[Page 617]

Yedinitzers – Extraordinary People,

In the Land of Israel

Ezriel Adelman – A Man of The First Aliyah

by Asher Goldenberg

Translated from Hebrew by Laia Ben-Dov

| Our town Yedinitz took a role, whether small or large, in all the emigrations to Zion, from the First Aliyah until the establishment of the State of Israel and the Aliyah of the survivors of the Holocaust. Also, among the first people of the First Aliyah, we meet a young lad born in Yedinitz; his name is Ezriel Adelman. |

He was born in 1862 (5622) to a distinguished Zionist family. His father, Reb Alter, was educated and was one of the first intellectuals in Yedinitz and Bessarabia. To support his family, he held a wholesale whisky-blending house, known then as “Podwal.” The son was a vegetarian and a writer. He published an article in the “Hatsfira” which appeared in Warsaw regarding the laying of a cornerstone of the large synagogue – Di Shul – in the town in the year 5639 -1878. He made Aliyah to the Land of Israel at the age of 26 in 1888. Together with other people from Bessarabia, all with experience in agricultural work, he settled in the southern village of Kastina (today: near Be'er Tuvia and Kiryat Malachi), which was supported by Baron Rothschild through his officials. Disputes broke out between the settlers and the hard-hearted officials. The quarrels caused a collapse of the settlement in Kastina and the village scattered. Ezriel returned to Bessarabia, but his father, Reb Alter, made Aliyah to the Land of Israel with his four daughters, and he settled in the village of Rechovot. During the time of the Second Aliyah, two of his daughters immigrated to America, and the other two remained in the Land of Israel.

One of the daughters settled with her father in Rechovot. Her husband had an orchard and was one of the first experts in the country on drilling for water. To his bad luck, the husband was killed when he went down to investigate the depth of a well in Rechovot.

The second daughter married a bank clerk, one of the first builders of little Tel Aviv, before World War I. Their house is located on Nachlat Benyamin Street.

The two sisters who emigrated to America returned to the Land of Israel during the 1930s. At that time, Ezriel also returned. All of them settled together in Rechovot, near their father.

When Ezriel returned to Yedinitz in 1890 after staying two years in the Land of Israel, he continued to work in agriculture. He managed large-area farms and acquired the reputation of being an expert in cultivating field crops.

[Page 618]

On summer days he was attached to his horse, and he was frequently seen riding in the fields. On winter days, when the fields of Bessarabia wore a covering of white snow, he would travel to Warsaw and study under the writers of Israel accustomed to sitting over a cup of tea in the home of the writer Dinazon, a perpetually single man like him. He was the one who mediated between the Tushia publisher in Warsaw and Yehuda Steinberg for the publication of his first literary works.

He did visit almost every winter with his father and sisters the Land of Israel, who he had made Aliyah at the height of the First Aliyah or the beginning of the Second, and they lived in Rechovot. He purchased at an opportunity a holding of a vineyard and an orchard. In the end, he returned to the Land of Israel during the 1930s and settled in Rechovot next to his orchard.

When I arrived in the Land of Israel in 1933, I found that Ezriel Adelman had arrived that year from abroad and all the members of his family living in his little house at 55 Nachlat Benyamin Street. From then on, he did not leave the Land of Israel. He passed away at the end of the 1940s, old and in full of his days, at an age close to 90. In the last years of his life, he lived in a home for the elderly on Labor Street in Tel Aviv.

* * *

At this opportunity, I wish to mention another person also from the First Aliyah, the father-in-law of Avraham Milgrom, z”l, one of the senior leaders of the Zionist movement in Yedinitz, Leib Kormansky. Even though he was a resident of the nearby town in Briceni, we can regard him as one of ours thanks to his strong connections with Yedinitz. He was the owner of a holding in the village Volodan[1], next to Yedinitz. All the members of his family, his son-in-law, and his brothers settled in Yedinitz and managed a wide-branched agricultural businesses in its vicinity. The two towns together, Yedinitz and Briceni, could therefore be honored by the Aliyah of Kormansky. At the end of the previous century[2], he bought an orchard in Petach Tikva, but because of his illness, he was forced to liquidate it and return to Europe. He passed away on the road in Italy.

Among the Yedinitzers who participated in the Second Aliyah, I remember five: Yitzchak Rosenthal-Raziel; the second person who made Aliyah to the Land of Israel with the Second Aliyah was the late Yisrael Weinshenker (Gefen) with his father the Chasid, who was known as Nachman-Menashe, and his daughter Pesia. And the fifth one was Eliyahu Tapuchi.

Moshav Hadar-Am

Translator's footnotes:

- Today's Volodeni return

- Refers to the 1800s return

[Pages 619-620]

|

|

Dr. Kuka Pizelman (Yehudit Kozlov)

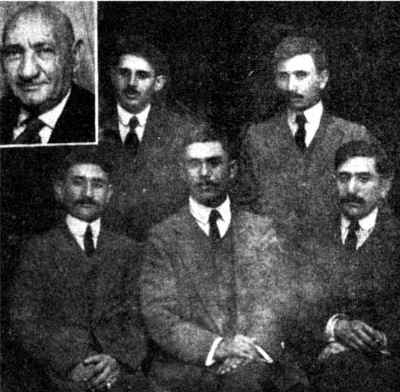

Among the heads of the “Tzierei-Zion” movement and its activities in Russia, immediately after the February Revolution broke out, a nationwide conference of the heads of the movement was held in Moscow in March 1917.

In the picture, from right to left, in the first row, sitting: Asher Shapira, A. Grobman, Yisrael Ritov

In the middle row, sitting: Moshe Pecker, Eliyahu Munchik-Margalit, Dr. Yehudit-Kuka Pizelman-Kozlov, Eliezer Kaplan (the first Minister of the Treasury of the State of Israel), Shmuel Shraier-Shapira

In the upper row, standing: Eliyahu Reiss, David Mirenberg, Yisrael Mariminsky-Mirom, Dr. Mordechai Helfman. All the others became prominent Zionist leaders and were active in social and political roles in Israel. |

[Pages 619-624 Hebrew] [Pages 623-626 Yiddish]

Dr. Yehudit Kozlova [Kuka Pizelman]

– The Olah on the “Russlan”

By Yosef Magen-Shitz

Translated from Hebrew by Laia Ben-Dov

| “Russlan,” the ship of the olim that brought the first olim from Russia to the Land of Israel after World War I and after the Balfour Declaration is sometimes compared to the ship “Mayflower” (1620), which brought the first British emigrants to North America. In this ship, the well-known daughter of our town made Aliyah to the Land of Israel from Russia. Her name at home was Kuka, of the Pizelman family, and in the Land of Israel, she was known by the new name of Dr. Yehudit Kozlova, the family name of her husband. Her father, Reb Zeida Pizelman, z”l, was an honest, intelligent, and simple Jew who had a tavern for supporting his household. |

The generation of gray hairs and strengths knows to tell “miracles and wonders” about the daughter of the taverner from Yedinitz. Her name went before her during the years before World War I. To us, the generation of old age and wisdom, and entirely those who are younger than us, only a weak rumor reached our ears about Kuka. We encountered her when the remnants of the generation of gray hairs and strengths began to tell us about the past days when they were doing the job of writing the book about Yedinitz.

Kuka, as they called Yehudit, the daughter of Zeida Pizelman, was a “successful”

daughter from her youth, and her head, they said, was “the head of a minister.”

[Page 621]

She had a mouth – on “screws” (oif shraifelach), the elderly told us. And she also was beautiful. She had full braids, clear, dreamy eyes – a point of attraction to all the few gymnasia students in the town because she also was a gymnasia student. The father was not wealthy, and he had to make a certain effort to send his daughters to learn far away. At a very young age, Kuka finished at the gymnasium. At the same time, she also learned Hebrew and Jewish studies with private teachers in the town, especially with Yankel Hirsh Leibes Kizhner, on the same bench with the boys. She went through all the departments of hell of the “Numerus Clausus” (of the Czar and succeeded in being accepted as an ordinary student in the faculty of medicine at the University of Kharkov, which absorbed most of the Jewish students from Bessarabia and Ukraine.

She brought from her home a notable load of national recognition and knowledge of Hebrew, so much, that she was fluent in this language, a rare occurrence among the youth of her age, and especially among the girls.

In Kharkov, alongside the medical studies which she did not neglect, she entered intensive activity among the Zionist youth organizations. She was one of the founders of the “Tzeirei Zion” clubs in Kharkov University and was one of the leaders of this movement in all of Russia.

