|

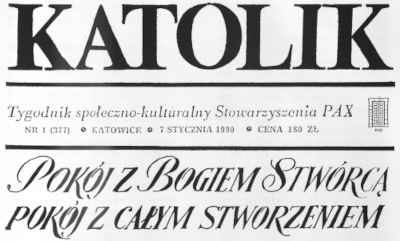

| “KATOLIK – WEEKLY SOCIAL-CULTURAL ASSOCIATIONS PAX”

Katowice, January 7, 1990 A Place for God's Creatures, A Place for All Creatures |

|

|

[Page 122]

Skryhicin

51°00' 23°55'

(Skryhiczyn, Poland)

(Hebrew and Yiddish)

[Page 123]

by Gershon Shachar

Translated by Yael Chaver

Much can be said about the village of Skryhicin. Any Polish village contains primitive peasants who are usually illiterate. But Skryhicin included a special Jewish community, whose members were pious, scholarly, and descendants of Hasidic leaders. They possessed all the best features: religious study, work, Zionism, and good deeds. They were very unusual for Polish Jews. Most Polish Jews were not farmers; Polish law prohibited selling land to Jews. But the brothers Shmu'el and Chayim Rothenburg, of the Ger Hasidic group, were able to purchase an entire estate in Skryhicin. Naturally, this involved some kind of ruse concerning the government.[1] The brothers presented their Gentile shepherd to the authorities as the purchaser; as he could not sign his name, he dipped his thumb into ink and pressed it onto the document. The town hall clerks smiled at the sight. The Yiddish author Y. Y. Trunk mentions the two Rothenburg brothers, as “Two stars in the skies of Jewish Poland.”[2] They created an impressive economic ‘empire’ on that land, which included fields, pastures, forests, and a sawmill to treat the lumber from their forests. They also possessed horses, cows, and other livestock.

This was quite remarkable, because most Polish Jews were scholars who studied the sacred books constantly. They did not work, certainly not as farmers. But here, in Skryhicin, a special community formed. As Y. Y. Trunk writes, the village looked like a village in a future the Land of Israel, after the coming of the Messiah, where the birdsong was that of the High Holiday prayers, and deer studied Talmud.[3] I remember how proud the Jews of Dubienka were of their neighboring community. Skryhicin was considered Paradise, and the members of its Jewish community were angels. They were economically well-off, and always ready to help those in need. We in Dubienka knew how generous they were. They helped when needed, such as arranging the wedding of a poor couple, or sending a sick person to Warsaw for surgery. Two Dubienka Jews would volunteer to walk to Skryhicin, which always responded well. Beggars passing by knew to stop there, and always left carrying gifts.

Everyone remembers Rivkeleh, Shmuel's wife, who would load a wagon with milk products, fruit and vegetables every Thursday, and send it to Dubienka to supply the poor for Shabbat. Yes, there is much to say about the village of Skryhicin; everyone had good memories of it and its Jews. The pious, scholarly Rabbi Menachem Sirkis wrote about the community at length in his book, Ish Ha-Emunah (Man of Faith).[4] He knew its entire history and describes it reverently. Y. Y. Trunk describes them lovingly as “Jewish landowners,” and provides details of their interesting ways and customs, as well as their weddings and celebrations.

A Polish book by Irena Kowalski and Ida Merżan about their beloved village mentions the Rothenburgs and the Jews who lived there. All the Warsaw Yiddish and Polish newspapers were enthusiastic about the book, and wondered why the village had never become famous: “How has no one heard of such a legendary village?” People sought terms to describe the village and suggested “Arcadia” or “Anatevka on the River Bug”.[5] They thought that the village would supply good material for a movie, like Bashevis Singer's character Chava.[6] Unfortunately, we cannot afford to publish that book in a Hebrew translation; we also had trouble raising money for this Yizkor book, which is finally seeing the light of day. Ida Merżan (of the Rothenburg family) and Irena Kowalski (of the Prywes family) will never forget the

[Page 124]

dear Skryhicin community where they were born and lived. The people were so polite and generous, and always willing to help others. The two women decided to write and publish a book in Polish to commemorate the community, so that their children and grandchildren, and all the world's Jews would know about the beloved Skryhicin community. Ida Merżan died before the book was published, and the press notices expressed their regret that she did not live to see this fascinating book in print.

The village produced many fervent Zionists who left their rich families and emigrated to Palestine when it was still racked by malaria. It was the Szidlowskys and Rothenburgs who founded the kibbutz settlements in the Jordan Valley; they are the subjects of several books.

Aharon Szidlowsky (of blessed memory) was one of the founders of Kvutzat Kinneret, in the Jordan Valley, in 1912 – the very first Jewish settlement along the Jordan. The surroundings were bare and dry. A book about him is to be published soon, which will detail the accomplishment that he and his determined pioneering friends achieved: creating a model kibbutz.

I immigrated to the Land of Israel in 1939. During our training period abroad, we resolved to request permission to establish a new kibbutz in the same area. We settled in the Beth She'an Valley, with Kibbutz Ma'oz Chayim; the founders had been there for a year. I'm very familiar with this period, as I experienced it myself. Establishing a settlement was complicated: the area was bare, the climate was hard to deal with – temperatures reached 40 degrees Centigrade – and malaria was widespread. Looking at the Jordan Valley today, with its many flourishing settlements, from Tirat Tzvi and Ma'oz Chayim to the Sea of Galilee, I must say I am very proud. I tell the story of the Jewish pioneers who settled the area: the Szidlowskys and Rothenburgs of Skryhicin, and others.

This book completes their story.

