[Page 175]

He–Halutz

Translated by Sheli Fain

[Page 176]

Blank

[Page 176a]

|

|

Photograph no. 52: Poalei Zion and Tzeirei Zion United Council, Bucharest, January 27, 1936

1.Dr. Sh. Entzer, 2. I. Shitz (Magen), 3. Givoni, 4. Dr. A. Tartakover, 5. M. Orchovsky, 6. Dr. I. Beider, 7. I. Krasnushensky, 8. M. Kotliar, 9. A. Reiss, 10. H. Geler,

11. M. Schwartz, 12. K. Grunich, 13. D. Vinitzky, 14. Dr. M. Kotik, 15. Dr. Tz. Helner, 16. A. Rabinobich, 17. Z. Rosenthal, 18. Dr. N. Fidelman, 19. I. Koren, 20. I. Michali,

21. Petrushka, 22. I. Geler, 23. Sh. Bronshtein, 24. Tzukerman (Naamani), 25. I. Vinitzky, 26. D. Fistrov, 27. Manieli, 28. M. Rolel, 29. M. Lerner, 30. K. Zager, 31. A.R. Meir,

32. B. Milgrom, 33. I. Gluzman, 34. Sh. Potik, 35. I. Hurman, 36. M. Kolker, 37. Frish, 38. Tz. Weisenberg (Atzmon) |

[Page 176b]

|

|

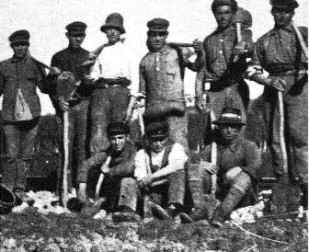

Photograph no. 53: A Hachshara (Training) Group from Ataki and Mogilev–Podolsk at the Dumbraveni Farm 1918

From right to left: sitting: D. Heler, Bronshtein, Naslavsky, Englander, K. Sha'Tz

Standing: I. Tzarevnik, Podgayetz, A.L.Tlitnik (Ben Arye), I. Hazan, Diamant (Shochem) |

|

|

Photograph no. 54: First Hachshara Group from Faleshti 5679 (1919)

–names on page 331 from a letter sent to the Zionist Executive in London Tzi Kuperman, Yakov Shneider, Eliyahu?, Moshe?, Tzvi Farber, Yakov Tuver, Pinchas Leron, Zachariahu? |

|

|

| Photograph no. 55: First Hachshara Group from Faleshti 5680 (1920) |

|

|

Photograph no. 56: First Group of Halutzim from Akkerman Arrived in Eretz Israel 1921

From right to left: sitting on the ground: N. Tzukerman (Naamani), A. B. Serper, A. Brand

Standing: Ab. Margalit, I. Brener (Harari), I. Sh Rabinovich, A. Kaminker (Kamin), Ab. Dorfman (Kafri) Ish. Botoshansky |

|

|

| Photograph no. 57: First Hachshara Group from Orgheiev 5680–81 (1920–1921) |

[Page 177]

First Steps[1]

The February 1917 revolution liberated the Russian people from oppression, including the Jewish people, who hoped to shed the chains of tyranny and discrimination that shackled them since the outbreak of WWI. The Zion fighters came out from the underground proudly flying the blue and white flag. At the same time the Balfour Declaration provided the framework for establishing a Jewish home in Eretz Israel. The two events caused the Jewish youth in Eastern Europe to organize the nationalist Zionist movement and apply the ideas of the general revolution to their own lives and reinvent them with a Jewish national character.

To achieve the goal of living in their own land they had to undergo physical, professional, vocational, and moral transformation.

The first sparks of the Zionist movement came from Bessarabia, where Jews were used to agricultural work. The rural communities of more than 8,000 Jewish families worked the land and kept close to Jewish traditions but also dreamed of salvation in Eretz Israel. Jewish rural youth naturally were among the first to join the He–Halutz (pioneer) movement.

The first Hachshara (training) groups started organizing in 1917 with Shlomo Podgayetz from Ataki (Erd und Arbeit, no.1, Kharkov, 11–24 February 1918) after he participated in the He–Halutz Council that met in Kharkov on January 15–18, 1918.

