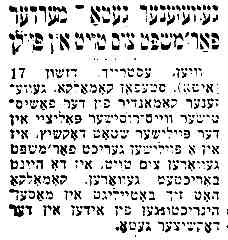

With the Partisans and In the Red-Army

By Dov Katzovitch, Petach Tikva

I was born in Gleboki and after a year moved

to Dokschitz with my parents. I was raised and educated there,

going to the "Tarbut" school. In 1939 I returned, with my family,

to Gleboki. Gleboki's population was 12000, of which more than

7000 were Jewish. The Jews' main work was small time business.

There were many craftsmen: shoemakers, tailors, blacksmiths,

tinsmiths and liberal professions.

When the Poland-Germany war broke I was

living in Dokschitz. On September 17, 1939 the place was conquered

by the Russians, and in December 1939 my family moved to

Gleboki.

From 1936 to 1939 I attended a Polish high

school in Gleboki, which turned into a Russian high school when

the place was taken in 1939 by the Soviets. There were 6 Jewish

students in my class. Altogether there were 50 to 60 Jewish

students in the school.

On June 22 1941 I received my diploma and

that same day, coming back from school, I heard a radio

transmission about the war breaking out between Germany and

Russia.

On the second day of the war we could see

convoys of military and civilian busses heading east from

Lithuania and from the western Russian border. Among the fleeing

were many Jews from Lithuania and from the western towns of White

Russia. In Gleboki people began contemplating as well. Hesitations

of this kind were to be found in my family also. In the family

were another small brother and a small girl, and the house was

very orderly - the decision was not easy.

The old Russian border was 40 to 50

kilometers from Gleboki. At the time of the Russian occupation one

was not allowed to cross the old border. Many refugees, arriving

at the town of Disna, on the old border, were sent back by the

Soviet border guards. If their papers were from Western White

Russia, they were not permitted to cross. Only those that arrived

with the Russian forces were allowed to cross (Russian clerks,

etc.). So there was also a doubt as to the worth of escaping, as

it was seen that not everyone was capable of doing so. Some,

though, did escape. The Germans began bombing Gleboki and Disna.

Gleboki was bombed on the fourth day of the war on June 26, 1941.

Civilian quarters, and not military, were bombed.

On June 28, 1941 the Germans entered

Gleboki. The next day they set up their "Feld Comandantur" (local

military headquarters) in our house, as it was big and in a

central place. The family was not yet thrown out. The Germans took

most of the house and the family stayed in a back room.

The next morning, on June 29, a German

soldier came with a gentile neighbor, age 15, asked for my bicycle

and took them. A few days later the "Feld Comandantur" was moved.

A new unit - Geheime Feld Polizei - showed up in town. They were a

secret military police. They arrested five Jews, among them a

doctor named Gheler and an ex-businessman called Ghitleson. They

vanished and nothing was heard of them since. No German authority

answered as to where they were or what happened to them.

A rumor in town said they were executed

outside the town. This caused shock in town, since these people

were not communists and were badgered by the Bolshevicks as well.

The Jews explained that they were arrested because they were

Jewish. It was hard to believe that they were executed for no

reason whatsoever.

The Germans put up signs from the "Feld

comandantur" which says:

1. Wanted people for local police. It was

noted that the candidates should be after military service and

know how to handle firearms.

2. All Jews are to wear a white band on

their left arm.

Many Jews had cows for domestic uses. German

soldiers went to the grazing area, asked who the shepherd was,

where were the cows that belonged to the Jews, and they were

confiscated for army use.

Not all Jews wore the white bands

immediately. The Germans had not yet learned to recognize the Jews

by sight. Ten days later the Germans set up a Judenrat

(a Jewish council) made of three people. Among them, the merchant, Lederman,

and Rubashkin the shopkeeper. The next day it was said that all

Jews age 14 to 50 are to gather and fix the road.

Forced Labor

The Jewish men were gathered in the central

square. A Jewish interpreter stood near a German sub-officer. They

demanded a military file. One of the Germans brought a machine

gun, placed it facing the file, loaded the gun and began playing

with it in front of the people. The people were divided into small

groups and every group went off with an armed soldier. Some went

to mend the road leading to the town, and others went 500 to 700

meters with the group. If a small defect was found in the road,

the German would order a large part of the stones to be taken out

and fixed with stones brought from afar. This was before noon.

After a lunch break of half an hour, I was sent with a large group

to mend the road leading to the town. On the road were German

convoys. They understood that the workers were Jewish and shouted:

"Juden, Du habst dem Krieg Gewollt" ("Jews, you wanted the war"!)

- well, there you have it". This was shouted even by officers.

Others laughed: "Das ist das derweilte volk" ("These are the

chosen people")

Finding a small defect in the road, the

Germans would order a quadrilateral hole dug, large rocks to be

arranged on it's bottom, medium sized rocks over them, and small

ones on top of that. In another hole they would order an opposite

order of work. Sometimes they would order a pile of rocks to be

moved from one side of the street to the other and arranged in

geometrical shapes, without any explanation. The work went on this

way for quite some time.

One day I was sent to the high school, where

two weeks before I had finished my studies, to do some cleaning

work. The place was a communications center, and there were many

cars with telephone switchboards. One of the German guards, a

communications man, ordered me to straighten a hole in the ground.

