Offerings of Thanks

Chaim Bronshtain

It is incumbent upon me to thank all the people of my city who acted and assisted in the preparation of this anthology. I cannot name all of them, but I offer special thanks.

A faithful and devoted partner, who acted indefatigably for the perpetuation of the memory of the town, our shtetl, Skalat, in this anthology was, for me my comrade in work and mindset, Ze'ev Reuveni. A dear man, a native of our city, Chaim Dlugacz, was of great assistance to us with his professional knowledge in the field of printing. He aided greatly in the external layout of this anthology.

Likewise, blessings are due the workers of the OT Press for their devotion and their patience, and for their beautiful work.

This anthology is modest in its scope and does not at all pretend to serve as an inclusive and comprehensive expression of how the Holocaust affected the Jews of Skalat. That would require a massive book.

There exists great doubt whether such a book will ever be written. Those who had the ability to shoulder this difficult task perished in the Shoah. The events were cruel, and did not leave any opportunities to create testimonies in writing. Memories were left behind with those who perished. Only pain remains.

And even if many years have passed since then, our pain continues to echo in space. It is eternal pain, and will last until our departure from the face of the earth.

May these pages, in which the cry of our pain is contained, be a memorial candle for all the residents of our town, Skalat: fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters, relatives and friends, who watered the ground of Skalat, Belzec and all the land of Poland with their blood.

Poland, do not cover their blood!

The Editor, Chaim Bronshtain 1971

[Page 8]

|

|

Abraham Shlonsky

| With the assent of my eyes which behold the bereavement and heaped cries upon my bowed heart, With the blessing of my compassion which taught me to forgive until days came which prohibited me from forgiving, I have made the vow to remember everything, to remember – and not to forget a thing. |

20 Teveth 5728 (1-21-68)In Honor of

Mr. Ze'ev Reuveni

Principal of the Krol SchoolDear Mr. Reuveni,

I am unfortunately unable to be with you at the ceremony memorializing the Skalat community which will take place this coming Tuesday, 22 Teveth, this week. I will therefore suffice with a few words, in writing.

The project of the memorializing of the communities is, in my eyes, one of the important projects that enable the creation of a monument to a Jewry, which was destroyed in the years of the Holocaust. Through the bond with one of the communities that was exterminated, it is possible to recognize a point of original Jewish life. Here is a basis for testifying to an entire center of Jewish life to which Skalat belonged, where there was both a secular life and the milieu of Sabbath and Festivals. Here one can recognize the educational institutions, culture and the life of spiritual creativity. One can understand the worry about existence and livelihood. We discover and learn about the distinguished personalities and the common folk, about the creators and their creations, and about those who drew on inspirational sources and devoted so much of their time to Torah study.

All of these existed and no longer exist. But tomorrow cannot exist without yesterday.

Through memorializing the communities, through the attachment of a school to a specific community, this one or another – all of us can recognize the life that was, and the good and the beautiful which our ancestors bequeathed to us, that we may establish our home in Israel.

It is my trust that all of you who now memorialize the Skalat community, will know how to persist in the study of the life which existed in it, and thus will provide a monument to the preservation of its memory.

Respectfully,

Y. Frischman

General Vice-Director

By Dr. Baruch Ben Yehudah

I will admit it and not be ashamed. When they started to talk about “The Project of Memorializing the Communities” by schoolchildren, I hesitated about the educational power of the idea. Insofar as the thought occurred to me, I am certain that consciousness of the Holocaust needs to become a foundation of first rank in the education of our generations. I cast doubt on this path out of lack of faith in the possibility of converting forms of life and social values, which are only in the memories of the teachers alone, into exciting, moving and interesting educational material.

And then, I had occasion to convene delegations from all the schools in the country in the National Convention Center Auditorium in Jerusalem for summarizing the year of action for the project. Hundreds and hundreds of children filled the great auditorium. Mr. Gideon Hausner spoke to them, and the children read and carried out different performances. I directed my eyes not to the stages but behind me, to the children's benches. What silence, what concern on every face, what cooperation with what was being said and being done on stage! It seemed to me the children heard the rustling of the wings of the Divine Presence hovering between the rows and the weeping of the Shekhinah...

