|

|

|

[Page 2]

|

|

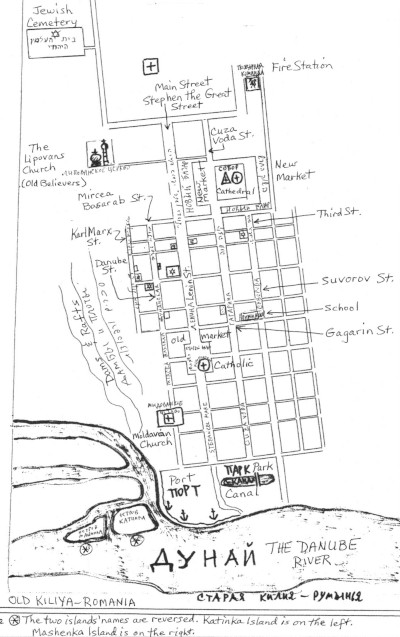

| Map of Kiliya – Unfortunately, we could not find a map of the town. We could not even find a postcard, photos of the streets and of interesting sites in any Kiliya stores. This map was drawn only from memory. L.K. |

[Page 3]

[Page 4]

Kiliya is a small town with an ancient history, situated close to the area where the Danube spills into the Black Sea. This great river that crosses eight countries in Europe becomes extremely wide and deep here to allow a natural port and the navigation of large cargo ships. Kiliya was always inhabited by a diverse population of Russians, Ukrainians, Lipovans, Moldavians, and Jews.

From 1920–1940, 2400 Jews lived in this community: merchants, craftsmen, rich and poor, middlemen and porters who worked together with the Russians, carrying bags of 50–60 kg (80–96 lb).

Bessarabia was annexed by Romania in 1918. The Romanians did not develop the town; they did not build roads or railroads or bring in clean water or sewers. In a town of 20,000 people and with 50,000 people in the rural area, there was only a four-class gymnasium for ages 10–13. Every winter the river froze, and the town became isolated for almost three to four months.

The kehilah (Jewish Community) was well-organized. There were four beautiful synagogues, a Tarbut (Culture) School, a kindergarten, various youth organizations, a library, a theater club, sports clubs, an orchestra of woodwinds and brass, a credit union, two old-age homes, and lots of social activities, all organized by the Jewish Community. The Zionist activities consisted in collecting funds for Keren Kayemet, Keren Hayesod, and many Halutzim (Pioneers) activities. Until 1940, a number of families, pioneers, and students moved to Eretz Israel.

In 1940, when the Russian Army occupied Bessarabia, the Stalinist regime shut down all Jewish Community activities according to paragraphs 38 and 39 of the Soviet law, and lots of “non-loyal” Jews were banished to great distances from which they did not return. The four synagogues, the school, and other community institutions were closed. This policy was ad hoc and not equally applied; for example, out of the six churches, four were left, and they are still functioning to this day.

The Holocaust

In June 22, 1941, the Nazis invaded and occupied Bessarabia. In July 18, 1941, the Soviets left the town without organizing any help for the Jews to flee. We know who spilled the blood of the 1800 Jews of Kiliya—old people, women and children! In the first two weeks after the invasion, the Romanians killed more than one hundred Jews on the town streets and also others who took shelter in the Great Synagogue. On September 25 and 30, all the Jews were deported from the town.

On the way to Tatarbunary, 118 Jews were murdered (see the article on the “Uprising” of Miculescu and Mareiu). In Odessa, 80 people were murdered. On the way to Bogdanovka, another 300 were killed, mostly old and sick people and children. From December 25 to 28, 1941, more than 1,000 people were murdered in cold blood, together with another 54,000 Jews from Bessarabia and the Odessa region. Only 180 survived, among them only eight Jews from Kiliya.

May their Memories be blessed forever!

After 50 years, a long time after the Holocaust, the survivors of Kiliya who live in Israel, veteran citizens and new immigrants, got together to remember the community for the next generation.

