|

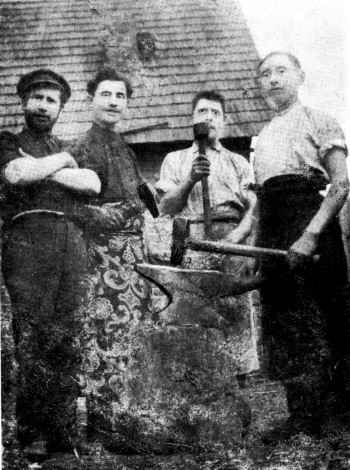

Moshe Ritz (Moshe Feiga–Leah's), Yisrael Pagir, Tevka, Shlomo (son of David Elia the coachman)

|

|

[Page 297]

[Page 298]

|

|

| Smiths (1911)

Moshe Ritz (Moshe Feiga–Leah's), Yisrael Pagir, Tevka, Shlomo (son of David Elia the coachman) |

[Page 299]

by Yisrael Yaakov Pagir

Woe, woe, roll the blacksmith

Roll does he well

His stall and metal limbs

Set the blood on fire

(From the Iliad)

My father, who knew some Torah and worshipped three times a day, understood the prayers. He would sit at the table between Mincha and Maariv in the Karebelgikshen Kloiz on Breizer Street, and listen to the rabbi's sermons. He earned his livelihood as a tailor, not as successful as Naftali the tailor and his son, from among our Jewish brethren – but for the gentile acquaintances from the surrounding villages, he was a very good tailor, for he did not charge too much for the pieces of fur that the gentile brought for a fur coat. If the fur coat turned out long or wide, then father was the best craftsman. My mother was an exquisitely beautiful woman, always with a nice kerchief covering her beautiful curly head of black hair. Hardened and tired, she would bring bread home for the nine children, one more beautiful than the other. She knew how to pray and recite the petitions[1] – which was a great wonder. Yose the tailor did not want his wife to go to worship at the kloiz, and stand next to the zogerke[2] and help her with her groaning. He did not allow her to go to the kloiz, where she would not know how to worship from her own siddur [prayer book]. He taught her and I always wondered.

My Father and his Customs

When he would come home from the kloiz, he would tell all the news that he heard, as well as what he had learned at the table. We children were amazed at Father who knew about everything. Once when somebody asked him to remove a half of a strip of fur from a fur coat, he said to Mother with a sigh and a groan: “You know? Three types of Jews do not get the World To Come: Rabbis, who live off the accounts of others; shopkeepers, who use false weights and measures; and tailors, who steal the remnants and sell them to others – and the gentile[3] immediately asks, 'If it is not allowed, why do you steal?'”

“I do not steal for myself. I steal for perhaps a pair of winter boots for you… For bread, I earn, but for boots I must steal, and lose my World To Come… (A tailor's accounting, from my father's treasury). Feiga, what would you say if you had no money? Look at your five sons, each one of them is worth as if a treasure from a thief, a dowry of 300 rubles. Do you have no less than 1,500 rubles? We also have four daughters, such beautiful daughters with a sparkle in their eyes, they would be grabbed up from you, with a kiss on the hand, for 150 rubles cash and a 150 promissory note. We would only require 500 rubles. Subtract the 500 rubles from the 1500 rubles, and you will be left with 900 rubles. Show me one wealthy man on Breizer Street who has ready cash?”

My father was very concerned to find trades for his five sons, from which they could earn livelihoods, and would not be at different

[Page 300]

stations of life from each other and have jealousy and hatred. He set up my eldest brother with our neighbor, Archik the rope maker. With regard to me, on account of my learning and writing, he felt I would be suitable as a rabbi. What about the third one? He would be a tailor. The fourth one, who eats bread like an athlete, would be a shoemaker. The fifth one would be a clockmaker or a smith.

“What do you say Feiga? Do you like my plan?” My mother said, “They should grow up in good health. We will then see.”

