|

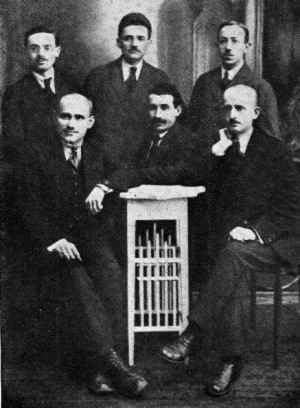

Seated: Zeitz, Avraham Yablon, Yakov Tenenbaum

Standing: Menashe Czarnobrode, Altshuler, Fishl Popowski

|

|

[Page 725]

by Y. Kaspi

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

The economic backwardness of Siedlce provided little possibility for even an average material life; the accompanying growth of anti–Semitism, which brought with it pogroms economic boycotts, and thuggish attacks–this difficult Jewish life gave birth to the realization that there was no place in the city for Jews. At the end of the nineteenth century, Jews throughout the whole czarist territory were caught up in two powerful emigration movements: “Am Olam,” which led to the United States and to South America, and “Chivat Tzion,” which led to Eretz Yisroel; that barren Jewish land could take in only idealists who were prepared to act selflessly while building a Jewish homeland. Consequently, there was also a large Jewish emigration to South America, and among the emigrants were a large number of Jews from Siedlce.

The first Jewish emigrants from Siedlce to the United States we find in 1895. The number of emigrants from Siedlce was still small, because at that time Jews in Siedlce considered emigration a sin. There were families who were ashamed of their sons and daughters who had gone to America, just as one might be ashamed of a convert in the family. There were cases when young people, fearing their parents' opposition to emigration to America, snuck away. The parents only found out later. People would joke about this kind of emigration;

[Page 726]

they would say that so–and–so son of so–and–so had gone to America when he just went to close the shutters. There were cases when parents went into mourning and sat shiva and said Kaddish for a son who brought on such disgrace by fleeing.

Quite different was the case of someone who went to Israel. Such a person was treated with honor.

According to reliable sources, the first Siedlcer to go to America was R. Moshe Fuchs, a watchmaker. After him came others but not all decided to remain there. Some returned.

Around 1906, when the Siedlce pogrom broke out there were about 180 Jews from Siedlce in the United States. After the pogrom, emigration from Siedlce increased and continued until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

The first person who undertook to organize the Siedlcers in America, in 1903, was Yitzchak Meir Eisenberg. He, together with sixteen other Siedlce Jews, established the “First Siedlce Support Association in New York.” During 1904 the number of members increased to about forty. The Siedlce association, under the influence of the new immigrants, joined the “Workers Circle.”

Siedlce Branch 53 continued to grow, so that in 1906 it had fifty members. The number of Siedlcers in America at that time was about 200.

The privileges of membership in Siedlce Branch 53 were as follows: a member could use the sick–fund; those with tuberculosis could use the sanitarium. Every ill member was entitled to receive thirteen dollars a week–eight dollars a week from the fun of the “Workers Circle” and five dollars a week from Siedlce Branch 53, for up to fifteen weeks a year; each member could be insured for up to a thousand dollars; in case of illness, each member and his family were entitled to free medical help, which came from the “Workers Circle” doctors. The Siedlce members could use all of the organizations and institutions that the “Workers Circle”

[Page 727]

had created, and after death they could receive a burial place in the “Workers Circle” cemetery.

Siedlce Branch 53, as is told in “The History of the Workers Circle,” from February of 1904 until 1925, paid out to the ill and needy $2,500; to the victims of the programs and the war $1,000; to HIAS $10 per year; in addition, a one–time payment to HIAS of $500 (paid in installments); and a general payment to a variety of organizations in America of $1,455. [See “The History of the Workers Circle,” by A. Sh. Sacks, vol. 2, 1925.]

Over time, friction developed between the founders of the “First Siedlce Support Association” and the leadership of “Siedlce Branch 53, Workers Circle.” Finally there was a split: on February 18, 1912, Moshe Garbowin, Chaim Leib Milstein, and David Spiegelman revived the liquidated “First Siedlce Support Association.” This organization was later renamed “The Siedlcer Society.” It considered itself to be a mutual aid society, as was stated in the form of a brochure. From this brochure we know the regulations of the “society”: they accepted members from 18 to 40 years of age according to the following terms: membership dues–$14.60 per year; for those over 40, $15; over 50, one had to be unanimously approved at a meeting in order to become a member.