We will not forget and not forgive the murderers.

Only a few war criminals were tried in Romania, and they were given light sentences. In the Ukraine, 22 war criminals were sentenced to death during the two trials. It is clear that there are still criminals who are in hiding and who ought to be punished.

Recently, the Soviet regime is allowing many Jews to leave the USSR for Israel, and this is a good thing. The present Kiliya municipality must remember the 1800 Jews murdered by the Romanian Nazis and Fascists and erect a monument in the center of the town and restore the Jewish Cemetery.

December 1990

The Editor

[Page 5]

Kiliya is a small, ancient town, founded 2,700 years ago at the mouth of the Danube near the Black Sea. This great river that crosses eight countries in Europe becomes extremely wide and deep here, allowing for the development of natural ports for large cargo ships.

Kiliya has always been inhabited by a diverse population of Russians, Ukrainians, Lipovans, Moldavians, and Jews.

From 1920–1940, 2,400-2,500 Jews lived in this community: merchants and craftsmen, rich and poor, middlemen and porters who worked shoulder-to-shoulder with the Russians, carrying bags of grain weighing 50-60 poods (1,800-2,100 pounds).

Bessarabia was annexed by Romania in 1918, but the Romanians did not develop the town. There were almost no roads or railroads. In a town of 20,000 people and with 50,000 more people in the rural area, there was only a four-class gymnasium. Almost every winter the river froze, and the town became isolated for several months.

The Jewish community was well organized. There were four beautiful synagogues (the “main” one on Bolshaya Dunayskaya Street was considered to be the most magnificent building in the city), a Tarbut (Culture) School and kindergarten, various youth organizations, a library, a theater club, sports clubs, the Maccabi orchestra of woodwinds and brass, a credit union, two old-age homes, and on top of all that, the social activities of the Jewish Community.

Zionist activities also started up, including the collection of funds for Keren Kayemet and Keren Hayesod. By 1940, approximately 50 families and chalutzim (pioneers) were able to move to Eretz Israel.

In 1940, the Soviet Army was received warmly by the Jewish population, but the Stalinist Soviet regime halted all organized life of the Jewish population. Due to arbitrary tyrannical measures (paragraphs 38 and 39), several hundred “non-loyal” Jews were exiled. Some of them never returned. The four synagogues, the school, the library, and other Jewish community institutions were confiscated. This policy was clear discrimination; out of the six churches, four were left in Kiliya, and they are still functioning to this day.

Terrible days of calamity approached. On June 22, 1941, the German-Romanian Nazi troops invaded and occupied Bessarabia. On July 18, 1941, the Soviet Army left Kiliya. During those 26 days, there was no escape arranged for the Jewish population. WE KNOW WHO SPILLED THE BLOOD OF THE 1800 JEWS OF KILIYA, INCLUDING ELDERLY CITIZENS, WOMEN, AND CHILDREN! In the first two weeks after the invasion, the Romanians killed more than 100 Jews on the town streets. At night, Russian neighbors took those who had been shot and killed to the Jewish cemetery, where they are buried in a mass grave to this day.

On September 25 and 30, all the Jews were deported from the town (most going on foot). In TATARBUNARY, 118 more Jews were murdered (see the report document from Colonel Miculescu). In ODESSA, another 80 people were killed (shot/hung). On the way to BOGDANOVKA, approximately 300 were killed, mostly the elderly, sick people, and children.

On December 25, 26, and 27, there were horrific organized shootings of 54,000 Jews from Bessarabia

[Page 6]

and the Odessa region, including more than 1,100 Kiliyans. In 1944, only 180 were still living, among them only eight from Kiliya.

T'hay nafsho tzrurah b'tzror hachaim

May their souls be bound to the bond of life!

After a long delay – 50 years after the tragic annihilation of the Jewish population of Kiliya – the survivors of Kiliya who live in Israel organized a time to get together to memorialize our people for the next generations.

