|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Page 5]

The “Memorial Book” of the Community of Briegel and its Environs

by the Coordinator of the book

(Hebrew version)

I was not a native of Briegel, yet I personally feel like one who comes from that small town. Because from my earliest memories, I remember myself in Briegel. There I grew up, I suffered, and became an adult, until I immigrated to the Land of Israel. As such, I feel the unique past of its Jewish, Chassidic community life, with its social, national, and communal problems.

I can still see the “little Esthers”, “little Sarahs”, “little Channahs”, with their disheveled hair and the sad look in their eyes, glowing in their beauty, as they are running from primary school, to play hopscotch and Jacks.[1] And here, before me, I see the boys of the “cheder”[2], the “little Avremels”, “little Moshes” and the “little Shlaymes” with their curled sidelocks, returning from their “cheders” on dark winter nights with their candle lanterns that lit up the dirty, muddy streets of the town. They attended the “cheder” to assume for themselves, the yoke of Torah. I see before me, those delightful girls who dream of their desired bridegrooms and so too, those young men who attend the small study houses, “the advanced” and the “populace”, who desire and covet the building of a family home, that they are unable to achieve.

I see before me, the elderly, who rise early in the winter to do their morning duty, who cling to the white-hot oven and say psalms before reciting the morning prayers; and they sigh every year about the severe winter, the likes of which they cannot recall. Thus, I see before me, all those small traders waiting impatiently for a customer, and all those drivers of horse drawn carriages, lacemakers, and others like them, who struggled to earn a living, yet on the Sabbath, there was always something lacking.

I see standing before me, all the tradesmen, tailors, hat makers, shoemakers, carpenters, metal workers, painters, glaziers, and all other kinds of “makers” who struggle so hard to provide for their families; I see before me, the Rabbis, the rabbinical judges, the ritual slaughterers, the beadles, and the teachers who instilled in us, so much love for Israel and Judaism. So too, I see before me, those “intelligent people” who did not even want to contemplate, what was likely to happen to them. I see before me, the Zionists of different kinds, who express themselves eloquently, without fulfilling personal goals; so too I see before me, all the youth movements who believed that they would bring about a revival in the lives of the Jewish community in Briegel and did not achieve their aims. In particular, I see my parents, my brothers, who never enjoyed life in this world, and never sinned, not to God nor to man. As righteous, may they live through their faith!

In my view, the whole Jewish village stands before me, with its synagogue, its prayer houses, bathhouse, “Bet HaAm” (Dom Ludowy), the youth meeting places, and so too, all the neighborhoods by name, and their uniqueness. Oh! All these images pass before me, for years now, and they call and cry out: Do not forget us! Do not forget us! I confess, that more than once, I was tired and despairing when I encountered obstacles and disruptions of various kinds in the town, until they became slanderous, exhausting tales. And the echoes of the cries, do not forget us, reverberated in my head and fluttered in my heart; and my heart overpowered my head and I returned to these thoughts again and again? Perhaps? Perhaps? And because of this? And behold, it arose and came into being – the “Yizkor Book” of the town exists.

I am not ashamed to admit, that among so many “Yizkor Books”, rich and large, our book is not one of creative grandeur in all the explanations because it was not arranged and written by historians, authors, and other skilled writers; in comparison, our book that was the creative product of ordinary people, written by workers, but it is not literature and it is not “”folklore”. We must add (because, in my humble opinion, the literature does not need additions, as that would be superfluous and would lessen its worth) that all we wanted was testimony in writing, to the lives of our parents and the survivors of the Holocaust, to that devastation that was inflicted upon them by Asmodeus[3] the German – their name will remain as a stain on the world.

I believe, with complete faith, that our children and grandchildren will return and free themselves from

[Page 6]

the mind-set of the present-day “generation of the desert”[4], and not be enchanted by the “golden calf”[5] of this generation, and they will see that this testimony will be like a simple monument carved from wild rock, worked with a damaged hammer and chisel, that it is no less than marble monuments, polished and adorned; for in spite of everything, they will not be disappointed or ashamed of it, for it is rock.

Translator's footnotes:

by the Coordinator of the book

(Yiddish version)

I was not born in Briegel, yet I feel like one who was, as my memory serves me, from my childhood.

All this is immersed in my memory, the whole Briegel Jewish audacity, with its social and national issues, and in particular, its specific Chassidism. Even now, the Chassidim still shine before me and in my memory. I remember the elderly Jews who would gather in the prayer house in the winter, sitting at daybreak at the red-hot metal oven muttering their psalms, each to himself, before the commencement of the communal morning prayers.

I look with delight at the little Esthers, little Sarahs, little Chanahs with their disheveled hair and shining beautiful eyes as they run quickly from their Polish elementary school, to snatch a game of “hopscotch” and “Jacks”. I still see before me the cheder boys, the little Avremels, little Moshes, little Shlaymes with their beautiful curly sidelocks, as they return from the cheders[1] where they studied whole days and took upon themselves the yoke of Torah; and in the evenings, they made their way home with their wooden lanterns that lit up the narrow, dark, small streets. I remember the grown-up, charming, delicate, marriageable young women who wait with sad eyes for their future husband. I still see the Chassidic young men who dreamed of a purposeful life… I cannot forget the Jewish artisans: tailors, shoemakers, bookbinders, carpenters, furriers, metal-workers and many others who labored with their hands, who toiled an entire week and never had enough for the Sabbath. I also remember the shopkeepers, the buyers and sellers who traded and wandered from place to place and never managed to make a living for their families. Before me, there flash images of the Briegel Rabbis, rabbinical judges, ritual slaughterers, and teachers, who in their neglected lives, had no enjoyment but taught their community that the main thing in life was piety, study of Torah and worship. Apart from them, I see my parents and my brothers who also wore the yoke of Torah; but remember that “there is no greater joy than the study of Torah” because it is our life and the length of our days, and by it we are guided day and night.

[Page 7]

I remember all the youth of the Jewish social organizations who believed that they would usher a new and beautiful world into the Jewish community of Briegel.

All these people have been standing before me for years and call out – do not forget us! We have shared the Jewish fate in the cruel chapter of our history, in the brutal Himmler period, may his name be erased.

This call occupied my thoughts during all the disruptions that I have encountered on the path to realizing the publication of a Briegel Yizkor book. I regard it as necessary to stress that for many, many, months, I had to eliminate numerous senseless issues that caused interruptions to the activities surrounding this book. I overcame all of this, and with Briegel Chassidic perseverance, I returned to the work, perhaps part of it? I take into account that unlike some of the many valuable Yizkor books, our Yizkor book was not written and compiled by historians and skilled writers, but rather by simple folk and that it should be a worthy monument for our tragically destroyed town. For the people of Briegel, our Yizkor book, will be no less.

I want to believe that our children and grandchildren will free themselves from the present-day “generation of the desert” and its golden calf” nightmare, and that the Yizkor book will become sacred to them – a poor memorial to our tragically exterminated fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, friends and acquaintances.

We too, the survivors of Briegel, do not want to be forgotten and in this way perpetuate our memory.

Translator's footnotes:

Chaim Teller

Translated by Libby Raichman

To all appearances, this small town of Briegel, was like all the small towns of western Galicia, but if we compare it to the small towns in the area, we will find that it is essentially different. It is enough to indicate, that it was one of the few small towns where the Jews comprised approximately 80% of the total population. Furthermore, the Gentiles lived mostly in the suburbs of the town, meaning that the Gentile Poles in the town were fewer in number, and their presence was hardly felt. It is possible that this fact shaped the nature of the town, at the outset.