Despite her young age (she was born in Yedinitz in the middle of the 1890s), she was chosen to represent the Zionist student clubs in Russia at the 11th Zionist Congress in Vienna on September 2, 1913. This was the last Congress before World War I. In Vienna, along with the Congress, a world convention was held for “Tarbut,” the organization spreading Hebrew education and language, and she also took part there. The young delegate spoke in fluent Hebrew about the situation of Hebrew culture in Russia and on the need for wide activity. Her fluent and inflammatory Hebrew speech was a sensation not only in the Congress and its circles but also in all the expanses of the Zionist movement in Russia. And certainly, the Jews of Yedinitz and its Zionists were proud of that.

From then on, she participated in all the Zionist conventions, in the conventions of the Zionist youth, and at the “Tzeirei Zion” that took place in Russia. At the same time, Kuka did not abandon her studies and received a degree as a Doctor of Medicine. She even was drafted into the Czar's army and served in it for a short time as a doctor at the end of World War I.

With the fall of the Czarist regime, she broadened her Zionist activities. She participated in the conventions of “Tzeirei Zion* in Kharkov, Kiev, and Moscow alongside men like Yosef Shprintsak, Eliezer Kaplan, and others. Photographs in various archives that survived from those days testify to that. When the first ship of olim, the historic Russlan, left the port of Odessa, Kuka was aboard.

Mr. Shmuel Karmonski, a resident of Tel Aviv, one of the veterans who left the town, knew Yehudit-Kuka and her family in Yedinitz and afterward in the Land of Israel very well. He tells that she went home to visit, as far as he remembers, already after the Romanian occupation in Bessarabia in 1918. Her father, Reb Zeida Pizelman, sold his house and traveled with his daughter to Odessa. He also made Aliyah together with his daughter on the ship Russlan. He passed away in the Jerusalem during the 1920s.

[Page 622]

|

|

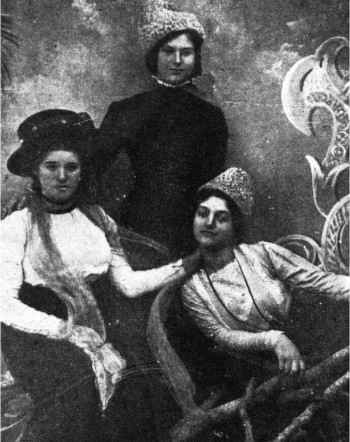

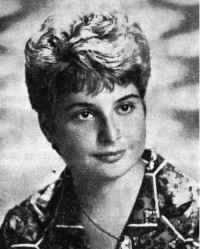

Three Educated Daughters – at the Beginning of the Century

From the right: Kuka Pizelman, a medical student, later Dr. Yehudit Kozlova, one of the heads of “Tzeirei Zion” in Russia, made Aliyah in the Russlan; passed away in Israel in 1965.

Standing: Tsipora, the daughter of Shmuel-Zelig Koifman, then a student in “Parabolic Courses” established by Alterman in Warsaw. After that, she was the first wife of the teacher Dubrow, the first kindergarten teacher in the town. She passed away in Yedinitz in 1923. The third woman in the photo is unidentified.

|

The departure of the ship Russlan from the port of Odessa is connected to an adventure unique of its kind. About a year before that, several tens of war refugees arrived in Odessa from the Land of Israel. At that time, the White Army of the Czarist General Denikin ruled in Odessa. The local Zionists requested and received permission to rent a ship “that will return the refugees of the Land of Israel to their homeland.” Permits to enter the Land of Israel were received from London. All of the olim were registered as “returning refugees” and before the authority, they had to appear as if they did not understand Russian.

[Page 623]

Among the olim , 671 in number, were writers, academics, learned people (Professor Yosef Klozner, Dr. Glickson, afterward the editor of Haaretz, Chaim Katznelson, the poet Rachel Blaustein, and others), teachers, engineers (the architect Zeev Rechter,z”l) who introduced the use of stilt columns (piloti) in housing in Israel, businessmen (Yisrael Guri, z”l, also a Bessarabian, and a relative of the Yedinitz family Woskoboinik, chairman of the finance committee of the Knesset; Rosa Cohen, the mother of General Yitzchak Rabin, the conquering general of the Six Day War), doctors, and among them Dr. Yehudit Pizelman (after her marriage – Kozlova), and others. The ship was on the way for 21 days, and it arrived in Yafo in Chanuka, 5680 (1919). The coming of the ship was surrounded by legends already when it was on its way, because Russia was cut off from the Land of Israel during all the years of the war, and the civil war that had then continued for two years, also did not ease the connections and awakened great excitement. Thousands came to welcome the ship. Then, they thought that dozens of ships would bring olim to the Land of Israel from Russia.

[Page 624]

Even though the hope for a large Aliyah from Russia disappeared, the legendary halo of the Russlan has not disappeared to this day.

In the Land of Israel, Yehudit, who settled in Jerusalem, devoted herself to the medical profession and she worked as an oculist for 15 years in the framework of the Hadassa medical organization in Jerusalem. She especially devoted herself to the removal of the trachoma disease. Yehudit was active in the then-illegal “Haganah,” especially in the medical service, and after the establishment of the State of Israel, she served as a doctor in the Israel Defense Forces. Her family life was not good, and she separated from her husband. Her son, during the first days of the establishment of the State, was appointed in charge of fuel. She also had a daughter. Yehudit Kozlov represented the State of Israel and the doctors of the Land of Israel many times at international conferences and conventions in the USA and Europe. She passed away in 1966.

[Pages 625-626]

Yitzchak Rosenthal-Raziel

– A Man of The Second Aliyah

Translated from Hebrew by Laia Ben-Dov

| Yitzchak, son of Abraham (known as 'Abraham Shloimele's, i.e. Abraham son of Shloimeleh ('Little Solomon')[1]. Rosenthal was born in Yedinitz, made Aliyah at the end of the Second Aliyah towards the end of 1911, and was a high school student at “Mikve Israel.” After that, he learned in the Hebrew Gymnasia in Jerusalem and finally in the “Herzliya” Gymnasia in little Tel Aviv. |

During World War I, he received Ottoman citizenship and was drafted into the Turkish army, where he passed a course to qualify him as an officer. He was active in the Jewish community in Haifa, in the “United Labor” of the 1920s, and various financial institutions of the Histadrut.

After World War I, he came to visit Yedinitz. Asher Goldenberg was incidentally at the same train station, in the village of Dondushan when Yitzchak arrived on a train in the late hours of the evening. He told me how happy the people from Yedinitz were to meet him. They got together and made him an impromptu party in the inn where travelers to Yedinitz would stay temporarily, and sometimes would even sleep there for a night.

When he returned to the Land of Israel he settled in Tel Aviv, and he even was chosen by the Histadrut as a member of the city council. But at the end of the 1930s, he moved to the “civilian” settlement circles and even represented them at institutions.

|

|

| Parting Picture from Yitzchak Rosenthal before His Aliyah in 1911

First, from the right: Yisrael Rosenthal, Yitzchak's brother, was one of the activists of T”zeirei Zion.” He visited the Land of Israel in 1939 and returned to prepare for his Aliyah, but he perished together with his wife and daughter in the Holocaust. The second one sitting is Pinchas Grubman, who perished in the Holocaust. The third, on the left, sitting, is Yitzchak Rosenthal (afterward, Raziel). In the frame above – Yitzchak in the last years of his life. The two others in the picture are unidentified. |

[Page 627]

In the riots of 5689 (1929), he was an active officer of the Haganah, in the Tel Aviv region.

Yitzchak married a pioneer from Grodno, a member of “the Labor battalion.” He gained a reputation in his profession, as one of the best accountants in the country.

He and his wife were people who welcomed guests, were generous of heart, and their house was a center for all who came from Yedinitz. They exploited their connections with a senior clerk in the Aliyah Department in Jerusalem, the late Eliezer Prodovsky, one notable of Jerusalem who also came from Grodno, to obtain the certificates for olim from Yedinitz. And indeed, they obtained the certificates, among others, for Baruch Blank and Asher Goldenberg with their families.

Yitzchak built himself a house and his family was respected in the Land of Israel, but unfortunately, his only son, Raziel, fell in the War of Independence. From then on, his wife, the lively, kind-hearted, and welcoming to all who came to her home suffered from severe melancholy, until she extinguished like a candle. In memory of his son, Yitzchak changed his family name to Raziel. Despite the tragedies that befell him, Yitzchak held his position and continued to be active in various public institutions until his last day (1969). He was 76 years old when he passed away. His daughter, Esther, lives in Tel Aviv.