Translator's Footnotes

By Rabbi Eliezer Sirkis (of blessed memory) in his book Ish Ha-Emunah[1]

Translated by Yael Chaver

In 1879, my grandfather Mordechai Kalmen Rothenburg purchased the Skryhiczyn estate from a Polish landowner who had lost his property. It was 5 km from the old Polish town of Dubienka, and about 20 km from Dorohusk train station. Grandfather Mordechai Kalmen and his wife, grandmother Itta-Reyzl, worked hard to make their land profitable.

Grandfather came from a great lineage. He was a descendant of the great scholar Meir of Rothenburg, known as Maharam (1215-1293); the latter was the teacher of Asher ben Jehiel, the eminent rabbi and Talmudist (1250-1327) best known for his abstract of Talmudic law. Grandfather's father, Rabbi Ya'akov Yosef, was the brother of the first leader of Ger Hassidism, Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Alter (who changed his name due to Czarist persecution) and of Moshe Chayim and Aharon Eliyahu Rothenburg. Their father, Yisra'el Rothenburg, the leader of the Ger Hassidic group, was the son of Rabbi Mordechai Rothenburg, head of the rabbinic courts of Magnuszew, Żelechów, and elsewhere; he was considered a close associate of the Maggid Yisra'el of Kozienice. He also fathered eight rabbis. Rabbi Mordechai's brother was Rabbi Moshe Rothenburg, head of the rabbinical court of Wlodawa, who compiled She'elot U-Teshuvot Maharam ha'Acharonim (Recent Responsa of Maharam). In section 14 of Even Ha-Ezer he acknowledged that he was following in the footsteps of his illustrious grandfather.[2] Grandmother Chaya-Sarah (the wife of Rabbi Yisra'el Rothenburg) was also of fine lineage, going back to Rabbi Natan Shapiro, writer of Megaleh Amukot (Revealer of Depths).[3]

The women of Skryhiczyn had many children. Not a month went by without a circumcision, or a kiddush in honor of a newborn girl. Women who had stopped giving birth complained to their female relatives. Some new mothers breast-fed their children for two years or more, and even taught their babies to say the blessing over breast milk.

The children on the estate suffered from many diseases for which there was no cure at the time, such as measles, scarlet fever, etc. Families lost as many as half of their children, sometimes even more (as was the case in the family of Grandfather, Mordechai

[Page 125]

Kalman, in which only four out of seventeen survived). If that hadn't happened, the village would have quickly grown into a town…

The main source of livelihood was the forest, where trees were felled and sent down the Bug River to the port of Danzig. Grandfather Mordechai Kalman was, of course, a disciple of the Hassidic rabbi Mendel of Kotsk and of his uncle Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Alter (Rothenburg), founder of the Ger Hassidic group.[4] He sometimes visited Rabbi Yitzchak of Niesuchojeze, who was famous as a miracle worker, and would “buy” the snow or water of the Bug River, to speed the lumber's journey to the Danzig. One year, he forgot to do this, and all the rafts that carried his lumber fell apart, losing all the logs. Grandfather was also very hospitable and contributed much to charitable causes. When Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Alter was enroute to visit Rabbi Yisro'el of Ryzhin and planned to stay in Hrubieszow, Grandfather came and asked him to spend Shabbat in Dubienka.[5] At first, Rabbi Meir Alter refused, saying that the Hassids of Hrubieszow weren't serious enough. However, when Grandfather's brother Rabbi Pintche of Pilts (Pilica), who was with Rabbi Meir Alter, spoke with the Rabbi, he agreed.[6]

Grandfather Mordechai Kalman and Grandmother Itta Reyzl had many children (sixteen or eighteen), most of whom died young. One of them, Yisr'ael, who was engaged to be married, is supposed to have argued with the Angel of Death, but of course lost. Two sons (Shmuel Tzvi and Chayim), and two daughters (Bluma and Zlata) survived. According to family lore, Grandfather went to his uncle, Rabbi Yitzchok Meir Alter of Ger, requesting a groom for Zlata from among his uncle's orphaned grandchildren who were living with him. Rabbi Meir Alter pointed out two boys, Aryeh-Leyb – the son of the late Rabbi Avraham Mordechai (later, author of Sefat Emet),[7] -- and Simcha Bunem Yustman. Grandfather preferred Simcha Bunem, who was calmer and less mischievous. It should be noted that both boys were around thirteen. Zlata died during her father's lifetime, and left a young daughter, Leya. Mordechai Kalman's other daughter, Bluma, married Baruch Kaminer, the son of Rabbi Yudl Kaminer (author of Degel Yehuda), who was connected by marriage with Avraham Mordechai.[8]

Grandfather Mordechai Kalman died at age 56, on October 8, 1877. When discussions of the inheritance began, Shmuel Tzvi demanded that it be divided according to religious rules; the two sons would share, and the orphan Leya would receive one-tenth of the inheritance upon her marriage. However, Rabbi Baruch Kaminer (speaking for his wife Bluma) and Rabbi Simcha Bunem Yustman (speaking for his daughter Leya) demanded that the inheritance be divided into equal parts, according to local rules of the time. Thanks to the demands of Grandmother Itta Reyzl, who had run the estate jointly with her husband, and continued to do so after his death, a religious proceeding was held by two of Grandfather's brothers: Rabbi Pinchas Eliyahu of Pilica, and Rabbi Avraham Chayim Reuven Rothenburg, Rabbi of Wodzisław. They reached their decision four months later.

Translator's Footnotes

By From Ish Ha-Emunah by Rabbi Eliezer Sirkis (of blessed memory)

Translated by Yael Chaver

Weddings were always major events in the village, whose people counted time according to these occasions. Each new count would start with a new wedding.

