|

|

|

[Page 164]

Dorohusk

51°10' 23°48'

(Dorohusk, Poland)

Translated by Yael Chaver

[Page 165]

|

|

By Chayim Listinger

Translated by Yael Chaver

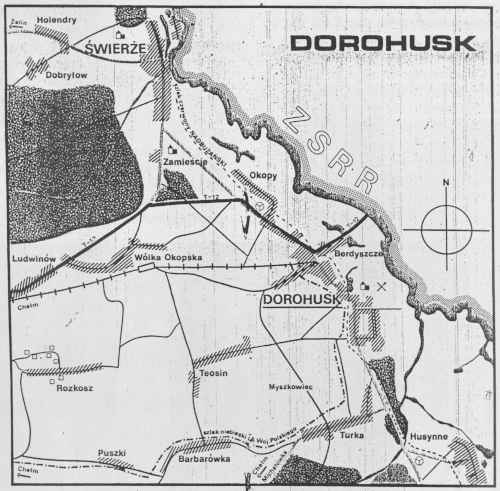

Dorohusk lies on the banks of the Bug River, formerly the border between Poland and Ukraine, now the border between Poland and Russia.[1] Before 1939, Dorohusk was a lively town with rich Jewish life. I do not remember the number of Jews in the town and its surroundings. The train station was in the center of town, and the lines led to the east as well as to central Poland and the towns in the area. The station served passengers from all the towns and villages around. It was also the center of Jewish life, with shops clustered around it. Among the shop-owners, I remember Bornshtein, or Alter, as well as my uncle Zvi Verber.

I was born in Dorohusk in 1927, into a large, ramified family – especially on my mother's side; it included brothers, sisters, grandfather, and many cousins. One of these was my grandfather (of blessed memory), Noach Verber; he taught Jewish subjects and Hebrew to generations of students. My aunts (Mother's sisters) were members of the Beitar youth movement; they wore the uniforms and did military-style drills. They were among the first in town to speak Hebrew.

My grandfather, an impressive-looking man with a long, wide beard, hosted all the grandchildren during the two months of summer vacation. Yiddish and Hebrew songs then constantly resounded in the area. One of the girls from Warsaw acted in the play The Little Dove.[2] The last celebration of Simchat Torah, a year before the start of World War II, was a very lively occasion: people danced their way from house to house, ate and drank, and danced atop tables. The onlookers hoped it would not be the last happy occasion in town.

|

|

[Page 167]

The town was taken by the Soviet army at the end of 1939. According to the terms of the treaty with Germany, the Soviet army then retreated across the Bug River.[3] The Soviets convinced us to cross the river with them, as they controlled the other bank of the river. Besides, we had relatives on that side. We were not permitted to stay close to the border and had to roam deep into Russia. Conditions were harsh. We worked at tree-felling in the forests. We lost touch with some family members in the course of moving but were able to reconnect later.

|

|

When the war ended, we returned to Dorohusk, and found that none of our relatives had survived there, like the rest of the Jews in Poland. It was too dangerous to travel and conduct a thorough search for family members, due to anti-Semitism. After several months, we continued through Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Germany, to Palestine. Over the years, we raised families. Our children married, and we have six grandchildren.

In recent years, with increased public attention to the Holocaust, I began thinking of returning to Poland, to find out what had remained. In August 1991, we joined a small group of 28 people, mostly natives of Poland, with some natives of Israel and Jews from north Africa. We travelled though present-day Warsaw, whose 500,000 Jews had been exterminated, and continued to the Treblinka, Lublin, and Majdanek death camps. Finally, we spent several hours in Dorohusk.

My uncle's house was one of the few pre-war buildings to survive. The town looked completely different, with no trace of the past. Life is normal, with none of the Jews that had been murdered. The school still stood in its spot, as did a few other structures.

We continued the trip with the group and visited the Auschwitz death camp, as well as Birkenau, Cracow, Łódź, and Czestochowa. We saw very few Jews, who seemed miserable. I'd like to note that we marked our victory over the Nazis by holding eight memorial services, flying the Israeli flag, and singing the Israeli anthem, in the presence of many visitors – among them youth groups from Germany and elsewhere. This was our message to young people who were born after the Holocaust and to Jews of other countries that were untouched by the devastation. We must guard our independence at any price, as our current enemies are eager to destroy us.

This marked the closing of a fifty-year long circle.

