|

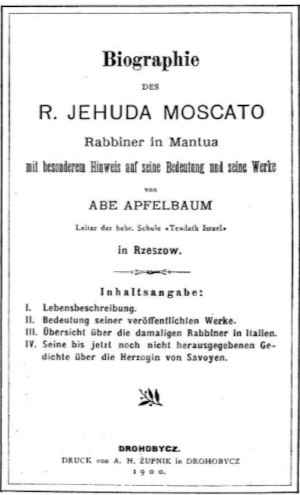

by R. JEHUDA MOSCATO Rabbi in Mantua With special reference to the significance and the works of Abe Apfelbaum Director of the Hebrew School “Teudat Israel” In Rzeszow. Table of contents:

Printed by A.H. Zupnik in Drohobycz 1900. |

|

|

[Page 488]

by Tzvi Simchah Leder

Translated Libby Raichman

Abba Appelbaum

Abba Appelbaum, an educated man, and a Hebraist, was one of the four founders of the Chovevei Tzion[1] organization in Rzeszow. He also founded the first modern Hebrew school in the town and Jews from the educated circles in the community, gathered around him.

|

|

Already in his youth, he was a contributor to various Hebrew newspapers of that time. He was associated with famous Yiddish and Hebrew historians, with whom he conducted a regular correspondence. One of those was the renowned professor, Abraham Berliner.

Abba Appelbaum devoted himself to researching the lives of Jewish scholars in ancient times. He took a particular interest in Jewish scholarship in Italy. He wrote a biographical book about Reb Yehuda Moscato who was the Rabbi in Mantua, three hundred years ago. The biography was published in 1900. He also wrote the biography of Reb Azariah Figo, the author of the book “Binah L'itim”, that was published in 1904. The third biography that he wrote, concerned Moshe Zachuta, published in Lemberg in 1926. Aside from these dissertations, he also wrote many articles in Hebrew about Chibat Tzion[2] and other Jewish issues. He was a great master of the Tanach and a Talmudist. From his youth, until he was advanced in life, he was an assiduous student of Talmud. Day and night, he sat and studied Sh”s[3] and commentaries on Jewish law, legislature in Talmud, Rabbinic literature, and legend. He also wrote in Yiddish and he and Naftali Gliksman, were co-founders of the Rzeszow “Folks Tzaitung”[4]. He died in Rzeszow on the eve of the first night of the festival of Shavuot 5693, corresponding to 1933. His funeral took place on the first day of Shavuot.

Naftali Gliksman

At the beginning of the 20th century, if one spoke about Hebrew in Rzeszow, Naftali Gliksman immediately came to mind. Hebrew and Naftali Gliksman were one.

He was the leader of the educated residents in Rzeszow, and the only Hebraist, who valued Yiddish language and literature highly. Such was his character, that his editing of the “Naiye Folkstzaiting”[5], was not done with the intention of receiving an award. With his journalistic talent, he helped to spread Zionist ideals, not only in Rzeszow circles but also in the entire province. Through his articles he assisted greatly in combatting the local assimilating

[Page 489]

cliques and aided in the selection of Zionist candidates in the community elections.

Naftali Gliksman was born in Kriftsh in Galicia. (He was in fact called by the nickname “Kriftsh”). He was the great-grandson of the Chassidic Rabbi, Reb Dovid Kriftsher (the holy man).

Naftali was small in stature but of high intellect. His face was adorned with a beautiful red-haired moustache, and a head of red hair. He was a man burdened with a large family. If he had devoted all his time to the teaching profession, he would have had a respectable income, but he set greater store on his Zionist ideals than on earning a living, and for this noble goal, he gave up the best years of his life in Rzeszow.

He was a Chassidic young man and studied in the small synagogues and yeshivot[6]. When he was 17, he also began to read books about Jewish Enlightenment, and in this way, he gradually turned towards it.

