|

|

|

[Page 1]

by Yeshaya Trunk

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

The city of Vitebsk, which experienced during its history many political-territorial changes, is first mentioned in sources in 1021. It was then the capital of the Vitebsk principality. After many wars between the Vitebskers and the Lithuanian princes, the Vitebsk principality was finally incorporated in 1320 in the Lithuanian kingdom. In 1511 or 1514, Vitebsk became the administrative center of the Vitebsk voivodship in the united Polish-Lithuanian kingdom.

In 1772, after the first partition of Poland, Vitebsk was unified with the Russian Empire. At first the city belonged administratively to the Pskov gubernia. In 1777 it became part of Polotzk gubernia. In 1796, Vitebsk became the administrative center of the White Russian gubernia. In 1802, the White Russian gubernia was divided into the Mohilev and Vitebsk gubernia, though they maintained the prior name (White Russian). Only in 1840 were both gubernias called by the names of their administrative centers. This was their last administrative-territorial transformation.

Jews are first mentioned in Vitebsk in 1551. In that year (November 27), the Polish king Sigismund Augustus, who was simultaneously the Lithuanian Great Prince, ordered in a session of the Sejm in Vilna the compilation of a list of all royal cities and towns with indications of the amount of the “Serebshtshizna” tax.[1] This shows that Jews and villagers were exempt from this tax. Vitebsk was among the 15 cities that

[Page 2]

were on the list.[2] Can one therefore infer that Jews already lived in Vitebsk in the 50s of the sixteenth century. This document provides no absolute certainty, given that it could mean that what applies to Vitebsk is not true for the villages that inhabited city or suburban areas.

But other documents show that Jews already lived in Vitebsk in the middle of the sixteenth century:

Rights, which said that Jews must not, in accordance with an old custom, have the right to live in Vitebsk.[7] But this cannot serve as evidence, because Jews had earlier, before 1597, not lived in Vitebsk and even less does it show that after 1597 Vitebsk did not have within its borders a Jewish kehillah. First, the matter about Jews was not promulgated in the form of a command but rather as a recommendation for the future.[8] “Jews,” says the privilege, “should, according to the old custom, have no right to live in our city of Vitebsk.” And what is the meaning of “according to the old custom”? One must assume that this passage is more of a theoretical-juridicial statement than a factual one, that is to say, that the Magdeburg Rights in general limited the Jewish inhabitants of the city. We see this also in the example of Mohilev. When Stefan Batory in 1585 extended the Magdeburg Rights to Mohilev, he also in the privilege established the rule that Jews had no right to live in Mohilev.[9] But there this principle had no practicality, and in 1633 a Jewish quarter was first established in the city. (Until then, Jews lived anywhere in the city.). In addition, the Magdeburg “letters” for Polotzk had limited the local Jews as far as building and buying new houses.[10]

As clear evidence of how little the Royal Privileges of 1593 affected actual lives, we can cite the matter of “Yoridikes”[1]. The same Privileges prohibited the existence of Yoridikes in Vitebsk; but the Yoridikes were not only not nullified, but for the first time they increased. Even the Vitebsk Privilege of 1597 made an exception for the time of the annual fairs that lasted for four weeks. During the fairs, all the restrictions on entering and doing business in the city were suspended. This exception to the rule was in many cities the weak point thanks to which Jews could enter the cities and create a foothold outside of the times of the fairs.

From the available documents, one can with absolute certainty establish that:

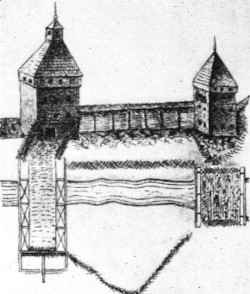

Where was the oldest Jewish quarter? Old Vitebsk lay between the shores of the Vitba-Dvina and Rutshayev. Later on, the city built on the right side of the Vitba, where the market was located in the seventeenth century, as well as the shops, the warehouses, the city hall, and the church. This oldest part of the city was called “Zarutshevo” (Zarutshaya) and lay on either side of the Rutshayev River and was already built in the sixteenth century.[11] There, in that area, was the oldest Jewish quarter.

In an inventory from 1655, which indicates the topography of the city and the castles, we read: “From the Zarutshaya Tower until the Jewish Tower–a wall of 68 saszen [a Russian measure equal to about 2.5 meters] of cut stones.” A second inventory from ten years later (1665) connects the “Jewish towers) with the “Zarutshaya Great Passageway.”[12]

Over the course of time, Jews spread into other city neighborhoods. In this respect, the Jews of Vitebsk, as it appears, encountered no legal obstacles. In the mid-seventeenth century (1641), they occupied in Vitebsk about two-thirds of all the houses and squares (652 out of 1010)[13]. Why a writer in the city in 1641 recalls not a single Jewish house remains the secret of that writer.[14]

[Page 5]

From 1654 we have clear news that a Jew was the owner of a house and a square in Vitebsk. On May 28, King Jan Casimir assented to the request of a priest to take for a church the house and square that had belonged to the Jew Mordechai, who had died in Moscow.[15]

From the eighteenth-century sources we gather that transactions involving houses and squares between Christians and Jews were common. So, for example, in a list of sold real estate that the Vitebsk sub-commissar Adam Kishel in 1719 gave to the elder of the Bazilian Monastery, there is mention of a square that he had bought from the Jew Shloyme for 200 thalers.[16] Two years earlier, the Vitebsk castellan Martshin Aginski gave to the brotherhood of the Petropavlovsk Russian Orthodox Church Telutin Square, where formerly the Jew Shelmovitch (Shlomovitch?) had lived.[17]

On the other hand, Jews freely bought places from Christians. In 1750, the Vitebsk councilman Tom Lawrence entered in the city books that the Vitebsk kehillah had bought a place for 25 thalers. That place was in the district “Izgorovo” on Padtitshinsk Street, behind the Sposk Church.[18]

In the Vitebsk kehillah record book, there are relatively often descriptions in the eighteenth century of Jews buying Christian houses. The kahal would conduct these transactions and register them in a special “record book of possessions” at the Beis Din of the appropriate city quarter (Zadunovia, Zarutshaya, and so on). These cases are found probably in connection with the fact that the Lithuanian-White Russian kehillahs received in the seventeenth century the privilege on the non-toleration of Christians, that is, that Christians dared not buy or rent houses and places in the Jewish Quarter. If, due to non-payment of a debt or for some other reason, a Christian came to own a Jewish house or place, the kahal had the right to force him to sell it to a Jew.[19]

The wars with Moscow in 1654 and with the Swedes in 1708, as well as the frequent fires, more than once destroyed the Jewish quarter. Especially terrible was the fire at the time of the so-called Northern War (1700-1721), when the Russian captain Soloviov in September of 1708 burned down the entire city because Vitebsk sided with the Polish crown pretender Stanislav Leshtshinski, who supported the Swedes against Moscow.

About the frequency and range of fires in Vitebsk, one can be

[Page 6]

convinced by the fact that in the course of 15 years (1752-1767) there were four great fires (two in 1753), and in the fire of 1762, about 800 houses were burned.[20]

These catastrophic events surely caused a portion of the Jews to leave the Jewish Quarter and to gather in other areas. But the sources do not show this exodus. We only know that around the middle of the eighteenth century Jews were settled in the “Isgorovo” area, where they had not lived until then.[21]

|

|

The legal situation of the Jews in Vitebsk until its incorporation into czarist Russia in 1772 was the same as that of Lithuanian-White Russian Jews in general and developed as a

[Page 7]

|

|

result of two opposing tendencies. On one side people strove to limit the rights and freedom of the Jewish population in various areas; and on the other side, in contrast, in the name of well-understood private or government interests, people welcomed their legal situation. These two opposing tendencies were mainly dictated by the economic interests of the social classes to which the Jews were economically bound.

The most consequential social supporters of the first tendency were the city bourgeoisie, whose hatred of Jews was aroused by economic competition. Later on we will see how the people of Vitebsk fought with the Jewish population.

The great magnates, on the contrary, because of their economic interests over all, took the side of the Jews in this battle between the Jews and the others. The Jewish leaseholders and innkeepers brought

[Page 8]

capital into their backward, feudal agriculture, and Jewish merchants exported their agricultural products into broad internal and external markets; and they also imported goods from European markets at lower prices than did Christian merchants.

