|

Chronicles of Dubienka

Commemorating the Martyrs

|

|

|

[Page 82]

|

|

[Page 83]

by Hirsh, the Kohen's Son

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

I remember my town, Dubienka, and its bath-house street Walking there gave us muddy feet.

Our small synagogue, covered in moss,

On that plain earth floor,

I long for my youthful haunts,

Beautiful, with trees and meadows,

Summer nights, with green frogs calling,

Dark-blue skies, glinting moon and starlight,

The mild breeze and good air refreshed us

I remember crazy Hershl and limping Daniel.

I'd love to see my beloved home, |

[Page 84]

by Gershon Shachar (Shlechter)

Translated by Yael Chaver

At long last and after much hard work, our memorial book for the Jewish communities of Dubienka, Skryhiczin, and Dorohusk is finally appearing. It will forever preserve the memory of our dear ones who were so tragically decimated by the Nazi murderers (may their names be blotted out). Gathering all the material was difficult. Our main problem was assuring the necessary funding. The Jews of Dubienka were never well-to-do, and are not wealthy here, either. It has been hard to collect the money required for the book's publication. We were able to set up a memorial monument in the center of the Holon cemetery, near the monument to our dear ones who were incinerated at Sobibor. That monument cost us 20,000 shekels, completely depleting our bank account. Yehuda Kuper (may his memory be for a blessing) put much effort into erecting the memorial on that desirable site.

Yehuda Kuper, who was extremely active in our association, also worked hard to publish this book. Whenever we met, he would express his regret at the fact that all the Polish Jewish communities had already published memorial books, but we hadn't. However, he wasn't discouraged, but worked with all his might to attain the sacred goal of publishing this book within our lifetime. Sadly, Yehuda himself did not live to see the achievement. He died on September 21, 1985. Words cannot suffice to thank him for his activity and devotion to the association. He dreamed of publishing this book, which will serve as the sole memorial to the entire Jewish community of our town. May his memory be for a blessing!

The book had a difficult ‘birth’. It took a long time to collect all the materials. Naturally, everything I received had to be rewritten and reworked. It was written by natives of Dubienka, who had endured and survived that gruesome hell, and wanted to set down everything for their children and grandchildren to read and know what had happened. Obviously, they weren't professional writers, and much work was required to correct, edit, and translate the texts, which were written in Yiddish and in Polish. It was also difficult to work with the American survivors' association. I explained that some of the material had to appear in English, as the survivors' descendants could not read Yiddish, and sent them the most important Yiddish articles for translation into English, a lengthy process that required intense correspondence. I finally received the materials in English.

We did all we could to ensure that the book would appear in an impressive format. The best memorial to our nearest and dearest would be this handsome book. Let our children and grandchildren learn about their roots.

This Yizkor Book is the sole remembrance of the Jews of Dubienka, Skryhicin, and Dorohusk.

[Page 85]

Translated by Yael Chaver

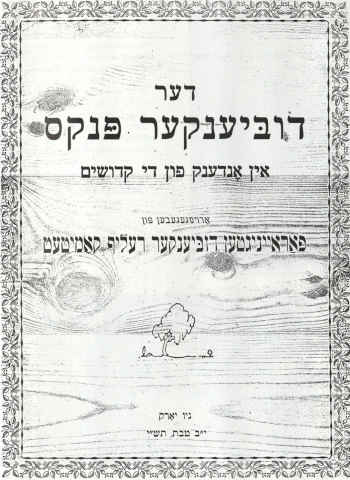

At the initiative of survivors, the Dubienka American Relief Committee published several booklets of The Dubienka Pinkes (edited by Asher Roytstein). They contained articles about our hometown and reminiscences of Jewish life there.

The town is unimaginable without its Jews. It is very painful to hear about their experiences and abuse at the hands of the Nazis during the four years that preceded their being deported to Sobibor.

I chose several Yiddish pieces for publication in our book.

Translator's Footnote

by Miriam Shiff

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

We have built a monument Of pen and ink To you, Dubienka martyrs So dear to us.

We lived together

We all studied in

We all walked

We were all transported

My town Dubienka, where are you?

