned on killing another 100 of them at the end of October, and it was then that a rebellion broke out. One hundred young men lost their lives after throwing their German kapo into a furnace, cutting the camp's barbed wire fence and running armed with weapons into the fields. Meanwhile, the Germans discovered that gunpowder had been stolen, and four of the Jewish girls paid for this with their lives. May their memory be blessed.

On January 18, 1945, after 26 months in Auschwitz, I set out on a journey with the rest of the inmates. This journey took its toll in the death of many thousands of male and female inmates who had managed to survive until this point. After four days we arrived at the Wodzislaw railway station. We were packed into freight trains; groups of 100 people were packed into each railway car. Fate had it that our group was assigned to the smallest car, a ten tonner. Since it couldn't contain the whole group, five people from the right and five people from the left were ordered to board neighboring cars. There wasn't even enough room for the guards in our car. The severe crowding and the fact that there were no guards present enabled us to plan an escape.

I made an offer to my friend Yitzhak Perl and he agreed. Our train stood on a railway line which was laid above four intersecting tracks. The train couldn't depart because of a red light, and I took advantage of the delay and purchased a civilian coat from one of the inmates in exchange for half a loaf of bread. Perl had second thoughts and regretted his decision. Then, without hesitation, Mendel Friedman from Neistat volunteered to join me on my mission. I explained my simple plan to him: when the train started moving out, and before the train picked up its full speed, we each were to jump to opposite sides. We arranged to go to an isolated hut in the field, since it was highly unlikely that Nazi Germans dwelled there. The plan was to verify where we were located and decide on our next destination.

The operation began with each of us departing in a way which seemed to foretell his fate. Mendel said, “Guys, if you hear gunshots, you'll know we didn't make it.” I said, “Stay well, I'm going.” After jumping, we laid on both sides of the track. The train passed by at a slow speed. When the last car went by I noticed an S.S. man running after the train and then suddenly stopping next to us. We had been covered in sheets which camouflaged our bodies in the snow. I managed to quickly cover my head again with no idea what was happening with my friend. I heard the click of a revolver and a gunshot hit my friend. I heard him moan. After an instant I heard another click and yet another bullet hit his body. At this moment I blacked out, convinced that this was the end of my life. After an unknown period I regained consciousness and heard my friend's final moans of death. I sensed that the S.S. officer was standing over me, poised to kill me any second. This uncertainty almost drove me to madness. After much deliberation, I decided to slightly lift the sheet above my eyes and see what was ahead. I saw only my friend's body, uncovered and almost quiet and I didn't see the S.S. officer in front of me or anywhere in the vicinity.

I realized that there was no point in remaining at the site of the disaster, for I couldn't help my friend. I could only leave and do alone what we had planned to do together. I reached the hut and discovered that I was 18 kilometers away from the city of Nowy Bogomin. I instantly recalled that while in the concentration camp I had written short letters in German for a Pole named Czichetski, whose wife lived in this city. Having no alternative, I folded the sheet, put on woolen earmuffs in order to conceal the fact that hair was missing from my head, and then, on a clear moonlit night set, out on foot opposite German army troops on their way to the front. After three hours, I reached my destination.

I located the Czichetski family bakery which at the time was run by the wife, since her husband was in a concentration camp. He was charged with underground activities after being betrayed by one of the underground members – a doctor named Galuszka. I uncovered considerable information regarding their activities through my letter-writing and this proved invaluable in establishing a relationship with his wife.

When I arrived at the bakery I knocked on the window pane. The wife opened the counter and asked, “How many loaves of bread?” Because of the curfew I was in an extreme rush. I responded with a question: “Is your husband already home?” She replied with another question: “Are you from Auschwitz?” “Yes,” I answered, whereupon she opened the door for me. When I entered, she sat me down next to the table and offered me food and drink. I broke into tears. She asked me why, and I informed her that I hadn't sat at a table fit for humans in six years! I immediately told her about my relationship with her husband, making a point of mentioning the name of the informer. This was the most significant proof of the validity of my words. In the midst of the conversation, I discovered that unlike her husband, she was an anti-Semite. I therefore took special care not to reveal my identity. In order to avoid praying and crossing my heart during the meal, I told her that if God could do what He did to our Poland during the war, I didn't believe in God. This exempted me from all responsibility to pray or perform Christian rituals.

