[Page 45]

The Holocaust

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

|

|

In commemoration of the souls

of those killed as martyrs.

May God remember the souls of the three thousand martyrs of our town,

Dubienka, who were killed and burned by the Nazi murderers

and the Polish Fascists of our town, on June 2, 1942,

as well as the souls of two hundred and fifty martyrs of our town,

Dubienka, who were tragically murdered by the Nazi murderers

and the Polish Fascists of our town, on November 6, 1941.

May their souls be bound up in the bundle of life.

May God take revenge for the blood of His believers.

|

|

[Page 46]

The Monument to 84 Towns at Sobibor

|

|

The Monument of Eighty-Four Stones, bearing the Names of

the Eighty-Four Communities destroyed in the Holocaust |

[Page 47]

The Commemorative Plaque at the Memorial Monument, Holon Cemetery

The Holon Cemetery contains a section dedicated to monuments to the Jews of various cities and towns who were murdered by the Nazis (may their names be blotted out). Some of the monuments include the names of families murdered in the Holocaust. I immediately thought that this was a worthy way of commemorating the names of our dear ones who were murdered, and that a plaque bearing the names of our murdered dear ones should be placed near the Sobibor Monument in Holon. They were murdered in that camp, and their only remnant was a large heap of ashes. We needed to create a plaque.

I started work immediately, created a plaque, and attached it to the right-hand side of the monuments. I wrote to survivors of Dubienka, Skryhyczin, and Dorohusk, explaining my plan, emphasizing its importance, and asking those who wanted their family members memorialized on the plaque to send me the full names of their dear ones. Many names arrived and are engraved on the plaque. Please send me more names at this address: Gershon Shachar, Giv'at Chayim Ichud, 38935.

|

|

| Plaque with names of those memorialized |

[Page 48]

|

|

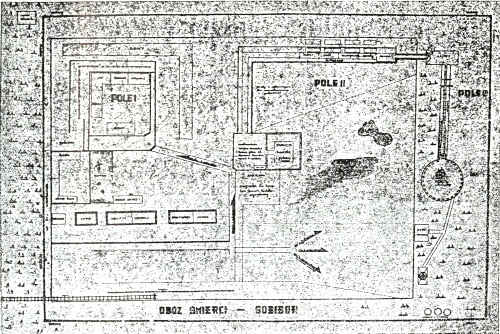

| Map reconstruction of the Sobibor Death Camp |

|

Prayer: “El Male Rachamim”

“God who is full of mercy and dwells on high, provide a true rest on the wings of the Divine Presence amongst the holy and pure ones who shine as brightly as the brilliance of the sky, for the souls of thousands of Jews of the communities of Dubienka, Skryhiczin, Dorohusk and vicinity, our parents, brothers and sisters, men, women, and children who were killed and slaughtered, choked, burned, and buried alive by the Nazi murderers, all pure and holy, including teacher, experts, scholars, righteous men. We beseech the Merciful One to shade them forever with divine wings, and to bind their soul up in the bonds of life. The Lord is their heritage, and they shall rest peacefully on their bed. And let us say, Amen.” |

[Page 49]

The Grandfather I Never Knew

by Eliezer Rapoport

Translated by Yael Chaver

(In memory of my grandfather Chayim Rapoport, and all the pure souls

of Dubienka

who were tortured and murdered by our enemies.)

I had a grandfather,

Now dead,

I never knew him

And he never knew me.

What a pity.

I never saw my grandfather,

And can't describe his face.

I only heard of him.

I knew

That he was a scholar and a righteous man.

I never knew him

And couldn't even imagine him.

I know only that he is gone,

And that he died as a martyr.

Sad, bitter thoughts!

I start to see a terrifying picture in my mind:

A crowd of Nazis holding guns starts shooting

At a lone Jew standing there, glowing,

Smiling as he stretches his neck out,

And recites the Torah verse,

“Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our god, the Lord is one,”

That verse is on his lips until the end.

The defiled earth catches his head

In the dark, the earth that

Drank the blood of our brethren

In that world of terror,

Darkness, and death.

A single drop of blood,

Still damp and shining,

Raised a monument to my holy grandfather,

Crying out,

Lamenting,

“Here, the finest man,

Chayim Rapoport, may his sacred memory be for a blessing,

Was tortured and murdered.

His death will be avenged,

His blood will never cease to lament

The souls of Dubienka's

Children, men, and elderly

Who were tortured and murdered as martyrs.”

When the world “will guard the feet of His faithful servants,

while the wicked will be silenced in the place of darkness” (I Samuel 2:9),

The pure innocent souls, the martyrs,

Will rise up and take revenge.

By Eliezer Rapoport, son of Avraham Rapoport, son of Chayim Rapoport –

grandchild of a beloved man who was born and killed in Dubienka. The town was his life.

|

[Page 50]

Our Town Dubienka

by Yonah Tsukerman

Translated by Yael Chaver

Dubienka was a small, remote town, close to the Bug River. Its population numbered one thousand, half of them Christian and half Jewish. They made a living as artisans – tailors, carpenters, and construction workers who built wooden houses. There were also a watch-maker, cart drivers, merchants, shopkeepers, and peddlers who journeyed through the surrounding villages. Very few were wealthy. Most of the inhabitants barely made ends meet; those who had enough food and clothing were considered well off. On the other hand, we were rich in prayer houses. First and foremost was our magnificent synagogue; most of the congregation was composed of shoemakers, tailors, and the like. The large study house across from the synagogue was where shopkeepers, butchers, artisans, and poor people prayed. Rabbi Aharon Mordechai Surchevsky preached there occasionally. Across the road was the bathhouse with the mikveh, which the Jews visited every Friday to cleanse themselves of the week's dirt and prepare for Shabbat. Women also used these institutions to purify themselves after menstrual periods, as dictated by Jewish family law. They came on Mondays and Thursdays. There was a small synagogue for members of the Kuzmir Hasidic group, which was active before World War I; it was known as the “Włodawa synagogue.” In addition, there were the Turisk synagogue and the Nezvizh study house.

Before World War I, the cantor was Pinyeh. He made a living by selling kiddush wine for Shabbat, and would collect money from homes and shops on Thursdays and Fridays. The synagogue sexton Avraham Shames[1] would visit all the shops on Friday afternoons and announce “Go home, go home, Shabbat is coming.” Naturally, all the shopkeepers would close their shops and hurry home to prepare for the holy day. Another rabbi was known as “the Rabbi of Parczew.” Although he was childless, he was very poor, and had to move to the town of Sverdsh, not far from Dubienka.[2]

Each of the small Hasidic synagogues had its own rabbi and congregation. The leader of each group would visit his followers every year; this was a major event. When the Rabbi of Turisk came, his followers prepared a great meal. The rabbi would share the food with his congregation; receiving food from the rabbi's table was considered a great honor.[3] The meal ended with Hasidic songs. The rabbi would also give a sermon to his adherents, who looked forward to the event with anticipation. In the evening, the visiting leader would receive people, mainly women who sought his help with their problems. The synagogue manager sat at the entrance to the room, spoke with each female petitioner and wrote out her problems on a sheet of paper, which he gave to the woman. She then handed the note to the rabbi, and he would pray for her problems to be resolved speedily and well. There were also groups of pious women who helped people who were ill as well as poor families; the women would collect food for Shabbat and holidays from wealthier households.

Our lives continued in this way until the onset of World War I (1914), when I was ten years old. The night the Germans took the town from the Russian army was terrible. The Russians couldn't hold the line, and the Germans took command. German relations with the Jews were bad, as the Jews couldn't communicate with the Germans. Much of the population fled from the bombing, shooting, and the heavy smoke. Then, cholera broke out and the epidemic overran the town; people died like flies. Eventually, the authorities helped those who had lost their houses; they were gradually able to rebuild with some government aid and construction materials.

In the meantime, the international Zionist movement developed, and our town was no exception. Many people had a Jewish National Fund collection box for donations, which were sent to the main office in Warsaw every month. We also started our own school, headed by Shlomo Lev (the son of Yerachmiel the ritual slaughterer). He was extremely knowledgeable, a Bible expert, and also knew Hebrew and other topics of Jewish learning. Other teachers were Yehoshua

[Page 51]

Rapoport, Moshe Likhtenshteyn, and Avraham Lazar. I was one of the students. We really loved it, and learned much during our years there. A drama club was also set up, led by Yisra'el Helfand, his wife Esther (Estasha), and his brother-in-law Moshe Tsukerman and wife Leah. The town was rich in cultural activity.

