|

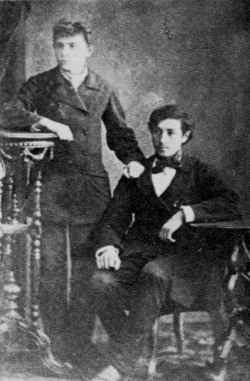

(winter, 1882)

|

|

[Page 224]

Hirsch Klein

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

Chaim Zhitlovski, one of the best-known representatives of Jewish thought, was born in the days after Pesach in 5625 (1865) in Ushacz [Ushachy], a small shtetl near Vitebsk. The family soon moved to Vitebsk. Chaim was then not more than three years old, and he remained in Vitebsk until 1886. Like all Jewish boys of that time, he first studied in a cheder and later at home with a rabbi. At 13, he entered the gymnasium.

In the gymnasium he began to absorb the ideas of Russian culture and the spirit of radical youth. In other surroundings and with a different education, this would surely have led to cultural and linguistic assimilation. Such cases were often encountered by wealthier families.

In his home, he only faltered in his younger years. But in that “warm nest, strands were spun in his soul” that “strongly bound him to the Jewish way of life, to Jewish people (his own people and strangers), the Yiddish language.” It is no surprise that his home had such great influence on him that he could never free himself of it. “In [our] home,” writes Zhitlovski in his memoirs, “there was organic, unified life…a Jewish life with a rich spiritual content. My father, our relatives, and our in-laws were scholarly Jews, and my father was known as an important Talmudist. The language in our house was always a rich, colorful, and ‘scholarly’ Yiddish–which I still use to this day! My father in particular always paid attention to the details of language. The dominant tone of life was an intellectual and spiritual tone for that era.”

[Page 225]

Later on, Zhitlovski lived in Vitebsk, which in his earlier years represented a “Jewish state.” Later on in his memoirs, Zhitlovski wrote, “If I had not known that in theory we Jews lived in exile…I would have been able to say then that I lived in a Jewish country, so little did exile play a role in our area, in Belarus, in the fifteen years–from 1865 until the end of the '70s…the Gentiles were a minority, and in the Jewish quarter where we lived–in Zaritshevya (Zarutshaya)–even a dwindling minority. Seldom did one see among the Jewish homes, at a street corner, an inconspicuous Gentile house, with an always closed section and locked doors…”

His home rather than his cheder established the foundation of his Yiddishkeit–admits Zhitlovski. His home exercised a Jewish influence. Although even then he was not observant, he gave a bar mitzvah sermon on a particular theme: “On which hand should a left-handed person lay tefillin.” The influence that the Hebrew and the Russian press, which could be found in his home, had on him combined with the work of his radical friends in the gymnasium. Russian language and literature assumed an increasing place in his life. He was pushed in this direction by his first friend from his gymnasium years, Niska Chaikin, and in his friendship with Shloyme-Zanvl Rapoport (Sh. An-ski).

“The Jewish State” was, however, not a strong draw for these young people, who were ruled by the general spiritual unease in Russia. Together with a portion of the Russian intelligentsia, the Jews were called to the demands for freedom and justice that they heard about in the radical journals of that time. They were also drawn to the theories of Lavrov and Mikhailovski, of Chernishevski and Pisarev, as well as the humanism of classical Russian literature. Like some of his friends, Zhitlovski could not resist the temptation and joined the movement for freedom that so magnetically drew the young people.

But after the horrors of the pogroms against Jews in 1881-1882, there was a break. The Jewish intelligentsia began to “come home,” and “The Jewish State” was revived, with

[Page 226]

|

|

(winter, 1882) |

[Page 227]

|

|

[Page 228]

its needs and problems. Zhitlovski, too, “came home, but his path was different.” He began to seek a synthesis of general social problems with Jewish national aspirations.

The truth is that Zhitlovski, as can be seen in his memoirs, never fully left his people. His grandfather, Shneour-Zalman, even had the idea that Chaim and his brother should go to Eretz-Yisroel, “buy” a colony, and live there forever.

Moyshe Zhitlovski, Chaim's younger brother, relates in his memoir “In my Parents' Home” several interesting chapters about their grandfather Shneour-Zalman and about his attitude toward Chaim.[a]

[Page 229]

In Vitebsk there were several active Narodniks: Lochow, Duchowicz, etc., and Chaim Zhitlovski moved in their circles and took part in intense revolutionary efforts. But his interest in Jewish dominated his world of ideas.

The summer of 1883 brought Zhitlovski to Ushacz. There he observed the Jewish ways of earning a living and the whole way of life, and they made a great impression on him, so that he left there for Vitebsk with a strong conviction that “I would no longer go into deep Russia..that all my plans and youthful fantasies about life as a ‘Russian’ among ‘Russians’ were all at once relegated to the background. In the foreground stood the Jewish problem, which appeared to me as a true sphinx: ‘Answer me or I'll throw you over.’”

And the thought came to Zhitlovski that Jews must abandon their old professions and the whole Jewish social-economic life must be rebuilt. And the thought of attracting the Jews to productive labor was paramount for him until the end of his life.

At that time Zhitlovski had the idea of starting a “Narodnik”-Jewish organization. Why did there have to be a specialized Jewish organization?

Zhitlovski explained the importance of such a Jewish organization: “First of all, it was a matter of necessity. We had to change over our economic life to the principle of agriculture. A Narodnik government would give us free access to the land and a means to organize the people according to the new socialist laws of the country. But not only from an economic standpoint but also from a national standpoint such a joining of movements was necessary.” It was decided, meanwhile, to put out an illegal journal, “T'shuas Yisroel” [The Salvation of Israel]. The plan and program of “T'shuas Yisroel” Zhitlovski presented to the executive committee of the party for its approval. The executive committee did not want to recognize a separate organization, and so nothing came of the plan.

Chaim Zhitlovski, however, had taken his thought further in regard to creating a “synthesis” between socialism and nationalism. Later this was one of the major labors of his whole life, but it is interesting that this idea came to him when he was

[Page 230]

no more than twenty years old. He then began to study Jewish history in earnest. In 1886, he went to Petersburg–and there he wrote his first work in Russian, “Thoughts about the Historical Fate of Judiasm.” This work appeared in Moscow in 1887.

Already in this work we find ideas that were dear to him in his later years. “Not the persecutions of Jews,” he wrote, “but thanks to the will in different epochs to fight in different ways for the existence of the Jewish people could they remain alive in the world.”

Zhitlovski's first work called forth sharp criticism, even from Shimon Dubnow in “Vochsod.” The young author who had such wide-ranging plans settled again in Vitebsk. The atmosphere in Vitebsk soon seized on him and almost totally swallowed him. Chaim Zhitlovski conducted propaganda in the revolutionary circles, distributed literature, and at the same time studied Marx and concerned himself with the ideological problems of the socialist movement.

In 1888, Zhitlovski left Russia. Shortly after, he established himself in Berlin together with his future wife, Vera Lochov. But Germany then was also dominated by anti-socialist law, and Zhitlovski was soon expelled from there. He then went to Switzerland, where he remained for about fifteen years. He studied in the universities at Zurich and Bern and there received the title Doctor of Philosophy. His dissertation was on historical philosophy, but also on a Jewish theme: “Avraham ibn Daoud (Rabad) and the Beginning of the Aristotelian Period in Jewish Religious Philosophy.” During his years in Switzerland, Zhitlovski also considered the Jewish question. A great clamor was caused by his pamphlet in Russian “A Jew to Jews,” which appeared in London in 1892 under the pseudonym I. Khisin. But his focus during the Swiss period of his life lay in studying the theoretical problems of socialism. As a follower of the Russian direction of subjective socialism (Lavrov and Mikhilovski), Chaim Zhitlovski came out as a consequential opponent of Marxism. On the national question, he stood near to the Austrian direction of Karl Renner, and in 1899, he

[Page 231]

published his most famous work, “Socialism and the Nationalist Question.”