The “Siedlcer Society” had a sick–bank. Anyone who was over 50 at the time of joining the society could not use the sick bank. An ailing member could get $9 per week for six weeks each year. If the member were ill for a longer time, he could receive $4.50 for another four weeks. When a member became ill, according to the rules, he had to give written notice. Twice a week, a special committee would visit him

[Page 728]

to determine whether the doctor's certificate should be accepted so that the member could make use of the sick–bank.

The “Siedlcer Society” employed a doctor who gave free medical help tot he members' families. When a member sat shiva, he was entitled to receive 49. In case of a difficult financial situation, when a member needed support, a special committee would visit to evaluate his financial situation and designate support. When a member got married, the “Siedlcer Society” sent a delegation to wish him “mazal tov” and to bring a gift of not less than five dollars. In case of death, survivors received an insurance payment of $200. Of this, $100 came from the society's treasury and $100 was raised by the members, not as a donation but as a duty. If none of the survivors accepted the responsibility of erecting a gravestone, the “Siedlcer Society” put up a stone and the expense was deducted from the $200.

The statutes of the “Siedlcer Society” also described a whole list of committees, such as: an examination committee to consider the applications from candidates, a finance committee, an illness and shiva committee, a burial committee, an honor court, and so on.

The rules went into effect on January 12, 1921, but then in 1917 the “First Siedlce Support Association” purchased its own cemetery in the “Bais David” cemetery in Jamaica, Long Island, New York. The Siedlce cemetery was surrounded by a small park that was behind a marble gate, beautifully made, with iron doors and the inscription: “First Siedlce Support Association.” The cemetery cost $1,600, and the gate cost more than $1,200.

The “Siedlce Branch 53” and there Siedlcer Society” had two fundraising events: the yearly ball, which was organized every winter by there “Siedlce Branch 53” and the yearly picnic, which was organized each summer by the “Siedlcer Society.”

[Page 729]

In 1913–1914, an attempt was made to establish the “Siedlcer Young Men's and Ladies' Educational Club” (a club for young people). It began with about thirty members. This club existed only for half a year, until the outbreak of the World War in 1914.

During the First World War, the Siedlcers created the “Siedlce Relief Committee,” whose goal was to help the Jews of Siedlce who were victims of the war.

At the founding of this committee, it was decided to send delegations to “Siedlce Branch 53” and the “Siedlicer Society” to enlist them in the relief effort by sending representatives to the new organization so that it could speak authoritatively in the name of the whole Siedlce population. Both organizations at first were indifferent about the matter, but when the American newspapers began to publish news about the catastrophic lot that befell Siedlce, the indifference disappeared and the “Siedlce Relief Committee” took off.

The “Siedlce Relief Committee” formed an amateur theater group, consisting of: Eliyahu Sonnshein, Louie Altfeder, Max Ridel, A. Levartowski, Wishnia, Sarah Kindman, Aaron Rozen, and Isidor Azet, They put on plays, with the admission fees going to war victims. During one production, Sara Kindman sang the song “Give a Donation” and choir in the wings accompanied her. After all expenses, $500 remained for the relief.

In May of 1917, the “Siedlce Relief Committee” purchased a theater production called “Shema Yisroel” from Ossip Dimov. The undertaking brought in much money. This activity was interrupted on April 6, 1917 when America declared war on Germany. A little later, the “Siedlce Relief Committee” resumed its activities on behalf of Jewish war victims in Siedlce.

With the help of the “Joint,” the “Siedlce Relief Committee” sent notable sums of money to Siedlce.

In order to increase its income, the “Siedlce Relief Committee” purchased from Maurice Schwartz art theater

[Page 730]

a production of Peretz Hirschbein's “Green Fields,” which brought in much money. The “Releif Committee” conducted activities until the end of the war, bringing in $5,000.

At the conclusion of the peace, in 1921 the “Relief Committee” sent Avraham Yablon to Siedlce with $2,000 for various organizations and $5,000 for relatives.

