|

Zionist Organization and its Branches 1917

|

|

[Page 17]

[Page 19]

The First World War brought the Zionist activities to a standstill in the entire Russia, because: a) the totalitarian regime prohibited all political activities; b) of the need to organize assistance to thousands of refugees and displaced people who arrived from the areas near the front.

Among the first refugees who arrived in Bessarabia were the Russian subjects who were deported from Eretz Israel. The first groups arrived on 25 December 1914, via Romania and settled mostly in the Ungheni border area. Even though the locals,especially the local youth, immediately organized assistance, housing, food, clothing and travel money to a desired destination[1] it was necessary to do a special fundraising campaign all over Bessarabia to help the refugees. Except for this direct help to the refugees from Eretz Israel, who arrived in Central Bessarabia, the Jews of Bessarabia did not collect money the way it was done in the rest of Russia. The 539 communities in Russia that contributed to the fundraising collected 371,369 Rubles and another 120,626 Rubles were collected from individual donors. Among the 539 communities, 18 were from Bessarabia and they collected 11,489 Rubles[2], an average of 638 Rubles per community compared with 449 Rubles in other districts.

From the start of the War, the Zionist movement was forced out and the leadership was arrested and exiled. Among the detainees from the Russian Zionist Congress that took place in Odessa on May 31, 1916, who were deported to Tambour, were also representatives from Bessarabia: Israel Skwirsky, Leib Trachtenberg, Yakov Massis and the teacher Gindin.

In 1916, the Zionist activist Israel Blank from Bender was brought to

[Page 20]

trial because he had in his possession Zionist propaganda material, booklets of stamps and Keren Kayemet collection boxes. He won at the second appeal in Kishinev[3].

Footnotes:

Already at the beginning of the war in 1914 when brigades of Circassians arrived in 13 villages of Bucovina and Bessarabia near the Austrian border, the life of the Jewish population of about 2,700 people became unbearable. On August 17, immediately after their arrival, the Circassians started looting the Jewish stores and homes without any sanctions from their commanders. The suffering population hoped that with the advancement of the front on the Austrian territory, the misery wouldn't last long. When the Russian army was defeated by the Austrians and started to retreat towards Russia, brigades of Cossacks appeared in the area and the situation worsened.

The commandment of the Russian troupes, which did not trust the Jewish population, took urgent measures to deport the population from near the front. They did that on the Baltic front, on the Poland front and lastly they applied it to the Bucovina front. On 27 March 1915 an order was given to immediately deport (within 6 hours of the order) the entire rural Jewish population.

Within one hour of the order, the Jews lost everything: the stores, the shops, the fruit storage (apricots, nuts, apples), the facilities to dry fruits (black plums), and the warehouses[1].

At the beginning, the refugees concentrated in Khotin; from there they went southward to Beltz and Soroca. Where ever they arrived the refugees got help from the local Jewish population. In addition, the communities gave donations to the Central Relief Fund in Petersburg for the assistance of the refugees from Poland and the Baltic states.

The events and the relief efforts that followed pushed the Zionist activities to the side.

Footnote:

[Page 21]

The February, 1917 Revolution provided equal rights to all citizens and ignited the national awakening among the ethnic groups of Russia. Even the 5 million Jewish people who were oppressed and exploited started to dream about a new life. On 21 March 1917, the “Provisional Government” issued an order to remove all religious, political and national barriers. This caused the renewal of the Jewish public and Zionist activities. This greatly revitalized the national movement that encompassed many levels of population, but especially the youth groups.

The first circular letter of 12 March 1917 of the Zionist Council in Odessa (also responsible for Bessarabia) and signed by Menachem M. Ussishkin reflects the sentiment of the time:

“Great events happened. Immense possibilities for freedom and for a life of happiness are opening for all the nationalities living on the Great Russian soil. Finally, good fortune will come to our long suffering people and in freedom it will strengthen its broken back and will stop being subjugated and oppressed. We will join forces to create and built and organize our Jewish community in Russia for the development of the economy and culture. –––

We obtained individual freedom. Now our duty is to obtain national freedom – to found an independent political centre in Eretz Israel. –––

Let's all work together to return our two thousand year old dispersed people to our historical land, to our homeland, to gain national and political independence.”

The Zionist Council in Kishinev distributed a proclamation to the entire national movement in Bessarabia and called everyone to come together under the Zionist movement flag, which continued its work even under the duress of the Tsarist regime and to participate in the fight for elections to the local city councils, to the community organizations and to the All–Russian Constituent Assembly.