But the focus of his work at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries involved the new Russian political party–the Socialist Revolutionary Party, which at that time began to organize. Together with his wife Vera, Charles Rapoport, Mendel Rosenboim, and others, Zhitlovski began to organize the first Social Revolutionary organization in 1893, the Union of Socialist Revolutionaries, which issued in Russian a small journal, “The Russian Worker,” devoted entirely to Russian socialist politics. Some years later, in 1898, Zhitlovski became the acknowledged theorist of the Socialist Revolutionary Party with the release of his huge work in Russian, “Socialism in the Battle for Political Freedom,” under the pseudonym S. Grigorovich. At this time, he published in the Russian legal journals “Novoya Slovo” [New Word] and “Russkoye Bogatsvo” [Russian Wealth], a series of critical works against Marxism, materialism, dialectic under the pseudonym N. Gadorov. In the student groups in Switzerland, Zhitlovski was well known for his lectures against Marxism and the Russian Social Democrats and for his discussions with Plekhonon and others. His talent for speaking resounded in the revolutionary circles in 1889 when his discussions came out under the title “The 72 Nights in Zurich.”

But all of this did not hinder Zhitlovski from immersing himself in the Jewish question. He studied Jewish history, the various national program of Jews, and all the modern movements. At that time, a number of basic principles of his outlook became stronger, and they remained the foundations of his later theories. The leading principle was that there was no contradiction between socialism and nationalism; and the second principle was that in order to strengthen the labor element in the Jewish people–the worker, the peasant, the laborer–a radical end had to be made of the social-economic structure in such a way that the character of certain professions for Jews had to be radically ended. This was the same idea that he had expressed years earlier. In his battle against assimilation, Chaim Zhitlovski came out as one of the most enthusiastic fighters for Yiddish. He would make no compromises on this issue.

[Page 232]

He defended the idea that “a national fight is a linguistic fight, that national equality means equality of languages.” His dedication to Yiddish was such that from 1904 he began to write and lecture exclusively in Yiddish.

It is interesting to note that his membership in the Socialist Revolutionary Party did not stop Zhitlovski from seeking a common language with the “Bund.” The Bundist memoirists (John Mill and others) relate that he even wanted to joint the “Bund.” But nothing came of that. In the Bundist journal “The Jewish Worker,” Zhitlovski published in 1899 a long article, “Zionism or Socialism” under the pseudonym Ben Ehud–an outspoken anti-Zionist work–and a critical notice about the journal “Der Jud.” A couple of years later, Ch. Zhitlovski became part of another circle of Jewish socialists who issued the journal “Vozrozhdenya” [Revival] (Ben Adir, M. Zilberfarb, Mark Ratner, and others), and later on he was associated with the Jewish Socialist Party (Sejmists), which the same group had founded. When the Sejmists in Vitebsk had put forth Zhitlovski as a candidate for the Second State Duma that was called for 1907, he came to his home town. But he had to leave quickly for Petersburg and a little later for Finland, where there was a meeting of the Russian National Socialist Parties.

Shmuel Zhitlovski, in his article “Memories of my Brother Chaim” (“Zhitlovski Collection,” Warsaw, 1929), has several sections on Zhitlovski's last visit to Vitebsk at the time of the election campaign for the Second Duma. “The initiative for the candidacy of Chaim Zhitlovski,” he writes, “was led by An-ski, who came specially to Vitebsk and led arrangements with the Jewish election committee. His candidacy was nullified, and people even wanted him arrested. He escaped from arrest accidentally because he had not spent the night at home but with Dr. Pollack. He was told what was happening, and he immediately left by post horse for the station in Horodok and from there to Petersburg. After the National Socialist conference in Finland, Zhitlovski stayed for a short time in Kiev, and from there he went abroad. The police annulled his candidacy.” Writes Shmuel Zhitlovski, “The famous lawyers, Vinaver and

[Page 233]

Maklakov intervened with the powers that be, but in vain: the government in Petersburg knew a lot about Zhitlovski's political-socialist activities over many years.”

In 1908, Zhtlovski traveled to the United States of America. He had visited America for the first time in 1904. As an envoy from the Socialist-Revolutionaries, he then accompanied the “grandmother of the Russian Revolution,” Catherine Breshkovskaya. He remained in the country for about two years and actually tasted for the first time in his life the diverse labors among the broader Jewish people. His life in America and the great success of Zhitlovski's cultural work in America over the course of ten years raised his greatest hopes, when he left Russia for the last time and sought for himself a new fatherland.

Ch Zhitlovski's activities in America developed greatly. As a writer, a publisher, a speaker, and popularizer, Zhitlovski took the top spot. From 1908 to 1913 he put out the journal “Dos neye lebn” [The New Life], which in 1922-1923 was revived with himself and S. Niger as editors. From 1914, Zhitlovski was a constant presence in the newspaper “Der tog” [The Day]. More than once he traveled through the length and breadth of America and Canada to lecture, and he made three lecture tours (in 1923, 1925, and 1930) in western and eastern Europe (Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia). For his jubilee, his followers issued special collections dedicated to him. Chaim Zhitlovski was never a practical activist, but many associations and movements nevertheless sought to use his name. Thus was Zhitlovski for a time the head of the council of the worldwide ORT organization. And thanks to the great influence of his ideas on Jewish cultural life, especially in America, we can note that “In America, Dr. Chaim Zhitlovski is undoubtedly the father of the Jewish-World School, earlier than the National Radical School, then the Sholem-Aleichem School, and finally the Workers-Circle School.”

Dr. Chaim Zhitlovski died at the age of 78 (in 1943) on a lecture tour in Calgary, Canada. His literary legacy was large and interesting. There is an edition of his “Collected Works.”

We must note, finally, that in the last years of his life,

[Page 234]

Dr. Chaim Zhitlovski was isolated from the wider Jewish environment. A large number of his devoted followers and students, who with great enthusiasm celebrated his sixtieth birthday (1925) and his seventieth birthday (1935), grew apart from their teacher and rabbi. About the last period of Chaim Zhitlovski's life we can bring a quotation that covers the sad fact, that “he, who spent his whole life fighting for freedom for the individual and for unlimited free thought, was no communist, but he allowed himself to use the communist commotion that surrounded him…” (Yudel Mark, “Dr. Chaim Zhitlovski–Collected Works.” CYCO, New York, pp. 17-18).

Original footnote:

Chaim Zhitkovski

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

1.

What I am giving here to my reader is nothing more than a page of memories, and also–certainly not in their full likeness. Many individual parts that are related to this matter sleep in the unconscious memory and will perhaps awaken later, when the concern for the present and for the future will–in a few years–weaken, and suddenly will begin to stir in consciousness clear images of the past, long ago times, as happens to people in old age.

Meanwhile, I will not delay; not only memories drive me on.

I know, in truth, that the history of that Jewish generation to which I belong, of that generation that had expressed in its heart and thought the synthesis of the general human program with a particularly Jewish national life, must be quite rich in interesting spiritual experiences; and if each of us could for a longer time immerse ourselves in the sea of memories, we would return with a treasure of pearls and coral that would of necessity have a tremendous cultural-historical and perhaps an aesthetic value; because our time, the period in which we grew up and have lived, has become the revolutionary period in the history of our people for the last two hundred years, both in life and in thought.