In Siedlce a committee was put together, including: Yakov Tenenbaum, Menashe Czarnobrode, Yitzchak Zeitz, Yitzchak Altschuler

|

|

Seated: Zeitz, Avraham Yablon, Yakov Tenenbaum Standing: Menashe Czarnobrode, Altshuler, Fishl Popowski |

[Page 731]

(Dromi, living now in Israel). The committee, along with A. Yablon, collected the money. When the envoy returned to America, the “Siedlce Relief Committee” was dissolved. From time to time collections were made by individuals in America to support Siedlce institutions, particularly the “Aid to Orphans.” From 1921 to 1932, about $1,500 was sent to Siedlce in this way.

The Siedlcers in the United States also did local relief work. Siedlcers in 1920 founded i8n America a charity fund called the “Siedlce Finance Corporation,” which had 250 members. Each member contributed $25, and in case of need could get a loan. After a few years, the “Siedlce Finance Corporation” was dissolved.

In 1925, the “Siedlce Society” created a loan fund, which assembled a sizable amount of capital. This fund was active for a long time and contributed greatly to community needs.

On November 19, 1930, the “Siedlce Branch 53–Workers Circle Women's Club” was established, which, for various reasons, was reorganized on November 2, 1931 as the “Independent Siedlce Women's Club,” with over 70 members.

In 1952, the “Siedlce Branch 53” decided to contribute funds to the creation in Israel of a building to immortalize the memory of the martyrs of Siedlce. A. Kaddish, a special activist in in “Siedlce Branch 53,” pledged a large sum to this cause, and together with the assigned sum, a total of $14,000 was given to the “Workers Histadrut” in Israel. The “Histadrut” took on the responsibility to erect in Acco a cultural center containing a movie theater, a small theater, and amphitheater for the summer, with lessons in Hebrew and rooms for the offices of the local workers council. According to the estimate, the building and its furnishings would cost nearly 80,000 pounds.

[Page 732]

On Chol Hamoed Pesach, 1953, in the presence of a large crowd, representatives of the workers council of “Histadrut” and a committee of Siedlcers in Israel all gathered in Acco, occurred the solemn laying of the foundation stone for the building. All of the speakers emphasized the importance of the building being built in the name of the martyrs of Siedlce and being located in Acco, a city of new immigrants, a gathering of exiles.

|

|

| Fishl Dromi (Popowski) greeted at the laying of the foundation stone |

|

|

| How the Cultural Center will look when it is completed |

[Page 733]

|

|

| The sign of the cultural center |

Fishl Dromi spoke on behalf of the people of Siedlce in Israel. He emphasized the significance of the great deed of establishing in Israel a remembrance for Siedlce's martyrs who suffered so much in exile.

France

The emigration of Siedlce Jews to France also began in 1906. After the First World War, emigration increased. The emigrants were mostly leather workers, who suffered from crises in the business and fled from the persecutions of the existing Polish regime, which went after communists and even Jewish socialists.

Around 1925, the Siedlcers in Paris formed a committee to give aid to Jewish communists who languished in Polish prisons and to help the families of the detained. Such help was, in fact, provided. Money was sent to Siedlce. This action prompted other activists to create a Siedlce union to deal with general affairs for all who came from Siedlce.

After the Second World War, the surviving Siedlcers in France returned to their homes. Many Siedlcers were brought to France by the Nazis. The survivors were naked and barefoot. The existing Siedlcer union undertook a relief program for the remnant from Siedlce. The children of Siedlcers, orphans, were taken into protection by the union. The new arrivals to France from Siedlce received support.

The Siedlce union, although it was associated with the Left, defended Israel

[Page 734]

|

|

| The inscription on the monument with the names of Siedlcers, murdered and martyred, in Paris |

[Page 735]

|

|

| The procession to the unveiling of the monument in Paris |

|

|

| Siedlcers in Paris bring the urn with the ashes of Siedlce martyrs for burial |

in the great battles fought by the Yishuv for independence. A sum of 200,000 francs was raised for the Haganah.

The following figures illustrate the activities of the union in 1945–1948:

| Support for 434 people | 699,650 francs |

| Clothing for children | 360,050 francs |

| Summer dwellings for children | 169,650 francs |

| Housing for children | 480,000 francs |

| “Haganah” | 200,000 francs |

| Total | 1,909,350 francs |

Aside from the above–mentioned countries, Siedlcers were found in other countries, though not organized in unions–in Australia, in South American countries, in Canada, and in South Africa. Siedlcer Max Kaczynski, one of the greatest South African philanthropists, is there. He donated great sums for the building of Israel. He gave the Hebrew University in Jerusalem many thousands of pounds. In 1934, Kaczynski spent ten months in Israel and learned Hebrew.

