|

|

|

by Yitzchak Ajzik Feffer

Translated by Selwyn Rose

|

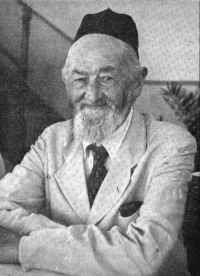

In the winter of 1956 when it was decided to publish “Greater Dubno” the memorial book for the Holocaust fallen, the editorial board approached a surviving town Elder, an old man who had accumulated much wisdom and knowledge during his long life, Mr. Yitzchak Ajzik Feffer who was at the time 94 years of age, in order to reveal to the readers of the book, a portrait of Dubno as it was clearly drawn in his memory. But before he was able to see the fruits of his labors he passed on.Mr. Yitzchak Ajzik Peretz, the tutor of Rabbi Elisha Feffer, one of the offspring of Rabbi Leyb Sharhass a student of the Ba'al Shem–Tov (May his name be preserved), was born in the village of Olik (Olyka) on the 5th of Av 1862. His mother was the granddaughter of Rabbi Yitzchak Ajzik leader of the Rabbinical Court of Korets (Koretz). He immigrated to Palestine during peace–time and settled in Petah–Tikvah and was one of the strong preachers of Torah. He lived to see his children and grand–children established in the Homeland and died in a good old age at 96. He was interred in Kfar Saba on Rosh Chodesh Iyyar 1958. May his soul be bound in the bundle of life.

[Columns 181-192]

by Ya'acov Nathaniel-Roitman

Translated by Selwyn Rose

The history of Dubno? Perhaps it is not as clear as a historian would like it to be – concrete and documented. The sad fact is that it is not possible for us to write a detailed chronological history of the rich Jewish experience steeped in tradition and faith as it was in Eastern Europe. In my grandfather's house, Rabbi Issachar-Dov ben Nehemiah Gershon, there was something that created an atmosphere of the past – it was a large trunk on wheels that occupied an honored place in the dining-room and study. The trunk was fitted with iron bands and an iron lock. Iron nails, the work of a blacksmith, were hammered into the bands and inside was a mixed collection of articles from the past like a small atlas with a stiffened cloth binding, elegant dresses from the time of my grandmother's wedding, a tooled leather document-case holding different certificates, a contract from Prince Lubormirski from the year 1742 and taxation records from the Napoleonic era and promissory-notes from the Counts of the Tarnowski, Miaczynski and Ittar families; silver spoons shaped like fishing-boats and carefully scrolled parchments and heavy silver rubles…there were also the historical records of the Municipal Council and the ancient Polish castle hidden in the misty air of the bridges and the old monasteries in the autumn-like twilight; but another “history” of deeds captured and presented in the form of well-written and documented reading books starting from some “beginning” never existed in our areas.

Perhaps earlier, when there was still an active Burial Society registering deaths and grave-sites of the deceased in the cemetery but what young person today, in the present century will find interest in those graves?

[Columns 183-184]

Among the Polish Christians, owners and landlords of great estates in the county such records certainly existed; they had it all – large castles, thick forests, hunting rifles and antique weapons, fields of rye and wheat, hop-fields and real library collections of classical literature and philosophers in books from earlier generations and more modern works. But among the Jewish people of Dubno at the beginning of the century there were only the physical remains of the bride and groom, slaughtered by the Cossacks while under their very wedding-canopy next to the Great Synagogue and the gravestones in the cemetery of the Torah luminaries of the Holy Community from four-hundred years earlier and of the Holy Ark of the synagogue, with its gilded floral decorations.

The Dubno Jews bought from the Ukrainians the produce of their fertile fields - rye, wheat, potatoes, sugar-beet, clover seed and corn; the collected produce was passed on to other Jewish traders, wholesalers, who in turn exported it to the countries of the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Empire, corresponding in documents written half in Hebrew and half in Yiddish; the agents in the Holy Community of Brody (Brod) had already concerned themselves in finding different agents in all the other European countries.

The Jews of Dubno built hop-kilns for drying and raking hops that had been brought in enormous sacks looking like feather pillow-cases two meters long, from the plantations of Czech and German settlements; they treated the bitter-smelling produce, sorting it by color and aroma and the year of its harvesting, drying and storing it in well-ventilated silos in order to ship to breweries in Germany, England and South Africa. Dubno's Jews harvested clover-seed cleansed it and transferred the valuable commodity to Danzig and northern countries, areas where the plant failed to thrive or germinate, or taverns and bars serving raisin-wine and mead. People who weren't traders, saloon-owners or hostellers sat on benches and tarred laces for the Gentiles' boots, sawed logs, worked the bellows in smithies, plastered walls or worked in cement works or brick foundries. Some made iron grills or swept the soot from factory chimneys…(no one in the Austro-Hungarian Empire had ever heard or seen, nor would they believe such a thing)- that a chimney-sweep with a blackened brush tied to his shoulder would, before their eyes enter a soot-filled chimney and sweep down on himself a cloud of soot; and what do you know – a Jew does it! And if a man had no trade and was a synagogue sexton, or cantor or – Heaven forbid – the town fool, isolated and living on the fringes of society and wandering around, even they never starved to death.

Most of the crafts and trades were present in Dubno and most of the artisans were Jewish and even house-servants and housemaids of the wealthy were Jewesses and served their employers with loyalty on into old age and their retirement to the old people's home. The Jews of Dubno always dressed in black wearing a 'kashket'[1] on their heads, a remainder from and reminder of, the law introduced by different European countries in the 19th Century concerning Jews and even though broad-brimmed European hats were available the Jews continued to wear the black, knitted 'kashket' and educated and scholarly Jews insisted on wearing such caps made of silk or velvet together with a long black frock-coat, slit at the back and buttoned all the way down to the waist-line on sunny and rainy days, with their trousers tucked into their boots. Shoes “booties” and sandals were permitted only to young children and babies. Long 'peyot' were not common in Dubno and were forbidden by the ordinance of the authorities but most of the male house-holders left their peyot untouched. Those who shaved were considered 'outsiders' and 'Epicureans' and their numbers small - Shmu'lik the watch-repairer, a known 'outsider' in town, of whom it was said that even on the Day of Atonement he didn't Fast –in his old age was eventually made 'Kommissar' of the Police and carried a sword – even he – grew a beard.