The town was not industrialized and apart from the largest beer brewery in Poland, in the neighboring village of “Okocim”, there was not even one enterprise that was fit to be called a small industry. In Okocim there was a total of two professionals and their assistants, who were painters and tinsmiths. All the rest of the workers in Okocim were Poles from the village and the surrounds, professionals such as, tailors, carpenters, glaziers, tinsmiths, cap makers, shoemakers, and furriers. The professions of the Jews in the town were, in addition to the above, “makers” such as, bag maker (makers of paper bags), vinegar maker, maker of “kishke” - edible intestines, jam maker, sweet maker, brush maker, and all other kinds of “makers”, even tzitzit makers (those who tied the tassels for prayer shawls and the 4 cornered small, fringed shawls). What was most remarkable was Steinlauf's soap business in Briegel, in which two workers worked four times a year, for a few days. I worked there twice, each time for a few days. In opposition to this enterprise, was the soap manufacturer “Shantzer” in Bochnia, that employed 10 permanent workers who worked every day of the year. Its employment practice and its economy therefore impacted on the social make-up of our town, and for these reasons, even determined our town's unique atmosphere. If we take as an example, this nearby town of Bochnia, whose total population was greater than Briegel, but the Jews there, were in the minority, and they were also less in number, than the number of Jews in Briegel; and this shaped the image of Bochnia in general. The most striking difference between the two towns, was the Sabbath in Briegel. It was possible, not only to feel the ambience of the Sabbath, but also to truly feel how the town donned the glorious clothes of the Sabbath queen, and the whole town was enveloped in the mood of the sanctity of the Sabbath. There was only one Jew in Briegel who allowed himself to desecrate the Sabbath publicly. This was the lawyer, Deiches.

There are many facts of life that indicate what distinguishes Briegel from other small towns, therefore, when Briegel is compared to the nearby town of Bochnia, the uniqueness of the pale of settlement[1] of the Jews in Briegel, is reflected. In Bochnia, on the Sabbath, there was great activity because many of the Jews desecrated the Sabbath in public. Bochnia was industrialized and therefore activity on the Sabbath was more common there, more appropriate, and more accepted by its Jews. Some of the young people found work there as clerks, or in warehouses and shops, of which there were many more than in Briegel. A greater number of people found work in Krakow. This determined their standard of living. A clear sign was evident among the youth, 70% of whom, studied in post-elementary and vocational schools. They spoke Polish and many of them did not know Yiddish at all because their parents also spoke Polish to them in their homes. All these factors defined the social make-up and the character of progressive Jews, according to the ideas of that time. In conclusion, I would state that they lived a lifestyle in Bochnia, like the one in Krakow. In contrast, the people of Briegel were paupers and even beggars. Perhaps a third of the Jews lived comfortably, compared to a third who needed social assistance, and another third that struggled hard to sustain themselves from day to day.

[Page 9]

All this made the people inclined to seclusion and they withdrew into themselves in all aspects of life; the aftermath of this was felt in the life of the town, and it was similar to “Tarnow” in all aspects of life.

The Town's Special Way of Life

I would not be sinning, if I said that Briegel had a lifestyle of its own; moreover, she had enclosed herself in a ring of traditional life for many generations. It is not by chance that Briegel had four Rabbis, each one with his own Chassidic group, and his own style that indicated their process of thought and perception, as if they needed a local perspective, from which there was no escape. Even those who seemingly, thought that they were exempt from the restrictions of the Chassidism that the town imposed upon them, they too, remained captives of the restrictive Chassidic way of life of the town, and only a few individuals broke away from the prevailing atmosphere; but generally, all the residents of the town remained adherent to the way of life in the town.

In Briegel, the Yiddish language was the dominant language spoken by parents and their children, but there were a few families, that could be counted on one hand, who spoke Polish in their homes, as well as a few children who studied Polish in a post-primary school. Indeed, there was a kind of trend in fashion among the young women who were completing their primary school education, to speak Polish. This was however, a phenomenon of the “petty bourgeois”, to speak in a foreign language, which means that they adorned themselves in the feathers of the intelligentsia, so to speak; but this was only lip-service, because in their souls they remained wrapped in the grip of the unique Jewish life of the town - socially, spiritually, and culturally. And this was manifest in all the different types of youth organizations that appeared in the town from 1919 onwards. I would say that the Jews of the town, found their vitality only in the town and from it, and there are many examples in the public life of the town that attest to this.

Reb Ephraim'l Templer in the Town

This Jewish man came to the town after the death of Reb Tuvyele. He was, in a sense, the “good Jew”, in other words, a Jew who conducted himself warmly towards those who turned to him when he prayed to God on their behalf. Scores of communal leaders gathered around him, of whom Reb Moshe Dovid Landau was the most important among them, and they established Reb Ephraiml's prayer house. They prayed there on Friday evenings and on Sabbath mornings only. He himself, was not involved, and did not intervene in any issues that came about in the town. He devoted all his time to teaching Torah and writing commentaries on it. He published two books during his life, and who knows how much written material remained in manuscript form and was never published. Like him, those who gathered around him, did not intervene in any matters related to the community in the town. What they did do, was manifest in their visits to him for the Friday evening meal and on the Sabbath afternoon. On a regular Sabbath, as a “quorum” of 10 men were required for communal prayer, there were 15 who came to hear a word of Torah from him and sing Sabbath hymns. On the more important Sabbaths during the days of the festivals, up to 30 people gathered and there was great rejoicing, particularly on the last day of Passover. I still remember the 5-liter jugs that we sent with a few boys to Avraham Minglgrin, to bring the drink “mead”, made from honey. This was the alcoholic beverage that it was customary to drink on Passover, as beer is leavened food, according to Jewish law, and not permitted on Passover. I also remember the songs of our friend Hersh Yosef Landau who was with us in the Land of Israel, for a long period of time.

[Page 10]

The Wielopole Chassidim

These Chassidim enclosed themselves into a separate autonomous unit, with their own prayer house, and within it and around it, they created their own mode of existence, in all aspects of life. It is worth noting a unique incident relating to the festival of Purim. One of the Wielopole Chassidim, the “Krinitzer teacher”, used to plan a Purim performance every year, by a group that he assembled from among his students. There was a different presentation every year that began with a “Purim Shpiel”[2], a “Binding of Isaac Shpiel”, a “Ahaseurus Shpiel” and a “Joseph Shpiel”. I participated in two of these myself. This was a public performance that was open to all in need and took place in a room of the Wielopole prayer house, a room that measured 6 x 8 meters. It was cleared of all the benches and the “balmar”, as the table was called on which the Torah was placed for reading, and all the tables were gathered to one side of a wall, with their reverse side towards the stage. Except for the table of the Rabbi and his associates who sat around him, all the rest of the space was unusually packed, and whoever did not crowd inside, spread outdoors next to the windows, so that they could see, or at least hear, this “operetta”. (Nowadays, after seeing the play of Itzik Manger and the troupe of Pesachke Burshtein), a few times, I allow myself to say that we were no less able than them. This community that gathered was a varied one, representing all the groups in the town. They enjoyed the festivities very much, because it was part of them, and the students of the “Krinitzer teacher” were boys of eight years old. I was privileged to be one of the leads in the plays, for as the Krinitzer teacher explained, my role was to be the person in charge of the home, the father Jacob, and it was my duty to lead the group of players to the tables that formed the stage. In this way, I created a path between the packed audience while singing “Clear out of this house!!! from all four sides, here we come, the father Jacob with his 12 people”.

In my hand I held the stick of an old broom to which a dried udder of an animal was tied and blown up with air. I waved this balloon each time over another head, and thanks to my calls and waving the balloon on their heads, I cleared a path to the stage, for the “Father Jacob” and his 12 sons; and all the people of the town took pleasure from the young talent. For many years, this play was a topic of conversation in the town, and they even predicted a bright future for us – and their hearts were filled with pride for their town.

The Bobowa Chassidim

The Chassidim of Bobowa assembled at the premises of Reb Chaim'l Din. About 99% of them were young boys, and they were even more bound by their restrictive observances than others. Most of the Chassidic youth in the town, congregated specifically with them, and they spent most of the hours of the day studying Gemara[3] and annotations to the Talmud, in a very concentrated way; for they knew how to extract the depth of meaning from their studies in Chassidic conversations about the Chassidic way of life and their teachings. These discussions ended mostly with a sing-along by them all, and characteristically, everything was created by them – in other words, these songs were composed in Bobowa, at the table of the Rabbi, when the Chassidim gathered in their hundreds on the festivals and on other specific occasions - on the Sabbaths such as, the Sabbath of Channukah, Shabbat Shirah[4] and Shabbat Breishit.[5] Most of the chorus and melodies were created at these gatherings and were therefore much loved and accepted by them. These melodies were interwoven with divine devotion and became part of their daily life.