Here is the text of the Proclamation:[1]

Brothers!

This great historical hour in Russia presents the citizens with the opportunity to systematically organize for the newly created independent action. The tremendous events which happened lately solicit common, organized and forceful action from our Jewish brothers.

[Page 22]

It is our duty as Jews to devote our hearts and souls to the strengthening of the new regime. We have to ally ourselves with the progressive and democratic forces in the fight for the prosperity of the country and for the bright future for all the nationalities. Beside the general problems occurring in this country, we also face special important Jewish national problems: to achieve our independent autonomy based on general direct and secret elections; to establish national schools and to reorganize the dwindling public institutions.

The establishing of our national homeland in our ancestral land, Eretz Israel, presents an extra problem of great importance to us. There, our ancient people will be able to decide its future destiny, to create a national culture and to show to the entire world the talents, the brilliance of our soul in all its splendour.

Our dream which we carry through the shadows of generation, through the bonfires of the Inquisition and the tortures does not look as a legend anymore – it became now a real thing, closed to reality. Our duty as Jews whose pride did not leave our hearts is to strive to accomplish this national vision. “Forward under the Zionist flag” – this is today's slogan that should lead the free Jewish people in every city and settlement.

The Zionist movement, the only national organization on the Jewish street that existed even during the Tsar and the dark persecutions is calling on you, Jews of Kishinev, to come and unite under the blue and white flag. Right now the Zionist Federation is free to expand and intensify its activities.

Dear brothers join our ranks! We will work together, united and organized and we will win the local councils elections, the election to the parliament and autonomy for our community.

Right now in Kishinev we are facing elections to the Zionist Congress to the general congress of representatives of the Jewish Communities that will work to solve an entire series of important national problems and especially the issues linked to Eretz Israel.

As you know, only members are entitled to participate in the elections for Congress. Hurry and register as members of the World Zionist Federation – and vote. Please answer our call and we will fulfill the prophecies of our great prophet: “hear indeed, but understand not; and see indeed, but perceive not. Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they, seeing with their eyes, and hearing with their ears, and understanding with their heart, return, and be healed.” (Isaiah 6:9–11)

Eretz Israel is our hope and our future is to identify with Zionism –

[Page 23]

our spiritual awakening; the realization of the Zionist ideal – our national healing.

The registrations for the Zionist Federation are taken place in the following locations:

After the Balfour Declaration the people became even more attached to the Zionist idea.

The First of May parade in Kishinev turned into a great Zionist demonstration of about 50 thousand people and left a great impression on the entire city. The joy was extraordinary. Dr. Pinchas Beltzen[2], the leader of the Youth organization – He–Haver (The Friend), recalled that he and his elder brothers Ben–Zion,

[Page 24]

Leib and Shimon were among the organizers of the Zionist demonstration. They assembled in the yard of the Yavneh Synagogue (where they always felt at home) together with the members of Tzeirei Zion, He–Haver and Maccabi (also established in the Yavneh courtyard) and waited for their turn to join the joyful demonstration together with all the political parties in the city. They started moving from the train station along Nikolaevsky Street toward the sport arena on Einzova, about a 5 km route.

Dr. Beltzen recalls:

“When the participants approached, Dr. Bernstein–Cohen stood on a chair at the edge of the sidewalk and the entire demonstration with flags and banners stopped next to him and he blessed the people in the name of the Zionist Federation and the Jewish people. Surrounded by the Jewish youth who desired to build a new life in our homeland stood Dr. Bernstein–Cohen a descendant of a Cohanim (priests) family who shed his Diaspora clothes with the yellow patches. He was proud to belong to the Jewish people, proud to desire an independent life just like the rest of the nations and called for justice for the oppressed people. He was proud of all the participating parties, but when the small group of the Bund participants with their large flag passed him, he hardly acknowledged them.

The Yavneh courtyard with the multitude of young people was like a citadel full of soldiers and when from both sides of the street groups of people carrying the blue and white national flag, it became clear that this is an immense Jewish demonstration. I can say that the “City of Killing” did not see and will not see a similar Jewish demonstration.”[3]

For the event, the young poet Eliyahu Meitus, wrote the poem “The Eagle of Yehudah” on the tune of the La Marseillaise, which was published by Tzeirei Zion under the title “The Flying Scroll”. The melody and the text filled the youth hearts at the demonstration with the desire for freedom, equality and national rebirth. The song became widely known in Russia and according to Meitus was translated into Russian and published in the Russian Zionist journal “He–Haver” as the Zionist Marseillaise.” It later became the hit song of the demonstration