Also the earlier epoch, the time of the Haskalah, the fifties and sixties of the previous century, was revolutionary enough–in thought perhaps even more radical (in relation to its past,

[Page 236]

you understand), before the seventies and eighties, when we, the first progressive nationalists, had grown up. But the time of the Haskalah was a more critical period in thought rather than in life: the old religious and economic foundations of Jewish existence stood secure as a fortress, and only a tiny camp of revolutionary Maskilim used their strength and self-sacrifice to lay siege and heroically raise up those fallen in the siege. In our time, the fortress has been taken, the walls in many places broken through, and through those openings the wind, the rain, and snaky hands have increased the destruction.

The Chasidic foundations of Jewish life (at least for us in Lithuania) have begun to be rebuilt according to the blueprints of the Maskilim. From the stormy revolution in thought has come the quiet revolution of possibility. Haskalah, worldliness, menschlichkeit have become commonplace, to be met with in almost every Jewish home, even the most observant; “Ha-levanon,” “Ha-tzefirah,” and even “Ha-melitz” [Jewish newspapers]–pages that people read in Chasidic prayer halls. An ironed shirt with a necktie and short payes–these are no longer in contradistinction to the broad satin belt for Shabbos and Yom Tov; a game of cards and even an evening at the theater is no longer a sin, and a crumb is no obstacle to a fast, if it is conducted seriously and religiously.

What a wonderful pairing of cultural appearances that a generation earlier would never have been able to coexist! What a sweet-sour ideal of “faith” and “Haskalah” going “arm in arm, as the moderates among our Maskilim had fantasized!

And as the ideal became real in almost every Jewish home to a greater or lesser extent–deep in the Jewish atmosphere grew new spiritual storms--radical assimilation, the Chivas-Tzion movement, and progressive socialist nationalism that contradicted each other and took in everyone: the old Yiddishkeit and the Haskalah, and the radicals and the Chibas-Tzion.

A whirlpool of ideologies bound up with volcanic spasms in the ground led to earthquakes of catastrophic significance–these were the thirty to forty years of our lives in Russia, from 1870 until 1910. And parallel–a whirlwind of isolated images of life, which had

[Page 237]

never had time to become familiar, to reveal all their traits. First the momentum of Jewish life–or its quick dissolution–disrupted everything, as it would be disrupted and reborn and again disrupted, like the froth in a fast-moving stream.

No artist's hand could paint and color the fast movement of those pictures of life, because to paint them, the artist's eye would have to rest for a moment. But they were destined not to rest. Only isolated memories from each of us–however unartistic they might be–can pluck out from forgetfulness at least isolated features and moments of what our people went through. This has now become almost clear, as I have had to leave the sea of the past in order to discover there with some assuredness how and when I became a Yiddishist. A sea, a true sea! And if I do not want to be shocked by the spell of it, if I do not want to be afraid that it would draw me away from “today” and “tomorrow”, I would stay with it even longer. But it has drawn me more quickly back to current life and movements: consequently, I have had to leave many, many memories buried.

Yes, my current memories are not more than a page. But that word should not be understood in its usual chronological sense. The “when” of my becoming a Yiddishist can be pinpointed chronologically: the end of 1884 and the beginning of 1885. But the “how” was a longer and longer process that is lost in the gray fog of the Jewish historical past.

In order to be completely clear about that “how,” I must descend into my “personal” memories, if not to the time of “the destruction of Betar”–about 2,000 years ago–when the fate of our life in exile was decided and when, under the leadership of Bar Kochba, I fought against the Romans–at least until the 14th or 15th century when, with the expulsions from Germany, I made my way to Poland, bringing with me the “Jewish-German” dialect that there grew into its own language.

Unhappily, my own personal memories do not extend so far. The life of my previous incarnations–the whole history of the Jewish people that I have thoroughly studied with my angel, when I lay and grew under my mother's heart–is, thanks to the

[Page 238]

“touch on my lip” that the angel gave me before my most recent rebirth, erased from my memory. About the history of “Yiddishism” (as well as my overall Jewish nationalism), I must speak only on the ground of my own experiences in my current incarnation. And here I must bring to both a fact that had a great effect on both of them, greater than all the other effects of my life. This is the fact that I was born shortly after Pesach in 1865 in a Jewish home in a Jewish town, to Jewish parents who spoke the Yiddish language.

To this circumstance I give the greatest weight, and I would now beg the future historian of our generation, if he would seek an explanation for our nationalism, he would first consider the fact of our Jewish origin and keep it well in his mind. It seems to me that he need seek no other explanation: Our Jewish birth is the only, the natural, the true “satisfying reason” for our Jewish consciousness. He should seek an explanation for why our Jewish consciousness is so often darkened and blurred, so often almost suffocated in a hostile, foreign atmosphere..

I was born in a pure Jewish home; I lived my infancy and childhood years in a pure Jewish environment, and if I did not know that theoretically we Jews lived in exile, if I had to formulate my life experiences as they appeared from my first glances, I would have the right to say that I lived and grew up in a Jewish country; that is how small a role exile played in our area, in “Russia” (“Byelorussia”) in the fifteen years from 1865 until the end of the 70s.

The young Jewish commercial position, which at that time had begun to blossom, had established its own interesting Jewish life, full of internal spiritual power, full of its own energy. European civilization had already begun to cast its beams, which had in their own way broken through into the Jewish atmosphere and to spin together with the pure Jewish foundation into a unique, unified fabric. Such a pure Jewish life, where the Russian elements played no direct role, could literally–if people thought about it

[Page 239]

from the inside–call forth the illusion that we did not live in exile among the “Russians,” but quite the opposite, that the Russians, however much we had to do with them, lived in exile among us, in our Jewish land.

In any case–according to the internal experience of my early and later childhood years–nothing disturbed this illusion. People held that long ago the country had belonged to the Gentiles, but we Jews, as often happened in history, had taken it with our rifles and swords and so were, as was natural in such cases, the ruling people, if not political terms, at least in economic, national, and cultural terms.

The Gentiles were in our city, in Vitebsk–where my parents moved from the shtetl of Uszacz when I was about three years old–the Gentiles were a minority, and in the Jewish quarter where we lived–in “Zarutshevia”–a disappearing minority. Seldom among the Jewish homes, at a street corner, would one find a silent Gentile home, always closed up, with door shut, from behind which one would hear the grunting of pigs and the bark of a dog.

In our home, the enslaved Gentiles were represented–though not always–by “Nyesztser” the janitor (who at other times was called Andresz.), who tended our courtyard and cared for the animals in our barn, and from time to time would visit us. There was Yulke the washerwoman, who used to come once a month to do our laundry. She would sit there with her beautiful, wild, black hair, chatting with my mother and smoking cigarette after cigarette, while the “Sharas” (which in our area we called a cook who lived with her family in the home of her employer) and another Yulke, a Gentile woman “from the street,” would count out the laundry, throwing it in piles on the floor. There were the water carriers, who would quietly pour water from their pails and quietly put into their coat pockets the pieces of challah that they were given for Shabbos. There was the mailman, who would bring us a letter, take his four kopecks, sometimes sit by our table, when my mother would honor him with a glass of whiskey and a sugar cookie or a bit of jam as a snack. The other Yulke, whom I already mentioned, the Gentile from the street, was often in our house

[Page 240]

to help clean up, carry out the basins, wash the floors, milk the cow, and so on.