Interestingly, during the Simchat Torah celebration of 1930 at the Wlodawa synagogue, as people were dancing and singing with the Torah scrolls, several young Zionists (including me) began singing the Zionist anthem HaTikvah.[4] The Wlodawa Hassids were infuriated and started shouting “Out, rascals, urchins!” Some of us, in fact, were real pranksters, and we weren't happy about these calls. All of us – including those who regularly prayed there – decided to leave and celebrate Shabbat on our own. An old building that had been a hostel for the ill or elderly was empty. We cleaned it up, had it repaired by plasterers, carpenters, and painters, and turned it into a beautiful prayer hall. Everyone came to pray there, especially young people. But the building soon burned down. We didn't despair, but called a general assembly to organize the building's restoration. We approached all the institutions and sources we could think of, asking for money. The Dubienka Society in America sent us $500, the Warsaw Jewish community donated $200, and we were able to collect the rest ourselves.

We decided to establish a school that would conform to all government regulations, so that Jewish children would be able to attend it rather than the Christian school. Our children would receive a Jewish education and would also learn Polish, but wouldn't have to be in the company of the anti-Semitic Gentile urchins who harassed them and beat them up. I was elected chairman; as such, I would be involved in all school activities. There was much to do, and I was aided by Moshe Helfman and Pinchas Shvartsberg. Yakubeyevitch Havitsh, a graduate of the Polish teacher-training program, taught secular subjects. We also had Hebrew teachers, such as Blumenka Kirshenfeld.

So as not to irritate the ultra-Orthodox fanatics, who would never have agreed to the name “Tarbut School,” we decided to name our school “Yavneh.”[5] It was very successful. Parents knew that their children were in good hands and were receiving a good education. The student body numbered 200 boys and girls. It was a pleasure to hear them speaking Hebrew as they walked on the streets.

Financing the school was a major challenge. Expenses were high, and we sought financial sources. The Dubienka Society in America was very helpful. Many people came to pray in the school's synagogue on Shabbat; we had our own cantors, including me. We also had a high-quality choir. After reading the Torah portion of the week, one of the teachers would come up to the lectern and talk about current affairs. We and our children all enjoyed cultural pleasure. Most of the young people who prayed at our synagogue were Zionists.

This was the situation until Hitlerite breezes began to blow in from Germany. Anti-Semitism increased daily. The atmosphere was oppressive. The Polish slogan “Doj do swego” (“Buy from your own kind”) blared from posters throughout the town. Jewish stores were boycotted, and shop windows were shattered. All areas of Poland were closed to Jews. Travel was impossible. We all lived in perpetual fear.

Translator's Footnotes

- The Yiddish ‘shammes’ means synagogue sexton. Return

- I was unable to identify the town transliterated in Hebrew as Sverdsh. Return

- The ceremony is known as a Tische. Return

- The song, “The Hope” is now Israel's national anthem. Return

- Tarbut (“culture”) was a network of secular, Hebrew-language, Zionist-oriented schools in Poland and other parts of the Russian empire. It was active primarily during the interwar period. After the destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE), Yavneh, Israel, was the location of important Jewish sages who began to reconstitute Judaism, and laid the foundation for Rabbinic Judaism. Return

The Terrible War

by Yonah Tsukerman,

Chairman of the Judenrat

Translated by Yael Chaver

One fine morning, Hitler attacked Poland.[1] The country immediately sank into pandemonium. It was soon occupied by Germany. Our town, however, was taken by the Russians, as part of the USSR-German pact.[2] We breathed a bit more easily, as the Russians were less harsh towards Jews than the Germans. Only three weeks later, however, the Russians announced that they were retreating from Dubienka town, and their border would be on the other side of the Bug River. They described all that awaited us, and begged us to leave town and go with them. They promised us buses, said that we could bring anything we wanted, and asked us to join them.

[Page 52]

Many Jews did leave with the Russians, especially poor families that had little to lose. Families who owned shops, however, did not want to leave their properties, and decided to stay. It was not long after Sukkot,[3] and it was already very cold and snowy. The Russians left town, and for a few days there was no authority in Dubienka. Then, fifteen Nazis rode into town on motorcycles, like wild animals, immediately went to the Jewish part of town, attacked Jewish houses and hauled out several dozen Jews, including me, my brother-in-law, and Rabbi Kovertovsky. We were ordered to clean their filthy motorcycles. When we were done, the motorcycles were spotless. It was Sunday, and the Poles who had just finished their church service gathered around to enjoy the lovely sight. The Jews praying in the small synagogue were also brought out, wrapped in their tallises.[4]

Once we had finished cleaning the motorcycles, the Germans cut off all the men's beards, and placed them in the center of the square, together with the tallises and prayer books. Then they poured gasoline on the heap and set it on fire. The Jews were ordered to sing and dance around the fire. The watching Poles applauded and jumped for joy. We realized that the Russians had been right, and that we should have left with them.

But it was too late. We felt the Nazis' cruelty every day; young men and women were snatched up for work daily, and did difficult, filthy jobs. Their only pay was blows and curses.

One day, a Ukrainian man called for a few Jews and gave them three days to bring a list of twelve Jews whose job it would be to carry out German orders. The group had the German title Judenrat.[5] No one wanted to do the Germans' bidding. Our next order required every Jew who had worked in the town council to now become a member of the Judenrat. I had been a member of the town council before the war, and therefore had to join the Jewish Judenrat. Its members were Moshe Helfman (President), Velvele Vinik, Yona Piness, Ayzik Sobel, Shepsl Bernshteyn, Itshe Dantsiger, Aharon Mastboym, Beynish Krempel, Yitzchak Segel, Chayim Lemberger, and Avraham Mandel. Other young men were chosen to serve as policemen.

The first few days actually weren't too bad. Every day, the Judenrat (headed by Beynish Krempel and Voveh Vinik[6]) had to supply workers for various jobs: cleaning the horses and carts, wood chopping, and other physically demanding tasks. They were not paid; instead, they were beaten with short whips. Everyone returned home completely exhausted. Rumors from other towns were that the situation there was much worse, and life in Dubienka was considered easy, almost cushy. No Gestapo police were stationed in town. Every so often, they would drop in from Hrubieszow, Chelm, or Dorohusk and stay a few hours, during which they would rampage and cause several fatalities. Many Jews from Warsaw, Łódź, and Chelm came to Dubienka, because the situation here was relatively calm. We had no choice but to welcome them. This was not an easy task.

Matters deteriorated after the outbreak of the Russo-German war, and all hell broke loose. All Jews had to wear a patch saying “Jude,” and all the men had to cut off their beards. This was a serious tragedy: just imagine telling an observant Jew that he needed to cut off his beard! Many men couldn't bring themselves to do so, and wrapped their heads in kerchiefs, to indicate that they were suffering from a toothache.

The Judenrat received a ration of ten daily deciliters of flour per person, or three kilograms per month.[7] The flour was then turned over to the bakery. It baked loaves of bread, which were given to the people in lieu of the flour, as there was no fuel for baking. Persons also received ten deciliters of sugar every month, and a few potatoes. Naturally, many people went hungry, as they had no money to pay for secret transactions with the Gentiles.

We were part of the Hrubieszow works department. Occasionally, we would be ordered to send workers to fell trees in the Rozharnye forest.[8] The men would be sent out for a week, and had to bring food with them. The Judenrat asked those Jews who were better off to donate money so that we could help the needy.

[Page 53]

One fine morning, the Judenrat was told that it had three days to find 50 young men for work in the nearby village of Julbewic, near Hrubieszow.[9] German orders had to be obeyed, of course. We Judenrat members decided to send our own sons, to serve as an example for the residents. We sent our boys to Julbewic, and bribed the guards – whom we knew – so that they wouldn't have to do the hardest tasks. Every Friday, we sent them three carts with a week's supply of food. If one of the boys became sick, we would bring him home and send someone else instead.

One day, five hundred Jews from Krakow arrived in Dubienka by way of Hrubieszow. Apparently, several thousand Krakow Jews had arrived in Hrubieszow, and were sent to several towns in the region. We arranged housing for the new arrivals. Some of them had money, and we took care of the others. This state of affairs continued from 1939 to early 1942, when things took a severe turn for the worse.