Contrarily, the middle and unpropertied classes looked with unconcealed jealousy regarded with jealousy the firm economic position that large Jewish merchants held in the upper-class economy and their incomes, which greatly troubled them.

The royal authorities took a wavering and inconsistent stance in this opposition between two social-economic forces. This stance was the result of the impossibility of making peace between two opposing interests: for the royal treasury, the legal and successful merchants and lessors were a source of great income, on the one hand; and on the other hand, the townspeople and the unpropertied classes felt the weight of the rivalry with the Jews. For those whose interests at a given moment had the upper hand or were decisive, it depended on whether or not the royal government would support the rights of the Jewish merchants, lessors, and craftsmen.

As we have already seen, Sigmunt III had submitted to the demand of the Vitebsk populace and agreed to their demand to take from the Jews their right to live in the city. Sigmunt III, who at that time had great plans to take Moscow for his dynasty and to win over the Russian population to Catholicism, wanted to gain favor with the White Russian Orthodox citizenry with his anti-Jewish orders. His son, Vladislav IV, led a smaller Catholic dynasty and had more realistic politics, dictated by concrete interests of the kingdom. So he legalized in 1633 not only the legal status of the Jewish kehillah in Vitebsk, but also gave the Jews all the rights and freedom of the general privileges, in which he particularly stressed the rights of free economy as well as the jurisdiction of his highest local offices–the voivode–over the Jews of Vitebsk.

The war with Moscow in 1654 severely undermined the economic situation of the city. The Jews of Vitebsk returned from their

[Page 9]

captivity in Moscow with great losses of people and property. The city could only very slowly and with difficulty recover from its poor situation, so that the populace did not maintain their battle with their Jewish neighbors and did not oppose the strivings of the Vitebsk Jews to reestablish their rights over their stolen property, in whose theft the townspeople had played such a big part.

At first the king, Jan III Sobieski, who had generally dealt liberally with the Jews, in his Privilege of March 16, 1679, restored the old rights of the Vitebsk Jews, emphasizing that he did so “in order to restore the city to its former wholeness,” which was destroyed by war and plague, and to elevate its situation by relying on people who were experienced in commerce.

In this detailed Privilege, the Vitebsk Jews were permitted: 1) to build various buildings for their private and religious needs; 2) to have butcher shops and to slaughter animals for themselves or to sell, according to the rules of shechita, and they did not have to the guild of butchers; 3) in order that the city should not decline but should, on the contrary, enrich itself through commerce, the Vitebsk Jews were allowed to deal in open markets with “colored goods” (textiles, leather), iron, fabric, pelts, footwear, baked goods, alcoholic beverages, expensive goods, and other things, paying business taxes like all other citizens; 4) they were allowed to take part in all other professions and have their own barbers; 5) their exclusive judge would be the voivode and they had the right to appeal his judgment to the royal and tax courts.

This “Magna Carta” for the Vitebsk kehillah was confirmed by August II on October 7, 1729, and by August III on August 13, 1759.[22] Also in 1678, that is, a year before the Privilege of 1679, the Sejm established the rights of the Jews in the Lithuanian in the Great Principality. This especially emphasized that they would not be judged by the city courts, but only through the voivode and the starostas [community leaders].[23]

As we see, these privileges from the royal government guaranteed the rights of the Jews of Vitebsk. The Jews could live where they wanted and engage in business and any professions. Things were different in Crown Poland, where the

[Page 10]

townspeople would force their Jewish fellow citizens to agree to a diminishment of the rights of the Jewish population in these areas. We can explain this by the great feudal backwardness of these White Russian areas and with the relatively greater weakness of the local citizenry. The Jewish population in White Russia was proportionately more educated than in Crown Poland in the cities in the business class and even more among the craftsmen.

The jurisdiction of the voivode over the Jews in Lithuania was, in contrast to Crown Poland, not organizationally divided into a so-called “Jewish court” of voivodes or subcontractors for whom there was a special “Jewish” judge (a Christian) or the vice-voivode together with the heads of the kehillah. In Lithuania, Jews were judged in the “castle courts,” each of which was headed by the voivode in the central district of each voivodeship and the starosta in their usual districts, whose administrative and juridicial competence applied to everyone who lived in the domain of the castle court, including Jews. This included even Jews who lived in other city districts that belonged to the magnates.[24]

The aforementioned return from White Russia and the relative weakness of the local citizenry made it possible for individual Jews legally to assume a privileged–and even a ruling–place in regard to other groups among the Christian population, who found themselves on a lower rung in the social hierarchy.[25] Profiting from the protection of highly placed officials, individuals–wealthy leaseholders of feudal estates and monopolies–felt like small rulers over the populations of villages and small towns who lived in the princely jurisdictions. Their social importance and prestige is shown by the fact that in official documents they are referred to as “Pan” and “Gospode” and not as “Unbeliever,” as was the case in Crown Poland.[26]

In the majority of documents related to economic relations, Jews appear as merchants and leaseholders. Often these professions are linked. So, for example, is the case of the wealthy Vitebsk

[Page 11]

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

[Page 12]

leaseholder Yakov Ilinitsh who leased for three years toll payments in Dinaburg, Polotzk, and Vitebsk, paying for the lease the high sum of over 50,000 groschen (23,000 Polish gulden), and also brought merchandise into Vitebsk and other cities.[27] A prominent merchant was Matisyahu ben Gershon (Gershonovitsh). On June 23, 1605, in the Vitebskk treasury he paid for 400 rabbit skins and 20 cow and horse skins two “shteyner” of honey (1 shteyn=32 pounds) and three “shteyner” of hops that he had brought in by ship from Velisz.[28] In the 20's of the seventeenth century, the public incomes of the Vitebsk voivodeship, or most of them, were leased by the Vitebsk Jew Yehuda ben Yakov (Yakubovitsh). In the Vitebsk treasury, Jewish writers affirmed the greatest Jewish leaseholders in Lithuania, such as Itzko Zelmanovitsh and Shmuel Zelmanovitsh Shereshevsky, in 1693 leased the toll payments in the whole Lithuanian principality.[29]

The Vitebsk kahal itself held business monopolies. In 1720 a three-year contract was confirmed for exclusive rights to the wine business in Vitebsk itself and in the surroundings for a distance of two miles from the Vilna chapter, which had had the wine monopoly in Vitebsk; and the kahal, behind which were reportedly the Jewish wine merchants, paid a sum of 9,000 gulden. In May of 1721, the chapter withdrew from the contract because of disagreements that broke out on both sides. It took over the business of alcoholic beverages and turned over 150 thalers to the kahal for leaving the contract. The voivode published a special notice about this business in the city records.[30]

As has already been noted, the Polish nobility combatted the Jewish leaseholders, especially the leaseholders for payments and other public incomes. In the year of the Polish-Lithuanian union, when the Lithuanian nobility gained equal rights with the Polish nobility, the united Sejm of 1569 decided to forbid Jews to lease payments and taxes.[31] But also this decision could not suppress the Jewish leaseholders, who were deeply entwined in the economic life and had a long tradition, just as the similar decision of the Petrikov Sejm in 1539 could not sideline the Jewish leaseholders in Crown Poland.

The voivode's sejms, where the middle, not wealthy

[Page 13]

levels were represented, constantly sought to repeat decisions to forbid Jews from access to certain incomes. So, for example, the Polotzk Sejm, which also represented the Vitebsk, ordered in 1718, 1744, and 1764 not only to forbid Jews from dealing in noble goods and public taxes but even from dealing in the lumber business. That meant wood, potash, and the like, indeed all the businesses in which they had an interest.[32] That this demand was repeated so often shows that it had little actual effect.

The legal frameworks for Jewish commerce in Vitebsk were quite broad. The Privilege of 1679, renewed in 1729 and 1759, show no limitations for Jewish merchants, as was the case in other Lithuanian and White Russian cities (Grodna, Vilna, Polotzk). On the contrary, the Privilege of 1679 emphasizes the usefulness that Jewish commerce brought to the city.