WE WILL NOT FORGET AND NOT FORGIVE THE MURDERERS!

Only a few of these executioners were tried in Romania, and they were given light sentences. In the USSR, 22 war criminals were sentenced to death during two trials. We are sure that there are many criminals who are in hiding to this day, and the arm of justice must reach them. IN BOGDANOVKA THERE IS STILL NO MEMORIAL TO COMMEMORATE THE 54,000 JEWISH VICTIMS OF THE NAZIS.

We are glad that within the last year, the Soviet regime has allowed many Jews to leave the USSR for Israel. We would also like to believe that the local Soviet authorities will erect a monument in the center of the town in honor of the 1,800 Jewish Kiliya residents murdered by the Nazis and will restore the Jewish Cemetery.

|

|

| Kiliya. General View, 16th Century |

[Page 7]

| Berger (Rozenblat) Rina | In Memory of her parents: Ester and Khaim Rozenblat and the entire family who perished in the Holocaust, z”l |

| Grinberg Chana | In Memory of her parents: Berta and Yacob Finkelshtein, z”l |

| Weinshtein (Kuslitsky), Polya | In Memory of her brother Froike and parents Feiga and Itzkhak Weinshtein, z”l |

| Weisman, Shaike | In Memory of his parents: Chana and Abraham Grinberg, z”l |

| Zalman (Katz), Batya, Canada | In Memory of her parents: Chana and Israel Katz, z”l |

| Zohar, Itzkhak | In Memory of his parents: Sara and Kopel Zisman, z”l |

| Khaimovich, Tanya | In Memory of her husband Misha and his parents Shifra and Yekhiel Chaimovich, z”l |

| Yatsiv, Zeev | In Memory of his parents: Hinda and Abraham Konstantinovsky, z”l |

| Yatsiv, Yehuda | In Memory of his parents and his uncle Berl Konstantinovsky, z”l |

| Lerner, Yosef | In Memory of his parents: Rivka and Yeshayahu-David Lerner, z”l |

| Lubling (Zusevich), Chana | In Memory of her parents: Chaya and Leib Zusevich, z”l |

| Likhovtsky, Aharon | In Memory of his parents: Roza and Aryeh Likhovtsky, z”l |

| Nusimovich, Zeev | In Memory of his parents: Sara and Moshe Nusimovich, z”l |

| Nusimovich, Jean and Olya | In Memory of his and Olya's parents: Tsila and Lyova Shwartz, z”l |

| Spectorman (Kharlamb), Dina | In Memory of her parents: Klara and Yosef Kharlamb, z”l |

| Porat, Khary | In Memory of his mother: Roza Porat, daughter of Abraham Strakhilevich, z”l |

| Konstantinovsky, Lionya | In Memory of his parents: Olya and Aron Konstantinovsky, z”l |

| Kornblit (Lerner), Manya | In Memory of her parents: Rivka and Yeshayahu-David Lerner, z”l |

| Roitman, Mordechai | In Memory of his parents: Chana and Yosef Roitman, z”l |

| Rotenberg (Katz), Etya, Canada | In Memory of her parents: Chana and Israel Katz, z”l |

| Shwartsman, David | In Memory of his parents: Malka Riva and Baruch Shwartsman, z”l |

| Shwartsman, Ester and Yacov | In Memory of her parents: Malka Riva and Baruch Shwartsman, z”l |

| Yudkovich, Shalom | In Memory of his parents: Gitya and Yekhiel and sisters Batya and Sara, sister, Rachel Kolpetsky Yudkovich and her son Noah, z”l |

| Zusevich, Shaya | In Memory of his parents: Chaya and Leib (Liv) Zusevich, z”l |

| Dr. Moskovich-Zusevich, Ella | In Memory of her parents: Solva and Asher Zusevich, z”l |

[Page 8]