[Page 737]

by Dov–Ber Blechstein (Jerusalem)

Translated by Yisrael Tabakman

The Jews from Siedlce in Belgium have taken on a prominent place in Jewish communal life. There is not a single society or party in which the Siedlcers are not represented or take part in the practical work.

The odyssey of Siedlce's Jews to Belgium began in the years 1927 to 1933. The emigrants from Siedlce actually wanted to go to America, but due to a lack of funds or for other reasons, they were stuck for the most part in France, specifically in Paris, and a small number—in Belgium, mostly in Brussels, with a few in Lieges or Chareroi.

Those Siedlcers who settled in Belgium did not change the professions they had followed in Siedlce. They organized according to their crafts: tailoring, shoemaking, gaiter making. A small number of gaiter sewers turned to “Moroccaneria,” that is, to making women's pocketbooks, which was then developing. There were also some bakers, who organized themselves in the provinces.

At the founding meeting of the Siedlce Landsmanshaft in Brussels (I do not remember the year), about 100 people gathered; we estimated then that there were more than 200 families from Siedlce in B Belgium. It was decided at the meeting that all the business of the Landsmanshaft would focus on Siedlce and its institutions.

The Siedlcers in Belgium, as I have said, were

[Page 738]

involved in all the local institutions and parties that the emigrants had fashioned. Many were members of the “Solidaritat” Society—an organization of the Jewish communists. A greater number belonged to the “Mutual Aid” Society and worked actively in the Peretz schools of there leftist “Poalei-Tzion.” Very few belonged to the “Bund.” I will mention several community activists in Belgium whom I knew personally.

When I arrived in Belgium, in 1927, I met Meir Sluszni. When he was young, he belonged to the Bund. There, in Brussels, he ran a printing shop, where he worked all alone. He was an outstanding cultural worker, he spent his free time in that cause. For a long time he as the secretary in the Jewish Central Handworker organization in Brussels. Sluszni was known particularly because of his son, a pianist, who was famous throughout Europe and played in the. Belgian royal court. Several times he was invited to England, France, Switzerland. After the liberation, Sluszni became a member fo the “Poalei-Tzion” and assumed all the cultural labor, in which he is still active.

Avraham Gutnowski came to Belgium with his family in 1928 and settled down in his craft—sewing gaiters. His wife Rivkah—a leading member in the Siedlce “Bund,” helped with his work. They had difficulty earning a living. Avraham Gutnowski also wrote poems with a socialist bent. His poems were published in Yiddish papers and journals in France, such as the “Free Press” in Paris and “Our Word” in Brussels. The Gutnowski family suffered terrible misfortunes: at the time of the Spanish Civil War, their eldest son enlisted in the International Brigade and fell at the front in Spain. During the Hitlerian occupation, a second son joined the Belgian partisans. The Gestapo captured and tortured him. The older Gutnowskis survived difficult times in Hitler's years, but they never gave in to the pain and troubles. After the liberation, he continued to write and took an active role in raising the monument in Belgium to the murdered people of Siedlce.

[Page 739]

Meir Tabaktan, born in Siedlce in 1927, left his parents when he was fifteen and after a short time in France came to Belgium. With his Poalei-Tzion outlook, he was one of the most active comrades of the Borochov-youth in Brussels and was later the leader of that group. In the Poalei-Tzion Party he was especially active in the area of sports, and he was one of the founders of “Shtern,” the Jewish sport club and he led it to being one of the strongest sports clubs in Brussels. In 1935, Mr. Meir was elected to the party committee and did much important work for them. The war broke out and in 1940 Mr. Meir was one of the founders of the popular organization in our community—“Mutual Aid.” The younger community workers threw all their energy into helping Jews returning from France.