Shortly after he married a girl from Rzeszow, he was drafted into the army. Later he became a Hebrew teacher. He also devoted time to Yiddish and Hebrew journalism. His journalistic activity began when he became a correspondent for the newspapers “Carmel”, and “Der Vekker” [The Awakener]. His articles were also published in the Viennese newspaper “Yiddishe Velt” [The Jewish World], and also in the weekly “Drohobitsher Tzaitung”[The Drohobitsh Newspaper]. In Rzeszow in1908, he founded the “ Naiye Folks Tzaitung” [The New Folk Newspaper], a Yiddish weekly. Under his editorship, the newspaper had a large following. Other weekly newspapers were published in Rzeszow, but not one of them survived. His editorials were treasures of Yiddish journalism.

Later he became a contributor to the “Lemberger Tognblat” [The Lemberg Daily] and also to “HaMitzpeh” [The Watch-Tower]. He also wrote a book “Darchei Chaim”[7]. He immigrated to the Land of Israel where he Hebraized his surname to “Ashriel”. Naftali Ashriel died in Petach-Tikvah where he was a principal of a religious school.

Moshe Dovid Geshvind

Moshe Dovid Geshvind belonged to the older generation of educated Rzeszow residents. He dressed in modern attire, something that was an extraordinary phenomenon in Rzeszow at that time, in the years 1860-1870, when the Chassidim thrived. Herzl's Zionism had not yet existed. In his youth, he devoted himself to spreading the idea of enlightenment among the Rzeszow youth, which at that time was not an easy task. When I came to know him, he was already an old man suffering with hearing loss. He was even highly regarded among the religious Jews and was also an eminent figure in community circles.

|

|

Moshe Dovid Geshvind was born in Rzeszow in 1846. He was raised in a religious Jewish atmosphere where he was taught about Judaism and also studied Hebrew. When he was a young man, he was already a writer for the most important Hebrew newspapers. In the 70's of the last century, he was secretary of the Rzeszow cultural organization, a position that he maintained for over 30 years. He was also an official translator in the Rzeszow courts where he translated Hebrew and Yiddish documents into Polish.

Geshvind was an accomplished Hebraist. In his youth, he wrote Hebrew poetry that was often published in the Hebrew journals of that time. In 1883, he released a collection of poems by the Polish poet Slovatzky, in Hebrew. He also left behind a book in his own handwriting “Divrei Chachamim”– a lexicon to the legends of the Talmud. He died in 1905.

[Page 490]

Chaim Vald

The “Chovevei Tzion” organization, the first Zionist organization in Rzeszow, was founded by four intellectuals. One of them was Chaim Vald, also one of the pioneers of the local Zionist movement. He was very popular, not only in Rzeszow, but also in the Rzeszow vicinity. He was the only Jew in Rzeszow who had a good sense of political wisdom. He was a political psychologist – who assessed the qualifications of the candidates and never erred. The Jews in the town, often demanded an explanation from him regarding his political opinions. Chaim Vald was a politician in the true sense of the word. When I say “politician”, I do not mean God forbid, in the sense of the current politicians who use their political careers for personal goals; Chaim Vald's political purpose, was only for the good of all. He was only interested in ensuring that the candidate for the community position, or for the council, should be deserving of it, and provide for the needs of the local population.

At the beginning of the 20th century, I met Chaim Vald and remember him well. He was a well-built but a slim young man, with a small beard and two short sideburns that hung straight, not curled. He had a store in the street, not far from Rabbi Reb Lozerl's house. Part of the day, he was busy in his small store, but no sooner he appeared suddenly, in the market-place, he was encircled on all sides by those who wanted to speak to him and hear his political opinions.

Here stands Chaim Vald with his little stick in his hand, in the market-place, close to Koshtshushkos monument. Standing around him, is a group of Jewish people, bombarding him with questions. A discussion about important matters and events develops. Chaim Vald speaks, his audience hanging on his every word, because he simply does not talk about inane issues; in fact, he speaks only a little, but what he does say, is well-considered. He was the “Rabbi” of local Jewish politics, and the Rzeszow Jews were his political Chassidim.