When I finished, he said the hole was not straight enough and I

had to redig it. The German shouted that all Jews were pigs and

that they should all be killed. He moved his hands as if loading

his gun and ordered me to dig again saying it was to be my grave.

Another officer needed some benches moved to an assembly room and

saw me. He sent me to do this and so I was saved.

Rumors circulated in Gleboki that in nearby

towns Jews were murdered by the Germans and the local police. Most

local police were Polish. They suffered under the Russian

occupation and accepted the Germans liberators. The orders,

documents and bulletins of the local police were all in German and

Polish.

Convoys of Russian prisoners began marching

through the town, all in chains. There were tens of thousands.

Their clothes were torn and many were wounded. The Germans

escorting them had sticks with which they would beet them

ceaselessly. Among the prisoners, according to their uniforms,

were air force soldiers, artillery men, young people -

nevertheless, they did not object, although the Germans were few.

The first rows of prisoners would have the bicycles and equipment

of the Germans, and even these were beaten for no apparent reason.

Sometimes, the prisoners would be put into Jewish synagogues to

sleep. Since their clothes were torn, they would wear a Talith and

parchments of the Torah. There could be seen on the streets

soldiers wearing pieces of the holy scriptures and Taliths on the

streets. Apart from the prisoners going to the jails, there were

groups of Russians with no German escort. These were former

Russian prisoners that had escaped from jail.

Two days before Yom Kippur, the Germans

decreed that they were creating a ghetto for the town Jews.

Notices were posted saying there should be distinction between

Jews and non-Jews so that the Jews could not influence the

non-Jews. To this end were allotted a few streets at the end of

town and gentiles living there were evacuated and installed in the

empty Jewish houses.

It was announced that Jews were not allowed

to by groceries and to sell things. At that time a Jewish police

was organized and the white band was exchanged for a yellow star

of David, the diameter of which could not measure less than ten

cm.

One star of David on the chest and another

on the back. Jews were not allowed to walk on the sidewalks

outside of the ghetto, nor walk in couples. Walking was permitted

only single file near the tip of the sidewalk. Sometimes, the

Germans leading the Jews to work would force them to sing Soviet

or Jewish songs.

The local police and the German authorities

demanded furs, diamonds, boots, fabrics, silver and gold from the

Judenrat. They promised that in return for this bribery, the Jews

would come to no harm. The Judenrat and the Jewish police knew

where to find these things and demanded them. My family, having

worked as dentists and denture makers, had gold as well. At first,

they asked for 150 gold Rubles, and later for 300 gold Rubles.

According to the Judenrat, the gold was given to the Germans and

the local police.

The Jewish police did not wear the yellow

patch. They had a white band on their arms, which showed: "Juden

Polizei".

In the beginning, the Polish police would

get friendly with the Jewish police. They would drink with them

and blackmail them. Sometimes the Jewish police would be cruel to

Jews for not being on time for work or not filling the bribe

quota. The Germans, talking to the Judenrat, convinced them that

the Jews will be given autonomy, and that this suffering is only

because of the warlike acts. The Germans would often point to the

map of Russia and said they would conquer Moscow quickly, two

weeks at most. They understood it was difficult to take Russia in

winter, and so everything had to be finished until winter. Looking

at the map, they would always be amazed to see that after Moscow

they would still have much more, and would ask if it is cold in

Siberia.

Retreating, the Russians took with them

thousands of prisoners. The people saw the huge quantities of men

in the Russian jails. Some of these convoys, led by N.K.V.D.

jailers, were bombed by the Germans on the way and would disperse.

Some prisoners joined the German police. Near Gleboki, was an

ex-monastery called Berezowich. Under the Russians it was a jail.

The Germans made it a prisoner camp. The prisoners were held

outside - in the cold and rain, with no food. At nights they would

be shot with sub-machine guns and killed by the thousands.

A month after the beginning of the war I was

sent to work in a printing press. A German brought in a text for

green propaganda leaflets, saying all the Soviet marshals are

imprisoned. At the end, in brackets, it said that whoever presents

this leaflet is a "deserter" from the Russian army and as such,

will be treated well by the German authorities.

A few days after the printing I saw a group

of prisoners led by a German and some held the green leaflet. One

of the Germans hit a prisoner although he had a green leaflet.

There were no cases of escapees from the prisoner camp, although

the prisoners were young and healthy. Some of the prisoners

appeared in town. Most were Ukrainian. One of them, a Russian

citizen, but of German nationality, was released. These were well

dressed, ate well and walked unescorted.

Organization of the Gleboki

Ghetto.

The Judenrat oversaw the accommodations of

the Jews in the ghetto. Many families in each room, of course. The

ghetto was made up of two parts, a large one and a smaller one,

where it was more crowded, of course. Before, the poor Jews lived

there and some gentiles. Now, the gentiles were moved to the

Jewish houses that were emptied. Fencing the area allotted for the

ghetto was commenced. A number of streets were blocked across by a

high wooden fence. The two ghettos were connected by a narrow

corridor. Not far from the German-Polish police station a gate was

made in the fence. This was the only entrance or exit. On the

inside stood a Jewish policeman and on the outside a

German.

The Judenrat and the Jewish police were in

one of the houses. In the cellar was a prison for Jews that had

not gone out for work for some reason or Jews that did not pay the

bribes.

