|

|

|

[Page 455]

by Zvi Kadlabovski

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

The Linas ha-Tzedek [a social welfare organization] was founded before the First World War. One of the founders was Moyshe Nachman Sirkin's father. There was no formal community organization in our city at that time. The directors were men from the circle of merchants. They first created the Linas ha-Tzedek and then later on a hospital and an overnight shelter and hospitality center for the poor who came to the city so that they could have a place to sleep. After that we also had an orphans home. Among the community institutions that we had in the city, the Linas ha-Tzedek was an effective and necessary institution, thanks to Dr. Epstein, the apostate, who lived in Bielsk. He helped the Linas ha-Tzedek with his medical service which he provided without limit and without accepting pay. He was simply a member of the Jewish Linas ha-Tzedek. His wife was a Christian and his children knew nothing of Yiddishkeit, but he offered great help to Jews.

The Linas ha-Tzedek gave economic aid, medical help, and later on provided several beds for special Jewish patients who were ailing and needed special services and also for those who were ailing and did not have facilities in their home. This was one of the finest institutions that we had in the city.

We had another community institution–the overnight shelter. In those times, poor people would travel from one city to another. In each city they would go from store to store, from house to house, seeking alms. But they had nowhere to spend the night. So we created the overnight house and there they could rest and spend the night, then go on their way.

The Linas ha-Tzedek was associated with the “Balnitza” [Russian word meaning hospital], the Jewish hospital; the people who were most active were generally young people who would go to the ill and sit by their beds through the night. A person who was ill and had no one at home who could offer appropriate help or who could watch over him–someone would sit with him through the night, give him medicine, pay attention to him in case anything happened. The “Balnitza,” the hospital, offered help, real help, medical help.

A third institution that we had–all of this before the First World War–was a volunteer fire brigade.

[Page 456]

Dr. Epstein, the apostate [convert from Judaism], also served in the fire brigade. He was one of its founders. All of the volunteers were Jews, except that the leaders were all from the general population, the workers, because the fire brigade needed strong men for their work. People made uniforms for them, and the fire brigade was one of the finest institutions in our whole area. The had parades, had good gear, machines, and in the middle of the city there was a fire station where they kept them.

A little later on–with the participation of the intelligentsia, the non-Zionist intelligentsia–a library was created. They were not Yiddishists. In those days the expression did not exist. But some of them were socialists. The library was a general community institution, not a Jewish one. They served Christians and Jews together. Most of the books were in Russian, a smaller part in Yiddish. I do not recall any Hebrew books at all. Perhaps there were a few. The Zionists had very little influence over the library.

One cannot call the Jewish members of the library anti-Zionists, because at that time among the Jewish population there were no divisions of Zionists and anti-Zionists. One of the leaders was a notary, a non-Jew. Radkevitch was his name. He was a Christian, a liberal. We received support from him. The city council also helped.

At that time, only Jews who owned property could vote for the city council. Workers, everyday people who had no property could not vote. No elections were held in the days of the Russians. There were the so-called “five courtyarders,” the owners of five courtyards. These five owners assembled and chose several members of the city council. They had the right to choose a third of the city council. The other two-thirds were named by higher-ups. The library stood in a beautiful courtyard. It had a great many books and a reading room, and in the evenings people would come to read. There was a membership fee, and each member had to pay three rubles a year. With this fee he became a member and could take books home to read. There was a turnstile in the library. Later on, a proctor was hired, and even later there were two in the evening, one a Christian and the other a Jew.

The Jewish institutions had to be maintained by collected

[Page 457]

funds that were known as “karabke” [community funds]. The taxes were collected on kosher slaughtered fowl. Each housewife who went to have fowl slaughtered had to buy a receipt before the slaughterer went to work. She had to pay about five groschen for each bird. Then the slaughterer could do his job. Without that payment, slaughtering could not be done. For meat, one had to get a stamp at the city council, and this also had to be paid for. Part of the funds thus raised went to the needs of the Jewish community.