[Page 168]

|

|

Translator's Footnotes

By Yisrael Alter

Translated by Yael Chaver

In 1935, I decided to emigrate to Palestine. My mother and brothers vetoed this idea. At that time, a group of young people wanting to emigrate there was organized. They planned to do part of the way on foot. When Mother heard, she said, “Riding would be better than walking” – and that was what I wanted to hear. However, before making a final decision, Mother went to the rabbi and told him about it. The rabbi wanted to know my name. When she told him, he said, “Let him go. Your Yisrael will have the same fate as all the people of Israel.”

I reached the country in 1936, at age 20. The Labor Federation's regulations at the time permitted unmarried men such as me to work only four days a week. As I was a good worker, my boss, the project's contractor, pressured me to work six days a week. The only problem was the Federation's inspector. I was therefore instructed to hide somewhere when I heard the announcement “He's coming!” One morning, when I was sure I was working on the first floor of a building, I heard the call, and instinctively jumped off the scaffolding. I was actually on the second floor. Luckily, I landed in a pile of sand.

In 1938, I received ship's passage to visit Dorohusk. Before leaving, I submitted a request to become a citizen of British Mandate Palestine. After I received citizenship, I requested a visa for Poland, and was granted one for a three-week stay. I knew that my family at home would make it difficult for me to return to Palestine and would try to convince me to stay in Poland. Indeed, they asked me to stay for at least a year. I knew that the Polish government would not extend my visa, but my family was convinced that they had the right connections to make this happen. In fact, the Polish authorities wouldn't let me stay even a day beyond three months. In this case, Polish anti-Semitism helped, because the war broke out several seeks after I left Poland, and my entire family was murdered by the Nazis.

On my trip from Palestine, I travelled by train, where I encountered the same anti-Semitism that I remembered from my childhood. I entered a train car where three Polish intellectuals were sitting, and a lively conversation disparaging Jews developed. All the Jewish “characteristics” were mentioned: Jews were dishonest, cheated non-Jews in business, etc. Each of the Poles described “his” Jews. I was present during most of the conversation, and joined in. At one point, I told them about dishonesty among non-Jewish merchants (they took me for a non-Jew).

When we stopped at a station about fifty kilometers from Dorohusk, my cousin Ya'akov Alter (of blessed memory) entered the car. He was very happy to see me, and we started speaking fluent Yiddish. The non-Jews asked me about my connection with the Jew and I said that he was my cousin. Embarrassed, they left the car.

I started on my way back to Palestine in 1938, and travelled through Warsaw. On Twarda St., I saw Polish students beating a Jew. I ran to the policeman at the corner and called to him to help the person being beaten on the street. He responded, “That's not a person – that's a Jew.”

I returned to Palestine, but my family – my mother. Chaya Dvora, my sister Rachel, and my brothers Mordechai, David, and Pinchas stayed in Poland. I heard nothing more from them. I'd like to take this opportunity to mention their names, in case one of the miracles we hear about sometimes should happen in this case as well. I did hear once about my brother Pinchas: a Polish soldier told me that they had served in the same unit. Two other brothers, Avraham and Alter (both of blessed memory) who were sent to Siberia by the Russians survived and reached Israel in 1962.

Translated by Yael Chaver

My mother was born on April 15, 1932, in Dorohusk, Poland, to her parents Bella and Eliezer. Her maiden name, Alter, means “old” in Yiddish. Both her parents were born in Dorohusk. Her father was a merchant, who travelled through villages and purchased meat for the kosher slaughterhouse; it was then sent to Warsaw. Her mother was a housewife.

“Mama didn't remember her mother very well, as she died when Mama was four years old. Mama had a sister, Zina, who was two years younger. She died of pneumonia after they lost their mother in 1938.”

Mama's memories of her mother's death:

“Mother was sick at home for a long time. One day Father took me to say goodbye to her, but I didn't understand what that meant. It was only when she died, and the house filled with mourning family members and people saying their condolences, while Father sat shiva, that I began to understand.[1] All the family members hugged and took care of Zina and me. We were taken to Aunt Ida's house (she was Mother's sister, and her husband, Avraham, was Father's brother). We lived with our aunt and uncle, and Grandmother Dvora, for about a year. Then Father remarried, to Shoshana, and we went back to live in our own house.”

Mama's memories of her sister's death:

“We walked home from Aunt Ida's house in the freezing winter of 1938. Zina wanted to go to the bathroom, and I undressed her. She became severely chilled and developed pneumonia. Our town did not have a hospital, and Father had to take her to Lublin, the provincial capital. The doctors tried to save her life, but it was no use. She died…”

Mama's first years passed in her family's home. The Polish maid slept on a long bench in the kitchen. The kitchen also contained a dining table. It was illuminated by a window with a hand-sewn curtain. The shelves to the right of the window were covered with embroidered napkins, and held copper pans, skillets, and kettles. Mama remembered the copperware as always gleaming. She slept in the adjoining large room, next to a massive dining table and chairs, that were used on Shabbat and holidays. There was also a leather sofa, where her father would nap on Shabbat. She remembered patting him on the head as he lay there. Her parents' bedroom contained a double bed, veneered in mahogany, as well as a large closet whose door was covered by a large round mirror; Mama used to make faces at herself there. The bedroom also contained a wooden chest topped with a bowl of water and a lovely porcelain pitcher. A room between the large room and the parent's bedroom was always dark, frightening Mama. That room also contained a chest of drawers for storing clothes.