In the house facing the Judenrat, the

Germans allowed a 10-bed hospital to be set up... for a population

of more than 7000. All Jews were given yellow identification

cards, since the text was the same given to the general

population. Under nationality there was a blank, under religion

there was "Mosaisch" - The Moses religion, and in brackets was

written "Jude" - Jew.

The Germans had no office inside the ghetto,

nevertheless, they constantly walked around. If a Jew met a

German, he would have to stop and take off his hat until the

German passed.

In the fall of 1941, Gypsy wagons were

brought into the Gendarmerie yard. The Gypsies were brought with

their women and children. The Germans laughed at them and called

them "wald juden" - the Jews of the woods. A rumor spread that

they were to be put in the second ghetto with the Jews. To prevent

this, the Judenrat asked for another bribe quota for the Germans.

It turned out that the Gypsies were shot with their women and

children before dawn. This event caused severe shock to the Jews

as it was not clear why the Gypsies were shot. It only went to

show how cruel the Germans were.

Every morning groups of Jews would set out

to do forced labor. The winter began, it snowed and the Jews were

forced to clean the snow from the roads as the German

transportation could not pass.

Jewish refugees from all the small towns

around Gleboki began arriving in the ghetto. They told of the

horrible slaughter going on. In most cases the Jews would be told

that they were being transferred to a bigger ghetto, and to pack

their belongings. They were told of the concentration areas. The

ghetto was surrounded by German and Polish police and from the

concentration areas they would be led to pits dug ahead of

time.

At the end of the fall, on October 1941, a

German, civil authority arrived in Gleboki. Gleboki was decreed

the center of the county - " Gebiet", and in Gleboki was the "

Gebietskomisariat" - the civil authorities.

The administration men wore the uniform of

the NAZI party, with a red band and a swastika on the arm on a

white background. The Jews thought, that with the arrival of a

civil government would stop the violent harassment. Actually, the

Gebietskomisariat's men would take to the surrounding towns to

organize the Jewish slaughter.

There was a "Religion, Nationality and Jews"

department in the Gebietskomisariat. It's chief was a German

called Havel. Often, Havel would invite the head of the Judenrat -

Lederman, or the head of the Jewish police - Yehuda Blank, and

demand a bribe. Sometimes, he would arrange matters in the work of

the Jews.

Among the Gebietskomisariat's men was a

German named Witwitzki. He was a circus performer and resided in

Gleboki as a Pole. As it turned out, he was an under cover German.

He knew, personally, many people from Gleboki, and was one of the

organizers of the slaughter in Dokschitz.

In the beginning of the winter (the end of

Dec.1941 - beginning of Jan.1942), there was a change in the

Germans' attitude toward the Poles. The official language ceased

being Polish and became Bialorussian. The police was also renamed

The people's Bialorussian police. They received black uniforms

with a gray collar and gray sleeves.

Arrests were begun among the Polish

population. Former land owners were arrested and even priests.

Between the ghetto and the Berezowich camp was a "Stalag"

(Stabiler Lager - a permanent camp) and near it a grove called

Borok. Deep pits were dug there, 3 to 4 meters deep and tens of

meters long. The stalag prisoners killed or frozen to death during

the night would be brought there. Also, in the morning, they would

kill all the suspects arrested the day before, and they would bury

them all in one pit. I was told this by the Jews working in

covering the bodies of the murdered.

The First Slaughter in Gleboki

On the second day of Passover in 1942, I

awoke in the morning and saw havoc in the ghetto streets. I lived

on the outskirts of the ghetto. The family dressed in a hurry as

heard they were arresting people in the ghetto. The arrested were

taken from their beds early in the morning and led to the Borok

grove. Two people, trying to escape were shot immediately. The

local Bialorussian police would enter a house, take out a number

of people, without any order. Germans stood in the streets, and as

a large group gathered, they would count off a hundred, and take

them to Borok, where they were shot. During the arrest, the local

police was also violent to the arrested, they beat them with the

buts of their guns. It should be noted, that policemen that had

drunk with the Jewish police the night before, were also cruel to

the Jews. Among the killed was a Jewish policeman. It seems there

was a German decision to execute a hundred men exactly. On that

day, some people did not go out to work. When the Judenrat

complained to the Gebietskomisariat, they pretended that the whole

thing was the local police's doing and promised it would never

happen again. To prove this, they released the arrested men that

had not yet been killed and before the evening, even some of the

dead men's clothes were returned to the ghetto.

The next day, life went on at the ghetto as

if nothing had happened. Only there were more widows, orphans and

bereaved parents.

In the beginning of spring, end of April,

beginning of May 1942 I saw many wounded men wearing rags around

the ghetto. These were people from the town of Sharkowshtshisna.

It seems, that during the slaughter in this town, some people,

men, women and children managed to escape to the forests. Some

were caught by local farmers and handed to the local police

station where they were immediately shot. Others, with the help of

Polish or Bialorussian farmers (the population was mixed), or

without them, managed to hide. The Germans understood that they

were unable to catch all of them and so announced that escaped

Jews returning to the Gleboki ghetto would come to no harm. Jews

began to leave the forests and to come to the ghetto. They looked

injured, flee bitten, swollen. The Jews in the ghetto understood

what would happen to someone trying to escape and hide in the

forests. The Germans wanted to put all the escapees back into the

ghetto and achieved another goal: They scared off potential

runners. These, saw the ones returning, and were

frightened.