Members of the Committee*, Veteran Citizens**, New Immigrants***

|

|

| From left to right: First Row: Markuzan, Mozya,*** Yanover, Misha,*** Spectorman-Kharlamb, Dina** Second Row: Cohen-Katz, Tova,** Weinshtein, Polya,* Markuzan-Katz, Nadya,*** Tsalis, Manya,*** Chichilnitsky, Manya,** Tsalis, Pinya,*** Yatsiv, Yehuda* Third Row: Zusevich, Chana,* Shwartsman, David,* Committee treasurer Konstantinovsky, Lionya,* Secretary and Editor of the Yizkor Book Kogan, Josefina,* Basis, Tanya and Misha,*** Porat, Harry* Russian text:

Row 1: Markuzan, Mozya; Yanover, Misha; Kharlamb, Dina Row 2: Katz, Taba; Weinshtein, Polya; Markuzan-Katz, Nadya; Tsalis, Manya; Chichilnitsky, Manya; Tsalis, Pinya; Yatsiv, Yehuda Row 3: Zusevich, Khana; Shwartsman, Dudya; Konstantinovsky, Lionya; Kogan, Zhozya; Basis, Tanya and Misha; Porat, Harry |

[Page 9]

Hebrew text:

The Jewish Community of Chilia Nouă (New Kiliya) received official status in 1927. The leaders of the Community were Pinkhas Kitsis, Hirsh Gamshievich and Dr. Naum Rabinovich. The head of the Burial Society was Nakhum Davidovich. At the beginning, the community activities were very limited. After 1934, the community received a new status according to the Law of Religions, and thus began a new development. The leaders of the community were: Rafael Safris, chairman, Mordechai Gertsovich and Pinkhas Weisman, vice chairmen, Yosef Katz, treasurer, and Rafael Davidovich, secretary. The council had 25 members, including the leaders. At this time, all public institutions in town that functioned on their own or without elected leaders were transferred to the elected committee.

The severe famine that occurred in Southern Bessarabia in 1935–36, presented a very difficult task for the community, which had to help about 200 families for many months. Even if there was some help from outside, the community carried most of the burden.

Kiliya - Entry from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia 1963 in Russian. Kiliya – Entry from Encyclopedia Judaica, Jerusalem 1972 in English.

Russian text:

KILIYA is a city in the center of the Kiliya region of the Izmailskaya oblast of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. It is a port on the Kiliya branch of the Danube River, 45 km below Izmail and 40 km from the Black Sea. Kiliya has a ship-repairing factory, food industry businesses (including canning and wine-making), and construction material production. Fishing; a fishing kolkhoz has been established. There are (in 1953) 14 general education schools, nautical and cotton production mechanics schools, a vocational institution, House of Culture, 7 clubs, 3 libraries, and 2 movie theaters. In the region, on the fertile lands of the Danube flood plain and on the islands, there are civilizations based on grains/beans, citrus, vegetable/squash, and technical cultures, as well as grape growing (winery). An incubator-poultry station. Three machinery and tractor stations and a machine land improvement station.

“GREAT SOVIET ENCYCLOPEDIA”

1963

Hebrew text:

| Khotin | 9,227 | 50.2 | 48.3 | 45.5 | 40.2 |

| Soroka | 8,783 | 57.2 | 76.4 | 112.4 | 183.7 |

| Beltsi | 10,348 | 56.0 | 38.7 | 231.2 | 128.6 |

| Orkhei | 7,144 | 57.9 | 72.1 | 130.3 | 186.5 |

| Bender | 10,644 | 33.5 | 28.2 | 151.4 | 109.4 |

| Akerman | 5,613 | 19.9 | 12.1 | 132.2 | 41.7 |

| Ismail | 2,781 | 9.7 | 12.8 | ? | ? |

| Bolgrad | 1,196 | 9.7 | ? | ? | ? |

| Kiliya | 2,152 | 18.5 | ? | ? | ? |

| Note on the Jewish population of Kiliya

In the Romanian Census of 1939, the number of Jews was estimated at 1,969. The Russian census in 1897 shows 2,152 (shown in this table). Our real estimate is that in 1940, there were 2,400 Jews in Kiliya. This is based on the list kept by the committee for the distribution of matzot (where my father, z”l, was a member). L.K. |

[Page 10]

|

|

Kiliya, by Nikolai Andreevich Kunitsa, Printed in Odessa 1962, 142 pages. |

This is the only known book about Kiliya.