Where are your synagogues and prayers? |

|

|

Translator's Footnote

[Page 86]

by Yonah Tsukerman, Judenrat member

Translated by Yael Chaver

Dubienka was a small town, separated from the world by the Bug River, with a population of 1,000 that was evenly divided between Jews and Gentiles. Many were artisans such as shoemakers, tailors, carpenters, and construction workers who built wooden houses. There was also a watchmaker, cart drivers, and others. The rest were merchants, shopkeepers, and peddlers. Very few were wealthy; anyone who had enough for bread and clothing was considered well-off thanks to his livelihood.

On the other hand, there was no shortage of synagogues. First and foremost, we had a beautiful Large Synagogue, where ordinary folks prayed, such as shoemakers, tailors, etc. The large Study House stood across from the synagogue, where butchers and other artisans, as well as poor people prayed, along with Rabbi Aharon Mordechai Suchatchevski (may his memory be for a blessing.)

The bathhouse and the mikveh where Jews came every Friday to bask in the steam and prepare for Shabbat were also opposite the synagogue. Women came to the mikveh on Mondays and Thursdays to fulfil the requirements of ritual purification. There was a prayer-house used by the members of the Kuzmir Hasidic group – the Włodawa prayer-house. In addition, there was a Turisk prayer house and a Zesrizh Study House.[1] Prior to World War I, there was a town cantor who led services in the Large Synagogue. Known as Pinyeh the Cantor, he made a living by selling wine for the Shabbat blessings. He was also permitted to come to people's homes and shops on Thursdays and Fridays to collect coins from those who were able to pay.

The town shammes was Avraham Shammes, who worked in the Large Synagogue. He would go into the markets every Friday afternoon and announce loudly: “Go home, go home for Shabbat!”

Before World War I, the Kuzmir prayer-house also had a rabbi, who was known as the Rabbi of Parczew. Although he had no children, he was very poor; he had to leave Dubienka and take up a position in Świerże, not far from our town. Świerże also had Turisk and Włodawa prayer-houses, each with its own congregation and Hasidic leader, who came to visit his devotees once a year. These visits were major occasions. The Turisk rebbe would come to his followers' prayer-house, where a meal would be set out. During the meal, the rebbe handed out morsels to the group. Receiving such morsels was considered a great honor. After the meal, the rebbe would hold a scholarly talk, to the delight of the Hasids. In the evening, the rebbe would see petitioners, most of whom were women. The prayer-house manager sat at the entrance and listened to the women's problems and difficulties. He would write each woman's problem on a note and give her the note to hand to the rebbe, who would say a special prayer for her, ensuring that everything would be resolved.

There was also a group of pious women who took an interest in families of the sick and would help them; they also took care of poor people who had no means of livelihood. These women would visit people's homes every Friday and collect challahs and other products to distribute to the needy.

Such were our lives until World War I broke out in 1914, when I was 10 years old. Our town was the scene of a fierce battle between the Russian

[Page 87]

and German armies. The Russians were defeated and had to leave town, which became occupied by the Germans. At that time, life under German occupation was not bad. The Jews found more common ground with the Germans than the local Gentiles did. However, the shelling and bombing had left most of the town in rubble. A cholera epidemic also began, felling people like flies. Slowly, thanks to government aid, building materials became available and the ruins were gradually rebuilt.

At that time, the Zionist movement began to develop. Many homes had collection boxes for the Jewish National Fund, and a local branch of the Zionist movement began to operate. It was crucial in founding a modern Jewish school, whose principal was Shlomo Lev (son of Yerachmiel the Shochet [ritual slaughterer]). He was extremely intelligent, a Bible expert, spoke fluent Hebrew, and was versed in other topics of Jewish learning. Other teachers were Yehoshua Rapoport, Moshe Lichtenstein and Avraham Lazar. I was a student at that school and learned a great deal there.

We established a drama club, which was led by Yisra'el Helfand, his wife Esther (Estashi), and his brother-in-law Moshe Tsukerman along with his wife Leah. Intellectual matters were integral to the town's culture.