She prepared a bed for me. More than anything, my main fear was that I would inadvertently reveal my Jewish identity in my sleep. The wife, a “woman of valor,” knew how to establish ties with men in the Gestapo, and by bribing them was able to save her husband's life. One man from the Gestapo visited her regularly and informed her that many of the prisoners had succeeded in escaping, but that appropriate action had been taken and all of the escapees were caught. In my heart I laughed at her and at the man from the Gestapo who remained unaware of my true identity.

After six weeks of rest, one of the bakery workers discovered that I was being hidden by the baker's wife. I was forced to leave this hideout and find shelter among other families whose relatives were interned in Auschwitz. I received their names because I insisted that it was their obligation to help me, posing as a member of the White Eagle underground from Pomerania. I took advantage of the fact that I was familiar with the city of Grudziądz (the place where I had lived while studying at the technical school). Indeed once, while staying at the bakery, I was visited by a man from this city who apparently intended to verify my claimed identity.

I spent the next seven weeks living in sub-human conditions until being liberated by the Red Army. I slept in a haystack, was unable to shower or shave, and practically had no food. My host was one of the village farmers whose cousin had been killed in Auschwitz. I was able to stay there by convincing him that I was his cousin's close friend.

Whi1e lying idle inside a stack of hay, as if in a grave, I allowed myself to sing parts of holiday prayers which, as a boy, I had sung in the synagogue choir in my hometown. One evening during the month of April I noticed that the full moon was approaching. Knowing that Passover can't fall on Monday, Wednesday or Friday, I decided that the last day of Passover would fall on a Thursday, based on the position of the moon. I often counted eight days (since it is customary to celebrate eight days in the Diaspora). On the eighth day it is the custom to commemorate those who passed away. Although I was far removed from religion, I decided to commemorate my father, as I had since my childhood. I then commemorated my mother, who perished at the age of 52, and my sisters Bilha, aged 19, and Bruria, aged 14. I cried incessantly over my loss as well as the loss of most of Polish and European Jewry. I didn't believe that all of the prisoners transported to the heart of Germany were alive. There I was, a young Jewish man all alone, desperately surviving under difficult conditions.

Following the liberation of the city by the Russians, I returned to the bakery. I then had to deal with a very embarrassing situation. The city had been the site of a dispute between the Poles and the Czechs as to who was in control. The Czechs found a liberated prisoner and asked him to serve as mayor, since they felt his past prepared him for this job. When the Poles got word of this decision they took me to the municipality building and asked to appoint me as mayor. I somehow succeeded in extricating myself from all this, claiming that I wasn't a native.

On the first night after my liberation, I couldn't fall asleep because of excitement and uncertainty as to my future. The baker's wife, her sister and their maid, fearful of being raped by the Russians, ran away and spent the night in a fortified home. While alone in the apartment, I discovered a record player and thought that I might also find some records and in this way pass some time. I opened one of the cabinet doors and found several old records. I picked them up and was astonished and shocked at my find. I was holding Hebrew records in my hands! I put on a record of choral music called The Western Wall and heard a melancholy melody accompanied by crying and lamentation. I broke into tears, not certain in which world I was living. I came to the conclusion that the house originally belonged to a Jewish family. This factor motivated me to leave as soon as possible (before the women returned home).

For two days I traveled: first to Auschwitz, Warsaw and finally to Mlawa. At the Katowice railway station, I found out that there was no more room left on the train. I walked around the platform and jumped through an open window on the other side. A railroad policeman approached me, pointed his gun at me and ordered me to alight. I pulled up my shirt sleeve to show him the number tattooed on my arm and shouted, “Whom do you think you're sending away?” This worked like magic: both the policeman and the people all around looked at me as if I were holy. They took me into one of the compartments, vacated a seat, and showered me with food and drink.

I feel it is my obligation to mention the triangle tattooed on my arm underneath the numbers which symbolized my Jewish identity. It is because of the presence of this symbol that, while staying at the bakery, I took a piece of sandpaper and rubbed the spot until it bled so that the scab would cover the triangle. As a result my Jewish identity wasn't revealed on the train ride.