The guests included men and women from the entire area, poor people as well as beggars. Long tables, made of boards from the Skryhiczyn sawmill, were set up, to accommodate the entire population of the village as well as guests. People would sleep wherever they found a place, and stay throughout the seven days of festivities. Once, robbers in tattered clothing sneaked in among the legitimate beggars at one wedding. At the height of the celebration, they pulled out their revolvers and began robbing whatever they could. The men had to give up their watches and money, and the women had to surrender their rings, earrings, and whatever jewelry they had, screaming loudly. Luckily, there were no fatalities. Women who were able to conceal some jewelry were considered brave and lucky. After the weeklong festivities, the families of the married couple would set bowls full of half-ruble coins on the table, and the poor would wait their turn at the bowls.

The wedding of Rabbi Eliezer and Chaya, in the month of Sivan 1898 was lavish and well-attended.

[Page 126]

The bride's entire family was present, including the sons of the Ger Rebbe, who were both family members and honored guess. Rabbi Chayim's uncles were present – Rabbi Pinchas Eliyahu Rothenburg, Rabbi of Pilice, who attracted attention with his long white beard and impressive posture; and his brother, Rabbi Chayim Reuven Rothenburg of Wodzislaw. Both the latter came with their sons and their families; the other two brothers of Mordechai Kalman – Rabbi Yisro'el (head of the Horodlo rabbinical court) and Rabbi Efrayim Fishl, the father of Rabbi Simcha Menachem Rothenburg (head of the Hrubieszow rabbinical court) – also came.

Rabbi Shlomo and his wife, Sara Sirkis, were accompanied by his father-in-law Rabbi Mordechai Kalman and his wife, Miriam, and their families. The groom's rabbi, Rabbi Yechiel Elberg came with his son, Rabbi Natan (the groom's friend). Two of Rabbi Shlomo's close friends – who had introduced him to Ger Hassidism – Rabbi Note Hinsdorf and Rabbi Note Pozner. Rabbi Chayim Rothenburg enjoyed talking with Rabbi Note Hinsdorf, who wrote rabbinical and Hassidic works as well as secular and liturgical poetry (and corresponded with the Hassidic leader Rabbi Wolf Landoy of Stryków). He already knew Rabbi Leybush Pozner, who had been involved in his match with Rabbi Shlomo's family. Rabbi Binem Yustman, formerly the brother-in-law of Rabbi Chayim and the grandson of Rabbi Yitzchok Meir Alter, came, with some of the important Hassidim. Several important Hassidim came from Warsaw.

Of course, there was no shortage of traditional entertainers (badkhens) and musicians who had come from Warsaw to amuse the guests. Lodgings were something of a problem, but solutions were found. Some people were taken to Dubienka by carriage.

When Rabbi Shlomo arrived in Skryhiczyn, he followed the advice of friends and went to visit his father-in-law's older brother, Shmuel Rothenburg, who was lying down with a book. When the latter heard about the visitor from Zgierz, he did not rise to greet his guest, but held out his hand and said, “Sholem Aleichem, relative!” Rabbi Shlomo remembered the slight all his life.

After the chuppah, while the family members were enjoying the best treats that Skryhiczyn could offer, the chief badkhen began reciting amusing rhymes. However, when he switched to religious topics, inventing bits of midrash and religious questions that he answered humorously, the elderly Rabbi Pintche stood up and announced, shaking with rage, “Listen, badkhen! I was patient as long as you were telling jokes – after all, that's your living. But now that you're joking about Torah matters, I must tell you to leave those topics to me!”

The festivities lasted for a week. New guests arrived daily. Meat from the farm and fish from the Bug River were served, and dairy products were plentiful. The family members were beside themselves with joy, especially the elderly Rabbi Mordechai Kalman and his wife Miriam. They gave the young couple lavish presents as well as hundreds of rubles.

After celebrating for a week, all the family members left, and for the first time in his life Eliezer was separated from his family and friends. He was sad, although his father-in-law and family did their best to raise his spirits. However, he soon made new friends, such as his brother-in-law Mordechai Kalman Rothenburg, with whom he had exchanged letters, and who was about to marry Henye Rachel, the daughter of his uncle Rabbi Shmuel. Mordechai Kellman, or Motl, as he was called, was strongly built, always in a good mood, and with a good sense of humor; he often amused his parents and others nearby. He was a scholar who punned on the meaning of biblical phrases. Eliezer became friends with Leybl (the son of Moshe Yerucham, son of Rabbi Mendl of Kotsk) who was married to Leya, Rabbi Chayim Rothenburg's niece; Leybl was a scholar who lived in Skryhiczyn all his life.

Besides studying in the classes arranged by his father-in-law, Eliezer and his brother-in-law Motl studied with Leybl, and his uncle Rabbi Pintche of Pilitsa, who visited Skryhiczyn often in connection with the matter of the inheritance.

By Chana Rotenberg-Vintl

Translated by Yael Chaver

My brother, Pinchas Rothenburg, has asked me to write the history of the Skryhiczyn estate, which belonged to two brothers (our grandfathers) – Shmuel Zvi and Chayim Rothenburg (of blessed memory). My sources are stories from Grandmother Rivkeleh (the wife of Shmuel Zvi Rothenburg), Grandfather Chayim Rothenburg, my mother Rachel Rothenburg, our father Mordechai Kalman Rothenburg, our uncle Mordechai Rothenburg (my mother's brother), and my own childhood memories.