This Yulke was almost totally “assimilated” to the “ruling” people. She spoke the “ruling language of the country”–Yiddish–and actually a very fine Yiddish, with appropriately peppery words. She was often–I do not know why–in conflict with Nyesztzer and would not give him any leftovers. If someone asked her to give Nyesztzer something from the table or an old kaftan that would suit him, she would cry,

“Him? That drunk? That's a great mitzvah, like taking a dog for conversion!” (Nyesztzer did like his whiskey, but I have to say truthfully that he was no drunk.)

And around Pesach time when Nyesztzer would hang around in Sharas' room with his pipe a little too much, in the room where the Pesach beets were kept, covered with cloths, Yulke, washing the floor on hands and knees in the dining room, would shake her head and loudly exhort the Sharas:

“Look, look, Sossya! The non-Jew is there with the beets! He'll contaminate them with chametz!”

And even when Nyesztzer's name was not mentioned, he knew who was meant and would respond with an insult:

“What: chametz! Do I really not know?” And then he would end with a Yiddish curse, which in his mouth sounded like, “You should be hit on your head!”–which Yulke would answer with a sharp laugh…

…Ours was not a wealthy home. My father, a young lumber merchant, for whom things did not go badly, was no more than a well-off homeowner who had first worked for a wealthy man. But we also lived in that half-natural abundance of a medium prince in the city, for whom “his” courtyard reflected everything good. Also near our courtyard was a large warehouse full of all kinds of foods. There was port (wine) from Riga and a smoked lox (also from Riga) was hanging from the rafters. In wintertime, sometimes a sled would come to the courtyard bringing a sack with frozen fish, ranging from the tiny to very large carp

[Page 241]

and pike. My grandfather had bought a couple pood [a Russian weight equal to about 36 pounds] of fish from an Asian and sent them to us, announcing that he would be coming as our guest and that we should prepare for him milchik cabbage with fish, a meal that he dearly loved.

And another time, at the beginning of the winter, our hall was transformed into a workshop for furs and hides, where wolf, polecat, fox, sable, and squirrel skins were cut into linings and a town coat for my father and a fancy coat with a sable collar for my mother and fine furs for the children.

Actually not all of the “ruling people” lived in such comfort. There were also poor Jews–“perhaps” more than rich ones. Our family alone had a whole camp of paupers, both on my mother's and my father's sides. Our house was always occupied by one of our poorest relatives, and frequently by more than one. They would sleep on the “divan” and on wooden planks in the hall or the dining room or on stools that were pulled together. “Uncle Shloyme” from Eretz Yisroel spent a whole winter with us, always sitting on cushions on the divan in the hall, with his feet under him in the Turkish fashion. People at home were always talking about their needs and woes, or those of their relatives; who needed to get married and, in order to get a dowry, to open a shop or some other method. And I am sure that our house was in this area no great exception among all the others. Wealthier homes, where there were rich men or propertied home owners would have scores of poor relatives. And aside from their own paupers, aside from the poor “aunts” who “came without asking” and who reminded their richer relatives of the ditty “poor is not good, so let us not shame those of our own blood”–aside from them, there were loads of “foreign” paupers: workmen and laborers, teachers and sextons, luftmenschen little shopkeepers. And let us not forget the lazy ones [“shleppers”] in the literal sense, who would come to the house every Erev Shabbos, Erev Yom Tov, and Erev Rosh Chodesh. The door of our house was never closed: there was one group outside and one inside.

As it was with everyone at that historical period, so with us there were poor and rich: many paupers and few princes. But there was no class separation, no class opposition, and no class warfare. These only appeared later, with the development

[Page 242]

of the Jewish working class. People then could really talk about economic solidarity of the whole people, because the entire Jewish population–at least in our neighborhood–was a homogeneous, living organism…

The “illegal” guests who were to bring together the “T'shuas Yisroel” with the new executive committee of the “Narodnaya volya” [The People's Will] Party, soon after my being with them, left on a very long and difficult journey. We had to wait, because the answer from the committee would not come quickly. But I hoped that it would come in time, that is, when all the manuscripts were prepared for the first issue of the journal. But it came a bit later: only after almost year after our meeting, at the beginning of the summer of 1886.

In that same year, meanwhile, there were some important developments in my life.

My labors in the summer of 1885 followed the same lines as earlier, but more fervently. Their focus was on work for the journal. But now they could be conducted in more comfortable conditions, because in that summer almost no one from my growing family was at home. My father and my brother Boris were busy with business in Riga. My mother and, I think, my brother “Mutta” were in Dubeln, at the baths. At home were only my sister Rosa and her child. My grandfather was in charge, already a widower, who had earlier lived in a house with us over the courtyard and had now moved in with us. Strangers seldom came, except for Kolya, who came often. But he did not disturb my work. He would spend most of his time with my sister Rosa and with my grandfather. Who was he more interested in?–Who knows?

One time, in July, on a hot afternoon, I came home all worn out. No one was there. The door to my room was closed. I opened it and entered. There was a big box in the middle of the room, and my grandfather and Shloyme were packing up all my books.

[Page 243]

“What are you doing? What's going on?”

My grandfather explained that Lochov's sister (Vyera) had just been there and asked him to tell me that I should immediately clear out all of my illegal things (“treif things,” in my grandfather's words). During the night there would be house searches and they would certainly include me.

“I have no ‘treif things’! Shloyme, put everything back!” I said angrily and stomped out to the garden.

I actually did have more than a little illegal material, both mine and others'. But all of it I “hid” at Shloyme's. From there I came home, worn out, dragging myself under the baking sun. In my anger I was not sure what to do. Also Shloyme could not be certain if I had left anything at his place. And he did not dare to tell my grandfather where I had hidden the forbidden merchandise. So it was the smartest thing–to take everything down until my arrival.

I came back into the room and used a friendly tone to smooth over my unfortunate outburst.

Soon we sat outside to drink tea. Shloyme left, and I remained with my grandfather. As he always did when we drank tea, my grandfather looked in a religious text and in a secular one. After a little while, my grandfather laid aside his book and began to speak.

He liked Lochov's sister. “A very fine appearance.” And Nicolai Severianovitsch (Kolya) was also a very fine person. It was really a pleasure to spend time with him.

And suddenly he began to speak in a quieter tone:

“Do you think I don't know what company you keep? But this I do not understand about you. How does this fit you? You haven't lost hope…”

“What hope, Zayde?”

“To be redeemed from exile. I am sure that you haven't lost it. How does that line up with your efforts? Or…do you no longer believe in it?”

My wise grandfather had put his finger right on the center of the question that had plagued me for so long: Do they “line up”? And how could they?

I tried to clarify my standpoint to him.

[Page 244]

I had certainly not lost my “hope”. But people in exile had to redeem themselves. Naturally I do not remember the details of what I said that day. But I do remember well that I spoke bitterly about the Jewish ways of earning a living and about our economic role in the country, so harmful to the working masses. Thus I had to give my grandfather a bit of the “agitation” in the rules of socialism. I explained the moral foundations of socialism and why we had to suppress the notions of “mine and yours” that give rise to all the plagues and afflictions of all our lives. I gave a spirited description of the great accomplishments of the socialists.

Then we began an extensive discussion that I could not direct. I remember how in the middle of our discussion my grandfather cried out,

“They are coming to teach us justice? Us? They're going to tell us about doing away with ‘mine and yours’? Come here and see what the ‘Sefer Yuchasin’ [a history of the Jewish people until 1500 by Avraham Zacuto] says.”

My grandfather riffed through pages in the “Sefer Yuchasin” that he had been reading and that lay near him. I wonder now: was this a remarkable accident that my grandfather had just been reading the “Sefer Yuchasin”? Or had he intended to take this book in preparation for talking to me? But on the page that my grandfather placed before me was something truly unexpected, something remarkable.