Our Jewish community organization in the city built a bathhouse. It was quite an old bath. It had to be refurbished. The Christian population also had no bathhouse, and so they battled with the Jews. They wanted to be partners with the Jews in the bath. The Jews in no way wanted to allow the Christians into the bathhouse, because they held that in the bath there would be a mikveh [a ritual pool], and that had to do with the Jewish religion, and a partnership with the Christians would interfere. Therefore they did not want to allow the Christians in. The Jews alone built the bathhouse and in the bathhouse they made two divisions: one was a regular bath for the common people, and the other, the better one, was called the “dvariansky” [Russian for “noble”]. The nobles were the higher class of Russian residents. The regular bath was very nice. It had tile and nicely built tubs. The foreroom was in the common section. In the better bath, in the “dvariansky,” section, each person had a private room. It was a very nice institution.

There was also a Jewish bathhouse attendant, and before bathing one had to pay.

Christians also used to go into the “dvariansky” bath and also had to pay. Jews and Christians also went into the common bath. Mostly they would heat the place on Thursdays and Fridays. In winter they would also heat it on another day.

[Page 458]

by Sh. Y. Stupnitski

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

Free Loan Organizations will always be sacred

The matter of free loan organizations belongs among those things of which men enjoy eating the fruit in this world but whose principal remains in the World to Come-as we say. [This is a reference to one of the opening prayers of the morning service, drawn from the Talmudic tractate Shabbat 127a.] One can understand this in worldly terms: One could say that a person gets enjoyment and more enjoyment from such loans, and that enjoyment will never be used up, because the “principal” always comes back to him, the principal will never be consumed. It is like a secular, material bush about which it is said that it burns and burns and burns and will never be burned up; the principal will never be consumed; the principal always delivers. Thus have Jews understood the matter of free loan organizations in the past. A free loan organization was sacred. A free loan organization always repays, even when a person comes to a halt, even when someone is-it should not happen to us-bankrupt. I have known of the unique perspective of the people toward the free loan organization since I was only a child.

|

|

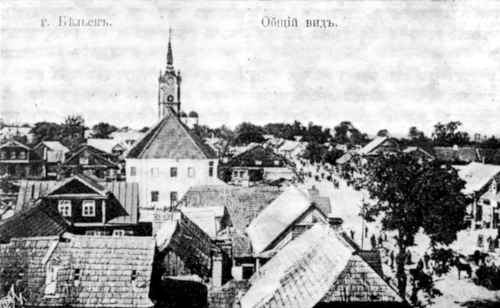

| General view of the city of Bielsk |

[Page 459]

How my father understood the free loan organization

To my father, a homeowner in Bielsk, would come a neighboring woman, Hinda-Beila, the keeper of a small shop, seeking an interest-free loan. She would come for the loan on Wednesday before the market and pay it back on Friday after the market. Thus it went for years. In time, her son Yechielke would also come for a loan. He had already, without objection, borrowed a whole twenty-five rubles and held onto it until Shabbos, once prolonging its return for a whole week. He also had credit for a long period. Once he came on a Shabbos night, sat down and discussed politics, about which he was an “expert,” and turned the conversation with my father to a project for which he wanted instead of a free loan, twenty-five rubles on a promissory note. He would pay interest. My father smiled and would not agree to this proposal: “You can have an interest free loan,” answered my father. “I cannot lend you money against a promissory note.” And Yechielke took the same twenty-five rubles as a free loan. When he left, I asked my father, “How come? For a promissory note you don't trust him, but without any safeguards you give him money?” My father responded:

People repay a free loan

“People repay a free loan. Even a person who finds himself in the worst situation will repay a free loan. A legal responsibility is different, especially a responsibility for which one has given an I.O.U. And if one pays interest, one's attitude is totally different. That's business, and it takes precedence; it's right to pay back, and if one cannot, it's right not to. Therefore, I can make a free loan and not be a moneylender, because with me that young man has no credit.”