Gestapo police came from Chelm every day and demanded goods such as vodka, cigarettes, electrical appliances, gold, silver, and other things. We approached the Gentiles who had bought objects from us, and hoped to re-purchase them in order to sell for food. But the Gestapo ordered that everything be handed over to them. Of course, before they left, they just had to murder a few dozen Jews, whom we Judenrat members were ordered to bury.

In the nearby village of Bialopole, there was a factory that produced bricks to pave the roads. This Polish ‘cygelnia’ (brick factory) belonged to the well-known Goldbarten family. The Gestapo demanded workers for the brick factory; they would live there and be fed. Some strong young men, who were used to physical labor (including Moshe Tsal's sons) volunteered when they heard that their lives would be safe there and they wouldn't be sent elsewhere. They spent several months working there, and were satisfied, mainly because they were fed.

One day, Gestapo police came into the brick factory, removed fifty young Jewish men hailing from different towns, and sent them to a vacant Jewish house, whose windows and doors were then blocked. Gestapo men with machine guns surrounded the building. Then they poured fuel on the walls, and set fire to the structure. All those inside were incinerated; there were no bodies to be buried, nothing was left but ashes.

Gestapo men roamed the large estates where Jews worked in return for food. They also found the Jews who were hiding in villages and forests, and murdered them all. The boys who worked in Julbewic returned home and sought local work, so as not to work in the vicinity of the prowling murderers.

In early March 1942, the Judenrat was ordered by the authorities in Hrubieszow to prepare housing for one thousand Jews from Dubienka. Naturally, we were appalled. Where could we house them? The Germans had expropriated many houses, and we had already housed 500 Jews from Krakow. But there was no choice. We began preparing the houses of study and the small synagogue, as well as all the abandoned shops, and set up a kitchen in Rachel Elbirt's house.

Everything was ready, and we waited for our guests. It was almost Purim[10], and the weather was cold and rainy. On Purim, one thousand exhausted men, women, and children arrived from Wielicka and the vicinity. It was a terrible sight. They had been expelled from their town and ordered to walk to Hrubieszow. Many had dropped along the way in the cold and the snow, and were shot by the Gestapo; dead bodies arrived in Hrubieszow. The survivors were sent to different towns in the area.

When we saw them, we were overcome with weeping. Clearly, they wouldn't survive a stay in the synagogues and shops, which were unheated. We therefore decided that each family had to host several of the newcomer families. I took three families into my apartment, and organized a kitchen for everyone. They were fed soup and bread twice a day. Conditions were bad. Refugee families lived in all the apartments, and everyone slept on the floor. The filthy, crowded conditions led to widespread disease. There was no doctor or medicine, and people groaned and wept. This miserable state of affairs continued until the Judenrat was

[Page 54]

notified to prepare 500 carts for early Sunday morning, when all the Jews would be transferred to Hrubieszow. I convened the council to discuss how to tackle this order. Of course, the bad news quickly spread by word of mouth, and the whole town knew what was going to happen.

It was Saturday. A messenger from Hrubieszow arrived with a letter for the council chairman, M. Helfman, as follows: no Jews were allowed to leave town, and all the Jews in the surrounding villages and farms had to come to Dubienka. Jews living in Skryhiczin, Rogatka, and Selyscz were also ordered to come into town. All the Jews in the area were in Dubienka that day, awaiting the future. Everyone was packing; people gave objects that they couldn't carry to Gentile acquaintances for safekeeping.

On Monday afternoon, Gestapo police arrived on horseback, heading for the home of the Judenrat chairman, M. Helfman, who lived near me. They called him outside, and told him, “All your Jews must report to the market square tomorrow morning. Each person is allowed to bring 20 kilograms of baggage, besides money and jewelry. No foreign currency is allowed; anyone holding foreign currency must bring it directly to the commander. They need to bring enough food for three days. We'll take you to a place where you'll be able to live freely, without being harassed by people of other origins. Anyone who fails to show up will immediately be located by gendarmes and will be killed on the spot.”

We asked how we could notify everyone, as Jews were not allowed out of doors after 6:00 p.m. They said that the prohibition would be lifted for tonight, and we could go door to door and inform people. Once again, people began to pack. Those who had flour baked a three-day supply of bread.

At 6:00 a.m. the next morning, everyone was in the market square. The two Gestapo police who had come to Helfman's house the previous day now produced lists and announced the names of two hundred people who were now told to stay in Dubienka, probably as laborers for the Germans. The remaining Jews were ordered onto the carts and taken to Hrubieszow, under Gestapo guard. The trip to Hrubieszow wasn't too bad, as the Germans didn't harass them along the way, and kept up the pretense that the Jews were being taken to a safe place where they could rest. On the contrary, they even decreed several breaks so that the deportees could eat, and attend to their bodily needs.

The tragedy began when they arrived in Hrubieszow. The train station was surrounded by a large fenced lot. Men armed with machine guns stood around the perimeter of the fence. Those who were exhausted and unable to walk when they reached the lot were immediately gunned down. About twenty Jews were murdered then and there. Among them was the old rabbi Mordechai Suchachevsky, of blessed memory. By the time everyone realized what was happening, escape had become impossible. Armed guards were stationed all around the fence. Everyone realized that this was the end. Some Judenrat members, including me, immediately went into the town and met with the local Judenrat, to see whether couples that had been split up could be reunited; the Judenrat members' response was that nothing could be done. Moshe Helfman and I took a large sum of money and went to talk to the German work inspector, asking whether he could arrange the release of people whom he needed for work. The inspector requested a list of about one hundred names, promising that he would have them released immediately.

Once he received the list, he went to the train station and began calling out names, gathering them in order to take them elsewhere. The guards couldn't oppose him because, as the inspector, he had the right to do so. Meanwhile, the head of the local SS came up and asked what he was doing. The work inspector explained that he needed workers urgently for a project under his supervision. The SS commander said that the men on the list were already listed for the expulsion transport, and that he would be able to obtain workers from tomorrow's crop. Unable to help, the work inspector returned and reported the sad news.

[Page 55]

He did not return the money and gifts we had given him. We returned to Dubienka, ashamed and heartbroken. The Jews waiting for us didn't need to ask the results; our expressions told the story.

On the way back from Hrubieszow, just past the forest, we were ambushed by several Germans who pulled us off the cart and beat us so badly that we all lost consciousness. Afterwards, we were ordered to stand in a row; we expected to be shot. At the last moment Lesznicze, a Polish customer of mine whom I knew well, begged the Germans to spare us. They released us, but confiscated the horse and cart; we were ordered to walk. We reached Dubienka half-dead, having walked twelve kilometers after the beating we had received. When the Jews in Dubienka saw us, they understood what was happening to the Jews in Hrubieszow.

The Jews who were at the Hrubieszow train station suffered there for two days, deprived of food and sleep.

|

|

| Yonah and Itkeh Tsukerman, and Chava Segal |

On the third day, a freight train with cars carrying lime arrived at the station. All the Jews were shoved into the cars that left for Sobibor, with its gas chambers and crematorium. That was the end of the 4,000 Jews of Dubienka. The 150 Jews who remained in the town languished there until after the Sukkot holiday.[11] They were eventually transported to Hrubieszow, where several thousand Jews from other towns were waiting. All were then crammed into freight cars and sent to Sobibor. Among them was Shmuel Brand, chairman of the Hrubieszow Judenrat, who took his own life on the train. Some of us were able to escape and hide with Gentile acquaintances; my wife, three daughters, and I were among them. My oldest daughter joined a group of Jews who hid in Chelm. All were eventually discovered, and shot by the Germans. Those Jews of Dubienka, about 15 in all, who escaped with the Russians, survived, as did those who hid with Gentile acquaintances. Some of them emigrated to Israel, while others went to the United States.

Translator's Footnotes

- The German army attacked Poland on September 1,1939. Return

- A mutual nonaggression pact was signed between Germany and the USSR on August 24, 1939 Return

- The Sukkot holiday is typically in mid to late September. Return

- Tallises are prayer shawls worn by religious Jews. Return

- The term can be translated as “Jewish council.” Return

- “Voveh” is a Slavic diminutive of Velveleh, itself a diminutive of Volf. Return

- A deciliter is 100 grams. Return

- I was unable to identify this forest. Return

- I was unable to identify this village. Return

- The Purim holiday is usually in early spring. Return

- Sukkot is in the fall. Return

Extract from Moshe Brener's Book

Translated from Yiddish [to Hebrew] by Gershon Shachar

Translated by Yael Chaver

As we know, Moshe Brener wrote a fascinating book on his experiences during the war. Some extracts will follow later.