The Fire and the Beginning of My War

It was a miracle from heaven – our house was spared from the flames. Was this due to the merit of Shimon the teacher? Or perhaps due to the merit of wet blankets on the roof, that Father had moistened with cold water that the five boys had fetched. Or perhaps in the merit of the wind that blew toward the Viliya. Father's wealth remained with a roof over the head. When the sun shone, it was a roof, and when it was raining, it was a sieve; however, as long as it did not rain, it was not so bad. It would have been worse, Heaven forbid, if the house had burnt down. The intelligent fire victims who lived as neighbors, who did not lose anything, had clear thinking, and if the flames were to affect them, they would find a place in the Talmud Torah. Each family took over one corner. The children whose rooms had not burned down were the most unfortunate. To their dismay, they had to go to cheder. However, the over 100 children who went to the Talmud Torah either remained free as a bird or became workers, earning ten kopecks a day fetching bricks. I also started to work at transporting the bricks from one place to another. It did not take long for the skin of my finger to become worn down. I escaped to my home and left behind my work. Father bandaged my finger.

“If you were looking for the reason for the work, listen to me, “Father said to me, “We do not know when the Talmud Torah will open. In the meantime, go to the Yeshiva or the Beis Midrash and study Gemara. You will indeed become a rabbi.”

I immediately responded that I did not wish to become a rabbi.

“So, working is better? Look at your finger. You still have a few years until your Bar Mitzvah. Even if you will be a poor tailor, some Gemara will not hurt.”

I went to the Beis Midrash, mourning and distraught. I went to the table where the children were studying with the rabbi. One was shouting louder than the other.

“What do you want to say, son?”

“Father sent me to study Gemara.”

“What have you studied until now?

“I studied in the Talmud Torah.”

“With gentiles?”

“No, with Jews,” I answered in anger, even though he was a teacher. He did understand, though, that he should not ask any more. He tested me in Bible. He realized that I knew Bible well. He opened up a Gemara, and said, “Show what you know?” I read the Gemara with understanding, but without the Gemara melody. The children laughed, but the rabbi said that I was a good vessel that one must fill with Gemara. I

[Page 301]

sat down at the greasy table and pined for my teacher Yachnovitz who moved away after the fire. I wanted to complete the lesson, so I reviewed the Gemara without spirit and without feeling. I studied in the Yeshiva until my Bar Mitzvah. The day after My Bar Mitzvah, I no longer wanted go to the Yeshiva. My father stated, “We do not abandon things in the middle. It is only a few months until Rosh Hashanah. The old year will end. When the new year comes, on the intermediate days of Sukkot we will think it through and discuss what next.” There was nothing I could do, one must obey Father. On the intermediate days of Sukkot, the directors of the Yeshiva, Yankel the vinegar maker and Shalom Keidainer claimed to my father, “A boy who knows how to learn must learn.” They discussed my situation – if I would study in the Beis Midrash under the supervision of the Vilkomirer Parush during the winter, I could go to the Slabodka yeshiva in the summer. Then Father asked me, “What do you say?” I responded briefly and sharply:

“I do not want either Slabodka or the Beis Midrash. If you send me to study worldly subjects, I would go to the ends of the world and do everything. If you would permit me, I would study a trade. If I must go to the Beis Midrash to study, which I do not want to do, I will escape at the first opportunity.”

My Father's Plans

This is what I promised. Good or bad, the winter passed. When the summer came and the gentiles had no time to bring work, Father had no work. He decided that after the Sabbath he would walk to a village that he was familiar with to seek a bit of work. I waited for this. On Sunday morning, Father set out for the village. Instead of going to the Beis Midrash, I set out to seek work, and I found work: helping a turner move the runner by foot, polishing wooden oak legs of a table or furniture. I earned a zloty a day, and worked for the week. Father returned on Friday afternoon, and Mother did not tell him. On Sunday morning in the kloiz, he found out that his darling had left the Yeshiva. Father went to the turner, and summoned me home. Father gave me a lecture – what kind of a thief was I from him, I am throwing a way a life of honor, for I was destined to receive rabbinic ordination.

“A wealthy Jew would come to the Yeshiva, who would want to marry off his daughter and would want a son–in–law who was a rabbi. You would receive 100 rubles as a dowry, and a several years of support, and you would live a life of good fortune. And you want to throw everything away and become a tailor, a tradesman. You want to be a poor man like me?”