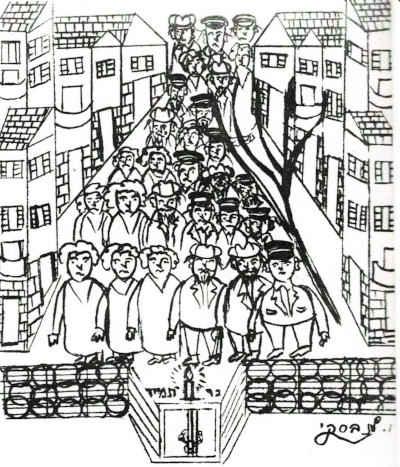

[Page 11]

They also defined and adapted Bobowa Chassidism for themselves, as a way of life, a mode of conduct in public, and particularly in the home and at the marketplace. And in this way their Chassidism encompassed them, it was their whole world. In the town, their devotion was expressed at the end of the Sabbath, at the time of the “Melaveh Malka”[6] meal, with songs and dancing. They continued in this manner for many hours. Their way of life was even more evident on the festivals, when all those who prayed in the prayer house of Reb Chaim'l, gathered together, as well as the parents of sons who were Bobowa Chassidim, and those who came from the “Trzcianka” neighborhood to hear Mendele Shiff, a Chassidic young singer. On the evenings when he sang “Ma ashiv ladonai”, from the “Hallel” prayers, and the “yah ribbon olam v'olmaya” from the Sabbath psalms, and other sections from the prayers and melodies of the Bobowa, the rejoicing increased. His singing attracted many of the townsfolk, particularly on the festival of “Simchat Torah”, when Reb Chaim'l went to arrange the ritual of the “encircling” of the prayer house, in the town's synagogue, that was called in Yiddish “the “urban synagogue”. Then, he was accompanied from his prayer house by his congregants and all the Bobowa chassidim and they turned this process of escorting Reb Chaim'l into a procession of singing, hand-clapping and Chassidic dancing, all along the way, for about half a kilometer. At the head of the procession were two small boys, one carrying a bottle of kerosene, and the second carrying a large Havdalah candle[7] above a flaming torch, that even the wind was unable to extinguish. That was because each time the candle sipped drops of kerosene from the neck of the bottle, it squirted all the kerosene strongly above the flame of the candle and created bubbles of fire in the air that rose, and went back and forth above the flame, and so forth. The curiosity and the excitement that arose from the actions of the two small boys, drew a huge crowd behind them, and by the light of these flames, they continued until they reached the urban synagogue. And there the procession ended with “ecstatic” Chassidic dancing around the lectern. This story reminds me of a friendly conversation that I had with the son of Borgenicht, when we were convinced by him, to watch a procession like this, and then the son named the song, the hand-clapping and the dancing, with these words “this is the uncivilized Asia”. Now, after 50 years, when we see the dances of the rock-n-rollers and the pop groups with their pop music, and the strange expressions on their faces - all this attests, not only to an uncivilized Asia, but to the jungle and the wilderness, that unfortunately continue to overtake us.

A Dispute Between Reb Chaim'l Din and Reb Moshe Lipschitz

It was already clear then, and undeniable that this was a holy war for its own sake. This was a wrangling between two groups, each one with its own representative, arguing about who should occupy the chair of the rabbinate in the small town, and who should not.

Many years after the death of the Rabbi of the town, Reb Tuvyele, life in the town continued without a Rabbi, and Rabbinical jurisdiction was left in the hands of Reb Menashe Din and Reb Chaiml'e Din. In truth, there was not much love between them, but their differences never led to open confrontation. Each had his own way of thinking and his own views. Reb Menashe Din was a great Jewish scholar with a depth of intelligence and full of the wisdom of life, but he was cold as ice, introverted, and did not attract Chassidim around him. He was a sort of “dissident”, but he was not this either. He wore normal clothes, as all the other “leaders of the community” (as they were called in the town), and he also did not sit at the eastern wall in the Chassidic synagogue where he prayed; nevertheless, he had a few admirers and close associates. In contrast, Reb Chaiml'e Din was an heir, in a certain sense, as he took over the house and the synagogue of Reb Tuvyele, of blessed memory, the last Rabbi before the First World war. This position had already created a greater sense of privilege for him; so, a group of his followers created continuity of the work of Reb Tuvyele in this synagogue. He even saw himself as heir to the throne after his predecessor and his appearance was that of a Chassidic figure. His attire was also “Rabbinic”, with a wide-brimmed, velvet hat

[Page 12]

and a Chassidic kaftan. In all his ways, he stressed that he was of Rabbinic descent, for this is what he wanted to be, but unfortunately for him, Reb Naftali Teitelbaum, the father of Menashe and Binyamin Teitelbaum, lived in this period. (I purposely recall the names of these two sons because this is the only opportunity to amend the error that Alfassi, the author of the Book of Chassidism, made in his book, where he stated that Menashe Teitelbaum was the last in the chain of the Teitelbaum Rabbis). We, the people of the town in that period, know that only Reb Naftali carried the cloak of the Rabbinate. His leadership declined at the Chassidic table in the “Chassidic Shtibl” [prayer house], together with that of the scribe Reb Yak'l Dovid, may he rest in peace, the acclaimed writer of religious texts, as well as the main educator in the town. Reb Yak'l Dovid left for the town of Tarnow, and Reb Naftali continued to gather the Chassidic group in the Chassidic prayer house. This group functioned according to the town's traditions and was dominant in the Jewish community and the town council. With Rabbi Naftali's departure, a vacancy was created within this group because Menashe Teitelbaum himself, did not have the ability to fill his father's place. He was one of the wealthy among the ordinary Chassidim in the town, and nothing more; and even less than him, in every way, was his brother Binyamin who did not even know how to study a chapter of the Mishnah. However, this did not stand in the way of him being the agitator, the definite article, of every intrigue and every unpleasant scheme in the town. After the death of their father Reb Naftali, they, and their group created a spirit of hatred that had been gathering in them from the days of the Rabbi, Reb Tuvyele, and this time they turned against Reb Chaiml'e Din who remained as heir to the house of Reb Tuvyele. They began to slander against Reb Chaiml'e, saying that he was seemingly unworthy of taking the position as Rabbi of the town, and in this way, they poisoned the atmosphere, to the point of terror. They brought the grandson of Reb Tuvyele, to add to the pressure against Reb Chaiml'e - Reb Moshe Lipschitz, you will never believe! Don't ask what turmoil and controversy were brought upon the town. Happy is the man that did not hear the extent of the vilification from the two sides, and well done to all those who did not participate in these intrigues.

The Elections for the Rabbi

Truly, the followers of the Teitelbaums, did not feel that they had the upper hand, because there were three camps who had more influence than them – firstly, the camp of Reb Chaiml'e Din – but these were not regarded as the wealthy of the town, or those of repute in the town. What would one say about the wealthy – that there was not one among them who was prepared to take up a position of honor, to be the leader on the committee of the congregation, or a member of the town council etc. and this would work against them more than anything else. The second camp was the Wielopolel Chassidim – since their Rabbi was not a candidate for the elections, the whole issue of the elections did not create much enthusiasm among them. The whole matter of the elections in general was of little interest to them. So, the small camp of Menashe Din was not as concerned about the Rabbi as they were about the Teitelbaum group, as they would no longer allow themselves to be burdened by the Teitelbaum group's control over them. A large portion of the ordinary people were against this group - yet among them all, not even one person stood out, who was communally active, who would be able to unite them towards a specific goal. The Zionists consisted of an organized strike force but in those days, they were mostly young, and their attitude to the elections was completely passive. Opposed to all of these, stood the controlling group that consisted of all those who were considered wealthy members of the town. Even all the “who's who” who wanted to raise their image in the eyes of the residents of the town, and all those who sought esteem and affluence, were taken into their framework and for these, all that they desired was “shlita”[8] – that they would live long and happily. Amen.