During my years as a youth not many devoted themselves to Torah; all traces of 'Enlightenment' and its Jewish counterpart, the 'Haskalah'[2] were forgotten and obliterated, or at best set aside and during the era of Avrom Ber Gotlober and his colleagues no attempt was made to deepen and broaden interest in it. If anyone in town asked about them they would likely be stoned. Official communities, like those of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with a community-head and leaders recognized by the authorities, were non-existent anywhere in Vohlin at the beginning of the century. The Municipality was in the hands of the small Christian minority one of whom was appointed and authorized to represent the Jewish community. A religious Rabbi and a “government appointed” Rabbi, a few pieces, not particularly impressive, of ritual religious articles and artifacts, a handful of public-spirited well-to-do citizens lobbying the town's Police Chief, the Governor and the provincial Governor – was all that represented the Holy Community of Greater Dubno at the end of the last century when the Jewish population numbered 14,257 souls compared to 7,108 Christians of all denominations – Catholics, Paraslavs (eastern Orthodox) and others. The town was not a center of Hassidism. A few sharp-minded scholars were sent to Kock (Kotzk) and later congregated in the Kloiz[3] of the Hassidim opposite the Great Synagogue a couple of Karlinists[4], a few others - 'fanatics' - as they slangily referred to the young Hassidim when they witnessed their exaggerated eagerness in lighting festival and memorial candles; there was in that pejorative nickname the very essence of muddied, inanity that attracted to itself all the idle and vacuous blindness of 'miracle-workers' and unthinking pedants. 'Fanatics' is exactly what they were.

[Columns 185-186]

And just who was an acceptable 'someone' in Dubno? A respected Jewish house-holder – a Jew living in the shadow of its walls, fronted by a large courtyard with a barn, a milk-cow and, from April to October, stacked-up logs of firewood drying in preparation for the winter to be easily chopped by hefty, broad-shouldered “Polishukim[5]” in the autumn; he had a place in the Study-House and his sons and grandchildren lived close-by. His livelihood brought him in a ruble or two by “permission and not prohibition”[6] of the local police-chief who received a “consideration” to “close his eyes”. Such a Jewish man would appear outside his house early in the morning and take his cow to pasture, light the fire for the copper boiler with wood-charcoal, and make sure that it is burning correctly with no bluish smoke escaping from the chimney. He would then take a long-handled broom and sweep his yard hither and thither, clean of all the dust and dirt down his sloping yard from the red-bricked sidewalk towards the street. This lead to an opportunity for a casual conversation and to sip a cup of tea with his neighbor from opposite and from there he would go to the Kloiz[7] and from there, at about eleven o'clock he allows himself to forsake the Holy One Blessed be He and turn his attention and hands to his own daily tasks and the needs of all flesh.

Of this you may be sure: The Jews of Dubno for generations had been successful businessmen. They were specialists in conducting business with landowners, barons, princes and other nobles acting as lumber and forestry agents and the erection of saw- and flour-mills; Polish- and stumbling Russian-speaking Jews, perhaps somewhat proud and arrogant, loving to joke at others' expense but serious among themselves, were careful in their dealings with the authorities and street-wise and wary when dealing with the “Katchapim”[8], reclusive within their community, relying solely on themselves and always aware of the eternal shadow of an invisible, undefined fear wafting above their heads.

*

The River Ikva (the name of the river is not Slavic; perhaps Celtic) encircling Dubno in a sweeping arc, is a typical Ukrainian river overflowing the entire area, swampy, potentially dangerous in places, with wide expanses of papyrus and other river-bank growth; there are deep and deadly fords seeming to be narrow enough to allow one to leap easily from one bank to the other. The river flows from south to north encompassing the town in a wide arc before turning to the north-west. To the east of the town are several small rivulets crossed by a bridge leading to the railroad station five kilometers distant from the town. At the peak of the arc, protected on three sides rises the fortified “palace” built of red bricks with its four rounded watchtowers at each corner. The sloping walls above the moat were without windows. There were arrow slits, wide on the inside, embedded all along the fortress walls, reminders of the snipers' nests from the days of the Khmelnitsky uprising. The deep moat, fed by the river in days of siege, surrounded it on all sides and cut the palace off from the town. At the foot of the precipice spread the old town of Dubno with its 170 Jewish houses with their two-thousand souls, according to the Polish census of 1765. In the days of Khmelnitsky there were perhaps more: “Yeven Mezulah”[9] mentions the slaughter of 4,000 souls in 1649 by Khmelnitsky's Cossacks. It is easy to identify the old town: at the town's center stood the Town Hall, a square solid building with thick walls and arched rooms. Four gates opening into the courtyard from all sides. At each gate stood ancient un-mounted cannon. They stand upright on end with the muzzles pointing skywards and rainwater easily enters the muzzles. In town there were shops all rented by Jews. In the Guffa building there were large halls and private apartments – the Municipality had vacated the building for some reason or other – and a “Citizens' Club” instituted a gambling casino there for Jews and Christians alike. South of the Municipality was the Jewish street – Sarnitzna Street, as it was called in Yiddish – an unmade street with no sidewalk, just mud and potholes. It divided into two with one side leading down towards the river and the second towards the drier land opening out near the Great Synagogue and the bath-house. The bath-house was built under the auspices of Prince Lubormirski in 1699 for public use – Jew and non-Jew alike. Next to the bath-house was a fenced-off area – a common grave with no tombstones. Here, Khmelnitsky (may his name be erased from memory), slaughtered the whole congregation with the sword and here, about a hundred years later, Gonta also slaughtered Jews. The externally unimpressive Guffa Synagogue was built in 1784, unlike the great synagogues of Lutsk and Liuboml (Libevne); its domed roof was the highest building in Dubno and shaped like a Jewish cap from the middle-ages. The inside of the synagogue was flooded with light its pale walls and two sturdy columns supported the ceiling. The Holy Ark was decorated with pure gold from the ground up to the roof-beams. On festivals the Ark was draped with a “Parochet”[10] of silk decorated and interwoven with silver thread. On the festival of the Giving of the Law an even more decorative Parochet was used covered with precious and colorful stones and pearls. Two synagogue officials would stand guard, one on each side to ensure that none of the celebrants, when closing the Ark and kissing the Parochet in reverence, bit off some of the stones or pearls… the whole community was intensely proud of its Holy Ark.

[Columns 187-188]

Several streets radiated out from the Municipality: the broad Szeroka, to the north, Sawaronya, Aleksandrowicz and Panienska where the wealthy lived. Newer areas of the town purchased from the Prince at the beginning of the 18th Century were Surmicze to the east, Zabramya to the west and Pantalia to the north, neighborhoods occupied by both Jews and Christians. The Monasteries and churches imparted to the town a somewhat Christian aura. Aleksandrowicz, at the heart of the Jewish town was dominated by a tall Polish-Catholic church with its white plastered walls shaded by chestnut trees and a grassy lawn. Its bells were not hung in the steeple but set into special niches constructed in the walls of the church. Placed along the wall in bas-relief were the Latin words Gloria Tibi Domine (Glory be to Thee O Lord) – and Dubno was not at the time completely Polish and all its signs were in the Slavic language. Nevertheless at the end of this rustic road in the suburb of Zabramya stands a Convent, one of its feet in street and the other on the slopes of the cliff overlooking a pleasant valley! The Convent was Orthodox and it was occupied by nuns. It is said that there was a tunnel burrowing into the bowels of the hill and running for a kilometer or two as far as the Palace. One day when the market square was being repaired opposite the Municipality, the surface collapsed and the tunnels were found beneath the roadway: they led away to both the left and the right in the direction to and from the convent and the palace. Everyone came to see skeletons and broken vessels, rusted swords and suchlike. The gaping hole from the collapse was filled with earth, fenced all around, and nobody asked any questions…!