The number of Hachshara groups grew in the spring immediately after the annexation to Romania. The authorities were suspicious of the groups and their ties to the Russian revolution and first started arresting members of the Tzeirei Zion group in Kishinev that had been training in a neighboring village. Fearing arrests, the Soroca group with the majority of members from Ataki and Mogilev–who were training in Dumbraveni[2] mainly in bee–keeping, tobacco, and gardening–were forced to dismantle. The agricultural group from Faleshti and the Capreshti groups (light industry and then agriculture) had better luck and were free to keep going (see letter to the Zionist Federation in London, Appendix, p. 331). These two groups had been established in the spring of 5680 (1920) and continued their training in Kishinev.

At the end of 1920, before authorities imposed limits on immigration, a few people immigrated to Eretz Israel: four from Ataki[3], seven from Orgheiev, nine from Faleshti and a few from Capreshti and Calarashi.

At the same time, the group of 11 people who trained in Akkerman[4] joined the 7 people from Bender[5] who were graduates of the Hebrew Gymnasium managed by Tz. Shwartzman. These pioneers included Moshe Postman, who was one of the founders of the Tzeirei Zion after the 1917 Revolution and had a great influence on the youth movement of Bessarabia.

[Page 179]

It's impossible to name each person who made Aliyah, but every settlement in Eretz Israel was involved in absorbing the newcomers. By March 1919, 115 pioneers from Russia had arrived by boat to the port of Jaffa. (H. Berlis: The Third Aliyah, p. 79).

Because of the October revolution, the civil war that followed, and the pogroms in the Ukraine many Jews fled to Bessarabia, including many Halutzim. Starting with the spring of 5680 (1920), practically every town and city in Bessarabia and even in Bucovina received the pioneers, who became hard–working role models for the local youth and helped build the foundation of the youth movement.

In the same spring of 1920, Tzeirei Zion established a special council to deal with the immigration. At the First He–Halutz[6] Congress (Kishinev, May 4–8, 1920), I. Ydelman gave a lecture regarding the He–Halutz plans followed by the Congress' decision to register He–Halutz as an autonomous agency with the local court.

A more in–depth discussion about the Tzeirei Zion organization and programs took place at the First All–Romanian Tzeirei Zion Congress, Jassy August 24–28, 1920.

When the representatives of the Poalei Zion, Itzchak Kaspi (Zilberberg) and Chaim Shorer, came to Kishinev they helped to establish a temporary Central Committee[7], which was led by members Nachum Tulchinsky (Tal), chairman; Leib Glantz, vice chairman; Itzchak Kaspi and Chaim Shorer, secretaries. Other members of the Committee were Eliyahu Ortenberg, Chaim Borodiansky (Bar Dayan), Akiva Globman (Govrin), Itzchak David Zilber, Joseph Cohen, Zmira Seminovskaya, Asher Koralnik, Itzchak Rosenberg, and Itzchak Shwartz.

[Page 180]

The Beginnings

The Committee's first activities related to creating the political, economical, and legal conditions for immigration. The main concern was to solve the situation of the Jewish refugees from the Ukraine, who were already trained when they arrived but used their stay for more training. Immediately a group of Ukrainians was organized for immigration.

The Committee also arranged for training the growing number of Bessarabian youth groups. In Kishinev and later in Orgheiev, Soroca, and Bender the Committee established “He–Halutz Homes,” where the youth learned to live in communal conditions and work in preparation for immigration.[8]

The halutzim settled to work in the colonies organized in Dumbraveni (a group from Yampol was among them), Artujeni Marculeshti, Beltz, and Calarashi. The group that settled in Soroca worked in the vineyards, but because of the droughts, did not last there very long.

In Circular No. 1, dated February 15, 1921, the He–Halutz Centre outlines the pioneer ideology:[9] “We are ready for any work, we can live in difficult conditions, we are happy with a small pay, and we are courageous in the national arena. We are ready to build our land and sacrifice for it. Beware of immigrants who complain and who come with demands to our institutions and then leave the country.”