When people in Dubienka heard that the Germans were quickly advancing and the Russians were retreating across the Bug River, many Jews started escaping with the Russians.

|

|

|

|

| Moshe Brener |

|

David Brener |

Moshe's family gathered to decide on the best course of action. Most decided to leave, except for one brother-in-law, Avraham Dantsiger, who owned much property, and wanted to stay. Their married daughter also wanted to stay, so that her parents stayed behind with their daughter and grandchildren. Moshe, his four brothers, and their young sister Itteh, decided to escape. They crossed the Bug River, first reaching Lyubomil and then going on to Macziow. Travel conditions were very bad, so David and his younger sister decided to return and began to move from one spot to another.

Moshe met his uncle, Pinchas Bodner, in Macziow. It was a happy meeting. Moshe and his uncle were

[Page 56]

fine workers, who were able to find construction jobs and earn some money. In the meantime, Moshe was drafted into the Soviet army.

After the Russian army retreated, Moshe decided to go back to Macziow, and eventually returned to Dubienka. After a difficult, exhausting journey he secretly arrived there. There, he went through the same hellish experiences as other Jews, who escaped to the forests and dug underground hideaways to elude the German hunters. They all fled from one hideout to the other. After the Russians retook Dubienka, Moshe became aware of the extent of the catastrophe: the town was empty of Jews. The few survivors had managed to hide with friendly Gentiles; one of those was Yonah Tsukerman and his wife.

Moshe also found out that Avraham Dantsiger, his brother-in-law, had been killed by the Germans; his friend, Volf Dantsiger, had been wounded by the Germans and was thought to be dead. However, the Germans moved Volf to Auschwitz, along with other Jews. Luckily, when the Germans retreated from Auschwitz they were unable to incinerate the last of the Jewish prisoners. Volf was able to reach the U.S. and lived in Chicago. A large group of Chicago Jews traveled to Palestine in 1945, as illegal immigrants, naturally. Once in the country, he found his brother David, who had been sent to Siberia by the Russians and stayed there for years.

Brener's book is fascinating; unfortunately, we aren't able to present it all in this Memorial Book. Below is Chapter 4 of the book, with the heading “En Route to Dubienka.”

En Route to Dubienka - Chapter 4

I walked towards Dubienka. Not too far away, there was a village where Pinchas and I had constructed a house for a Gentile without asking for money, but only for food to keep us alive. I thought that perhaps this Gentile could help me now with some money; it could be helpful in my travels.

I reached the village very early in the morning, before the residents were up and about, went into a yard with a barn, climbed onto a few bales of hay that were stored there, and lay down. It seemed to be a good plan: when the owner rose in the morning and came to feed the animals, I would talk to him with no eavesdroppers.

I soon heard footsteps and the door opened. I came down off the hay bales. Kazik, the owner's son, entered.

“Do you remember me, Kazik?”

“Yes, yes, I do – but what are you doing here?”

“I thought your father might be able to help me. I need some money. I'd be happy if he could give me a bit. If he can't, that's fine too. I need to return to Dubienka. As I can't swim, I need someone to help me across the river – and that costs money.”

“Well, my father is ill in bed. Let me go and talk to him.”

He went out, and I stayed there, waiting. He didn't go home, but headed toward the neighbor's house, about 300 yards away, and came back with the neighbor's son. Both were holding guns.

I didn't think anything like that could happen. I had done work for them, and built the house they were living in. I knew them well – but apparently they were now part of the militia. The moment the door opened, I realized that I was in serious trouble.

“Get going, start walking,” the neighbor's son said.

“Kazik, where are you taking me?”

“Shut up and start walking,” the other boy replied.

“Kazik, I haven't come to be paid for the house I built you. I just came to ask for some money – it's fine if you don't have any.”

“Move, fast,” said the boy, and hit me in the rib with the rifle stock. My only choice was to start walking. They led me through the forest. Suddenly, I saw some excavations in the ground. As we approached, I saw one covered pit and another pit that was open. Two spades lay on the ground nearby. I realized that I would soon be inside that pit.

“Do you see that pit? We already have eight Jews inside. You'll be the ninth. One more Jew, and we'll cover the pit. We'll have ten Jews in the same pit.”

[Page 57]

“Pick up the spade and start digging a new pit,” said Kazik.

I did as he said, thinking, not only do they want to kill me, but I also need to dig my own grave. No. I won't let it happen.

My heart was pounding madly and my knees trembled. I was digging with my back to them, occasionally throwing quick glances backwards. Suddenly, I saw the neighbor's kid bringing out a packet of loose tobacco. I thought, “This gives me a few minutes, until they roll their cigarettes. He might give me one and offer me a light – that would be my chance to do something.”

I broke up the earthen clods and heaped one spade full of loose soil on the side, to fling at their heads when I got the chance. I would do that and start running. If I died, so be it.

I saw them setting their guns down, as one of them bent down to light a cigarette. At that instant, I threw the spade full of soil on their heads, and followed it with the empty spade.

I didn't wait to see whether I had hit the target, but, fueled by nervous energy, began to run faster than I had ever run in my life. I swerved and zigzagged like a snake, to avoid being shot. I had run one kilometer, and they hadn't fired a single shot. Apparently, I had done a good job with the soil and flung it into their eyes. They didn't seem too familiar with their weapons, either. I continued sprinting into the forest. A few kilometers on, I stopped, and started thinking about revenge.

Rummaging in my pockets, I found the box of matches that I always kept there. This was my way to take revenge. I had built them a house free of charge, and this was their payment! Well, I would burn up my own work; if I could burn them up as well, so much the better. But I wanted them to know that I was repaying them for their deeds, and that the fire was my work, too. How would I achieve this?

I suddenly saw a boy walking to school, stopped him and took his pencil and notebook. Soon, two other boys came by. I stopped them, too, and took some bread and cheese. I was very hungry, as I hadn't eaten for a long time.

I went back and started writing a Polish message in the notebook: “This is Moshe Brener, who built you a large, beautiful house and never asked for payment. When I came to ask you for help, you wanted to repay me by killing me, and even wanted me to dig my own grave. So I've come back to burn up my work. I hope you'll burn together with the house, and everyone will find out what you're really like.”

Knowing that they went to bed early, I waited for nightfall. I knew they would sleep very soundly, as they had to get up early in the morning and work hard all day. Now I broke off some slender branches, hung my notebook pages on them, and set them around Kazik's house and the neighbor's house, for people to find. Even if one page were ruined, there would be other pages to read. I knew there were some very kind peasants in the village, whom I had helped by doing odd jobs.

Kazik's father had a large dog, which didn't bark at me when I came up; he might have remembered me. The neighbor's dog also showed up. I gave them both bits of bread and cheese. Now they were my friends. I knew Kazik's house well – after all, I had built it. There was an entrance hall, where Kazik's father kept the hay that wouldn't fit into the barn. As he didn't want the hay to become wet, he brought it into the house. I figured that if I set fire to this hay, they wouldn't be able to escape the burning house.

I went to the neighbor's house first, and set fire to the lean-to that was attached to the house, and for good measure dropped burning matches at several spots in the yard. Then I ran to Kazik's house, set two of its walls on fire, and threw the entire matchbox onto the hay. As I quickly sprinted back to the forest, I looked back once, and saw the flames.

I continued towards Dubienka and arrived at the small village of Bistrik, on the Russian bank of the Bug, with its large forest and several forest guards. I approached a man who stood there.

“Where are you going?” he asked.

“To Dubienka.”

“You're going to Dubienka – don't you know what's happening there?”

[Page 58]

He asked me in surprise.

“I know, but I need to go there.”

“Well, there's a Jew here called Jerzy Poznanski. I'll take you to him.”

I knew Jerzy Poznanski from before the Germans had arrived in Macziow. I had met him in the restaurant where he worked. My guide and I stopped somewhere on the way. He brought me water, and went to call Jerzy. Jerzy told me that almost all the Jews had been taken from Dubienka to Sobibor, including my parents and his. His brother was the only member of his family still in Dubienka. My brother-in-law Avraham Dantsiger, his brother Volf, and a few other Jews were also still there. Many Jews had fled to the forests. I parted from him, and continued to walk. Actually, I was a bit jealous when I saw how well he was set up and how safe his forest hideout was. Well, fate treats us all differently.