When the time came for the community elections, he was one of the most important figures in the political turmoil, not because he was standing as a candidate for a position. No, Chaim Vald was never a community candidate – he stood guard to ensure that the community candidate was qualified for the position. The result was that the candidates that he supported were always elected.

Chaim Vald was the main figure at the political gatherings. He was an outstanding speaker. He was very serious when analyzing the good qualities or the shortcomings of the candidate. As a young Chassidic student, I was an opponent of Zionism, but I was a political admirer of Vald. At the time of the elections, I often came to the gatherings where he spoke. He was the best political speaker in Rzeszow. The old doctor Smuel Raich, an eminent Rzeszow advocate and head of the community, thought very highly of Chaim Vald and his political opinions. No matter where Chaim Vald spoke at a gathering, Dr. Raich appeared. The year I left Rzeszow, in 1913, was Chaim Vald's most brilliant year in his political career.

Moshe Vizenfeld

When I was a young cheder-boy of about 10, Moshe Vizenfeld was already an adult religious student of about 17. In the town, he was known as a young genius. He was truly a great student. He was the only one of the young Rzeszow religious students, to whom the town's Rabbi, Rabbi Heshil Valershtein devoted himself, and even studied with him. Vizenfeld had a strong will to learn. In his youth, he was already a learned scholar. He grew up in a religious environment and devoted himself extensively to Chassidut[8]. Due to his great desire to study, he was not satisfied with learning only Talmud and its commentaries, and he began to study Kabbalah[9], but later, he turned to Jewish Enlightenment and also adopted Zionist ideals.

I remember him well from the years when I was a young student in the small synagogues. The young students had already distanced themselves from him because he was a Zionist and a non-believer. Yet, he would often come to the synagogue where there were a few boys with whom he was in contact, and whom he brought closer to Zionism. One of them was Sholem Azshe, the son of a ritual slaughterer. Vizenfeld was a handsome, well-built young man and when he spoke, he spoke politely and easily and influenced his audience.

As I mentioned earlier, the Chassidic youth of the small synagogues regarded him as one who acts without constraint, and they distanced themselves from him. Meir Ellenbogen was one of Vizenfeld's friends, and a grandson of the Satanover Rabbi. They studied together and worked to spread Zionist ideals. They established the first Zionist youth organization Ha'Shachar” [The Dawn], whose premises served as a meeting place for the Zionist youth and existed until the day that the Jewish community of Rzeszow was obliterated by the Nazi murderers.

[Page 491]

Moshe Vizenfeld was a contributor to “Ha'Mitzpeh” and other journals. He was also one of those who published the new “Folks-Tzaitung” in Rzeszow. He also wrote articles for the “Lemberger Togblat”, whose editor at that time, was Moshe Kleinman. Later, he also became the Galician correspondent for the “Yiddishn Morgn Zshurnal” [The Yiddish Morning Journal] in New York. He perished as a martyr, together with the Rzeszow Jews, in the last world war.

Leon (Levi) Chaim

At the beginning of the 20th century, Leon Chaim was one of the most educated people in Rzeszow. He was also one of the first Zionists in the town who helped significantly to spread the Zionist ideals among the Rzeszow youth. He also took an active part in all the cultural activities, and for this reason, he became very popular among the modern Jewish intellectuals. He was highly educated in the classics and mastered a few languages.

When I met him in 1907, he had already acquired significant status in cultural circles. At that time, he was the business manager of Eloise Frelich's office and money exchange that was situated at the front of the magistrate's building in the market-place. This was a private bank that engaged in the exchange of foreign currency. The owner was the son of Wolf Frelich, an eminent Rzeszow proprietor. He left the entire management of his business in the hands of Leon Chaim, whose competence ensured that the business functioned at a high level.

Leon Chaim's father had a tavern on the outskirts of the town at the Boshnia. The tavern was encircled by a large garden with beautiful trees and plants, where many benches and tables were arranged. In the summer, many people would come there, to sit in the garden with a glass of mashke[10]. The venue was well-known in the town because of the good quality sour milk with sour cream, tasty triangular pieces of fresh or dried white cheese, and other delicious treats that were served there. The Boshnia was quite a distance from the town, yet people from the vicinity took the long walk there. In the years when I was a Chassidic student in the small synagogue, I recall how the Chassidic Jews and young boys would go to the Boshnia tavern on Lag Ba'Omer to observe the anniversary of the Cabbalist, Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai.