Footnote:

- Yitzchak brought his parents to the Land of Israel. His father Avraham passed away in 1942, his mother Henia in 1951. His younger brother Shlomo, who was in the Land of Israel twice, passed away in Colombia in 1971. His two daughters are in Israel. return

[Pages 627-628]

Liova Gokovsky – The Parachutist Beyond the Nazi Lines

By Yosef Magen-Shitz

Translated from Hebrew by Laia Ben-Dov

| A son of our town, Liova (Aryeh) Gokovsky, z”l, belonged to one of the superior groups of the brave Jewish settlers in the Land of Israel during World War II. He was the first parachuter, an emissary of the settlements, and the Haganah organization behind Nazi enemy lines at the height of the international extermination and destruction of the Jews of Europe. Liova was not a hero for a moment, one who passed like a comet in the heavens of the history of the settlement and the nation. His deed sprang directly from his pioneering life and because of his dedication with all his might to matters of the nation, its national and social establishment, and to his rescue from the claws of the cruelest enemy in all our history. |

Liova was born in Yedinitz on the 14th of Nissan 5674 (April 10, 1914). His father, Zanvil Gokovsky, was a small fabric trader. His mother died in his childhood when he was 5 years old, so his grandfather and grandmother educated him. He studied in Hebrew schools and in the gymnasia.

Our group of friends, older by four or five years, established the renewed “Poalei Zion” and the Zionist working youth organization “Young Bar” in 1930. He joined the youth club. Two years later, he joined “Hachalutz” and spent a year at the pioneer preparation in Ripichan, which “belonged” to “Gordonia.” In 1933, when the first groups of preparation of “the Covenant of the Poalei Zion Pioneers” were established (I then acted in the movement's chapter in Czernowitz), Liova was taken out of the preparation course and appointed instructor (a wandering counselor preparing groups. He wandered from place to place; he protested, instructed, organized, reprimanded, strengthened, and encouraged the spirits. There was no organized budget for organized trips, and Liova traveled more than once in railroad freight cars, between piles of coal and stones, sacks of salt and lime, exposed to rain, and shivered from the chill and cold of the night. He was a kind of wonder-lad of the movement.

He made Aliyah to the Land of Israel in 1934 and joined Kibbutz Yagur. He was a member of the kibbutz until the day he died. When he was an emissary of the movement at the young kibbutz in Magdiel (later, Beit Oren), he met the wife of his youth, Ruth, of the Schwadron family, an olah from Vienna. They had three sons.

Liova was a trustee of the kibbutz and zealous of its way of life. I remember his statement, which he would occasionally repeat, expressing more than anything a firm position against the hesitations and doubts that attack a person in difficult situations: “Dos iz as ohn shoin” (Almost: That is that!)

[Page 629]

In 1938, he went together with Ruth to Romania as an emissary of the kibbutz to the “Dror” movement. Despite the difficult political conditions and the lack of restraint of the fascist Iron Guard, he did a lot in organizing the movement and establishing new preparation groups. When the War broke out between the Allies and Nazi Germany, Ruth returned to the Land of Israel. He returned later. When Romania, following the occupation of Bessarabia by the Soviets joined the forces of the Axis, Germany, and Italy, the roads were already in bad condition and he passed through Bulgaria, Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon, on every available means of transportation that came to him – airplane, ship, sailboat, train, and car. “Except for a donkey,” he added. When he returned, he was a successful counselor to the immigrating youth.

His profession at the kibbutz was a shepherd. It nicely absorbed him in this occupation. The nickname “the shepherd from Yagur” stuck to him also at the time he was in Romania, so that he called all the rescue parachuters “shepherds.” He would tell me (I arrived in the Land of Israel and at Yagur four years after him, in 1938) with enthusiasm about his flock and his sheep, how one should chase “until madness” after a sheep that goes astray, to return it to the flock, about grazing, and about the lambs that were fattened “without an evil eye,.” How did he arrive at being a shepherd? Liova told that when he returned once from the Nesher quarry near Haifa, he read on the bulletin board of the Yagur settlement that “we are looking for a volunteer” to work in the sheepfold. He immediately volunteered for this branch. “I said to myself,” Liova told me, “If the gentiles in Bessarabia can be shepherds and support themselves from the “bryndza,” why should I not also know this?” He had a gentle sense of humor. And a smile that revealed a good heart and did not leave his face.

In the riots of 1936, when he was drafted to help gather the “girls” from Magdiel, which served as the second place of concentration of the “Poalei Zion” olim from Romania after Kibbutz Yagur (on October 1, 1939, the kibbutz from Magdiel went to settle in the Carmel Forest. That is Beit-Oren.), he volunteered to work as a porter in the train station in Tel Aviv. Here also,was endeared by the members of the “collective squad” and held a central position.

In 1943, when news of the enemy was frequent from the exile, they suggested to Liova to parachute together with others into Romania, already occupied by the Germans, to bring inspiration to the sad nation and the youth. Liova agreed immediately. He wrote then in his notes: “We have to come to them, to the exile.”

The chapter of the rescue the parachuters began is full of glory and bravery, splendor and sadness.

There were a half-million Jews in settlements of the Land of Israel when World War II broke out. They took upon itself as a commandment to prepare for the hour in which the fate of the Land of Israel and the future of the entire nation would be determined. With the end of the war, efforts and means were invested in widening the framework of the Haganah organization. The permanent, conscripted unit, the Palmach, was then established. The settlements were expanded in the border areas, in the Galil and the Negev. The national and informative activity was spread out around the world. The settlement sent its volunteers to Jewish military units within the framework of the British army, the Jewish fighting unit, the Jewish Brigade.

[Page 630]

|

|

Aryeh-Leib Fichman

His son Micha, 28, born in, a

Member of Kibbutz Beit Oren, and

the coordinator of the Nachal Golan

farm, fell in the Syrian bombardment

on November 21, 1972 |

“The volunteers from the Land of Israel were the only Jews in the World War who fought, not from the obedience of the laws of foreign countries, but according to self-national awareness, as the sons of a nation standing with its own permission, and acting according to its free will…the Jewish units demonstrated we are a nation, and with the establishment of the Jewish Fighting Brigade (“the Brigade”) we arrived at an outstanding national appearance on the battlefront.”

(Moshe Sharett)

Through underground channels during those years, the financial help passed to the Jews of besieged Europe, but Eliyahu Golomb, the leader of the Haganah, dreamed of delivering hundreds of Haganah people into the heart of Jewish concentrations in Europe, especially in Poland, to organize the youth to fight for their lives and protect the honor of the nation. The negotiations with national and military circles of the Allies failed because of heartless clerks and officers who worried that the war against the Nazis would be seen as “a war for the sake of the Jews.” Later, Churchill allowed a small plan for the Haganah to penetrate a Jewish unit into Hungary for sabotage at the rear of the enemy, and for saving Jewish lives. But this plan failed, like its precedent. The parachutists' operation was approved only after that, in 1943. In the words of Moshe Sharett, z”l , in the foundation of this plan, a double purpose was placed: to help to the Allies by sabotage and for taking prisoners, and for the rescue of Jews. The Jewish Agency even took upon itself a large partial financing of the operation. “We wanted to split the thick darkness with many torches that light up at a distance. We could throw into it only a few matches, some of which were burned up completely before they burned out.”

(Moshe Sharett)

After he volunteered to parachute, Liova met, with the Haganah officer Eliyahu Golomb. He received the order to go out. Before that, he learned English, a language totally strange to him. He received preparation for parachuting; he practiced matters of sabotage, underground, and communication. He was transferred together with his friend Aryeh (Leibo) Fichman (a man of “Dror,” from Czernowitz, born in Hotin in 1920, member of Kibbutz Beit Oren) to Cairo, the headquarters of the Middle East Command of the Allies.to parachuting,was imprisoned, and released (after thathe had a tragic death in the Land of Israel.)

[Page 631]

On the night of Rosh Hashanah 5714 (September 29, 1943), Liova and Leibo left Cairo. Around their necks was the disk with the identifications: name, personal number, military rank. It was forbidden for a prisoner to give more information than that to his captors. It was forbidden for captors to request from prisoners to tell them more than that (in accordance with the Geneva Convention). Liova received the rank of a second lieutenant in the British Air Force and the pseudonym Yosef Kahana (Leibo – flight lieutenant had the name of Gidon Yaakovson). They took off that same night from the military airfield in Tukra, near Benghazi, Libya. Before they took off, they sent “last letters” to their wives, children, and acquaintances, an accepted condition by those going out to a dangerous operation. They were equipped with the Bible, money, and the awareness that “otherwise it is impossible.”

Liova and Leibo opened the chapter of parachuting behind enemy lines. They were the first pair of parachutists; another sixteen pairs followed in their footsteps.

On the night of September 29, 1943, a British airplane penetrated the airspace of Romania. To camouflage its operation, it distributed anti-fascist proclamations in various places. They were discovered and fired from the anti-aircraft protection rained upon it. During the shooting, a green light came on for parachuting. The two “lions” (Aryeh Liova and Aryeh Leibo) parachuted out.