[Page 13]

Two Yechiels

These two Yechiels clarify for us and demonstrate everything that occurred in the town at that time. A defining example of this was Yechiel Asher. He was a very poor Jew, so much so that he was not even able to pay rent, and a room was organized for him in “Hakodesh” (a building that belonged to the community that was used to accommodate overnight stays for beggars and visitors passing through). He, his father-in-law and all his relatives, prayed in the prayer house of Reb Chaimle Din for many years, because they all lived in the “Trzcianka”, the neighborhood of Reb Chaimle Din. When the frenzy of the elections for the selection of a Rabbi arose in the town, this Yechiel Asher was the loudest and most active propagandist in the camp of Reb Chaimle Din. After two weeks he changed his mind and became “the” propagandist for the opposing camp. Suddenly, after a few days, Yechiel Asher, as well as his sons, wore new clothes, and in addition, began to trade in fabric, at the market. I remember a very sad incident when my father, may the Lord avenge his blood, accompanied me to the well alongside Reb Wolf Laub prayer house and we chanced upon Yechiel Asher. My father asked him, how come, he so suddenly changed his position? With that, this Yechiel Asher, who was more adept at explaining with his hands than his mouth, slapped my father Betzalel, of blessed memory, in his face. As I write these lines, the sound of these slaps, ring in my ears - the echo of what can happen in a war of Jews against Jews.

The second Yechiel was known to us as Yechiel Sumres. And if we refer to the first Yechiel as refined, although he was rude and impolite, then we would not be out of line if we called the second Yechiel, offensively vulgar and insolent - there was no one like him. No one in the town could imagine that he would dare to do such a thing to an old man like the Wielopolel Rabbi. This is what occurred. This Rabbi was in the habit of descending the steps to immerse himself in the Mikveh[9], wrapped in a sheet and accompanied by his shamash[10]. As he descended the circular stairs, this Yechiel was covertly waiting and extended his foot, caused the Wielopolel Rabbi to fall and suffer severe injuries. It was only a miracle that he did not break any bones. The people who witnessed this scene, grabbed Yechiel Sumres and beat him severely. Thanks to the intervention of the injured Rabbi who screamed out: Jews, you are beating a Jew! Let him be! So, he was rescued from the hands of those who were beating him. These beatings caused him to be confined to bed for a few weeks. All this could only have happened in an atmosphere of a reeking swamp, of venomous blind hatred that the group of tyrants created in the community. This continued for tens of years without ceasing, and all over a war about the seat of leadership.

How Reb Moshe Lipschitz Received the Appointment as Rabbi of the Town

Indeed, the issue of Rabbi of the town was not decided by the elections, but by the dominating group in the village who knew how to overcome all the obstacles and difficulties. They even acquired the assistance of the Gentile governors of the town, for example, the mayor of the town Dr Brzeski, who was the leader of the anti-Semites in the town. When his name was mentioned among the Jewish residents of the town, they would add in a whispering tone between themselves, “the mayor of the pogrom - ‘pogromtchik’. This matter reminds us of the sinful behavior, that in my humble opinion, the Jews were in the habit of whispering the words of the “rebuke”[11] on the Sabbath in the synagogue, as if, in this way, they would sweeten the bitter pill of truth and create for themselves the illusion, that despite all, it was not so bad, and did not directly affect them. As stated, the Rabbi's group collaborated with this Dr Brzeski for many years. He was interested in ruling the Jewish community, and for this purpose, he took the

[Page 14]

village elder as an assistant, and even had the support of the governor of the province in Krakow. All these factors worked in favor of this “group”, so Reb Moshe Lipschitz was installed as Rabbi of the town. After his appointment, the community commenced building a house for the Rabbi. The house was built on part of a plot of land that had been designated for the building of a Talmud Torah[12]. They did not build the Talmud Torah, rather a house for the Rabbi at the expense of the Talmud Torah. So, the following incident exemplifies the manner in which “this group” gained power and retained it. The incident concerned Advocate Deiches, the only Jew in the town who publicly desecrated the Sabbath; precisely he, was chosen as head of the community by the “important, established members, and the Chassidim”, led by the town's Rabbi. I remember a strange incident that I saw, and heard with my own ears, and became common knowledge in the town, following the debate between Advocate Deiches and Advocate Horowitz. The former was the representative of the Chassidim and the Rabbi, and the latter, a candidate representing the people, and an opponent of the group of Chassidim around the Rabbi, who were the spokespersons and representatives of the town all the years. This was the story. Advocate Deiches came to deliver an electoral speech in the “small Chassidic prayer house” to the Chassidic community prior to the Jewish community elections in the town. So, the strongest young Chassidic men stood guard at the front gate, but the Zionists and the ordinary people overpowered them, forced their way inside, and became the guards at the gate. They allowed everyone to enter, but no one to leave. In this way they forced the Chassidim to allow Advocate Horowitz to speak. The following is an extract from the words of Advocate Horowitz in this public debate:

“Are you not ashamed, you who pretend to be “anshei Shulchan Aruch”[13] and regard yourselves as “shlomei emunei Yisrael”?[14] You are in fact, supporters of the only man in the town who publicly desecrates the Sabbath. If this means that this Jew is fit to be your representative as head of the community, then I am prepared to promise you that from today onwards, I will also travel through all the streets of the town on the Sabbath. In addition, my wife will also cease buying kosher meat in a Jewish butchery and will cease lighting candles on the sabbath, and I myself promise further, that I will not eat less pork than your strictly kosher representative: Nu! Where are you, Rabbi of the town? On the basis of these promises of mine, will you regard me too, to be fit to be representative of the Jews of the town, within the community?”!

I have highlighted this phenomenon that is characteristic of the town and demonstrates what is unique to it.

The Chassidim of the Town's Rabbi

I find it very difficult to define these Chassidim, because the question that arises for me is, can they in reality, be called Chassidim of the Rabbi, because Chassidism is a way of life, it is a shared past, that is also tied to the “courtyard” of the Rabbi – in other words, a charismatic personality from a prestigious dynasty, whose good name precedes him, and charms the community so that they would follow him, either in his own right, or by the prestige of his ancestors. These are my impressions as I understand it, and according to events that I experienced until 1932 - after that I spent more time on Hachsharah[15], than I did in the town. In my humble opinion, what follows was the manner of conduct of the Chassidim of the local Rabbi in Briegel. Theirs was an attempt, to create at all costs, Chassidic adherents of the Rabbi, so that he would become ‘the' Rabbi of the town; however, a Rabbi with a Chassidic court, did not exist. Since the group of established members of the community considered themselves superior to all, and for decades were accustomed to having all their demands met, they were only interested in this type of Chassidism, in the artificial way that it was created. We will take as an example the Chassidic “shtibl”[16] – can they be considered Chassidim of the Rabbi? There never existed among them, Chassidim of “Żabno”, “Bełz”, Chassidim of Muzshitz or Chassidim of Gur; on the contrary, they were not defined units,

[Page 15]

and their existence was therefore not felt as separate units. In addition, regarding matters affecting the life of the community in the town, they swam with the ruling current in the town and gathered around the Rabbi of the town. Among them were those who were completely removed from Chassidism but were drawn into the group for all kinds of reasons. Some were sycophants, and some were careerists who knew that this group determines the social status of members of the community, but there was nothing about them that could be regarded as the spiritual life of Chassidism. The Chassidim had less influence among the youth, and this angered the Chassidim, and they did not feel comfortable; but what angered them most, was the concentration of Bobowa Chassidim, who found their place with Reb Chaiml'e Din. The Bobowa Chassidim introduced something new into the town. They brought young people from the villages of Galicia to the town, and divided them among each of the established members of the community because they were able to assist the youth economically, by providing them with food, once a week; and this is how these young boys became “day eaters”- “eating days”[17] in Yiddish; but the followers of the Rabbi did not want to accept this seemingly positive idea (a regrettable stance), according to the generally accepted thoughts at that time. As these were Bobowa Chassidim who lived in the poorest circumstances in the town, the followers of the Rabbi therefore schemed “let's outsmart them”. They began to bring youth from the vicinity to evict the Chassidim of Bobowa; they demanded and influenced others to cease providing “eating days” to the “Bobowa” youth, but, to the good fortune of these young boys, the majority did not comply with this cruel demand. However, the followers of the Rabbi reduced their “eating days”, for some, by one day, and for some, by two days, and even three days in the week. As a result, the youth on both sides were starved, but what possessed those who wanted to rule the town, by whatever ways and means, to allow this.