In this way my father understood the matter of free loans as an iron principal that cannot be lost. A free loan must be repaid-this was a general axiom for Jews. Simultaneously, our parents held that a free loan is the most important mitzvah. In other words, our grandparents felt the social aspect of the mitzvah. And therefore in every city, in every Jewish community, there was a free loan office-as it is called today. Primitive and modest were its activities; The office was something of a mystery. No one knew who its officials were and no one knew who borrowed money from it, but the free loan office existed and

[Page 460]

as much as possible it helped those who had fallen, rescued them in need.

A free loan office in earlier times

I remember that in our shtetl of Bielsk-Podlaski, in the old beis-medresh, in a corner near the shelves of sacred books, stood a large oak chest, smeared up and ringed by iron hoops. The chest was old, truly as old as the beis-medresh. If someone climbed on the chest, he could reach the high bookshelves. One could reach the wall clock, and the ner tamid. Yeshiva boys would make a bed out of it and spend the night there. Young boys would hide out around the chest. No one knew what lay hidden inside the chest. We children began to make up stories about the chest. Once in the middle of the week, after everyone had said all the prayers, I saw how Reb Motya-Leib, a severe man, a big dairyman, went to the chest, opened the heavy locks and actually went into the chest, rummaged around, and finally pulled out a small parcel. I was curious and tried to draw closer, but that angry man gave me a severe look and I retreated. But my father quietly confided in me the secret that the chest contained the pledges of “Gemilut Chesed,” [lit. bestowing kindness], the records of the free loan society, and that Reb Motya-Leib was the person in charge, that he was taking out something that a person had pledged and now wanted to redeem. And actually a woman came out of the women's section, completely covered by a scarf, and Reb Motya-Leib gave her the package.

This was how the “Gemilut Chassadim Kase,” the free loan society, appeared to our fathers and grandfathers. It was something sacred, part of the beis-medresh, and it was under the protection of the community, just like the Torah scrolls, the sacred books, and other ritual objects. And when a person made his reckoning with the world and pledged part of his belongings to the “endowment” of eternity, it was self-evident that before all he meant the “Gemilut Chassadim,” the free loan society in the city. He could be certain that his principal would remain there forever, because it would be among those things of which “people eat the fruit in this world, but the principal remains in the World to Come.” It stays there for the distant future.

The old principal and the new style

In later times, it seems to me, that the age of the free loan society had ended and that people tried to reform, to change

[Page 461]

the old institutions, give them a more commercial character. We created the People's Bank with a nice location, a large staff, and competitiveness. Unfortunately, our “prosperity” did not last long. The bank quickly collapsed. There was a great uproar and we had to retreat to our former positions-as you would say in strategic terms. We held by the old free loan society, although it was no longer part of the old beis-medresh and people no longer took pledges. The old form had ended, but the substance remained the same. We trust, therefore, that the loans that one receives, even on a promissory note with endorsements, remains one of the things of which “people eat the fruit today and the principal remains for the distant future.” We trust, therefore, that the principal will not be consumed. But in order to fulfill this important duty, we need the capital, because “great are the needs of Your people,” because the need is great and with a small sum that the merchant or the worker receives without interest, with little effort whole families can often be sustained.

[Page 462]

by Moyshe Alpert

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

There was the old beis-medresh and a street named for it, Beis-Medresh Street; on Beis-Medresh Street there were three beis-medreshes and a Chasidic prayer house. Not far off was the courtyard of the bathhouse and the mikveh; on the street was the oldest beis-medresh, which was called “Der Alter,” The Old Beis-Medresh, and also the New Beis-Medresh. And there was also the “Hospitality” Beis-Medresh.