Kalman Kurtzman

Kalman Kurtzman was also one of the four founders of the “Chovevei Tzion” organization. He was also an educated person with a general education. In my time, he was the secretary of the Rzeszow cultural community, a position that he assumed after Moshe Dovid Geshvind resigned due to his age.

Kurtzman was the opposite of Chaim Vald and Abba Appelbaum. He did not have a beard or sideburns, and his attire was “Germanic”. As secretary of the community, he was an influential person, and the members of the community – from the president to the community council – held him in high regard.

He had a difficult and responsible role. In recent years, before the war, Rzeszow had a large Jewish population. Members of the community attended the meetings, only to take decisions, but the actual daily functions of the cultural organization were performed by Kalman Kurtzman. The community's administration office was a place where people came and went, the whole day. Kalman Kutzman gave each one the information and help that they needed, and treated everyone in a friendly manner, and with respect. He not only controlled the administration offices, but also everything that was connected to the community, or was under the community administration. He was therefore loved by everyone. He was also one of the pioneering Zionists in Rzeszow.

Naftali Tuchfeld

Among the Rzeszow inn-keepers, Reb Dovid Tuchfeld, held a most honorable position. This was not due to the fact that his tavern was more beautiful or better, but rather because of his three sons, of whom Naftali the youngest, was the most loved and popular among the young men and among the important leaders in the community.

Naftali's father was a respected religious Jew who prayed in the large synagogue with his three sons who were religious young men. Here, they were dressed in beautiful velvet Fedora hats, and long fur-lined coats. The oldest son was extremely observant, and prayed with Chassidic fervor, in the manner of the Belz Chassidim.

The Tuchfeld's tavern was the gathering place of the prominent dry-goods merchants, such as Yosef Faivel, Zecharia Yezshaver, Herman Lubash, and others. Every evening, one would see them sitting there with a half pint of wine, enjoying themselves socially. The tavern also served as a place for important people, as, for example, Reb Avremele Babad, of the orthodox group.

[Page 492]

I remember Tulek Tuchfeld as a young boy of Barmitzvah age. Already then, he was involved in politics, and also in general world issues. I often saw him sitting in the synagogue, participating in discussions with Avremele Babad and other prominent people, all of whom, already thought highly of him. His conversations were often mixed with humor, and what he said, was intelligent and logical.

In his father's tavern, where he assisted with duties, the successful merchants enjoyed the company of the young Tulek, more than that of their older friends. After the war, he went from Russia to Tel-Aviv, where he became very active in the Organization of former Rzeszow residents, and in the Mizrachi[11] organization. In recognition of his services, the Minister of Religious Affairs transferred a division in his ministerial office to him. He died in Tel-Aviv.

Translator's Footnotes

by Dovid Tuchfeld, Ramat Gan

Translated by Libby Raichman

Like all other larger and smaller towns in Poland, Rzeszow also had its Rabbis and Chassidic Rabbis, its honorable people, its leaders, and its community workers – but the persona of Naftali Tuchman was one of a kind.

Naftali Tuchman had a flair for politics from his earliest years. In this regard he was influenced by his home environment that promoted political interest. For many years, consultations and gatherings regarding community and council elections, as well as elections for the Zionist congresses, took place in the premises of his father's wine-store.