The appearance of that page, with two columns in Rashi-script, is forever engraved in my memory. I don't have a “Sefer Yuchasin” with me, but I remember that what I had to read told how one Rabbi Zadok, from the School of Shammai, had established a fellowship called the Essenes who lived only by manual labor and who followed the principle of “one cashbox for everyone.”

Incidentally, the “Sefer Yuchasin” made a significant historical error: R. Zadok from the School of Shammai did not establish the Essenes but rather the Zealots. But at the time I had no knowledge of Second Temple history, and that historical knowledge made a deep impression on me. I kept looking at that spot that I read and reread. And my grandfather meanwhile explained the matter.

[Page 245]

“You understand?” Religious Jews…from the School of Shammai…from the most observant! And–one cashbox for everyone!”

For me, this was unexpected news! It was as if someone raised a little curtain that had blocked my view from around the world. But my grandfather continued to speak:

“And our prophets? Did they not care about the poor? ‘Ah, those who add house to house and field to field’ [Isaiah 5:8]. Have you forgotten? And in our prayers: ‘And they will make a single brotherhood.’ A brotherhood for the whole world!”

And after these quotations, he stopped. I looked at my grandfather's beautiful face with its gray beard, with its emotional, spiritual appearance. My grandfather was no “scholar.” In the end, he was a former confectioner, a working man. How long had it been since he stood with a white apron in his “workshop” and used his wooden implements to make a reddish mass for candies! But this lived in his soul! I sat there perplexed, digesting his words, which filled me with love and amazement for him.

Those quotations that my grandfather cited were not all new to me. Some of them I had known, though I had never really considered them, but none of them were as unexpected to me as the brief report in the “Sefer Yuchasin” about those religious-Jewish communists, the Essenes.

I allowed my grandfather to speak out. Then I came to myself and showed my “eloquence.” Yes, yes, these were all fine things. But! How do we live? What do we do? I was grateful that our Essenes already knew the absolute truth and tried to incorporate it in their lives. But what about the rest of the world, aside from them? And what do we know about their lives and aspirations. There is a difference between fine religious Jews, who believe in the justice of the socialist ideal, and the current socialists who are waiting for the “end of days,” when the messiah will come and will bring socialist justice everywhere; and meanwhile to live on the hard work of strangers is one thing, and to fight now with one's own strength for the actualization of justice is quite another.

And here the issue pairs well with my Yiddishkeit. The socialist party is a party for all people, including Jews. There must be Jewish socialists who will work among Jews, as Jews

[Page 246]

to the same end. And this Is what I have in mind. “They” cannot work among us. We have to do it ourselves. But in order to work for everyone's liberation, we have to work together with them. We cannot achieve liberation on our own.

Never before in my life had I spoken so openly and intimately. And never before was our love for each other so strong as it was at that hour when we ended, as the stars began to show and my grandfather rose to go to ma'ariv. Because of our discussion, he had missed mincha.

“Because of you, I will say two Amidahs!” he said in an accusing voice.

As he rose, he put his hand on my shoulder as if he were leaning on me, but I understood that that was a sign of love and trust.

I remained sitting there in an upset but exalted mood from this new experience. I was also happy with the discussion and with my sterling triumph.

I saw the high status of my grandfather, his dignity, with his payes and yarmulke, with his beloved appearance. And I thought: He is one of the best offspring of our people, in fact–the embodiment of our people, not preoccupied, not stained by buying and selling. Were we far from each other? I felt that basically my grandfather was in solidarity with me. Basically we two were one. We both had the same belief: the belief in a bright future for all of humankind.

And belief in our people then began to blossom in me.

But the story about the Essenes went deep into my being and awakened in me thoughts that even today are absolutely foreign to me.

Original footnotes:

Victor Tchernov

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

In Switzerland, where I hoped to find, according to an old tradition, the “heart and the brain” of the Russian Revolution, I found instead a weak echo. There were the autocrats of the social-democratic-Marxists, with their old motto about the “idiocy of village life,” which was like a submerged rock on which the Russian Revolution was constantly smashed. My perspective, which I was developing, was often regarded as an illusion, covered with the dust of generations. At first I was greatly disappointed. But a group of young students, my wife's friends, gave me great hope: in Paris, people would regard my plans differently. There they had a remarkable sympathetic person–himself a Jew, but with the soul of a Russian “narodnik” [Russian revolutionary intelligentsia], a student of Glyeb Ouspensky. His name was Semyon Akimovitch An-ski. One had to conduct a correspondence with him. I have to be grateful that I placed no great confidence in this. But then people delivered this news: “A letter from Paris! Semyon Akimovitch responded! He's coming soon to see you and to discuss things. Until now nothing has moved him like your concerns. He's traveling just to see you. He has a plan about that–about whom among the emigrants you can and should rely on; he knows the emigrants well. But he advises you strongly: until you are with him, you should refrain from whatever is decided, what could tie you down!”

It was easy to comply, considering the interest I had in meeting with him…

[Page 248]

When he arrived, he was a broad-shouldered, well-built man, with the muscled arms of a manual laborer; a broad face, solid and typically Jewish, with a slightly hooked nose, burning eyes deep in his forehead. His back was bent–because he was so bent over, one thought that his heart must also be bent. When he would contemplate something, his face took on a somewhat tragic appearance. Something was lacking in his face, and I thought: if he had a wide, grey beard–he would have the majestic appearance of a biblical prophet!

So what was this Semyon Akimovitch, and what was with that unnatural added name

An-ski! It turned out that his birth name was simple and natural–Solomon Rapaport! This was something else: he would have been a true Rabbi Solomon! But it appeared that aside from Rabbi Solomon, there was within him a mischievous little imp…

Usually when strangers meet for the first time, it is generally thought, they feel a bit awkward, not comfortable. But at my first meeting with An-ski I had no such feeling. He met with me like a total original and a clown…or like a mischievous child who was 40 years old! He was fully ten years older than me: born in 1863, and I–in 1873…

Generally when I have been with a new acquaintance, I have been fastidious about not being too familiar [literally “about not using the second-person familiar form ‘du’”]. But with An-ski, it seemed to come from him. I never noticed how it happened. He had such a character–an open, sincere, childlike, primitive approach to people; a bohemian, artistic nature, mobile, moving, expansive, he would charm you with his openheartedness. It would often happen–he would enter and begin to pour out sayings and anecdotes. He would laugh, and everyone had to laugh with him. Suddenly he would become a different person–he would sit quietly, contemplate. A strange sincerity would waft from him–from his deep eyes, sadness would appear, the eternal Jewish sadness, perhaps a reflection of that same Jewish sadness that his ancestors expressed, “sitting and weeping by the rivers of Babylon.”

And truly, people could well see in this, our new acquaintance, how rich the Jewish national type is with

[Page 249]

|

|

[Page 250]

inner contradictions and contrasts that appear in many ways. Endless sorrow and at the same time–a hidden lust for life shines everywhere with sparks of acuity and humor. Of all other national types, it is the most concentrated and peculiar–but at the same time almost them most cosmopolitan, with a spirit open to everyone; armored with sober realism and–dreamily exalted, almost fantastic; morbidly egotistical, but strongly inclined to laugh at itself, to make a joke of itself; it seems that every minute it is prepared to throw on its back a travel pack–spending its whole life dreaming of a new Zion; having the talent to adapt to strange fatherlands as if they were its own, and knowing no higher good fortune than “to die in Jerusalem…”

The figure of Semyon Akimovitch An-ski was original, and original was his personal fate.