But in the practicalities of daily life, things appear otherwise. City hall and the guilds did not pay much attention to the royal privileges and took measures to limit the free commerce of Jewish merchants. In June of 1730, the Vitebsk city hall adopted a resolution that applied to Jewish merchants who came to Vitebsk to buy leather: no furrier should sell them their work without the agreement of city hall and the merchant guild,[33] as well as from the guild masters. Also shoemakers selling their products to Jewish merchant must have permission from the guild masters and must get a payment for the merchant guilds.[34] This decision strove at least to exercise control over Jewish commerce, if they could not forbid it altogether. The commerce of the Vitebsk Jewish merchants was largely in imports and exports with the Baltic harbors–Konigsberg and Riga. It first grew in the second half of the 18th century, but it began in the first decades of that century. A Vitebsk merchant, Yitzchak ben Yehuda-Leib Bloch, in 1772, presented to the Vitebsk treasury a list of 32 kinds of merchandise, among which were 3,387 arshin [a measure of length] of various materials, some woven with gold brocade and worth 20 rubles per arshin.[35] In that same year, the Acts note an interesting conflict between Vitebsk's Jewish merchants and the Konigsberg merchant Chaim ben Leib Friedlander that demonstrates the entwined business

[Page 14]

relationships between the Vitebsk and Konigsberg Jewish merchants involving credit, agents, and so on.[36] In addition, the sources tell us about business relations between Vitebsk's Christian merchants and Jews from Smolensk, Leznansk, and so on.[37]

The royal privileges also guaranteed the Jewish craftsmen the right to freely go on with their professions. The Privilege of 1679 stresses the principle that Jewish craftsmen do not have to belong to the Christian guilds, while in the Lithuanian Great Principality, the Privilege of Sigmunt III in 1629 had had the same effect. The economically backward White Russia, even more strongly than Crown Poland, had required this of Jewish craftsmen, even though their numbers were small. Certain privileges for Lithuanian kehillahs, for example, for Vilna and Kalvaria in 1713 and for Minsk Jews in 1722 freed the local Jewish craftsmen from paying the Christian guilds, which in Crown Poland was a fundamental, established, legal custom. Later, however, these payments were imposed in agreement with the city guilds.[38]

Vitebsk's Jews were also involved in the credit business, but it appear that they played a secondary role in their economic activities. The sources show that Jewish credit is barely depicted. We know of it indirectly from a statement that the Vitebsk kahal head in 1670 inscribed in the acts of the Brisk lower court at the time of the catastrophe of 1654 when they lost their documents concerning debts of the Vitebsk citizens along with all their possessions, which were taken by the Russian army.[39] Shimshon ben Avraham had large credit dealings in the second half of the 17th century. In May, 1654, he brought an action in the Vilna tribunal against the noble Anna Narushevitsh-Sapieho and the heirs of Nikolay Sviniarski, because of a contradiction to a judgment that awarded him the large sum of 56,000 “pence” and 5 Polish gulden, she refused an action against her goods in Bikov and Ostrov. Her aristocratic position did not pertain to the session of the tribunal, and the court sentenced her to “banishment.”[40] The king confirmed the sentence and excluded her from the Sapieho family, from the community of honest people and he forbade anyone to give her aid under penalty of severe punishment.[41]

[Page 15]

In the 18th century we already see a contrary phenomenon–Jews owing large sums to noblemen and clergy. An especially large debtor was the kahal. The greatest offense of the Jewish population in the 18th century was a result of its devastated economic situation, which was an outcome of the general economic decline, the anarchic conditions, and the Catholic reaction of that century.

A. Organization and Functions

The precepts that came in 1730 give us a detailed picture of the organization and functions of the Vitebsk kahal in the first half of the 18th century. They reflect the judicial status of various social groups in the kehillah as well as the means by which the kahal's oligarchy secured its power and leadership.

Electoral Rights: Election rights belonged only to those who had been inscribed in the kahal record book the year before (5489 [1729]) so that they had this right and paid taxes of at least four “k'tanos,” that is, a third of a Polish groschen. (A k'tanah or a p'rutah k'tanah in the 18th century was equivalent to a third of a groschen, and at that time the minimum tax was one p'rutah k'tanah, and the maximum was 20 p'rutos k'tanos.) A person who had the title of “chaver” (member)–8 k'tanim. The head of the kahal or the kahal leaders had the right to cede their vote to someone else, as did one who “bore the yoke of the kahal.” He, and this was not the custom, could transfer his voting right only to one who had a voting right. He who was the head of the kehillah for three years and a kahal leader for four years had voting rights even if he had not paid his tax; one who had been the head of the kahal even for a single year, if he paid only 6 k'tanim, that is, two groschen, had voting rights, even if he was a member. (The minimum tax for a member was 8 k'tanim.). Those who had no residency right, had no voting rights for three years, since they were inscribed in the record book in the list of taxpayers. He could be elected to a place in the kehillah after 4 years. A property owner could not transfer his vote over the course of three years.

Craftsmen had no voting rights after the date of the precepts,

[Page 16]

but the craftsman who had had this right earlier retained the right by tradition. Someone who had had no voting right, neither the head nor tradition could grant it. A workman could not be chosen for a higher position such as manager of a charity fund.

A property owner could have no more than two votes. No one else could use his votes if it was not specified in the name of the kehillah or by the property owner himself.

Election of kahal officials: The bor'rim (electoral arbitrators) select not more than 9 manhigim (leaders), consisting of 6 roshim (heads) and 3 tovim (notables), so that if one manhig may be unfit, there would still be two others. Aside from this, people could choose, as we see from the voting records of 1711, 1712, and 1713, the following kehillah offices, some of which are indicated thus: for the general good (17 men); 2 trustees (in 1713–3); 3 auditors (in 1713–4); 4 charity fund trustees; 5 judges of the first level (in 1713–4); 4 judges of the second level (in 1712 and 1713 there were 3 judges of the third level); 4 trustees for the synagogue building; 4 trustees for the organization of visiting the ill; 4 trustees for the bridal fund; 4 trustees for the Talmud Torah; and 4 (in 1713–3) trustees for Eretz Yisroel. Together with the above mentioned 9 manhigim, the number of elected officers came to between 44 and 49, a remarkable staff of officials.

There were two committees–a committee of 17 officials and a larger committee of 27. It is difficult to establish who belonged to the committee of 17, probably the most important being: the manhigim, the trustees, the regulators. Belonging to the committee of 27 were: 6 heads, 3 tovim, 6 trustees of the charity fund, 2 property owners who paid high taxes, 2 judges, and 2 auditors. As for the other 6, they were taken from among the manihigim of the state, that is, from the representatives of the Vitebsk kahal in the “Va'ad medinas Rusia” or from the Vitebsk judges in the “Va'ad ha-medinah.” The functions of the committee of 27 were in reference to matters concerning the rabbis, the chazans, and the shochets, leaseholders, elections of trustees and leaders of Vitebsk to the Va'ad ha-medinah, as well as charges against the dimensions of the head taxes and the level (of the property taxes) by the assessors

The precepts of 1730 present the restrictions to election to the highest kehillah offices:

For example, an elector who until the day of the elections had not

[Page 17]

held an office could not stand as a candidate for a higher office than trustee of the charity fund.

|

|

Anyone who belonged for three years to the committee of 27, even with interruptions, could be a candidate for the position of manhig, that is, one of the leaders of the kahal. No one who had been in a lower position could nominate himself for the position of head of the kahal. That had to be done by others. Only one who had been among the tovim of the kahal for three years could nominate himself for head of the kahal. In order to be nominated by others for a leadership position, it was enough to have had a position in the kahal for one year. In the kehillahs that belonged to the Vitebsk kahal, one could be chosen as head even after one year in the leadership. Of leaseholders of taxes and kahal income, as long as their contract was valid, only three could be chosen.[42] According to a ruling of the beis-din, one more could be chosen, that is 4 altogether, but they could not stay in the same position for more than two years. The tax assessors would be chosen in a special election which was open to the leaders of the kehillah and others specially chosen who were prominent.[43]

[Page 18]

These stipulations in the election rules served, on the one hand, not to allow, or, in any case, to make it more difficult, for new people to get an office. And on the other hand, they made it possible for the same kahal oligarchy to maintain their power, just shifting around offices from time to time.