[Page 181]

In January 1921, the General Secretary of the Zionist Executive, Dr. Landman, came to Romania to assess the situation of the thousands of Ukraine refugees and to facilitate their immigration to Eretz Israel and other countries. He tried to improve the refugee situation, especially concentrating on refugees in Galatz and helping them immigrate to Israel.

Leib Glantz went to Galatz to negotiate with Dr. Landau and organize the refugees who were pretending to be halutzim in order to emigrate. He–Halutz Centre was very serious about who was being selected to immigrate to Eretz Israel. Because the economic situation in Eretz Israel was not very good, the Centre did not want any refugees without training to immigrate. They were following the directive of the Labour Ministry, the Ha–Poel ha–Tzair and the immigration department of the Zionist Federation in Vienna.

The agreement with the Central Committee in Galatz gave priority to the people recommended by He–Halutz in Kishinev. It also agreed to open a He–Halutz Home for 80 people. Glantz, Dr. Landau, and A. Markus from the Zionist Federation of Romania spoke at the official opening.

Dr. Landau had visited Kishinev and was impressed by the He–Halutz Centre activities and by the pioneer spirit and promised to work towards better cooperation between the Romanian Zionist Federation executive and He–Halutz regarding immigration.

At the same time, Eretz Israel councils opened in Kishinev, Chernovits, Bucharest, and Galatz (later moved to Constantza). The Zionist Centre in Kishinev met on 9 Shevat 5681 (1921) and decided on the role of the He–Halutz: a) He–Halutz will be an independent institution; b) the Eretz Israel Council would approve the immigration lists recommended by He–Halutz; and c) appeals about denied permissions would be sent to the Eretz Israel Council, which would assess all requests and forward them to the He–Halutz for approval.

The Council in Galatz tried to interfere with the activities of the He–Halutz Home, which

[Page 182]

caused a bitter conflict with the He–Halutz in Kishinev that brought the matter to the Eretz Israel Council main office for discussion, and the instigators were fired from their positions as stated in a letter from He–Halutz of 15 Av, 5682 (1922) signed by E. Globman (Govrin) and I. Barafael to the Vienna He–Halutz organization.

Delays and Breakthroughs in Immigration

The unemployment caused mostly by the lack of investments in Erets Israel together with the decline in the immigration budget almost resulted in the closing of the Eretz Israel gates. Also the Zionist Executive[10]'s decision to closely monitor the immigration fostered a lot of anger in those who wanted to enter Eretz Israel. The Zionist Executive[11] refused to offer travelling money and other aid to the immigrants. The population in Eretz Israel became dissatisfied because they were counting on the Labour movement to help ease the immigration crisis, hoping that “immigration will bring work, and immigration will lead to liberation.”The Ha–Poel Ha–Tzair decided to “Break the Immigration”[12] and sent special envoys to encourage the Labour movement abroad to gather and train the groups who desired to immigrate.

[Page 183]

The correspondence of the He–Halutz Centre and the London Zionist Executive Committee describes in detail the situation and conditions of the Halutzim who were stranded in Bessarabia and the situation of the Labour movement (Appendix, p. 332–335).

At a meeting of the halutzim in Kishinev where 200 people participated, I. Lishevsky, B. Slifoi, M. Livshitz, and Chaim Shorer drafted and sent a letter to the London Zionist Committee:

“The halutzim who come here are dedicated and know how to overcome the present adversities. They know how to find and to secure new work places in places where no employment existed before; they know how to organize their lives in all kinds of difficult situations… We are aware that the continued flow of immigrants will bring employment and we demand: Clear the way and the hurdles for the halutzim; we will immigrate despite the difficulties and sufferings.”

Dr. A. Katzenelson from Constantinople observed in his letter of 20 Shevat 5681 (1921) that only organized groups from Bessarabia arrived in Turkey. Immigration also increased from Chernovits, where a large mass of refugees succeeded in crossing from Northern Bessarabia.