A shack outside the house served as a summer kitchen, as the house would become too hot for cooking. When not used as a kitchen, it was a shed for tools and firewood. Large beams in the yard served the children as balance beams. The yard was fenced, and the roof was thatched. Mama's playmates were her cousins. They played jacks, jump-rope, ball, hopscotch, and marbles with animal vertebrae.

The holidays were celebrated according to tradition. Every major holiday was announced by heightened activity in the home. Children received new clothes for Rosh Hashanah; the family went to services at the synagogue, and apple slices were dipped in honey to signify the wish for a sweet new year. On Sukkot, a sukkah was built, and on Simchat Torah the entire community marched to the synagogue holding flags.[2] A hen would be set aside, for the kapparot ritual.[3] Candles were lit for Hanukah, and the children received gifts of money. On Pesach, the entire family gathered for the Seder, with a special silver goblet designated for the prophet Elijah. The food was Jewish Ashkenazi: dumplings, matza ball soup, gefilte fish, etc. During Shavuot, the floor would be strewn with greenery. On Saturdays, her father would go to the synagogue. When he returned, they would eat baked rolls and drink some hot, sweet milk that had been warmed all night in the oven. As lighting a fire on Shabbat was prohibited, a hired Gentile lit the oven to warm the Shabbat dishes: cholent, noodles, tzimmes, and matza balls.[4] Weddings were held in homes. Klezmer musicians played, and the men danced Hassidic circle dances. Much of the floor space had to be cleared. The pillows and quilts were placed on the parents' bed, providing the children an ideal place to prance around. Those were Mama's memories.

There was a large Jewish community in Dorohusk; most of the people in town were Jewish (Mama remembered that the doctor was a Gentile). Chelm, the provincial capital, also had a large Jewish population.

World War II broke out the day Mama was supposed to start school. Dorohusk was on the border between Poland and Ukraine, on the bank of the Bug River.

[Page 171]

The first bombers that came across the border attacked the Bug's bridges. Mama was in the yard; when they heard the bombs, she ran to the basement, along with Grandmother and the maid. The Germans arrived a few days later, and the family was thrown out of the house. Her father was sent to dig trenches. One day, a German attacked Grandfather with a rifle stock. He then decided to take the family and flee to Russia. He and other male family members such as brothers and uncles crossed the border and began looking for housing and work in Ukraine. When he found a place, he hired a Gentile to guide the family across the border, on sleds (it was winter, and the ground was frozen). Mama was part of the family group, which included my then-pregnant grandmother, Mama's sister, and a 12-year-old cousin. The Gentile helped them across the river, and left them in a field overnight. The Russian border guards took them for Germans, and fired shots in the air. Once they were identified, they were taken to a border guardhouse, where they spent their first night in Russia sleeping on the floor. Grandmother was interrogated all night, as they did not believe she was pregnant. Grandfather came for them in the morning.

They went to the town of Maciejów, where Grandfather found an apartment and work. Most of the Dorohusk family gathered there – uncles, brothers, and Grandmother. That is where Mama's sister Feygeleh (in Hebrew – Tsipora) was born. Grandfather worked for the Russian army as a meat-supply agent (his riding boots are still kept in the stable at Kibbutz HaGoshrim). When they arrived in Maciejów, the Russians made one list of those who wanted to return to Poland after the war, and another list of those who wanted to stay in Russia. Grandfather signed the list for the second group, an act that tagged him as a traitor. As such, he and his entire family were exiled to Siberia.

One night, men came to take the family to the railroad station. They were given a few moments to pack only as much as they could carry. A freight train awaited them at the station. They boarded the train and asked to let Father know urgently. He arrived the next morning and argued with the authorities to let his family off the train or to let him join them. They refused at first, as he was needed at work; eventually, after long argument, they allowed him onto the train. Mama's grandmother begged her son to leave her daughter (Mama) with her and other cousins, but Father decided against the idea, saying “Whatever happens to me happens to my daughter as well.” The family eventually heard that all those who stayed behind were murdered in a lime pit by the Germans.