[Page 25]

lead by M. Ussishkin and Professor Kloizner that took place in Odessa on 19 November, 1917 (3 December 1917) and marched to the British Consulate with the occasion of the Balfour Declaration.[4]

The “Dror” Publishing of Mendel Davidson in Soroca published a series of propaganda pamphlets in Russian: 1) Equality by D. Eizman; 2) On the Road by Dr. T. Herzl, 3) Zionism and Ethics by Zeev Jabotinsky, 4) On the Road to the Future by Leib B. Yaffe; 5) Selection of Revival Songs arranged by Itzchak Hitron (he was probably also the compiler) and a play for children in Hebrew entitle “Mishloah Manot” (The Gift of Food) by M. Ribesman. The pamphlets were widely distributed in Bessarabia and over the Dniester River and had a great influence on the Jewish street.

The huge national awakening among the Jews of Bessarabia raised important organizational issues about the elections for the Parliament, the local councils and the community organizations. Even if Dr. Bernstein–Cohen was very popular in Kishinev, the visit of Dr. Yehoshuah (Joshua) Buchmil, one of Herzl's faithful helpers raised problems for him.

The majority of the socialist parties, lead by the Bund intensified their resentment to the Zionist movement, claiming that if the equal rights are given to all nationalities in Russia, then the Jews do not need Palestine, therefore the Zionism in Russia should disappear from the scene. Although the thousands who came to hear Buchmil at the Circus arena were impressed from his lecture, they still demonstrated their strong support for the idea of national revival in the historical homeland.

Dr. Bernstein–Cohen was elected vice president of the Provisional Municipal Duma (the city council) and in August of the same year he was re–elected.

Footnotes:

The Seventh Congress of the Russian Zionist took place in Petersburg on 16–23 of Sivan 5674 (24–31 May 1917, or 6–13 June 1917, on the new calendar). The Congress was faithful to the popular aspiration, to the longing and to the will of the people to establish national institutions and representation among the Russian family of liberated nationalities.

Together they demonstrated the desire to return to Eretz Israel and rebuilt it.

[Page 26]

552 delegates participated at the Congress, among them 24 came from the war fronts. They were elected by the 140 thousand members from 340 electoral districts (680 settlements).[1]

The Congress received a warm welcome and its importance was reflected in the number of guests from across Russia – 500; from Petrograd (Petersburg) – 1000; the number of journalists who covered the event – 87. The delegates belonged to various factions such as: General Zionism –196; Tarbut – 50; Tzeirei Zion –112; He–Haver – 100; Mizrachi – 32; Activists – 26; Poalei–Zion –12, Beitar –528.[2]

Among the delegates from Bessarabia were Dr. Yakov Bernstein–Cohen, Leib Beltzen, Shlomo Berliand, Moshe Vanshelboim, Shmuel Yasky (Kishinev), M.Sh. Belotzerkovsky (Rezina), M.S. Vartikovsky (Khotin), Meir Staretz, I. Krasniansky (Akkerman), A.M. Frenkel (Brichani), Mendel Davidson and Chaim Shlomo Davidson (Soroca).[3]

Chaim Greenberg and Moshe Postan from Bessarabia participated at the Congress as delegates from the Ukraine. The leader of the Bessarabia delegation was Dr. Bernstein–Cohen, later elected president. Chaim Greenberg was elected to the Education Council, later located in Moscow.

The Second Congress of Tzeirei Zion, the Zionist youth organization, took place in Petersburg six days before the Congress (18 May 1917). Although providing great assistance to the Seventh Zionist Congress in Russia, the Tzeirei Zion was mainly divided into three ideological branches[4] that caused a lot of hurdles from the organizational point of view.

[Page 27]

These youngsters came straight from their Congress and installed their flag on the stage.[5]

The Union of the Zionist Students, “He–Haver” was close to the Tzeirei Zion and cooperated with them in many issues. Their function was to provide to the Zionist movement a force of intellectuals who will be able to lead the masses. Their other duty was to disseminate the central press published in Moscow and Petersburg.