By Chana Rotenberg-Vintl

Translated by Yael Chaver

For the members of my family who were born and grew up here, in our own country,

to help them know “Joseph” –

Yosef Rothenburg,

father of Mordechai Kalman (Kalonymos),

father of Shmuel Tzvi and Chayim Rothenburg.[1]

Translator's Footnote

By Chana Rotenberg-Vintl,

Granddaughter of Shmuel and Chayim Rothenburg

Translated by Yael Chaver

The estate lies on the bank of the Bug River, in the province of Lublin, five kilometers from the town of Dubienka; it covered an area of 3630 morgen.[1] It included forests, fields, lakes, pastures, etc. It was the property of the brothers Shmuel Tzvi and Chayim Rothenburg, who were natives of Dubienka. Their mother, Itta Reyzl (née Rapoport), born in Dubienka, was married to Mordechai Kalman Rothenburg. I do not know where he was born; possibly in Volhynia, across the Bug. That might explain the unusual version of Yiddish they used.

Mordechai Kalman Rothenburg was a scholar as well as a wealthy lumber merchant. He built the large, two-story synagogue in Dubienka, and stone buildings. He died young, at age 45, of diabetes. His wife, Itta-Reyzl, managed the forest business. Aided by her oldest son, Shmuel, she would dispatch rafts with lumber down the Bug River to the port of Danzig. She knew the owners of the large estates in the area, as well as Count Potocki (who was friendly to Jews), and others.[2]

At the time, the Skryhiczyn estate was the property of a German man who had been widowed and whose only daughter had been killed by lightning. He set up a booth containing a statue that commemorated his daughter, and kept it across from his office. Itta Reyzl, who would visit his office, advised him to sell the estate and return to Germany; life among his countrymen would be a consolation.

She purchased the estate and moved to Skryhiczyn with her two sons; Shmuel was then 24 and Chayim was 12. Grandfather Shmuel established a sawmill, while his mother bought forest property. They began floating rafts to Danzig. The area contained many forests, inhabited by bears and wolves; the forests lined the road from Dubienka to Grandfather's house.

Grandfather Shmuel and his family lived in the German's mansion. Shmuel was married at age 15 to Rivkeleh Kerl (aged 13), the only daughter of Yosef Kerl of Warsaw, and had fathered children. Shmuel Tzvi had the booth with the statue of the girl removed and set up outside his courtyard. Eventually, it became known as the Holy Virgin of the Skryhiczyn peasants. They bowed and prayed to it, and decorated it on holidays, not noticing that the booth was surmounted by a rooster weathervane rather than a cross…

Grandmother established a large sawmill, which was managed by an expert from Germany. The peasants worked at the sawmill and built rafts to carry logs down the Bug to Danzig. Rafts were built until 1914, when World War I broke out. When Grandmother Itta Reyzl purchased the estate, the peasants were serfs – freed slaves, who would work for the landowners for free one month each year. Grandfather Shmuel began paying them for that one month. The buildings at the roadside opposite Grandfather's property were taverns that also produced brandy. The peasants spent their money at the tavern, and the money was added to the landowner's income. This was common practice in the region. However, Grandfather closed the taverns and used the buildings as housing for workers who carried out different jobs on the estate, especially artisans such as tinsmiths, carpentry, shoemaking, leather-working, and day- and night-guards.

[Page 128]

He made sure that these artisans were Jews in sufficient numbers for community prayers.

Grandfather Shmuel was extremely wealthy. He built houses in Hrubieszow for his poor relatives, who then opened various businesses such as shops and hotels. Both grandfathers gave lavishly to charity. A special clerk sent donations twice a year, before Passover (Pesach) and Sukkot. My mother told me that Grandfather's sons once asked him why he was donating so much money. He responded that he received far more than he gave. Once, his sons asked him why he gave clothing as well as money to a poor beggar, and only a bit of money to an emissary from a Jewish institution. He told them that rabbis and emissaries were usually given handsome donations, but solitary beggars were usually turned away.

As a child, I heard much about Grandfather's wisdom and scholarly expertise. After the death of Rabbi Yehuda Leib Alter, Grandfather was asked to replace him as the head of the Ger Hassidic group. He refused. Great rabbis came from far away and tried to convince him, but to no avail. As he said, “People know that I am very wealthy and charitable, but they don't know that I'm also very stubborn.”

I remember that once, when I was a child, Father took me to the Bug River. I walked onto a raft and went into the two-room shack that stood on top of the raft. One room contained beds, and the other had a table and benches. There were two Gentiles on the raft, and two Jews in the shack: Sha'ul Leyzer Dantsiger of Dubienka, and the bookkeeper. At Father's request, they floated the raft for a bit. I really enjoyed the demonstration.

Grandfather Shmuel also built the large bridge at the entrance to Dubienka. For many years, anyone entering Dubienka had to pay a toll. The toll-takers were two Jews of Dubienka. The bridge to Horodlo also belonged to Grandfather; it was managed by a distant relative, Chayim Froyim.

Grandmother Itta Reyzl ran the businesses until she was too old to do so. My mother spoke of her very lovingly. Naturally, she did not like Grandmother Blumtshe, and built her a place of her own that was connected to Chayim's house. Eventually Aunt Leya Morgenshtern lived there. She was Itta Reyzl's granddaughter, and had been orphaned when her mother, Itta-Reyzl's daughter Leya, had died while giving birth to her; the baby had grown up in Itta Reyzl's home. Little Leya was Chayim's age. They were close friends all their lives, and died on the same day.