I went on to the village, which was very quiet; everyone was out at work. Walking along the path, I heard voices. Someone was at work there. I followed the voice and saw a man in a yard.

I walked into that yard and saw someone collecting grains of wheat grains for grinding. He was very frightened of me.

“Why are you so afraid?” I asked.

“What are you doing here?” he asked.

“I want to cross the Bug to Dubienka.”

“Oy, don't let them see you. If the Germans see you, the village will be doomed.”

“I came secretly; no one saw me. I hope the Germans don't see me, either. I just need a small favor: you live here and know the area. Is there any place where I can cross the Bug?”

“Go along the fence. Some fence posts fell into the water, and others were knocked over by carts. You can walk into the water and swim to the other side.”

“But I can't swim,” I said.

“Really? You can't swim?”

“I can swim a few yards, but not that far.”

“Ok, listen. Place a fallen fencepost under your arms, and thrash your feet. But wait until the patrol passes. They go by every two hours, and only along the Dubienka side.”

I thanked him and went on my way along the riverbank, trying not to attract attention. I found a spot where the fence had fallen, and saw a post that I could use.

I don't know what I was thinking. I figured that if I took off my clothes and tied them to one end of the fencepost, while I held onto the other end, it would be easier. I might have thought that my shoes would become filled with water and slow me down, and my clothes would balloon over my body, making me more visible. Anyway, that's what I did, and walked into the river.

The fencepost was wet and slippery. I took off my clothes and made a neat package, tying it to the post with my belt. I stepped into the water and waited in the bushes on the riverbank.

About thirty minutes later, I heard voices speaking German. They talked loudly as they slowly walked on the opposite bank, not even glancing at the other side.

I waited a few minutes, pushed the post out into the water, and started moving ahead. But my plan wasn't working properly: the post went the wrong way and I had to steer it back. This wasn't easy. I had gone a few meters when I suddenly hit a current that started whirling the post around. I kept trying to straighten it with all my might, but the post kept whirling.

“Oy, oy, oy!!”

I couldn't go on, and let go of the post, which began drifting. I dove underwater and began swimming until I got caught in bushes that provided a handhold. At that point I thought, “If God exists, He helped me just now. I've been reborn, naked again.”

Holding on to the bushes, I started heading for the small inlet that led to Dubienka. The inlet, with its clear water, had been a favorite bathing spot of ours.

[Page 59]

Separate areas for male and female bathers had even been marked.[1] I emerged from the water and aimed for the Ryczka, the small stream that bisected Dubienka, remembering that Avrum the dairyman (also known as Avraham Toybeh) lived near the stream. As I walked slowly alongside the stream, I saw two Gentile boys – the sons of Dombrowski the miller – walking along with a large dog. They were throwing the dog a stick, which it would run and fetch. There I was, standing naked, and certainly didn't want the boys to see me. I hurried into the water, among some bushes, pretending to be bathing. Luckily, they didn't notice me.

I came out of the water again, and started hurrying toward the Ryczka. Finally, I reached Avrum's garden, which bordered on the stream. Avrum knew me, and was also related to us: his daughter was married to my cousin, and his son was employed at the carpentry workshop of my brother-in-law Avraham Dantsiger. I knew Avrum was a good person. He worked for Sokhodolski.

I approached through the garden at the back of the house, and heard voices. I couldn't make out whether they were talking Yiddish or Polish. As I came closer I saw them unloading a wagon of hay. Now I realized that they were speaking Polish, and my heart skipped a beat. I couldn't tell whether Avrum was there.

I stood under the balcony, with only half of my body visible (so they wouldn't know that I was naked) and called, “Avrum Dairyman, Avrum Dairyman… Avrum Toybeh, Avrum Toybeh…”

An answer came back, in Polish, “Czego chcesz? What do you want?”

He approached the balcony. When he saw me, I said, “Hello, Avrum.”

“Who are you? I don't know you.”

“I'm Benchbik's grandson,” I said. Benchbik was my grandfather's nickname. “Don't you know my brother-in-law Avrum Dantsiger?”

“I don't know you,” he said, clearly frightened.

“I was swimming,” I said, “and Dombrowski's sons took away my clothes. I don't know where they are.”

He wasn't sure what to do about me, but I saw trousers on the balcony, the kind that were used by fishermen who caught fish in a basket at the end of a long pole. I pulled the trousers towards me.

“I'll take these, and return them to you later.”

“Walk along the Ryczka, so you won't be seen,” he managed to bring out.

I did as he said, walking on the stream bank. At Poznanski's house, I rejoined the pathway near Motl Beyker's house, and continued along the house of Yoshe Mendeleh, the cart-driver. I knew not to go near my grandfather's house (he owned an oil factory), as the Germans had set up their command center there. I walked directly to the house of my brother-in-law, Avraham Dantsiger.

I approached from the back, not knowing what I might encounter. At the back door, I turned the knob very slowly, to minimize the noise, and opened the door warily. I had no idea what I might find behind that door.

Luckily, the room was empty. I could see the front door wide open. My brother-in-law Avraham was on the balcony deep in thought, freshly washed and wearing a white shirt and black trousers.

He turned, and saw me.

“Oy, Moyshe.”

“Yes, it's Moyshe, and – oy indeed.”

Hrubieszow - Chapter 5

Avraham was surprised to see me. Who would stick his head into the lion's jaws of his own free will?

He recovered from the shock in a few seconds and ushered me in. His initial shock had become fear. I was surprised, and couldn't understand why he was so afraid. Luckily, there was no one else in the house.

He told me that all the town's Jews had been either sent to Sobibor or

[Page 60]

crammed into a ghetto. He, along with a few other Jews, was allowed to stay in Dubienka, because of his carpentry shop. The remaining Jews stayed in his house. They included Hershl Kozak, Avrum Fishlbas, and Moyshe Katuta who was a tradesman, along with his son. They traveled between villages and sold various goods.

The problematic tenant was Varshavski, a refugee from Warsaw. As he was well educated, he worked for the Germans, and the Jews were afraid that he was an informer. The Germans, who feared Soviet spies, announced that if they were not told about people crossing the river towards Dubienka, the Jews remaining in the town would be executed (about 120 in all). My presence was endangering them.

I immediately took off the wet clothes I had borrowed from Avraham Toybeh, had some food and was concealed by Avraham in his neighbor's attic. The local Poles had not yet taken over Jewish homes, and there were many vacant houses.

The next morning, after Varshavski had gone to work, I emerged from my hideout. All the Jews in the house awaited me, and overwhelmed me with questions. They also told me about their own difficult situation.

In the meantime, they had all gone to work. Avraham returned later, saying that he had been to the ghetto Judenrat (the office concerned with Jewish affairs). He had talked with Yonah Tsukerman and with a man named Heinichl, a well-educated person who was the Judenrat secretary. Avraham told them my story. They became very alarmed, and suggested that I be moved to a less dangerous place.

The main problem was passing through the German checkpoints. They suggested dressing me in hospital pajamas and transporting me in the blue cart used for moving patients to the Jewish hospital in Hrubieszow, where the situation was less dangerous and there were about 2000 Jews. I agreed, but asked to stay another day or two in order to see what was happening in Dubienka.

Later that afternoon, I crossed the street near the house where Froyim Meyshtser and his brother Sroynkl, the cart-driver, lived. I went on to the street where the hat-maker lived. All the streets and houses were empty. I then crossed the street at the large study house, near the shop, and went into Moshe Treker's house, where I decided to spend the night. The house was completely empty, with blank walls, and nothing to lie or even sit on. My only possession was my shoes, and I stood up all night.

Early in the morning, when the street was deserted, I moved into Yitzchak Unis's house, right across from Moshe Treker's home. There were a few rags there, so that I could at least sit down. At 8:00 a.m., Volf Dantsiger (the brother of my brother-in-law Avraham) came with some food.

“Look, Volf,” I said, “Why do I need to hide in this attic, with so many vacant houses?”

“Moyshe, it's very dangerous,” Volf said.

“Find me a vacant house with two doors, one facing the stream. If anyone comes through the other door, I can hide among the bushes along the stream.”