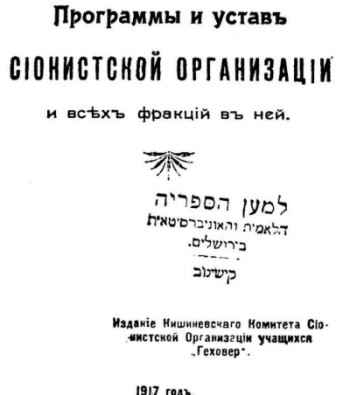

Immediately after the Congress, “He–Haver” published this pamphlet in Kishinev.

|

|

| Illustration No. 1: Programs and Charters

Zionist Organization and its Branches 1917 |

This pamphlet had the following sections: 1) Basel program; 2) Historical survey from the destruction of the First temple until today – 20 years from the First Zionist Congress to the 30 last years of activities in Eretz Israel; 3) Survey of all the Zionist divisions and the decisions taken at their Congresses; The decisions of the Seventh Zionist Congress in Petersburg; 5) Alexander Goldshtein's lecture on the need for a Referendum of the Jews of Russia regarding

[Page 28]

Eretz Israel and the significance of Eretz Israel to the lives of the Jewish people around the world.

The “He–Haver” movement had a great influence on the Jewish Street, but unfortunately when Bessarabia was annexed by Romania in the winter of 1918, it closed down together with all the Zionist activities for more than 2 years.

When the Zionist activities restarted, He–Haver amalgamated its activities with the Tzeirei Zion.

The Congress in Petrograd recognized the special importance of South Russia in the national movement and decided to designate this area for special privileges that will include also the Kherson area and Bessarabia.

On 28–31 August 1917 the region's First Congress took place in Odessa with the participation of 150 delegates and other guests. The participants heard many presentations about the plans and their implementation. Dr. Bernstein–Cohen, I. Skwirsky, M. Postan were elected to the regional Central Committee.

Footnotes:

As the elections to the Constituent Assembly scheduled for 11–13 November 1917 neared, the excitement and preparations grew on the Jewish street.

Dr. Bernstein–Cohen was the candidate on List no. 9 for the national election in Bessarabia. The list also included advocate Oscar Gruzenberg and Alexander Goldshtein (member of the Zionist Federation and the Rasvet editorial board), Shimon Dubnow, Israel Efroikin (member of the Central Council of the “Folks Partai” – People's Party) Friedel Lander (non–aligned, senior official for Jewish affairs for the Commissar of the Police of the Provisional Government of Galicia and Bucovina), Meir Kreinin (member of the Central Committee of the Folks Partai (People's Party), Eliezer Kaplan (member of the Central Committee of the Zionist Federation and the Chairman of Tzeirei Zion and Moshe Aharon Treinin (Folks Partai and publisher of Noviy Puti (The New Road).

Two lists among the 17 lists competed for the Jewish vote: List no. 4 of the Socialist Democrats in cooperation with the Bund lead by Grisha Luria, Nadejda Konigshatz–Greenfeld and Benyamin Greenfeld (Bund) and List 17 of the Poalei Zion led by Shlomo Goldman and Nachum Rafalkis (Nir).

[Page 29]

|

|

| Illustration No. 2: Evreyskiy Golos (Kol Israel –The Israel Voice) – Pre election Journal of the National Jewish Council for the All Russian Election to the Constituent Assembly and candidates lists from Bessarabia. Autumn, 1917 |

[Page 30]

We read in the memoirs of Dr. Bernstein–Cohen:[2]

All the land owners, the nobility and all the supporters of the old regime supported the candidacy of Bishop Serafim, for the Old Guard and the nobleman Chichigov from the Tsar's court. All the members of the “Russian People Union” from the “Black Century” came to the neighborhood to gather votes. The Jewish public proposed my candidacy even if I, personally, was against this modernized All Russian Constituent Assembly. First, I knew very well the history of Russia and did not expect anything good coming out of it; second, I followed the Jewish press and the Bolshevik propaganda and even if I did not think that they will immediately resort to violence, I was sure that it's bound to happen sometimes soon. I decided not to try for the Assembly, although in my heart I wanted to defeat Serafim and the “Black Century” and I accepted.

I was elected not only by the Jewish vote, but also by the Moldavian Christians from the same neighborhood where my patients lived. Serafim was angry, but all the priests and the monks were happy to see his downfall and gave me the victory blessing.

I found reasons to distrust the Assembly and in order to check the “vibes” two people went to Petrograd, the former mayor, Levinsky and, I think, the adviser of the new Duma, Godunov. They returned in a hurry and told us that the Constituent Assembly will be soon dismantled. Only fate saved me from this experience. I was well aware of the situation in Petersburg and I knew the ideology and the propaganda tactics of the Bolsheviks in those days.

The lists of the “National Jewish Council” were represented in 12 districts and received 700 thousand votes – more that 75% of all the Jewish voters. The National Jewish Council received 7 mandates. That was the people's response to those who pretended to speak in the name of the “masses” but whose priorities were their status and not the national problem.