Shmuel and Rivkeleh's house was always full of grandchildren. Their sons and daughters had long since left home, but one returned and took on the management of the estate – Uncle Mordechai, my mother's brother. He set the tone in the village. Under his management, the estate raised horses for the Russian army, as well as calves and cows. Mendele Dantsiger managed the small farm. Horses were raised on the large ranch, while the small farm contained a dairy that produced cheeses, milk, and cream for private use and donations to the poor of Dubienka. Let me also mention Grandmother Rivkeleh, who grew fruit and vegetables, and would send over a wagonful of produce to the poor of Dubienka every Thursday, for Shabbat.

Life in Skryhiczyn went on in this placid manner until 1920. The civil war that broke out in Russia that year led to the formation of gangs of robbers and murderers that also caused a shock in Skryhiczyn. A gang of robbers arrived in Skryhiczyn while there were guests from all over Poland. It was shortly after the wedding of one of Grandfather Shmuel's daughters. Skryhiczyn guests had to be driven from the railroad station in Dorohusk, which was about 15 kilometers away. When they sent a carriage to the station to bring Menachem Privas, eleven robbers boarded the carriage as it was coming back. They reached Grandfather Chayim's house, filled their sack with money and diamonds, and continued to Shmuel's house, where there was a strongbox that held charitable donations. They demanded that he open the box, but he refused, telling them that they had robbed enough, that the box contained very little money, and that he, as an unpaid watchman, was not responsible.[3] Nevertheless, he agreed to open the box. They decided to hang him. At the last minute, one of the robbers, a Jew saved him from that fate. Day had dawned in the meantime, and the robbers left, saying, “Continue making money; we'll be back.” They left, and went to the sawmill, which they tried to rob

[Page 129]

and burn down. The German manager was able to photograph the robbers, who were later found and identified thanks to his photo. Many objects were returned, especially those that were marked.

The German manager was in Lublin in 1924, saw the Jew who had been among the robbers, and slapped him twice. The Jew died on the spot. The German, who was well-muscled, was exonerated. The manager visited us that same year, and everyone reminisced about the robbery. Our parents were abroad during the robbery. The writer Y. Y. Trunk, who was Aunt Leya's brother-in-law, mentions the Skryhiczyn estate and the brothers Shmuel and Chayim Rothenburg, describing them as bright stars in the skies of the Jews of Poland.[4]

The other shock was the outbreak of World War I, in 1914. Mother and we children fled to Odessa, while Grandfather, his wife, and grandchildren, stayed on the estate, as did our father. Grandfather Chayim and his family fled to Warsaw. We returned six months later, when Skryhiczyn was no longer on the front line; Grandfather Shmuel wanted us back. But after only six months, we left again on horse-drawn wagons and reached Kyiv. We stayed for a time in a hotel near the city. Grandfathers and grandmothers were the only ones who remained in Kyiv, and lived with Gitl Brodsky. They all had permits to live in Kyiv, but we did not, and went to Odessa.

We returned to Skryhiczyn in 1918, at the end of the war. Poland was granted “independence.” However, we came back without Grandfather Shmuel; he had died in Odessa and was buried there. Back in Skryhiczyn, we found the estate destroyed and Grandfather's house burned to the ground. We had not yet recovered from traveling, when war broke out between the Poles and Russian Bolsheviks. We were refugees once again, this time without horses or money, and walked to Chelm.

Let me return to 1914. When the war broke out, the Czarist government confiscated 1,500 estate horses and 500 cows and gave us checks as compensation. While we were in Odessa, before the Bolshevik revolution, the Russian Treasury sent us monthly payments. For four years, we five families with children lived in Odessa. When the Bolshevik revolution began, the new government refused to honor Czarist checks, and we lost a great deal of money. It was time to go home. Skryhiczyn was under Austrian rule, and the top command was located in Grandfather Chayim's house. The high commander was Jewish; when he learned that the estate was owned by a Jew, he photographed every item and made sure that there would be no disturbances on the estate.

As a very young child, I heard Grandfather Shmuel every morning studying the Torah with his older grandchildren, while Grandfather Chayim's sons-in-law studied with teachers. During the summer, they learned in the fruit orchard, and the Torah chants mingled with birdsong. Grandfather Shmuel's house was modest, whereas Grandfather Chayim's house was lavish, with modern furniture; they even had a gramophone that they would play in the evenings. Sometimes Grandmother Blumtshe invited us for the evening meal, during which the aunts would play records.

I still remember the elaborate wedding of Aunt Masha Eisenberg, that lasted a full week. A sumptuous meal, accompanied by musicians and dancing. was prepared for the town's indigents. Secret gifts were given, and the bride danced with the poor. I was told that Aunt Leya Privas's wedding was even more elaborate. Grandfather Chayim liked to have opulent weddings for his daughters. He would invite the entire staff of the “Paris” hotel from Warsaw, including the cook and all the waiters with their equipment. The wedding festivities lasted a week. The installation of a new Torah scroll in the synagogue our father built was another major occasion, as was the Bar-Mitzvah celebration for Yossele, the son of Uncle Mordechai and Aunt Sheyndl Rotenberg.

I also remember the magnificent wedding of Shifra Rosset; the event lasted until dawn. Clerks, laborers, and peasants all joined in the celebration. Carriage owners in the nearby area would send their beautiful carriages to bring the guests, and the drivers wore their liveries. I remember Grandmother Blumtshe's driver in his livery when he took her for a drive; the carriage, with lamps burning on both sides, was drawn by four horses.

Grandfather Shmuel and Grandmother Itta Reyzl purchased the estate in spite of the prohibition against selling land to Jews. The official owner was Stach, a seven-year-old shepherd boy who had been raised by Grandmother. He signed the documents with a fingerprint, not realizing how rich he had become. He remained illiterate all his life and was a drunkard. Once Poland was independent, the law prohibiting land sales to Jews was revoked, and Stach became the night raft watchman.