The Work

Since the Germans wanted to organize a

Bialorussian civil government, they needed many forms. They did

not have paper, or did not want to give paper to the local

government and began taking packs of Polish and Russian forms from

the archives and sending them to the printing press. I was put in

a group whose job it was to bring the packets and sort out the

papers according to size. We would print on the back side. We

would print receipts and forms for the local Bialorussian

councils. Most of the men in the press were Jews, only one

Christian worked there.

The press was situated a kilometer away from

the ghetto and we would come there every morning. Then, the

workers were allotted a house near the press and could not return

to the ghetto as they began working in shifts. I could see my

parents in the ghetto only once a week. The press workers were

given a small salary to sustain themselves. They would buy

groceries from the neighbors.

Since there was an austerity regime in the

occupied area, they needed tens of thousands of food stamps.

These, too, were printed in the press. Most of the work was forms

for the local councils. I got the job because my grand-father had

a printing press and it's workers helped me get in.

The forced labor the Jews had to do during

the winter was mostly shoveling the snow off the roads and

cleaning for the Germans, since German convoys would constantly

pass through the town and sleep there. Also, they worked as

porters at the train station and in the slaughterhouse.

In the press where I worked, we printed also

identity cards for Jews and non-Jews. Many non-yellow forms were

passed on to Jewish acquaintances in the ghetto, so that they

would have "Aryan" papers in case they escaped. Sorting out the

papers, we found packets of Christian birth certificates and

baptism certificates which were also passed on to Jews. One Jew

succeeded, with one of these birth certificates, to escape from

the ghetto, set himself up in Vilna, and wait out the war. Today,

he is living in Israel.

When the Jews went to work they would take

with them (Unseen, of course) clothes, rings, watches and other

valuables.†While working they came into contact with gentiles

to whom they would sell these for money or food.

The Jews' contacts with the P.O.W.'s were

limited to the mutual forced labor. The Germans tried to prevent

mutual influence. The only place where Jews met with P.O.W.s was

the Borok grove, where the wagons full of "Stalag" dead would be

brought.

The majority of the population was hostile,

but there were, nevertheless, cases in which the horrors of the

Germans and the executions of non-Jews generated revulsion

especially with orthodox gentiles, and there were cases of aid.

Many Christians would say to the Jews: "Run from the ghetto,

you'll be killed in the end." Though this was but advise, and not

a willingness for real help. Only with the deterioration of the

Polish-German relationship, specially after the founding of a

Polish government in exile in London, did the Poles incline more

to help the Jews. They, themselves, were persecuted by the

Germans.

The Polish minority was small and the

population was mainly Bialorussian.

There were no political parties, trends or

youth movements. Neither did schools, "haders", yeshivas, studying

or lecturing exist. However, there was a religious culture,

religious manners. On Sabbaths, we would go to prayer before work,

if it were possible and even in the most difficult of times, one

prayed in one's house. Matzas were baked from leftover flour, in a

symbolic way.

Self Sacrifice

In the town of Dokschitz was a family by the

name of Bloch. They had three girls, of which Haya was older and

Hana a younger. Before the outbreak of the war, Haya married and

conceived a child. She was a member of the local council

("Deputat") during the Russian occupation. Two weeks after the

place was taken by the Germans, the police, already organized by

the German representatives in the area, decided to arrest all

those active in the old regime and to execute them. The policemen

came to the Bloch home and asked for Haya. The young Hana

understood immediately what they were after and said that she was

Haya. They caught her, tied her up, tore her clothes and took her

naked through the town. After a long night of torture, she was

executed. (Now the highschool in Dokschitz is named after her. In

times of celebrations and festivities, she is remembered as one of

the schools heroes, having given her life for the life of her

sister and son. The story was told by survivors from

Dokschitz).

There were a few contacts through local

gentiles, in exchange for a lot of money, or through Judenrat

representatives from other ghettos whom the Germans forced to come

to the county center. There were no contacts with the outside

world. All radios were confiscated. People did not receive news

papers and knew nothing about what went on in the country and in

the world.

The Children in the Ghetto

Little children were also force to wear the

yellow patch. It was a gloomy sight, those five-year-olds with a

patch. There were no kindergartens or schools. No medical aid was

given save the small hospital which only operated for a short

time. Only a small number of Jewish doctors took care of the

ghetto children. The children were the ones who suffered most from

the terrible conditions and the hunger. Children over the age of

12 were force to do hard labor and children under 12 suffered from

the fact that their parents worked and could not care for

them.

All kids looked old for their age because of

the troubles they went through and the worries they had, specially

the girls, wearing long, torn, black dresses and black head

covers.

In the town lived two or three families that

had converted to Christianity decades before the war. They lived

like Christians, but were put into the ghetto nevertheless, in the

end of 1942. However, with the help of Christian friends, they

disappeared from the ghetto and remained alive.

Rebellion, Underground and

Partisans

There were a few escapes to the forests from

Sharkowshtshisna, and later some returned because of German

promises to the Judenrat that the returning would come to no harm.

People escaped from adjacent ghettos as well, but the Jews were

forced to return because of threats and lack of help from the

local population. Once, escapees from a ghetto met a group of

Russian escaped prisoners. The Russians robbed the Jews. Also, the

prisoners threatened the Jews that they would kill them if they

tried to join them so they wouldn't lead the Germans to

them.