The train left for Siberia. It arrived at a port after a month's trip with many hardships. The people were then moved on board a boat on the Ob river, which eventually arrived at the Siberian forests. They were then sent in coal cars to a camp that had originally been used for prisoners sentenced to death; its fences had been dismantled only a few days earlier. Conditions in the camp were harsh. The Jews loaded the women and children back onto the coal cars and pushed them to the port. They refused to return to the camp, and were scattered among the local villages.

My family ended up in a village, where they lived in one large room and had a small plot of land to grow potatoes. Eventually, they purchased a cow. Mama began school there, at seven years old; she was placed in second grade, and stayed there for a year and a half. Grandfather worked as a woodchopper, but the work was intolerable at the local temperature (40 C). The villagers were seeking an oven-builder, and Grandfather volunteered. As he had no idea how to do it, he dismantled the oven in our house and rebuilt it.

The family lived there until June 1941. When the Russo-German war broke out, the authorities allowed them to move south. They began travelling. After a long trip with very little food and bitter cold, they reached Tajikistan, in the southern region of the U.S.S.R., and settled in the town of Konibodom. Father was then conscripted into the labor force, and sent to work in a distant uranium mine, where he worked as a foreman. Grandfather built a wooden house with double walls, and filled the space between the walls with gravel, as insulation. The family lived there until the end of the war.

They returned to Poland in 1946, a year after the war's end, and following month-long trip on a freight train, arrived in the region of Silesia. They settled in the city of Wroclaw, which lay in total ruins. Father began to work at fattening geese. The government gave him the zoo, which lay vacant after having been destroyed, and he fattened geese for export. Later, he was granted a plot and established a goose-fattening farm.

[Page 172]

Mama attended a school in Wroclaw where classes were taught in Yiddish. She also became a member of the Zionist youth movement Dror-HeChalutz HaTzair and left with a group for Zionist pioneering training in Bilba.[5]

The group numbered about 40 boys and girls, aged 15-18, with a single leader. They all lived under crowded conditions in a single two-story house. The young people worked and studied at the training farm. They dreamed of leaving for Israel, but the authorities denied them exit permits. The government closed down the Zionist movement at the end of 1949 and prohibited meetings. However, the group continued to meet and study Hebrew in secret. During this period, Grandfather's farm hosted young people from other towns, and supplied them with food, work, and lodging.

In early 1950, some members of the group, including my parents, received exit permits. They arrived in Israel on January 20, 1950, in the Caserta, a ramshackle Italian boat. Most of the passengers were seasick; Mama was one of the few who weren't affected by the motion of the waves. The group went to Kibbutz Na'an, where its members spent about 18 months in a Youth Aliya program. It was the first postwar group to be trained in Zionist pioneering, and the last group of the Dror movement to have such training. The group members joined the Israel army eighteen months later and formed the third pioneering group of Nachal.[6] They were sent to Kibbutz Neve-Ur, where my parents married in April 1953. About two years later, they moved to Kibbutz HaGoshrim with their older daughter Orna, and went on to have three more children - Oded, Amit, and Einat.

I will stop here.

Translator's Footnotes

By Einat Nechushtan, Kibbutz HaGoshrim

(From her 7th-grade research paper “My Family and I”, 1982)

Translated by Yael Chaver

Grandmother Shoshana was born in 1914, to her father Naftali and her mother Chaya. Shoshana was the oldest child in the family, followed by Frida, Charna (now living in Russia) and a young brother, Mordechai.

Her maiden last name was Świnia, Polish for pig – apparently, a nickname added by Gentiles. She was born in Dorohusk, on the banks of the Bug River. Her father worked at a sawmill, cutting wood that he bought from Gentiles. That was his job after World War I, when Grandmother was five or six. The family also owned farm areas, which contributed to the family's income. Her mother was a housewife. After the war, everyone was busy repairing the damage, and doing new construction and development. They worked day and night, guarding their property against theft and other damage by intruders.

They spoke Yiddish at home, but knew Polish and Russian as well. The house she lived in had two wings. Grandmother's uncle lived in one with his family, while she and her family lived in the other wing. The wing consisted of one large and one small room, as well as a corridor that served as a room. Each wing had its own kitchen. There was a courtyard between the two wings of the large house. Grandmother and the other children would play hopscotch, jacks, and cat's cradle. They sang the same songs that Chava Alberstein now sings in Hebrew translation.[1] Great-grandmother sang her lullabies in Yiddish

Grandmother completed seven grades in a Polish elementary school, which was located four km away, across the river. The way was shorter in winter when the frozen lake provided a shortcut. The home maintained Jewish tradition. Shabbat was a day of complete rest: no reading, writing, riding, working, lighting the kitchen fire, etc. A Gentile maid would come that day to cook or warm up food. Each of the holidays had its special dish. At Chanukah, for instance, we ate goose fat, pancakes, and doughnuts (ceramic jars kept the goose fat fresh for Pesach, as well). During the seven-day holiday of Sukkot, we spent time in the Sukkah, and lit the ceremonial candles with a blessing. At the Pesach Seder, the Four Questions weren't asked until the first son was born (this would have been her brother Mordechai). On Purim, the children would go from house to house and hand out the gifts of food.[2]

Shoshana married Eliezer Alter on October 15, 1937. The wedding was at the home of one of her uncles.