The electors were strict about adhering to the regulations. Violating them could result in losing the right to hold office for six years and the right to vote for 10 years.[44] Nevertheless, the rules were occasionally violated because people did not pay attention to them. In 1721, the record book notes, The elections did not agree with the rules. So a committee of 6 important men was chosen, together with the rabbi. They decided that in order to still the controversy, the election would be confirmed. However, if it would not be possible to regulate the election during the year with new rules, the electors were required to hold new elections according to the old rules. (The election regulations of 1720 were not in effect.). On the other hand, if the election was not valid, everyone had the right to deny the illegal vote report and the electors would lose their right of appointment for a year.[45]

The kahal also supported paid positions–a rabbi, judges, a chazan, a preacher, a shochet, a trustee, a kehillah scribe [possibly the keeper of the kehillah record book], and others. The kahal would make special arrangements for these positions concerning their wages and duties. For example, we can look at the arrangements for the head of the Vitebsk beis-din, R' Sheptl of Lublin, who in 1726 was elected for the following three years. His wages were 200 gulden per year, but he also had other income: he was paid 100 gulden by the innkeepers [?], 50 from the meat tax, and 100 gulden by city residents and those in surrounding areas. In addition, he received 7 thaler, including 2 red (golden thalers) from various sources (from both taxes, from surrounding minyans, from the “appraisers,” electors, from giving sermons on Shabbos Chanukah and Shabbos Ha-gadol). The kahal also made arrangements with the sexton and shochet: the sexton received a gold piece each week. If he had no other income, he received another 75 gulden from the surrounding residents each year. He was not exempt from taxes, aside from the property tax. He

[Page 19]

had to carry out all the orders of the kahal, apply pressure to the recalcitrant, conduct excommunications, admonitions, and penances (for the sinful). The shochet's agreement called for 25 gulden (probably yearly). In addition, he received 25 gulden from nearby residents (for showing them where they could stay when they came to town for the High Holidays). He kept the property lists of the taxpayers, for which he received a small monthly payment. The sexton and the shochet also had to swear in the appraisers and their supervisors.

The kahal could interfere with the court procedure of the beis-din, as it appears from a ruling from the second of Sivan 5485 (1725) that forbade the beis-din from hearing witnesses if the two sides were not coming to trial. The sexton had to warn each side twice, and if either did not come to the beis-din, then witnesses could be heard. Also, a trial could not be held if the kahal sexton was not there; and, on the other hand, the sexton was forbidden to be during the trials of the beis-din without the permission of the head of the community council and two of the leaders.

The kahal also had its shuls. The oldest shul in Vitebsk was built in the first period of Jewish settlement there, that is at the latest in the second half of the sixteenth century. In the rescript of the Vitebsk voivode Sagnushko of 1627, which allowed the Vitebsk kehillah to build a shul in the place that belonged to the castle or in the city itself, he refers to the privileges of the earlier voivodes. In them it is affirmed that the Vitebsk Jews had already had their shuls.[46] At around the same time, it appears that the shul did not exist. The building of a new shul was undertaken in 1630. In that year, a representative of the Vitebsk kahal, the leaseholder or accountant Yuda ben Yakov laid before the city leaders the aforementioned paper from the voivode of 1627 as well as a letter to the assistant voivode in which the voivode ordered no interference with the leaseholder inserting the shul building within a certain distance of the place where the shul was supposed to stand, even though a path was there.[47] At the time of the war in 1654, the shul was not destroyed. In a list of the survivors in Vitbesk, Voivode V.P. Sheremyetev in 1654 numbers, among the Catholic and Ukrainian Catholic churches, the Jewish shul.[48] At that time, the Vitebsk Bernardine Cloister claimed the place where the shul stood, but the Vilna

[Page 20]

bishop Bshastovky and Vitebsk voivode Patshei ruled in favor of the Vitebsk kehillah.[49] The shul stood until 1711 or 1712,[50] until it burned. (The fire destroyed the Jewish quarter.). Building a new shul required a battle from the kehillah, traces of which are found in the sources.

In the kahal record book, under the date of 19 Kislev 5472 (1711) it is written that the “lords and nobles did not allow the rebuilding of the shul. We had to give many bribes until, with God's help, we received permission to build the shul.” In the meantime, the city rulers inflamed the masses, and during a pogrom that broke out in the city in 1712 they seized the area and built a church there (or at least put up a cross). Jews complained to the voivode. In his letter of June 22, 1712, to the Vitebsk assistant voivode he ordered that the cross should immediately be removed from the shul location, that there should be no further persecutions of Jews, and they should wait until his return from Vilna to rebuild the shul. However, the priest Bulhak, who appears to have instigated this holy war, did not agree to remove the cross, and he ordered that the cross should be taken out at night and anchored in cement.[51] Whether the voivode's orders were carried out is not known. When the whole matter was laid before the crown tribunal, the latter issued a verdict on September 15, 1712, which, aside from compensation for the material possessions and bodily injuries in the amount of 13,500 gulden, assigned the spot to the Jewish kehillah.[52]

In 1726, the record book notes a “synagogue across the river,” that is, in the district of Zarutshaya. Whether this was the same one over which there was such bitter conflict or another one is difficult to determine.

Also, the Vitibesk kahal had no rest over the old cemetery either. In the seventeenth century it was at the place that had belonged to the Orthodox Metropolitan Cyprian Szuchovsky, but the Christians who lived in this clerical jurisdiction, took this spot that bordered on their parcels. On May 8, 1677, the Metropolitan's steward gave ownership rights of the cemetery to the kehillah.

[Page 21]

This decision was confirmed by the Metropolitan himself on April 18, 1678. Thereby were the Jews (in the documents they are called “Herr Jews”) guaranteed eternal and peaceful ownership of that place, and their neighbors were warned that if they were to abuse the Jews attack them or stir up the mob, they would be punished with a fine of 130 times sixty Lithuanian groschen. On July 18, 1676, the Vitebsk counselor Ber Hirshovitz presented this document to be recorded in the Vitebsk Surrogacy Books.[53]

Charitable matters were conducted by the trustees of the Great Charity. According to a rule in the record book of 1724, they had income from the sale of honors in the shul and the beis-medresh. It is interesting that for buying an honor on Shabbos and holidays, they had to have a sanctuary. Without a sanctuary, the sexton could not sell the aliyos. Also, vows of “secret gifts” belonged to the charity fund, and therefore the trustees had to devote some of their income to wood for heat and light in the shul. On one Shabbos a month, 13 specially chosen people, called mispal'lim [worshipers] were called to the reading of the Torah. This was a lifelong privilege for a small group from the “eastern wall.” The above mentioned rule of 1724 notes also that there should not be a perpetual chazan but that the worshipers should take turns at the reader's stand.[54]

According to a rule of 1726, the monthly leader had the right to give charity to a traveling guest of up to three gulden. To give more required the agreement of two other leaders. About the greater number of wandering guests [that is, poorer people], witnesses say that the same rule forbids giving to the wandering poor because the whole income from the communal tax would be given away.[55] Also the trustees of other fellowships, like the chevra Kadisha [burial society] of the shul in Zarutshaya and the women's fellowship, were forbidden by rule to give even a p'rutah of charity without permission from the monthly leader. A violation would invoke a fine and removal from office.

The accounts of expenditures that were made by the head or the monthly leader were presented at the beginning of the next month by the auditors. On one accounting from 4 Tamuz 5473 (1713) is a note: Yegomoshtsh Pan. From this we can see that the voivode or his representative controlled the kehillah's budget.