At work, exchanging merchandise with the

neighbors, a rumor circulated that groups of Red-Army soldiers

appeared in the forests. They were reputed to be well dressed and

well armed (meaning not prisoners, but real soldiers). The

soldiers promised the population that the day was near when the

Red-Army would be back. They even paid for the food they received

from the people. The population's attitude towards them was

reserved, but sympathetic. The reason for this was the evident

continuation of the war and the cruel treatment of the

Germans.

My friends at work and I received a

verification of this rumor when the Germans posted announcements

and pictures of "bandits" still at large, with a German threat of

killing anyone helping them. The Germans published propaganda

against the partisans. Articles about German victories against the

partisan groups, etc. The result was quite contrary to German

expectations: The population understood, and so did the Jews in

the ghetto, that an armed underground movement was forming.

One day, late in May 1942, I was standing

not far from the press and I noticed a fellow who, by his looks,

was not Bialorussian. He asked me about my work, the situation in

Gleboki, etc. I understood I was talking with someone in contact

with the partisans, and although I suspected that he could be a

German police spy, I took a chance and told him what went on. He

asked me for a number of papers proving a place of residence, a

sort of substitute for the German identity cards. I gave him what

he wanted and he promised to return in a couple of days. He also

hinted about groups of armed men lurking by. He said if I happened

to run into them I should say I was a friend of Fiodor's. The man

did not reappear but I decided to obtain a weapon and run away

from the ghetto.

The Second Slaughter in

Gleboki

In the beginning of June 1942 a group of

Germans arrived in Gleboki. 10 to 12 men from the security

services. Their uniforms were different that the ones of the army.

They wore black ties and there was a sign of a skull on their

hats. These were professional killers, executioners. It was noted

that even the German soldiers and police treated them with fear.

The policemen told the Jews that these new ones had limitless

rights and could do whatever they liked. A rumor circulated that

they came to exterminate the ghetto. They often visited the ghetto

and the Judenrat. Once, when they left the ghetto in armored cars,

the rumors were that they exterminated a ghetto in a small town.

They drank large quantities of wine and gave the clothes of the

murdered also to the police and to people who took part in their

parties. A few days later, they left the town, not hurting the

place. The locals breathed again, relieved, but not for

long.

On June 16 they were back and on June

19th

when the Jews were waking up for work, a group

appeared in the ghetto and ordered the Judenrat to gather all the

Jews in the market outside of the ghetto, near the Jewish cemetery

for a count. The Jewish police announced this and hurried people

out to the streets with their children and small bundles of

valuables and food. In this time there were many who had built

shelters and hiding places in the ghetto but the majority had no

time to use them, and many did not know of their existence.

That day, June 19, 1942, at 10-11 a.m. the

workers being near the press, I heard shots and bursts of machine

guns and I understood what went on. The town was ghost like. No

one dared go out.

At 4 p.m. my younger brother, Itzchak

arrived at the press and said that the whole family had gone to

the so called count. My mother told my brother to run away and

come to me.

Towards the evening I returned to the ghetto

by a side road through the fields to see if anyone was left of my

family. On the way I met two women holding big bundles, speaking

Polish with each other and telling each other about what had

happened. I recognized one of them for I had gone to school with

her son. This son was one of the policemen in the local police. It

seems that the son knew beforehand what was to occur and advised

the women to profit from the Jews' things. When she saw me she was

shocked for a minute and then started to scream: "Why didn't you

report with the rest of the Jews?" I did not answer and walked

away.

When I arrived in my parents house in the

ghetto I found the door open. The apartment was empty. A neighbor

came in and said she was also in the "count". There was a German

sitting at a table. Everyone had to pass in front of him and he

separated them right and left. The group on the right was told

they'll be going to Borisov or Warsaw to work. From this big group

small groups were taken by German and local police and by S.D. men

to the Borok grove - and from there the shots were heard. More

than three thousand people were executed on that day.

The next day the Jews were ordered to go to

work and when back they told that the German employers pretended

innocence saying: "What is going on with you, this police really

isn't good"! But in most cases the Germans were crueler. They beat

the workers saying they would soon be next. The bodies of the dead

were left uncovered for two days and after covering them, a wagon

was brought with clothes to the Judenrat. The clothes were

distributed among the needy. Many recognized their relatives'

clothing. Among the local police, one of the most inhuman was my

neighbor, Taragonski.

How I Came to the Partisans

About a week after the second slaughter I

met an acquaintance, my age, from the town of Dokschitz. His name

was Shlomo-Tuvia Warfman (today residing in Israel, in Akko). He

told me he escaped from Dokschitz after hiding in a cellar for a

few days. Then, he reached a small grove among the swamps. Not for

from it stood a lonely house and in it lived some well-to- do

farmers which supported him.The son of the farmers, who knew my

friend and me since before the war, worked as a foreman on the

road in Gleboki. The Poles, at that time, also suffered cruel

treatment from the Germans. They helped Warfman with food and

clothing. I found out that I knew the family as their son,

Stanislav Lochovski, went to secondary school with me. It so

happened that a couple of days later I was walking from the ghetto

to the press to work, I met Stanislav and greeted him. The pole

was shocked, it seemed, but said to me: "Come to me, bring some

money. I have arms for you". I told Warfman about this and we

decided to go from the ghetto to Stanislav and ask him for

weapons.