When I finally reached Warsaw I went to the northern railway junction, where the trains left for Mlawa. The station was completely demolished, with no sign of a railroad. There I met two Poles who were also headed for Mlawa and I told them that in that town I had four friends who had studied with me at the technical school. After hearing their names they exclaimed, “You're one of us!” They then gave me food and drink. They carried a small suitcase with them as they walked down the track, which was passed from hand to hand every now and then. I offered to help out, and upon lifting the case I remarked that it was small but heavy. I then discovered that the suitcase contained smuggled arms which were intended to be used against those Jews who had survived.

You can imagine what a trying situation this was for me. All along the train ride to Mlawa I was afraid that at the Mlawa railway station I would meet someone who would recognize me and betray my true identity. Therefore I tried to rid myself of my “friends”. In Mlawa I found a handful of survivors, among them Leah Bromberg from Mlawa and Bebba Epstein from Pruzhany, whom I knew from the concentration camp. After obtaining forged West German identity papers, six of us – the two girls and four young men – succeeded in escaping from Poland. After two weeks of trial and tribulation traveling through Germany, we finally made it to the English sector and from there to the city of Marburg on the Lahn River.

We remained in Marburg for three months. Thanks to Jewish soldiers serving in the American army we were able to correspond with our families in Israel, America, and Uruguay via the military postal service. I passed up the opportunity to immigrate to the United States even though my grandmother, four uncles, three aunts and their families lived there. The deep emotional bond which was established during the arduous journey tied my destiny to that of Bebba Epstein. We decided to build our home in Israel, where through the efforts of a Jewish officer passing through France on his way to the United States, the papers were sent to us in Germany by a Jewish soldier. Thanks to them we reached France, where we were received and cared for by emissaries from Israel. We arrived in Israel aboard the illegal immigrant ship Tel Chai in March, 1946.

To my amazement the white sheet, which saved my life when I jumped from the railway car, is still in my possession, though I have no idea how I managed to hold onto it throughout my long journey. No sheets were distributed in the concentration camp, but I had a friend who worked in the camp laundry and, perhaps most incredible, two letters were embroidered on the sheet – my initials.

I'm not a writer and I lack the talent to express all my emotions and all that I experienced during the years of the Holocaust. I wish, however, to leave a living testimony to future generations, so that they shall know the history of our people, always to remember and never to forget.

|

|

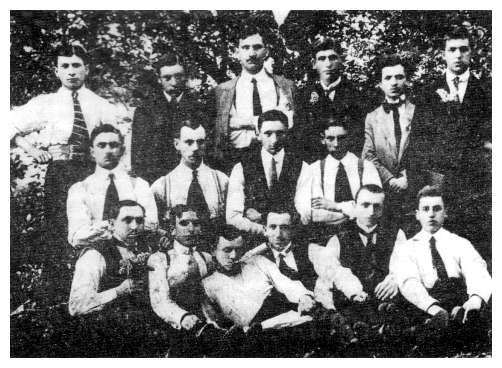

Members of the Bund organization in 1916. Top row: Avraham Lichtman, Shalom

Abramowicz, Eliahu Dragon, Ichka Frajd, Chaim Rozensztejn, Moshe Krulik,.

Middle row: Zisha Rozensztejn, Eliahu Frajd, Yosef Bruk, Yoska Frankel.

Bottom row: David Abramowicz, Meilech (Elimelech) Szklar, Digola,

Peretz Gutenberg, Gedalyahu Kubelsman, Ber Jablonka. |

|

|

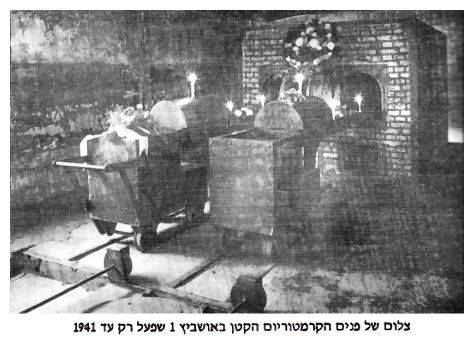

A photograph of the interior of the small crematorium

in Auschwitz that operated only until 1941. |

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zuromin, Poland

Zuromin, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Lance Ackerfeld & Osnat Ramaty

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 29 Feb 2008 by LA

Zuromin, Poland

Zuromin, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page