|

[Page 340]

Ciechanow Jews in Auschwitz

The last days in the ghetto prior to the final liquidation destroyed the city and we built the new city. We believed that they would not send us out because all the males from the ages between fourteen and sixteen, and females between fourteen and fifteen, worked, and were registered on jobs. But apparently the murderers didn't have enough blood and the turn of the Ciechanow Jews came.

It was Shabbat morning in the last days of October, 1942. I lived on Tilsit Street at that time (once called Shlonska) when my neighbor, Shalom Stolnitz, came to me, with a deep sigh and tear-filled eyes, and said to me: “All the Jews who find themselves in the Ciechanow area must leave by November 1.”

We immediately understood what this meant. It is a death sentence. I went outside and saw how everyone was going about, wringing their hands and crying. Desperate cries were heard: “Jews, let's not leave. Better we should die here.” With the help of the Judenrat, however, the Germans succeeded in filling the transports. One transport of one thousand, five hundred people capable of hard work were taken to Aubershlezia in November 1942. Those in that transport were: my mother, sister, my bride's brother, parents and myself. There was talk that this was supposed to be a “good” transport that is headed for work in the factories.

We traveled for two days. The crowding in the wagons was so great that there was no room to stand or sit. We received no water. Since everyone still had something from home, it was a little easier to survive.

I saw how they were led to the gas-chambers

Friday morning, November 9, 1942 we left Ciechanow. On Saturday, late in the evening, we reached Auschwitz. We all shuddered when we saw that we are totally surrounded by Gestapo and by dogs. We heard their mad shouts: “Raus fun di vogn ir hunde!” (Out of the wagons, you dogs).

[Page 341]

I saw how a Gestapo man threw out through the window my friend Wolf Kostsheva's two children.

There is great shoving. Beatings are being administered from all sides. A wild scream is heard: “Leave the bags on the ramp. Men, women, children separate!”

An Obershturmfuhrer stood and pointed with his hand: left and right. Ten minutes later four hundred men and a small number of women went to a lager. Nine hundred people, including two hundred women, the Germans loaded onto trucks and took them to be burned. Amongst them was my mother and my bride's parents.

The murderers lined us up, five to a row, surrounded on all sides by S.S., and in this way we were led to the lager.

At one o'clock in the morning we reached the lager. We were led into a large room. Immediately block leaders came, and to assist them block elders and kapos. Blows came from all sides. They shouted: “Hand over everything you own! In five minutes everyone must be naked. Money and all other valuables must be deposited in the containers that had been pre-arranged. Shoes and underwear you must throw into one heap.”

This had to be done immediately, quickly, because the kapos were going around amongst us with thick sticks and murderously hit those who didn't want to undress.

My hair was immediately cut off. There was no bath nor water for washing oneself. A pair of shorts was tossed to me, with a small jacket and a shirt. As soon as I put it on it tore. I also got something for my head but it was too small. I got wooden clogs that didn't fit and wouldn't get on. For requesting a larger size I got struck with a stick. From all this I understood where I was.

They counted off a group of fifty and handed us over to a block-elder, a tall, strong fellow, with a wild look in his eyes and a stick in his hand. The sleeves of his shirt were tucked up, his collar undone. His whole body and his hands were covered with tattoos, like an old criminal. His name was Albert Neiman.

He led us into a barrack with an open roof that let the rain in. The windows were also open. He divided us so that there were ten of us in a section. Some got a bit of straw. Most of us slept on stones. We didn't get any blankets.

[Page 342]

Each one was occupied with his own tzores, with what awaited him. One could hear sighs and painful cries: “My wife, my children, my mother.” I myself lay on the asphalt for hours and cried: “Woe is me, my mother is being gassed and burned, and possibly I will also end up that way.”

Then we heard the mad shouts of the block-elder and his helpers: “Get up. Outside for roll-call.”

It was dark, four o'clock in the morning. We were chased from all sides. I couldn't grasp what was happening. In order to avoid getting hit I also went out.

We were lined up ten in a row. The mud reached to our knees. It was raining. I had lost one shoe. My jacket had no buttons and it was open. The rain poured non-stop, and I was shivering. I regretted that I didn't go with my mother and all my acquaintances. Why should I suffer and be tortured to death.

We stood for more than an hour and they tortured us with commands; “Stand up, get down.”

Finally, seven o'clock in the morning a block-leader showed up. We were brought back to the same room where we had been the previous day and there we were called out according to the letters of the alphabet. Since my name began with an “S”, I stood until nine o'clock in the evening without food or water. Around ten o'clock I got two potatoes and a bit of cold water. Before I started to eat I heard a shout: “Out of the block, line up in fives!”