Excerpts from Kunitsa's book.

Russian text:

N. Kunitsa

KILIYA

KILIYA is a very old town. Its streets and squares have seen the ancient Greeks and the iron military formations of Alexander the Great, the cohorts of the Roman emperor Trajan and the regiments of Russian Princes Igor and Sviatoslav, the fierce Turk and Mongol conquerors and the ferocious Janissaries, the legendary Zaporozhian Cossacks and the troops led by Suvorov and Kutuzov, steeped in glory.

A passenger boat navigates along the Danube and approaches the port. There are hoisting arms, a granite embankment, and flowers. Beyond that is the city of Kiliya – just as beautiful as its name. It starts right at the port gates. Blocks of white homes, straight streets, an old shaded park above the lake, monuments, squares, and then new factories with white-stoned workshops and vineyards planted nearby. Kiliya stretches for 12 kilometers along the Danube River.

The history of Kiliya goes back into the distant past.

Likostomon. That is what the ancient Greeks called the trading colony at the mouth of the Danube that they founded in the 7th century BC.

It is possible that the Getae tore down Achilia, established by Alexander the Great, along with its church.

In the middle of the first century AD, new conquerers appeared at the mouth of the Danube. Again, dust covered the Kiliyan ground.

Why did the Roman legions fight so fiercely here, far from their homeland? Emperor Trajan's wall, built by slave laborers, speaks eloquently to that. The tall eight-meter wall extends from the Prut River in the southeast to Lake Sasyk.

Hebrew text:

KILIYA is a very old town. Greeks and Romans passed through its streets and squares. The armies of Alexander the Great, the armies of the Roman emperor Trajan, the Russian armies of Princes Igor and Sviatoslav, Mongols, Turks, Cossacks, and troops led by Suvorov and Kutuzov also passed through.

The passenger boat that navigates on the Danube approaches the port. The shore is paved with granite stones, and there are lots of flowers. Kiliya starts right at the port gates. The city is beautiful; it has straight streets and large intersections, white houses, a shaded park, monuments, cemeteries, and factories built in white stone. Vineyards spread right where the factory district ends. Kiliya stretches for 12 kilometers along the Danube River.

The history of Kiliya goes back into past centuries. It was an Old Greek city-colony named Likostomon (Wolf Jaws) founded in the 7th century BC. Alexander Macedon named it Achilia. In the middle of the first century AD, the Roman conquerors turned Kiliya into dust. The Romans fought here fiercely. In order to better defend the city, the emperor Trajan built, with slave laborers, an eight-meter wall that runs from the river to Lake Sasyk (near Kiliya). It was destroyed by the Greuthungis, a Gothic people of the Black Sea steppes in the third and fourth centuries.

[Page 11]

Russian text:

In the 4th–6th century AD, the Slavs settled in the Danube delta. History itself chose them to be the conquerors of this land full of troubles. It sent a master here in the form of the Slavs – a worthy master that could hold its own.

And the Slavs fulfilled their great mission for history. For the last 1500 years, they have remained in this native territory.

Kiliya gradually became a formidable fortress of ancient Russia. And since that time it has been remembered in history as “the fortress Kiliya on the Danube.”

An old church, St. Nicolas, built in the 11th–12th centuries and now declared an architectural monument, is still standing a few blocks from the port.

The church has an interesting history. When the Mongols invaded, the church was destroyed but was rebuilt in the 17th century by a Moldavian prince, and in the 19th century by the Russian government. During the Turkish occupation, it was converted into a mosque, and a high wall was erected around it.