“We'll see, Moyshe, we'll see.”

He left, and came back with news.

“I found you a wonderful place. Do you know the house of Avrum Tomki, the tailor? It has two doors, and the main entrance has two sections.”

“Wonderful,” I said.

I moved into Avrum Tomki's house, where I was a bit more comfortable.

Volf had some friends who were his age, around eighteen. They came to visit me, as did Avrum and Motl Rapoport, as well as Yitschak Segal and Chave Albershteyn's daughter. They brought some treats, and we sat and talked for a few hours. Later, Avrum Poznanski came with his wife and two children. At first, I wasn't sure why they had come, but later found out later that his brother was staying on the other side of the Bug River. He had come to hear whether I had seen him, and what had happened to him. I told him that I had seen his brother in the Bisrik forest, which was a relatively quiet place with no German convoys; but that it was a matter of luck.[2]

We spent the day like this, talking about the best way to safely move me out of Dubienka. Volf suggested reserving a spot in a cart. As it was late, he went to the cart-driver, who lived

[Page 61]

near the pharmacy, to let him know that there would be another passenger for Hrubieszow. The driver was from Prussia, and was stationed among the shops near Poznanski's house.

Volf returned and said that the cart would leave at 3:00 a.m. He came to get me at 2:00.

“Let's go, Moyshe. It's time.”

“Ok, let's go.”

“Look, Moyshe. Avrom promised to send you money when you arrive in Hrubieszow. I thought that he probably didn't want to give me the money now, because the road was very dangerous; if I were caught, all his money would go down the drain. Well, I guess the money was more important than me.”

“Tell me, Volf, does the cart drive through the forests?”

“No, he drives along the Bug.”

I was planning to sit on the side next to the forest, where I'd at least be able to escape if anything happened. We'd be driving in the dark, which was better.

When we got into the cart, I was very anxious. As we drove along, I even saw the border patrol going along the Bug. The cart-driver handed me the reins for a while, as I knew how to handle horses.

Shortly before we came to Hrubieszow, the driver turned to me, looking me in the eye. “Who are you?” he asked. “I don't know you,” he added, with suspicion.

“Don't you know me?” I said, pretending to be surprised. “I'm from Dubienka.”

“What's your family?”

“Benchbik's.”

“But you weren't in Dubienka.”

“Well, then where did you pick me up?” I tried to play the smart aleck.

“If I'd known, I wouldn't have taken you.”

“But you did take me. It's done.”

We continued our drive, joking and laughing, all the way to Hrubieszow. I knew that my father's brother, my uncle Yona Brener, lived there, but I didn't have the precise address.

I started to walk around, hoping to meet him or someone who knew him. I even inquired at the Judenrat, but no one knew who he was or where he lived; the Germans had taken over entire streets that had been occupied by Jews. However, my luck was holding. I found my uncle. Of course, he wasn't happy to see me, as it would have been dangerous if it became known that I came from the other side of the Bug River.

He and his son were the only survivors of his large family.

“Don't worry, I won't stay in your house. I'll find a house, or else go and stay in the forests.”

“Look, Moyshe, you need a ‘red card’ here.”

The red card facilitated fairly free movement for him, as a merchant. There were cards for each trade.

“Is any work available in town?”

“Work… there's a lot of work here.”

“So what kind of work can I get?”

“Look, the Germans take 100-150 laborers each day, to clean the horses, remove garbage, and do other work for the city.”

“What is the work for the city?”

“Work along the roads where German soldiers were killed.”

“Doing what?”

“The Germans, you know, have maps of sites where their soldiers were killed. They kept track of those places. Now, they're digging up the bodies and placing them in boxes for transport to Hrubieszow.”

“What happens to the bodies afterwards?”

“You know, they expropriated lots near the train station, and are burying the bodies there in rows.”

“Is there any work that doesn't require a ‘red card’?

“There are all kinds of jobs in digging and in the horse barns.”

“I'll find something.”

I thanked him and went to town hall to ask for work. I was given a note permitting me to work.

We received 20 złoty a day working for the city, and 25 złoty for working with horses. As I was quite experienced in that type of work, I decided to work in the horse barns. When the German in charge saw that I had experience and knew my way around, he was pleased.

[Page 62]

At midday, he told us that he was going to have lunch. I suddenly realized that I was hungry, and remembered that I hadn't eaten for a long time. I approached him, and said that I was hungry. Everyone looked at us. He understood that they were all hungry, and took us to the dining room, where we were given hot soup and half a loaf of bread.

I wasn't ashamed to point out there was bread left over on the table where the Germans had eaten, and asked his permission to collect it. He agreed, and I gathered several kilograms of bread. That satisfied my hunger.

I decided to switch tasks and start removing the corpses of German soldiers, a job that paid 30 zloty per day. On the way to work the next day, I met Leybele Bernstein (Leybele, Shepsel's son), who used to live in Zakliczyn. We were happy to see each other.

“Oh, Moishe, how are you?”

“Not good,” I replied.

“What's the problem?”

“All of you have red cards, while I – well, even my uncle, Yona Brener, whose only other living relative is his son, wasn't happy to see me.”

“Let me tell you something. After work, go to the Judenrat office, talk to the photographer, and tell him that you need two pictures.”

“What kind of pictures?”

“Tell him they're for the red card. He'll know the size they should be. Do you have any money?”

“Yes, I worked yesterday and I'll be paid today as well.”

I was overjoyed: I was about to receive the precious red card, and would be able to continue my life under better conditions.

As soon as we finished work for the day, I hurried to receive the money and the note, and then ran as fast as I could to the Judenrat office.

When I reached the street, something looked strange. I stopped and noticed that the street was dark, and angry people were scurrying aimlessly. I heard excited conversations all around.

“Oh, hell! They won't let us live in peace.”

“Oy, it's the end!”

People were so upset that I couldn't ask what was happening. Finally, I stopped someone, almost forcibly.

“What's going on?”

At first, he wouldn't answer.

“Listen, I'm a Jew just like you. Whatever happens to you will happen to me as well, and I'd like to know what's in store.”

“The Germans ordered all the Jews to report to the square.”

The square was the former location of the market. Now, the Germans were using it in order to collect the Jews earmarked for transport to Auschwitz. The Jews of Hrubieszow and all the small towns nearby (Dubienka, Wojsławice, Grabowiec, and Nechanka) were to be collected there and taken to the train station.[3]

I quickly ran to my uncle Yona's house, and found him upset and indecisive.

“Oy, Moishe, it's our end.”

“Well, what do you want to do?” I asked.

“I don't know. I might take the horse and cart to the square. Once they see me with the horse, they might want to take me to do a job.”

“And how about the child?” I asked.

“Could you take him with you, if you're going to the forest?”

“How would I manage in the forest with a small child, with no food, no clothes, and no money?”

“Listen,” I continued. “Take the boy and come to the forest with me.”

“No, that's not my thing. I'll go with the horse, and that'll be it.”

“But I don't know how I'd manage by myself with the boy.”

“I can't force you to do this for me,” Yona said.

While Yona was making his preparations, I walked outside and heard that Gentiles had brought carts full of Jews from the surrounding villages.

[Page 63]

Those carts would return empty and they were offering to smuggle Jews out for 100 złoty. The Germans had surrounded the town, and soldiers were guarding all the roads, yet the Gentiles found a way to smuggle out Jews. The Germans did not question the cart-drivers, and allowed them to travel freely. No one imagined that Jews might own horses and carts, especially in that situation.

I did not have enough money, except for about 50 złoty that I had earned working in Hrubieszow. I began looking around for acquaintances that I could ask for 50 złoty. Luckily, I met several Jews from Dubienka.

The first was Aaron Nadsa (the son of Hershel Nadsa, the tailor), who had a permit as a cigarette vendor. He did not have enough money. Then I met Khune Estoler, the son of Sarah Estoler. “Oh, Khune,” I said, “can you lend me about 100 złoty? After the war, if we're still alive, I'll repay you.” But he couldn't help me either, because he didn't have enough money even for his own needs. I didn't give up and continued searching. I talked to Itshe Dantsiger's sons, Fishl and Moishe, who also had no money.

At midday, the Germans began transporting Jews to the train. I, along with a few other Jews, did not report to the square. We thought we had identified an ideal hideout in the hospital's attic. However, when we got there, it was already packed with people.