[Page 130]

He studied carpentry during the days. As he spent all his money on liquor, he was the only peasant without any property. His son, known as Balali, was a complete idiot, who destroyed Grandmother Blumtshe's beautiful furniture in 1914. When the authorities came to check out the damage done by Balali and other ruffians, they wept at the sight; they knew the house before it was damaged. The contents were insured by three insurance companies.

I'd like to mention that before 1905 Grandfather had several trusted workers who helped him manage his forestry enterprise. One of them was Bentsyeh Zeiger, who was based at the sawmill and did the bookkeeping for that business. Another was Yosef Vinakur who, together with his son Moshe, ran the cow and dairy business on the large ranch. Shmuel-Leyzer Dantsiger of Dubienka was in charge of sending the rafts downriver. Grandfather Shmuel gave the orders.

After the robbery, Grandfather became sick, for the first time in his life, and began devoting all his time to religious study. His son Mordechai, who was famous for bravery, took charge of the forests. He would ride out alone at night to inspect the forests and their guards. One night, he was assaulted by thieves, and was gravely injured. Management of the fields as well as bookkeeping were entrusted to my father, Mordechai Rothenburg. Mendele Dantsiger headed the dairy operation at the small ranch. He would ring the bell three times a day, and the women who did the milking would come to the cowbarn.

The cream separator was already in use at the time. All the produce of the small farm were for the use of Chayim's and Shmuel Rothenburg's families. The large farm sold its products commercially. Father introduced the agricultural machines of the time into the field work, such as the thresher and automatic reapers. I remember the owners of nearby farms coming to observe the machines.

Following 1905, an alarm bell was set up between the homes of Shmuel and Chayim; later, telephones were installed. We and Uncle Mordechai on the small farm had telephones; so did the large farm and the sawmill. One ring was for us, two for Uncle Mordechai, three for the large farm, and four for the sawmill. We also possessed many firearms; Father was a fine marksman, besides being an expert horseback rider and swimmer. The Gentiles constantly complimented him and Uncle Mordechai.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the telephones were dismantled, the weapons were collected and sunk into the Bug, and the alarm bell was taken down for fear that provocateurs would report it as a means of contacting the enemy. The retreating Russian army burned down the large ranch as well as the sawmill and the entire village. The peasants fled, and everything was destroyed. Skryhiczyn ceased to flourish. Uncle Shmuel, Grandmother, and all the children couldn't leave in time, and stayed behind. Some of the grandchildren, such as Noakh Horovitz, were too young.

Grandfather Chayim and his family left for Warsaw. Mother and we children fled to Odessa, while Father stayed behind to continue his job. The front line was in Lipnik. The Russians alternately advanced and retreated. There was no chance to bury the dead. A cholera epidemic broke out, and many of the village residents who had not left died; Father also fell ill. The Gentiles cared for him until he recovered, and then left for Warsaw to complete his convalescence. Life in Skryhiczyn thrived again, and continued to do so until the ultimate devastation.

The estate hummed along, and Grandfather Shmuel's house became a place of constant religious learning. Grandfather studied with his older grandsons, while the younger ones studied with Yosef Shmuel the melamed in a schoolroom next to Uncle Mordechai's house. Uncle's son Yossele also studied with Yosef Shmuel. Grandfather Chayim hired teachers for the unmarried girls, and a music teacher who taught Father to read notes. Father would climb up to the attic in Grandfather's house and practice singing with this teacher for hours. We children called the teacher “Singer,” as we never learned his real name.

Grandfather Chayim's house employed male and female servants, and Grandmother also ran our household efficiently. We spent all day at the cheyder. Noakh complained that the melamed was singling him out for physical punishment, and Grandmother Rivkeleh moved the cheyder to the room that was reserved for the sukkah. We were protected from then on; Grandmother would peek in from time to time, to make sure everything was all right. The melamed was irritable, and constantly in a bad mood. We hated him.

One day, our lives changed. A woman kindergarten teacher arrived, who taught us in Hebrew; there was also a Russian teacher. We stopped spending all day in the cheyder, and started to have fun; we mounted skits, learned to ice-skate and play croquet, and took walks in the forest to gather mushrooms and berries.

[Page 131]

A special Bible teacher named Shlomo Lev came from Dubienka twice a week to teach us. All this ended in 1914, when the war broke out. We did not grasp the tragedy of war. We were happy when our hated teacher was conscripted into the army, and we were released from studying with him.

Let me return to Grandmother Itta Reyzl. Grandfather Chayim told me that she was successful as a businesswoman, but unlucky in her family life. She gave birth to twelve children, most of whom died young. One of her sons was older than Grandfather Chayim and lived in Kyiv. He married a woman from the Brodsky family, who owned a sugar manufacturing enterprise.[5] As I recall, his name was Aharon; he was handsome and a great Torah scholar, but died young, at age 27. Grandfather Chayim told me that the Brodskys came to Skryhiczyn for the wedding in gilded carriages, drawn by horses in golden shoes; their attendants were in livery. Aharon's wife never remarried. In 1915, my grandfathers stayed with their sister-in-law in Kyiv before they went to Odessa. The sister-in-law's name was Gitl Brodsky. Grandfather Chayim's wedding was on the estate, because his mother couldn't travel.

Our mother told us about the death of Grandmother Itta Reyzl. It was on the eve of Yom Kippur. Grandmother lit the holiday candles, kissed the children and grandchildren who were on their way to prayers, and asked them to go to the synagogue in Grandfather Shmuel's house. When they returned, they found her dead on the sofa. When the news of her death spread, all the shops in Dubienka, Hrubieszow, Lublin, Zamość, and even Warsaw, closed. The entire Jewish community of Warsaw mourned for Itta Reyzl Rapoport Rothenburg.