In 1942, when Hitler's monsters began to rampage on the Jewish streets in Belgium, Mr. Meir was one of the most active Jewish resistance fighters against the Germans. He came in contact with the leading Belgian personalities in the resistance movement and was named by the Poalei-Tzion Party Committee to lead negotiations about allowing a group from Poalei-Tzion into the partisan movement. At the end of 1942, while on party work in the street, he encountered a police raid, and one of the S.S. men recognized him. Mr. Meir was badly beaten and sent to the Molin [?] camp. When they were preparing the deportation to the death camp, he planned and organized the escape from the deportation train. Mr. Meir worried over the gear to make holes in the floor of the wagon. The plan succeeded . About 200 Jews, including Mr. Meir, escaped from the train. Because of injuries from a bad fall from the train, he had to spend several days in a hiding. When he had healed a bit, he returned to active resistance work. Because he was responsible for the illegal press of the Poalei-Tzion Party, he often kept hundreds of copies of “La Libre Belgique,” “Flambeau,” “Fran,” “Undzer Vort,” “Freie Gedank” (illegal publication of the left Poalei-Tzion in the Flemish language).

A short time later our beloved Mr. Meir was captured. Against he wanted to escape, but he could not.

[Page 740]

He was deported on the 22nd transport, and again he jumped from the train. When he returned to Brussels, his friends advised him to remain in hiding, but Mr. Meir would not submit to such a luxury; people had to save Jewish children, Jewish parents. Again he went on party missions. This time he put up posters against the occupiers, calling on the Belgian people to help the Jews who stood with them in a common battle against the enemy.

On January 1, 1943, Mr. Meir was packing food for Jewish children in hiding. They were together with Belgian children, who would also be happy with a “Saint Nicholai” gift. But the Gestapo interrupted his life and life-giving activities. This time a Gestapo man recognized him as one of the escapees, so with a red band on his arm, our Meir was deported to his death.

Aside from those people whom I have mentioned, those active in community affairs in different ways in Belgium were Hersh-Leib and Bineh Srebrnik (now in Israel). Hersh-Leib Srebrnik was an active member in the handcraft club and in other community committees in Brussels. Also his wife, Bineh, was an active member of “WIZO,” Keren Kayemes, “Mutual Aid,” and of the Peretz School. She was devoted to raising money for all of these organizations

Feivel Garbiesz (now in Australia) was an outstanding worker in a number of organizations and was generous in community matters, though he had to work hard for himself. Avraham Gutowski (still in Brussels) devoted all his energy to the Siedlce Landsmanshaft and gave tremendous help to the erection of the monument to the murdered Siedlcers in Belgium. One more Siedlcer will I recall from Brussels who is no longer among the living—this is Yekel Gottesdiener. I knew Yekel Gottesdiener in Siedlce when I was young, though then I knew him as “Yenkele Rachtshes,” and I would often encounter him at Yakov Moyshe Morchbein (or Greenberg) playing chess. I knew then that he was one of the best chess players, but in Brussels I found a totally different Yakov Gottesdiener, a Jew of stately appearance, a fine European Jew with a broad worldly outlook

[Page 741]

on all worldly questions, whether related to general party matters or Jewish problems. He was respected in a number of Jewish circles in Belgium. He was a consciously free-thinking Jew, but at home with his family and among his people he was a strongly traditional Jew.

I will mention another important matter: the activities of the Siedlcers in Belgium to benefit Siedlce itself. In the years 1940-1941, the Siedlce Landsmanshaft was in close contact with Siedlce by sending letters and packages to the Siedlce ghetto, and we operated as the central post office for all Siedlcers in the western European countries; from England through Switzerland and from Switzerland to France and Belgium. Letters also came from America to two addresses that were known abroad: these were my address and, I believe, the second address belonged to Hersh-Leib Srebrnik. Many letters came from lots of foreign countries. The letters contained things to be sent on to families: tea, pepper, month, and questions about whether their families were still alive. In the letters were were international postal coupons and sometimes money. We worked around the clock trying to do what they asked. We had to fix the envelopes, rewrite the addresses accurately over the pepper or the tea or whatever else was in them. And there were hundreds of such letters.

For the Siedlcers, this was among the most sacred work in their daily lives. We imagined that here, in the Siedlce ghetto, we were saving people from death. And the letters we received back, which were not many, we immediately sent on to those who awaited responses. Thus we worked day and night without growing weary until the beginning of the Hitlerian repression in Belgium. We wondered that the Gestapo would leave us in peace so that we could carry on with our work. Many letters arrived having been censored by the Gestapo, but nothing changed.