Letters from the He–Halutz Centre to the Executive of Ha–Poel Ha–Tzair in Jaffa read: “The events that happened in Jaffa force us to take steps in order to enlarge the immigration of the halutzim. We decided to increase the number of immigrants who came here without ‘requests.’ The political situation is comfortable for us. Please send us the requests without mentioning numbers, and we will complete them. These days the third group of 45 people without ‘requests’ are leaving.” (Letter no. 118, signed by: President I. Bashrovker and Secretary M. Gutman.)[13]

[Page 184]

Letter no. 212 from 23 Iyar 5681 (1921) reads “We already appealed to you on the matter of increasing the immigration. Few ‘permits’ are issued to people who are officially requested by the Council. Here[14] we only need to have a request with the signature of the Labour Federation. Therefore we would like to ask for 50 requests each one for 20 halutzim. It will be beneficial if you issue 10 requests a month, etc.” (President I. Bashrovker and Secretary M. Gutman).

At the same time, more obstacles appeared in the immigration process. The boat “Dalmatzia,” carrying 98 halutzim from Romania among the 158 immigrants, that arrived to Eretz Israel during the riots of May 1921 was not allowed to dock even though the halutzim had the proper documents. Because the British government stopped the immigration, the boat was moved from Jaffa to Haifa and then to Alexandria for three day quarantine; after that it was returned to Constantinople. This ordeal did not break the halutzim's optimism and the desire to immigrate.

The immigration ban caused a wave of protests all over the world. The British Government bent under the pressure exerted by the Zionist movement and decided to allow entry to Eretz Israel to those who had already received visas up to the ban. In the middle of June 1921 the British director for immigration, Major Moris–with the participation of Chaim N. Bialik, A. Droyanov, M. Kleinman, and I. H. Rabintzky, who came from Odessa–organized a meeting at the Eretz Israel office in Constantinople to assess the situation and make sure that the visas were in order. The visit of Major Moris is described in a letter that the Eretz Israel office sent from Constantinople to the Zionist Centre in Kishinev.

[Page 185]

Letter 608, 20 Sivan 5681 (June 26, 1921): “Major Moris did not come to allow the immigration; he is here to stop it. After he spent a week with us, we understood his intentions. He only allowed 50 people (from the 5,000 who were waiting here) to immigrate, and after that another 24! The rest of the refugees are left here without the hope that they will be allowed to immigrate. After he checked all the people, he expressed doubt about the work of the Zionist Federation. He claimed that the Federation does not have the clout to check the political status of the immigrants and that he fears adverse elements might be among them. He claimed that the Zionist Executive should have worked under special supervision in order to vet the immigrants. We did not see any desire from his part to understand our situation, and his distrust insulted us deeply.” (Appendix p. 336)

At the end of the letter: “Tomorrow, Major Moris will leave for Galatz, Kishinev, and Bucharest in order to examine the situation there. We suggest that our friends there should stand on their positions and defend the work and the honour of the Federation and explain to him the situation. We hope that all these depressing results of his visit will bring changes for the better.”

In Romania, the British Consul supported the immigration and was in favor of the “Return to Zion” endeavor. He had friendly relations with Yulian Zilberbrush, the director of the Eretz Israel office in Chernovits, and with the secretary of the Labour Department, Advocate I. Bar–Shira. He provided entry visas to the halutzim who were gathered in Galatz to wait for immigration. To speed up the process, the consul hired a few young typists from Chernovits to help his secretary.[15]

[Page 186]

The situation became more dire when in July 3, 1921 the British governor gave new directives for issuing visa certificates that had been in use since December 17, 1920. The new directives cancelled the right of the Zionist Executive to issue visas and transferred the visa activities to the consulates of the various countries. The directives put the immigration of the organized groups who were waiting in Galatz and Kishinev at the discretion of the consuls.

Chaim Shorer, from the He–Halutz Centre in Kishinev writes in a letter of Tishrei 5682 (1922) to the Labour Department in Eretz Israel[16]: “From the 100 people with ‘Requests’ who enter the Consul's office, only 30 receive the visas, as a result of the July order. There are people who came to the consul for the fifth or sixth time and every time they left empty handed. Even yesterday the consul denied the 20 visas which were approved earlier. The people left in misery not knowing when and who will be granting them entry to Eretz Israel. It is heart breaking that these people who are so needed in Eretz Israel have to suffer so much. Why don't we wake up and come to their rescue?!