Grandmother Blumtshe Vilner-Rapoport was the great-granddaughter of the Gaon of Vilna. She grew up and went to school in Warsaw. It was she who occasionally travelled with Grandfather Chayim from the small town to the metropolis, and to spas in other countries. Grandmother Blumtshe was educated; she had graduated from the first women's' school in Warsaw, headed by Madame Peproczka.[6] She knew German, French, and English, and could play the piano, but Grandfather Shmuel did not permit her to bring the piano to Skryhiczyn. When she had lived in Warsaw, she attended balls given by Russian aristocracy; she told me that she had danced with the Russian governor. When she arrived in Skryhiczyn, she could hardly use the prayerbook. Over the years, she was influenced by life in the village and the Ger Hassidic group, yet never blended in. All the village laborers called her “the lady from Warsaw.” Grandmother Rivkeleh, on the other hand, who was also from Warsaw, was known as “our grandmother.”

In 1915, when we were refugees in Odessa, Grandfather Shmuel and Grandmother Rivkeleh stayed with their daughter, Masha Halperin. Her apartment was lavish, with central heating and hot water. Aunt Masha and her husband greeted the refugees with warm hospitality and great respect. Sadly, Grandfather Shmuel died shortly after he arrived in Odessa, at age 67. I have never forgotten the mourning that enveloped our families, or his large funeral. Only men were allowed to participate; according to local custom, women could not join in funerals. Our mother was overcome by grief and became very ill; she spent a month in a sanatorium.

Our family lived for a while on Kuznitznaya St. and then moved to 40 Uspenskaya St. Aunt Pesla and Aunt Blumtshe, with their children, lived on Malaya Arnautskaya St., while Grandfather Chayim, his family, and Aunt Leyaleh Morgensztern and her husband lived on Bolshaya Arnautskaya St. The war dragged on. My sisters Itta and Bella and I, started studying at the Zhabotinskaya-Kopp high school, and my two younger sisters, Gitl and Leya, entered the Hebrew-language kindergarten of Yechiel Heilprin.

The revolution broke out in Russia, the Czar was deposed, and Kerensky came to power. However, after six happy months, a civil war began between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. This was followed by German occupation.

As long as we were in Odessa, the Czarist government paid us for war losses to the estate, in compensation for having confiscated horses and cows from Skryhiczyn, and other damages. Father and Avraham Gershtenkorn (the bookkeeper) would travel to Petrograd once a month to receive payments. When

[Page 132]

the civil war began, the Bolsheviks did not honor the promises of the Czarist regime. We then decided to return home. After a long trip, we reached the Polish-Russian border, only to wait for a long time before we could actually cross the border. While we were in the border town of Lutsk, an Austrian officer told us that he had come from Skryhiczyn. He was Jewish, and when he heard that the estate was Jewish property, he guarded it as closely as he could. He showed us the pictures he had taken of the forests and the buildings, and said that everything was fine and nothing was missing.

Skryhiczyn was now under Austrian control. When we arrived in 1918, there were barely any residents in the village. Grandfather Shmuel's house was burned down, but his two daughters, Sara Blass and Leya Privas, lived there with their children. There were also some of Grandfather's children and grandchildren.

We had barely gotten settled and put the farm in order, when Poland gained independence. A new war broke out, between Poland and the Bolsheviks. Once again, we fled to Chelm. Grandfather Chayim and his family were able to escape to Warsaw. When the war was over, Skryhiczyn remained in Polish territory. We returned home. There was no money to live on, or revive the estate. There was very little or no income from the properties in Warsaw. Grandfather Shmuel's heirs decided to divide the estate between themselves and Grandfather Chayim Rothenburg. One of the grandchildren, Yechiel Mintzberg, who was wealthy, divided the estate between the heirs. I'd like to note that the division was carried out peacefully, with no quarrels, and led to the formation of several farms in Skryhiczyn.

Our parents were born on the same day, the holiday of Shavuot. Mother was twelve hours older than Father. They were betrothed the day they were born. Father was the only son among several girls; Grandfather Chayim and Grandmother Blumtshe lost two sons. Grandfather Shmuel made sure that the two children, Chana Rokhl and Mordechai Kalman, would be linked. He believed that girls didn't need to inherit property, as they received dowries. Apparently, this was a biblical rule. In general, he followed the precepts of the Torah, including designating parts of the harvest for the needy, and the laws of shmitta.[7] Each worker kept his position for seven years, after which he received a plot of land and a small house, and was no longer employed by Grandfather. As we see, Grandfather's wishes were not followed; the estate was divided in 1923 between his children and grandchildren.

Skryhiczyn After the Division

Shmuel Rothenburg's children and grandchildren all created farms. They became farmers and prospered. Meanwhile, the Polish government had made rules that persecuted Jews by means of various taxes.[8] Some of the heirs went to the Land of Israel, and others to Argentina and Brazil. Grandfather Chayim decided to parcel out his share of the property, and the peasants began purchasing the parcels. Our father tried to revive the farm, but without much enthusiasm, and despaired of the project. In the meantime, Grandfather Chayim fell ill and went to Warsaw, where he died at age 67. I witnessed his death.

Let me mention Uncle Mordechai, my mother's brother. When he heard of Grandfather's illness, he came and cared for him like a professional nurse, with great love and devotion. He also prayed with him and entertained him with stories. I will never forget this uncle's kindness and affection. He was with Grandfather 24 hours a day, fed and washed him, and stayed with him to the last moment.