The Jewish elected representatives of the National Council were: Julius Brodtzkus (Minsk), Yakov Bernstein–Cohen (Bessarabia), Alexander Goldshtein (Podolia), Oscar Gruzenberg (Kherson), Vladimir Tiomkin (Kherson), Rabbi Yakov Mazah (Mogilev) and Moshe Nachman Sirkis (Kiev). Only Gruzenberg was considered a non–Zionist, but he signed on the Zionist political platform.[3]

[Page 31]

They formed the Jewish National Faction of the Constituent Assembly and were guided by the decisions of the All–Russian Jewish Congress.

The Constituent Assembly opened as scheduled on 6 January 1918, about six weeks after the October Revolution under the name of VTsIk[4] (All–Russian Central Executive Committee). The next day the Assembly was dismantled by the army situated at the Tauride Palace[5].

Footnotes:

The preparation for the elections for the All–Russian Jewish Congress coincided with the preparation for the elections to the Constituent Assembly that were scheduled for 5–9 October 1917, about a month before the elections for the Constituent Assembly. The elections were postponed a few times (3–6 December to 7–9 January to 21–23 January 1918) and the tension remained high.

One of the most important election issues that preoccupied the Jews of Bessarabia was the question of the national, cultural and religious autonomy for the Jewish minority. This issue was at the top of the platform for the elections for the All–Russian Constituent Assembly.

The Jewish Congress (or the “conclave” in Russian), represented the Jewish population of 5 million people[1] a fact unheard of in the dark ages of the Tsarist regime persecutions. It gave the impression that the promised negotiations for human rights would become a reality and here, on the liberated Russian soil, it will bring a huge turning point in the Jewish Life.

The many political parties, meetings and programs, endless stormy debates

[Page 32]

preoccupied the Jews everywhere into looking for solutions, programs and especially wanting to win. The Council of the Union of Jewish “Conclave” published a pamphlet for all the Jews of Russia with the 10 lists of candidates. The propaganda grew, the candidates went from house to house to campaign, votes were gathered and the expectations grew while waiting for the election results. Then, all of a sudden the October Revolution took place and this complicated the matters further. The Jewish leadership and the Jewish voters in Russia started to panic – what will happen with the golden dreams? Is everything finished?

It became clear that the elections will not take place in all 46 districts, that it was impossible to reach all the voters and that their numbers were a lot smaller. The situation aggravated when on 16 January 1918 the Romanian army occupied Bessarabia and annexed it to Romania.

Footnote:

When the new socialist regime started to organize after the first revolution, the February revolution, it became clear that among the Moldavian intellectuals there was a group that opposed the revolution and that undermined the new regime in Bessarabia. This group did not want to belong to Russia or to the Ukraine, but desired to establish an independent Moldavian community lead by a People's Council (Sfatul Țarii) which will form a government. They tried to convince the Zionist Federation to join in and offered 40 mandates in the government compared with 1 mandate for the Bund (B. Greenfeld from the Bund won a seat in the government and was minister of finance[1]).

It was clear that the conspirators wanted to create an autonomous republic with the Moldavian army stationed in Odessa and establish a strong tie to the “mother homeland” – Romania, but the Zionist Federation refused to join. In the mean time, there were strong disagreements[2] between Sfatul Tarii and the Jewish representatives regarding the national make–up of the Council. According to the new statistics

[Page 32a]