These are the prospects of immigration we face now and we cannot deny that this situation influences the spirit of all our activities. Even the hachshara (training) activities suffer and we cannot raise the money necessary for training because the public regards it as a futile exercise, since they are not allowed to immigrate. Because of lack of funds, we decided to restrict the training to a few locations and bring there the halutzim from their hometowns. In one location we are organizing now a farm of 40 hectares.

We would like to emphasize that we are going to work toward turning Romania into a transit place for the refugees from Russia and also instill there the interest for Eretz Israel.”

[Page 187]

At the meeting of the He–Halutz on Shvat 5682 (1922) the executives L. Glantz, N. Tulchinsky (Tal), and I. Skwirsky expressed their rage against the immigration ban: “He–Halutz does not recognize the foreign ban and it will use any means to continue the immigration.”

They sent a telegram to the London Zionist Executive, which said, “The He–Halutz Executive in Romania wants to point out that the Executives in London do not understand how important the immigration is. Therefore we have to consider all methods to continue the immigration.[17] The Executives agrees that only free and steady immigration of pioneers will provide the economic and political foundation in the country. We promise to use all necessary methods to open the immigration gates.”[18]

Despite the difficulties, 10 organized groups of halutzim, or about 982 people, arrived in Eretz Israel from Romania by Pessach 5682 (1922).[19]

The Deterioration of the Legal Situation of the Ukraine Halutzim

In November 1921, the situation of the Ukraine refugees in Bessarabia took a bad turn, and it became urgent to transfer the refugees with temporary documents from Bessarabia to Romania. Braila and Galatz, two port cities in Romania, were used for the transfer. About 100 members of the ninth group were already waiting there for many months. The “evacuation” operation needed money for travel as well as work places and homes for the refugees. I. Rosenberg and Akiva Globman were in charge of this undertaking assisted by Engineer Ernest Levy, the Secretary of the Eretz Israel Centre of the Zionist Federation in Bucharest.

[Page 188]

In Erd und Arbeit 12, of 10 Kislev 5682 (1922), A. Globman (Govrin) appeals to the Bessarabia youth to take the place of the Ukraine refugees: “We are leaving, but you have to refill our ranks.” The moment the Ukraine refugees left, the youth of Bessarabia started to join the He–Halutz, at first not very organized but slowly turning into real halutzim, followers of the Zionist ideology.[20]

The Romanian (Regat) Zionists Come to Help

The Executive decided to close the transit location in Constantinople and transport the refugees directly from Romania. At the Bucharest Congress on November 8, Itzchak Rosenberg[21] appealed to the Romanian Zionists to raise new funds.

The port of Galatz received the halutzim with open arms. The old people still remembered the migrants from Moineshti and Birlad who laid the strong corner stone of the first settlements in Eretz Israel.

The ninth group was the first to leave directly from Galatz.[22] The organization had to raise large sums of money for the transports, which for the 10 groups cost more than 1,500,000 Lei, or about 6,000 Sterling Pounds, a great deal of money at the time.[23]

Tzeirei Zion imposed a self tax and raised about 78,263 Lei.[24] The proposal to institute an “immigration tax” was not accepted, mainly due to conflicts with the fundraising campaign for Keren Hayesod.[25]

Footnotes:

- He–Halutz is a Romanian branch of the Bessarabia Zionist Federation. The headquarters were in Kishinev from its inception until 1932 and then moved to Bucharest. This chapter discusses the HeHalutz in general. The author could not discuss other Halutzim organizations because of a lack of documents. These organizations are mentioned only for their training activities which helped secure immigration permits (certificates). Return

- Erd und Arbeit, Kiev, No.6–7, Tamuz 5675 (1915) and Ha–Poel Ha–Tzair, 14, 5679 (1919) Return