One rainy night, my friend and I took a

board from the fence, left the ghetto, and put the board back so

as to not be found out. We went out towards the swamps, to the

secluded house which was 15 kilometers away. We went according to

a map I had found in the press and had memorized before. We went

through fields and crossed the railway. This was very dangerous as

the railway was heavily guarded. After midnight we reached the

house. The Poles opened the door and had us enter the attic of the

stable. In the morning, they brought us coffee, milk and food

(this was the first time in over a year that I ate a regular

meal). During the whole day we remained in the stable. Before

sundown the family brought a rifle with† one bullet

and a

revolver with nine bullets. Stanislav said that the gun belonged

to one of the "Blue Division" (volunteer Spaniards, helping the

Germans). He found the gun on the road.

We had with us only a small sum, three

hundred Ruble. However, we said it was all we had and the family

gave us the weapons. We were left with no money.

We stayed at the farmer's house all day long

and at night we returned to the ghetto. On the way back, near the

ghetto, we were lost because of the dark and we stumbled upon the

barbed-wire fence. The guard, it seems, noticed us and ran towards

the noise, but we hid among some nearby bushes. When the guard

returned we went on. We reached the ghetto gate and found the two

stones we had left as a sign near the loose board. We returned to

the ghetto the same way we had left it. In our house we had a

cellar where we hid the weapons. The men of the house, seeing us

return, were frightened to see the weapons. We warned them not to

say a word to anyone. The absence from work and the overly

populated neighborhood near our house caused the rumor to reach

the Jewish police. I hid the weapons in a better place and moved

back into the house near the press. My brother and I slept in the

storage room near the house outside the ghetto. Although I had to

go to work, I did not since I knew we would be running away in a

few days. In the Jewish police it was decided to quietly

confiscate the weapons and to, somehow, get rid of us, saying the

Germans could destroy the whole ghetto because of us (although the

Germans did this without reason anyway).

Once, while my brother was sleeping, two

Jewish policemen came, took him to the Judenrat cellar, beat him

and demanded he give the weapons. He said he knew nothing. He was

released after 24 hours and I was called to present myself. I let

it be known that I would not come and that if, indeed, they tried

to arrest me, I have in my possession a hand grenade... The

Judenrat men were scared the Germans would find out about the

weapons and backed off. So, except for the Germans, the Judenrat

and the Jewish police also became our enemies. They interfered and

threatened at any attempt to revolt or escape from the

ghetto.

In July 1942 two Jewish partisans arrived in

the ghetto: Zalman Friedman from Dolginov and M. Friedman from

Postawy, after having resided in Dolginov in the time of the

Germans. Since it was known in the ghetto that Tuvia, my brother

and I had weapons, these partisans were also told. They invited me

to the ghetto and said they belong to a partisan group and were

sent by there leader to obtain false papers, watches, money and

leather for boots and shoes.

They also said they would be willing to take

in some young Jews in case these had weapons, as this was a

imperative condition with the partisans.

The commisar of the Soviet partisan regiment

was a Russian named Ivan Mitveivitch Timtchuk, a friend to the

Jews. The envoy, his helper, was a young Jew by the name of

Abraham Friedman (now living in Hulon). The partisans agreed to

take me and Tuvia, but would not take my brother who was only 15

years old. I talked it over with my brother and we decided that I

would go alone and when I reach the platoon, I would ask the

commander, in person, to let my brother join. The partisans agreed

to take my friend, Milchman Zalman, although he did not have a

weapon. We acquired some money and at night, left the ghetto - a

group of about 10 men, most armed, and some being relatives of the

Friedmans'. We reached a small village where a partisan contact

man lived, hid there during the day, and during the night arrived

at a swampy area near the Nevery Kriganovka village where we found

about 25 Jewish partisans and about 600 Russian partisans with

their leaders. Platoon equipped with arms, guards and a

reconnaissance patrol. Sort of a small regiment of

partisans,wearing rags but with a high moral and ready to fight.

Some were commanders that had hidden in the forests or in the

villages since the beginning of the Nazi occupation. Some escaped

from jail. Some wore German uniforms and uniforms of the local

police. The regiment doctor was a Jew from Minsk, Stcheglow, a

major. There were nevertheless partisans who laughed at their

Jewish peers, but the influence of the doctor and the commisar

were a restraining factor.

Moreover, many Jews knew the area very well

as well as some of the locals, and this was a valuable asset to

the Russian partisans since they did not know the area nor the

people although the attitude towards them was friendly. The

partisans told of successful ambushes and raids from the past -

winter and spring 1942. I remember a story about a successful

ambush near the town of Ilia. A convoy of about 40 local police

was destroyed there. Also, there would be groups of saboteurs

leaving from this regiment to blow up German trains.

Companies from that same regiment would take

off at night to a distance of 30 to 40 km and blow up bridges on

roads and destroy small police stations. The regiment had many

contacts in the villages. The food and horses were obtained in the

villages. Sometimes the Germans would murder the whole family of a

collaborator with the partisans. The raids were very quick. They

were done after careful planning and far from the main base in

order not to have the Germans suspect the place.