During Simchat Torah of 1930, as everyone in the Włodawa prayer-house was dancing with the Torah and singing, several young Zionists (including me) sang “Ha-Tikva.” There was an immediate uproar, and the congregation began to shout at us, “Out, rascals, rogues!” Some of us were married by that time and felt gravely insulted; we immediately left the prayer-house. We called a meeting of everyone who had been in that prayer-house and resolved to leave that venue and start a club of our own.

We found a vacant building that had been a free hostel for old or sick people. It was very neglected, but we restored it, and found artisans who repaired the walls and doors and repainted it. It was now a lovely venue for prayer, and attracted many, mostly young people. However, before too long it burned down.

We then called a meeting, decided to elect a board that would establish a school, and immediately began collecting funds. The Dubienka Society in America provided $500, and the Warsaw Jewish community sent us $200. We raised the rest ourselves.

We resolved to create a school that would follow the formal government directives, thus allowing Jewish children to study in a Jewish school rather than a Gentile school. We wanted our children to have a modern Jewish education and learn Polish, without having to be among fanatical antisemitic children, who constantly attacked and insulted our young people. I was selected as board chairman, and the one responsible for the entire project. The job was enormous, and I was aided by Moshe Helfman and Pinches Schwartzberg.

We hired Jacobowicz, a graduate of an official Polish teaching program, to teach secular subjects. Hebrew was taught by such teachers as Blumkeh Kirshenfeld and others. The school was to be named “Yavneh,” so as not to irritate people who considered “Tarbut” schools not traditional enough.[2] Our school

[Page 88]

was extremely successful. Parents knew they were entrusting their children to a safe environment. The children, about 200 boys and girls, received a good education. All classes were conducted in Hebrew. It was a pleasure to hear the children speaking Hebrew exclusively as they walked along.

The school's mission was enormous, and we sought more funding. The American Dubienka Association was very helpful. Many attended our services on Shabbat and holidays. We had our own cantors (I was one) as well as a choir. Every Shabbat, services were followed by a talk on current affairs. It was a true pleasure for our children and for us. Prayers at our “Yavneh” school were attended mainly by young Zionists.

This was the situation until Hitlerite winds began blowing from Germany into Poland. Antisemitism increased by the day, and the air became suffocating. Life became impossible. Posters with Nazi slogans appeared on all the walls in the center of town, with an immediate effect on Jewish businesses; windows were smashed. The ground trembled beneath our feet. The doors of all the world's countries were locked to Jews. Fear filled the air; we dreaded every moment.

Translator's Footnotes

by Yonah Tsukerman

Translated by Yael Chaver

The day came when Hitler attacked Poland.[1] The entire country was immediately thrown into turmoil. The large cities were bombed. Before too long, Germany took over the entire country. However, under the Hitler-Stalin pact, our town was under Soviet authority. We breathed a bit more easily, believing that Russian rule would be more tolerable than German rule. However, this feeling did not last long. About two weeks later, the Russians informed us that they were leaving Dubienka and would retreat beyond the Bug River, now the new Russian border. They described the disaster that would overtake us once the Germans entered the town, and virtually begged us to flee the town and go with them. They promised us motor transportation and told us to pack all our belongings and come along. Many did go with them, especially poorer people, who had little to lose. Others, who owned property, did not want to leave all their property behind, and thus had no choice but to stay.

It was past Sukkot. The weather was cold, and snow was falling. No one could have imagined the scope of the impending catastrophe. The town was under no authority for a few days. Later, fifteen Nazis arrived on motorcycles, and carried on like wild beasts. They searched houses and removed several dozen Jews, among them were my father-in-law, I, and Rabbi Kovartovski. The Nazis placed their motorcycles in a circle and ordered us to give the vehicles a thorough cleaning. Naturally, we did the job. It was Sunday, and the Poles stood around, insulting us with filthy anti-Semitic phrases and dancing for joy.

After we had finished our task, the Germans came and cut off the beards of all those who had been working, piled the beards up in a heap that they doused with gasoline, and set on fire. We were ordered to dance the hora around the bonfire, while the Poles

[Page 89]

applauded the beautiful show. We now realized that the Russians had been right, and that we had made a terrible mistake. But it was too late now. The Bug marked the border.

Before too long, we experienced the cruelty of the Germans daily. Men and women were snatched up for hard, filthy labor, with no pay except for harsh blows and insults while we worked.