After the First World War, the Balfour Declaration of 1917, brought the revival of various Zionist movements. Naftali Tuchman became known as one of the most active members of the “Mizrachi” movement. His influence spread not only in Rzeszow - but he also became known in all of western Galicia. He took an active part in national and world conferences of “Mizrachi”, and on a few occasions, he was a delegate to the Zionist congresses. After the death of the Rzeszow Rabbi, Rabbi Natan Levin, Reb Naftali was part of a delegation to Sombor[1], to propose that the Rabbi's son, Rabbi Aharon Levin, assume the chair of the Rabbinate, as the Rzeszow Rabbi, a position he would fill after a few months. At the same time, Rabbi Aharon Levin was the representative of the Religious Party to the Polish parliament. In the beginning, the relationship between Naftali and the Rzeszow Rabbi was entirely appropriate. However, the situation between the two changed because the Rzeszow Rabbi, Aharon Levin would not agree to the Dayan[2], Rabbi Yosef Raich becoming an official dayan, because he suspected that Rabbi Yosef Raich, was a sympathizer with the Mizrachi movement. (Naftali was a prominent member of the Mizrachi movement). The relationship became more aggravated when,

|

|

[Page 493]

at the last community elections, the organization released its list of candidates and nominated the Jewish assimilated candidate Dr. Maximillian Vizner. This resulted in a great outcry in national circles. Naftali brought about the creation of a partnership bloc between the Chassidic list of candidates of Reb Asher Zilber, and the Zionist parties, that was very successful. Reb Asher Zilber was again elected as head of the community, and the Zionist parties had considerable influence in all matters in the town. Naftali Tuchfeld was elected as deputy to the head of the community, and as a member of the town council.

In 1937, when Naftali's father-in-law, Leizer Salpater, died in the town of Myeletz[3], Naftali was forced to leave all his activities in Rzeszow, and travel with his family to Myeletz. However, after a long time, Reb Asher Zilber, the head of the community, missed Tulek's presence and often called him to Rzeszow to consult with him on various issues.

The tragic day for Polish Jewry came on the 1 September 1939, with the outbreak of the Second World war. Together with thousands of other Jewish families, Naftali and his family left the town of Myeletz, wandered eastwards, and arrived in Sombor.

In September 1939, the Russians seized East-Galicia, and in June 1940, together with tens of thousands of other refugees, Naftali was sent to Siberia. Without considering the difficult situation and great danger, Naftali entered into correspondence with Mizrachi leaders in Israel, not suspecting that the Soviet regime was censoring his correspondence. As a result of this, Naftali was arrested, apparently for espionage.

The war was coming to an end, and with the general liberation of the refugees in Russia, Naftali was also liberated. He returned to Poland in July 1946 and settled in Krakow with his family. Here again, with renewed energy, and without consideration for his physical suffering and his harsh experiences in Russia, he again devoted himself to the Mizrachi movement and the Jewish community in Krakow.

Naftali was invited to Warsaw by the Central Board of Communities, and was nominated by its chairman, Rabbi Dovid Kahana, as his deputy. However, his thoughts of realizing his old dream of immigrating to the land of Israel, did not leave him. In May 1948, he farewelled his friends in Warsaw and Krakow and travelled to the Land of Israel.

En route to Israel, Naftali spent some time in Paris. In July 1949, he immigrated with his wife, children and grandchildren.

In Israel, he was employed as an official in the Ministry of Religious Affairs. At the same time, he did not neglect his activity in “Mizrachi”. Thanks to his efforts, he received a Torah scroll from the Ministry of Religious Affairs to perpetuate the memory of the Jewish community of Rzeszow. The Torah scroll was donated to “Bil'u”[4] synagogue in Tel-Aviv.

At a banquet arranged by the “Organization of former residents of Rzeszow” to mark Naftali's great merit, he suddenly felt unwell, and fell unconscious. His heart stopped beating.

In this way, one of the devoted and loyal sons of the town of Rzeszow, left us. At his funeral on 27 Tishrei 5604 (1953), eulogies were delivered by Z. Varhatig, the Minister for Religious Affairs, Rabbi Tchurzsh, Rabbi Bialer from Jerusalem, and Pinchas Shenman, the chairman of the Religious Council in Tel-Aviv.