I remember only the sextons who were in the beis-medreshes. In “The Old Beis-Medresh” there was Reb Yossl the sexton. Actually Yossl Farber was from the family of Farber the Kalchuk. The assistant sexton there was the locksmith. In the New Beis-Medresh, the chief sexton was Moyshe-Aaron, and Yisroel-Simcha was the assistant. This was in 1908-1914, until the First War. In the “Hospitality” Beis-Medresh, Reb Shmuel-Moyshe was the chief sexton. He was a fine prayer leader, so people called him the “copper throat”; the assistant was, earlier, Issar the sexton and later on Duvid the bookbinder, Duvid Gurninski. Why was it called the “Hospitality” Beis-Medresh-because nearby was the hospitality guest house with accommodations for the poor. In the “Yafeh Eynayim” [Beautiful Eyes] Beis Medresh, Michel Kaplanski (Michel Goldschmit) was the chief sexton. He was a goldsmith. And the assistant sexton was Issar, my father. He never wanted to be the chief sexton, because one must call the chief sexton “Rav” and he must flatter him back, but, he said, I can sweep out the beis-medresh for everyone equally, wash the table off for everyone. Then it became known as Itzele's beis-medresh. Itzele was the first person who traveled to Greater Russia and Petersburg and worked so that Jews would be allowed to live in Bielsk. Because until his time, it was forbidden. He owned many houses in Bielsk. That is, in every corner of the city, there were his buildings. The trustee there was Baruch's father, from the Shtaynbergs. He was a descendent of Itzeke. Reb Maeir was the sexton there-the chief sexton. He was a fine cantor. And the assistant sexton was Alter (whose family I do not remember).

These were the beis-medreshes.

Then there was the Talmud Torah. Bielsk was a district center, so people came there from the whole district, from the whole area, to study. There were five classes in the Talmud Torah. The trustee was once Nachman

[Page 463]

the son of Zundl. When he left, Reb Chatzkl Lavital, the judge, became trustee. The first elementary teachers I do not remember. Next were Reb Yankl and Fishl the teacher. After them was Avram the teacher and Leibl the teacher. After Leibl there was Shimon-Velvel, a troublesome teacher in the first class. It was this way almost until the war.

I left Bielsk in 1920. Meanwhile, the teachers changed. After the war there was a yeshiva in Bielsk, a Novardok yeshiva [Novardok yeshivas were based on strict moral principles.]

During the war, the three beis-medreshes and the Chasidic prayer house were burned.

In the new beis-medresh, Yoel Landes was the trustee, followed by Reb Yankel Beils, Moyshe-Leib Daniel. In Itzele's beis-medresh, Shaya Shtaynberg (Aharon Shtaynberg's great-grandfather) was the trustee.

In Bielsk there were charitable institutions, like the Free Loan Society. People would spend the night with sick people. People would go once or twice a month, and people would give prescriptions or send a doctor. People would take bread and meat to the poor.

There was a committee, and it was decided that the poor would not go begging at houses. The poor would come and get a weekly sum, not a secret gift but something like a salary. The needy of the city also received each week a certain sum. They would come to the “Yafe Eynayim” Beis-Medresh in the lower prayer room each week before Shabbos. There were some who would come themselves to take their “salaries” and there were others to whom the trustees would give them. To bring into the room-hidden charity.[1] On the committee there were trustees and a record keeper. The trustees worked for no pay. My father Issar the sexton was the record keeper who handled the bookkeeping. There were poor people from elsewhere, from the local area, who came from all over the country, from Russia, so a measure was introduced that every three months each of them must come and take what was theirs. There was a file in alphabetical order, and according to the file, every foreigner received a half-ruble per month per person. At that time that was a goodly sum. There were some who received more, for instance the ailing and others. People could get as much as three rubles, a shochet, for example. Distinguished men received a bit more. And it was arranged that when anyone came to our town seeking a license and so on-he should use the opportunity to receive three months worth of pay. And there were some who would come into the city by train with their whole families, sometimes with ten children, and the father had to care for all of them.