|

|

Kishinev, Iyar 5680/1920 1.Unknown, 2.Tz. Atlis, 3. Unknown, 4. G. Halperin, 5. M. Shorer, 6. Unknown, 7. M. Hershkovich, 8. Levit, 9. A. Kritzman, 10. Z. Pitkis, 11. Unknown, 12. Advocate I. Feidel, 13. N. Averbuch, 14–18. Unknown, 19. Sh. Yasky, 20. H. Goldshtein, 21. I. Lerner (Laron), 22. I. Schwartz, 23. Sapojnik, 24. B”Z. Mordkovich, 25. A. Chacham, 26. Advocate R. Shreibman (Shari), 27. Dr. M. Kolker, 28. M. Finkelshtein, 29. Unknown, 30. D. Veinshtein, 31. Unknown, 32. I.R. Marmelshtein, 33. Ab. Weisman, 34–35. Unknown, 36. I. Cohen, 37–40. Unknown, 41. I. Pagis, 42. I. Shreibman (Shari), 43. Tz. Shorer, 44. Sh. Keinarskaya, 45. P. Bergman–Greenberg, 46. Unknown, 47. B. Gitchku, 48. M. Greenberg, 49. A. Feinbrun, 50. I. Berger, 51. I. Chitron, 52. Sh. Greenberg, 53. L. Kleiner, 54. L. Beltzen, 55. A. Polikman, 56. M. Masis, 57. M. Shichman, 58. D. Vertchaim, 59. I. Blank, 60. Eliyahu Meitus, 61. Advocate M. Shechter (Misha), 62. Dr. Bernstein–Cohen, 63. M. Gottlieb, 64. Unknown, 65. I. Shochet, 66. Dr. I. Bilostrotzky, 67. H. Postman, 68. L. Trachtemberg, 69. Advocate M. Landau, 70–71. Unknown, 72. Sh. Keinarsky, 73. Yagolnitzer, 74. Kighel. 75. Leivant, 76. M. Tzimring, 77. A.Z. Shochetman, 78. Sh. Feldman, 79. I. Pinchevsky, 80. I.K. Rosenberg, 81–82. Unknown, 83. P. Margalit, 84. Unknown, 85. Yasinovsky, 86. Staretz, 87. I. Beigleman, 88. Sh. Nathanzon, 89. Rabinovich, 90–94. Unknown, 95. M. Dorfman, 96. Unknown, 97. M. Rotkov, 98. I. Danovich, 99. Unknown, 100. Karakoshansky, 101. G. Cohen, 102. Ab. Milgrom, 103, Unknown, 104. Veinshtein, 105. M. Tolmatch, 106. I. Greenberg, 107. H.Tz. Prizant, 108. M. Rabinovich, 109. I. Berman, 110. Ab. Dovubi, 111. Z. Shechter, 112. Halperin, 113. Unknown, 114. M. Nitoker (Yasky), 115–121. Unknown, 122. Z. Tomazsky, 123. Eidelman, 124. Unknown, 125. Z. Toriyansky, 126. Tz. Cohen, 127. Unknown, 128. I. Appleboim, 130. Rabbi Z. Rozenfeld, 131. Rabbi Ab. Polinkovsky, 132. Rabbi M. Shochetman, 133. Unknown, 134. I. Yashan, 135. Unknown, 136. P. Mutchnik, 137. Mrs. Mutchnik, 138–139. Unknown, 140. B”Z. Porer, 141. Unknown, 142. B–Z. Beltzen, 143. Unknown, 144. Sh. Beltzen |

[Page 32b]

|

|

Jassy (Iași), Elul, 5680/August 1920 1.R. Shreiber (Shari), 2. Ab. Chacham, 3. Bronfeld (Yardeni), 4. Kazak–Averbuch, 5. L. Belzen, 6. Lerner (Laron), 7. B–Z. Mordkovich, 8. A.Z. Shochetman (Eligur), 9. Advocate M. Landau, 10. M. Postan, 11. B. Fuchs, 12. Karakoshansky, 13. M. Shtern, 14. A. Weisberg, 15. I. Shreibman (Shari), 16. Yasky, 17. Ab. Weisman, 18. Advocate I. Dankner, 19. L. Fisher, 20. Unknown, 21. I. Danovich, 22. Riokman–Vaislavsky, 23. D. Vertheim, 24. H. Verthaim, 25. Gorpel, 26. Mrs. Rozenthal (Pikhandler), 27. Kroll, 28. I. Dobinovsky, 29. M. Abeles (Landau), 30. M. Nitoker (Yasky), 31. Unknown, 32. Geler, 33. Greenberg, 34. Ek. Greenberg. 35. Sh. Beltzen, 36. Unknown, 37. Strulovich, 38. Unknown, 39. Dr. V. Abeles, 40 –41. Unknown, 42. Karni, 43. Advocate N. Davidovich, 44–46 Unknown, 47. Bograd, 48. M. Flum, 49. P. Friedman, 50. I. Shteinhouse (Amitzur), 51. Advocate I. Kushnir, 52. I. Staretz, 53–53. Unknown, 55. Tz. Peled, 56 T. Peled, 57. Ag. Abeles (Kochavi), 58. Unknown, 59. I. Diokman, (Bar–Shaul), 60. M. Heshcovich, 61 I. Cohen. |