I began talking to one young couple. “What are you planning to do?”

“We don't know,” the man said.

“I have an idea. I know the forest. Do you want to join me there?”

“We don't know how we'll manage in the forest.”

“It's a large place, easier to hide in, and we can do many things.”

“Where would we stay?”

“We could dig an underground bunker.”

“No, thanks. We'll stay here.”

As we were talking, a family member of theirs came into the attic and said that the Germans, together with a group of strong young Jews, were doing a house-to-house sweep. Any Jew that was found was shot on the spot and buried by the Jewish group.

For the last time, I tried to persuade them, but without success.

At twilight, I left the attic and went to the river that surrounds Hrubieszow. I arrived at a shallow spot, where the water came only up to my neck. I took off my clothes and held them above my head. When I had crossed the river I started walking toward the cavalry camp. The path was pitch-black, completely dark.

I walked all night. By dawn I had arrived in a small village. A Gentile in the first courtyard I saw was hitching up his horses. I thought I might be able to creep into the cart unnoticed, but I was very hungry and thought that I might be able to get some food at that house.

I waited until the man had left and walked up to the door. I knocked, but did not wait for anyone to open it. I went inside.

There was an old woman inside who was extremely frightened to see me. I tried to calm her down.

“Madam, I'm not here to do anything bad. I'm simply very hungry, and wonder if you have anything to eat.”

The old woman gradually grew calmer, and went into the kitchen. A few minutes later she returned with a bowl of hot soup and some bread.

“Madam, you're my angel from heaven. There are very few people like you,” I said. I finished eating and parted from her.

I had a general notion of the direction that the fleeing Jews of Dubienka had taken, and where they had found forest hideouts. I reached a spot near the forest, not far from Ostrówek, where my father's friend lived. I had met this friend during my travels with Father.

[Page 64]

I arrived at the courtyard of the house, and saw the wife.

“Kasia,” I called out.

She turned and immediately identified me.

“Oh, Moishe! What are you doing here?”

“Do you happen to know whether my brother-in-law, Avrom Dantsiger, was here?”

“Oh, yes. Yes. He was here with his brother Volf and a young woman who arrived on one of the transports to Dubienka. They should be back here tonight.”

“Oh, that's good.”

“Come, Moishe, have some food and take a rest until they arrive.”

I went inside, where she gave me some food. I waited until evening, when the three of them came. When Volf saw me, he told his friends, ‘Didn't I tell you that Moishe would come? That he wouldn't be taken to Auschwitz?’”

Avrom ordered an oven full of bread loaves (the oven could bake twenty loaves at a time). At nightfall, we went to sleep in the lean-to, on the straw, and ran off to the forest early the next morning to avoid being seen. We decided that Volf and I would return that evening to pick up the bread that Avrom had ordered.

When I came to the place where the Dubienka survivors were hiding, I saw that each family had somehow gotten spades and hoes and dug itself a small bunker. I met Moti Shlechter and Avrom Katuta. An entire family–Rachmiel's son Shiyeh Cheshler and his family – was hiding in one of these bunkers. Nearby, Yitzchak Kotler and his family (including his son-in-law Hersh Peltz) had also dug a bunker. Yitzchak Segal, with his wife, son, and daughter were hiding near Chave Albershteyn and her son. I also met Moti and his brother, the two sons of Mendel's son Yuzhi the cart driver. Nearby were Avrom Rapoport and his son, well as Motl Rapoport of Łódź. Near Avrom Poznanski and Chayim Laks were the Sobols: Motl, Avrom and Rachmil, and Ayzik Sobol's son. Riveleh Gargutz and his son-in-law were also there, and many others whose names I don't remember. There were also people who were not Dubienka residents but had arrived on one of the transports. It was very noisy, more so than a market scene, because of the multitude of people, adults and children.

In the evening, Volf and I went to bring the loaves of bread, as we had decided the night before. In the meantime, Kasia's husband and his friend were making plans to rob us of the bread money and kill us both.

The four of us together were powerful: despite his youth, Volf was strong, and my brother-in-law Avrom was also muscular. I wasn't as strong, but I could hold my own, and the girl who was with us could also help.[4] The would-be robbers knew they wouldn't be able to overcome all four of us, and waited for the chance to catch the two of us on our own.

As we neared the house, we became suspicious. It was too quiet, and the house was dark, although they knew we would be coming for the bread loaves they had ordered for us and were bringing money.[5]

Knowing that the friend of Kasia's husband friend lived nearby, we started walking up the hill. They were waiting for us. We heard rustling, and stopped.

“Volf, let's run, quick. Run!” I said.

We started back at a sprint. As we did so, the two Gentiles sprang up, with two dogs, at the side of the road. We ran with all our might, realizing that our lives were at stake, saw a large trench and hurled ourselves in. The Gentiles stopped, apparently thinking that Avrom and the girl were there waiting for us. Knowing they wouldn't be able to overcome all four of us, they turned back.

We returned, alarmed, and told Avrom what had happened. We immediately decided to leave the large, noisy group, which was likely to attract not only neighboring Gentiles but German soldiers as well.

These two Gentiles, however, did not give up. They came to the group, where they recognized Yitzchak Segal, a forest engineer, with whom they had once worked here. They asked him if he needed help, saying that they could give him bread and potatoes (in return for money, naturally). Yitzchak was excited at the prospect, and asked Chave Albershteyn for her watch so that he could get food for the group.

[Page 65]

She gave him the watch, and he left with the Gentiles. When it grew dark, and Yitzchak still hadn't returned, Chave became very alarmed and started searching for him. We, who had moved away from the main group, lit a fire. Chave found us thanks to the smoke from that fire. She told us the entire story; meanwhile, the two Rapoports and Riveleh Gargutz's son-in-law were left behind.

We came back in the early morning and found the two Rapoports dead.[6] Riveleh Gargutz's son-in-law was still alive, though he was badly wounded, and died a few seconds later. Chave Albershteyn went with Shiyeh and Chave Segal to the town to search for a different hideout. As for us, we managed to find some food, and decided to go deep into the Stepankovich forest, far from the noisy group.

In the Forest - Chapter 6[7]

We had to take action, knowing that we would be in serious danger if we stayed with the large group. There were about fifty small bunkers at the site, and the noise issuing from them was as loud as that of a market. They were also near the road, and the smoke was visible over a great distance. We feared that they would draw attention and moved further into the forest, to a site where we could still see them.

There were four of us: me, my brother-in-law Avrom Dantsiger and his girlfriend, and his brother Volf Dantsiger. We were joined by the four young Sobol men, for a total of eight.

A tall, powerful young man named Lifshitz, originally from Łódź, noticed us. He approached us.

“Guys,” he said, “I see you're a group of young men. I have a lot of money, and am ready to help those who are short of money. Let's form a group of ten, and move away from this disaster.”

Lifshitz was far from a fool: he saw us preparing to move, and he had money, diamond watches, and other valuables. We would need food and tools in order to live in the forest; these now cost three times their actual value. Money was needed for bribes. Avrom Dantsiger, my brother-in-law, had money for the four of us; the Sobols had some money as well. Some time later, we were joined by Chayim Laks, and Kelnitz.[8]

Kelnitz was a forest engineer, who had been the teacher of Dombrowski's sons. He had money and property. When he wanted to escape, Dombrowski told him, “Don't take anything with you. Leave it all here. We'll keep your property for you; you'll always be able to come back to us.” Kelnitz prepared a briefcase full of money, but Dombrowski told him that we would be robbed on the road. “You're so kind and transparent. People will immediately realize that you have money, and will rob you. Come to us whenever you need anything.” Chayim Laks (also known as Chayim Teper) owned a factory in Łódź that decorated mirrors and glass plates. He had money with him.

We decided to leave very early, before the others woke up. I was the leader, as I was the most familiar with the Stepankovich forest. I also knew the forest engineer in charge of the forest. As a child, I would accompany my father on his sales routes throughout the area. Sometimes, I traveled with him for days, and thus knew the region quite well.

Later that morning we arrived at the house of the forest official. Chayim Laks had taken a diamond watch from Lifshitz, and three of us (Chayim Laks, Shlomo Sobol, and I) walked up to the house. In the courtyard, we saw the female servant.

“Hello. We're looking for the owner; we need a few cubic meters of wood and would like to speak with him,” we told her, to calm any suspicion she might have.