And something moved in my heart. And then I was invited by my friend, Mr. Ze'ev Reuveni, principal of the school named for Krol, in Petach-Tikvah, to be present at the ceremony for the adoption of his community, the Skalat community, that was in Galicia, by the children of his school. And, again, that impression returned - a true experience of children, a precious and intensive educational time, a pure-hearted activity on the part of the students, and cooperation arousing a bond between the principal, the teachers and the students.

These two things removed any hesitation from my heart. I had erred in that I had considered the children alone, and had not added to the calculation the part of the educators. But if the latter brings to their students a chapter of Truth, which is recognizable in every movement of their lips, in every movement of their eyes, and in every slight hoarseness in their throats, which comes in lieu of restrained tears – there is nothing greater than the power of truth in education.

Even today, Ze'ev Reuveni feels the pain of his community, which was destroyed. So too did Gideon Hausner, who, in the opening speech in the Eichmann Trial, riveted the entire nation of Israel and the entire world with the feeling that the six million souls were hovering over our world and demanding justice and retribution to the evil-doer. He too converted the truth, which was in his heart, into an education moment.

May your hands be strengthened, my dear friend, Reuveni. And may the hands of all the educators be strengthened – and at the head, Mr. Dov Alloni – for they succeeded with the truth, which was in their hearts, to attach myriads of children to the chain of the life of the nation in its generations.

By Chaim Bronshtain

Of the historiography of the Jewish town, the Shtetl in Eastern Europe is the weakest link in Holocaust research. Small towns left behind them few traces in books or chronicles, are almost not mentioned, and the little bit remaining leaves behind it many gaps.

One who attempts to uncover the history of a small town is in the category of a person searching in expanses of desert sands for a lost pin. History, as it were, passed by these small neglected towns, and left them at the sides of the road. Despite the fact that the economic, religious and social activity in the small town was suffused with much tension, no mention was left of this daily existence.

The historiographic poverty in the area of the history of the Jewish small town is striking, and this poverty consigns the fate of the small town to be forgotten, to be entirely erased. Towns in which Jews lived for hundreds of years would not be remembered in coming generations.

|

The Holocaust issued a total verdict against the Jewish town. With the kind help of the people of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, and particularly that of Mr. Yitzchak Lan, we succeeded in discovering traces of the history of the town Skalat in several sources:

- Encyklopedia Powszechna T. 23. Rok 1866

- Slownik Geograficzny Krolewstwa Polskiego T. 10. Rok 1889

[Page 13]

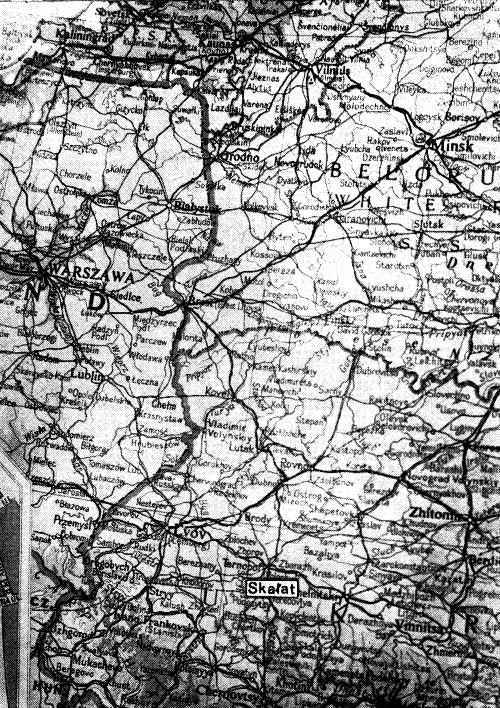

According to the Encyklopedia Powszechna, from 1866, Skalat was located, in ancient generations, in the Russian Kingdom. In the second half of the 19th century, Skalat was found in the territory of Galicia, in the vicinity of the Gnula River. An ancient fortress, which was built in the 16th century for defensive purposes, enhanced the city. In this period, there were three thousand residents in Skalat.

Slownik Geograficzny from 1889 contains more details about the town. At the end of the 19th century, Skalat is the Miasto Powiatove, the county town in East Galicia, southeast of Tarnopol. In 1870, there were 4,592 residents, 2,552 of them Jewish.