After the Tatar invaders were defeated, Kiliya was annexed to the principality of Moldavia. During those years, Kiliya gained another name – Vazia, as the Genoan merchants called her.

Kiliya became one of the most prominent cities and ports of the Moldavian nation. Trading flourished once again. In addition, handicrafts, literature, architecture, and art developed.

There is a legend from before our time about two young and courageous girls from Kiliya, Katenka and Mashenka. They preferred death to Turkish captivity and threw themselves into the Danube from a janissary's boat. In memory of the young patriots, two islands in the Danube are named Mashenka and Katenka.

When the area was liberated from the Turks in 1812, including Kiliya, it started to develop rapidly. In 1827, the population of Kiliya was 3,671. Kiliya was considered a town at that time. Its population primarily consisted of Russians, Ukrainians, Moldavians, and Jews.

|

|

| An old cannon used by Kiliyans to shoot the traditional salute in honor of the Russian Army |

|

|

| An old banner of Kiliya |

Hebrew text:

In the 4th–5th century AD, the Slavs settled in the Danube Delta. History itself chose them to be the conquerors of this land full of troubles, and for the last 1500 years, they remained the inhabitants and defenders of this territory.

Kiliya became a fortress of ancient Russia. An old church, St. Nicolas, built in the 11th or 12th century, is still standing not far from the port. When the Mongols invaded, the church was destroyed but was rebuilt in the 17th century by a Moldavian prince. During the Turkish occupation, it became a mosque, and a wall was erected around it. After the Tatars invaders were defeated, Kiliya was annexed to the principality of Moldavia. The Genoa merchants named her Vazia. Kiliya became a large port city where commerce, manufacturing, architecture, and culture flourished.

There is a legend about two young and courageous girls from Kiliya, Katenka and Mashenka. The Turks took them prisoners, but they chose freedom by jumping into the Danube instead of being Turkish slaves. Unfortunately, they drowned in the river. Two islands were named in their memory.

When the area was liberated from the Turks in 1812, Kiliya started to develop rapidly. In 1827, the population of Kiliya was 3,671, a mixture of Russians, Ukrainians, Moldavians, and Jews. Kiliya was considered a town at that time.

[Page 12]

Russian text:

It was June 30, 1901. The workers in the flour mills, outraged by ruthless exploitation and penalties, unified themselves and announced a strike. The workers stood their ground firmly.

In March 1917, the Kiliyan Soviet Committee was established, consisting of workers and soldiers, but the leadership was assumed by Mensheviks, Socialist Revolutionaries, Liberals, Ukrainian middle-class nationalists, and anarchists.

The meetings were held from morning to evening in a city club (present-day 47 Lenin Street) where the Soviet Committee was located.

In the second half of December 1917, a new revolutionary order was established in Kiliya. The Revolutionary Committee, led by Ignat Soloviov, was created in the city. All authority was transferred to the Revolutionary Committee. It confiscated the house of Giles, a rich landowner, and forced port and sawmill workers to join the Red Guard.

The arrival of boyar Romania into Bessarabia and the Danube area was marked with mass shootings, robberies, and arrests of peaceful civilians from the first days. Soviet councils, land committees, and all other representative bodies of the people were dismantled by the Romanian occupiers, and the members were shot.

In September 1924, a large revolt led by Andrey Kluzhnikov took place in Tatarbunary. This revolt marked a courageous page in the fight for the liberation of Bessarabia.

Also in 1924, in the marshland area between Kiliya and Vilkovo, a rebel partisan group waged their heroic fight under the leadership of the courageous sailor known as Terenti.

In the spring of 1933, the Secret Police of Romania (Siguranţa) in Kiliya trailed and arrested a number of members of the underground organization, among them Dimitri Soloviov, but new patriots came forward to replace the fighters. The underground movement continued the fight.

In 1934, a large number of workers and intellectuals joined the underground Communists, and it grew into a major party organization.