[Page 22]

The kahal demanded obedience and assumed the right to interfere in the private lives of its members. Along with the rules for elections in 1730, the kahal record book describes a rule that if anyone is summoned by name to the kahal or to the beis-din and does not come and the sexton summons him a second time with a note from the monthly leader and he still does not come, the disobedient one should be excommunicated. A second rule says that if someone goes in a bad direction (in the record book: in an impermissible way), he should immediately be persecuted with every kind of punishment (including excommunication) until he comes to the kahal and accepts the judgment that has been imposed on him and no monthly leader can remove the excommunication from him, under threat of his own excommunication.[56]

In order to combat frivolousness at celebrations, special rules limited the number of invited guests, the number of meals, etc. According to a rule of 1725, it is permitted to invite not more than two minyanim [20 people], aside from close relatives, in-laws, the rabbi, the shochet, and 5 who do not pay taxes. Each guest can be invited for one meal, and guests for each of the three meals will be determined by chance. It is forbidden to honor the guest with “alcoholic toasts.” It is forbidden to make a special meal for women. For a bris it is forbidden to invite more than three minyanim [30 people], aside from the mohels, the sandek, the rabbi, the chazan, the shochet, near relatives, 5 who are tax-exempt, as well as the guests. Someone who does not pay taxes cannot invite more than a single minyan to a meal, aside from near relatives and in-laws. The sexton and the officers cannot be invited to a celebration until the “guardians of the rules” sign off on the number of guests. We can see how important these rules were considered when we see that they were signed by the head and manhig of the state, Shmuel Segal, the head and manhig of the kahal, Reuven Katz, and the monthly leader.[57]

The kahal was responsible for governmental taxes of its members. These taxes were: Poglovna (the head tax, the per-person tax), introduced in 1549. Until 1579 it amounted to 1 gulden for each person in a family. In that year, the government changed to another system: they determined a general sum for the head tax that all Jews were required to pay, and the kehillah

[Page 23]

was responsible for the total. For the Jews in Crown Poland first amounted to 10,000 gulden and for the Jews in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania–3,000 gulden. Later on, the sum was increased several times and in 1717 amounted to 220,000 in Crown Poland and 60,000 in Lithuania; 2) “Dim” or “Podima,” a tax on houses and on places, with the exception of houses that belonged to the not-wealthy. For this tax, too, in 1652 they instituted the same system as for the head tax in 1579; 3) “Hiberna,” taxes to maintain the army. This tax was paid only by merchants, shopkeepers, and craftsmen[58]; 4) a tax on Christian servants, which in 1714 amounted to 4 tinfin (a little more than 54 kopeks) per servant[59]; 5) “Shelongovy,” a tax on the sale of liquor and so on.

Aside from these normal taxes, a number of extraordinary taxes were imposed on the Jewish kehillah, occasional payments in money or goods, annual gifts for secular or religious dignitaries, and so on. So, for example, the Vitebsk kehillah, before and during the siege of the city by the Muscovite soldiers in 1654, built fortifications and defensive bastions, supported the army with food and lodging, supplied gunpowder and horses, voluntarily doubled the head tax[60], and so on.

These extraordinary taxes that the Vitebsk Jews paid during the war also began to be required after the war, when people returned from Russian captivity. The ruined and sorely diminished Jewish kehillah (many Jews having been killed during the war and in captivity), could not bear such heavy taxes and asked for appropriate adjustments. Then the Lithuanian hetman and Vilna voivode, Kazimir Jan Sapieho, issued a strong statement, dated from Grodna on March 27, 1688, to all military commanders not to force the Vitebsk Jews to house soldiers and not to requisition their homes for this purpose, not to take “voluntary” gifts, and also not to take their sons for military duty. He referred to several Privileges that freed the Jews from the obligation to pay the “Hiberna” taxes.[61] This provision, it seems, was later forgotten. In 1691 and 1717, the Vitebsk voivodes had to make special notice of it.[62]

[Page 24]

According to the constitution of the Petrikov Sejm in 1539, Jews who lived on the land of a noble were exempted from paying government taxes. (An exception was made in 1552 for the head tax.). This principle was also ordered for Lithuania, and the Vitebsk voivodes, who themselves owned large “jurisdictions,” paid attention so that no one violated this rule.[63]

Exempt in principle from taxes for the kingdom and for the city, Jews in the noble properties and city jurisdictions paid the owners for leasing the inns and for selling alcohol, which was a monopoly of the nobles. But around the halfway mark of the eighteenth century, the Jews in the nobles' jurisdictions and in other “extraterritorial” city areas were brought to parity in terms of taxes with all the other Jews of the city (by decree of the Vitebsk voivode Josef Osnowski on July 8, 1750).[64]

As for the head tax, the highest organs of the Jewish organization–the Council of the Four Lands in Crown Poland and the Council of the State of Lithuania in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania–leased the tax from the royal treasury. The Councils would divide the taxes between the Va'adei Ha-Galil in Crown Poland and the leading kehillahs in Lithuania,, and they would assign sums to the various kehillahs in their areas. Then, within the kehillahs, the head tax and the other taxes were imposed on each individual taxpayer.

The kahal had a large expenses from maintaining the kehillah offices, the kehillah institutions, from giving bribes and gifts to the royal, city, and religious officials, from charity, from contributing part of its budget to the Council of the State of Russia, and so on. All of this required large and secure incomes. From direct income and property taxes, they could not amass enough, so the kahal, in its tax politics, cast a broad net for indirect taxes and even itself monopolized certain sources of income. Over all, the kahal was the highest regulator of economic life in the kehillah. So, for example, we know from the record book of 1723 that the kahal monopolized for itself the right to appoint those who would get leases for inns. This, naturally, aroused disagreements from the former innkeepers. In order to consider their complaints, a commission of two people from the kahal and two innkeepers was appointed.

[Page 25]

Everyone who had a complaint against the kahal was supposed to go to this commission. This decision was announced in shul.[65]

The most important source of income for the kahal became the community tax. In the first quarter of the 18th century, this tax applied to two important items: meat (slaughtered in the kosher manner) and the sale of alcohol. These taxes were mostly leased by people from the kahal or by others in a transparent fashion. In 1725, the meat tax was leased by the head of the state, Duvid Tzvi ben Bezalel and the head and manhig of the Vitebsk kahal, Mordechai ben Avraham, for the sum of 6,000 gulden. It is interesting for us to know the important details of the agreement that the kahal made with them: 1) from the slaughter of a kosher cow, the tax collector would get the hide and 10 Polish groschen. If someone slaughtered for his own use, the tax collector would get only the hide. 2) For a cow that became unkosher, the butcher had to give for a full-size one 1 gulden and for a thin one 14 Polish groschen. 3) For a wedding, two cows were exempt from tax payments, and for a bris, one was exempt. This means that if one does the slaughtering himself. However, if one buys it from a butcher and one buys less than two cows worth, the tax collector gets a portion of the hide according to the value of the meat that was bought. 4) In order that the tax collector can have control over the slaughtering, the kahal cannot use a shochet without the collector's knowledge. Also to be penalized by excommunication is someone who brings in meat from the outside and violates the rules of this agreement. 5) The kahal also secures the leaseholders against claims and presumptions from the kahal's debtors.[66]

The amount of the “innkeeper tax” in 1706 amounted to three Lithuanian groschen per pot of liquor, but in 1711 it was already 8. But those who used holiday pots, that is, pots reserved for Pesach, had to pay only half.[67] In addition, the kahal took payments from merchants and moneylenders (the merchant tax): from merchants who conducted business with Riga–6% of business capital, from wagoneers–1.5 groschen per gulden (5%), and from moneylenders–3 groschen for each gulden (10%).

The kahal paid attention that no outsiders should interfere with its tax operations. In 1711, a rule was made that imposed a fine and excommunication on anyone who would interfere in such matters without the kahal's consent. A partnership

[Page 26]

of several individuals who wanted to take over a kahal business (no details are given in this rule) was declared void.[68]

The kahal upheld the interests of local Jews over those of outsiders who had no residence permits and who with their businesses and leases created competition for the locals. At a meeting in 1711 at which people complained about the arrival of people from abroad (probably in connection with confusion from the Russian-Swedish War), which caused the kahal a great deal of trouble,[69] a special committee of three was chosen. They promulgated the following rules. On the one hand, they made it difficult for foreign Jews to settle in Vitebsk. On the other hand, they saw that the foreign Jews could be a source of income. Their rules were:

[Page 27]

it also had a share in the debts of the Council of the State (both of Lithuania and of Russia). For not paying on time a debt of 9,420 gulden, the property owner Hoshtshilowska in 1700 sentenced nine manhigim to death. Among those sentenced was a representative of the Vitebsk kehillah.[71]

It sometimes happened that the kehillah had no other option but to give an insistent debtor money from the taxes. So, for example, the kahal guaranteed the debt that had been incurred by Vitebsk's Mikolay Re'it with the income from the taxes that he received in lease. Or, on the contrary, the kahal would make an agreement with the leaseholders of the tax that they should pay, in addition to the agreed upon sum, also the debts for which he was responsible as a private person.