According to Korftinitski, in Geography of Galicia from 1786, it is clear that Skalat was the inheritance of the Tarlov Family of Shaknovitz, from which the land of Skalat passed to the Princes of the House of Poniatowski. They sold it, around 1869, to a Jew named Ziskind Rosenstock.

Rosenstock was a famous Jew in his generation, the holder of the title Baron. One of his descendants, Alexander, converted to Christianity. He sold the land of Skalat, which Joseph Tenenbaum bought, specifically the land of Novosilka in 1920.

The source of the following information is from the population census held in Poland in 1921. According to this census, there were 5,957 residents in Skalat, 2,919 of them Jews.

According to the Bletter Far Geschichte for the Jewish Historical Institute in Poland, from 1953, there were 4,600 Jews in Skalat in 1941. In 1942, because of the forced move of Jews from the environs, the Jewish population increased to 8,500.

According to Abraham Weissbrod, in his book, Death of a Shtetl, of all the Jews of Skalat, there remained only 160 persons after the war.

By Chaim Bronshtain

|

|

More than a half jubilee of years has passed since I left the city of my birth, Skalat, for the last time. The city let me drink from its golden cup, but also one from the goblet of poison – in its last days.

A person drinks only once from the days of childhood. It is from Skalat's streets, its alleys, and its landscapes, that this city took form. And even if many years have passed since you boarded the train that carried you far, far from it, and in your heart there is a severe curse against the city and its inhabitants, you are unable to be reminded of it without yearnings and pain. You are unable to free yourself of the feeling that this city is part of your being, and you carry it inside you wherever you turn.

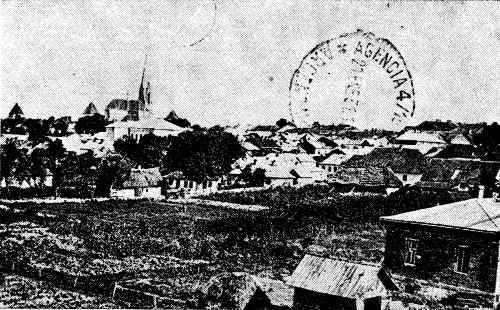

Skalat is a small city. Its streets are few and its alleys are numerous. In my eyes, there is nothing more beautiful than Skalat, in the hot days of summer, in the days of idleness from study. We ran around in its streets and were caught up in the wagons of the farmers and peasants loaded with the sheaves of the field. And even when the whip whistled, the sweetness of the experience did not dissipate.

Between the walls of the cramped Cheder, we sat learning around the table, riveted to the square letters, and absorbing the words of the Melammed, the Jewish Primary Teacher. And he, the elderly Melammed, opened up before us the gates and doorways to hidden worlds, filling all the chambers of our heart, to feel the heavenly Jerusalem and the earthly Jerusalem, the Western Wall and Rachel's Tomb, Hebron and Bethlehem. The entire Land of Israel is here, dwelling among the walls of the Cheder, and you stroll in its expanses. The rebukes of the rabbi, our teacher, the sharp pinch of his yellowed thumb, did not have the power to make us forget Rachel's tears, the ultimate Matriarch, who refused to be comforted.

In the dark winter nights, in the fierce snowstorms, with the small city lantern in your hand, you make your way from the Cheder. It's cold outside but warm inside. You walk, erect and proud of everything around you, with mercy in your heart toward the vanities of the Gentiles who did not know the Truth of the Torah. You feel no hatred but, rather, sorrow for the Gentiles.

There passing before your eyes are the multitudes of the House of Israel who inhabit both its lofty and its small houses. Here they are, the wealthy of the town, passing by in their splendid coaches, who arouse in you a bit of envy, and the masses running about in its markets and its alleys in order to find a crust of bread. Jews adorned with beards and kapotes, kaftans. Jews with cut–off sidelocks wearing hats on their heads, slightly embarrassed for having ‘broken down the fence,’ that is, having deviated from Orthodox norms, but their trust in God still with them. On Shabbat nights, and on the eve of every festival, you will find them in the synagogues. Their faces shine, serious, gathered into themselves, with their ears attentive to the distant song of the stars.