But their luck did not play for them. The pilot made a mistake and parachuted them at tens of kilometers away from the target they had determined ahead of time (in Enet, near Timisoara). They parachuted them into the town Lipova. Liova fell on the roof of a house, and when he slid below it, he broke his leg. He was discovered, imprisoned, and hospitalized, initially in the prisoners' department in the military hospital in Bucharest, and after that in Brasov, Transylvania. Leibo was also caught; he stood under tortures in a cruel investigation, first in Romania and afterward in Germany. When he revealed nothing to his captors, he they returned him to Romania and imprisoned in the prisoners' camp in Timişu de Sus.

By the way, the members of the movement received prior notice that two “emissaries” were about to arrive. They did not know their nature. They knew about their arrival and that they fell into imprisonment thanks to an official communication the Romanian government published about the seizure of two enemy air force officers who parachuted “after their airplane was hit.” The names of the enemy men who parachuted revealed they were Jews.

Meanwhile, Liova succeeded in drafting two liaison officers as members of the movement (“Dror”), who knew that the parachutists had arrived.

One liaison officer, still in Bucharest, was a Romanian soldier who spoke Yiddish. He served as a regular accompanying guard (escort, in English) for Liova in the hospital. For a payment, and not only for a payment, but he also “volunteered” to give notes to members of the movement in Bucharest and to bring back notes from them. In the hospital in Brasov, Liova befriended the merciful nurse Iliana (she is Maria Tsika), who took care of him in the hospital. The nurse, with pure love and idealism, endangered her life and served as a faithful liaison officer between Liova and the outside world, and the movement.

[Page 632]

|

|

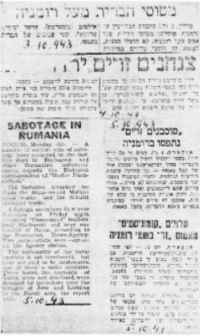

| The Land of Israel's newspapers notify of the seizure of “foreign parachutists in Romania” |

Liova's partner in parachuting, Leibo Fichman, also found a connection to the outside world in his prisoner camp through a Jewish dentist, Yechiel Shpringer, a resident of the city Brasov in Transylvania, who was drafted like all the young Jews to military forced labor. With the help of a Romanian friend, Shpringer established a military dental clinic that also served the prisoners from Allied armies. Shpringer was a faithful Zionist, who risked his life for the two prisoners from the Land of Israel. Through him, Leibo received the possibility of meeting with Liova, who was wounded and in the hospital. It is easy to describe the emotion of the first meeting between the two. The dental clinic also served later as a meeting place for them.

When the connection with the outside world was renewed, Liova received (from the rescue committee, the secretariat of the kibbutz, etc.) letters and even printed matter and newspapers from the Land of Israel. From within detention in the hospital, Liova was managing the movement, calling for the armed opposition in the danger's event of annihilation by the Germans and their Romanian helpers.

[Page 633]

Beyond a plan for uniting the movement (“Dror “in Regat and “Habonim” in Transylvania) and mainly encouraging the Aliyah in all conditions and circumstances, the movement realized somewhat a connection with the members who were expelled to Transnistria. A plan was crystallizing for smuggling people, expelled under the camouflage of transporting them to a military trial in Bucharest. A member of the “Dror” movement in Bucharest, Zvi Bassei, even visited and returned from Transnistria.

The pioneer movement was ready to organize the sailing of an immigrant ship to the Land of Israel, but the “adult” Zionists showed signs of hesitation and opposition to the sailing. The tragedies that occurred to the previous immigrant ships, mainly the Struma, were still in their memories. From the military hospital, where he was lying imprisoned and wounded, Liova instructed the men of his movement “to board the ship, whatever will be.” The members stood to obey the order, but the entire matter was canceled because of a wave of imprisonments that beset the Zionist adult and youth party workers, because of the treason of a double agent (the Swiss journalist Hans Walti), who served the Zionist underground and the Germans alike.

Meanwhile, it was sent from the Land of Israel to Romania additional parachutists. The next pair after Liova and Leibu, were Aryeh Lopasko and Yitzchak Makrasco, who parachuted on May 3, 1944, and were also caught in action. Those who came after them had better luck and were not caught: the pair Yeshayahu (Dan) Trachtemberg and Yitzchak (Meno) Ben-Efraim (on June 4, 1944) and the pair Dov Berger (Harari) and Baruch Kaminker-Kamin (on July 31, 1944). The last one, Uriel Kaminer, parachuted about ten days after the “liberation” (August 23, 1944).

These moved anew the entire Zionist movement and the youth organizations to action, to defense, and to operation. Weapons were obtained, “slicks” and bunkers were established, and the youth was training for self-defense. Emissaries went out to Budapest to organize the escape of refugees to Romania. They were encouraged to escape through counterfeit certificates from the camps of those who were drafted into forced labor. The blockade-running was renewed: five ships of Olim sailed from Constanza to the Land of Israel. An underground radio station was even established for communication with the Land of Israel.

During the summer months of 1944, there was a sharp turn in Romanian policy. Romania detached itself from Germany and became an ally of the Soviet Union. The Soviets were quickly advancing within the land. On August 23, 1944, Bucharest and Brasov were “freed.” The Germans were bombing the capital, and they released total chaos in the country. The authorities turned to the Allied prisoners asking for advice and insight. One of the Land of Israel's parachutists, Dov Berger-Harari, z”l, (he also was one of the sacrifices of Maagan) turned “in the name of the Romanians” to the Allied Air Forces headquarters in Poga (Italy), requesting to bomb the Romanian airfield next to Bucharest,at Aniasa which the Germans were still holding. The Americans answered the request and bombed the remains of the German holding.

The two freed parachutists, and the others who were not caught and met for the first time, immediately organized the youth and the Zionist movement towards coming events, also toward the unpreventable “red” future of Romania, of the Soviets, and the Communists.

[Page 634]

|

|

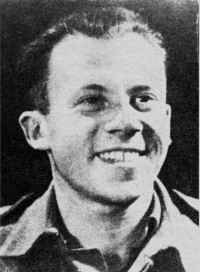

| Liova (in the middle) as a shepherd in Yagur |

And indeed, all the versions of the pioneer movement and the Zionist movement were broadened and strengthened, mainly the movement for the Aliyah. The matter was expressed by mass illegal immigration during the period before the establishment of the State of Israel at the end of the Mandatory regime, and in the mass immigration after the establishment of the State of Israel despite the incitement of those who encouraged the Soviet government and regime, regardless of the persecutions and suppressions in Communist Romania in its first days.

Liova and Leibu spent several more weeks in Romania after the liberation, and then they returned to the Land of Israel. In another place in this book, I mentioned I met with Liova when he was limping in Madg-al-Arab, somewhere in the western desert in Egypt in the camp of the Jewish Brigade where I served as a soldier. This was in October 1944, after he returned from Romania.

The purpose of the visit to the camp of the Brigade in the desert – no need was clarified to me; I think he came to meet those officers of the Haganah who had been soldiers in the Brigade, before, or after he was taken to the British intelligence headquarters to give a report, and apparently also to undergo a security search.

At that time, the Balkans were still under the Nazi boot, and so were Italy and France. We did not know to what part of the front we would be sent: to Italy, southern France, or the Balkans. I arranged a meeting with Liova for the next day, but I was told that he had left the place and returned to the Land of Israel. In our quick talk, he told me the circumstances of his parachuting and injury, and that he was to undergo treatment in the British military hospital.

Liova told all his deeds as a parachutist in enemy territory, his falling into imprisonment, establishing a connection with the outside world, the fulfillment of his missions while he was a wounded prisoner, and the story of his release, in a book of memoirs with illustrative and impressive contents, titled “What Happened to Me.” He signed it under the name of “Yehuda Achisar,” “Sara's brother,” his younger sister Sara, who perished together with his father in Transnistria. His brother in fate, parachuting, and death in anchorage, Leibu Aryeh Fichman, also published a book of memoirs entitled “Caught” and signed it to “A. Oreni,” in the name of his kibbutz, Beit Oren.

[Page 635]

And regarding Yechiel Shpringer, he made Aliyah to the Land of Israel together with his wife in December 1944. They entered the British camp of “illegal” immigrants at Atlit. The first ones to visit him in the camp were “Yosef” (Liova) and “Gideon” (Aryeh). And what happened to the merciful, noble nurse, Eliana Maria Tsika, who remained in Romania? The sources and those who know do not tell. I heard someone say that she wanted to come to the Land of Israel, but she could not do so.