When my father concluded his lecture, I responded:

“I recall that you have said that a rabbi does not get the World To Come, and a shopkeeper is a thief, and now you want me to become a rabbi, and to be the son–in–law of a wealthy shopkeeper and be supported from stolen goods, from dishonest weights and measures? I am certain that a wealthy householder who has a thousand rubles for a dowry could find better sons–in–law than poor lads, unless the bride is so ugly that one cannot look at her, or if she has a blemish on her eye.”

I Become a Tailor

My mother began to laugh at my lecture. Father became angry:

“You want to become a tailor? I will not teach you. I will not teach a lad who is able to write and study, and become party to such a crime. Go to Leizer the

[Page 302]

tailor. When I was a lad, I worked for him. Tell him that you are my darling, and that you want to become a tailor.

I won the first battle, and, as an arrow shot from a bow, I hurried to Leizer. He asked me to sit down. He gave me a thimble, as well as a needle with a bit of cloth and a thread, so that I could learn how to hold a needle in my hand. I worked with Leizer the tailor until the intermediate days of Sukkot. I was not happy to work with him, and I was not able to get accustomed to the tailoring witticisms.

In Pilvinski's Shop

As Father requested, from that day and onward I had to pay something toward shoes and clothing, and Leizer refused to pay. Father told me to seek another type of job. I was happy, and I accepted a position with the shopkeeper Pilvinski. His shop was across the way from the Polish church, along the way to the barracks, right where the Russian girls and boys used to come in the winter to stroll and choose brides or grooms.

I did not work that hard, but it was enjoyable. I enjoyed very much when, on the long winter evenings, Leib Granewitz, the tall lawyer Alter, and others would come in with the Hatzefira newspaper, and we would have full debates about Jewish problems and the anti–Semitism of the Russian regime. I would sit and listen in a corner, so that they would not see me. Pilvinski did not look for any work for me. I had great enjoyment as I learned more things about the world, more than I did in the Beis Midrash, and furthermore, I earned a ruble a week in salary. Granewitz and Yankel were Zionists, and they wanted Pilvinski to purchase a shekel[4], but he was stingy. Aside from them, sometimes Melechke the hunchback would come in with two others to request money for the Bund. Pilvinski would give them 15 kopecks. They wanted Pilvinski to register his name, but he refused this honor. Melechke the hunchback signed. A bit later, youths from important Jewish families would come in to request money for the S.S. Pilvinski gave them nothing and almost chased them out. His wife asked:

“Does it make sense? You give 15 kopecks to someone who you do not know? To the youths – and I know them all – you give nothing?”

“The other I do not know. I am afraid of him. These ones I know. They are fine children, and they will not do anything to me.”

My first year of working passed for better or for worse, but I felt as if I was a free person. On the intermediate days of Sukkot, I spoke to the boss. I had worked well for him, and I asked for a raise in salary. He understood that I was correct, and he was very happy with me; however, he could hire a Bar Mitzvah boy for a ruble a week for the work that he required. I was now a very shamed youth, and I had to go to seek work. My father completely refused to get involved with my work situation.

“You do not want to obey. Do as you wish.”

[Page 303]

I had an idea: to go to Avchik Pagirsky in his metal business and ask for work. I would go to ask before I went to eat lunch at home, so if I was fortunate, I could announce the good news at home. As I passed by Hane Matel's three story brick house and took a look, my breath was taken away. I read the sign with large Russian words, and my heart pounded like a hammer. Crossing the street, near Lazer Levi Itzik's I cast a glance to see if Pilvinski's customers were there. I took a deep breath, and went by the street with hasty steps, went up the three steps in one breath, and entered the dwelling and stood at the door. Something glared in my eyes: the gold and silver samovars sparkled on the opposite shelf like mirrors. People were all around. Gentiles collected cash boxes. They shook and put the boxes near their ears to hear the clanging. I reviewed what I was preparing to say. When Sherl Pagirsky asked, “What do you want, lad?” I do not know what I answered… I answered the other questions as follows:

“Where did you work? Can you write?” I responded that I could read and write Yiddish and Russian, and could do arithmetic.

“Where did you study?”

“In the Talmud Torah.”

“Do you want to work tomorrow? What is your name?”

“Yisraelke.”