On June 28, 1940, at 2:00 PM, the Soviet Army, following the command of their government and people, crossed the Dniester River and began their liberating march.

The Romanian occupiers, seizing the moment, decided to to loot the city of Kiliya, taking goods with them by boat. The people fought hand-to-hand on the city streets with the gendarmerie and the police.

From the first hours, this fight was led by the Communist organization, emerging from the underground, under the leadership of K. Pivovarov, I. Rulyakov, and D. Soloviov, who was just returning from prison. Having united with the large group of intellectuals headed by Dr. N. Rabinovich, they worked together to organize workers into fighting regiments.

During the years of Romanian occupation in Kiliya, more than ten new public houses and taverns were built, besides the villas of wealthy landowners. A small electrical station was also built to light up the houses of the rich in the city center. Running water and bathrooms did not exist. Water was brought from the Danube in barrels and delivered to the population at a high price.

Hebrew text:

In 1903, the workers of the flour mills organized a strike to demand better pay and working conditions.

In March 1917, the Kiliyans established a Soviet Committee consisting of workers and soldiers. The committee was ruled by Mensheviks, Liberals, anarchists, and townspeople. The meetings were held in a club on Bolshaya Dunayvskaya Street (now Lenin) at number 47.

In the middle of December 1917, a new revolutionary order was established in Kiliya. The Revolutionary Committee, led by Ignat Soloviov, installed Soviet power, confiscated the house of Giles, a rich landowner, and forced the workers to join the Red Guard. Romania annexed Bessarabia and the Danube area in 1918. They dismantled all Soviet administrative institutions, arrested and executed the leaders and a large number of the inhabitants.

In 1924, a large revolt led by Andrey Kluzhnikov took place in Tatarbunary. This revolt marked a courageous page in the fight for the liberation of Bessarabia. In the marshland area between Kiliya and Vilkovo, rebel partisan groups, led by the courageous Terenti, fought against the Romanians.

In 1933, the Secret Police of Romania (Siguranţa) in Kiliya arrested a number of rebels, among them Dimitri Soloviov, but the underground movement continued to fight against the Romanians. In 1934, a large number of workers and intellectuals joined the underground Communist organization.

On June 28, 1940, at 2:00 PM, the Soviet Army crossed the Dniester River. The retreating Romanians took advantage of this event and started to loot the city, taking with them cars full of goods. The people fought on the city streets with the gendarmerie and the police. The underground Communists, lead by K(haim) Pivovarov, I. Rulyakov and D. Soloviov, and the intellectuals group of Dr. N. Rabinovich organized workers in fighting regiments.

During the Romanian occupations, the landowners built many villas, and a small electrical station to light up the rich houses in the city center. Running water and bathrooms did not exist. Water was brought from the Danube in barrels, and the water carriers (vodovoz) sold it to the population.

[Page 13]

Russian text:

On June 22, 1941, at 4:00 in the morning, the pre-dawn quiet of the sleeping Kiliya was exploded by artillery. The ammunition and mortar shells destroyed the port and the nearby city streets with deafening crashes. The Romanian and German artillery opened enemy fire from the area of Old Kiliya across the river. On the very first day of the war, hundreds of Kiliyan patriots voluntarily joined the army and stood to defend the city with weapons in hand.

Soviet people heroically defended the Danube delta, but the enemy was strong at the beginning of the war. On July 9, under the onslaught of the dominating powers of the Fascist troops, our troops were ordered to retreat from the area of Old Kiliya. During the night of July 18–19, after a series of fierce battles, the Soviet Army retreated from Kiliya.

With the arrival of the German Fascists and the Romanians in the city, widespread torture and executions began.[2]

On August 20, 1944, the Soviet Army of the Third Front of Ukraine dealt a crushing blow to the Germans and Romanian invaders south of Bender and, jointly with portions of the army of the Second Front of Ukraine, entered the expanse of the Bessarabian steppes. The German and Romanian troops, located in southern Bessarabia, retreated through Kiliya and nearby Vilkovo, trying to cross the Danube.