There was another Monastery in town near the Municipal Gardens – a pleasant corner where black pigs could be seen burrowing in the plowed field. The big Monastery, occupied by Orthodox monks, surrounded by a wall with many bells attached, stood overlooking the wooded areas of Pantalia and the meandering Ikva beyond the town. When their Holy Days came, towards the end of Hanukah and a bitter frost covered the earth and the trees were bare of their leaves at the end of autumn, the sound of the bells spread from the four corners of the town: the bass bell of the Catholic church and the contesting counterpoint of the Uniates: ding, dong, ding, dong…filling us with loathing; it was something of an anathema! Judgment be upon you, Greater Dubno! Nevertheless, everyone heard and listened.

*

Have you ever seen houses with un-plastered blood-red brick walls separated by thin layers of lime? There were many of them in Dubno. Their windows were narrow with six panes of glass with rounded cornices like in the Study-House. Every house was like a Study-House! In front of each house a tiny porch, about one yard long and one yard wide, with two stools at the side and steps leading up from the side-walk. The side-walks were also constructed of red bricks place back-to-back and in the evening neighbors would sit outside and chat. Every house had a wide yard with a high gateway that was locked at night. There were stables in the yards for horses, a store-house for wood, a hut for a small arbor and a stall for a cow. There were cherry-trees, tomatoes and apples. At that time no trees were planted in the street because the gardens of the private houses stretched out onto the street preventing trees from being planted. The town was kept very clean, even in the market-place among the peddlers, carriage-drivers and phaetons, their black leather harness equipment and yokes were all clean and polished, the drivers, too in their rough and ready coarse fur coats wore broad decorated cummerbunds, there, too, among the wagon drivers – complete cleanliness. For Greater Dubno was like no other town in the province. There was no sewage or other plumbing. At the beginning of the century the population still drank water from the Ikva. The water-carriers, Jews who owned a barrel, would fill it using a funnel at the top and draw the water out through a tap at the bottom. They would go down to the river at dawn, enter the shallows with their horse and cart, moving about here and there up-stream filling buckets with the turbid waters and deliver the water to their customers in their homes charging the people according to the number of buckets delivered during the week. And wonder-of-wonders – the “Kapatchim”[11] came and sectioned off a central position in the market place and began busying themselves with pipes, drilling a hole in the ground, drawing from the hole and extracting from the thick milky-white mixture of gravel and water. They continued drilling and again drew out the rubble. The whole town one day came to see what was happening and behold – a powerful spout of crystal clear water came gushing up out of the ground spraying everything around…they tasted it and the water was like a sweetened summer drink. An artesian well! How? No one in town knew. Later they built a small brick roofed structure over the installation. All the water-drawers were elated. No longer did they have to go to the river and draw the dirty, turbid water. They just joined the queue at the tap and without lifting a finger the clear water simply flowed into the barrel – it was a great relief.

What was it Gotlober once said to his son-in-law the doctor, (that my father (Z”L) heard with his own ears one day when he went to the artesian well)?: “The religious folk may live and study the Holy Books for a hundred years and will find no mention of wells!” But along come the modern educated people and without their knowledge of the Torah they brought us artesian wells and for all that – although they're not mentioned - they exist!

[Columns 189-190]

But never mind the well – what about the telegraph!? Is it nothing, to be discounted? Or the railway?

“Oy! Die Eisenbahn, was ist gemacht gewarden, sie fahrt passagieren,…”[12]In any case – one must say that at the beginning of the present century the people of Dubno displayed a different spirit. The younger people began to exchange the traditional black frock-coat for a Christian manufactured shirt and those who wore hats on their head exchanged them for polished leather ones – just like the Christians. Even peddlers in the market-place began to use Russian almost automatically in their conversation, Heaven forbid!…The conflict between the two schools of educational methodology – the one leaning towards the Russian language and the traditional Heder-based system caused an exodus of the children from the Haderim and induced them to join the more modern system. Students appeared in town, Almighty G-d! In the summer heat with baskets of red cherries on the streets of the town, students suddenly appeared in white-as-snow uniforms, golden epaulettes and brass buttons and on the left side of their breast a small amulet – the insignia of their faculty; tall and handsome they were. The girls' were captivated at the sight awakening the desire both overt and hidden to join the movement to secular study, obtain a graduation certificate, making it all a reality.

One of the first among these was Kagani(?), clownish and energetic. Nevertheless he prayed with his father and owned a delicatessen, a likeable Jew, a member of the Baratz Study-House community. He knew how to read portions of the Torah accurately (he was a lawyer and Mayor during the days of the Revolution, swinging to the side of the Bolsheviks and back again. At the outbreak of war he was in Dubno. Nothing is known of him after that).

*

My grandfather's house, may he rest in peace, stood firmly and stubbornly against the “disease” of the movement to secularism and the grandchildren didn't wear shirts! There were other similar houses but the hops and clover traders were hard hit and sent their children to the private “Reali” Humanistic school in Kremnitz that had been built for the Jewish people with their own money and was like a stronghold against the Christians, while the girls were sent to the gymnasium that had been founded for girls in Dubno.

Mr. Zalman Ashkenazi, a prominent member of the Baratz Study-House where he was privileged to have a seat against the eastern wall adjacent to the Holy Ark, was wont to say: “Such a thing never happened! Your merit will not derive from your Russian Mandarin-style shirt or your dress-coat but by Zion!” A Jew will not be a man like all the men of creation unless his eyes envision the return to Zion. A Jew needs to have the Land of Israel as a possession. Where is the Land of Israel? They say – beyond Odessa. And is that far? – Yes, very! They have already journeyed to the Land of Israel from Berestechko. Berestechko compared to Dubno is like a ram compared to a bull. But they are there – young stalwart men, like oaks. Mr. Zalman didn't usually converse with the simple folk. He ran a pharmacy – or rather a warehouse of medicines because he wasn't a pharmacist. He sat against the eastern wall of the synagogue, his round face shaven clean like a priest, wrapped in a silver-embroidered prayer shawl and pince-nez on his nose and no one knew how to interpret and expound on the liturgical poems as well as he did. He was unique; a delegate to the first Congresses. The whole Study-House could “warm itself from his fire”. But what of the Land of Israel with our many sins, when the Russian lancers and the infantry brigade of her Imperial Majesty Maria-Feodorovna, who all man a garrison in Dubno right up against the walls of our house, decide to make war with our “comedian” warming with joy the hearts of all the grandchildren of our courtyard. And even the local artillery stands ready to relocate to somewhere in the Far East…

Gershon Hadmoni(?), a family member and a reserve soldier was also mobilized to be sent there but deserted and was already in Brody over the border. David Dushansky, a tailor's cutter, and an officer in a cavalry brigade, told our grandfather (may he rest in peace) explicitly that it will be – bitter. And it began, indeed, to be bitter. The clouds that hung over the town on the summer evenings foretold…something. The Russians who had been brought from the depths of Russia, broad-featured and fair-bearded, to construct a dam across the Ikva, expressed themselves in spirited singing rhythmically to the beat of their sledgehammers on the heavy sharpened logs used as pylons pounded into the earth and the bottom of the river: “O! The sledgehammers will beat on you…” – even they seemed to change their preferences and they had never seen Jews before in their lives! They lost the faith in the nation. Even Old Nikolai, our house-servant and Simon with his axe, who chopped wood in the courtyard throughout the days of winter…everything, seemed to be done under threat. We, the grandchildren, supervised the locking of the gates to the courtyard every evening, and that – we did.