“You are already a big lad, we will call you Yisrael. If you work for a few weeks, I will tell you what I will pay you. Do you want the money every week?”

“I do not need money. My mother requires that she can come to request it when she needs it.”

“You are a good boy toward your mother: Come, I will show you. When you come tomorrow, you will go to Avraham, and work with him.”

I exited, going through the iron doors to the yard: iron, iron, iron and steel in the paved yard. Near the windows there was iron. It was a world of iron.

“This lad will help you. His name is Yisrael.”

I looked at Avraham and wondered who called him Avraham? Just as they named me Yisrael, Avrahamele would have fit him better, a minute little thing. After that I found his appropriate name, Avrahamele the Little Pepper. I did not walk home, but ran. I opened the door and said that I was an apprentice with Avchik Pagirsky in his iron workshop. What should I say? I said it over and over again. During the week, my lunch was farfel stew with sour cream, blueberries and white sour cream. Father helped Mother make the meal for me… I still recall the taste today. I left in the morning as Yisraelke and came back at noon as Yisrael, and my father remembered well what had to be done. My employment at Avchik Pagirsky's iron workshop was an honor. Aside from earning my salary of two rubles a week, I felt as if I was living in the Garden of Eden. Furthermore, at home, my younger brothers and sisters looked upon me with awe, and even my father said that it worked out for the best.

Working in the yard with Avrahamele and Kachel Zaflatz the cart man was enough to laugh. In the evening, when the brouhaha with the customers of the day ended, and we

[Page 304]

were involved with filling the orders or the requests that came by mail and packing them up to send them to the metal merchants in the surrounding cities, they called me to go with the older people to remove the tools and iron products from their tall shoulders. I especially liked doing this for Freidele due to her refined mannerisms and her beauty. Everyone had the same opinion. I do not follow the Jewish custom of not stating a person's praise in front of him. I do not say – I write, and when I write, I believe it is permitted by all opinions.

As I am dwelling on the memorials from that period, it is appropriate to mention Ronka Das and Shulka, as well as Alter Miche's, the fine person and wagon driver, as well as Michel Kapusta, his wife, and their horse. There were to some extent examples of those whom the Yanover Jews in that trade were jealous of, for they also were involved in working with Avchik Pagirsky. Then, something took place that turned my life in the direction of a completely happy life.

I Prepare for a Higher Level

Then a day came when Avrahamele the Pepper committed a wrongdoing. I am not completely sure about what happened, or whether it was only a mishap. Mende Tzemach's arrived with a gentile to purchase some iron for a wheel. His order was estimated at ten pounds extra, and the gentile unfortunately paid. Forty extra kopecks were taken, and Avrahamele and Mende divided the stolen money at 20 kopecks a person. I noticed that a gentile already paid for the iron and placed it in his wagon. When Sherl Pagirsky noticed that Mende was with the gentile, she asked him to carry the iron back and lay it on the scale. It was ten pounds less than what the gentile had paid for. Sherl returned the 40 kopecks. She told him that they had tricked him. She told Mende that he must no longer come with customers to trick them, and to Avraham she said, “You must not do this anymore, for you will have a bad end.”

One fine day, whatever the reasons were, the goodhearted Sherl Pagirsky expelled Avraham from the yard, and even closed the door behind him herself and said:

“You shall never set foot in this yard again.” To me she started to say:

“You can come without him. You do not need him. Karel will help you. I feel a great pain, but I felt I had to issue the punishment for dishonesty.” The preparation for a higher role was a great thing for me. The improvement could be seen in that when written orders arrived, nobody had to stand with me to check and adjust the weights. I did everything. The fact that I could read and write Yiddish, Russian, and even Hebrew also came in handy, for many metal shopkeepers used a Hebraic style in writing their orders. Hebrew letters used to even be written by the metal shopkeepers, and Moshe Mishelevitz knew the language well.

The summer passed, and Avraham used to go to work at floating the barges on the Viliya and even on the Neman. However, it got cold after Sukkot, and Avraham was no great hero. Avraham and Bayla were in great need, and several of their children helped.