The regiment had a special unit of about

four men, a sort of interior/exterior security service. In the

beginning of the operations they would pass quietly through the

villages, since there were many informants to the Germans. When

the regiment grew and there was a need for more supplies and wider

reconnaissance, it became impossible to hide the existence of the

regiment (it's name was "The Avenger"). The informants in the

towns post a serious threat to the existence of the unit, and

after an informant informed, German formations would storm the

villages. Of course, the searching was useless, since by the time

an informant reached the police and by the time the German police

was organized, the partisans were tens of kilometers away.

Finally, the regiment commanders found an ingenious solution. They

gave an order to pass through the villages at night, cause a

ruckus, to "make an impression" and to show off to the natives as

if there were many more partisans than there actually were. To

show they were a force to contend with. Many of the partisan

contact men and agents were sent to local police stations with

news of partisans. This attained two objectives:

A) The contact were trusted by the Germans.

B) Cases were invented, and five or six

informants would come from different directions to confuse the

Germans.

The Germans could do nothing and did not

know which direction to take. The German leaders would become

angry and started beating on the informants, some of them being

real informants with genuine information. In a short while the

Germans themselves stopped the flow of informants and prevented

themselves from receiving any information about goings on. Indeed,

the partisan regiment began moving around freely even in the day

time. The partisans had exact information as to German police

movement. The Germans were forced to move only in large group for

lack of information and fear of ambushes.

I know of a partisan ruse using two Jews.

Two Jews were sent in the morning to Swir village, 2 km from a

strong police station. They pretended to be drunk, badgered the

local and asked them for money and Vodka (there was a standing

order in the regiment which forbade robbing and mistreating the

local population). One of the villagers, a collaborator with the

Germans, ran off to Swir to say that two Jews are terrorizing the

village and it would be easy to capture them. The Germans, hearing

this, were raging. They mounted their horses, some without

saddles, and laughingly planned how they would torture the

despicable Jews. At that time a partisan ambush of more than a 150

men with machine guns lay on both sides of the dirt road.

When the commander saw the informant run

towards the town he was happy and said: "We did it!" Even the

partisans were not aware of the plan and the patrol unit wanted to

shoot or arrest the man running to inform. A half hour later the

group of horsemen came to capture the Jewish "bait". Twenty of

them were killed immediately by the cross fire from the ambush.

The company commander was Markov, a local Russian married to a

Jewish woman. The "bait" was his idea. The incident and it's

enormous success, as well as a catch of weapons and equipment, and

the bait idea made the Germans a laughing stock in the whole area.

This happened in spring 1943.

The German cruelty towards the local

population, like the execution of hundreds of villagers (there

were no Jews left in the area), the burning of whole villages and

houses with their residents (the Germans would force the locals

into a house and set fire to it with them inside), caused the

population to rebel against them. The partisan regiments changed

from hundreds of men to brigades of thousands. There were areas of

hundreds of square km where the local authorities were not German.

The Russian army command sent hundreds of paratroopers with

automatic rifles and radios to the German rear in order to

strengthen the partisan movement and train it. It reached such

proportions that there was a temporary air field in the German

rear where even Russian planes would land. This occurred from the

end of 1942 to the middle of 1944.

A special emphasis was put on local

propaganda. Airplanes with military equipment also brought

newspapers and bulletins. The partisan leaders would hold

assemblies in the villages to explain themselves to the

locals.

Near the swamp area was a small Jewish town

near the Narotch lake. There was a Jewish ghetto in this town made

up the town Jews and Jews from nearby towns until November 1942.

There was also a gendarmerie station in the town and a platoon of

fascist Lithuanians was stationed there. It was decided to attack

the town and exterminate the gendarmerie and the fascists. The

Jews in the partisan regiment were concentrated in one platoon,

the third platoon. The commander of the platoon was a Jew by the

name of Jacob Sigaltchik (today living in the Magshimim settlement

in Israel). It was decided that during the attack on the town, the

ghetto would be released. The attack took place on the night of

November 9, 1942.

Not all the fascists were killed, but some

were, their positions were burned and above all - the ghetto was

released. Thanks to this, about fifty people were saved, most of

which are living in Israel today.

After the releasing of the ghetto, the Jews

were settled in the heart of the partisan area and remained there

until the place was liberated. In December 1942 the partisan

leadership decided to organize an underground press. I was sent,

together with a group of partisans, to the Gleboki ghetto, to

break in during the night and obtain the necessary materials for

printing. I knew the place and also knew what to take. The

operation was handled with a quiet entry to the town and the goal

was reached.

In the beginning of 1943 hundreds of

newspapers and leaflets appeared within a radius of hundreds of

kilometers. It should be noted that in 1943 local policemen and

Ukrainian fascist troops also began defecting from the German

service. They went over to the partisans. The regiment succeeded

in many ambushes, in putting mines on transportation routs and on

railways, and in attack on German posts. In the summer of 1943 the

Germans planned an all out attack between Kursk and Oriol. On

orders from the general headquarters, all partisan regiments took

to the railways and blew them up all during one night. The

partisans called this "the rail war". In the midst of the German

attack on the Russian army, their transportation was cut off from

Brest (The Polish-Russian border) to Smolensk, a distance of about

a thousand km. This caused the Germans a stoppage of supplies in

the midst of the attack.