We also completed among ourselves making and polishing iron daggers. I managed to acquire one broad enough, double-edged and about half a meter long with a good point and most evenings I spent polishing it. I fashioned a hilt as a good hand-hold and I had in my hand a dagger fit for a Cossack. My heart felt a little easier.

Dud'l, the eldest of we grandchildren at home, didn't take part with us “infants”. He disappeared each evening into the Pantalia marshes, over the bridge with five apprentices of artisans. It was an overnight activity. The artisans began to behave with an exaggerated sense of self-importance. As an old proverb says: “Shoemakers and tailors aren't men”…imagine! Dud'l, the son of Rabbi Shlomo Berish-Shmaryes escaping with apprentices - it's almost unbelievable! But we knew: and for sure so did he; and they have pistols! How, how?

[Columns 191-192]

Like this. Tie it to Nadziratan's nose(?)…Dud'l brought back from his nights in the Pantalia marshes osteo-tuberculosis but nothing happened in Dubno. Later on – years later, we understood: it was too close to the Imperial Russian Empire…here nothing could happen. But in Kishinev and Odessa things were different. And once again the imbeciles in town sneered at the crude words of the song: “In Harbin it's good but in Mukden it's better…[13]”

In the Study-Houses they debated the actions of General Tojo and passed judgment on General Stoessel, spoke about the Battle of Tsushima, the Commander of Port Arthur, Rozhdestvenskii, or just sought explanations and interpretations of insults and slurs, claiming there was no way out except “Svoboda” – Freedom! And one day it was announced that Tsar Nicolai had given them freedom! Freedom was declared in the first Duma and no one in the town knew whether to be joyful or to cry. It was a “dish” that we had not yet tasted. The provincial governor was also confused. In any case he immediately ordered an inspection of the central prison, repairing and repainting it, transferring the prisoners to the internal courtyards so no one outside would hear all the rumbling and speculation going on inside…and a sort of calm prevailed. The sounds coming from the workers in the workshops carried beyond the walls a different type of music, Russian and Jewish, that captured the hearts with their rich sweetness and wealth of courage.

And night after night trains rumbled down the railroad from east to west, from Kiev, Poltava and White Russia to Dubno and from there to Radywyliw, Brody and beyond that to the world. Only it should be far from Russia, as far as possible from “Freedom”.

Beyond the border, in Brody everything was grotesque and crazy: Streimelech, top hats, strange Jews with too many “please” and “thank you” and adjacent to the railroad station was an old man singing a song:

Maybe you want to know if a Russian is a man?

His boots are torn his fur-hat cocked to one side –

A Russian is a thief, a Russian is a thief.[14]

For all that he was there, beyond the border, every Russian Jew was already over the border.

[Columns 191-192]

by Agronomist Eng. Yisrael Feffer

Translated by Selwyn Rose

Education

A

Until the end of the 19th Century Jewish Dubno was a quiet town and education was carried on according to the earlier traditions: toddlers learned with various teachers in the Heder[1], among who was Rabbi Motel Loitzky–Bronstein who was very sharp–minded and witty. Above the Haderim for the tots were the Haderim of Torah studies, Rashi and Gemara where children studied for three or four years and the outstanding among the teachers was Rabbi Lazar Pollack. There were no Yeshivot[2] in Dubno but there were Study Houses that bore the style of a Yeshiva. The Haderim were under the approval of the authorities and the instructors were required to hold a teaching certificate; Rabbi Lazar Pollack had a certificate on the wall of his Heder and when a Russian inspector would appear in town teachers who hadn't one would send the pupils home. The Study Houses would be used as a sort of unlicensed “study studio”.

At the beginning of the present century two “un–classified” schools were founded in Dubno where school was taught in Russian. I was a pupil in one of them and I still remember two of the teachers: Mrs. Esther Spitzberg and Mr. Kromm. The un–classified schools prepared pupils for the municipal (classified) school where Russian was also the language of instruction. The municipal school was composed of three grades and two classes and the pupils wore school uniforms. It was difficult for Jewish children to be accepted into the municipal school and so their numbers were small although few of the Jewish pupils there doubted their capabilities and knowledge among the Ukrainian Christian children. The Christian children came

[Columns 193-194]

|

|

| Group of Russian students of the gymnasium in Dubno (1921) |

to the municipal school from the Church school. The head–master of the school was the inspector Doroschenko and his teachers were quite liberal. Fist–fights and arguments were a regular daily occurrence between the Jewish and Christian children but many of the Christian children needed the assistance of the Jewish pupils with their lessons and assignments and I well remember the pupil Avraham Shpak, who, with his strength and courage stood up well in the conflicts against all the Christian pupils in the school.

In the three lower grades the pupils, boys and girls, learned together while in the two higher grades they studied separately. The hours of study were from eight in the morning until two in the afternoon and the boys had some pre–military training and would take part in official parades. Every morning the priest would hold prayers before lessons and the Jewish pupils were obliged to attend; late arrival for the prayers was met with severe punishment. A conspicuous aim of the school was to instill in the pupils a patriotic feeling for Russia and festivals were held to honor Russian literary personalities in which the Jewish pupils played an active role. At the close of the school year certificates were distributed and school–leavers were permitted to work in pharmacies as apprentices. They were also eligible to enter the gymnasium.

A great advancement in education system in Dubno occurred in 1907 with the opening of the first Russian gymnasium in town and among the founders was a Polish pharmacist named Witecka. The excitement of the parents was immense and the rush to the gymnasium was great not only from the residents of the town but also from the local villages. The registration fee for the gymnasium was one–hundred rubles and a year's tuition fee 60 rubles – vast amounts for the period. Jewish pupils were accepted in the gymnasium without consideration of the Numerus Clausus.

But the joy of the beneficiaries was short–lived – the gymnasium didn't receive sufficient support and no privileges and closed two years later.

Two years later a government gymnasium was established in town for boys, where Jews were accepted after a difficult entrance exam but only according to the “norma” (Numerus Clausus) – 10% of the general student population. Many students studied in the government gymnasium and the young intelligentsia that was concentrated there and that tended even earlier towards the spirit of modernism, introduced sparkle and life into the Jewish youth circles in Dubno.

Because of the Numerus Clausus Jews were only accepted almost exclusively through influence, leaving it only for the wealthy families who were required to finance the studies of tens of non–Jewish students in order to obtain entrance for 1% of their children.

The zealousness of the young Jewish students, wearers of the uniform was intense but nevertheless they were obliged to attend religious classes in the afternoon because it was unthinkable in those days that a Jewish youth would go against his parents and disengage from his Jewish roots.