[Page 305]

Sherl Bluma's gave a raise of a half ruble a week for each child, and according to the calculations, there were already seven. When Avraham got married to Bayla, he was earning three rubles a week, and when he lost his job, he was earning 6.5 rubles a week. This was the calculation.

When I came to the yard one Sunday morning during the month of Cheshvan, Avraham was already there, dressed in his work clothes. He was standing and crying, and also…

Finally I Decide to Become a Smith

I felt the tragedy of not having work in my hand. I realized for myself that I had no way other than to study to become a smith. A carpenter who makes furniture earns well. A smith also earns well, due to the fact that Pagirsky takes in all the goods that smiths produce, purchases them, and sends them to all the cities. I knew that Moshe Feiga Leah's and Mota the Smith, Hirsh the son–in–law of Ben–Zion were seeking a worker. I immediately set out to find out who would be prepared to teach me the work. Yisrael became a smith, and then he was back to Yisraelke. I understood that this was a major step, and I assured myself by making a condition: 100 rubles a year with food. I was certain that eating at home would not happen, and I would even be sleeping in the smithy. It was my desire and aim to become independent, and to earn my living through honest work.

My father felt that the sky was falling in Breizer Street. Such an honorable job I was throwing away, and I was throwing away the learning and writing into the mud! Why would a smith need to study and write? My father did not speak to me for a few months. On account of a battle with a competitor, I had to leave my position. I began working with Moshe Ritz. Since Moshe Ritz was a sick man, I was the full–fledged second in command. We sent all types of hinges to Vilna. I worked and was the manager with six helpers. I wrote the letters, the addresses, and the accounts. I worked until 8:00 p.m., and then conducted the correspondence in my house.

As an 18 year old, I was already earning seven rubles a week. My father made a request of me when my sister was about to get married, and I had to give a contribution of 100 rubles. I gave my mother three rubles a week, kept one ruble for myself, one ruble was put in the bank for me by my boss – or two rubles a week when I earned more.

I Follow the Tide to America

When all the young lads started to go to America, Moshe Ritz took me on as a partner, with 40% for me and 60% for him. I was not going to go to America, because for me, America was here. Unexpectedly, on a Thursday night in the month of February, Yidl the mailman brought me a ship ticket to America. I went to the eye doctor in Kovno on Friday morning. On Saturday, I visited my acquaintances, and on Sunday morning, I set out on the trip. I snuck across the border. On March 1, 1913, we I arrived at Ellis Island near New York on the Fatherland Ship. I arrived in the city of Pittsburg as a 19 year old on March 4, 2013

[Page 306]

as they were swearing in President Woodrow Wilson.

I tinkered around for a week, and then realized that I must begin to think about work, if I wished to get work in a smithy. How would a Jew come to a smith? A gentile is a smith. A Jew is either a peddler or a tailor. I did not want to hear about such things. The work that I was interested in must lead me to self–sufficiency. That was what I wanted. One cannot get rich from working, and there was no hope to move up from work – so my cousin told me.

My cousin found an announcement in the newspaper that someone was looking for smiths in a place where they made locomotives for the railway. I was happy. In the morning, I went on the tram with my cousin as my guide and interpreter. We arrived at the factory, and they directed us to the blacksmith's shop – as it was called in America. They opened the door for us, and we entered hell: fiery flames, clanging hammers, the smiths – gigantically tall, large, hefty men, and I looked like a child next to them. The foreman explained to us courteously that here, they must have people who understand the language, and they must be able to know the signals since one does not hear what is spoken. He told me to come back when I understand the English Language, most probably in a few years. He extended his hand, and told me in German auf wiedersehen.

I obtained work in a German factory where they did work for buildings – iron steps for the tall buildings. I was the only Jew among 25 German employees. They spoke English and German – and what Jew does not know German?

After working for a few years, I asked my foreman with whom I worked whether there was a possibility for me to get to understand the plans by which he worked, and whether I could ever work as he does? The Germans were very good machinists, he told me. If I want to become a very good worker, and wish to understand the plans and work on the plans as he did and perhaps even better, I must understand the language in which the plans were written. This would take me approximately three years.