In the Land of Israel, Liova was made a witness and active member in the war against the Mandatory regime, on our right to the Land of Israel, and the right of making Aliyah. He was a witness to the huge search the English conducted in his Kibbutz, Yagur, and to the revelation of the Haganah's weapons slick on the “black Sabbath” in June 1946. He showed opposition to the searchers for weapons, was arrested, and sent to prison in Rafiach together with thousands of members of the Haganah, arrested all over the country. In the camp in Rafiach, Liova filled the important role of communicator on behalf of the Haganah in the wing of the arrested kibbutz members.

After they freed him from Rafiach, Liova carried out all kinds of national and movement missions, among others in 1947. He went out as an emissary to the camp of arrested Olim in Cyprus. There, he organized the military training of the illegal immigrants imprisoned in the camps and the escape of many through the underground, and their transfer in ways-not-ways to the Land of Israel.

In the years following the establishment of the State of Israel, he was very active in his party, “the movement for the unity of Labor” (previously Party 2 within Mapai), which later united with “Hashomer Hatzair” in “Mapam.” Liova played an important role in the decision that “United Labor” would leave “Mapam” when signs of “liquidation” revealed by the leftists when the “cold war” grew stronger at the time of the Prague trials and the blood-libel against Jewish doctors in Moscow (“the murderers in white coats”). For a time, he served as the general secretary of a chapter of “Mapam,” and after that, of the renewed “United Labor Poalei Zion” (after the division in “Mapam”) in Tel Aviv.

Liova was then a visitor at our house. And now, as expressed in journalistic circles, “it is now allowed to reveal” that many of the “scoops” that I published in those years about the agitation in “Mapam” before the division, in the newspaper “HaDor” where I served as a writer on matters of internal policy and parties, originated in the long conversations and many arguments that I led with Liova, who then lived on the same street where our house stood.

Another activity in which Liova immersed himself in those days together with Dov Berger-Harari was the plan to memorialize the parachuting and putting out an album. He also kept a constant connection with the bereaved families of the parachutists who did not return home.

And here we have arrived at that tragic chapter, terrible and illogical, of the deadly tragedy, the shock in the anchorage.

On the 27th of Tamuz 5714 (July 29, 1954) in the yard of Kibbutz Maagan in the Jordan Valley, an assembly was held in memory of Peretz Goldstein, z”l, a man of the place, a parachutist who perished in Hungary on a rescue mission. The assembly was also intended to be a big memorial of the bravery and sacrifice of all the parachutists from the settlements in World War II.

[Page 636]

Thousands took part in the assembly, among them ministers, and at their head, the then Prime Minister Moshe Sharett, z”l, officers of the IDF, and public figures, and of course, the parachutists who operated in the diaspora. The assembly was supposed to raise anew the consciousness of the public and the youth toward that glorious chapter, that those small of spiritual stature tried to blur and erase. The organizers of this large assembly tried to give it an impressive appearance. A Piper airplane stood by to drop near the speakers' stage a small parachute bearing a letter of blessing to the assembly from the President, Yitzchak Ben Zvi, z”l. And then the terrible tragedy occurred. The plane flew so low that its propellers almost touched (and some say they did touch) the heads of those crowded in the first rows next to the stage. Besides that, the ropes of the little parachute were caught in the wheels of the Piper. The pilot lost control of the steering and a minute after that the plane crashed among the rows of guests. The destruction was horrible.

Fifteen people were killed on the spot and two more died of their injuries: among them four parachutists who had been saved from the valley of death: Shalom Pintsi from Kibbutz Gat; Lieutenant Colonel Dov Harari and Aryeh (Leibu) Fichman, both from Beit Oren, and Liova Gokovsky, a member of Yagur and a native of Yedinitz, one of its best sons. Among the others who were killed: Daniel and Ofra Sirani from Givat Brenner (Daniel was the only son of Dr. Chaim Ancho-Sirani, who parachuted into northern Italy, was caught ,and murdered by the Germans); Alik Shomroni from Afikim, one of the founders of the Nachal; Ben-Zion Yisraeli, a veteran of the settlers in the Jordan Valley, a member of Kibbutz Kinneret, a volunteer in the Jewish Brigade; an officer of the Military Guard, lieutenant Levi, and others; each one a tragic epic in himself.

Kibbutz Maagen was established by former members of the “Habonim” movement, the Transylvanian and Hungarian Chapter of the movement, and Peretz Goldstein,z”l,, aged 21, who parachuted into Yugoslavia on April 13, 1944, who was caught in Hungary and murdered in Germany,.

It was determined in advance that Liova would place a wreath of flowers in the name of all the parachutists at the foot of the monument in memory of Peretz Goldstein. Dov Berger-Harari, his parachuting partner in Romania, wrote to Liova the day before the assembly in Maagan, among other things, the following (July 16, 1954):

“I suggest that you place the wreath.

My reasons – the first who parachuted into enemy territory;

- disabled since the parachuting;

- member of our committee.”

They never got to place the wreath at the foot of the monument. Liova and Dov and Leibu didn't know that they would fall together as a sacrifice to that absurd, terrible tragedy that occurred ten years after they were saved from the claws of a bloodthirsty enemy.

The nation of Israel and the State of Israel are proud of the eternal splendor that they brought, and we, who came from Yedinitz, are seventy times prouder that there grew among us, one of the outstanding heroes of our nation, learned in troubles, suffering, and bravery.

[Page 637]

From the thirty-four parachutists who arrived at their destinations, seven did not return to us to the Land of Israel: Ancho Sirani; Chana Senesh; Chaviva Raik; Peretz Goldstein; Zvi Ben-Yaakov; Abba Berdichev and Refael Reiss. Of them, only three were brought to a Jewish burial in independent Israel: some of them arrived at Dachau, at the prison yard of Budapest, and hidden gallows in the deserted corners of Slovakia and Germany.

[Page 638]

Four of their friends who were saved were added to them, who perished in the tragedy at Maagan. Among them was the first of the parachutists on enemy land at the height of the war and the Holocaust to bring news of encouragement from the Land of Israel, of their vision to sorrowful, pursued, and destroyed brothers, Liova Gokovsky,z”l..

[Pages 637-638]

A Tear for A Friend Who Is Gone

by Aryeh Bard

Translated from Hebrew by Laia Ben-Dov

| It seems to me that when I came to Yedinitz, Liova had finished his pioneer preparation and worked in the Loan and Savings Bank to earn his living and also to save for the costs of Aliyah to the Land of Israel, and perhaps, also to help his parents in their need. With such youthful enthusiasm, he dedicated all his free time in the evenings to organizing the “Young-bar” chapter, joined mostly by youth from the narrow alleys and poorest levels of the town. |

Liova, in his great wisdom, knew how to influence parents to send their children to our chapter to attach to their enthusiasm for Zionism and building the Land of Israel. With such youthful excitement, he burst into organizing pioneer chapters of “Poalei Zion” that until then did not exist at all, and his success was so great, that during a short time he raised the “Hachalutz” chapters of the movement from an organizational standpoint, over the veteran “Gordonia chapters,” which had been organized for some time. All this he did with no help from an emissary from the Land of Israel (these appeared afterward). How hard he worked, and how much energy he dedicated to the organizational-professional activity among those boys and girls between 16-17, who served as marginals in shops and for craftsmen, tailors, and shoemakers, themselves existing with difficulty, and against whom it was necessary to fight a “war of positions,” so to speak, to find an hour from the 12 hours of their work, when they could turn to social activity.

I preserve a shocking event in my memory. That day in May 1932, my friend Shimshon Bronstein was arrested by the notorious Romanian Sigurantsa and tortured until he was disabled. This event wakened echoes in the entire Jewish world and in the non-Jewish ones. Also, it reached the British Parliament. Many remember the question in Parliament regarding this incident and how much courage there was then in Liova's pleasant conduct, full of Jewish understanding. He, the youngest in the society, knew how to strengthen weak knees and adopt strength to hide what requires hiding, and together with that, not to abandon any possible or impossible action.

When he made Aliyah, and I received the first letter from him, it was not a letter from a “pioneer” who was complaining about the pangs of absorption and first adaptations. This was a letter in which every word was filled with burning love for the Land of Israel and his kibbutz, Yagur, with a love without boundaries. The letter passed from hand to hand; it ignited hearts and lit desires to follow in his way. The “Halutz,” with emphasis on “the.”

Another event: This was in 1940 or 1941. When the first signs appeared of illegal immigration from Romania during World War II were received in Beit Oren, Liova gathered people from Romania at Yagur to bring them to Beit Oren for a reception. At the time of the journey, his boisterous happiness was limitless. If there is happiness in life, it was expressed in his smile, in his shining face, and bright eyes at the hour of his welcoming speech in the dining room of Beit Oren.

Among the sons of his city, his appearance at the first gathering of the “Yedinitzers” that took place in Tel Aviv, he was lifted on waves of love and appreciation, full of experiences, remembering things forgotten, and like a child who has many toys and doesn't know what to play with first; here he was, surrounded by hundreds of friends and acquaintances and didn't know to who to go to first.