And suddenly everything was silenced. A great darkness prevailed over the world and covered the eye of the Sun.

In July 1941, the Red Army retreated, day and night, on the main roads leading eastward. Tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands are fleeing in panic, some by vehicle and some on foot. Hungry, torn and wounded, they gallop eastward. The iron skies above keep silent. But the dust of burning rises in the air, its odor sharp and threatening.

Then everything was silenced. The last of the Russian soldiers left the city. At the twilight hour, the silence of a cemetery surrounds you. It is like the day of the creation of the world, and you do not know what to expect.

At midnight, Friday night, at the beginning of the month of July, automobile horns and noise of wheels announced the entry of the German Army to the inhabitants of the city who were enclosed in their homes, inclining their ears with worry and anticipation. And in the morning, after a night of watchfulness, you saw them up close, proud, erect, sitting in their vehicles on their way eastward. Their uniforms pressed. Their boots sparkling, and their weapons polished. Thus the victorious conquerors of the world always appeared, in all generations.

And moreover, on that day, in the afternoon hours, the first Jews were taken out of their houses and executed in gruesome ways. Some by water and some by fire, and yet the heart refused to admit that something awful had occurred, that we were standing at the entrance of a depth whose end we could not foresee.

A new day, Sunday, hundreds of Jews – men, youths and elders – were taken out of their houses, at the sounds of laughter of crowds of Poles and Ukrainians, residents of the city. They did not return again to their homes. In cellars of old fortresses, at the edge of the city, they were all executed, young and old.

And still it seemed that this was an accident, at the hands of malicious people. It was not possible. Until days came which threatened forgetfulness. Famine, forced labor, disgrace and humiliation, taxes which sucked the marrow out of bones, wandering with shadows past the boundaries of the Ghetto – what are all these compared to the days of terrors which came afterward.

The summer of 1942. The Judenrat was assigned to supply a quota of men to the Germans to be executed. Even Satan was not capable of inventing a malicious trick more terrifying than that. The day was appointed. The hour was set. And you, O man, arise and select who will live and who will die. The lot fell upon the elders of the city. Grandfathers and grandmothers were separated from their children, their grandchildren, and their great–grandchildren, and were forced out onto the road. They were gathered in the interior of the synagogue. From there they would be taken out in trucks to their last destination. They were na´ve, believing that in death they would be saving their offspring and the entire remainder of the community.

But they were mistaken. A few months after the city was emptied of its elders, the axe was waved anew. At dawn, the ghetto was surrounded. This time all of them went, young and old, fathers and mothers, children and infants. The end of the world arrived. Doors were forced open. Windowpanes were shattered. There were roars of human beasts who were bursting in like preying wolves to the apartments of people sunken in sleep, broken vessels wherever you would look, people dressing hurriedly, mute, frozen, shocked to the point of silence. At the distance of a step, you seek a father, a mother, a brother, a sister, pushed and exiting. You want to cry, but you know if you desire to live, you disappear into the midst of the ground and pretend not to notice.

And once the storm has passed, and you have remained alive, you learn that over three thousand Jews have been removed from here in the course of two days, and there was but a step between you and them. One Aktion follows another. And always someone remains, and always many, many disappear, until half way into 1943, there is no more ghetto. There are no more Jews. There are no more Aktions….

Remnants of the community still struggle for their lives in a camp, which is in the vicinity. Every morning they go out to the stone quarries, which are outside the city. Again, death is upon their faces. They know that their fate is sealed. A few remain. Their families have perished, and even their days are numbered.

Indeed their days were numbered. Speedily, even this small remnant was led to pre–dug, deep pits that were previously prepared.

Life was over!

And when the day came that the city was liberated, and the last remnants were gathered to it – and they were very few – they stood mute, suppressing their grief inside, and were not even able to cry. The sound of tears was dried up.

They still managed to visit the graves of their loved ones in the expanse of the field. Wherever you tread, you hear the cry of the tortured, and you know that you will no longer find rest for your soul.

Not many days have passed, and the entire remnant gathered and then left here, the giant cemetery, whose name is Skalat.