I Bless the Day When I Become a Smith

In the winter of 1916, my friend from Yanova, the son of Leizer the chimneysweep, invited me to come to his wedding. The war was in progress, and I had not received any letter from my loved ones. I decided to accept the invitation, and I went to the wedding in Boston. This was the best thing that I could have done, for during the three years that I had been in the large industrial city of Pittsburg, I had never seen the moon, and the sun shone as if through a cloud, on account of the smoke from the large iron factories.

I decided then that I was not going to return to Pittsburg, so long as I could get a job. I got the job in which I am still working now, after 51= years. A few years later, I found out that he was from the same town as my mother, Kaplice, and he knew my mother, my father, and my grandfather. This had no connection to my employment there. My employment was a result of my abilities.

[Page 307]

I married my wife, who was beautiful even among the beautiful. We have three children. We gave them the best education. One son is a doctor and a teacher of the English language. Our daughter is an educated chemist and works as a librarian for chemistry books in the New York Public Library. One son is a musician, with a Master's Degree in music. He tells me, “Pa you earn your living from hard work, and I make a living playing.”

I did not come out of work with wealth. I bless the day when I became a smith in Yanova, and I am full of happiness as I state: The work of my hands is splendorous.

Translator's Footnotes

by Mari Winton (Moshe Vinitzky)

|

Our house, in which our parents lived and where I spent my childhood years, was located on Kovner Street, on the right side in the direction of Keidainer Street. The house was made of bricks and plastered with white lime. It was large and roomy enough for the entire family. There was a large fruit orchard near the house, and a smithy nearby.

We were known in Yanova as the family of Yuda Pesach's. My father, Pesach of blessed memory, was a pious Jew, but not fanatical. He was a good tradesman, and worked in the smithy together with his brother Yoel. They were master tradesmen, and they used to manufacture carriages and sleds that were not made to order. In the yard there were various spare parts from manufacturers, and my father used to sell them to the landowners from the region. He would also send merchandise to Zasliai and other towns.

My mother Chana, may G–d avenge her blood (murdered by the Germans) was much more pious than father. She was strict with kashruth. She was calm and good natured. Our family consisted of three sisters: Chaya Sarale, Esther and Moshel; and three brothers: Moshe (Mari), Berl, and Yudel. Father's earnings were sufficient for food and clothing for the family, and they sent the children to study in the cheders and yeshivas of Yanova.

In our house–workshop, we had one cow, and some hens and geese.

[Page 308]

Mother took care of them. We children used to love leading the cow to the field, going all around Stepan's pasture around Dizzy Mountain in Josefka.

I studied in the cheder of Yisrael–Ber on the highway. Later, I studied in the Yanover Yeshiva of Yudel Gurfinkel, who was called the Yellow Rosh Yeshiva teacher. Still later, I studied in the Ramailis Yeshiva in Vilna, on the Jewish street opposite the synagogue of the Vilna Gaon. In that Yeshiva, we studied Hebrew, Gemara, as well as Russian. I studied everything diligently. At that time, I felt an inner striving toward knowledge and culture. Unfortunately, this was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. I also had an inclination toward music. I studied music with Reuvke Baron. When the Jews were driven out of Yanova in 1915, we all started packing. In that process, my mandolin broke. That marked the end of my musical dream.

After packing up our belongings in a rented wagon, we set out in the direction of Zasliai on the eve of Shavuot. The edict of deportation did not apply to Zasliai, which belonged to the Vilna Gubernia. There, we lodged temporarily with our relative Yosef Burstein. A short time later, we traveled by train in freight wagons to Chernigov, Ukraine, and from there further on to Vitebsk. We remained there until the end of the war, when the Germans permitted us to return to Yanova. In the interim, I set myself up with work in “Zemelnia–Soyuz” in Gomel.

In 1918, I hatched a plan to set out on my own to Yanova. At that time, I belonged to the Youth Home. I stole my way in a train that transported Latvian refugees to Latvia. I did not have any documents. I hid for several nights in the buffers of the train cars. In Yanova, I found that our house was in ruins. The floor had caved in, and the entire yard was overgrown with tall grass. I went to consult with the Jewish policeman, Yisrael Stein. He advised me to travel to my relatives in Wilkomir, the Resnick family. After a brief consultation, they purchased my tickets to travel to Dvinsk, and from there, back to my parents. Beyond Dvinsk, I snuck over the German–Russian front, and arrived at my parents in Vitebsk. Hearing that I had been in Yanova, my sister Chaya–Sara stole across the border and once again went there, where she fainted from terror.