It should be pointed out that from the beginning of the nineties of the 19th Century there had been a gymnasium for girls with six classes in Dubno but without the right to obtain a matriculation certificate. Young Jewish girls who wanted to complete the gymnasium were forced even at the end of the first decade of the present century had to travel as far as Odessa where, at the gymnasium of Mrs. Jabotinsky–Kopp[3] they were able later to learn a profession, especially dentistry.

The government gymnasium for boys in Dubno existed for four years from 1910 until 1914 when, with the evacuation of all Russian institutions it moved to the town of Vovchansk in the Kharkov district. It returned to Dubno in 1916 and from then was headed for many years by Mr. Possfischel(?), a teacher who taught Latin and was of Czech origins. He was a very liberal man (I can testify to that because in 1922 he gave me a letter of recommendation

[Columns 195-196]

|

|

| Group of graduates of the Russian Gymnasium in Dubno (1921) |

to Mr. Krammersch, member of the Czech Parliament and among the leaders of the National–Democratic Party in Prague and editor of the “Narodni List” – “National Newspaper”, to help me obtain entrance to the University).

In addition to the schools mentioned, in 1910 a governmental Jewish school was opened and the teachers were graduates of courses for teachers in Grodno and Zhytomyr. The teachers of the school and the pupils wore a school uniform. The standard of this school was low, somewhat similar to a municipal school with two classes, while the municipal school would grant to graduates the status of a “class–two volunteer” that decreases military service from two–and–a–half years to one–and–a–half, something the Jewish school couldn't do.

With the conquest of Dubno by the Bolsheviks in 1919 education was renewed in the government gymnasium that was now established with seven departments instead of eight. The pupils were given a certain freedom and they organized and created a “Student Committee” with students from other schools. I was elected, together with Ilya Makhrok, of blessed memory, to the Students' Committee.

The government gymnasium continued to function during the era of the Hetman Skoropadski and Hetman Petliura, and included a solid amount of Ukrainian literature and language under the supervision of the previous management. But with the preponderance of Poles in town and the reversal of the government gymnasium to Polish – the wheel took a backward turn: the Jews were no longer accepted at the gymnasium and even those who had studied previously were met with difficulties with the examinations.

From this arose the need to establish a Polish–Jewish gymnasium and the first Head was Mr. Kammerman. The Chairman of the Parents' Committee was Mr. Avraham Karolnick.

An event of special note in Dubno regarding Jewish education was the school teaching in Hebrew:

In 1917, during the Kerensky administration, a school was established in Dubno named as the “Tarbut”[4] comprising six classes. Its first founders and teachers were the veteran teacher Elimelech Blei, of blessed memory, Mr. Balaban, of blessed memory and Mrs. Eichenbaum, may G–d avenge her blood. The establishment of the school was financially difficult because the parents were not yet accustomed to maintain a private school so a public committee was formed to concern itself with the maintenance of the school; at the head of the public committee were Avraham Huberman and Shimon Bar Yitzhak–Isaac Feffer. The school reached the peak of its development during the establishment of the Central Council of the Tarbut system in Poland.

[Columns 197-198]

|

|

| Girls' gymnasium (1914) |

Public and Party Activism

A

Public activism may have started in Dubno in 1917 after the Kerensky revolt, when freedom of action was given to all residents, including the Jews. Indeed, Jewish activism on a restricted level was occurring even before the revolution but that was based principally on “lobbying” and the activists were very few in number.

For various reasons there was a small group of Jews in Dubno close to the “centers of power” for instance: the Province Governor, who, by the very nature of his function, controlled lobbying through blackmail and bribery of the members of the administration in order to prevent unfavorable decrees and to protect the Jewish residents from economic and political set–backs. It is worth noting here that when there was a change of officials in the administration the Jews would pray that the incoming clerks and officials would not be worse than their predecessors – meaning that they, too, would accept bribes…

The Jewish activists were dedicated and extended help to all the needy without thought of reward and mentioned in this context are Volodya Mandelker and Mr. Avraham Korin, a very popular figure and a warm–hearted Jew who was elected in 1917 in a free vote as Chairman of the Jewish community thanks to his generosity.

The Jewish “lobby” was also activated in special cases, like securing an entrance to the gymnasium for a Jewish student beyond the “norma”, or obtaining a resident's permit in a village for Jews who were often under threat of expulsion because of a law from the eighties of the previous century that prohibited them from residing in the villages.

[Columns 199-200]

At the beginning of the revolution in February 1917 – the Kerensky revolution, the first signs of budding modern Jewish activism began: the first Jewish trade organization was established, as was the official Zionist Federation and a committee founded for election to the first municipal institute in Dubno – the Municipality – and the Jewish Community Council. A general public Jewish committee was also established in which activists from all layers of the community participated. The function of the committee was to represent the Jewish community before the authorities. The influence of the committee on the Jewish public was considerable. At its head was Ze'ev Burstein. A veteran loyal Zionist, a shop–owner, and there were two energetic activists, Avraham Huberman and Shmuel Barchash whose activism sprang from a sense of public responsibility and of a Jewish national awareness. The office of the Jewish Public Committee was located in the large central building of Mr. Greenberg and in the evenings his room hummed like a bee–hive with activity.

It was a period of general excitement, of liberalism and rosy hopes illuminating the skies of the Russian Empire and with it came a wide awakening of Jewish public and political activity. The Zionist Federation broadened and strengthened itself and acquired for itself control of the “Jewish street” while all public issues were curtailed in the Committee's offices until it its activities ceased after the free elections to the two important institutions – the Municipality and the official Jewish Community Council.

The elected Chairman of the Zionist Federation in Dubno during that same period was an excellent person, distinguished for manner and qualities, a short man, physically with an intelligent smile always on his lips: Moshe Zimmerman from Lubaczówk, near to Berestechko. He was submerged in Jewish and Hebrew culture, zealous for the Hebrew language and the possessor of superior qualities. He owned a library considered among the finest in town that contained the finest works of the end of the 19th and beginning of the present centuries. His two brothers, Haim, of blessed memory – and spared for a long life – Shmuel, immigrated to Palestine in 1908–1910 and were among the founders of Yavne'el in Lower Galilee.

The finest of the Jewish youth of Dubno were centered in the Zionist Federation at this time and among them were a large proportion of the Jewish students of the Russian gymnasium. Most of them later became conspicuous as active founders of “Hechalutz”[5] and “Hashomer Ha–Tsa'ir”[6] and the Jewish sports club. Together they undertook propaganda activities in the elections for the proposed all–Russia congress and to struggle against the “Bund” and the “Social Zionists”

Nevertheless the “Bund” had many supporters but few of them were local from Dubno but mainly from recently demobilized soldiers at that time stationed in the villages and towns near the Front. These soldiers had the right to vote in the places where they were stationed although their influence on the Jewish public was not great. It is true that a strong supporter of the “Bund” and a brilliant orator was Dr. Levinson, an educated man who succeeded in attracting many listeners until it was discovered that he had ties with the “Bund”. Most of the meetings took place in the synagogue in the absence of a suitable public facility and at one of the meetings Dr. Levinson tried enthusiastically to prove that the Socialist swindle was a Jewish phenomenon from ancient days and brought as proof the deceit of our biblical Patriarch Jacob in depriving his brother Esau of his birthright by fraud as a clear case of Socialist economic preference…before he had finished speaking most of the audience rose in anger and left the synagogue and Dr. Levinson was obliged to reduce his activities with the “Bund”. His influence among the general public soon disappeared as if it had never been.