|

|

– Second and Third day of Intermediate days of Sukkot 5681 (1921) (From the Michael Amitz collection) From bottom to top: Row 1: From right to left sitting: B'Z. Malchzon, B. Shiler, Unknown, I. Feldsher, H. Gross, D. Zatzman (Malchi), I. Zemura, H. Yadlin, M. Shteinhouse (Amitzur), A. Yaffe. Row 2: In the middle sitting: M. Vartikovsky, I. Appleboim, A. Z. Melamud, M. Gleizer, N. Leiderman, I. Shteinhouse (Amitzur), Sh. Leivant, M. Veinshtock, Rabbi M. Givolder, Ab. Milgrom, H. Gross (Roiz?) Row 3: Standing: L. Bary ? B. Weissadler, Ab. Weisman, Reinis, M. Vizeltir, N. Weisman, A. Sheinhauser, Sh. Weisberg, I. Barafael (the Eastern region representative), D. Lerner, I. Cherkis. Last row: P. Greenberg, I. Kochat |

[Page 33]

the Moldavians represented 49% and the Jews 13% of the general population. The Moldavians received 105 mandates of the 150 and the Jews got only 10. The Bund, that was close to the monarchy and even actively participated in the propaganda among the peasants, proposed to “compromise” for a total of 14 mandates for the Jews so they can get 10.

Dr. Bernstein–Cohen refused in the name of all Jewish parties in Bessarabia and in a memorandum to the leadership proposed to have the 19 mandates proportionate to the Jewish people in the population – 7 mandates to the seven districts and 12 to the Kishinev district. These mandates will be distributed equally to all the parties: the Zionists, the Bund, the Orthodox, and the People's Party (Folks Partai).

The leadership of the “Sfatul Țarii” did not agree to this proposal until it was decided for them by the Romanian Army occupation.

1918: The October Revolution is raging; the Bolshevik Regime, the military communism seizes power, the civil war and the last breath of life of the various parties in Russia, soldiers, “Whites”, “Reds” Independents, Poles and Germans fighting each other, victors and losers, ups and downs; the industry is dead, the transportation is shuttered, the economic life is ruined – shortages of food and clothing, raising prices, famine and diseases, typhus epidemic, gangs fighting in the cities, gangs attacking the smaller settlements.

The Ukraine is especially hit hard: roads are dangerous, various gangs – Petliura's gangs, Grigoryev's gangs, Tiutiunnik and the Green gangs (because they hid in the forests), Batko–Makhno gang terrorized the Jewish settlements, robbing, killing, massacring and demanding ransom called “the contribution.”

Bessarabia located between the Dniester, Prut and the Danube Rivers was less harmed than the Ukraine, the neighbour. Despite that, Bessarabia suffered from the retreating armies that were returning home without any plan or order and, because there was no supervision, they were free to raid and devastate.

The worst of the damage was done by the Circassian cavalrymen. They occupied the abandoned farms and during the night they attacked the Jewish villages and the rich peasants. In Edinetz, Faleshti, Bolgrad, Kahul and Killiya there were assaults that lasted 2–3 days (28–30 November 1917)[3]

[Page 34]

In some locations, the assailants were met by armed resistance by the locals who just returned from the front and still had weapons from the dismantled and retreating armies.

The nationalistic Moldavians are pressing for the return to “Mother Romania” from which they were cut off in 1812.[4] Even the Russian, especially the rich landowners and owners of properties, mostly the city dwellers, do not want to have the same fate as their brothers east of the Dniester who are now under the rule of the Bolsheviks.

“Sfatul Țarii” immediately urged the Romanian government to liberate Kishinev from the “Council of Deputies of Soldiers, Workers and Peasants” and to save the lifes and properties of the citizens. The Romanian Army entered Kishinev on 15 January 1918 and an Ultimatum was given to the city “Duma” (Council) to have the Bolsheviks and the Council of Deputies of Soldiers, Workers and Peasants depart from the city the next day. The soldiers were scared to confront the Romanian Army therefore the City Duma surrendered to the ultimatum. (Note: The historic meeting of the city council was conducted by Dr. Bernstein–Cohen, the Deputy Mayor, because the Mayor fled the city).

The Romanian occupiers imposed harsh rules of siege. The ones who opposed the rule was arrested and punished to be flogged on the naked body publically. Many of these people became disabled for life from the beating. On top of that, the soldiers and the officers were openly pillaging the city.

The bloodbath was extremely brutal in Eidinitz (Khotin District) where 3 Jews were publicly executed. They were part of a delegation of 16 Jews and 6 Christians who came to see the Commander of the city on the Seventh day of Passover dressed in holiday clothing. A few day earlier 2 peasants from a neighbouring village were executed in the middle of the city[5].