In 1919, the entire family returned to Yanova in a legal fashion. We renovated the house and workshop, and my father returned to his old work of smithing. Later, since I had already been in larger cities in Russia, Yanova was not alluring to me, and I decided to emigrate to America, where we had many relatives from both father's and mother's sides. I first traveled to Berlin. An aunt of mine lived there, mother's sister Esther Makel, who had gotten married and lived there. I lived with them for some time until I received the needed papers from my uncle in America, who had married my aunt.

My uncle owned a 150 acre tobacco farm in Connecticut. I worked at the tobacco plantation and earned very well. My sole desire at that time was to bring over the entire family to America. I sent papers to my sister Esther and brother Berl. My sister Moshel came a bit later. In the meantime, my father died, and my youngest brother Yudel took over

|

|

|||

| Y[israel]. Pagir in the American Army, 1918 | Y[israel]. Pagir in 1919 |

|

|

Below: the pictures of Grandfather and Grandmother – Yehuda and Faya Vinitzky In Yanova, they raised four families (3 brothers and 2 sisters)[2], and today in America, they number more than 200 |

|

|

|||

| At a corner of the Smiths Lane and the Old Street – Opnik's smithy: Ben–Zion, Avraham–Yitzchak (Mitzka), Mordechai, Yaakov, Fruma: The Brezin girls. The third house belongs to Alta the Milk Woman. |

||||

|

|

| Feiga (Shaham), Berl and Yudel Vinitzky |

|

|

|||

| Yoska the Crazy | ||||

[Page 309]

father's trade and thereby supported his family. We succeeded in bringing over our mother, but, after a short time, she decided to return to Yanova. She missed the remaining children in Yanova, to whom she was deeply connected. In 1935, our youngest brother Yudel came to America, along with his wife Tzipora Shaham whom he had married in the interim, and their two children. My sister Chaya–Sarale, who had married Aharon Segal, remained in Yanova. He was the founder of the movie theater of Yanova. We did not succeed in bringing them over, for they did not pay attention to my documents of request.

My mother Chana, my sister Chaya–Sarale, her husband Aharon Segal, and their three sons Moshe, Mordechai, and Chaim were among my relatives who were murdered.

My former tobacco farm is still called “Winton Park” after my name, and the street is called Winton Road[3]. Our family in America now consists of over 100 people. Most of them live in the city of Hartford. The nationalist education that we received in our youth has not worn off to this day. We are still Zionists, and work toward the upbuilding and strengthening of Israel. I travel to Israel every two years and stay with friends and Yanovers for an entire four months. One brother, Yudel, who is an active Revisionist[4] is giving up his business and desires to settle in Israel.

Translator's Footnotes

by Tzipora Winton (nee Shaham)

|

|

| Yudel and Tzipora [Shaham Winton] |

Our family was well–known. My father Shaya Shaham was a scholar, who knew how to study Gemara well, and also knew Hebrew well. For this, he can thank his education that he received in his home from his father Avraham–Yitzchak the Shochet [ritual slaughterer]. My father was a good–natured man. He loved societal work. He was traditional and observant, but not fanatical. He was a convinced Zionist, and was active in the Keren Kayemet [Jewish National Fund] and Keren Hayesod. He made sure to transmit the education that he received from Grandfather down to his own children.

[Page 310]

|

|

| Avraham–Yitzchak [Shaham] the Shochet |

My mother Geneshe was an exquisite Jewish mother. She was calm, peaceful, quiet, and dedicated with love and life to her family, her husband, and the education of her children.

We were four children: two sisters Sonia and Feiga[1], and the brothers Yosef and David. We all received a nationalistic education, and were active in Young Zion, Young Socialists, and Maccabee. We received our education in the cheders, the Talmud Torah, and later in the Tarbut School.