One day, the mayor, a Ukrainian, sent for a few of us and ordered us to provide a list of twelve men who would be responsible for carrying out all the orders of the Germans; the group would be known as the Judenrat. No one wanted to be a member. A second order later came, instructing anyone who had worked for the community in the city council to join the Judenrat. As I had been a member of the city council before the war, I had to be one of the twelve. They gave us three days to supply twelve men. The Judenrat was responsible for implementing all the Germans' orders. Besides myself, the members were Moshe Helfman (Chairman), Velvele Vinik (Deputy), Yonah Piness, Ayzik Sobel, Sheftl Bernshtein, Itshe Dantsiger, Aharon Mastboym, Beynish Kremfil, Yitzchak Segal, Chayim Lemberger, and Avraham Mandel. A few young men were designated to serve as policemen and fill other roles.

It was not too bad in the town at first. The Judenrat, represented by Beynish Kremfil and Voveh Vinik, supplied laborers for various jobs, such as cleaning the horses and wagons, chopping wood, and doing similar grubby tasks. Naturally, the work was unpaid, except for the blows rained down on the workers.

People came home exhausted after the day's work. But we found out that conditions were worse in other towns, and the conditions in Dubienka were considered comfortable. No Gestapo men were stationed in Dubienka; they would occasionally come in from Hrubieszow, Chelm, and Dorohusk, make our lives miserable for a few hours, and leave a few corpses behind. Jews from Warsaw, Chelm, and Lódz came to stay with us in order to escape the horrible situation in their hometowns. They lived with us, under difficult conditions.

Matters worsened after war broke out between Germany and Russia. All hell broke loose. All Jews were ordered to stitch a Star of David onto their clothing, with the German word Jude. A later order required all Jews to cut off their beards. The tragedy that followed this latest order was unfathomable. Many found it impossible to obey, and circumvented it by tying a bandana around their faces, pretending that they were suffering from toothache.

The Judenrat was allotted enough flour to provide 100 grams per day, or three kilograms a month.[2] They sent the flour to the bakery, and later gave people bread (wood for home ovens was not available). The ration also included 100 grams of sugar per month, and a few potatoes. Naturally, many people suffered from hunger, as they couldn't afford to make clandestine purchases from the Gentiles.

We were under the jurisdiction of the Hrubieszow employment office. They would order us to send them workers to cut down trees in the Khazharnie forest.[3] Workers would go for an entire week. The Judenrat

[Page 90]

requested the wealthier families to share their money in order to help those in need.

The day came when the commander ordered the Judenrat to send fifty people to work in Julbewic, a village near Hrubieszow. Naturally, orders from the Germans had to be obeyed. In order to calm the community down as well as to serve as an example, we in the Judenrat decided to send our own sons along with the other young men. We sent them to Julbewic, and made the acquaintance of the local guards, whom we paid weekly so that they would spare our children from hard labor. We sent three food wagons every Friday, carrying enough for all the workers; any boy who became sick was brought home, and was immediately replaced with another.

One fine morning, five hundred Jews arrived from Hrubieszow; they were originally from Krakow. Several thousands of Jews from that city had been sent to Hrubieszow, and then on to various smaller towns; some remained in Hrubieszow. We provided them with lodgings and ensured their survival. Some came with money; we had to provide money for the others.

This was the situation between 1939 and early 1942, when we began to suffer terrible harassment. Gestapo men from Chelm arrived daily and demanded that we in the Judenrat supply them with brandy, cigarettes, electrical devices, silverware, and the like. We would go to various Poles who had bought articles from Jews and ask to buy them back. We also purchased food from them. Everything the Gestapo demanded had to be provided. They killed several dozens of Jews before they left, and ordered the Judenrat to bury them immediately.

The village of Białopole, about ten kilometers from Dubienka, contained a factory that manufactured bricks for road-paving. The brick works, as is well known, belonged to the Goldbart family. The Nazis demanded that we send workers for the brick works, where they would receive food and shelter. Strong young men volunteered for the job, once they had heard that they would be safe and not be sent anywhere else. Twenty young men volunteered. They worked there for several months and were pleased. First of all, they had food.