Typical Events in the Town

These issues happened in our presence, and there is a connection between them and between the group that dominated the town because the monopoly over public life was, from now on, in their hands. It was therefore sufficient, if one of the Chassidim of the Rabbi in the community, who believed that an employee was earning an unimaginable sum of money, to covet that job of work. He immediately began to agitate among the public, that the employer was dissatisfied and needed to replace the employee. So, they began to harass the “ritual bath attendant” of the “public bath house”, “Reb Shmuel Ballan”, who had done this work for many years. He was a conscientious Jew with an exceptional work ethic. Except for Friday, he worked every weekday, loading and unloading coal at the train station for the “Shteinlufs”[18] and this was his main source of income, and his position as attendant at the bath house was secondary for him. He earned a decent living from these two occupations, but among the followers of the Rabbi was Chaim'l Loyes, who coveted the position because he was unsuccessful in his business; so, in their opinion, he deserved to be the bath house attendant, and they did not allow “Shmuel Ballan” his rights, after 20 years of employment, because the followers of the Rabbi knew how to create an atmosphere of animosity towards him. One had to be as hard as steel to endure this. And then, as usual, two camps arose – one for, and one against “Shmuel Ballan”. The whole town engaged in a whirl of arguments that was a daily occurrence for the followers of the Rabbi. The conflict lasted many months, stirred them up, and became a source of spice in their lives. “Shmuel Ballan” was forced to vacate his position as bath attendant and Chaim'l Loyes replaced himj, but quick as a flash, it became clear that he was a complete failure, and then his two brothers-in-law came to his aid. But his failure was so great, that the joy of his misfortune was shared by all the members of the community, and even before their joy dissipated in the dwelling places of the town, a very serious problem suddenly arose from a very joyous event that was, the episode of Nissan “Dov”.

[Page 16]

Nissan “Dov”[19]

Nissan “Dov”, that is what he was called in the town, because when he walked, he brought both his knees forward, resembling the gait of a heavy, awkward, bear. This Nissan “Dov” was the brother-in-law of Chaim'l Loyes, in other words, his in-law, who eked out a meagre living (there were only a few people in the town who made a good living). Then the time of baking matzah approached, an activity was under the authority of the communal committee because this was a profitable industry from all points of view. Then Nissan “Dov” was appointed to the “responsible” task of mashgiach[20] for baking matzah. He checked the girls and women who kneaded the dough or used the wooden rolling pins to roll the matzah, so that God forbid, he should not detect a morsel of dough beneath their fingernails that could possibly make it unfit for Pesach. The time of baking matzah was an important event for the people of the town and many of them used to visit the bakery to witness the Matzah baking, at least once, so that they could absorb the experience of matzah baking. So, Avremele Bom, the clown in the town, and his friends, arrived there and when he wanted to cross over the threshold of the bakery whose doors were always open, Nissan “Dov” stopped him, and none of Avremele's arguments helped him to gain entry. His excuse was that he only wanted to speak to his bride. Nissan “Dov” stated firmly that without a head-covering, he would not be admitted, come what may! Avremele conceded! But not without the revenge that Nissan “Dov” deserved. He went home to get a kippah. In the meantime, Nissan “Dov” was informed that Avremele has no bride, and in any case, she does not work at the bakery. Avremele took a large domed velvet hat from the house of his neighbor, Shmilchel Melamed, filled the hat with soot from the chimney of the stove and returned directly to the matzah bakery. By now Nissan “Dov”” was well-informed about this Avremele, so when he came to the entrance of the matzah bakery, Nissan “Dov” approached him, swearing: you devil, do not dare enter here! Devil! Be gone from here, devil, and repeated this screaming, but Avremele was undeterred and pushed his way inside. Nissan “Dov” grabbed the lapels of Avremele's coat and continued screaming; and the two of them were wrestling and struggling, accompanied by their shouting … then Avremele took off the domed velvet hat filled with soot and squashed it into Nissan “Dov's” face. From the midst of the shouting of these two, all the staff working in the bakery, burst out into hysterical laughter when they saw Nissan “Dov's” sooty face. The tumult of the laughter and the shouting brought a rush of Chassidic students who were studying in their “small prayer house” on the top floor above the bakery; so too, the neighbours in the vicinity arrived, all of whose faces wore expressions of rejoicing. With the intervention of all the spectators, the wrestlers were separated and Avremele's friends persuaded him to demand a Rabbinical judgement and the whole town was overjoyed about this event.

A short time later, after the Ma'ariv prayers, curious people began to gather at the house of the Rabbi, encouraged on both sides by the incident involving Avremele Bom. And soon Nissan “Dov” arrived with clearly recognizable signs of soot in his eyes and around his nostrils. And immediately everyone burst out into unruly laughter, and Avremele Bom, who had been waiting with his group for Nissan “Dov”, entered after him, and the two camps separated – each group on its own side, at the Rabbi's table, each one waving their hands in the air. While they were calling out derogatory terms and causing a commotion, suddenly, the door to the Rabbi's private room opened, and the voice of the beadle echoed, ‘the honored Rabbi'! The honored Rabbi! And a silence immediately reigned in the room of the Rabbi. He was broad-shouldered, not too awkward, only with a large pot-belly. He sat down at the head of the table, exhaled heavily, and turned directly to Nissan “Dov”. What is your allegation? And what do you have to say? And Nissan “Dov” revealed in detail what happened with Avremele at the bakery, He pointed to his face and said, that for two hours, he had stood and washed his face with soap, but was unable to remove the soot from his eyelashes and his nostrils.

And everyone burst into laughter, and then immediately became silent because the

[Page 17]

Rabbi turned to Avremele and said: and what do you have to say Avremele? And Avremele prepared himself and contended: (a) It is true Rabbi, that he did not let me enter the bakery because I did not have a kippah on my head, so I went and asked for a kippah from my neighbor Reb Shmilchel Melamed. How was I supposed to know that Reb Shmilchel keeps his kippah in the chimney of his stove, and that it was full of soot; and it is clear, how in a brawl like this, Nissan “Dov” dirtied his face. Look what he did to me: he pointed to the two torn lapels of his coat, emphasizing and repeating: behold honored Rabbi, in the struggle, he tore my coat, and he was dirtied by my kippah, and I am seeking damages from him, for my coat. And Avremele raised his voice more emphatically as he turned to the Rabbi. Rabbi why does Nissan “Dov” not mention anything about the fact that he threw my fringed undergarment from the mountain slope close to the bakery. After these words, no one in attendance was able to contain their laughter. The Rabbi remained astonished and dumbfounded at the unruly laughter from all of them. Then there was a whispering among the people of the Rabbi, and one of his associates took the courage, bent down, and whispered in the Rabbi's ear that this Avremele has no children because he is not married yet… and like a bitten snake, the Rabbi burst out at Avremele: Prankster, get out of here, and he turned to his Chassidim, with these words: distance yourselves from this serious Jewish criminal. Everyone withdrew and removed themselves from Avremele, and in doing so they created a path for Avremele and his friends to leave the Rabbi's house. This departure was accompanied by derogatory chants towards the Jewish criminals. This incident caused by Avremele, made the Rabbi and all the people of the town, ridicule and denigrate Avremele. The whole town laughed spontaneously at itself, for many days, but this was a healthy laughter that made them feel good.