Grandfather Chayim died in 1927 and was buried in Warsaw next to his father Mordechai Kalman Rothenburg. As we were on our way to the cemetery, a telegram arrived informing us of the death of Aunt Leya Morgenstern, who was Grandfather Chayim's age. They grew up together and lived side by side all their lives. She was the grandfathers' niece, who had lost her mother on the day she was born, and was raised by Grandmother Itta Reyzl. When very young, she married Leybl Morgensztern, the grandson of the Rabbi of Kotsk, whose original name was Yustman (Yaushzon).

Descendants of Shmuel Zvi Rothenburg:

Sons:

The Jews of Europe were decimated, and along with them – the Skryhiczyn estate. All the survivors are in Israel, grandchildren of Shmuel and Rivka Rothenburg.

Chayim and Blumtshe's daughters lived and died in Israel: Chaya Sirkis (Jerusalem), Leya Privas, Adelia Shapira (Jerusalem), Hulya Lever-Binyamini, our mother Chana Rachel Rothenburg, our sisters Itta Reyzl Rothenburg, Gitta Rothenburg, Masha Rothenburg and family.

Our brother Yehuda-Aryeh (Leybl) Rothenburg and family were murdered by the Nazis, may their name be blotted out.

Never forget the German Amalek! Never forget the German Holocaust in all the generations to come!

Skryhiczyn [Epilogue]

The Hitlerist epidemic broke out in 1939, and the Skryhiczyn estate was bereaved, along with all the Jewish people. The descendants of Shmuel and Chayim Rothenburg were exterminated; the only family members that remained are the fervent Zionists who founded kibbutzim. Shmuel's grandchildren are in Kinneret, Yagur, Givat Chayim (Givat Haim), Kefar Vitkin, and Givatayim. Remnants of Chayim Rothenburg's family died here, in Israel: Leya Privas, Feyge Gotlib, Chaya Sirkis; and one daughter still living, Hinde Lever-Binyamini.

The following family members were killed, exterminated in the Holocaust: Mordechai Kalman and his wife Sheyndl, as well as his sons Yosef and Moshe, his daughter Chave and her family. Chayim and Masha Halperin and their daughter, Sara Goldberg, Menashe Shidlovsky's daughters Itta, Dvora, Chanaleh (Shmuel's daughter and Chayim's daughter-in-law) and her children Itta-Reyzl, Yehuda Aryeh, Gitl, Mashka and her husband Mordechai Rothenburg, Mordechai Hurwitz and his family, Yosef Hurwitz and his family.

Translator's Footnotes

Translated by Yael Chaver

From the Polish Press

|

|

When I watched the film “Fiddler on the Roof,” I wondered why we in Poland could not write a similar work, or at least a film based on Meir Ezofowicz, a work that is unique in world literature.[1] In the 19th century, no one wrote about Jews in this way. That is why I mention this novel, as well as a small book by Irena Kowalska and Ida Merżan, The Rothenburgs on the Bug River. The two writers of the latter book are cousins, descendants of the Rothenburg family. The history of this family provides material for an epic, or at least a film that would be a world success, like Singer's The Farm.[2]

According to history, the Rothenburgs originated in the city of Rothenburg, Bavaria. They apparently fled, or were banished, from there in the 14th century,[1] following a pogrom that killed all but a few dozen Jews. The family is descended from the famous Rabbi Meir Ben Baruch, who was renowned during the 14th century.[3] Their last name is derived from the town of Rottenburg.[4] The family's history is well-documented and begins with the purchase of the estate in Skryhiczyn, overlooking the Bug River. Now the site is part of Dubienka, in the province of Chelm. Skryhiczyn village was the property of the Zbyszewski family. A man of German extraction named Bergman purchased the village and began to develop it. He built a dam on the local stream (not the Bug River) and a flour mill, and stocked the forest pools with various kinds of fish. He left the village after his daughter died in a lightning strike. Itta and Mordechai Rothenburg then purchased the farm.

The Rothenburgs began to farm the land and raise domestic animals, and became farmers just like their Polish and Ukrainian neighbors. The two daughters who left the village, Irena Kowalska and Ida Merżan, and wrote the book, led interesting lives. Ida Merżan worked with the famous Janusz Korczak.[5] Kowalska (Privas) joined the Communist Party while it was illegal in Poland, spent several years in prison, and married a Polish Communist. She moved to Lwów (now Lviv), and then on to the interior of the USSR. She returned in the spring of 1945, after

[Page 135]

the war. The memories she presents in the book relate mainly to the old village of Skryhiczyn. It seems to be a place where the three ethnic groups – Jews, Poles, and Ukrainians – lived in harmony. The old photographs in the book are further evidence of that situation.

Kowalska recounts the black day of September 10, 1942, in Skryhiczyn. Several Gestapo men came to the village that day and murdered four Jews, among them her brother. They rounded up 42 other Jews and took them to Majdanek; only three of them survived and returned alive.

Only 6,000 copies of the book were printed, and thus the chances of it being widely read in Poland and elsewhere are very low.

Irena Kowalska and Ida Merżan, The Rothenburgs Overlooking the Bug River. Popular Publishers 1989, 6,650 copies, 293 pages.

|

[Page 136]

|

February 24, 1992

Dear Mr. Shachar, We thank you for sending us an account of the history of the Skryhiczyn estate, through Ms. Rachel Groysboym. The account has been added to the Archive, and is listed as No. 9495.

Sincerely, |

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dubienka, Poland

Dubienka, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Aug 2025 by JH