Twenty–five years have passed since I left here. Somewhere in the world, there still dwell loving people in its houses, streets, alleys, living, breathing. Surely, they sleep their sleep at night, and do not shudder when the spirits of the dead knock on their doors with their fists…

And still I think, while awake and in dreams, of the city of my childhood. And I know that the following words were said of me, when the poet wrote:

| AND IF THE ANGEL SHOULD ASK:

My son, where is your soul? |

Remarks at the Ceremony of the Perpetuation of the Community of Skalat, at the Jacob Krol School in Petach–Tikvah on 22, Teveth 5728

|

|

By Shlomo Ansky

| This narrative is taken from Shlomo Ansky's book, The Destruction of Galicia (translated by Shmuel Zitron). Ansky, also the author of The Dybbuk, visited Jewish settlements in the region during the years of the First World War, and organized aid to war victims on the front. His impressions of the desolation, which the war wrought on Eastern European Jewry, are described in his book. Here is a segment, which relates his impressions of his visit to Skalat. |

| Chaim Bronshtain |

At a late night hour, I came to Skalat. At the only inn located in the town, there was one room, but the cold inside was as great as outside.

I awoke from my sleep just when dawn came up. When I withdrew my head from the hairy blankets with which I was covered, I saw that there was an old woman in the room standing by the stove. When she saw that I had awakened, she gestured with her hand as if calming me, and she said, “Sleep, sleep, I'll wait!”

“What's up with you?” I asked her with astonishment. “I have something to tell you,” she says. “People will come to you from the entire city and you will not have free time, so I came to wait until you awoke from your sleep. I will sit here in this lodging–place”.

It was already known who and what I am, and the woman had come early with her request. Even though she gave me permission to sleep longer, she nevertheless began speaking and narrating. She was one of those who had been exiled from Podvolochisk. She had been a prosperous housewife. Now she and her children were experiencing awful days. The owner of the lodging house was a relative and had allowed her a corner of the house. In return for that, she and her children had to perform every kind of crushing labor. And not only that, but she had to flatter the mistress of the house and offer her ingratiating talk. Far be it for the woman to complain to her about how much she and her children suffered from hunger and cold for the eighteen months she had been living here in Skalat in the house of her relative! Her children, two girls who had reached puberty – were both beautiful and talented. They spent the entire year in the house, lacking shoes. Now, they had received eighteen rubles for shoes from the Committee. But what can one do with eighteen rubles? Besides there was also a need for dresses as well.

The woman already knew that I had brought a bundle of blankets, and now she was asking that I give the blankets to her and her daughters.

While her words were still on her tongue, another woman came in dressed in prosperous clothing, with a gold watch protruding from her pocket. Right away, she says that this watch is the only thing left of her former wealth. A young man, a member of the Local Aid Committee, had entered the room with her. The woman had one request: her only son, a youth of distinguished talents, had completed the school curriculum in five classes at the gymnasium. For the two years since, he has been idle. So she has requested that the Committee hire him a teacher to prepare him for the university.

The committeeman interrupts her speech and says, “Your son is able to acquire teaching preparation, and to become a teacher and earn.”

“Teaching lessons?” The woman cries from insult. “My son is not from such a family that he could consent to engage in teaching on hourly pay.” She wants him to reach for more.

The Rabbi of the town came to greet me. He entered the room with a fervent smile of piety. He opened his remarks with praise and commendation for my good heart. He says he has brought a statement from the Sages of the town. He explains to me, kabbalistically, that the thirty–two rubles, which the Committee pays him monthly, are not enough for him and the six members of his household, so he requests an addition.

Then a short Jew with small, piercing eyes full of anger enters cautiously, closes the door, looks sideways and begins talking with a low emotional voice. He does not request anything from me. He has come to me to open my eyes and let me know that all the aid, which we give the inhabitants, has not helped. Not only that, but it brings harm. The only ones who need aid are widows and orphans. For their needs, a sum of one thousand rubles per month is sufficient, and the remaining fifteen thousand rubles per month, they leave on the deer's horn, meaning, they waste the money away.

“I am not saying, God forbid, that the Committee is misappropriating the money,” he said mildly, “but don't you understand that around a fat pot the hands become fat and everyone's hand is in it?”