Reb Shalom Din

Although this incident happened approximately two or three years after I had already been living in Israel, that is, in 1936, I find it necessary to add to the story about Shalom Din, seeing that he was a target of the deviousness of the town's Rabbi and his followers. I allow myself to quote from the book of Isaiah, chapter 3, verse 4: I will give children to be their princes and babes shall rule over them.[21]

After some years of ruling without restraint, the reign of the Rabbi and his followers was weakened, because they had not come to terms with the changes that had begun in the town. From time to time, they stirred up the emotions of the people of the town, with a new problem – this time about “Shalom Din”. He was the eldest son of Reb Menashe Din from his second wife, whom we knew. Reb Menashe Din was now very old, felt that his strength was failing and all he wanted in his final days was, that his son Shalom should replace him as a Rabbinical judge in the town; but to his wish there was already a question mark – whether they would accede to this request. The fact that Shalom and his brother Moshe had studied for many years in the prayer house of Reb Chaim'l Din, that is, with the influence of the Bobowa Chassidim, was certainly sufficient for the Rabbi and his followers to oppose Shalom's appointment as a judge. But this time they did not dare to appoint another candidate to stand against him, because they felt that their control over the town was waning. This, however, did not prevent them from restricting his appointment, because the Rabbi, by virtue of his official authority, had to give his approval. But this time, his response was of a more restrained nature. Indeed, the two sons of Yechiel who beat Moshe Kapler, the younger brother of Shalom, so aggressively because he used the term “the fat Moshe”[22] to describe the Rabbi. This is what the fierce opponents of the Rabbi called him, as they lacked the ability to hold their tongues. But the youth among the ordinary people, knew immediately, how to counter their opponents, twofold, and they were more adept at this, than all the strong men of the Rabbi. These youth, cast a fear among the Jewish community, but they maintained an incomparable order, unlike in previous years. Reb Menashele Din passed away and left a will in the hands of one of his admirers. And in his handwriting, he wrote: he should not be buried

[Page 18]

until the Rabbi grants approval for his son Shalom to replace him as a Rabbinical judge. Only a few of his close associates knew about this request. In the morning, it became common knowledge that Reb Menashele had passed away and there was a to-do among all the people in the town, all wanting to attend the funeral. A few gentiles also participated because he was regarded among them, as the “wise” man of the town. It is worthwhile mentioning that Baron Goetz who owned the largest “beer” brewery in Poland, in the town of Okatchim, adjacent to our town of Briegel, would consult with Reb Menashele from time to time, on judicial matters. As a gesture of thanks for his advice, the Baron would send a wagon load of coal and potatoes every year to Reb Menashele, for the winter. The Gentile Ravitzki, the wealthiest man in the town and a great admirer of Menashele Din, used to take advice from him, on all legal issues and would accept all his rulings without appeal. When he was asked how he can accept every judgement without appeal, he would answer in his broken Yiddish: “if Reb Menashele provides this judgement, so must it be”.

When the bier arrived with the corpse at the open grave, the trustee of Reb Menashele's will, read it in the presence of everyone who attended, and this is what was written: you will not bury me, until you appoint my son Shalom, as a rabbinical judge in the town, in my place. In this situation, the Rabbi and his entourage were lost for words. At the open grave, the Rabbi was forced to announce: indeed, I will appoint his son Shalom as a judge in the town, in his place. Then the corpse was lowered into the grave, and they continued with the eulogies. When the grave was covered, the people of the town returned home, with feelings of great satisfaction, certain that they had finally got rid of the dilemma regarding Shalom Din. But the entourage of the Rabbi were not of the same opinion. The days of “shiv'ah”[23] passed, and they did not come and comfort the family of Reb Menashele, and therefore did not bring the official confirmation of the appointment of his son, Shalom. Even more so, they seethed with anger, and their antagonism became so much stronger and more forceful in the town, that those who prayed in the “small prayer house” the stronghold of the Rabbi, prepared themselves for a protest and a crushing defeat. On the Sabbath, when the Rabbi came to morning prayers, Shalom, the son of Reb Menashele followed right behind him accompanied by worshippers, led by Yechiel Pepper, a man with a limp, who declared in a loud voice: “welcome Reb Shalom Din!”, and many people rose and applauded in his honor. This protest became the last straw that broke the camel's back. The following day, after the Sabbath, the news spread that on the day after, the Rabbi would appoint Shalom Din. Indeed, he was congratulated, and the town was at peace for some time. In addition, among the three main streams of Chassidism that existed and whose presence was noticeable in the town, were: the Wielopolel, the Bobowa and the Chassidim of the town's Rabbi. Among themselves, they never found a common language, and the hatred drove them crazy. Although there was no difference in their principles that should divide them, the only issue was, belonging to one camp or another. From time to time, their actions became so heated that it reached a level of blasphemy. Problems and gossip were invented daily, in order to justify and continue confrontation.

The Zionists in the Town

In my perception, in a general review of a period of 10 years, i.e., from 1923 – 1933, I will allow myself at the outset, to describe in a limited way, the mood of that period and its influence on the residents of the town. Indeed, this was a period of the greatest development of the spirit of enlightenment among the Jews, in which a strong yearning for general culture arose. A great many Polish inhabitants were carried away with this new current, but Briegel remained fossilized around Chassidism. Although the town was blessed with a rare flower, in the image of Mordechai Dovid Brandstatter, a writer of the enlightenment period, who produced works together with Peretz Smilansky, however, that was 60 years earlier and no trace of it remained in the town. Not one honorable person arose who was able to withstand the Galician Chassidism. There was, therefore, no one to organize the scouts and to encourage them to support the Zionist idea. Although the flame of the spirit of Zionism was aroused with the granting of the “Balfour Declaration”, at that time, the most perceptible factor

[Page 19]

were the pogroms that passed through Galicia and in Briegel itself; but there was also a lack of cultural, spiritual, and social personalities who could lead the wider public in the path of Zionism. As a result, everything remained as it was, as before. Nevertheless, there was a crack, created by the youth in the wall of the Chassidic fortress of the town – by a small part, who dared to be involved in a Zionist youth movement that focused on collecting funds for the Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael,[24] as well as creating a secular library, and even a dramatic group. From these youth, the “Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir”[25] youth movement was born.

Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir

It is with great sadness that I write these lines with a heavy heart, because no member of “Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir” in the town, could be found who was prepared to write a particular article about events that occurred in the organization in that period. I do not pretend, God forbid, to fill this gap because I am not the one who is able to evaluate adequately, the extent of the activities of Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir. Yet, as a writer, and observer of events in the town, I am not able to describe the agenda without mentioning this youth organization, that was the most important organization of its kind. It was the forerunner that brought a spirit of rebellion into the town, against accepted conventions, and became a serious and crucial element in the lives of the youth in the town. In 1924-5 when many of the Chassidic youth and the bourgeois joined the ranks of Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir, and an all-out war began between all the Chassidic groups, against the Zionists in general, and against this youth organization in particular; but the problem for the Chassidim was, that their war soon proved to strengthen the power of Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir. Even though those who accused the youth of vile plots, and matters that reached the courts of law ended with a compromise and a truce, Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir reached its peak in those days. Who in the town did not know Ruven Leichter of blessed memory, and which young boy or girl did not speak of Yossel Tandy, known to us as Yosef Honig who lives with us in the Land of Israel? Its development continued until 1928. The finest youth congregated around Yossel Tandy, but he was selective in choosing specific candidates among the wider, general youth in the town. Those who were affiliated to him, saw themselves as “bessere kinder”[26]. Indeed, he adopted for himself a Chassidic uniqueness, even externally, in his attire and his manner. One must add that he knew how to create an exemplary pioneering image, because he knew how to consistently emphasize the idea of self-fulfillment, that was expressed in Palestinian centrism, and the kibbutz, as it was in those days.