[Page 464]

For women it was arranged that each seamstress would receive up to 4 rubles in order to buy what she needed.

For all these institutions my father was the secretary. After the First War also “Lechem Aniyim” [Bread for the Poor], led by Eliya Minbitzki and myself. Here we gave bread to anyone who came. The funds for all these institutions-for which my father served as secretary-was gathered from monthly contributions. This also operated via a file, in which was written how much each person was required to give-and we would send agents to the districts to collect the funds, just like taxes. Everyone worked without stopping. My father would give out the book with the records and they would go out to the districts to collect the money and update the records. The “Bread for the Poor” also operated in this way. Here we gave out bread and sometimes wood. On Pesach we would give either matzo or matzo meal-of matzo we would give 8 pounds and of matzo meal 10 pounds. And this was all voluntary. There was a storehouse and in the same neighborhood a bakery. Someone would come with a little list and I, in the storehouse or in the bakery, would give matzo or matzo meal. These were the community institutions in our city.

In my time there was also a burial society that took care to call a minyan for every funeral so that the dead should not be disgraced. For a large funeral, the whole city was summoned. No one who died in the city was overlooked by the burial society. There were times when I myself had to go to the gravedigger and call him for a burial at night. There was also a chevra kadisha [a group of people who prepared bodies for burial according to ritual laws]. Their members always stood by when someone was dying. This was a custom that supported a mitzvah. There were some interesting cases. I will tell you about one of them:

One Mendel was lying on his deathbed. His son Shmuelik called to him, “Papa, do you want to smoke a cigarette?” He said that he did. And the man, who was dying, sat up in bed, took his feet out of the bed, sat on it, and his son Shmuel handed him a cigarette. The dying man smoked while the chevra kadisha stood and waited. In short, it seems that the dying man sat and smoked a cigarette and the chevra kadisha stood around and did not know what to think. At that time there were long cigarettes with corks [that apparently acted as filters], and they lasted a long time. When the cigarette began to go out, a small kerosene lamp overhead

[Page 465]

was burning. The lamp also began to flicker. The dying man called out to the chevra kadisha, “What a coincidence. All three are going out at the same time-the chevra kadisha, the lamp, and...” Then he threw the cigarette butt on the ground, put his feet on the bed, closed his eyes, and...there was no one left to talk to.

My father was there.

Now I will tell another story that my father saw: There was a woman, a poor woman, who was dying. My father was standing near her. He had brought a doctor, and the doctor was a German who was writing a prescription that cost three rubles. My father asked the doctor, “Doctor, how long do you think this woman can go on?” The doctor said, “About two hours.” My father thought about it and said to the doctor, “Listen, you yourself say she will live perhaps two hours. Even if she were wealthy (remember, this was 70 or 80 years ago) that would be a lot of money. Even for a rich person it would be a shame to throw out money. This is a poor household that survives on what the community provides. Should you be writing such an expensive prescription?” The doctor thought about it and said, “How can you judge the value of an hour's worth of life. If a person lives for an hour and the pulse goes on, there is still hope. How much would a person pay to go on for another hour?”

My father stood there and said to the doctor, “You're right”

There was a trustee named Sirkin, from the well-known Sirkins. Nachman Sirkin's father was also a trustee. We had custom that on the eve of Rosh Chodesh Shevat there would be a banquet for the chevra Kadisha. Elsewhere people do this on Rosh Chodesh Adar, which is a minor fast day. People would pray at the cemetery and then in the evening have a banquet. It would be for men separately, for women separately, and for children separately.

Nachman, the trustee of the chevra kadisha, would do tricks. He would put a glass of water on his forehead and walk through the banquet around the tables, singing and dancing, mount a chair or a bench with the glass of water on his forehead and never drop it.