“Wait here. I'll call him.”

We waited outside for a few minutes. The forest engineer came out of the house, holding a large rifle.

“Oh, hello, little Froyim.” He knew me as Efroyim's son, invited us to come in, and asked that tea be brought in. We sat in the room, along with his wife, and waited until the servant left the room.

“Look, we're a group of ten young men, with no women or children. We want just one thing:

[Page 66]

Find us a place in the forest where we can hide. Let us know when the landowners go hunting, and we'll leave immediately. In return, we're giving you money as well as this.” Chayim Laks took the diamond-encrusted watch out of his pocket, saying, “Here, give that to your lady wife.” He rose from his chair and fastened the watch on his wife's wrist. Her eyes sparkled more brightly than the diamonds. “Zygmunt,” she said, I don't care what kind of business you do with them. You can sell them the whole forest if you like. This watch is never coming off my arm.”

“So, you want me to show you a spot in the forest. Let's walk outside and talk.” We went outdoors with him and walked far enough so that we wouldn't be heard from the house.

“We have one more request,” Chayim said.

“Yes, I'm listening.”

“We want you to go to Hrubieszow and get us a few things. We need a small iron stove, spades and a pickaxe; and also, matches, tobacco, flour, potatoes, beans, and other such things. This is a one-time request. We won't bother you any more.”

Chayim Laks took out 1000 zloty and handed them over. All these objects wouldn't actually cost more than 300 zloty, but we wanted him to be on our side.

“In that case, I'll go to Hrubieszow tomorrow. Come back tomorrow and I'll have everything for you. In the meantime, I'll show you a spot where you can live without being discovered by the forest watchmen. I have only one condition. I don't want women, elderly people, or children. I want to see who you are, and if you're caught I certainly don't want anyone to say I helped you.

“We're a group of ten young, strong men, and we're not afraid of a few cowardly murderers.”

We returned to the group to say our good-byes. The Sobols had their elderly uncle Shiyeh Sobol with them, and my brother-in-law Avrom Dantsiger brought along a girlfriend.

I wanted to give Avrom a piece of my mind. The Germans had only recently taken away my sister and their two children and killed them, and here he was with a girl. I was very hurt, and this would be a good chance to be rid of her.

The Sobols gave Shiyeh all the supplies they had. I saw Avrom talking with the girl and handing her some money.

That night, we avoided them and arrived at the spot where we were to meet the forest engineer. He returned before dawn, brought us everything we had asked for, and showed us the spot he had located for us.

First of all, we dug a well, and began to excavate the bunker. We marked out an area of six by two meters, and dug it 1.8 meters deep. Our sleeping area would be 1.5 meters in size, and 0.5 meters would serve as a passageway and storage area. We left a small opening, covering the rest of the bunker with branches and soil. Now that we had many supplies, the Sobols wanted to help their uncle, and Avrom wanted to give some to his girl.

Shlomo Sobol and Volf Dantsiger set off with some supplies. As they neared the large group's site, they sensed that something was off. The place that had been so noisy was now strangely quiet, arousing their suspicions. They began moving very slowly from one tree to the next. When they reached the small bunkers, they saw a terrible sight: rags and debris were scattered all around, and the bunkers were empty.

They had begun running away in fear when they heard someone calling, “Shlomo, Shlomo, Volf, Volf.” When they stopped, they saw Motl (the son of Yozhi, the cart driver) sitting there, scared and crying. “Motl, what happened? Tell us,” said Sobol. The boy said that he had left the bunker in the early morning to go to the bathroom, away from the bunkers. When he returned, he saw that about fifty young Gentiles had come, armed with iron bars, scythes, axes, and knives. Each of them was armed. They didn't let anyone leave the bunkers, but began taking the people out one by one, robbing them of whatever they possessed – even their shoes – tied them up in a row, and marched them to the village.

Later, a Gentile who had lived near Rachmil's son Shiyeh, and knew the prisoners, told the Sobols what he had seen happen to the group.

[Page 67]

It had numbered about eighty men, women, and children, who were thrust into the animal shed and surrounded by barbed wire. The following day, they were handed over to the Germans and taken to the cemetery, where ten of the young men were ordered to dig a large pit. The others were placed near the pit and then shot before they fell into the pit. Anyone who was still alive was thrown into the pit anyway. The young men were then ordered to cover the pit, leaving space for themselves. Then they, too, were shot and flung into the pit. The local Gentiles completed the job.

We stayed in the forest, and slowly set ourselves up in the best possible way. We thought that there were no more Jews in the forest, but some new ones arrived.

Moti Cheshler, who had constructed houses, Moishe Terker, and Moishe Katuta and his son knew that we were in the Stepankovich forest, but didn't know exactly where. They dug a small bunker, but were careless. Their bunker was only 150 meters away from the road, and they kept a fire on day and night. The villagers on the hill noticed the smoke, and the forest guards found them. The guards were polite and nice, asking if they had any money, and told them, “We will bring you anything you need, but it will cost you money.”

The group said that they needed nothing, and besides, they had no money. But they made a serious mistake and said too much when the guards encouraged them to talk. They said that a group of Jews was hiding in this forest. The guards asked where these Jews were, but the people in the group said, “We don't know. If we did, we would have joined them.”

The guards began to search for us in the forest, but didn't find us. We lit a fire only late at night, to conceal the smoke. Besides, the night dew dampened the smoke and prevented it from rising.

I don't know what happened, but Moishe Katuta went for a walk one night. When he was deep into the forest, he smelled the smoke from our bunker. He followed the odor and came to the bunker. Chayim Laks was on guard.

Chayim asked, “What are you doing here? How did you get here?”

“I'm glad we finally found you. We are three men and one child, and we want to join you.”

“Oy-vey, what have you done? You've been walking carelessly and leaving tracks.”

“Oy, I apologize. I didn't mean to do it.”

“We're sorry, but we have no room or food for you.”

Well, he went away. After some time, the forest guards came again, and the smaller group started to boast: “You forest guards couldn't find them, but we found them quickly!” They kept talking and revealed our location to the guards. Before long, they came to us, saying, “Do you need anything? We can help you with food and other things.” We said, “Thank you. We don't need anything; we have everything.” They understood that we were in touch with the forest engineer, and wanted to share his profits. When they talked to him, he denied everything.

But the forest guards didn't give up. They went to German headquarters, and told them that two groups of partisans were hiding in the forest. Then they told the forest engineer that the Germans would be coming to the forest the next morning. He immediately came and told us. We took the stove, tools, and whatever else we could carry, and fled deeper into the forest.

Two groups of Germans came to the forest the next morning. The first group went to Moti Cheshler's small bunker and killed them all on the spot. The second group arrived at our bunker and ordered us out, but soon realized that it was empty. They set explosive charges and blew up the bunker with the surrounding area. Soil flew everywhere. The only remnant of our bunker was a massive hole.

Another Mass Grave - Chapter 7

A Dubienka resident named Itshe-Mayer owned a restaurant in town. He was extremely pious; people would sit in his restaurant and study the Torah.

At that time, the Germans were chasing a specific group of Jews.

[Page 68]

Those Jews entered Itshe-Mayer's restaurant and climbed into the attic. The Germans followed them up to the attic and murdered them on the spot.

The Sobols heard about this from the Gentile who lived near Rachmil's son Shiyeh. The Sobols had grown up among Gentiles and now lived among them. The same Gentile related two other incidents. When Daniel Kremer was tired and lay down on a bench for a rest, falling asleep with his mouth open, a passing German officer noticed the open-mouthed Jew on the bench, walked back, took out his pistol, and shot him right in the mouth from three meters away.

Itshe-Mayer Mandel had two sons, Moishe Mandel and Mendel Mandel, and two daughters: Frida, who was unmarried, and another who married Mendel Sobol (Shiyeh Sobol's son). Sholem Sobol was also with her.[9] They managed to escape when the Germans gathered Jews to be transported to Sobibor, and were able to hide when the Germans moved the last Jews of Dubienka to Hrubieszow.

There was a large open-sided shed in Dubienka with a huge basement, where hundreds of carts would dump full loads of ice blocks. This guaranteed a year-round supply of ice. However, there had been no ice there for several years. The Jews who remained in Dubienka dug themselves a bunker in that yard. The bunker was accessed from inside the latrine that stood there. The gate was always closed, and no one ever entered the yard.