A small party that earned for itself some attention was the Zionist Socialist Workers' Party; at its head was Dr. Borodianski who was also a doctor in the military and Mikhail Huberman, born in Dubno, talented and an dedicated public activist. The small Polish “People's Party”, headed by the multi–active attorney Mr. Yosef Pinchoshovitz also claimed some importance and “wide influence on a broad mass of the population”. Indeed, it was not worthwhile for any small party to engage in the political struggle…

These were great days for the Jews of Dubno. At the head of the list for the all–Russia legislative council representing the Jews of Vohlin stood Rabbi Dr. Mazeh of Moscow and for the first time in Dubno's history Jews were elected to the city Council by most of the population: Avrasha Kahana, a young lawyer well–known and liked by all the residents; Eliza Kagan, an educated young woman; the son of Rabbi Yisroel Sofer Stam[7] as the delegate of the Social Democrats and Jewish social revolutionary representing soldiers quartered in the town who were enfranchised. This town council was active until the Hetman Skoropadski head of the Ukrainian independence movement revolution in 1918.

During this same period a small group of Jewish Bolsheviks began to become conspicuous, drawing encouragement from the success of the Bolshevik revolution throughout Russia. Among the activists in this group were two students from the University of Kharkov, Aaron Kagan and Joel Kellner.

The Bolshevik group did not manage to gain for itself

[Columns 201-202]

support from the Jewish public of Dubno. In fact the opposite is the case: its activities gradually faded during the turbulent changes in government in the fateful years 1918/1919 – from the overthrow of Hetman Skoropadski by Hetman Petliura; the weakening of Petliura's regime by the local terrorist gangs and his final removal by the conquering army of Poland, the temporary authority of the Bolsheviks on the county and then the re–conquest by Poland.

In conclusion, it is fitting to note that the activities of the Jewish public of Dubno in the years 1917–1919 were not a spontaneous awakening caused by events of the moment but the result of the new spirit that came about in Dubno during the years of the Russian revolution of the 1903–1905. As a matter of fact, the Jewish “proletariat” in Dubno was none other than a small weak number of artisans, a few apprentices and a passing propagandist who remained in Dubno for a short while, although the revolutionary spirit and the pogroms that brought on their wings awakened the young people in town to the need organize itself for self–defense.

The Jewish “Defense” was created in those years in the underground organized in “quartets” at the head of which were young Jewish social revolutionaries. One of them, David Ber Shlomo Roitman, was training his quartet in small arms in the swamps of Pantalia when he caught a severe cold that developed into tuberculosis from which he never recovered. Another young person who was active in the “Defense” organization was Moshe Rosenfeld who was tried for revolutionary activities and sentenced to two years in the infamous Shlisselburg prison; he was much publicized in those days.

Self–Defense in Dubno in 1919

The idea of self–defense for the Jews of Dubno was born in the days of the 1903–1905 Revolution and the seedlings began sprouting already in those early days although the organization as such began to exist only with the fall of the Kerensky regime in 1917 and the changes in authority that came following after: the Ukrainian Hetman rulers, Skoropadski and Petliura, the first Polish conquest, the Bolshevik rule, and the re–conquest by Poland. These were two nightmare years for the Jews.

Because of the weakening local authority and the continuing confusion in town there began a period of pillaging and looting by gangs of hooligans – beginning with members of the underworld and different elements of hooligans from Dubno itself and spreading to gangs of youths from neighboring villages like Palcza and others – who would fall upon the Jews and burst into their houses in the evening claiming they were searching for weapons. When they didn't find anything they would simply demand “ransom” money. The Jews, fearful for their lives would pay and pay again and again to anyone that threatened them.

In view of that situation a few young people aged between 18 and 30, all of them volunteers who had obtained weapons in various ways, mainly by purchasing them from the Ukrainians, banded together and organized themselves for self–defense. The Ukrainians themselves had many weapons, some from the armed forces who were in the county during the First World War – the Russians, the Germans and the Austrians. The price of a military rifle, the principal weapon of the “Hagana”[8] in Dubno was then 10 rubles, a substantial sum in those days. They also obtained a Russian machine–gun and a member, Moshe Barchash, who had served in the Russian army as a machine–gunner, knew how to operate it. The only motorized vehicle in Dubno at the time was a used Russian military truck, owned by the Hagana. It served them as a support vehicle in times of trouble and as a tool to transport a strike–force in an attack.

The Hagana commander in Dubno was Yasha (Ya'acov) Horowitz the son of Rabbi Shmuel Halevi Ish–Horowitz a descendant of Rabbi Isaiah ben Abraham Horowitz, and the command–post was situated in the building formerly used as the Jewish gymnasium. The members of Hagana fulfilled their duties on a voluntary basis with no consideration of day or hours and with nightfall they would all assemble in the command–post for a briefing. Because of the small number of members it was impossible to patrol the distant suburbs of town, so continuously patrols were organized in pairs and they would walk the streets armed with rifles and ammunition and from time–to–time report in to the command–post on what was happening in the town.

We will recall here one “military” action of the Hagana that was carried out one evening against Ukrainian farmers. It was one Sunday, market–day in town and rumors arrived in the command–post that Ukrainian farmers, who had come to town for the weekly market, were looting a warehouse of Petliura's army. While the looting of warehouses didn't affect the Jews, the farmers were likely to become “encouraged” from their own activities and continue on to attack the Jews of town. Because of this a “platoon” of ten members of the Hagana was sent in order to disperse the crowd. The group fired a couple of shots in the air but the crowd didn't disperse but fired back. Then re–enforcements were brought from the command–post, and an exchange of fire went on for some time and one of them was hit in the stomach – the son of Yehezkiel the glazier. Eventually they dispersed by the Hagana and order returned.

Among the members of the Hagana in Dubno at the time we will mention here: Yasha (Ya'acov) Horowitz, Moshe Pinchosovich, Dossia Koren, Genia Meizlish of blessed memory, Moshe Barchash and the writer of these lines.

[Columns 203-204]

Jewish Life in Dubno[i]

In Dubno, like in other provincial towns there were journals like the one referred to here with writers who were not actually professional journalists but possessors of a broad education and high intelligence. They would sign their pieces not with their real names but with an acrostic. From among a wealth of articles those that give us a clear picture from the “class war” spirit of that time, such as the special enforced tax on meat and candles as was prevalent in the Tsarist period and the enforcers of the tax – those with the right to enforce the tax on the Jewish residents as a fixed payment in advance, to the authorities – made for themselves a nice business and controlled the community, community interests, education and more.