“The ship led by Senior Lieutenant Vorobiev was the first to arrive in the Kiliya port,” said G. Krivchenko, a participant in the fight for the city's freedom, “and start a landing attack. Dedicated to his sailors, Senior Lieutenant Kogan jumped overboard. In a short but ferocious fight, the forces drove the Nazis out of the port and the city park.”

These unforgettable, terrible years of war, as well as the heroic acts of the Soviet people, will stay in the citizens' memories forever.

In the green parks and squares of Kiliya, Vilkovo, Desantny, Primorsky, and Furmanovka, there are many monuments and markers to commemorate the courage of the heroes who fell in battle to the German and Romanian invaders during the Great War and to the patriots who were killed by the Fascists.[3]

|

|

| Monument to the Heroes of the Great Patriot War |

|

|

| Club of the shipyard workers |

Hebrew text:

On June 22, 1941, at 4:00 in the morning, the Romanians and their German allies attacked and bombed Kiliya by artillery fire. The primary targets were the port and the city streets. Many people from Kiliya joined the army to defend the city, but the defense was not successful, and on July 9, the Soviet troops were forced to retreat from the area of Old Kiliya. On 18–19 of July, as a result of heavy fighting, the Soviet Army retreated from Kiliya. The German Fascists and the Romanians occupied the city and immediately started to torture and execute the population.[2]

On August 20, 1944, the Soviet Army of the Third Front of Ukraine crushed the Germans and Romanians near Bender and, jointly with the army of the Second Front of Ukraine, started freeing up the Bessarabian territory.

The enemy forces retreated through Kiliya and nearby Vilkovo, trying to cross the Danube. First, Soviet marines arrived in the Kiliya port on the ship led by Senior Lieutenant Vorobiev, and the First Unit, led by Senior Lieutenant Kogan, conducted a short but victorious fight with the German soldiers in the port and in the park...

This war will not be forgotten, and the courage of the Soviet people will be remembered forever.

In the parks of Kiliya, Vilkovo, Furmenka, etc., there are many monuments to remember the courage of the heroes who sacrificed their lives in the fights with the German and Romanian Fascists during the Great War and to the patriots who were killed by the Fascists.[3]

[Page 14]

Russian text:

Today and Tomorrow

During the entire time of its existence, Kiliya has never known such major development. In today's Kiliya and the surrounding area, there are new constructions, dams, channels, flood plain and irrigation development, and huge new reservoirs. People are reshaping the map of the city and region.

On the main street we have the head party and Soviet agencies – the district committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, the City Executive Committee, and the District Executive Committee, as well as the Pioneers House, a children's library, and a vocational school. The main street extends a long way. It leads to the outskirts, to the beautiful stone administration building for the “Way of Lenin” kolkhoz – one of the wealthiest properties of the region. But more on that later.

And now we turn right, going along Lieutenant Kichenko Street with its blocks of new homes, and we will go onto another one of the city's main roads: Gagarin Street.

The city is very beautiful. All the roads are paved and surrounded with greenery, and comfortable public buses run their routes. There are many new squares and parks. The city is decorated with new buildings for the Kiliya-Dzinelor line railroad station and the seaport.

|

|

| Kiliya – Mezhkolkhozny Channel |

|

|

|||

| Kiliya fishing spot. Marya Timofeenko, a Kiliyan master fisherman |

Lenin Street |

Hebrew text:

Now Kiliya is undergoing a great development. There is new construction everywhere, manufacture and irrigation development, new housing, canals, bridges and all kinds of infrastructure that are improving the daily life. In the town center there are administration buildings, the Pioneers house, a library, a vocational school, etc. The city is beautiful, all roads were paved, a new railroad station was built, and there is public transportation.[4]

Notes of the Hebrew translator:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kiliya, Ukraine

Kiliya, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 1 Jan 2023 by LA