“And what is there to do?” I asked him. “What?” he cried heatedly, “No money! You have made all of us beggars, especially those with extended hands! It would be better if you would lobby that they should allow us to return to our homes in Podvolochisk. And we would stand there on our own feet, and again be human beings.”

After him came a few members of the Local Relief Committee, for the representation of local householders and local exiles. Those who came were only representatives of the exiles. Homalski had already told me that the relations between the two parts of the Committee are not peaceful. According to the first few words, I recognized that the members of the Committee of the exiles were completely contemptuous of the local members. Podvolochisk, whose exiles to Skalat are in the great majority, was always a city of ‘Important People’ while Skalat was always considered a ‘City of Beggars.’ Now the wheel was reversed, and the people of Podvolochisk were forced to be at the mercy of the people of Skalat. The people of Skalat are not able to understand why the Committee donates to the exiles, and it allots only a few hundred rubles to the local inhabitants. At the same time, they try with all their might to prevent the exiles from returning to their homes in Podvolochisk, and the matter is not surprising. Every month, they receive more than two thousand rubles in rent from the exiles, aside from other income that they bring in.

The number of Jewish inhabitants of the place amounts, all told, to three thousand souls. Of those, 1,057 are considered poor. Part of them, 534 souls, are war–injured. And they have the right to receive support. They receive aid from the Zemstavot Organization. The exiles, most of them from Podvolochisk, found here, number 1,897 souls. Of those, 1,781 receive aid. The allocation for the month of January amounts to 16,209 rubles – 14,400 for the benefit of the exiles, 900 for the benefit of the needy of Skalat, and 900 rubles for the Jewish residents of the surrounding villages.

I use my free time to visit the residences of the exiles and to consider the city. The single largest building by which the city is distinguished is the synagogue. It is built of bricks. They say that the first stone in the foundation of the synagogue was laid by Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev. So too that the “Righteous Convert” visited the synagogue.

When he approached the synagogue, he bent to his knees and entered by crawling into the synagogue. And he approached the Holy Ark upon the benches. When they asked him the reason he walked that way, he answered, “Upon this floor stood people so great and holy, and I am not worthy to stand on the place which their feet trod upon.”

Now, the floor of the synagogue has been trampled by the feet of the exiles. They sit crowded and pressed together in the synagogue in every corner. They add their baggage, their bundles and their beds as if they are in a way station at the time of a panicked retreat.

I visited many camps of exiles. One dwelling particularly made an impression on me. It had a large room, one of its walls half inclining, and there were inside it large spaces covered with torn garments. The walls were draped with frost. In this room dwelled a woman in childbirth and several sick people. Afterwards, the husband of the pre–partum woman came to me at my dwelling place. He requested that they should give him double bread, and that they should add to the measure of wood and milk that come with his portion. I fulfilled his request and gave him three rubles cash.

In the evening, Mr. Homalski came to the Committee session. Homalski read the budget listing, according to which the local needy were allotted only nine hundred rubles. The local members of the Committee rose up and announced that they did not find that sufficient.

According to our records, 534 poor who suffered from the war were listed. A third came to us and at least one fourth of the sum of money was allocated, amounting to four thousand rubles.

Concerning this, Homalski said, “The Kiev Committee appropriated aid to the exiles, simple and poor, and even war injured, like those who remain living in their place. We have in Russia numbers in the millions, and the Committee cannot afford to come to their aid. The Local Committee needs to be concerned about their benefits.”

“How can you compare the communities in Russia to those of ours?”

Hearing these words, Homalski became angry and cried out:

“To whom do you tell your stories? Don't I know the situation in Skalat? I know that with you there are people who, in the days of war, acquired wealth. The city profited a great deal and there is in its ability, the means to support the local poor. It is possible that even the nine hundred rubles which I allotted were superfluous.”

“Who told you that the city became rich? That is only a fake report, which the Podvolochiskers circulated. They are envious of everyone”, cried one of the locals heartily! “I decided to add another two thousand rubles for the benefit of the local poor.”

By Hadassah Katz

My desire is to commemorate my childhood home, my father's house, where I drew the strength to live my life. I carry the memory of that home in my heart. Time has the power to heal wounds, but not those that are in my soul. The horrors of that time only deepen the wounds, which I will take with me to my eternal rest.