One day, Gestapo men came into the brick works and removed fifty young men, hailing from different towns, and took them to a vacant house formerly owned by Jews. The door and windows were then locked, and Germans holding machine guns were stationed around the building. The house was set on fire, and all the men inside were incinerated. Only ash was left; there were no bodies to bury.

The Gestapo did this in all the Polish estates where Jews were working in return for food, and killed them all, as well as in villages where Jews worked. The boys of Julewic returned home and looked for work among the Poles in the region, as they tried to avoid the murderers.

In early March 1942, the Judenrat was informed that a thousand Jews would be arriving from Hrubieszow in three days' time, and needed to be supplied with lodging. Naturally, we were struck dumb. Where would we find lodgings for them? The Germans had appropriated many houses, and we were already hosting five hundred Jews from Krakow. How could we take care of an additional thousand? But there was no choice. We had to accommodate them. We prepared all the study houses and small synagogues, as well as empty warehouses

[Page 91]

and readied a kitchen in Rokhl Eylbirt's home. Everything was ready, and we awaited our guests.

It was just before Purim, and the weather was damp and cold to the point of frost. On Purim itself, a thousand men, women, and children arrived, exhausted and beaten. They were a horrendous sight. They were from the town of Wielicka and its environs, had been driven out of their town and ordered to march in the snow to Hrubieszow. Many had fallen exhausted along the way, and were shot.

The people who arrived in Hrubieszow were more dead than alive. They were distributed in other towns of the same district. We shuddered at the first sight, and our tears began to flow. We realized they would not survive if they were housed in the warehouses and synagogues, where there was no heating whatsoever. We therefore decided that each family would have to house several families, no exceptions allowed. I housed three more families. We set up a kitchen for all the newcomers, where soup and bits of bread were distributed twice a day.

The conditions were indescribable. Each home housed several more families; everyone slept on the floor. It was extremely dirty, and the crowded conditions caused illness to break out. There was no physician or medication, and people could only wail and moan.

People lived under these grim circumstances until the day that the Judenrat was ordered to supply 500 wagons early the following morning, to transport everyone to Hrubieszow. I immediately convened a Judenrat meeting, to discuss our options. Naturally, the terrible news had spread throughout the town by word of mouth.

It was a Saturday, when a messenger from Hrubieszow secretly brought a letter from Moshe Helfman, chairman of that town's Judenrat. We immediately opened the letter, and read that Jews were strictly forbidden to leave town for the next three days. Furthermore, all the Jews who were working for landowners or other Gentiles in villages had to return to Dubienka immediately. This included Jews working in Skryhiczyn, Rogatka, Seliscz, and other villages.[4]

The Jews returned to town and waited for the sentence to be imposed. People began packing, and made bundles of objects they wouldn't be able to take with them and planned to deposit with Gentile acquaintances for safekeeping. On Monday afternoon, two Gestapo men arrived on horseback and went to Helfman's house, which was near mine. The mounted Germans began yelling instructions into the street: “All the Jews must be at the marketplace by 6 a.m. tomorrow. People can bring 20 kilos of baggage with them, as well as money and jewelry – but any foreign currency should be handed over to the commander. They should also bring food for three days. We'll take you to a place where you won't be harassed by people of other nations, and you'll be able to live freely according to your wishes. Those who don't obey these instructions and hide will be hunted by policemen, found, and shot on the spot.”

We asked how everyone would be notified of the 6 a.m. assembly time; after all, we couldn't go out to let them know, as Jews were under curfew

[Page 92]

after 9 p.m. They responded that tonight would be an exception; we could go out without fear of being harassed. “You can go from house to house and let everyone know.

Once again, people began to pack. Those who had flour baked enough bread for three days. At 6 a.m. the next morning, everyone was at the marketplace. The two Gestapo men who had gone to Helfman's house consulted a list and called out the names of two hundred Jews who were ordered to stay behind, apparently because they were needed for work. The others, about four thousand in all, were told to get onto the wagons and were taken to Hrubieszow, accompanied by the German murderers.