Even as a young man, on the threshold of the 70's, he was drawn into the Haskalah movement, which led him to deny all of the old Jewish traditions, the old way of life, beginning with the family and ending in the beis-medresh. This was a kind of late French Voltairianism with a mix of local Russian nihilism. The role that the seminarians played in Russia in the 60's hit the yeshiva students in the Jewish world. Separated from the Russian language, literature, and knowledge by their Jewish studies, they were now drawn to them as to a forbidden fruit, mostly unknown to their parents. They studied the Russian language unsystematically, in a primitive way, simply repeating whole sentences from literature by heart, not understanding the meaning or misinterpreting it, speaking in such a way that true Russians could only understand them with great difficulty. In this way they would read Pushkin, study Pisarev, discussing them up and down, getting carried away with the naïve radical novels of Sheller-Mikhailov, held heated discussions over who was better, he or Dostoyevsky. This, as they understood it, they strove to incorporate in their lives, ripping those family threads that had bound them to the “old world” and trying to build a new kind of life…

Semyon Akimovitch used to say with a smile, “We lived, you understand, in a commune.” He added: “We

[Page 251]

were all equally hungry; none of us had a steady income. From time to time someone would give a lesson for a few groschen, a chance income; we might get a couple of rubles from the gymnasium treasury. For months at a time we would eat only bread and tea, and sometimes not even that. We regarded our poverty not only with philosophical scorn but with proud enthusiasm…”

All of this was in the spirit of the times. Semyon Akimovitch told me what he had personally heard from the well-known member of the executive committee of the “Narodnaya Volya” [a revolutionary socialist organization], Lev Hartmann, about that time in his youth:

“There were days when six of us lived in an apartment, but we had only two pairs of shoes. Four would stay at home waiting for a pair of shoes from someone who would return from the city; the two pairs of shoes served all six of us…We slept on the floor, with our clothing for a pillow, using newspapers for a mattress, eating black bread and sausage, drinking tea.” The leader of the commune distributed whatever personal items they had equally. “Chernishevsky's hero Rakhmetov (from his novel What Is to Be Done?) was for him a model to be followed,” he said, “by all propagandistic revolutionaries.”

In order to convince me completely, Semyon Akimovitch held up to me the memoirs of Panayev, how Nekrasov had lived in one small room with the artist Danenberg: the sun was their clock, they ate only a little borscht, had only a single pair of shoes, one overcoat for both, so they had to take turns going outside!…He himself, Semyon Akimovitch, needed no special “principles” for living such a life. It was quite simple–he was poor and never had anything better…

An-ski tried his luck at being a teacher. He sought students among the petit bourgeois elements in a small Jewish shtetl. But his heresies got in his way, his Gentile appearance, shaved beard–they frightened away the religious Orthodox element, which meant, if not everyone, at least the Jewish inhabitants of the shtetl. In one spot, people were so frightened of his Russian chrestomathy [reading list] that they called it a Christomathy and associated it with Christianity…People accused him of being a missionary, of wanting to convince his students to convert, and so on. A particular danger befell him

[Page 252]

when a young man from the shtetl's “free thinkers” took to reading Lilienblum's Khatat Ne'urim (The Sins of Youth), which was then the Bible of freethinking young people. The local rabbi, learning about this, was ready to call for his excommunication. By luck, Khatat Ne'urim was bound together with Gordon's Two Days and One Night, whose contents were completely innocent, in contrast to Lilienblum's heretical pamphlet, and the people who were seeking heresies were disoriented when the owner ripped Khatat Ne'urim from the volume and showed them nothing but Gordon's book, strongly demanding from the moralists that they should point out every unclean word about which they had complained. The moralists left in disgrace. People also found pages from An-ski's diary, where he clearly expressed his thoughts about the pogroms from the early 80's. People in the shtetl had said that the pogroms–were a punishment from heaven for the evil deeds of such Jews as Semyon Akimovitch…

This was the atmosphere that the young man breathed, he who had aspired to education and progress. It is no wonder that he did not last long; a new wave tore him away–“Going to the village, to the people!” His hope and expectation took him from the Jewish street to the broad plains of general Russian life. The grey everyday of the Jewish town he replaced with the mysterious half-darkness in the salt and coal mines…I must admit that he surprised me with this last feature of his youthful biography…

“Good,” I said to him. “You were drawn to ‘the folk’,” but “folk” in those years meant mostly–the village. The “folk” sit on the earth; where did you get the wild idea–to dig under the ground?”

His answer was simple: all the means and ways of disguising the propaganda in the village that were used in the 70's and 80's were well-known to the spies and gendarmes of the political police; to seek and capture revolutionaries who hid under the mask of a village teacher, a medic, a secretary in a government office, and the like were everyday matters. One had to find new techniques! And his trick worked: for the whole time that he worked in the mines, no one picked him out. He belonged to the dark mass of underground men. The whole

[Page 253]

character of such labor did not allow any thought about falsity, pretense, or disguise. During the time he lived in the shtetl, Rapaport, a Jew among Jews, people noticed him. He was the center of everyone's attention and suspicion; here it was the opposite. Among the coalminers he was left to himself. He abandoned his name and did not need a false pass. The miners were used to the idea that all those who had found no “path in life” would come to them.

…I saw in him a complete and perfect type of a Narodnik with a psyche not consumed by skepticism but hardened against it. Once I tried to ascertain from him whether being a Narodnik was for him a mixture of the Dostoyevkian and Rachmetovian, along with the Tolstoyan, and was that not a kind of ascetism, with self-inflicted pain? He protested strongly against this, but he could not deny it, since he emerged from his life as a caveman in the mines with weakened strength and with fewer teeth, which had fallen out due to scurvy.

“So I'm a Tolstoyan, a mixed up guy like Rachmetov?” he protested. “What would you say about the similar Lev Hartman? When he ‘went among the folk,’ one of the simple peasants perceived something strange about him and called out: ‘Hey you, monsieur!’” This caused an upheaval in his soul: he threw everything off and made of himself a true vagabond and went back to ‘the people’–a real beggar, a tramp. Today Pavel Borisovitch Axelrod? He would search in Podolya Gubernia for a legendary robber who would share among the poor people what he stole from the rich; he did not find this thief and began to preach that all Jews should return to Palestine; who would have expected this from a futuristic Marxist? And Lev Deutsch? He was brought up because of Karakozov's attempted assassination [of Czar Alexander II]. Really, an assassination attempt on such a good czar–that's a crime!” And later on, when he had lost his “czarist” illusions, he was not long full of anger and sorrow, because the Russian and even the Jewish socialists had taken to “fighting for a constitution for the Warshawskis, Brodskys, Poliakovs, Ginzburgs, and their like.” And let us consider Aptekman. In order to mix totally with the “people,” he totally gave up himself, as if he would

[Page 254]

torture himself, he went ahead and converted! No, no one found crazy behavior in me, but in our whole generation, not omitting those who are considered masters of positivism and objectivity!

After these two periods of time–as a teacher and a mine worker–there was a third for Semyon Akimovitch: as a literary man.