Veteran Yanova Residents

Incidentally I wish to note that my grandmother Rivka–Buna's ancestors (from my father's side) stem from an important family from Portugal. After the expulsion of the Jews from Portugal[2], their ancestors settled in France. They later moved to Lithuania and settled in Wilkomir. After their marriage, they settled in Yanova toward the end of 1799 or the beginning of 1800. This proves that we were veteran Yanova residents. My mother had four brothers and four sisters. In time, all of them emigrated to America, except for my mother and her brother Mottel who remained in Yanova. They were destined to be murdered by Hitler's murderous bands together with father.

From far–off America, memories of my childhood years swim around in my head. I always marvel at the calm of our town, especially in the early morning hours at sunrise. In the summer, the sun was always high on the horizon at 4:00 a.m., as the entire town was still in deep sleep. Only the shepherds who used to collect the cows and the goats in the pasture, as well as the tired women who brought the cows and goats to the collection point disturbed the early morning calm.

We Were Driven Out

The happy period of my youth continued until the outbreak of the First World War. My father was drafted into the army, and sent to Vilna and later to the deep interior of Russia. My mother remained alone with her four children.

One early morning, a division of Cossacks appeared in Yanova, appearing like a whirlwind through the streets. They held lances and spears in their hands, which they used to spear the challos that the women in the market kept in troughs to sell. We children stood in amazement at their dexterity, as we were full of fear.

On the eve of Shavuot of 1915, we found announcements posted that all the Jews must leave Yanova within 24 hours. One cannot imagine the extent of the misfortune that befell our

[Page 311]

town. People did not know where to go and run. People hired farmers with horses and wagons. They sold their goods and traveled to Kaisiadorys (Kashedar) and Zasliai. We contacted the Russian landowner Stepan, who owned many fields around Dizzy Mountain, and who knew my mother well. He sent two horses with drivers, and helped us sell a few valises, and we set off in the direction of the town of Zasliai. Along the way, we passed through the Boda Forests, which had been burnt down, seemingly by German agents. The Cossacks who were lodging in the surrounding area ordered us to put out the fire, and threatened us with whips. No amount of begging helped us, and we set off.

Thousands of refugees gathered in Zasliai. All of the houses, kloizes, and streets were overflowing. There was no place to lodge. People were in the fields. They set up kitchens, and cooked and ate in the open field. Since there was a railway station in Zasliai, people would enter the arriving trains and travel to wherever the train was going. We traveled to Poltava in Ukraine. There, we encountered a variety of tribulations – first, the 1917 Revolution, followed by several regimes: Red, White, in the pinnacle of the murderers Denikin, Kolchak, and Petliura. The Germans were also there for a brief period. After a full seven years of suffering, hunger and terror, we succeeded in coming home. We arrived in Yanova in 1921.

My first impression when I arrived from the city of Poltava was unexpected. The houses seemed small and low, and the streets were small. Slowly, we got accustomed to things, and began to lead a normal life.

In Maccabee and Young Hechalutz

Once, at an encounter with Ephraim Silberman, who was at the time a football player in the Kovno Maccabee, we decided to found a Maccabee club in Yanova. Leibl Zisla, who incidentally served as the first chairman, Shlomo–Ber Merovich, Velve Kerzner, and others joined us. I was among the first Maccabeeists. Being in Maccabee and hearing the frequent lectures about Israel from Yanosevich, Ivensky, the teacher Shaul Keidiansky and others, I decided to enter Young Hechalutz. This was in 1924. When I was 18 years old, I was accepted as a Chalutza [Zionist pioneer], and went through Hachshara in Memel. I returned home when aliya to Israel was temporarily halted. In the interim, I met my future husband Yehuda Vinitzky, also from Yanova. We got married, and that is how my pioneering ideals were buried.

To Israel via America

My husband Yudel also had nationalistic tendencies. He was a member of Maccabee, and was active in the Revisionist Party. After four years of family life, enriched by two children, the large Vinitzky family in America – primarily the oldest brother Moshe, invited us to come to them.

In 1935, we obtained papers and we set out. My family expanded in America. All three daughters and our son got married, and our family expanded with grandchildren. Everyone is living a happy life. Yudel and I remained alone. At this point, the pioneering feeling of our youth was reawakened, and we are contemplating settling in Israel among our Yanova friends and Jews.

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Jonava, Lithuania

Jonava, Lithuania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Jul 2018 by LA