Translator's Footnotes

by Simchah Zaiden

Translated by Libby Raichman

(The Tognblat, 19 June 1931)

The wider public knows – that possibly does not know Abba Appelbaum of Rzeszow as an old, enlightened writer and scholar who played a significant role in the Period of Enlightenment in Hebrew journalism. He wrote articles in “Ha'Tzfirah”[1], “Ha'Melitz”[2], “Ha'Magid” [The Herald], “Ha'Mitzpeh”, “Ha'Shaluach”[The Emissary], and “Ha'Olam”. He also wrote a few articles that he published. He was always in correspondence with great Jewish scholars, prominent people, genii, writers and historians. His name can be found everywhere in the Jewish encyclopedias, also in the Hebrew encyclopedia “Otzar Yisrael”, where he was a regular contributor. Now he is celebrating his 70th anniversary.

Abba Appelbaum was born in Rzeszow on the 23 June 1861, corresponding to 15 Tammuz 5621, to a family that was not well-off. He studied in a cheder until he was 12 years old, and then in the small orthodox synagogue. After he married, he entered into written correspondence with great Jewish personalities where he negotiated on matters of Halachah[3] and Responsa[4] with many Rabbis, like the Rabbi, the Gaon[5], the mystic, the of blessed memory, author of “Harei BaShamayim” [Behold in the Heavens] In the Responsa he is mentioned with the sign, n', Reb Abba Appelbaum.

[Page 494]

Abba Appelbaum wrote his first articles in the assimilated periodical “Ha'Mazkir”[The recorder], in Lemberg in 1882. Then came the Period of Enlightenment, and he became a contributor to the Hebrew press. In the past year, in the publication “Ha'Olam”, he wrote many scholarly historical articles, about great Jewish personalities. Appelbaum is highly regarded in Jewish historical literature for his articles about the Gaonim, and the Italian scholars. His first book “The History of the Jews of Moscow”, was published in 1900, and his second work, “The History of Reb Azariah Figo”, was published in 1907. Recently, he published a new treatise “Reb Moshe Zachuta”.

Abba Appelbaum was one of the first founders of the “Chovevei Tzion” movement in Rzeszow, the founder and head of the first “Ahavat Tzion” [Love of Zion] Association, and the founder and head of the Hebrew school. Today, his students are scattered throughout the world, like the Rabbi Dr. Yechezkiel Levin, in Lemberg, Professor Dr. Moshe Alter in the “Tchachmonei” High school in Warsaw, Dr. Tzvi Koretz, a Rabbi in Berlin, Professor Dr. Shlomo Horovitz in Vienna, Dr. Moshe Y'ari cultural secretary in Tel-Aviv, Dr. Ovadiah Aizenberg, secretary of the League of nations in Geneva etc.

In “Otzar Yisrael”[The Treasures of Israel], one finds many articles by Abba Appelbaum, like for example, about the history of “Venedik”, and about “Moshe Zachuta”. Nochum Sokolov cites Appelbaum's composition “Moshe Zachuta”.

It is particularly interesting to sit with Abba Appelbaum when he shows you a large number of letters from the greatest Jewish scholars with whom he was in correspondence: Dr. Shlomo Rubin, Professor A. Berliner, Professor Bichner, Professor Rabbi Poznansky. In writing about Abba Appelbaum, Reuven Brainin writes that he said a “Benediction of Enjoyment” over his work; also Dr. Kaminka, Shlomo Horovitz, Rabbi Castilliani of Rome, the Chief Rabbi Dr. Gudeman, Dr. Shlomo Buber, The Rabbi, the Kohen Shlomo Kook. This is what Dr. Max Nordau writes about Appelbaum's work “Yehuda Moscato” : “With particular interest, I read your book and found it to be a praiseworthy contribution to the history of our brothers in Italy.

Dr. Binyomin Schlager, an Advocate by profession, was a philosopher and a writer who published a few books in Polish. He took part in the Zionist life of Rzeszow, and for a short time, was also the president of its community. He always had a friendly smile, had a large “philosophical forehead, and enchanting intelligent eyes, a kind of modern “Spinoza”.