He became a writer by accident; his talent as a writer was revealed by another well-known Narodnik who also came, like An-ski, from the Jews: Grigori Ilyich Schreider. Later, after the 1917 revolution, he was called from our party to the honorable post of Petersburg city president (“golova”). At that time he was already the chief editor of our provincial newspaper, “Yug,” (“South”) in Yekaterinoslav. He had a rare talent as an editor and was interested in a modest article about the life of mine workers that was written, so he believed, by one of the workers. He sensed in the author an artistic nerve, and he decided to become personally acquainted with the author, so he called him in and said something like: either he, an old literary man and editor, knew nothing about literature, or Solomon Rapaport, a born writer, did not understand what a talent he had. He must have a good teacher from among the true, already developed, talented writers. Better than anyone else would be such an appropriate teacher as Glyeb Ouspensky. And more than anything, he had to immerse himself in the atmosphere of great Russian literature in the capital. He, Schreider, could give him a recommendation to Ouspensky and to the editors of the Narodnik monthly journal, who gathered around N.K. Mikhailovsk himself.

Semyon Akimovitch was seized by this head spinning perspective that had opened for him. He was nervous, he trembled, he was resolute and then not so resolute. He saved money for the journey. There he developed the attitude, there he strongly believed in himself as a future writer, there he became disappointed in his craft. Finally, his fate came to pass.

In Petersburg, An-ski, right from the train station, went in the evening for a friendly glass of tea with the literary headquarters of the Narodniks. There were the best of the Petersburg Russian intelligentsia. There, too, was the literary foundation of the

[Page 255]

underground revolutionary movement. And there, too, was Glyeb Ouspensky. He read the recommendation and made his way over to An-ski with enchanting friendliness; but he soon went away–he had a family celebration for a close friend. He went there, perhaps to stay into the night; but he goes there in order not to miss the regular weekly meeting of the fighting group. Without him, Semyon Akimovitch turned into a jellied “dumb figure.” He picked up every word of those who were there. They were all “light spirits!” He did not notice how the evening passed. At midnight, people began to get ready to leave. People said good-bye and went home. Home?! Semyon Akimovitch until that moment had not given a thought as to where he would go. He had no relatives there, no acquaintances. In a hotel? He had no permission to stay there. He had no one to ask for advice. Glyeb Ouspensky, to whom Schreider had recommended him, was gone; everyone else he did not know: they were the editorial board. Should he tell any of them about his predicament? The thought alone made him go hot and cold. Having come to no conclusion about what to do, he automatically did what everyone did: he put on his coat, said goodbye, and went out–out to the empty streets of the strange, unknown, big city.

What should he do? He went, went–from one street to another, from one boulevard to another. He lost his directions and soon did not know where he was. His tired feet carried him here and there on the boulevard, where the benches tempt him to sit down. But he has not yet sat down and started to dream when at a distance appears the figure of a policeman. He has to spring up and appear as an untroubled wanderer out for a walk. So passes hour after hour. The night is fearfully long! Suddenly–a familiar figure appears near him. Yes, there can be no doubt. It is Glyeb Ouspensky! He has left his meeting that was like a family celebration and is probably on his way home…Ouspensky looks at him with amazement. He recognizes the “writing colleague of the mine workers” and begins to inquire what and whom he seeks so late at night, nearly at dawn?! An-ski cannot keep his secret. And now Ouspensky sees with his own eyes the mournful, humiliated, tragic results of the requirement that Jews have a “residency permit.” He has heard about this many times; now before him he sees the bloody injury.

[Page 256]

Ouspensky takes Semyon Akimovitch by the hand, brings him home, drinks tea with him, puts him to bed, and sits at the foot of the bed: he will know in all its details the naked truth about the life of the Jews. Semyon Akimovitch talks and talks, not noticing that from fatigue he has begun muttering nonsense, rambling–and he falls, probably, into a deep, if short, sleep. Something disturbed him and he quickly awoke, but he could not tell where he was or what had happened to him. He looked around the room…at the foot of his bed, quiet as a statue of unending sadness, sat Ouspensky, contemplating, beaten down, as he himself had appeared when he was first questioned. From his eyes descended a single large tear…a second…a third…

The Jewish-Russian Encyclopedia of Brockhoyz-Ephron correctly describes a whole period of An-ski's work, the period between 1886 and 1892, whether thematically or philosophically, as “under the strong influence of Glyeb Ouspensky.” The extreme subjectivity that suffuses Ouspensky's work on public affairs with nervous excitement, always shocked An-ski. This recognition on the artistic front in the work of his beloved teacher led him to see “a distant flash that revealed the coming storm of psychic illness.” And he carefully worked out a precise restraint in “pure storytelling art,” sometimes even allowing a light tone of good-natured humor–and occasionally a sharper irony. And like Ouspensky, he was dominated by a specific kind of writerly modesty.

“You know, Victor, what was hard for me at the beginning of my writing activities? You could never guess: it was, how should I sign my work! I was embarrassed to sign my own name. I understand Turgenev, Pisemsky, and Ostrowski–people know what kind of spiritual food you get. In literature, this is like a firm in business. But what will I evince with a Solomon Rapaport, that says nothing? For me it was a real relief when I was told that one could use a pseudonym. But a pseudonym has to be carefully considered, and I was not capable of such thought. Finally, I was helped

[Page 257]

by that same Glyeb Ouspensky. He worked and worked with me, finally took pen in hand, and wrote the initials of my name under the article about the life of mine workers: S.A., then An…he thought for a bit, wrote a hyphen and then added “ski.” “Do you like this?” he asked. I was quite happy. It really pleased me: probably because he wrote it himself. From then on I was S.A. An-ski. Glyeb Ivanovitch gave me the first lesson on how to write fiction. He also gave me a literary name, and finally he gave me the idea to travel abroad, once and for all to shake off–as he expressed it–my Jewish, as well as my Russian, provincialism. And finally–he arranged for me to be a personal secretary to Lavrov in Paris.

If Glyeb Ouspensky long reigned over Semyon Akimovitch's heart, Lavrov disciplined his brain and raised him to the highest levels of human knowledge. When Lavrov died, I got the feeling that the spiritually orphaned Semyon Akimovitch transferred his whole attachment to me.

At first glance, superficially, I could have thought that Semyon Akimovitch was a completely denationalized Jew. That this impression was false appeared only later. Although he had undertaken to master the Russian language late–at 16 or 17–he loved Russian literature so much that he read it, thought about it, and felt it, so that the Russian language became for him for than a “second mother tongue.” Yiddish and Russian were not for him a first or second language but “two firsts,” and they competed in advancing his spiritual life, now one and now the other, depending on the circumstances. It is characteristic that he himself did not like translating his own works from one language to the other (although Nekrosov, for example, and Nikitin he translated into Yiddish). Despite the many requests that came to him, he did not translate into Russian the remarkable poem “Di shvue,” which was the anthem of the “Bund.” Incidentally, that this anthem was a creation from the muse of the Russian writer An-ski, only a few of us knew for a long time, mostly editors of encyclopedias.

[Page 258]

When I met An-ski for the first time, he instinctively emphasized how he had shaken off the Jewish national element that had lay hidden in him. At first I could not understand this; but I quickly came to understand from “The Wind Blows.” Semyon Akimovitch was influenced by the voice of Pyotr Lavrov.

An-ski looked on the revival of the Second International as something inevitable, but not as a successful compromise for the spirit of the times but as a partial capitulation of internationalism to nationalism. I discussed this with him fruitlessly, showing that sometimes people have to withdraw in order to have a place from which to proceed. Otherwise it is not possible to take a bigger step forward. An-ski regarded this as sophistry.