Then, I understood what makes a man happy, one who was given such a love of friends.

Kibbutz Yagur

[Page 639]

Liova Gukovsky - The Parachutist Behind Nazi Lines

By Yosef Magen-Shitz

Translated from Yiddish by Ala Gamulka

| Our townsman Liova (Aryeh) Gukovsky belonged to one of the most heroic units of the Jewish community in Eretz Israel during WWII. He was the first emissary from Eretz Israel to parachute behind Nazi lines during the worst times. He aimed to save European Jews. Liova was not a hero of the moment only. His heroism was a logical result of his pioneering upbringing and his boundless devotion to his people and his country. |

Liova was born in Yedinitz in 1914. His father was Zanvil Gukovsky, z”l, a small businessman, a manufacturer. His mother had died when he was five years old, and his grandparents brought him up. He attended Hebrew school as well as high school. In 1928 he joined “Poalei Zion” and went to the preparatory kibbutz. He became an instructor of new members in the Pioneers of “Poalei Zion.”

In 1934, Liova made Aliyah and joined the Kibbutz Yagur, near Haifa. He remained its loyal member until his death. He was married to Ruth Shvedron (also a newcomer) and had three sons.

In the years 1938-1940, he was a kibbutz emissary in Romania. Ruth was with him. Despite much danger and transportation difficulties, he returned home after the outbreak of the war.

He was a member of “Haganah” and he performed many tasks.

In 1943, when news of the terrible happenings in Europe arrived, Liova undertook to parachute behind enemy lines.

[Page 640]

He wanted to motivate the suffering Jews and help them to resist. He wrote: “We have to go to them, in exile.”

This is how the heroic chapter of the Jewish parachutists from Eretz Israel who went into enemy territory, began. The Jewish community in Eretz Israel numbered at the time about half a million people. They were prepared for the decisive moment. The illegal “Haganah” was strengthened, as well as its military branch, the “Palmach.”

Settlements were extended, especially in border areas. The political and Zionist activities were bolstered. Around 30 000 young men and women volunteered to join the Jewish Brigade of the British Army and they fought in battles against the Germans. As a result, there was contact with European Jewry, and some material was even sent.

However, Eliyahu Golomb, z”l, the “Haganah” leader, dreamed of hundreds of its members reaching the places in Europe with a mass concentration of Jews to organize their resistance. Negotiations were underway with the appropriate political and military authorities of the Allies. However, these negotiations were sabotaged by officials and military personnel who were afraid that the Allies' side would have too much of a “Jewish character.” Finally, Winston Churchill, the wartime prime minister, intervened. The “Haganah” was permitted to send a unit to Hungary. Nevertheless, English officials allowed the plan to fail. It was much later, in 1942, that the British government confirmed the Parachutists Act to enter deep inside the land of the despised enemy. The purpose was to liberate Allied prisoners, especially downed pilots, and to contact the Jewish community.

Liova was one of the first volunteers for this mission. He underwent a special course for parachutists, conspiracy, radio, and signaling. He also intensively studied English.

[Page 641-642]

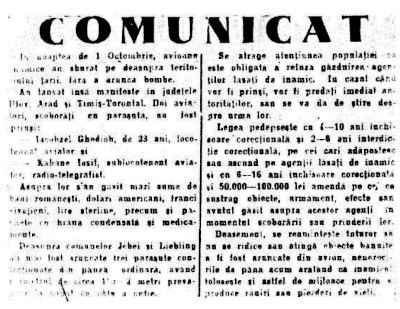

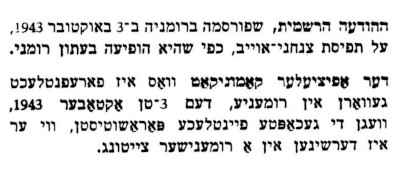

Official announcement published in Romania on October 3, 1943,

about the capture of enemy parachutists as it appeared in a Romanian newspaper.

On the night of October 1, enemy planes flew over our country without any bombing. However, they spread leaflets in the provinces of Lipov, Arad, and Timis-Torontal. Two pilots who parachuted were caught:

Gideon Yaakovson, age 23, a colonel.

Yosef Kahana, a pilot and wireless operator, a lieutenant colonel.

They carried large sums of money: Romanian currency, American dollars, Swiss Francs, Sterling pounds, and packages of food and medications.

Three parachutes were dropped over the towns of Jebel and Liebling (in Romania). They were made of ordinary materials and were 1.5-2 meters in diameter. At the end of every parachute there was a box. We bring to the attention of the public the fact that it is forbidden to give shelter to agents who were freed by the enemy. If they are caught, they must be denounced to the authorities.

According to the law, imprisonment of 4-10 years and 2-6 years of probation would be imposed on anyone who gives shelter or hides parachuting enemy agents. Anyone who takes items, arms, clothes, or money from the agents as they land or are caught, will be sentenced to 6-16 years in prison and a fine of 50-100 000 Lei.

Everyone is also reminded that it is forbidden to pick up any suspicious item thrown from an airplane. Many unfortunate incidents have happened until now and they are an indication that the enemy uses such things to cause injuries and a loss of life. |

[Page 641]

After spending time in Cairo in the command post of the Allied, he flew out on a military plane from an airport near Benghazi, in Libya to Romania. This took place on the eve of Rosh Hashanah (29.9.1943). Together with him on the same airplane came his friend Liova (Aryeh) Fichman[a], from Kibbutz Beit Oren. He was a well-known “Dror” leader in Czernowitz.

As camouflage, the British fighter planes had thrown flyers. However, the enemy discovered the plane and shot at it. The pilot then made a mistake. The green light for jumping was turned on several kilometers from the pre-determined location (8 kilometers south of Timisoara). In addition, they landed in the middle of the town Lipov, in Transylvania. Liova landed on a roof.

[Page 642]

He slid down and fell on a wagon. He broke a leg. Patrols came by and caught both parachutists. Liova was interned in a hospital for prisoners. First, he was in Bucharest and later in Brasov. Liova was tortured in Romania and later in Germany. He was then returned to Romania. The investigators were unable to extract any useful information from the two Jews from Palestine.

The day after the unsuccessful parachuting, an official communique was issued in Bucharest. It announced that “enemy planes that dropped leaflets were shot down. Two pilots parachuted. Their names were: Lieutenant-colonel Yosef Kahana (Liova) and Lieutenant-colonel Gadayev Yaakovson (Leibo).”

The leaders of “Dror” had been informed that emissaries would be coming.

[Page 643]

They did not, however, know who, what, when, where, and how they were coming. The official communique made it clearer.

Liova had two secret connections. The first was a Romanian soldier. It was his permanent “escort,” who also spoke Yiddish. He brought notes back and forth from the movement. Another note bringer was the nurse Iliana (Maria Tsika). She did it out of friendship with Liova and because of idealism.

Liova was interned in the prisoner camp of Timisul-de-Sus. There, he made the acquaintance of the camp dentist, a Jew called Yechiel Shpringer. He had been drafted by force into the army. Shpringer turned out to be an enthusiastic Zionist. He organized the first meetings between Liova and Leibo.

Liova wished to contact Constantinople, where there was a delegation from “Hagana” and the “rescue committee” of Jews in the Diaspora. He received letters and even newspapers, and other printed material from Eretz Israel. From the prisoner hospital, where Liova was located, he encouraged the Aliyah and armed resistance in the hope that if the Germans were defeated the Romanian Jews would be rescued - as it would be in other countries. He prepared a plan to unite the two sections of the movement – “Dror” in Romanian Regat and “Habonim” in Transylvania. There would even be a union with Transnistria. A member of “Dror,” Zvi Bassey, came to visit and returned peacefully to Transnistria.

In the meantime, more parachutists from Eretz Israel landed in Romania. They were not caught. They were Dov Berger-Harari, Yeshaya Trachtenberg (Dan), Baruch Kamin-Kaminker, Yitzhak (Mano) Ben-Efraim, and others. There was a further attempt at organizing a boat of immigrants to Eretz Israel. However, the older Zionists had doubts because of the sinking of the Struma and other boats carrying illegal immigrants to Eretz Israel.

From the hospital, Liova called on the members of the movement: “Do not be hesitant to board the boat.” The entire matter fell through due to the arrests of many Zionist leaders and youths. They were denounced by an emissary (a Christian). He turned out to be a double agent.

In the summer of 1944, there was news: Romania decided to break relations with Germany and to join the Russians. On August 23, the Red Army marched into Bucharest. The allied prisoners were freed.