One hundred and twenty men were taken into Block 16. There I found many Belgian Jews, very honest people, mostly older people, between twenty-five and forty years old. All together in this series: 71.000. The block-elder was a Jew by the name of Mandek from Warsaw, a “Narvikher,” his representative, Yosele, from Radom. His “specialty” was to give “25” with a thick stick on the behind. Whoever got hit by him didn't go to work the following day because he was carried off to the “sick-bay.” That's how hundreds of people were led to their death by him. He was shot in 1943 for trying to bribe a block-leader.

The first night in the new block, as soon as I fell asleep, screams were heard immediately: “Get up!” It's three o'clock in the morning and I quickly dressed. We were called out for roll-call that lasted until seven.

[Page 343]

After the roll-call we were surrounded by kapos and foremen with sticks in their hands. We were grouped into komandos. I ended up in the komando: crematorium number 1. The kapo was a German, dressed in a Russian winter coat with a stick in his hand. He was called Hercules. He had four Polish foremen, four actual bandits.

We came to the “work-place.” There crematorium No. 1 was built. The kapo called out all the new arrivals. I wanted to approach but a Polish Jew grabbed me and held me back. I didn't know why, but I soon understood that this Jew saved me from certain death. The kapo gathered 25 Jews (French and Belgian) and told them to sing loudly. Then he and his foremen chose 16 Jews and declared: “Since they sang so well, they'll get good work. Meanwhile let them rest.”

Before lunch each one got a pail of clay and they were told to go up high where the chimney of the crematorium was being built. This was a small narrow space surrounded by boards. I stood below where the cement was made, where I would observe everything. As the Jews were going up and hanging onto the boards, the Polish foremen, who were standing on either side with a hammer, hammered quickly and the boards broke down. All 16 Jews with the pots of clay in their hands fell and were killed on the spot. The kapo and his foremen laughed uproariously and let it be known these are Jews who had never worked and therefore they fell down.

The murderers immediately commanded Jews to drag away the dead ones. At work one also got killed. The other Jews were cruelly beaten.

When we returned, the Jew who had saved me told me that every day they do the same. They command that Jews sing, noting at the same time who has gold teeth…Then they are sent up high. They fall down and the Polish kapo aid pulls out their teeth together with flesh, using pliers. This is turned over to the S.S. For this the kapo gets schnapps.

[Page 344]

I got into the komando of Barrack B. There it was somewhat better. I met a French Jew from the 53.000 series, whose name was Moritz. He helped me a lot. Later I worked in Birkenau.

The suffering from hunger was terrible. We would stand at roll-call two or three hours. In the evening we got our midday meal at the workplace, where the mud reached to our knees because the ground was like clay. When I put down a foot, I could hardly lift it out again, with great difficulty. We had to eat standing, 10 people in a row, in order that a control should be possible to assure that no one gets fed twice. There was no water at all, and the bowls were dirty, full of mud.

When we went into the block we had to quickly get up on our sleeping bunks. At night, when we would fall asleep from exhaustion, a piece of bread and 10 grams of margarine would be tossed to each of us. But the block-elders cut this in such a way that the largest portion was always left for them. Each of us was lonely and it was deathly risky to go to someone in another block. If “a stranger” was found there he would be killed immediately.

*

I already wanted to accompany them but I wanted to see my sister and my bride at least once more. I found out that they work for a komando “S.S. - Unterkunft.” There they have very mean Polish kapos and foremen. Beatings go on all day. If a Jew comes to them from anywhere, they finish him off immediately. In spite of all this, I went to that komando.

I met my bride and sister in Auschwitz.

[Page 345]

On November 18 komandos were going out as usual. We came to the gate. The music played according to the beat of the komando: Mitzer up, hands down. We enter, like the proudest soldiers.” Our hearts were beating because who knows: he will be sent back dead and he will no longer hear the sad music. Finally we reach the stand. My heart beats with joy yet with sorrow. Finally I will see them -- my sister and my bride. I didn't eat the piece of bread. I gave it to the foreman so that he would take me with the group that works together with the women.

To the women whom I knew from Ciechanow, I had already given a sign to tell my sister and my bride, who stuck together, that I'm present and am working as a paver.

Finally I saw two young women dressed in men's uniforms of Russian prisoners and in their grim top and trousers. Their hair was shaven, heads covered with a kerchief. On their feet -- one wooden shoe and one rag-sandal. Their faces were pale and thin. Their eyes looked at me sadly. When I saw them from the distance my heart started to beat faster. Tears started to flow from my eyes.