When the kahal was sinking in debts. There were also reliable people for whom it was difficult to get a loan, so they had to meet strict conditions. When the Vitebsk kahal in 1764 had to borrow, for kahal purposes, 1,100 gulden from the Smolensk “kroitshi” (such was the honorific in that Polish place) Ivan and his wife Benedicta Bazeiki for three months, the debt was personally guaranteed with all their possessions by the head of the kahal and by all of Vitebsk's Jews, with their wives and children. They also pawned the shul and the whole income from the taxes; that is, in case of non-payment of the debt, everyone could be arrested, the shul could be closed, and their property could be seized, as well as the taxes. Despite these harsh terms, the kahal could not pay off the debt, and the lender had no choice but to extend the debt for another six weeks, so that the Vitebsk judge Theophile Mogutci became the guarantor.[72] Did the kahal meet the new terms of the debt? Probably.

The kahal had to worry about whether the payers of the communal tax would cheat and pay according to the value of their possessions or according to their assessment. To this end there was the institution of the assessors. As we said, the assessors were chosen in a special election. They took a vow to do their jobs with justice and objectivity.[73] The assessors kept a record book of the taxpayers in which they would record, according to their estimate, the provisional sum of the tax. The taxpayer had the right to question the correctness of that estimate. The assessor could take this evidence and reduce the sum. But if there was no trust between them, he could

[Page 28]

force the taxpayer to take an oath.[74] If the taxpayer did not want to swear or had not brought any significant evidence against the evaluated sum, then the sum that the assessor had entered into the record book was confirmed. But if someone gave false information under oath about possessions, the strongest measures would be taken against this taxpayer. A rule in the kahal record book from 19 Sivan 5495 (1735) states that if someone paid no taxes, he could not marry, no one could sell him kosher meat, his sons could not be circumcised, no one could come within four cubits of him, and after his death he would receive the burial of a donkey. In fact, he would be an excommunicant. A rule from 1722 said that from the recalcitrant, taxes could be seized by force.

What the assessors could do according to their own decision about who should swear and who should not naturally aroused bitter feelings among those who had to swear and they protested this decision and did not want to submit. So in 1722 the rule makers decided that everyone must swear an oath about the state of his property and money, jewelry, clothes, houses, goods, and debts. The assessors were not allowed to establish the preliminary tax list according to the amounts of previous years, but they had to make their estimates according to the property declaration for that year.[75] This rule, however, did not eliminate the difficulties of the assessment system. In 1727, we again hear of complaints from the householders, who were unhappy with the level of the taxes that the assessors had established. A large gathering of the kahal decided to force the assessors under threat of excommunication to declare that they had corrected the sums for the householders who understood their error. Given that some of the householders sought protection from the Council of the State and wanted a letter of recommendations to the kahal, the gathering decided that they must present this letter to the assessors, whose decision would be final.[76]

In 1735, the procedure, the procedure for determining the amount was finalized, namely the each homeowner was responsible for giving to the assessors a list of his possessions, which the assessors would consider and tell him the level of his taxes, so that the taxpayer would know before his oath how much he was assessed. After the oath, his property declaration would be written in

[Page 29]

the record book and the sexton would announce in the shul that every person who knew the situation of this or that householder should, under threat of excommunication, examine their property report in the record book and inform the kahal manhigim. If it appeared that the property list was inaccurate and the person had violated his oath, the kahal could use any means to persecute him. The rule of 1735 set aside the control of taxes from the public control of all members that had probably caused more oversight over the possessions than earlier, although on the other hand it created the possibility of using this right for personal accounts among the kahal members themselves.[77]

At that time the Vitebsk kahal counted many Jewish residents in the Vitebsk, Velizh, and Lepel districts, such as Ostrowno, Velizh, Oyswiat, and others. According to the census of 1765, the Jewish population in Vitebsk itself numbered 667, and in the kahal surroundings–1,692 (not including infants). The Jewish inhabitants of these settlements were subject to the Vitebsk kahal in matters of taxes, the beis-din, and so on. Consequently, there were often conflicts between Vitebsk and its surroundings that were brought to sessions of the Council of Russia. The Council of the State responded to attempts to stop paying taxes in the case of the Vitebsk kahal and to try to emancipate themselves from the Vitebsk kahal on the part of the smaller kehillahs with dire threats and repressions.

1. In the Time of Catherine II (1772-1796)

In 1772, it was decided by Russia, Prussia, and Austria to take territory from Poland (the First Partition). According to their agreement, Russia received part of White Russia with the cities of Mohilov, Polotzk, and Vitebsk. At the Second Partition in 1793, Russia received the remaining White Russian territories.

The Jewish population in Vitebsk in 1772 numbered officially 1,227 souls, and in the cities and towns of the Vitebsk district 797 souls (64.8%), so that the number of Jews in Vitebsk had almost doubled in comparison with the 1765

[Page 30]

(667 to 1,227). In fact the number of Jews in the district had diminished by more than half (from 1692 to 797) does not work, because of its unlikelihood–a growth during seven years of almost 100%--one cannot trust them. They undoubtedly show, however, a tendency to leave the small settlements because of the troubled times and to settle in the larger kehillahs, where the settlers hoped to find more security.

White Russia was incorporated into the Russian Empire during the years of the short-lived liberal era in the politics of Catherine II. This fact also finds expression, although without consequences, in the politics regarding the newly incorporated nearly ten thousand White Russian Jews. The district of 1776 maintained the old Polish form as Jews as a tax-paying and collectively responsible group, so that people had to maintain the old Polish kehillah organization with autonomic rights (in district and gubernia kehillas) for internal Jewish matters. In mixed affairs–that is, between Jews and Christians–the Jews came under the jurisdiction of the city courts. Two years later, the Ukase of 1778 ordered the incorporation of the Jewish and White Russian populations (in the villages as well) into the two city classes (merchants and petty bourgeoisie). On the same basis, 5 years later Jews were given active and passive voting rights for the organs of city self-government (Ukase of 1783). This ukase made a large transformation in the previous rights of the Jews, and the people of the city, who for hundreds of years had regarded Jews as being on a lower level, sabotaged the order to allow Jews to vote in communal elections. We can see this clearly in the example of Vitebsk.

In Vitebsk there were elections for the mayor and three judges in 1786 without the participation of Jews, against which the kahal complained to the governor-general. During the months from January to March the governor-general four times ordered the Vitebsk city hall to conduct new elections with the participation of the Jews, but his orders were ineffectual. In May, the Christian community (probably the merchants' union) informed city hall that they would not have new elections, and city hall immediately accepted that information. In the meantime, the Vitebsk kahal sent the empress a complaint against the illegal actions

[Page 31]

of the city hall, and in July, the governor-general, Pyotr Passek, strongly ordered city hall to call for new elections. Otherwise they would be held responsible in court. (Earlier they had been disciplined for sabotaging the elections with a fine of 100 rubles.). This worked. On July 27, there was a general meeting of Christians and Jews where the city hall proposed that of the 100 elections people, the Christians should choose 75 and the Jews 25. (The Jewish merchants and petty bourgeoisie at that time, according to the official census of 1784, comprised 26.2 percent of the population, 1759 Jews and 6591 Christians.). But the head of the Vitebsk kahal, Duvid ben Shloyme, did not agree to thus number of Jewish election men and the Jews left.