One time our discussion intensified because of the following: in London, a Yiddish group was established that undertook to distribute socialist literature in Hebrew. They came to Lavrov (as did the Agrarian Socialist League later on). They wanted his blessing for their project. But they found no sympathy from him. This did not mean that Lavrov was not someone who promoted “Yiddish.” According to the general publication that I received, he regarded Yiddish as a “jargon,” a crippled German, and he regarded Hebrew–as a Jewish Latin. According to him, neither language lay on the broad road of Jewish cultural development. They were both side roads. A logical deduction, then, would be–a categorical demand that Jews should be linguistically assimilated. But Lavrov did not make this logical deduction. He saw–correctly–the spiritual rape of a small people that had a rich history. There remained an unresolved contradiction that became even more difficult for his true pupil and personal secretary, An-ski.

One time, Semyon demanded from me a categorical response: How would I resolve the contradiction? I answered briefly: Wherever Lavrov said no, I would say yes. The Second International marked not regress but progress in comparison with the First. Without going through the phase of “national self-expression” of socialism in the conditions of

[Page 259]

of every country, the International would be a house of cards. Jewish socialism must go through its period of “nationalization.” The battle between Hebrew and Yiddish makes the matter more complicated. But what can one do? Perhaps they both have a foundation, one for the Ashkenazim and the other for the Sephardim. One for Central and Eastern Europe and the other for the Asian Near East and the countries of the Mediterranean that are bound to it? If the Jews want to return to their former Semitic environment, Hebrew should be called for. If such a return is unsuccessful, then Yiddish should remain the cultural ruler. I should not mix into such a conflict. This is an internal matter for the Jews themselves. Semyon Akimovitch was not happy with such a solution to the problem. At that time he was under the influence of Zhitlovski, who had altogether discarded Hebrew and focused on Yiddish.

I do not know how long the doubts and hesitations would have lasted for Semyon. But then new things happened that made a strong impression on him and changed the course of his “Yiddish” thinking. There was the second conference of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers Party. At this conference, the Russian Party, whose rise was greatly indebted to the “Bund,” did not agree to give the latter full autonomy in the structure of the party, about which they had earlier had a long discussion. An-ski was totally on the side of the “Bund” in this controversy. I also agreed on general principles with An-ski, although in a more Platonic way, that is to say, as a bystander, while he felt like a Bundist patriot. As I have already said, An–ski, as well as his friend Zhitlovksi, was affected by an impulsive young man who lived in Bern under the name Isaacson: this was the later well-known worker in our socialist surroundings Liber Goldman, who ended his life shortly before the Second World War in a Soviet prison somewhere in middle

An-ski became bored by the fruitless efforts to bring him into the “Bund.” He was also urged by the initiatives of the old Narodnik Volkhovskoy–a Ukrainian by origin–to publish in Ukrainian his own fictional folk story

[Page 260]

“The Wrongful Czar,” and in general he began to work on creating a fund to publish essays in Ukrainian. With my whole heart I welcomed such an initiative. When the announcement about this appeared in “Revolutionary Russia,” Semyon rushed to me all excited: “Why should the party not establish such a fund to produce literature in Yiddish?”

“This is because,” I responded, “our Yiddish writers are good for nothing: They don't do in their area what the unique Ukrainian Volkhovskoy does. In other words–more than anything, this is your fault as well as Zhitlovski's.”

“Because of us there would be no obstacle, but we must know how the party would react to it?”

“And I will tell you: the party would create no obstacle. So don't sleep. Get to work.”

Semyon really took off with this concept…and the work went well. In short order we produced three or four Yiddish anthologies.

At that time the revolutionary events and also personal circumstances separated us for a long period, put us on different sides: I wandered abroad as an emigrant while he determined “to stay at home,” on the basis of legal existence. We encountered each other again during the revolutionary conflagration of 1917-1918. One time I received second-hand news about him. One of our party members, M.A. Levin, told me that he encountered An-ski in Vilna. That was in 1909-1910. He was giving a lecture there about Yiddish literature–this was after a long pause–at the first meeting of the local Jewish community with the popular writer. He was treated as a celebrity, with welcoming speeches. As if answering these greetings, An-ski spoke in the language of a penitent. He asked forgiveness for having devoted himself for so many years to the “Gentiles.” He explained that even in those years, when he had such little connection with the Jewish community, he never lost interest in the Jewish folk spirit, which lay so deep in Jewish folklore. (This was true, and for his later famous work “The Dybbuk” he undoubtedly received

[Page 261]

stimulation and prepared himself thanks to his research and exploration in the area of Jewish folklore.). Unfortunately, his usual impressionism, that was so typical of his way of thinking, gave certain members of his audience the impression, that he regretted the former period of his life. This was a mistake. As one could understand, his regret belonged to the period of his life before the rise of the Socialist Revolutionary Party and probably also at the beginning of its rise, when he was ruled by abstract “cosmopolitan” internationalism; this had blocked for him the perspective of socialism, which was in the flesh and blood of Jewish national life and culture. Even in the Socialist Revolutionary period of his life, An-ski found this perspective and for the first time tried to work in its light. This accords with the entire following political story of his life.

In 1917, during the elections to the Petersburg city council, he was a candidate from the Social Revolutionary Party. He was then a steadfast and convinced Socialist Revolutionary; he then bore a new idea (new for his fellow councilmen, but not for me)–to create a separate Jewish party that should have in spirit the same aims as the Socialist Revolutionary Party, as had the “Bund“–with the Russian Social-Democratic Party. He held that since the purely industrial Jewish proletariat was very small and was bound up with the “little men” who were artisans with the half-proletariat from the business- and middle-classes, only the Socialist-Revolutionary Party has the strength to give Russian Jewry a broad “workers” program instead of the smaller, foreign uniforms in which, according to him, the orthodox and “industrial-centrist” Marxists had stuffed the Jewish body and the Jewish soul…

Another time in the list of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, Semyon was in the Constituent Assembly. There he was anxious about the fate of the Jewish question, over how much it would appear in the Constituent Assembly. He spoke with a whole array of Jewish deputies about issuing a special Jewish declaration. He did not come to speak to me about this matter. With great excitement he listened to my opening speech as presider. That, when I was later told about the impression that he took from my speech, forced me not long afterwards to search in the New York Public Library, where I

[Page 262]

sought a rare document–the stenographic report of the first day of the founding assembly (Petrograd, 1918). About the civil war that began with the Bolshevik revolution and that brought a clash between different national groups in Russia I said in my opening remarks:

“Just the fact that we are opening a Constituent Assembly proclaims the end of the civil war among the people who inhabit Russia”; there can no longer be any fear that “the hand of a Russian soldier, a peasant in a gray greatcoat, should rise up against a Ukrainian peasant, who also wears a gray greatcoat (applause from the center and right, voices saying ‘Long live Ukraine!’). As long as the Constituent Assembly is the highest power in the republic, both the Cossack-laborers and the children of those who are free be sure that their right and freedom are in no danger from a Russian soldier”…“The Muslim population–whether concentrated in one territory or scattered like a national minority–can expect that the Constituent Assembly will recognize their sovereign rights, like those of any other nationality.”

“…And finally, citizens, allow me to say about that ‘stepchild’ people, that people that has been persecuted more than any other, that people that has been a scapegoat for exploitation by the whole world, the people others have tried to blame for the misfortunes and sorrows of the working masses, in a way that would be permissible for no other people, because in all peoples, without exception, the working masses are the far greatest majority of the population. And the Jewish people, who did not have their own territory, should have, within the boundaries of the Russian republic, the same rights as all other people to establish their own national self-control and to express their the will of the working people!”

Having heard this speech, Semyon said: “No other special declaration about the Jews is necessary. All that we need, all that concerns our rights, has been said–said openly, categorically, so that nothing more is needed. The project of my declaration I now put away into my archives.”

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Vitsyebsk, Belarus

Vitsyebsk, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Jun 2025 by JH