I want to set down in these few words some of the things that characterized our town. Skalat was not only a city of Jews. It also had a large Christian population that harassed us every day, and made our lives difficult. Both Jewish children and young adults grew up in the midst of a population that was hostile to Jews.

A profound memory that I can see through the distance of time, a great occurrence for all the Jews of Skalat, was the annual visit of the Rebbe to our shtetl. On the eve of the Shavuot Festival, every year, the Rebbe of Husiatyn would visit our town. The Jews rejoiced at his arrival. He was a ray of light in the life of the Jews of Skalat. He brought profound joy mixed with the grayness of our fight for existence. Our hearts yearned for the merit of his blessing, his encouragement and his advice. Hassidic fervor filled our hearts.

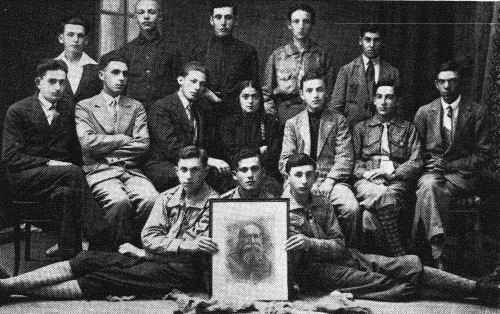

The beginning of our young adult lives was spent in the embrace of the activity of Zionist youth groups. We rebelled against the certainties, the routine, and the parents who did not encourage our participation in our Zionist dream. Our ally was the Hebrew Day School, which taught us about youngsters striving to settle in the Land of Israel. We studied Hebrew and Hebrew literature. In the halls of Zionist youth clubs, forbidden by some of our parents, we secretly worked to achieve our Zionist dream. At our gatherings, we expressed our distaste for our secular Polish education, where the Christian students expressed their hatred towards us. That was the beginning of the great human tragedy, which we did not entirely understand. Among the millions who perished, were the Jews of Skalat.

We incorporated these feelings in our daily lives along with the new ideals filling our souls, the dream of Aliyah. The charitable giving of Zionist youth in our city constituted an expression of our Zionist fervor – the Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael, the Permanent Fund of Israel, and the Keren HaYesod, the Foundation Fund, and all the Zionist parties – Beitar, the General Zionists, the Mizrachi – these were our contributions to the realization of Aliyah in the Land of Israel. The “Unification” gave its portion for this purpose, each one in its own way, for the common goal of building the Land of Israel.

I operated within and devoted most of my energy to Gordonia, the Pioneering Socialist Youth Movement, established in Poland in 1925, and named after A.D. Gordon, whose writing and teaching on Labor Zionist settlement in Palestine formed the ideological foundation of the movement. Many of the children of Skalat were educated within the movement, and there they found a home for their love of Zion. Many who had a difficult childhood found that Gordonia offered them a source of creative joy.

It was clear to us that without the consciousness created by the movement, we would not realize our ideals. We organized summer settlements. We arranged conferences, to which we would flee at any opportunity. We were in need of much strength for the realization of our dream. The environment in Skalat did not always nurture our spirit or our aspirations. Jewish youths from petit–bourgeois homes went to agricultural Hachsharah, preparatory experiences needed to become tillers of the soil in the Land of Israel.

|

|

In the area surrounding Skalat, we organized a Hachsharah farm. For the enhancement of our preparation, we reached out to more distant places. We struggled and we prevailed. We bequeathed this heritage to our children, who stand guard over our freedom in the Motherland, Eretz Yisrael, to this very day.

May my words be a memorial candle for my parents, my brothers and sisters, and all the Jews of Skalat who marched in the paths of affliction and grief, both low and oppressed. I remember with heavy heart and revulsion those who, in order to save their own lives, led our loved ones to death and aided the Nazi murderers in their detestable work.

I will never forget my father's house, or my mother's Shabbat candles, her eyes filled with tears when she poured out her soul in prayer and supplication.

|

|

|

|

fulfilling our mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied, sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Skalat, Ukraine

Skalat, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Lance Ackerfeld

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Dec 2020 by LA