At the beginning of August, the governor of Polotzk personally came to Vitebsk and the elections finally occurred. The merchants from the three guilds (16 Christians and 12 Jews), chose a mayor and 2 judges. Among the last chosen was the Jew Moyshe ben Shmuel. The governor said in his report, that “the to-do about the election occurred…because the Christian community was very obstinate regarding the participation of Jews in the election…It was led by the city hall, with Golova at its head.”[78] In 1789 we already encounter in the reports two Jewish councilmen: Litman and the above-mentioned Duvid ben Shloyme,[79] and in 1803, the councilman Shmuel Yankelovitch.[80]

The district, in order to calculate all the Jews in the two city ranks brought to economic ruin many village and small-town Jews, who were forced to leave their homes and their village jobs. The percent of village Jews in the Vitebsk district, for example, in 1772 was in 907 villages, more than a third (39.4%) of the whole Jewish population.[81] The Polotzk governor zealously pursued the policy and in 1782 ordered that Jews must immediately leave the villages and settle in the cities. Thereby he strongly told the nobles not to help them. The economic existence of thousands of village families was undercut. It appears that passionate clerks later began to drive Jews out of the small towns that belonged to nobles, and the aforementioned Passek issued a new order in 1796 that declared that the turmoil between the small-town Jews and their lords (they feared the loss of their good-milking cow)

[Page 32]

was groundless, because the law referred actually to the villages and not the small towns. The Jews who had been driven out had to settle only in the district or gubernia cities or places where they had already been enrolled in the course of a year.

In the meantime, the law was extended to cover the village jobs of city Jews, like breweries or liquor purchases. In September of 1795, that same Passek ordered that everyone who had not paid taxes, and Jews, without exception, could not deal with liquor or with breweries, with the usual motive that according to the law Jews could only deal in commerce because their dealings with alcohol led the peasantry into drunkenness.[82]

These were the first “profits” of the White Russian Jews from the new czarist government and a threatening omen for what would come later.

The regime itself had, as it appears, recognized that it had gone too far, and to a request from a deputation from the White Russian kehillahs to the czarina in 1784 that complained about the injustices that resulted from the law and from its arbitrariness, the senate in 1786 ordered the abrogation of Passek's order of 1782 that took away from the village Jews the right to brew and to have inns. At the same time, it stopped the expulsion from the villages to the cities, where crowding and need had both increased. The senate's decision also narrowed the scope of Jewish kehillah autonomy: the city courts, which were constituted proportionally of Christians and Jews, were thereafter wholly in charge of civil and criminal trials between Jews, while the rabbis in the district and the gubernia kehillahs had jurisdiction only over religious matters. The kahal also had to bear responsibility for taxes.

Although the ukase established the principle that Jews were equal members of the two classes in the city, this was later totally forgotten, and in 1794 the Jews were burdened with doubled taxes compared to Christian citizens, with the generous “concession” that anyone who would not accept this burden must leave the country after paying a fine–doubled taxes for three years. In addition, White Russian Jews were forbidden to settle in the interior Russian gubernias where they had to occupancy rights, so that they could stay there only

[Page 33]

temporarily. Thus did White Russia become the first “Pale of Settlement” under the czarist scepter.

The relatively liberal course of the first half of Alexander I's reign changed little in the situation and relations to Jews. These were changed by the agenda of the Jew-hating report of the czarist “expert on Jews” Derzhavin, whose knowledge of Jews was shaped in Vitebsk by the local Christian citizenry, by the teachers at the local Jesuit college, and even by the Vitebsk Cossacks. (He wrote his report in Vitebsk in 1800.) At that time was organized the “Committee to Organize Jews” and the Statute of 1804 was issued. Article 34 of the Statute ordered that as of January 1, 1808, no Jew in the villages and settlements could hold a lease, have a tavern, an inn, sell liquor, nor even live there. These restrictions were especially oppressive in Vitebsk Gubernia.[83] The ukase of December, 1808, called for the expulsion of Jews from the villages at an indeterminate time.

The Statute of 1804, in agreement with the Enlightenment tendencies, promoted the assimilation goals of the government by giving the Jewish population free access to elementary, middle, and high schools, as well as the right to establish their own schools, where one of three languages–Russian, Polish, or German–would be taught. In practice, however, this had a meager effect. For the cultural situation of the Jewish masses in Russia it was premature. We can see this in the example of Vitebsk.

To a question by the school examiner Pyotr Tzeis to the Vitebsk kahal–“What efforts had been made to establish a beginners school for the children of their people?–the kahal responded on August 2, 1808, that the kehillah could assume no financial burden for establishing a school. Also, there was a lack of Jewish teachers, because they could teach only Jewish children who understood no Russian. The kahal took upon itself to remind Jewish parents of school-age children that they should “accustom” their children to one of those languages so that later, when such a school would open, it would make instruction easier. This response was signed by three members of the Vitebsk kahal: Abele Shalit, Meyerson, and Nachum Bogorad. Similar

[Page 34]

evasive responses were sent by almost all 16 White Russian kehilahs, to which the examiner responded with other questions.[84] When the governor of Vitebsk around 1820 decided to carry out an examination of the status of Jewish schools, the clerical minister for education and faith, Count Golitzin, did not go along, because his ministry was preparing a new order about the matter and because people could not open special Jewish schools because of the poverty of the kehilas, the lack of Jewish teachers, and so on. The senate, in its decision of August 14, 1821, confirmed the position of the minister. For Golitizin, Jewish schools were a poor way to accomplish his goals of assimilation and apostasy.[85]

In the organization and function of the kahal, the Statute of 1804, which imposed on it responsibility for Jewish taxes, changed little. And although the Jews were placed under control of the city hall, the police, and the common courts, they still had the right to elect for three years the rabbis and the kahal leaders who had to pay attention to religious matters and arbitrate disagreements about religion. (The rabbis were strongly against the use of excommunication.). But actually the beis-din took up civil matters between Jews. The elections for heads of the kahal and rabbis always had to be confirmed by the gubernia government. The regime recognized the kahal as a legitimate representation of the kehillah in matters other than religion and taxes. Three times–in 1803, 1807, and 1818–it called representatives of the Jewish kehiilas to Petersburg in order to hear their thought about general Jewish matters.

The meeting of August, 1818, in Vilna, in which 18 kehilah representatives participated in order to elect deputies to Petersburg, chose, among others, the Vitebsk representative Beinush br”tz Lapkovsky, and as his deputy Mordechai Lepler.[86] The Petersburg deputation sat in the capital for a number of years doing nothing and over time was transformed into a group of intercessors led by Zundel Zonenberg from Grodna. It was dissolved in 1825 when the reaction of the second period of Alexander's reign had become entrenched.

Earlier we spoke of the expulsion of 1808, and in April of 1823 an order was issued to the governors of

[Page 35]

Vitebsk and Mohilev requiring that 1) in all village settlements of both gubernias, all Jews were forbidden to hold leases, inns, taverns, or to live there; all lease contracts should be nullified by January 1, 1824; 2) the Jews should be expelled from the villages by January 1, 1825; 3) Jewish peddlers are forbidden to enter the villages with merchandise. The Vitebsk governor was motivated to make his order of April 11, 1823 by the czarist ukase at the request of the White Russian nobles and the opinion of Senator Baranov that the chief cause of the bad conditions of the White Russian peasants was the village Jews with their trade in alcohol.

The administration hastened and already by January 1, 1825 had driven 20,000 Jews out of both gubernias. Of those, 7,651 had settled in the cities of Vitebsk gubernia, many of them in Vitebsk itself.[87] How much the Jewish population in the villages had declined after the first phase of expulsions, beginning in 1782 can be seen in the fact that in the area of the Vitebsk kehillah, there were only 210 Jewish families in 1811, constituting 17.1% of all families. (In 1772, there were 797 Jewish families, 64.8% of all families.) The expulsions of 1823=1824 led to a greater emptying from the village settlements of their Jewish residents. At the expense of the villages, it appears that that the Jewish population in Vitebsk grew–from 1,227 people in 1772 to about 5,940,[88] that is, almost fivefold.

The census of 1811 reports on the professional structure of the Jewish population in Vitebsk at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In that year there were only 9 families that belonged to the merchant class, and 1,224 families to the petty bourgeoisie (store owners, craftsmen, and so on). Of handworker families there were 405 (33.1%), of whom 126 were tailors (31%), 53 were butchers (13%), 35 were goldsmiths and coppersmiths (8.6%), 32 were carpenters and masons (7.9%), 27 were painters (6.6%), 24 were distillers (5.9%), 24 were tanners, and 23 were shoemakers (5.6%). All together these professions accounted for 84.5% of the craftsmen. The census also reports: 19 button makers, 13 hairdressers, 8 watchmakers, 6 musicians, 5 cotton workers, 4 parchment makers, 2 candlemakers, 2 salt dealers, 1 engraver, and 1 weaver. In the villages, 198 families had leases of inns and another 12 of labor. That means 5.7% of all village families, 6 times less than among the city Jews.