At the beginning of 1942, when the wild persecution of Jews in Brussels began, Sluszni and I received summonses to come to the Gestapo on Rue Louise; we knew that one had to obey such a summons…but I did not think that Sluszni should go because he was already

[Page 742]

an older man, so I was amazed when I encountered Sluszni there. And when we were taken in to the leader, an ugly bandit, we encountered other Jews who had been summoned. We were summoned because of the Siedlce Landsmanshaft, Sluszni as the chair and me as the secretary, so that we could explain the duties of the Siedlce society. Know, then, that we explained that this was only for Siedlce, to help the institutions there. They suggested that we continue our work. We excused ourselves with the excuse that we were the only two left. When we got back home, our families burst into tears.

Meanwhile I was sure that the Gestapo bandits had “invited” us, that is ordered all representatives of Jewish organizations to come, so that they could be sure who were the representatives of the parties and the organizations in the Jewish community of Belgium. I told them that in Belgium there existed a council of Jewish organizations in which were registered all all societies and parties. On May 10, 1940, when the Germans occupied Belgium, on the second day, all members of the council left Belgium and abandoned the whole archive. They did not even lock the office. The Germans confiscated everything and so became aware of all Jewish movements in Belgium.

Right after my visit with Sluszni to the Gestapo, one morning we received an order to come with another person to the Gestapo as representatives of the “Leftist Poalei-Tzion.” My son Meir, too, was appointed the representative of the “Shtern” sportclub.

With the increased repression, when Jews could barely continue living in Belgium and everything was being destroyed, the Siedlce Landsmanshaft ceased to exist.

Shortly after liberation in 1945, there was the first coming together of a few Siedlcers: Sluszni, Tabakman, Srebrnik, Gutnowski, Garbiarsz, Mendel Piekarsz. We were certain that among the 28,000 Belgian Jews who had been exterminated there were more than 100 from Siedlce who were killed. We decided to revive the

[Page 743]

the Siedlce Landsmanshaft. All of our work focused on the plan to erect a monument in Belgium for the Jews of Siedlce who had been killed. The work was quite difficult. Worn out from work in the underground and having the responsibility of restoring the living conditions of the Jewish settlement in Belgium, for whom we had risked our lives, was a bit too hard to devote oneself to a separate task like the monument. And besides, who could even think about it? After such a great catastrophe, when the whole nightmare appeared before our eyes, when the small number of Jews who remained alive in Belgium were bunched together in one spot, in Brussels, without a shirt on their backs, where they needed help every day, like food, clothing, doctors, medicines, a roof over their heads, one would have been regarded as crazy to speak about a monument for murdered Siedlcers; it would have seemed like foolishness. But the Siedlcers decided to erect such a monument, and they carried out the decision. That represented a lot of work. The question was, where to build the monument. It was

[Page 744]

decided to build it in the Jewish cemetery. I was selected to intervene with the Jewish authorities about a place for the monument. On the monument were to be, in addition to the names of the murdered, also their pictures. When I came to the first meeting of the authorities with a plan and asked for a plot of two meters for a monument of black marble with a pedestal, with names, with pictures of the murdered Siedlcers, I was listened to in silence; and then everyone at the meeting addressed me this way: “How can you, Mr. Tabakman, ask that in a Jewish cemetery we should erect a monument with pictures, just like the gentiles?” After a long discussion, they called for a meeting with the Brussels rabbi, and if the rabbi approved, they would allow it.

I wasted no time and hastened to the rabbi (whose name, sadly, I do not remember, though he now lives in Tel Aviv) and delivered my request, explaining to him that if he would approve, then the authorities would allow it. After a long talk, the rabbi said, “Since I know about your suffering in Hitler's time, your untiring work in the present, after liberation, for the welfare of the Jewish community in Brussels, I will approve, with one condition: no photos.” He asked that I be satisfied. I agreed and settled things with the rabbi. I drew up a contract with the authorities for a plot of two meters at the nicest spot in the Jewish cemetery of Brussels. I reported this to the Siedlcers, and then began the real work of collecting funds and carrying out the plan. That was hard work, but we did it all heroically. Every Siedlcer was involved and helped turn the idea into reality.

With great effort and work, we were able to eternize the murdered Siedlcers, and the monument stands in the nicest spot in the Jewish cemetery of Brussels. Underneath the monument are buried bones of Jews from Lukow that had been scattered around the city of Lukow and were brought by people from Lukow. There are also names there, particularly of fallen Siedlcer partisans. On the day when this grand monument was unveiled, all of Jewish Brussels attended

[Page 745]

and filled the whole cemetery. This was one of the saddest gatherings that I saw after the liberation. This was my last activity with the Siedlcers before I traveled to Israel.