News of the cruelty and rampages, despite the peaceful acceptance by the local population, reached beyond the Bessarabia borders. The Jewish community in Petersburg declared Thursday, the 23 May 1918

[Page 35]

a day of national mourning in memory of the victims of the disturbances in Bessarabia. In Belorussia and in the Ukraine all public institutions were closed and prayers were said in the synagogues.

The community in Bessarabia did not recover for a long time and the parties and organizations did not reconcile with the occupation authorities. There were protests and petitions were signed and illegally sent abroad. Dr. Bernstein–Cohen was among the leaders who actively laboured against the atrocities of the new occupation. Many asked the new government of the Soviet Union to come and rescue Bessarabia from the occupation and return it to the Russian Motherland.

The truth was that the 100 year border that separated the Romania from Russia, the Prut River, now moved to the Dniester River. Now the Dniester became the border of two foes with two hostile regimes.

Footnotes:

The occupation of Bessarabia by the Romanian Army (January–March 1918) was accompanied by terrorism against the local population. This population with a higher cultural and education level and a developed public life during the Tsarist regime was deeply shaken by the unruly new occupation. The Jewish population was especially affected by the “Romanization” and the need to adapt to the new actuality; and because, the Jewish community of Bessarabia had strong ties with Russia and its culture, the divide caused great grief.

Soon the Jews of Bessarabia became convinced that the occupation and the new Dniester River border had positive outcomes:

The Jewish Community at that time numbered about 250.000 people

[Page 36]

(according to the official census – 267 thousand people) and was mostly rooted in agriculture. The agricultural settlements that started at the beginning of the 19th Century were the pride of Bessarabia. From these settlements people left to settle in the Argentine Pampa and in Eretz Israel.

This inspired the people to believe in Zionism and the natural and simple connection to the land of Zion.

Bessarabia Jewry did not produce great journalist, writers, philosophers and politicians. The Jews of Bessarabia were hard working people, quiet, respectful and modest and were totally dependent on the Odessa Council and central organizations which were the spiritual centres of South Russia.

The Hasidism that had its deep roots in Bessarabia was also dependent on the Hasidic courts over the borders. The only contributions of Bessarabia to Hasidism were her sad melodies and the famous “volachel” (a kind of a dance).

Bessarabia was rich in vineyards and famous for its wines. The Jews knew how to tell the wines and were drinking responsively, being careful not to get drunk, mostly worrying about their livelihood. The drinking was accompanied by music and the “volachel” dance at all occasions; weddings, holidays and shabat, a memorial for a Rabbi. Even the prayers had a special agricultural significance: The Prayer for Rain, or the Prayer for Dew and others. They brought with them to Eretz Israel the music inspired from the melodies of the Moldavian shepherds that reminded them of the earth and the farms.

When the Jews of Bessarabia were separated from their brothers in Russia and became isolated, they were forced to confront with the serious problems and they had to find a way to stand up for themselves. It helped them find their own cultural, spiritual and public image and discover their natural spiritual power that was asleep until then.

[Page 37]

The painter D. Ben–Menachem from Bucharest, with the help from Tzeirei Zion, painted in 1919 a map of the “Republic of Eretz Israel” with the portrait of Judge Louis Brandeis, the president of the Hebrew Republic.[1]

The Zionists also prepared a model of the government of the Jewish State with Dr. Chaim Weizmann as Prime Minister, Max Nordau, Chairman of the Parliament, Nachum Sokolow, Foreign Minister, Rabbi Yakov Nemirover, Education Minister, etc.[2]

This new community had to struggle to become independent from “her older sister” and strengthen the National movement after the Balfour Declaration. Slowly, it built the central foundation of the Zionist movement and all its branches: education and culture, training of pioneers, immigration, fund raising for the national funds.

All of a sudden the national sentiments woke up and intensified even among the big city dwellers that were indifferent to the national idea and started assimilating. With the separation from Mother Russia and with the forced Romanization by the new “step mother,” the process of assimilation stopped. Its “Judaisation” replaced assimilation and after that it evolved to the Hebrew school, the demanded support for its rights.

The activists from the large cities and from the settlements responded to the new task and dedicated themselves to new roles in areas of national cultural and public work even outside their home base. The Hebrew teachers were especially active as public pioneers. Volunteering became widespread and they visited the small towns in order to establish ties and strengthen the basic activities.

The pioneers from Russia among them many teachers and Tarbut activists who stopped in Bessarabia on their way to Eretz Israel provided extensive support. They were the ones who helped found the movement organizations and gave wings to the courageous activities.

Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

The Jews in Bessarabia

The Jews in Bessarabia

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 09 Aug 2020 by JH