The trip to Hrubieszow was not too bad. The Germans pretended to be taking them to a place where they would be able to rest. None of the Jews in the wagons were harassed, or even insulted. On the contrary, the caravan even stopped from time to time to allow people to eat and attend to their bodily needs. The tragedy began once they arrived in Hrubieszow. A large area around the train station was encircled by barbed wire. Germans holding machine guns were stationed along the fencing.

The moment they entered the square, they were greeted by shots fired at the exhausted travelers, who were incapable of moving. Among the twenty people shot then and there was the old rabbi, Aaron-Mordechai Sukhachevsky (may his memory be for a blessing).

The bitter truth was now clear. Unfortunately, escape from the enclosure was impossible. The entire marketplace was ringed by Germans with machine guns. Everyone knew that it was the tragic end. Some Judenrat members, including myself, approached the Hrubieszow Judenrat and asked whether some townspeople who had been separated from their families could be released. We were told that nothing could be done. Moshe Helfman and I went to the works inspector, carrying a large sum of money, and begged him to do us a great favor and use his position to request the release of those men he required for labor. He told us to prepare a list of one hundred names and promised that he would immediately free them. We gave him a list; he started calling out names and began to take them out of the enclosure. The guards couldn't oppose him, because of his official role.

Once he had concluded, the SS commander came up and asked what he was doing; he responded that he needed the men to finish a job that he had been ordered to do. The SS commander told him, “Let these men stay here, because they are already on the list for this transport. We'll give you the laborers you need tomorrow, when a group from another town will arrive.” Naturally, there was nothing the works inspector could do. He came back with the sad news, but did not return the money and gifts we had given him.

We returned to Dubienka broken and ashamed. Those who awaited us did not need to ask any questions; they understood, the moment they saw us.

[Page 93]

On our way back to Dubienka through the Khazharnie forest, a group of waiting Germans tossed us off the wagons and beat us up. We all fainted, but were forced to stand in a row and await execution. A Polish forester, a client of mine whom I knew very well, begged the Germans not to shoot us. They let us go, but kept the wagon, horses, and Polish driver. We had to walk back to town. Half-dead, we trudged the twelve kilometers back. When people saw the state we were in, everyone knew what the fate of Hrubieszow's Jews would be.

The Jews assembled at the Hrubieszow marketplace near the train station were kept there without food or sleep for two days. On the third day, trucks came from Wofno, loaded everyone up, and took them to Sobibor, near Włodawa, where gassing vans were set up to murder them.[5]

That was the end of 4,000 people. The remaining 150 Jews suffered in Dubienka until after the Sukkot holiday, when they were taken to Hrubieszow and joined several thousand Jews from other towns. All were deported in crowded wagons. Among them were the Chairman of the Hrubieszow Judenrat; he committed suicide by poison on the trip.

Some of us fled, including my wife and me along with our three daughters. My oldest daughter was caught, along with a group of Jews from Chelm who had previously been in hiding. All were shot. The only survivors were those who had fled with the Russians or had hidden successfully, about fifteen in all.

|

|

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 94]

by A. Kogut

Translated by Yael Chaver

It was the eve of Shavuot, and I was hiding in the village of Janostrów. Rumor was that there would be a raid to seize people for labor. People also said that those who had money could go to the Judenrat, whose members would ask the landowner to require laborers. This indeed was the case. The landowner took Chaya-Ester Kuper; Yosef Kuts and his son; Chayim Teller's two sons (Leybl and Shiyeh); Peretz's son; and Gershon, Moti Shindel's son. They worked there for some time, until one of the Gentiles informed on them. An SS unit came, shot them all, and buried them on the site.

When the Jews of Dubienka were taken to Hrubieszow, about seventy were left in the town to finish various tasks. They requested permission to remove the bodies from the mass grave for reburial in the Dubienka cemetery and were able to do so. We buried Chaya-Ester separately.

In the summer of 1939, Hersh Hochstein and I were drafted into the Polish army, and served in Kovel. After the Polish army surrendered, I came back home to Dubienka. Germans already ruled the town. They took Jews for labor, which included washing the Germans' boots and other articles of clothing. The attitude towards the Jews was horrible; there were beatings and murders. We heard daily of people being shot. Gestapo men would drive in occasionally, shoot a few Jews, and leave.