[Page 36]

Despite the Jew-hating politics of the Russian regime, during the Franco-Russian War of 1812, the Jewish population generally took a pro-Russian position and in many cases showed active patriotism by spying on the enemy, giving food to the soldiers, taxing itself to support the war, etc. There was even a case when, in a shtetl near Vitebsk, a Jew stopped a French courier who had a dispatch from Paris for Napoleon and brought him to the Russian army headquarters near Vitebsk. The Jew did not return to his hometown, which had been taken by the French, and returned only with the victorious Russian army.[89] As Vitebsk's Jews participated in spying for the Russian army, Vitebsk's civil governor Lershen informed Field Marshal Barclay de Tolly.[90] In Leppel, the kehillah took under its protection wounded Russian soldiers whom the French had ejected from the hospital after taking the city, thereby saving their lives.[91] In the list of Vitebsk citizens who received medals for their contributions to the army in 1812 are these Vitebsk Jews: Simcha Kechin, Head of the Kahal Chaim Ettinger, Yankel Lichtenshteyn, Gershon (Grisha) Soskin, Avraham Berelson, and Yehoshua (Avsei) Mayevsky.[92]

The French got to Vitebsk on 19 Av 1812 and stayed in the city until 3 Kislev.[93] They bullied in the usual fashion. They requisitioned homes, furniture, and whatever they desired; they forced Jewish workers to work for the army. They plundered the city. According to a bill that the city duma presented to the governor in April of 1813, the general value of things belonging to the people at the time of the occupation amounted to 1,687,736 rubles, of which 1,003,780 belonged to the Jews that is 60%. (Fn.: according to other sources, it was 1,009,000 rubles [see page 68]). The human losses due to the outbreak of epidemics and victims of the enemy amounted to 2,415, of whom 1,204 were Jews (about 50%).[94]

Witnesses say, regarding the attitude of the French toward the Jews, that in August of 1812, after Napoleon left Vitebsk on his way to Smolensk, the commander of the city garrison, General Charpentier, named a civil governing committee, on which there was not a single representative

[Page 37]

from the Jewish population. The French did not trust the Jews.[95]

It took years until the Jewish communities in Lithuania and White Russian could recover from the destruction of 1812 and its consequences. But despite its great poverty, the population in Vitebsk markedly increased. In 1815, the Vitebsk kehillah had 5,426 souls, an increase over 4 years of 1,037 people, that is, 30.6%. In 1809, the distinguished, wealthy Naftali-Tzvi Hirsch Schlossberg left 40 thousand rubles in his will. Of these, 15,000 rubles were designated for various philanthropic causes, such as poorhouses, Talmud-Torahs, charitable funds, and others. At the end of 1812, the keeper of the record book complained that because of events, loans from the charitable fund had not been paid back and that the conditions of the will could not be carried out.

A year or two before the outbreak of the war, two large shuls were built in Vitebsk: one–the shul in the part of the city called Zahoria, which people began to build in 1806 and completed in 1810;[96] the second–a much bigger one, in Zarutshaya, was begun in 1809. Naftali-Tzvi-Hirsch Schlossberg left 18,000 rubles in his will for this purpose. And lest this sum be too small, people should take another 7,000 rubles from his properties. But the 25,000 rubles did not suffice to build the shul. The governor ruled that if the building was not completed, he would seize it for a church. So the Vitebsk beis-din in 1811 permitted the use of 7,000 rubles from the funds that Schlossberg had left for charity.[97]

Nicholas I's reign was the darkest period in the history of Russian Jews until the time of Hitler. In the history of the Vitebsk kehillah, it recorded the saddest pages. The worst edict–the cantonist-edict of 1827, was, in fact, an inquisition conducted against children that had no equal in Jewish history (aside from the Nazi killings of Jewish children over 100 years later). This edict, to be sure, did not skip over the Vitebsk kehilah.

After the first “recruitment” in 1828, the Jewish young men were put into three cantonist battalions

[Page 38]

that were located in cities with Jewish populations, Vitebsk among them. But because of fear that these children's contact with the Jewish population, however difficult that might be, would interfere with the conversionist plans of the “Russian intelligence,” it was quickly decided that the Jewish young men should be sent only to cities outside of the Pale of Settlement. Apostate cantonists, when they were in their eighteenth year of regular military service, could in some cases be sent to cities where Jews lived.

The following case happened with a group of apostate cantonists in Vitebsk: in 1852, after 24 years of sending Jewish children to physical and spiritual annihilation 20 apostate soldiers from the Vitebsk garrison announced that they renounced the Russian Orthodox faith, given that, when they served in Perm, they were converted by force. The sermons of the priests had no effect. The soldiers did not want to hear about returning to the Orthodox faith. The matter came before the “Holy Synod,” which reported to the minister of war, blaming the Jews, because this certainly happened under their influence. The war minister decided to send the twenty rebellious Jewish soldiers to a city where there were no Jews and to issue a general order that in the future, converted soldiers serving in the regular army should be posted only outside of the Pale. Whether this case resulted in retribution against the Vitebsk kehillah is not known.[98]

Vitebsk gubernia, like all the other gubernias in the former Polish territories that came to Russia after the Partition, that is, the whole area of the Pale of Settlement, was required after 1852 to send twice as many recruits. Jews had to send every year 10 recruits per thousand, while the non-Jewish population from the same years had to send recruits only every other year, when it was the turn of the western part of the empire. (One year recruits came from the eastern part and the next from the western part.) In the order for the ninth “recruitment” of 1851, the people of Vitebsk received Nicholas's “kindness”–they were allowed to send young children instead of grown ones. But these so-called penalty recruits, whom they had to send according to the order of December 27, 1850, had to be older than 20. (This order required taking for one grown recruit

[Page 39]

2,000 rubles, which the kehilah was responsible for paying to the treasury in taxes.). The Vitebsk Jews could by no means present the required number of recruits for the last “recruitment.” The Jewish population in the whole Vitebsk gubernia in 1852 numbered 57,766 people,[99] that is, it would have had to supply 577 recruits, 100 from Vitebsk itself (at that time Vitebsk had about 1,000 Jews). In addition, they had to put forth three penalty-recruits for each recruit lacking from the previous “recruitments.” Nicholas once again showed his favor and a senate decision of May 11, 1851, extended the time for the Vitebsk gubernia to put forth recruits until January 1, 1852.[100]

Two years later, at the time of the tenth “recruitment” in 1853 in the western gubernias, when in the three gubernias of Pskov, Vitebsk, and Mohilev three recruits per thousand were demanded from the non-Jewish population. (In 1846 and 1847, because of an accidental exemption from the requirement to provide recruits.). But the Jews from Vitebsk and Mohilev gubernias were required to provide the same number of recruits as earlier–10 per 1,000. In other words, the Jews from these two gubernias were required to provide three times as many recruits as non-Jews.[101]

The privileged merchants were not required to supply any recruits. Those with property could buy their children out of recruitment, so that the whole difficult burden fell on the poor.

The famous, unhappy order of July, 1853, permitted the taking of passportless Jews as recruits. This caused terrible demoralization in Jewish life. The time of kidnapping began, which led to heaven offending injustices, such as kidnapping small children, ostensibly without passports, so that the Vitebsk-Mohilev general governor Urusov could not silence the great outcry, as he reports on the harmful effects of this order.[102]

Only with Nicholas' death in 1855 was there a softening of this awful recruitment law of 1827. Alexander II, in his order of August 26, 1856, abolished the horrible provisions of the law, namely, the cantonist system, the kidnapping of passportless Jews, and the taking of penalty-recruits for tax debts and for not

[Page 40]

providing recruits. With the annulment of the cantonist system, however, the order to provide recruits still stood, that is, the kehilah still had the duty to provide a certain contingent of soldiers. As a result, the institution of the kidnappers remained in effect until 1874, when general military obligations were instituted in Russia. Also, the order of 1856 to send the cantonists home had no great significance for Jews, because for Jews it anticipated only the freeing of soldiers who had not converted. Since only a few cantonists had retained their faith the result was that only a small number returned home, and the rest had to suffer through their cantonist Gehenna.