[Page 644]

|

|

First meeting of the rescuing parachutists as Liova was liberated

Standing: Liova, Baruch Kamin, Yitzhak Ben-Efraim (Mano), “Marga”

Seated: Shaike Dan, Dov Harari |

Among them were Liova and Leibo. The other parachutists were liberated with the Zionist leaders who were preparing for what would come next - for Aliyah, and the occupation by the Communists of Romania.

The movement rises like yeast. It comes to fruition in the mass illegal immigration in the last years of the mandate and at the founding of the State of Israel.

A few weeks after being freed, Liova and Leibo left Romania.

In another section of this book, I described how I met Liova. It was somewhere in the western desert of Egypt, a few days after his return from Romania. I was then serving as a soldier in the Jewish Brigade. We were stationed in the desert before our departure for Italy. (At the time, France, three-quarters of Italy, and the Balkans were still in German hands.)

Liova came to us, probably to connect with his friends from “Hagana,” who were among the mobilized members of the Brigade. We arranged for a second meeting on the next day. However, he had to present himself at the general headquarters in Cairo to give a report and undergo a security check.

The entire story starts with his unsuccessful parachuting, falling into captivity,

[Page 645]

setting up the illegal connection, not fulfilling his mission having been captured, Liova wrote about in a book of wonderful and sad memoirs entitled “I Was Called to This Mission.” He signed it Yehuda Achisar (i.e., brother of Sara - his sister who, together with their father, was murdered in Transnistria). Leibo Fichman also wrote a book of memoirs titled “In the Hand.” It was written under the name of A. Oreni (referring to their Kibbutz Beit Oren).

Yechiel Springer made Aliyah to Eretz Israel. No one knows what happened to nurse Iliana in Romania.

In Eretz Israel, Liova was active in the movement for our rights to make Aliyah and independence. During the big search and discovery of hidden “Haganah” arms in Kibbutz Yagur, Liova showed his loyalty. He, together with thousands of members of “Hagana “was imprisoned in Camp Rafiach. (Black Sabbath, June 1946)

After his release from the camp, Liova fulfilled many missions. In 1947, he was among the unfortunate illegal immigrants in Cyprus. He taught young people how to commit to arms. He organized a large group to escape to Eretz Israel.

Later, after the establishment of the State of Israel, he became active in politics. For some time, he was in the Tel Aviv chapter of “Ma'pam.” During the discussions with the “Left Liquidators” of the party, he joined the split group of “Achdut Haa'avoda Poalei Zion” (left). He was then residing on our street, and I visited him often. We would hold many discussions. Based on these talks, I would write exclusive reports on the leadership of “Ma'pam” in the newspaper “Hadar.” I was a member of the editorial board and a correspondent for internal affairs and party issues.

Now we come to the tragic and awful event of the horrible killing in Kibbutz Ma'agan. Both Liova and Leibo lost their lives there.

On 29.7.1954, there was a mass assembly on Kibbutz Ma'agan in memory of the parachutist Peretz Goldstein, a member of the kibbutz. He had died in Hungary. It was a large group, with the participation of the then prime minister Moshe Sharett, ministers, members of the Knesset, top officers, and people from the nearby settlements.

[Page 646]

There were also parachutists, still alive, who had performed various tasks during WWII.

The purpose of the assembly was to revive the heroic chapter which circles had tried to minimize.

“A Piper airplane was to deliver a parachute bearing a message from President Yitzhak Ben Zvi to prime minister Moshe Sharett. This is when the horrible accident occurred. The Piper flew too low and the parachute bearing the message became entangled in the tires of the plane. The pilot lost equilibrium and the Piper fell and shattered in the crowd. Fifty people were killed on the spot and two more died later from their wounds.

Among the victims were four former parachutists: Shalom Pintchy (from Kibbutz Gat), Dov Harari, and Leibo Fichman (both from Kibbutz Beit Oren), and our Yedinitzer Liova Gukovsky, from Kibbutz Yagur.

Some of the other victims were: Daniel (an only son of the former parachutist Dr. Haim Enzo Sereny from Givat Brenner) and his wife Ofra; Elik Shomroni from Afikim, the founder of Nachal; Ben Zion Israeli, a founder of Kibbutz Kinneret, and a veteran of the Jewish Brigade and others.

Liova, as the first parachutist, was supposed to lay a floral wreath at the monument. It was to be unveiled. Sadly, it did not happen…

There were 34 parachutists who operated behind Nazi lines. Seven did not return. These are the famous heroes in the history of our liberation struggle: Enzo Sereny, Hannah Senesh, Haviva Reik, Peretz Goldstein, Zvi Ben-Yaakov, Abba Berditchev, and Rafael Reiss. Their remains were later brought for reburial in the State of Israel.

Fate would dictate that in addition to these seven, four more survivors of the war would be added. Among them was the first parachutist in enemy territory, who during the war and the mass murders of the Jewish people had dedicated himself to bringing a message of encouragement to his beleaguered brethren - Liova Gukovsky, z”l.

The Jewish people are proud of their sons and daughters and especially proud are, we, those from Yedinitz, that from our midst rose one of the biggest heroes of our nation at the time of the worst episodes of our history.

Original footnote:

- His son, Micah, 28 years old, from Kibbutz Beit Oren, later from Nachal-Golan, fell during a Syrian bombardment on 21.11.1972. return

[Page 647]

In Memory of Mordechai (Motya) Reicher

The Friend, The Cultural Activist, The Writer

From speeches given at a memorial assembly in Beit Neta,

in Petch Tikvah,

on 7.2.1971, thirty days after his death[a]

by Yosef Magen-Shitz

Translated from Hebrew by Ala Gamulka

|

It was difficult to accept the loss a month ago. It is doubly difficult to recognize the fact that today we erected a gravestone in memory of Mordechai Reicher. To you, the people of Petach Tikvah, Mordechai, Motya, as we always called him, a cultural activist, a researcher into the history of the “mother of settlements,” a discoverer of dust-covered stories. For us, people of his hometown, friends from the youth who studied together, who danced together in Zionist pioneering movements, who dreamed together of making Aliyah and redemption - he was also a friend, beloved by all of us. |

Motya belongs to a generation that grew into adulthood between the two world wars. It was a generation that established pioneering Zionism in Jewish towns that developed in Bessarabia. This was a province that was fed fully by its parent, the Jewry of greater Russia. Bessarabia played the role of a nationalistic-Jewish catalyst-pioneering Zionist group in a new Jewish format that arose immediately after WWI. This was the Jewry of greater Romania which, in turn, consisted of four different ethnic, cultural, and spiritual sections. This was due to an alternative past.

The Jews of Bessarabia sent Zionist activists, cultural emissaries, and teachers of Hebrew and Jewish studies to all parts of the “new and greater” Romania. The areas were parts of the former Austrian Empire, Bukovina - where Yiddish was spoken with a Germanic bent (or was it German with a Yiddish slant?); to Transylvania, where only Hungarian was used. Although there were many Jews there who wore Shtreimlach and Kapotas, they were abandoning the Yiddish language. We, from Bessarabia, strengthened its nationalism and introduced Zionist awareness, and the desire to do pioneering work. And finally, to the old Romanian Jewry, the tiny, pre-war Regat.

[Page 648]

|

|

| Mordechai Reicher giving a gift of books from Beit Neta (he was its director) to Prime Minister Golda Meir, on the occasion of her participation in the opening of the exhibition in honor of the anniversary of the third Aliyah |

This was a Jewry where some people spoke excellent Yiddish but in the archaic mode of “Zeina ureina.” They had difficulty with smaller letters. We, from Bessarabia, used to make fun of these Jews.

[Page 649]

We used to tell jokes about a Jew that was happy to see the letter aleph in a newspaper in Kishinev that was called “The Jew.” Another joke was about a Jew who was happy he had bought during holidays in the synagogue “A piece of Torah without blessings.” He did not know how to pronounce the blessings.

There were youth counselors from Bessarabia who went throughout the greater Jewish Romania, and Motya was one of them. He was one of the counselors from his youth movement “Gordonia,” in many places. I last met him in Czernowitz before I made Aliyah in the late 1930s. I was then active in a different section of the working Eretz Israel movement - “Poalei Zion,” on the right. This is what was called to differentiate it from “Poalei Zion” left.

He came from a family of hard workers who struggled to earn enough money to give their children a Jewish, general, and Hebrew education. I must admit that I, who was a knowledgeable member of “Poalei Zion” and who always tried to use proper terminology relating to the struggles of the classes, was envious of Motya. He belonged to “Gordonia,” which stood, so to speak, to the right of my movement. He came from a true proletariat background as his father was a tailor. He worked hard from dawn to late at night. I researched my own background and I found out that although my parents were cloth merchants the previous generation were tailors. I was very proud!