Early on the day before Shavuot of 1942, Gestapo men came into town in order to perpetrate a massacre. They did not succeed but did shoot a number of Jews. These were Anshel Baniak, Moyshe Klinker (who was chopping wood for the priest), Yisro'el Shtsigler, the shoemaker, Chayim Bufer the tailor, Leybish Fulkartz, Yitzchok Uriness, Yisro'el Beyder and his wife and Zisl, the female bath-house attendant, Chayim-Barukh Libman, and Sholem Forvis (Dantsiger). People had long ago stopped going to the synagogue to pray, for fear of being shot by the Germans; synagogues were the Germans' favorite. The Germans and others took everything out of the synagogue, including the Torah scrolls and the beautiful hanging lamps. The building was taken apart; the Germans took the bricks to build a road in Ciechanów, and used the cemetery gravestones as walkways near their houses.

The town was suffering from severe hunger, and people roamed the villages in search of food. Some were killed on the roads, not only by Germans, but by other Gentiles who took this chance to kill Jews. I hid in the attic of a Gentile's house, who kept reporting on the identities of those being taken for shooting at the cemetery. One day, Nochem Rot, the daughter of Reyzl, Leyb's wife, as well as a woman with her two children were shot. The last victims might have been from a nearby village.

As I lay on the attic floor, they told me that Itche-Meir's wife and son were enroute to the cemetery. She couldn't walk, and was in a small cart. I soon heard shots; the cemetery was only a few hundred meters away from the attic where I was hiding.

One day, the Gestapo came to Itche Meir's house. They searched the attic and shot everyone they found.

[Page 95]

Hershl Vogenfeld was also shot at his home the same day. One Saturday, Yitzchok Kotler and his two children, along with Toybe (Serele's daughter), and others, were brought from the Strzeleckie-Strzelce forest and shot. It was rumored that an airplane had flown over the forest to search for concealed Jews; once it had found a group, bombs were released and all the Jews were killed, including Shiyeh Sobel.

The day before Shavuot, all Jews were ordered to report to the marketplace. Those who didn't report would be shot on the spot. Four hundred wagons were waiting at the marketplace, near Rokhl Elbirt's house. The Jews were loaded onto the wagons and taken to Hrubieszow's train station, where many Jews from various towns were assembled. The Jews were surrounded by Gestapo men holding machine-guns. I was one of seventy Jews who were freed for labor assignments. Some of us sneaked onto the wagons and reached Hrubieszow with the transport. I was able to meet my wife there; she reported that everyone was going to be taken to Sobibor and exterminated.

I had a special work permit, which I presented to the guards at the entrance; they allowed me to leave. I went back home to Dubienka, immediately reported to the local Judenrat, and told them that I had heard about the transport to Sobibor planned for the next day. When the members heard my report, they hurried to Hrubieszow, hoping that they could save Jews from Dubienka who were needed for work. Sadly, they were unable to do anything. Yonah Tsukerman and three other Judenrat members returned dejected. Before they had said a word, we knew that they hadn't been able to save any Dubienka Jews.

We later heard that they had all been packed into trucks. Yankl Hitlmacher was one of the seventy who were released with me. He was standing near the wagons in Hrubieszow and was shoved in with everyone else (including his wife and children) and sent to Sobibor.

Yehoshua Kuper, Bentziyon Kuper with his wife and children, and Noyekh Gayer's son-in-law were shot in the cellar of their home, where they were hiding. Mendl Sobel and his sister-in-law Roza were shot during Liberation, as the Russians entered the town.

It was harvest time; I was hiding in the attic when I saw the Russians come into town. When I emerged onto the street, I saw many buildings on fire. Suddenly I heard my name being called out. It was Chava Tsukerman, with Yonah Tsukerman's daughter. She reported that Hersh Edel had been shot at the pool near the mill. When the Germans left and the Russians entered, the Jews had been hiding among the fish. Avrom heard people speaking Russian and raised his head to take a look. He was immediately noticed and shot by a Russian soldier. Though he was taken indoors, and a doctor was brought, there was nothing to be done; he was dead. Yonah Tsukerman later came with Avrom Gruber and Moshe Brener, and took him to the cemetery.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dubienka, Poland

Dubienka, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 07 Aug 2025 by JH