The Tax of 1884

With the approach of the elections due to take place in the County town Zhytomyr, house–holders, who including those of the rich and established class, received authorization to represent the Jewish public before the government; and in order to avoid the bureaucratic tangle of correspondence and requests, it was decided to record those with the appropriate authorization according to their given names. It was agreed with them that all the profits will be used to maintain public institutions. But already in the first year of its administration it became clear that the public representatives were not worthy of the trust placed in them. Not only were these administrators elected to public office failing to transfer funds they received to the community throughout the year, they also refused to lower the price of meat that was higher than the fixed price in neighboring communities such as Róvne, Lutsk and others. While they fixed the price of meat on the bone at 15 kopeks a pound the price in surrounding communities was 10 kopecks a pound for boneless meat.

The tax administrators, who had the mutually agreed authority, had no wish to have it taken from their hands; they became aggressive and imposed themselves on the public by force. Thus, in order to silence their principle opponents, they were not ashamed to inform the authorities of those people from close by who came to town and had no rights to settle there since it was situated with fifty kilometers of the border. After that they didn't hesitate to “rub salt in an open wound” to draw “hoi–polloi” to their side and the “hoi polloi” acquiesced that the price of meat in the first half of the year will be 14 kopecks and in the second half 15 kopecks a pound, as it was in 1883.

The sale of 240 thousand pounds of meat in the year 1884 generated twelve–thousand rubles in taxes that were supposed to enter the public coffers but the uncompromising controllers poured the funds into their own pockets and not a kopeck to the needs of the community. In 1883 2,800 rubles from these taxes were transferred to public funds for its institutions of which 1,000 went to the hospital while in the following 1884 the government representatives exploited the public and enriched themselves at the direct expense of the community.

It is superfluous to point out that the promises of the elected officials to transfer funds for building the bridge over the river for the water–carriers drawing water from the river and also the erection of a public bath–house for the community fell by the way–side.

When complaints were made against them saying “Is this possible?” – there were those who opposed them citing their responsibility to the public: “The Jewish people are a rebellious people of ‘complainers’. Didn't the Children of Israel rebel against Moses our Teacher and failed to trust him?” And indeed they continued to enrich themselves.

Professional education in 1886

One of the journalists writing that year wrote about the relationship that was shown by the fortunate and wealthy towards their less–fortunate brethren, struggling daily to make a living, not succeeding and with no one to assist them. There were many poor children in the town but only one person of means spared a thought for them. Four years previously he had sent four of them as apprentices to various artisans where they learnt the trade and had even paid for each of the four an annual fee, while children who were physically unable to learn a trade were sent by him to study under teachers and scholars. All these children – “his” children – were distinguished by their uniform which he also supplied for them. The children who did well in their apprenticeship had their handiwork sent to the “Artisans' Foundation” in Petersburg and the administration of the Foundation for Fair Recompense. Nevertheless, as we know “One swallow doth not a summer make”! And one man cannot for an extended period, do on his own the work required by an entire institution and the work done by this one man found no one to succeed him and it stopped.

The situation for the children learning in the “Talmud Torah[9]” was also difficult. The teachers were without elementary education, the hygiene and sanitary facilities were beneath even the lowest of standards and the children were dressed in what virtually amounted to rags, crammed into one narrow and airless room

[Columns 205-206]

with inadequate illumination. “One's heart goes out to these poor unhappy children whom fate had dealt so harshly with” – the writer concluded.

The Cholera Plague of 1885

After the Great Fire that occurred in town, the over–crowding became critical to the point of endangering health and influenced directly the number of people falling sick. The residents were afraid to inform the authorities of being ill lest they were confined to the hospital where – as rumor had it – the patients were being poisoned. The panic was great; residents ran from town and carried their disease with them. The army left town and with them the military doctors and the small number of doctors in town was insufficient to cope and help was needed from outside of town.

A wooden hut was erected where free tea and boiled water were available for all. The creation of a system of rotation was also suggested with the doctors providing emergency treatment. The provincial governor proposed collecting money from the affluent to fund the struggle against the cholera outbreak. A total of four hundred rubles was collected while to finance a wedding in the cemetery – which superstition said would halt the plague – five hundred rubles were collected!

In the meantime the plague did not cease and the results were somber and until all the good suggestions from here and there bore fruit, the atmosphere of fear did its work. Many of the workers left town and the refurbishing of the destroyed town after the Great Fire ceased. Eventually a public committee was formed with several tens of young volunteers for sanitary work and thanks to their efforts and dedication the mortality rate from the dreadful illness gradually began to fall.

The Great Fire of 1895

We are not talking here about the occasional fire that breaks out now and again because of someone's carelessness that consumes one or two houses but a serious massive blaze that flares up and consumes entire neighborhoods and changes the lives of many people overnight. One must remember: these houses were far from proof against fire and their owners couldn't expect any compensation for their losses as happens today.

A fire such as that occurred in 1895 and the damage inflicted was immense to the extent that a public committee had to be created to assist the victims. The committee used the monthly journal “Kronika Wostoka” to ask for financial help for the needy to be sent to two committee members: Doctor Norawsky (a Pole) and Ch. Margoles, the government accredited Rabbi.

The Community in 1891

The Jewish residents of town were mainly traders and businessmen and artisans and compassionate. Their economic position was hard and not a few were impoverished and formed the “proletariat” and there was no public body that could offer help. A few years ago one of the public figures in town suggested forming a charitable organization to help the needy but because of diverging opinions the idea failed to germinate. The community cannot be forgiven for failing to act after all, part of its function as a communal body would be to come to the assistance of the needy. There is no forgiveness either for the religious observation “To sit and do nothing is preferable”[10]. “Doing nothing” seems to matter to them more than their concern of “Kosher and Treiff[11]” while all the other troubles in our Jewish world didn't touch them at all? Are they really exempt from keeping the specific commandment: “…and if thy brother be waxen poor…[12]”!?

The Struggle for the Rabbinate

The fight for the position of the additional Rabbi in Greater Dubno began a few years before the outbreak of the First World War. At the time, the seat of the Chief Rabbi was occupied by Rabbi Mendele Rosenfeld while his younger brother Velvel served as Dayan[13]. Both of them served as town Rabbis for almost a full generation. Their dwelling place was in the center of town although their “domain” stretched all over the town, its neighborhoods and even its more distant suburbs. One of the important elements under their control was that of slaughtering. There were several distinguished slaughterers in Dubno at the time among them Rabbi Maril and Rabbi Sandor Sakiler.

Regarding slaughtering matters there was a special regime in Dubno controlled rigidly by Rabbi Mendele assisted by his loyal aide Rabbi Ben–Tzion who acted as a sort of “adjutant” although he was much younger than the other slaughterers and was not more knowledgeable in matters of orthodoxy than they were. One of the reasons for his strictness towards most of the Trisk slaughterers of the town was because they were of the “Hasidim”[14] sect – Rabbi Maril and his son–in–law Rabbi Aharon and also Rabbi Sandor Sakiler were members of the Hasidei–Turiisk (Turzysk, Turiys'k) sect and some of the slaughterers were from the Hasidei–Ołyka (Olik, Olika) sect – while he, Rabbi Mendele, was from the “Mitnagdim” sect. (See endnote #14).