He formed a significant Zionist youth organization and used it as a Zionist hothouse in the town, and all the other activities and events were drawn from this source. In 1926-7, after “Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir” followed in the footsteps of the German organization, the “Vander Fogel”[27], the spirit of socialism and its culture influenced him more and more, and even cosmopolitanism seeped in. This was actually expressed by learning the language “Esperanto”[28]. With time, his philosophy turned sharply left, and little by little, he began to distance himself from Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir. In 1929, when the rift with him began, and the organization began to crumble, its decline was felt in the town. In 1930, after a year, Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir came to an end, and only a few individuals remained faithful to its ideals.

These words were written before Rachel Hammer saw fit to write about “Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir”. May she be blessed.

[Page 20]

A General Awakening of the Youth

As I have already indicated, in those days there was an awakening among the youth groups that manifested outside of the prayer houses. These were young people who searched for an outlet for themselves, and as they did not find their place in Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir either, they organized a sporting organization “Yarden”, but it lasted only for a short time, and was replaced by “Maccabi”. In those days everything was concentrated on soccer and most of the youth joined “Maccabi”. Over the years, in addition to soccer, this “Maccabi” developed other branches of sport, like table tennis, volleyball, bicycle racing, and it also became an integral part of the sporting life of the town. The Jewish youth of all kinds and groups in the town, belonged to the organization, except of course, the Chassidim.

I allow myself to add that the sporting groups brought much vibrancy into the town, however, I hope that someone will be found who will write the details about everything that happened among the sporting groups in the town.

The Drama Circle in the Town

The drama group was founded together with the establishment of the first youth organization in the town. This was a form of expression by the youth, who were in pursuit of the world of culture of that period, and they immersed themselves in reading classical Jewish literature or famed translations of authors of the nations of the world. These young boys and girls saw themselves as disseminators of enlightenment, and in line with this view, their first objective was to establish a library. Their second aim was to establish the drama group, for in this way it was possible to bring to life on stage, the characters in the story; this would also help to bring the stories to a wider audience. So, they were drawn into the trend that was prevalent among the Jews in theatrical troupes that were seen in Tarnow and Krakow. A group like this, attracted all those who regarded themselves as intelligent and knowledgeable, and were prepared to accept a role. In this way, they found social activities for themselves that even became competitive in a positive way. But one cannot hide, that even among these, there were significant attempts to dominate, and there was no lack of internal disagreement. But the desire to appear on stage, each one individually, and all together, was stronger than the disputes and the anger, and they succeeded in staging light performances. As was common among groups like this, there was a decline – some married or left the town, but in the course of time, other young people grew up and filled the gaps. In 1929- 30, when the youth matured, they surpassed the first participants in every way, but the difficulties and the problems did not change. The difficulty was, in finding a hall that would hold a few hundred people, because the youth matured, and the audiences to the plays increased. The hall that had been suitable, and designated for performances, the “Sokol”, was now taboo, closed to Jewish performances altogether, because these “Sokolists” who owned the hall, were the most antisemitic people in the town. They were led by Doctor Brzeski who was the mayor of the town for many, many years. There was another hall of a suitable size that belonged to the municipality, but it was not suitable for performances, and they did not want to rent this venue either, because they were influenced by representatives of the Jews in the town, all of whom were “followers of the Rabbi”. As stated, the youth matured, and some enterprising individuals arose, who knew how to create connections with a few of the Polish intelligentsia in the town, and with their help, the hall of the municipality was acquired – “the City Hall”. That year I returned from Tarnow to the town, disappointed and depressed. Even in the town, I was mostly unemployed, and looked for activities to pass my free time. And behold, a whisper spread through the town about the preparation for a play

[Page 21]

by the drama circle, that was the “The Golem”[29] by Levik. And why that? Because a group of intelligent people from among the adults travelled to Tarnow to see the play about the Golem by the “Vilna Troupe”, and they decided to stage that play in the town. So, the roles were allocated and those who had seen the play in Tarnow were preferred, because they had an advantage over those who had not seen it. There were objections to the allocated roles but somehow this was overcome. The actors invested their time in learning their parts and after two and a half months, word was received that the play would be performed two weeks later, this time, in the City Hall. The acquisition of this venue was of great importance because all the previous performances in the town were mostly presented by external troupes and took place in the large tavern of the “Tall Shmil”, or in the premises of the local fire department that was like a barn. So, we were notified that on the coming Monday, we would already begin setting up a stage, to enable the actors to become accustomed to performing and perfecting their roles on the stage. On that Monday, I was ready and alert, and waited until the group arrived and went upstairs to the hall. I remained in my place, for I was not part of the cast. Immediately afterwards, Leibush the wagon-driver, who lived on the way to the train station, appeared with a wagon laden with planks and empty beer barrels, that were known to the townsfolk as “a fertelle beer”, and he began the process of unloading the items. At that moment, I felt that this was an opportunity to earn the right to gain entry to a play rehearsal, so I approached the wagon, took some of the planks and went up with them to the hall on the second floor, as if I had been assigned to the task. As I was going up the stairs, I met the group coming down, on their way to collect the items and take them up to the hall. They turned to me saying: do you want to help? Very good! While we were taking the last barrels up, Shiye the carpenter arrived with his son Mendel as his assistant. They were carrying their carpentry tools and they went straight to work. I decided to participate in setting up the stage, and very soon became an assistant to the carpenter. At 6.30 in the evening, the floor of the stage was complete. Then they brought buns and herring from Yoshia Shnur, so that those present could eat to their heart's content, but many of them did not want to eat, so Shiye the carpenter, his son, and I, consumed the buns and the herring.

I had not eaten any food since early that morning, and the next day, I arrived as if I belonged to the place, and at 9 in the evening, the stage was complete, as well as the sheets of cloth around them. Only the curtain, and the paper required for the décor, had to be installed, and at this late hour, they began to rehearse the first act. Only now, when all the actors were arranged in position, they felt that something was missing: the “Golem”; so, they stood and thought and looked around, and then the director Ya'acov Faust of blessed memory, turned to me with a question – would I agree to be the Golem this time, just until they worked out a plan. And as I longed just to remain at the rehearsals, I agreed on the spot, to lie on the stage as a “Golem”; but what I was required to do, was to lie down, without moving one organ of the 248[30] organs in my body, and not to breathe, and it seems to me, that to this day, I suffer from shortness of breath due to this experience, where I was not allowed to breathe during rehearsals. This was how I was given the right to participate in the play as the “Golem”.

The play was a success, and all the revenue was dedicated for the building of the community center “Bet Ha'Am”, known as “Dom Ludowy,” in Polish. Indeed, those who were knowledgeable, asserted that the play was a “Burlesque”, and no more, but most people were proud of the courageous effort in staging this play, and they praised and complimented all the actors – but most of all, it gave the people in the town something to talk about.

After this play, they tackled the play “The Dibbuk”, by Sh. Ansky. I was invited to join this production, thanks to the fact that they knew that I had something to offer, and that I did not refuse any task that was assigned to me, except errands. So, I used my initiative to prepare the sheets of papers that were required for drawing the sets, and I became professional at glueing paper, like the workers in the paper bag industry. And this time, truly, there were no mishaps and no paper tore while illustrating or when hanging the illustrations on the wall. In the first days, I was not allotted any tasks, only with time,

[Page 22]

I was assigned an insignificant task, of the lowest kind. Even the “role” of being one of the “Djaddes”[31]. Why “Djaddes” and not “Evyonim”[32] or “Kabtzanim”[33]? I will never know. The task of learning my lines was not an effort for me because I only had a total of six lines, and I learnt them during rehearsals. On the other hand, in designing the character of the pauper, I was faced with many comments from the director, following my interpretations of the beggar that I had been practicing. I experienced the communal life in the villages and towns, as distorted as they were, with the wealthy, and the officials in the community who exploited the poor, and I was repulsed by them, and held them in contempt. I, the pauper, needed to uphold my rights, but in contrast to my view, the director expected me to appear as a wretched beggar without any self-worth, seeking mercy, with garbled speech. Indeed, at rehearsals, I practiced being the character as directed but I did not conform on stage, on the night of the performance. That night I was true to myself and performed in the way that I had interpreted and practiced - being my grotesque character. As I made my entrance on to the stage in my role, I felt like one who was being forcefully pushed, but I overcame that, which was preventing me from entering. I breathed out heavily, sighed and groaned when I turned to the wealthy man, with gestures accompanied by such facial expressions, that the entire audience understood that this was to antagonize the “rich man”. Since all my words were a “monologue”, without a need for “response”, I allowed myself to add words that were not in the script. The director and the prompter were dumbfounded. They were seething and rushed to close the curtain and throw me off the stage. It was my good fortune, that when I said the second sentence, the audience burst into applause as they identified with my pauper's arrogance. Thanks to this, the director calmed down and allowed me to continue as I wanted. At the end of my appearance, I turned to the door, raised my hand and pointed with my finger, implying, wait! Your day will still come! And again, I was rewarded with an encore. I recall another unique detail – no matter how much I learned to conceal my image with my costume and perfect make-up, so that I would be completely disguised, I did not succeed in concealing my voice, and in their excitement two people from the audience called out “Chaiml Tzalles!, Chaiml Tzalles”!.