In the summer of 1943 I found out that there

were still about 2000 Jews left in Gleboki. With the permission of

my commander, a group of Jews, including my brother, was taken out

of there. These, later fought with the partisans. My brother,

despite his young age, was a brave warrior and was greatly

appreciated by the partisan commanders. Many of the Gleboki ghetto

people got hold of weapons. Some ran to the forests and when this

was known to the Germans, they decided to exterminate the ghetto.

They did not enter the ghetto for fear of resistance, as the

residents had weapons, and so surrounded the ghetto and bombed it

with fire bombs. The houses were built of wood and the ghetto went

up in flames and with it went it's people.

The Germans understood that the partisan

movement posed a strategic threat to them and so took out of the

front lines a few divisions and besieged wide areas. They would

burn the villages to impede the partisans from receiving

food.

They bombed the forests with fire bombs, but

thanks to the partisans' vigilance and knowledge of the area, they

succeeded, in most cases, to break through the ring, before it was

tightened. Small groups would be left in the forest in order to

deceive the Germans. They would make much noise and convince the

Germans that they had the main force.

In a German "purge" during May-June 1944 my

regiment broke through a German ring. My brother was in the

leading part, while I stayed with a small group, within, to create

a deception. The regiment, indeed, broke through but suffered

heavy losses and scattered (the order was to reassemble near

Borisov, next to Zambino, on the banks of the Berezina, in case

were were dispersed). The single groups were caught over and over

in German ambushes and reached a new gathering place without

leadership, without food, with wounded and sometimes - without

weapons.

I was told by one of the partisans with my

brother, that the Germans surrounded them in the forest. My

brother was already hungry and barefoot for a few days and when he

understood the Germans might catch him he began shooting at them

and, by doing this, of course, showed where he was located. When

he ran out of ammunition, he laid down on a hand grenade and when

they came to capture him alive, he himself up with them.

Inside the German siege, our group shot from

many different places in order to lead the Germans into the

forest. The group moved from location to location and stayed near

the Germans at all times, however, the Germans could not capture

us. They shot in the forest in complete chaos, for fear of the

group, but doing this they showed us where they were.

Two days later they understood their mistake

and the forest was in utter silence. The partisans from the

deception group decided two days later what this silence meant. I

was sent with another partisan on reconnaissance. We walked in the

forest parallel to the road and checked 5 km. We found nothing

suspicious. We tended to think that the Germans had left. When we

returned we found fresh footprints of German spiked shoes. My

friend left the road and entered the bushes while I began to check

what was happening. When I turned around I saw three Germans

sneaking behind me, one of them only three meters away with his

hand extended to grab my gun. I jumped to the side and ran between

the bushes. The Germans fired, entered the forest and kept

running. Our group heard the shooting and thought my friend and I

was shot. I lay in the mud, among the bushes, until evening, and

at night joined my group.

A few days later the Germans discontinued

the siege for the following reasons: The Russian attack on the

German army was developing; There were rumors about a second front

and about the ally invasion of Europe.

In July 1944 the German army began it's

retreat. Many of the German police and other Germans remained in

the forests and were surrounded by the partisans. So the roles

were reversed. The Germans went into Russian captivity by the

hundreds. They feared partisan captivity which meant - death. I

saw hundreds of Germans take to the streets with their hands

raised, asking army units to imprison them. The Russians were so

sure of their victory that they did not even bother capturing

them, and only showed them the way east towards any town, where

there was a garrison to handle them.

The Russian army was very humane to the

German, despite the partisan anger and the population which

demanded lynching.

The commander of the local gendarmerie and a

local German, part of the German police, were caught near the town

of Miadel. The Russian army command tried them publicly. Locals

whose family was tortured and killed by these two testified

against them. They were hanged after the verdict was announced.

The locals came in masses and clapped when the verdict was read. A

number of local Jews, back from the forests by now, did not

attend. It is said that two Jews, there, were in tears seeing

these murderers swinging from a rope.

1944. When the Russians liberated the area,

many people joined the Russian army, but many partisans were

offered posts with the local authorities. I had no family left and

so joined the Russian army. After a short training, I was sent to

the front lines and took part in the Visla river crossing and the

battles for the release of Shlesien. Together with the regiment, I

took part in the Oder-Nisse crossing and in battles in Poland and

Czechoslovakia, near the city of Glatz, in the battles of the

Sudeten land - and so I arrived in Dresden in Germany. Across the

river we could see the ally armies. The war was over but despite

the German surrender, there were Ukrainian and traitor Russian

Platoons (from the Vlassov army) still fighting. My regiment took

part in the extermination of these bands. I stayed in Germany for

a short amount of time and them returned to Russia. At the time

the Russo-Japanese war had begun, but my regiment stayed in the

Kaukas.

I fought with the Russian army from 1944

until the beginning of1946. I received medals and a high honors

from the Russian army for my diligence in fighting the Nazis and

for fullfiling my duty. On the way from Germany to Russia my

regiment passed through Auschwitz and I then saw the piles of

ashes and bones, the shoes, the glasses and ruins of the gas

chambers and ovens.There were other Jews in my regiment, some of

which had excelled in fighting the Germans. An artillery regiment

was attached to my regiment under the command of a Jewish major by

the name of Kaplan, holding the highest honor of the Russian army

- a golden star and the title: hero of the Soviet Union.