Rabbi Maril married his daughter to a young man named Eliyahu Guttmann, a great scholar of the Torah and an ordained Rabbi and ritual slaughterer. Because Rabbi Maril was already getting old he wanted transfer his power to his son–in–law so he took him to the slaughter–house from time–to–time to instruct him in the practicalities of slaughtering, as was common in those days among the slaughterers.

[Columns 207-208]

Rabbi Mendele knew of this but he didn't react to the “irregularity” of Rabbi Maril. When Rabbi Maril announced publicly his intention to delegate his position to his son–in–law Rabbi Eliyahu, Rabbi Mendele in his wrath began persecuting Rabbi Maril whenever and however he could.

Now all the Trisk Hasidim came to the support of Rabbi Maril. At their head were Rabbi Isaac Feffer and Rabbi Eliezer Goldfarb, both of them confirmed Hasidim. The synagogue of the Trisk Hasidim was in turmoil and was used as a campaign headquarters supporting Rabbi Maril's attempt to pass on the slaughter administration to his son–in–law Rabbi Eliyahu as an “inheritance”. The dispute and the furor went on for several months and in the meantime the support for Rabbi Mendele in his resistance to the inheritance grew and solidified and the opposing forces were about equally balanced.

Then the supporters of Rabbi Maril tried something else and some of the important people from the suburb of Surmicze came out with the rallying–call “All of us stand together” and invited Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmann, the son–in–law of Rabbi Maril to take the position of Rabbi of the suburb. Chief among the candidates for the Rabbinate of Surmicze was Rabbi Eliezer Goldfarb, a rich and respected Jew who even forewent part of his salary as Rabbi. The salaries and funding for ritual objects, the Rabbis and slaughterers were paid for from incomes from the taxes but because Rabbi Mendele and his supporters were in control and refused to recognize Rabbi Eliyahu, he was forced to look elsewhere for a living.

When Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmann became installed as Rabbi of Surmicze and began to function with his “Responsa”[15] it became clear that he was a highly intelligent man and pleasant to all humanity causing many people to turn to him for solutions to all manner of problems as arbitrator and adjudicator even in disputes of a private or business matter. Nevertheless it was hard for him to make a living although his status as the Rabbi of Surmicze was secure and steadfast. The public recognized him and referred to him as “the ‘young’ Rabbi while Rabbi Mendele was known as “the ‘old’ Rabbi”. Although his residence was in Surmicze, a distant suburb, he usually came to town each Shabbat to deliver a sermon before the afternoon prayer in the “Braslaw”[16] synagogue where he also expounded on a page of the “Gemara”[17]. He was extremely learned and his sermons captured the attention of a growing number of listeners. In this he exceeded Rabbi Mendele who was not accustomed to preach.

When the First World War broke out in 1914 many of Dubno's residents left town and with them Rabbi Mendele who settled in the provincial capital Zhytomyr. Rabbi Eliyahu remained the sole Rabbi in Dubno and he remained there with its Jews throughout the Austrian conquest and officiated as the sole Rabbi after the re–conquest of the town by the Russians. During these years he became extremely well–liked by the Jewish townspeople and with the return of Rabbi Mendele after a two–year absence from Dubno they both officiated as Rabbis. With the death of Rabbi Mendele at an advanced age his son, Rabbi Hershel inherited his place and after the Polish conquest officiated as the accredited and official Rabbi. He and Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmann together shared the seat of Chief Rabbi until they were taken by the Nazis to an extermination camp where they died a martyr's death.

Under Austrian Rule

After the outbreak of war the town of Dubno, which lay about fifty kilometers from the Austrian border, became the base of the various armies that passed through. The Russian army, opened with an attack on the Austrian Emperor's forces, beat them and got as far as the Carpathian Mountains. Thousands of Austrian prisoners, many of them torn and battered passed through the town. However it was not long before the Austrian army, with the help of the German army, drove the Russians back and by the beginning of autumn 1915, the approach of Rosh Hashanah and the Day of Atonement the Austrians had reached the town and retaken it.

A group of us young people was standing near our homes on Soroka Street when the Austrian cavalry came in and approached us. “Which way to the bridge?” they asked in German. We pointed out the direction of the bridge near the flour mill and scampered off. The following day the entire town was in Austrian hands while the Tsar's forces dug in out of town over the other side of the river Ikva.

For a period of 10 months the town was cut off on one side from Russia and as a front–line town from the conquering Austrian state because of the military situation – like a sort of island. The conquering Austrians related politely and generously to the population and the Jewish sector in particular felt it after having suffered badly at the crude and cruel hands of the Tsarist Russians simply because they were Jews, especially so as Jews in a border town with the Austrian enemy. Thousands of Jews in border towns had been peremptorily exiled from their homes far away into the hinterland by the order of the Grand Duke Nicolai Nikolayevich (the uncle of Tsar Nicolai II) because the lack of trust in their loyalty to the Russian authorities. They were even thought of as spies and traitors. Nevertheless the order, so far as Dubno was concerned, never went into effect from lack of time.

During the early period of the Austrian authority over the town, the Jewish residents felt reasonably free and at ease (most of the Russian residents fled the town with the retreating Russian forces); the shops were open and goods were being sold to whoever wanted them – although at a higher price than normal. But soon shortages in foodstuffs began to be felt because of the besieged town being cut off and the supplies couldn't get through.

On Rosh Hashanah in the middle of Mussaph (additional prayer), when the synagogues were full of praying people, the Russians suddenly began shelling the town from across the river directing their fire towards the area of the synagogues as “a present for the festival”. The panic that ensued was great but the bombardment ended without casualties.

It was not many days until the residents began to feel the effect of the military regime. The homes on the streets alongside the river were emptied of their residents on the orders of the military commander and the homes cordoned off with barbed wire. The residents were evacuated and moved into the houses abandoned by the Russians who had departed with the army. The situation regarding food supplies worsened, especially for the poor people for whom no one cared.

As usual the confusion of the present situation gave rise to the growth of unruly behavior. There were those who were close to the top military authorities who were able to obtain travel permits to travel deep into the country far from the front – something more difficult than “parting the Red Sea”!

A variety of supplies were brought to the besieged town that was sold at exorbitant prices. There were also some members of “the fair sex” close to power that succeeded in getting permits for some “traders” who then became rich – at the expense, of course, of most of the residents.

In the Spring of 1916 the Russian army began an attack under the command of General Brusilov and repelled the conquering Austrians to distant Austrian Galicia. With the liberation of the town many of the exiled refuges began streaming back to their homes and the economic situation together with the opportunities of making a living multiplied. A period of relief and affluence began and during two years the residents lived on a rising economic tide of fruitfulness and prosperity. Then came the Bolshevik Revolution and turned everything upside down again…

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dubno, Ukraine

Dubno, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 14 Oct 2020 by JH