These discussions seem like youthful sins, silly matters. However, as I look back, I want to repeat a saying that is trite, but true. We laugh at it today, but it still evokes nostalgia: it struck us.

Motya first studied in a Cheder and later we attended together the private Hebrew high school that had been founded in the town. Motya had to subsidize his education by tutoring. He traveled to the villages as a home teacher there.

Even when we were students in the lower grades, we worked hard to maintain the Hebrew atmosphere of the school when our parents did not have the strength to oppose the change. The school was ordered to switch to Romanian from Hebrew by the authorities.

In the upper grades, many students left us. Some of us continued our studies at the university. Motya and others registered in the Hebrew teacher's seminary. It was called “The Language of Bruria” and was the equivalent of the Tarbut institute of Bessarabia. However, the majority attended the University of life. Others traveled far away to seek their fortune.

During the 1930s we abandoned our studies and joined the preparatory kibbutz to prepare for Aliyah. Motya made Aliyah, “five minutes” before the beginning of the war and the Holocaust, in 1939. We left behind families, parents, relatives, brothers, and sisters, and we were orphaned. Very few people survived the Holocaust and are waiting to make Aliyah.

[Page 650]

“Beit Neta” and its Director

G. Karsel

Neta Harpaz, z”l, was fortunate that while he was still living an institute for research into the struggles of the Jewish workers was established in Petach Tikvah. It was organized by the agricultural center and the Council of Workers in Petach Tikvah to research the situation of the workers in general, and in Petach Tikvah in particular. The person who created it, all alone, the center, as a beehive of varied activity was Mordechai Reicher. He died three months after Neta Harpaz. The man lived the dream of Beit Neta. He devoted his life to these activities whether in preparing exhibits or publishing tales of the struggle of the Jewish worker.

M. Reicher was the constant reminder of the chapters of the struggle that had been forgotten. He felt that they must not be forgotten. Proof of this can be seen in the numerous publications that he published. There was a new edition of the book “From a diary of a Bilu member” by Haim Hissin, “The Long Rut,” “Sixty Years Since the Destruction of the Workers of Petach Tikvah,” “Fifty Years since the Founding of the settlements of Achva and Avoda,” works about Michael Halpern, I.H. Brenner, and others. He was never lazy when it came to writing about the Jewish worker from the second Aliyah, and up to the founding of the State of Israel, especially in Petach Tikvah. I still have in front of me his letter in which he asks me to write about historic houses in Petach Tikvah, the mother of settlements.

The untimely death of Mordechai Reicher is a great loss. For that reason, the Council of workers of Petach Tikvah must fill the void by underscoring the person who supported others.

“Davar,” 13 January 1971. |

I can still see the valiant struggle of the few against the cruel authorities.

In Israel, he underwent many changes - as we all did. In the last few years, he was the director of the magnificent house - Beit Neta. It aimed to perpetuate the historic battles of the Jewish worker to become part of the land.

When Motya undertook his mission of running the house, he lived, with all his might, according to its purpose. He showed great initiative. He organized exhibits that brought back to life the stories of the labor movement and the country. He was also devoted to literary and historic work, and he researched the past of the settlement. He published many interesting books and essays.

In these books and works, he showed a pioneering ideology, something we are missing these days. These publications present interesting and educational reading materials and are recommended by the Ministry of Education.

[Page 651]

He proved his research ability and his knowledge of history in a large piece of work which is to be published in the Yizkor book for our Jewish community of Yedinitz. He undertook the job of editor, but he was unable to complete the task. For over 10 years he collected material and interviewed dozens of Holocaust survivors that had reached Israel. He was proud of his work and the great effort he invested in collecting the material, its editing, and putting it into the book. He added testimonies to testimonies, notes to notes, detail to detail. He scoured archives, encouraged people, demanded much of himself, and therefore, could demand the same of others. He found people in the country, former residents of the town who had arrived earlier. He communicated with former residents in foreign lands, and he was able to amass a large pile of letters, manuscripts, files of valuable papers, pictures, and documents. In the book, there is a section in which a historical overview is given, and it is entitled “The Martyrology of the Jews of Yedinitz.” It is a great literary piece of research that was written after much searching, interviews, and discussions, taking testimonies of dozens of survivors of the killing fields.

[Page 652]

A few weeks before he left us, he handed over the first pages to the printer – he edited, corrected, and abbreviated, them to give an accurate picture of our past.

He did not live to see the fruits of his labor. He was efficient in his work and disciplined towards himself and others. He made sure everything was historically correct. He was a good loyal friend, who inspired everyone around him with his good nature.

Fate did not spoil him. Part of his family was killed with other Jews in the Holocaust. Here he established a family together with Shoshana, his long-suffering and loyal girlfriend. They raised a daughter that was the pride of Shoshana and Mordechai, but she died a few years ago, still quite young.

When we look at the cruelty of fate, our expressions are weak: “We should not know any more sorrow.” What sorrow, you, our dear Shoshana, do you suffer? Continue, Shoshana, to be brave, in memory of Motya. We, his friends will continue his work to complete it, so that his name will be remembered forever.

* * *

[Page 651]

The Person with the Extra Soul

by Pinchas Mann

Translated from Hebrew by Ala Gamulka

|

His image excited my spirit even before I met him. I was a boy of 13. In the early evening, I used to sit in my parents' grocery store, and I saw him almost daily as he came up from the Tailors' Street with a book under his arms.

It was in the springtime when the snow was melting and mud covered the streets of the town, like a shining rug. One could only see the drying footsteps of passersby on the “sidewalks.” These were days of caressing sunshine from above and deep, slimy, and sticky mud underneath. I used to wonder how he kept the shine on his shoes, his shirts perfectly ironed, and his trousers clean without any stains. |

It seems to me as if he hovers over the mud. His appearance on the street negates completely anything in the surrounding area. It is like finding a holiday during normal days.

Later, when I used to visit him at his father's house, an impoverished man whose love of life and sense of humor allowed him to overcome his circumstances. I understood that his appearance on the street was an external expression of his fighting spirit. His spirit would not accept the actual situation and objective causes that were, seemingly, not to be changed.

[Page 652]

His yearning for change came from a deep rational conclusion that forced the change. It was a paradox in those days when the youth were excited by ideals. It was a time when the children of the town elders leaned to the left and became the leaders of the “proletariat.” He, the intellectual, perhaps the only one from the working class, was at the forefront of the national revival. The longing for change in his personal life and the lives of those around him was rooted and anchored in his being. It was more than just a speculative thought. Therefore, he was not enticed by the worldwide revolutionary movement which had lured many of the youth at that time.

Eventually, I was one of those who listened to the series of his reading evenings and explanations about “Dreamers and Dreams” by Yehuda Ya'ary. His deep voice, his self-identification with the images, the description of the background, and the scenery behind the actions of his heroes, created in me, slowly, the feeling that he was not just talking about them, but living with them and that he was one of them. Indeed, in Mordechai, there was a combination of dreamer and fighter, a believer, and an accomplisher. A few years later when I was with him in the leadership of “Gordonia” in Yedinitz, he was the gear in the machinery of all activities of the chapter. The period when he was in the leadership of the chapter was a time of growth and blossoming, a time of activities and programs which benefited from the dynamism of Mordechai.

His enthusiastic temper when it came to community issues, and his special ability to express himself, made him into the spokesperson of the young people. He was the main speaker on behalf of the youth at every meeting, be it under happy or sad circumstances.

[Page 653]

Even when he was elected to the top leadership of “Gordonia” in Romania, he still maintained strong ties with the youth of Yedinitz.

Mordechai made Aliyah in 1939. He belonged to the Avoca group. It was the second one after Masada (now in the Jordan valley) established by the “Gordonia” movement of Romania. The members of the group lived in a camp of shacks in Pardes Hannah. There, they worked as daily laborers in the groves and construction.

Pardes Hannah was then a young settlement founded by the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association. Most of the grove owners came from Germany, while the laborers were mostly immigrants from Poland and Romania. It was a community without any tradition or Jewish culture.

Soon after Mordechai came to the settlement, he began a vast educational program when he felt the cultural emptiness. The dining shack became a lecture hall, a place for evenings of reading Hebrew poetry, and symposiums on local and movement issues. It became a meeting place for the young workers in the settlement. With unrelentless energy, he brought in poets, writers, and famous leaders. Under his initiative, there were visits by the poets and writers like Shaul Tchernichovsky, Alexander Pan, Moshe Smilensky, Avigdor Hameiri, and the leaders Yosef Shprintzak, Levi Eshkol, Zerubbavel, and many others.

He developed this large cultural activity during a time of difficult personal absorption issues. He worked a full day in hard labor in the grove. It was difficult physical labor to which he was not used. His work in the movement did not even allow him to join the preparatory kibbutz, as did almost every other pioneer.