Editor's footnotes

[Page 466]

by Tz. Kadlubovski

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

A People's Bank, a branch of a central bank in Poland, was created in Bielsk immediately after the rise of Poland after the World War. Such an institution was needed because in Bielsk there were many workers and also a large number of merchants who from time to time needed a loan. Because they had no capital, the leaders of the artisans and the merchants got together and created a bank. We received a loan from the central People's Bank of all Poland in Warsaw. The bank served and belonged to the small artisans and merchants. Larger concerns had another bank, the Kupietsky Bank–the bank of the merchants. But people like us could not start things so quickly and easily so that the bank would function, so we got together with other cities in the area and we later created in Vilna a second central bank independent of the Warsaw bank. Another reason was because the Warsaw bank did not want records written in Yiddish. This was in 1921-1922. The People's Bank was one of the greatest aids to the population.

|

|

| 1920-1925, Board of Directors of the Jewish People's Bank in Bielsk Podl |

[Page 467]

Thursday was for us the market day. Many people came into the city from the surrounding towns and villages. People hoped on that day to have lots of sales and income. Just like today, people used to buy things on credit, and on the bills it was written that they would be paid off on Thursdays. But what could people do if a Thursday turned out to be not so good, or if it was a holiday? When the bills were written, people did not take such things into account. It would be a catastrophe. People would be bankrupt, and their credit would be lost. So we arranged that what the Jews took in for the whole week they could bring into the bank. The promissory notes that they had signed were sent to us and we paid them. In this way the credit system supported the merchant and the worker.

Another help to the city that we received from the Polish government bank in the city was a loan that was given generally only to private merchants or to another bank. We received this thanks to good relations and protection, and thanks to this we felt strong even in comparison to our central bank. Our bank always gave loans and operated nicely. A managing committee and advisory board for the bank were chosen from among the members. The director was a salaried employee, and aside from him there were 3-4 other employees. Those who were elected worked for the bank without pay. For the elections to the board and the council there was a battle between the workers and the merchants, but the work of the bank proceeded harmoniously.

Thanks to the democratic development, a union for the artisans was also created in the city. Since I remember, the artisans in the city did not have an independent union. But the democratization of life and there having been pulled into the community life gave them the impetus to create their own artisans union. One of their activists was our friend Chana Chashkes, a member of Tz'irei Tzion[1] and later of Poalei Tzion[2], a member of the community organization board, a member of the People's Bank, a shoemaker who lacked higher education but who was very intelligent. He held by no dogma, but he could quickly grasp and understand logical arguments. Because of him, many of the overlooked artisans in the city became involved in community life. They became followers of education, whether Hebrew or Yiddish, and they took part in various community activities. With them, their organization became strong and well known.

The general Zionist organization had existed even before the German occupation, but it had been shut down. There were

[Page 468]

only a few activists and not too many activities. The activists never left their comfort zone. As the movement for democracy began among the people, the Zionist movement began to increase. Tz'irei Tzion, for example, had an office with several rooms in the center of the city. Gatherings were held 4-5 times a week, attended by over a hundred people, whereas before they had had only 10-12 people, because they were a closed group. They were devoted to Hebrew education. Among them were Menachem Stupnitzki, Ephraim Melamedovitsh, Yakov Appleboym, and before them–Yakov Beilis and Radzilevski. The latter were the first pioneers to make aliyah to Eretz Yisroel. That was in 1920. People made a beautiful banquet for them, and that gave stimulus to the Zionist movement.

Before the war, we had only two banks–the bank of Krivianski, a Jew who had started to create a bank for the Russians, and for Jews he had created a second bank through a good Jew whom people called “the rabbi.” Thus in Bielsk, which was a commercial city, there was a tradition of banks. The city had a market and a large hinterland, a business city with a large periphery. In addition, Bielsk was the main city of the district, which also had an effect on its economic life.

Editor's footnote

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bielsk-Podlaski, Poland

Bielsk-Podlaski, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 6 June 2023 by SK