I didn't want them to see my fallen spirits, so I scratched my hand with something so that the physical pain should disguise my inner suffering. They couldn't approach me because this was asking for death. However, they did notice me wiping the blood off my hand with my cap. They removed the kerchiefs from their heads, tore them in half. With one part they again covered their heads and in the other half wrapped a piece of bread of 20 grams and a piece of turnip of 10 grams. They passed this to me saying: “Take this, Laibl. We have enough. Hang on. Better days are coming.” My sister wanted to say something else, but the S.S. appeared and she immediately went away.

I followed them with my eyes and I wept. I didn't cry so much because of my own condition, but because of their suffering. Who knows, I thought, whether their suffering is not in vain. It was then that I decided that as long as they live, I also must live.

I avoided seeing them for two reasons: first of all, I was told that they always carry half a loaf of bread that they don't eat themselves but want to give to me. I didn't want to take this. Secondly - Khana, my bride, asked me why her brothers don't come to see her and I didn't want to tell her that they are no longer alive. The younger brother, Maier, was murdered in the komando of crematorium No. 1, and the older one, Motl, volunteered for Block 7 -- the death block.

[Page 346]

Sad and difficult days passed. Every day there remained fewer of us. It is difficult to describe the hunger. I grew thinner and thinner from day to day. Another terrible enemy appeared -- lice. Since there was no water we couldn't wash. The lice multiplied, and we couldn't sleep. We struggled with them throughout the night and couldn't find a solution.

During the first days of December, 1942, I worked on the construction of crematorium No. 3. That day there was a frightful kapo: a German, with a red insignia, called Max. When he was drunk he would lash out at anyone who came his way. One day he killed two people with a spade. They were both people whom I knew from Ciechanow. One was Steinberg, the second, Kzivansky. I was very despondent and tired because we Ciechanowers carried them back from work. This was the last honor that we could give them.

No sooner had I fallen asleep when I heard shouts in the block. We're being chased to the roll-call, driven with sticks. I went out naked. A terrible snow storm was blowing from all sides. The frost was burning. I didn't know what happened. Finally Yosele, the kapo's helper, came and said: “We want thirty of you men to load the dead onto the trucks, and if you don't provide this number the whole block (all of you) will stand out here until the trucks will come. This will take another three hours. If volunteers come forth we'll allow the block of people to go back in.”

Nobody wanted, after a hard day's work, to load, at midnight, the dead, and to get up pre-dawn to go to work after that. But what could we do? In the lager one doesn't ask such questions. Thirty men volunteered and I was amongst them. We loaded 800 dead. So it was every day.

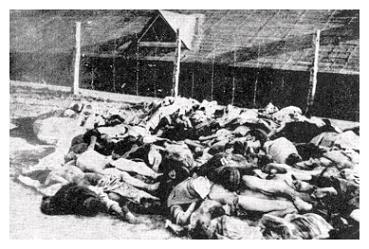

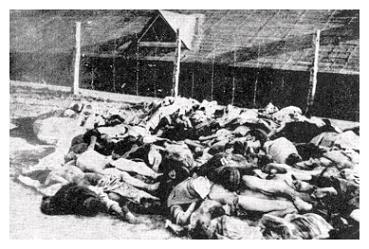

Later a block-leader chose twelve men. I was also amongst them, and we were led to the women's lager -- Block 25, where we were instructed to remove the dead. This gruesome picture that I saw there remains before my eyes to this day. I seemed to turn to stone and didn't know what to do. Approximately 70 women, mostly Dutch, lay in a state of dying. Mice were eating them, sucking their living blood. An S.S. man with a thick stick stood there and shouted. “Raus mitn drek!” (Out with this garbage). “Put a move on -- if not” – he struck with his stick on our heads -- “you'll go together with them.”

[Page 347]

|

|

|

|

[Page 348]

blank

[Page 349]

|

|

|

I hold a leg. It's impossible to move them because in their expiration they are grasping hands. I have no strength so I stand up. Then I got struck with a stick on my head. I get covered with blood. Binyamin Zigmund noticed this. (He was from Ciechanow, who was killed while working in the lager). He said to me in Polish: “Give me your hand and I'll help you. If not, he'll kill you.” Finally I succumbed.

My acquaintances wiped the blood off me with snow. I pulled something out of a sleeve and wrapped the wound. It was too dangerous to go to a doctor. For uttering the word “sick” one would immediately be burnt. For not going to work one would also be taken immediately to Block 7. Those were the difficult days that I lived through in December, 1942. It's no wonder that from our transport more than half had by then perished.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ciechanow,

Poland

Ciechanow,

Poland  Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 2 July 2003 by LA