It is my wish that Siedlcers from the around the world should consider putting up a large monument in the “Forest of Martyrs” in the hills of Jerusalem.

|

|

| The monument for the Siedlcers in Belgium |

[Page 746]

|

|

Sitting (left to right): Yisroel Vinograd, the proofreader Moshe Konstantinowski, Moshe Yudengloibn, Moshe Federman, Hersh Abarbanel Standing (left to right): Bunim Finifter, Yitzchak Bistrowicz, Avraham Creda, Feivel Englander |

by Moshe Yudengloibn

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

On April 20, 1930, a group of natives of Siedlce gathered together in the home of Mr. Bezalel Rosenbaum. These included: Hershel Levin, Moshe Federman, Shimon Kirshman, Gedaliah Solarsz, Yosef Rosenbaum who was later killed in Poland by the Nazis.

This group of Siedlce natives took on the responsibility of founding a union of emigrants from Siedlce, so that the newly arrived could find a warm corner and not be strangers in a strange land. They would care for the new arrivals, help them in case of illness, and so on.

After a discussion, they decided to establish an association of Siedlce natives, and they elected a committee consisting of Hershel Levin, Moshe Federman, Bezalel Rosenbaum, Shimon Kirshman, and others.

After their first meeting, they put out an announcement to all Siedlcers in Buenos Aires that they should join the group. This appealed to a certain number of Siedlcers, but the majority remained outside the association. The committee made the greatest efforts to publicize and declare the need for such an association. This work paid off a little. For a little while, the association met in the home of Bezalel Rosenbaum.

When the association reached a hundred members, it moved to the premises of the Jewish-Polish Association and began to undertake its activities. They set out to realize the duties they had written down. Different undertakings were organized to attract all the Siedlcers of Buenos Aires, to approach them, to familiarize them, and to create a warm atmosphere for them. The Siedlcers

[Page 748]

began to feel homier, closer, and they often got together.

Meanwhile, more Siedlcers came to Buenos Aires. The association was for them, from the beginning, a home. People helped some with a kind word, some with finding work or with a big of advice about what to do. In time, the association grew and began to think about creating a credit union, which was quite necessary at that time. The newly arrived Jews from Siedlce, as well as local residents, needed credit. The local banks required guarantees from highly-placed people, and at that time there were few Siedlcers who could give such guarantees.

At a specially called meeting, the question of forming a credit union was discussed. The gathering showed great interest in the matter. They discussed how to pay for sharess and what the price should be.

It was decided to make the price for a share 25 pesos and a loan limit of 100 pesos. An ad hoc committee was selected to solicit shareholders. Many members signed up for shares, some for one, some for two, and so on. A considerable sum was raised at the meeting, and the committee got down to work.

After much effort, the credit union finally opened and made its first loans. This had a huge effect on the Siedlcers and they became ever more interested in the activities of the credit union. In time, the credit union got credit from the Jewish Folkbank, which allowed it to give even bigger loans. Loan payments started to pour in, so the credit union's activities could grow.

Enough money was coming in that Siedlcers of better standing who needed more money than the banks would allow approached the credit union, and this resulted in a difference of opinion on the committee. Some maintained that the requested sums were not sustainable, because the bank was not yet in a position to give such loans. It needed more time to practice by giving smaller sums, according to the bank's abilities, because

[Page 749]

in fact the bank had been created to give loans of up to 100 pesos. But the second group on the committee (the majority) did not want to take into account the actual situation and decided to give the requested sums as a larger bank. would have. The result was that recipients of the large loans did not pay—the coffer remained empty; they could no longer give even the smaller loans.

A number of Siedlcers began to mutter that there was no money. The shareholders who had shares and had taken no money lost trust and wanted their investments back. Two sides formed, and each side blamed the other. The apathy of the Siedlcers toward the association and to the bank increased, and it went bust. The committee, which had taken money from the Folksbank on their personal responsibility with promissory notes had to come up with funds to cover the loans, because no more money was coming in. The large borrowers were not repaying were deducting the costs of their shares. The coffees were empty. In this situation, it emerged that the shareholders, who had two or three shares, would lose the money for their shares. It must be stressed that at that time the shareholders had nor other funds. The situation led to the collapse of the association and of the bank, leaving a bad taste with all of our Siedlcers.