- Two of them, Eliezer Talitnik (Ben Arye) and Issaschar Tzarevnik, went to Kibutz Eyn Harod. Ben Arye became later one of the founders of Kibutz Kfar Vitkin, and Tzarevnik went to Yagur. Return

- In 1933 N. Tzukerman and Abraham Cafri (Dorfman) founded Moshav (colony). Kfar Hess and Yeshayahu Berger (Harari) became members of Moshav Eyn–Eyron. Return

- At the end of the training in July 1920 a group including David Weiser (later manager of National Insurance branch in Petach Tikva) joined the Akkerman group (including B. Raptor). They were joined at the Moshav Mesilah Hadasha (the New Path) near Constantinople by P. Bendersky, his wife, and sister–in law. They arrived in Eretz Israel on the Mahmudiah boat on November 14, 1920. Return

- Circular B of the Tzeirei Zion in Bessarabia, Nisan 30, 5680 (1920) Return

- He–Halutz, Special Edition. Kishinev, 14 Nisan 5682 (1922) Return

- The most famous He–Halutz Home was on 20 Benderskaya St., corner with Alexandrovky in the building given to He–Halutz by Rabbi Shmuel Beltzen. Many people wrote about 20 Benderskaya, among them: N. Cohen–Tardion, L. Glantz, Z. Rosenthal, Sh. Hilleles, Chaim Shorer, etc. They wrote about the life, the events, the festivities that took place there, and the visitors. Return

- Erd und Arbeit, no. 4, Kishinev February2, 1921. See Appendix p. 337–340 Return

- In a circular from July 1919 the Zionist Executive wrote: We have to publicly acknowledge that the immigration to Eretz Israel has to stop for the present time. Until the country is open again to immigrants only the following categories will be admitted: a) people who have already lived here or have families and properties; b) representatives of organizations that have worked for building the nation; c) artists and specialists; d) people with a large amount of funds, who can be settled immediately–Dan Pines, He–Halutz in the Revolution Furnace, p. 72 Return

- Hapoel Ha–tzair, no. 17, February 4, 1921 Return

- Tzvi Livne (Liberman):The Third Aliyah, 5718 (1958), p.16 Return

- The two signatories are founders of the He–Halutz in Bucovina; they live in Israel–Advocate Bar–Shira and M. Beniyahu. Return

- Chernovits was the location of the British Consulate. The consul, Sir Cameron, was a noble man who respected the Jewish national dream. He had friendly relations with the community representatives. He readily answered all requests for immigration. Compared with the British Mandate administration in Eretz Israel, he was a righteous gentile. Return

- Testimony of M. Benayahu, secretary of Ha–Halutz in Chernovits Return

- See “Hapoel Hatzair” chapter 12, p 92–94 Return

- They received 16,000 visas in the first year, which were not used. From the 1,000 approved visas, only 100 were sent to Romania. Return

- Erd und Arbeit, 24, Adar 5682 (1922) Return

- Arye Rafaeli (Tzantzifer) in his book, The Struggle for Redemption p. 170–174, mentions that the groups were from Russia and Ukraine when in fact many were from Bessarabia (starting with group no. 6). Return

- Leib Glantz, leader of He–Halutz Bessarabia for six years, wrote in Undzer Tzeit, Kishinev, August 1933 on the occasion of the 18th Zionist Congress about his love for Jewish Bessarabia and her sons and daughter, the halutzim from Jassy, Biliceni, etc. and his hope to meet with them in Eretz Israel. Return

- Erd und Arbeit, 12, December 12, 1921 Return

- Hapoel Hatzair, 8–9, December 30, 1921. Chaim Tzasis reports that the halutzim from Vertujeni left Galatz in the boat named Colombia and arrived in Eretz Israel on December 19, 1921. Return

- He–Halutz, special edition of The He–Halutz Week, Kishinev, Pessach 5682 (1922) Return

- Cicular, no. 9 of the Tzirei Zion Executive, Kishinev January7, 1925 Return

- He–Halutz, special edition of Voch fun He–Halutz (The He–Halutz Week), Kishinev, Pessach 5682 (1922) Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

The Jews in Bessarabia

The Jews in Bessarabia

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 24 Aug 2020 by JH