I would like to mention the three main actors “Leah”, who was the second daughter of Feibysowicz, “Chanan” who was “Pardek Shpielman” of blessed memory, that I loved, and the Rabbi from Miropoli, the son of Shprintze, who made and sold sour cabbage, sour apples, cucumbers, and the liquid of the cucumbers, and also bran borsht – sour bran.

It should be noted that everyone succeeded in their roles in the play because the characters that were portrayed, were well-known to us in our daily lives. For this reason, the play succeeded beyond our expectations. After all, this was a local amateur troupe that added a level of interest in the conversations among the townsfolk, and also added to the flavor of cultural life of the Jew in Briegel.

Akiva

In 1926, the youth organization, Akivah, was established in Briegel. This was the first branch of Akiva and was founded by three mature young women - the eldest daughter of Kleinberg, Shprintze Fishlberg, and the youngest daughter of Seelengut. They had come into contact with this organization in Krakow and Bochnia. This was a youth organization of “Gimnazistim”[34], national Zionists, but in those times, it did not stress Palestinian Centrism and the kibbutz movement at all. This organization was a more trendy one, than a pioneering one, and received only a few high school graduates in our town, those who were not involved in Ha'Shomer HaTza'ir. They participated in learning the Hebrew language and the activities of the Jewish National Fund, but they did not manage to formulate a strong nucleus, who would be able to sustain its existence, and after a year and a half, it was disbanded. At the beginning of 1930,

[Page 23]

three young men, who had belonged to Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir, initiated the establishment of a “Cultural Center for Youth”, without a name. They were our acquaintances, the son of Borgenicht, and Mendek Eisen, both of whom live in Israel, and Hershel Leibel, may the Lord avenge his blood. Within a short time, the “Hebrew Youth Association” grew from this cultural center. It struggled very hard to maintain its existence, for in that period of time, the youth ceased to belong to organizations at all; yet a few of the youth of the town, from simple families and from among the poor joined, and they specifically, persevered. It is natural, that this organization, in contrast to Ha'Shomer Ha'Tza'ir, opened its doors to all those in need, and in this way, young boys and girls from among the poor families in the town, joined. Over time, this youth organization changed and became known as “Akiva”, and no organization like it, preceded or succeeded it, neither in its organization nor in the number of its members. I will add, that when I came to the town on a visit from the Land of Israel on a Sabbath in 1938, the cultural center still existed but no one visited it.

The Left-Wing Po'alei Tzion[35]

In the years 1931-2, there was again an internal drive among the youth, and the left-wing of Po'alei Tzion was established, that managed to gather more than 40 members. The organization was led by Elisha Shternlicht of blessed memory, but after a few members that belonged clandestinely to the communists penetrated their ranks, this organization came to an end, but a few remained loyal to its program.

Ha'Shomer Ha'Tahor[36]

In that same year, for the first time, a religious youth movement was organized, called Ha'Shomer Ha'Tahor, under the leadership of Heshek Moses. He managed to enroll about 20 girls and one boy, but he did not succeed much, in maintaining an organized group in his premises.

The Artisan Organization

In that same year an attempt was made to create an organization for adult “artisans”. I do not know who, or what was the purpose for establishing such a group, but a room was hired as premises at the “Subyobeh”, where I visited. There, the artisans spent their leisure time playing dominoes and draughts. The leaders of the organization were Ostreich and Berklhammer. After about half a year, it came to an end. I do not know more about it.

Bnei Tzion[37]

It can be said that this organization, did not live up to its name. All that was known was, that its members comprised mature youth who had left various other youth movements - those that did not find their place in other youth movements. Secondly, they did not see themselves as fulfilling their Zionist ideals, actively; but they considered themselves Zionists by belonging to a Zionist movement, buying their “shekel”, donating to Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael,[38] and to Keren Ha'Yesod,[39] and supporting a Zionist movement. They represented a political party defined as Zionist and the numbers of this adult youth grew, yet they spent their time socializing. So, a need was felt for a building that would include the library and other institutions that were growing, particularly a hall for performing plays, information evenings, parties, etc. Over time, an important part of this adult youth became significant active members of the community, and they took the initiative in establishing a central building for the needs of the community. They took immediate action and

[Page 24]

harnessed all their passion, to achieve their aim of establishing “Bet Ha'Am”, “Dom Ludowy” in Polish.

Bet Ha'Am “Dom Ludowy”

To achieve their aim, they invested most of their time and energy around this one and only issue, the “Dom Ludowy”. At the end of one year of activity and gathering funds, they reached their first real objective, that was, the purchase of a plot of land on which to erect the building. Furthermore, in 1928, under pressure from a few Polish intellectuals, the council was forced to accede to the request of the committee of the building project and allotted a sum of 300 gold coins for the purpose mentioned. However, the sum was insignificant and ridiculous, but the council decision at this meeting was accepted only because of the Gentile vote, to the dismay of the Jewish representatives who were all from among the Rabbi's followers. In the decision it was noted, that at the appointed time, when the building would commence, the council would review the issue and discuss the request to increase their assistance, according to the extent and the need of the project, and the ability of the council. Although the contribution was a pitiful amount, yet from the point of view of local policy, the deed raised the profile of the young people in the eyes of the community, as they had succeeded in achieving an aim that was without precedent. The contribution of the council on behalf of the community, was something that other institutions, were unable to achieve. In 1931, the building was erected, and although it was not complete, it was possible to use. This was done, as stated, by a handful of enthusiasts who were not deterred by any obstacles.

The Nursery School (Parblubka)

I acknowledge that I do not know much about this important institution, except from a local community point of view. The essence of the founding of an institution like this in our town, points to the fact that a change was taking place in the awareness of the Jews in the town. A few years earlier, no one in the town would have dared to think of establishing an institution like this, that was not according to the way of life of the Chassidim. In 1929 this educational institution was established, that continued to grow. It is important to mention that this was a major change, and it is with considerable regret that I note, that people who could have been of assistance, did not see fit to devote their knowledge and experience.

Elections to the Council

After the Zionist workers accomplished their task, and the erection of the building “Bet Ha'Am “Dom Ludowy” was complete, these people simply became unemployed. To be a Zionist in a small town in Galicia meant that their ideals could not be realized, that they could not become whatever they wanted to be. However, after they proved themselves, and had acquired more self-confidence, of which they were deserving, the community saw that it was indeed possible to trust them, and that they could be relied upon. It was fitting to relate seriously to what they said, as they were not about to leave the social life of the town, were not preparing to emigrate to the Land of Israel, and intended to remain in the town. They were part of their society, deeply rooted in the soil of the town and involved with the people, yet they hesitated and remained uncertain about competing against the Rabbi's followers. Those who were more assured, relied upon two previous incidents that did not go well – one led by Advocate Krinshtein, and the second, the private initiative of Advocate Horowitz. These two experiences related to the election of a community committee but this time, there was one very energetic and the very intelligent person on this local committee

[Page 25]