As time passed, more people from Siedlce arrived. The new arrivals would gather with people they had known at home—in private dwellings, where they could talk, recall their old homes, and think about who they could take away from there. The resident Siedlcers conducted community life in meeting spots, each according to his inclinations: home in the workers movement, others in Zonist circles; each found his own spot. Many remained as they had been in their old homes—apathetic toward everyone; they were interested in nothing, not their fellow Siedlcers, not in the community, and not in their old home. But those who were active in the community of our Siedlcers produced a number of people who were active in the Argentinian Jewish settlement.

[Page 750]

After Hitler's Extermination of the Jews

When the bloody Second World War came to an end and Jews throughout the world knew of the great misfortune that had befallen European Jews, the terrible news came as well to us in Argentina about our home town of Siedlce.

We immediately met and began to assess the situation. The question arose of how to to create aid for our surviving sisters and brothers. The horrible misfortune united all of our Siedlcers. Many of them came prepared to help all who were in need. Immediately a committee was formed to conduct the aid project. The committee consisted of the following people: Avraham Kreda, Moshe Federman, Tz. Rosenbaum, Mosher Yudengloibn, Yoel Levin, Hershel Levin, Mendel Saperstein, Meir Malawnczik Sh. Kirshman, Mottl Sckerrmsan, Itzl Rosenbaum. Our friend Avraham Kreda was elected to preside. The secretary was Moshe Federman, the treasurer M. Saperstein. A women's committee worked alongside the men's.

At the first large meeting, the committee immediately collected money for the aid fund. The committee members were the first to contribute. Everyone followed their example. A large sum was quickly raised.

After the meeting, the committee sought to visit every Siedlcer whose address was known. Thus it was done to broaden the action so that the help would be larger. At that time it was incumbent to amass a large sum of money. Meanwhile, letters arrived letters of a collective nature from the cities of Lodz, Siedlce, and others.

We prepaid six crates of clothing for men, women, and children, of which 90 percent was new, gifts from our comrades. The six crates of clothing were sent on a Polish ship. Later we

|

|

| The certificate making permanent the “Siedlce Kehillah” in the Golden Book |

[Page 752]

received a response that they had received them and divided them up.

There were some who asked for help in leaving Poland and whether people would receive them in Argentina or help with their papers. We did for them all that was possible. We helped come to Argentina: a woman with her child, a family of three, and we helped them get settled. We also gave material help to many Siedlcers who could not bring over their surviving families.

A little later, letters began to arrive from the D.P camps asking for help in the form of food packages. We quickly sent packages to wherever it was possible. We also sent 500 dollars to Paris for the Siedlce orphans and material help to the appeals of individuals Siedlcers in Paris. To Israel we sent 100 pounds to the Siedlcer Landsmanshaft , and especially for individuals from Israel who had come to us, we sent food packages.

Also for the Haganah we contributed 1,000 pesos. Thus we conducted our aid work to the maximum and in proportion to our membership.

Thus ended the financial aid.

After this activity there was a pause in the activities of the association. But the committee continued its work. It organized undertakings from time to time, eternized the Siedlce Kehillah by having it registered in the Golden Book on the first anniversary of its origin.

The committee had the idea of issuing a Yizkor Book that would be a monument for our destroyed community. We gathered materials for such a Yizkor Book. The committee went to Siedlcers in many countries asking them to send pictures and newspapers that had a bearing on Siedlce and also to write memoirs. We, on our side, were ready to do everything to see that such a book appeared, but we lacked materials. Finally from Israel came the surprising news

[Page 753]

|

|

| Siedlcers who attended the announcement of the publication of the Siedlce Yizkor Book and who paid the first installments |

[Page 754]

that they had the required materials, memoirs, photocopies, and so on, and that they were prepared to join us in issuing the Yizkor Book.

Intensive work began immediately on preparing these materials.

The visit of our comrades Hershel Barbanel to Israel hastened the appearance of the book. He discussed it with our Siedlcers in Tel Aviv and prepared the plans for publication.

Our Siedlce colleagues in Israel deserve the greatest recognition for their true extraordinary work in organizing these rich materials, for which their hands should be blessed. This book should be a great honor to all Siedlcers throughout the world.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Siedlce, Poland

Siedlce, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 11 Sep 2021 by LA