The Jewish community of Dorohusk was not large; after all, it was a small town. Chelm was the provincial capital. The towns were scattered; there was one every few kilometers, each with about fifteen Jewish families.[3] Relations with the Gentiles were good until the outbreak of World War II. No Jews remained in Dorohusk after the war; the entire community was exterminated by the Germans, with the assistance of the Poles. The sixty members of Shoshana and Alter's family who lived in Dorohusk were killed during the Holocaust.

[Page 173]

There was a branch of the Zionist Beitar youth movement in Dorohusk. Grandmother joined and was active for several years. It was her first encounter with Zionism. The activities focused on Palestine; the movement trained young Jews for settlement there.

Shoshana and Eliezer Emigrate

The couple applied for exit visas in 1950. People who wanted to move to Israel had to renounce their Polish citizenship. They traveled from Braslav to Warsaw, and on January 17, 1951, boarded a special train for Jews emigrating to Israel.[4] The train took them to the Czechoslovakian border, where the passengers underwent thorough searches to make sure that they had only the right number of suitcases. The passengers continued to Austria and Italy. Everything, including the passengers, was re-examined: bags, suitcases, boxes, and the passengers' bodies, to rule out smuggling. They boarded the rickety old ship Galila, that had carried illegal immigrants to the country during the British Mandate period. The trip took over a week, under very difficult conditions. Finally, arrived at the port of Haifa.

Eliezer's brother, David Yisrael, and his late wife Pnina (of blessed memory) were waiting for them at the port. They took their bags and went to Tel-Aviv, returning to the port several days later to collect the rest of their belongings. They stayed with his brother for 14 months, living in a small room. Then, in 1952, they moved to Moshav Kidron, near Gedera. Grandfather purchased a house on land that was owned by the Jewish Agency, and made improvements to the house with money smuggled out of Poland. They had a small farm, where they raised vegetables and chickens. Grandmother kept house, while Grandfather worked in construction. Once the family was better established, they moved to Rishon LeTziyon, and Grandfather began to work as a subcontractor. He learned to drive at age fifty, and purchased his first car. The family house was built about 25 years ago.

Grandfather died on July 30, 1980.

Translator's Footnotes

Translated by Yael Chaver

The Dorohusk region is in a lower lying area than Dubienka, in Chelm province, Poland, and stretches into the Polesie region. It is on the bank of the Bug River, at the entrance to the Udal' River. There were no heavy battles in the area after the outbreak of World War II in 1939, but the town was constantly bombed by German aircraft because of its railroad station and the two nearby bridges over the river, one carrying the railroad tracks and the other leading to then Polish Ukraine. After Dorohusk was taken by the Germans and the Bug River became the border between Poland and Russia, the Germans began constructing labor camps in the area to build earthworks near the river.

The camp was managed by six Germans. Most of the conscripts lived in crowded wooden barracks, surrounded by barbed wire. The camp was shut down in 1941, and the Jewish prisoners were taken to the Sobibor death camp. At this time, the Germans were carrying out population transfers: locally born Germans were exchanged for Poles from the Poznań„ region.

Germany attacked the U.S.S.R. on June 22, 1941, its forces crossing the Bug River over the bridges in the Dorohusk region.[1] Soviet prisoners were soon sent through Dorohusk to POW camps in Chelm; many of them were killed en route, before arriving at the camps. The Germans began intensifying their persecution of Jews in 1942. The four hundred Jews of the Siewierz Ghetto were transferred to the Sobibor death camp. Jews were hunted and murdered at random. In May 1942 five Jews were murdered in Ostrowo, eleven in the village of Pogrnoczo, and six in the village of Turka, as well as in other locations around Dorohusk, including Turka, Brzeżno, Sieswierz, Chosnana, and Bradiszczew.[2] There were 450 Jews in Sieswierz alone, all of whom were killed after being sent to Sobibor.

[Page 174]

|

|

|

|

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dubienka, Poland

Dubienka, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 14 Sep 2025 by JH