In his work as an advocate, he was also a creative thinker. I want to relate here, an occasion when he defended a ritual slaughterer from Lantzut[6] who had been accused by the police of breaking the law preventing cruelty to animals. In this case the calf lay bound for one minute longer than was legal, before being slaughtered. According to the law, this was a serious crime and Dr. Schrager realized that the slaughterer could expect severe punishment, so he led the defence ostensibly in the name of the slaughtered animal … Due to Dr. Schrager's imaginative defence, the ritual slaughterer was freed.

I often had the opportunity of speaking to him about his dissertation ”Spinoza”, that impressed the philosophers, and he was invited to the Spinoza ceremonials at Hag in 1927. In his dissertation, Schlager asserts that the “substance” of Spinoza's work, is a kind of mystic-gate, “infinite” … Spinoza would have cast fire on those who would dare to say that Jewishness ends in the synagogue, those who excommunicated Spinoza, in his time … . A synagogue is not merely a Western Wall where Jews have a good cry, only with prayer – a synagogue is our home, a fatherland that wanders with us, throughout the diaspora.

His second book, “S'demert Dos Hartz” [The Dawning of Passion], is based on the legendary theme of King David, Batsheva, and her close friends. It is a small book, with not even a hundred pages, divided into chapters, each of which stands alone in a heart-stirring tale, of a holy fire that is ignited, and it is not known from whence it comes – from the heart, or from the mind … . Each chapter is independent, in an instant burst of splendor and beauty, profound thought and sincere love.

The Polish literary critics labelled this book, a literary sensation. The writer showed me a letter from Stanislav Pshibishevsky, where he writes about his book. Pshibishevsky wrote the letter three months before his death.

Dr. Binyomin Schlager published a few more books such as “Der Her in Hentshkes” [The Gentleman in Gloves], and “Der Talyan” [The Executioner]. The latter was confiscated by the censors. The book deals with a theme, where a poor, unemployed man, sells his body while still alive. The prose in all his work, is in the Polish language, original and brilliant.

(Togenblat 28 January 1931)

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 506]

by A. Tabatshnik, New York

Translated by Libby Raichman

I became closely acquainted with Berish Vineshtein 21 years ago; we are now celebrating his 50th jubilee year. Although I am missing six years to align with the 27 years of the official chronology of Vineshtein's creativity, I can however say with pride that I was one of the very first that recognized and acknowledged his artistic strength and the poetic merit of his work. The poems that he showed me in the first days of our acquaintance and friendship, made a strong impression on me. I would take copies of his poems from him, and run with them to show friends, as if I had won a jackpot. Those who had a genuine feel for poetry, admitted immediately that Vineshtein's work was something new in Jewish literature.

When Vineshtein's first book “Bruchvarg” was published 19 years ago, it was truly a literary sensation. Important writers then came to the evening in honor of its publication and had great praise for the original nature of Vineshtein's poetic talent.

As happens in such cases, Vineshtein's success aroused a little, and perhaps more than a little jealousy, and an attempt in certain literary circles to diminish his worth. This, however, did not harm him and he continued on his path. It was not a smooth path. He was aware of pitfalls and even of failures, just as he was aware of success; but this is the path of every artist. There is no smooth path in the arts. Those who convince themselves that the path of creating is a smooth one, slide on the smoothness for so long, or for so short a time, until they slide out of the art of words.

What I, and I believe others too, were so fascinated by their first acquaintance with Berish Vineshtein's poems, was really his lack of fluidity. He was not a poet who came to poetry to live off his reserves, or that of strangers. He brought his own content, and his own way of shaping the content. Of course, the accomplishments of his predecessors in Yiddish poetry were not lost to him; he recognized the accomplishments of the older Moshe Leib Halperin, and the young man of that time, already an extraordinary poet, Abba Shtoltzenberg. The principle, however, for Vineshtein, was not how much he had learnt from literature, but how deep and how painful it was for him

[Page 507]

as one who learnt from life experiences. And a poet who approaches his work from life to literature, and not from literature to the desk, no matter how influenced he is by one or another poet, must have something new to contribute.

At a time when others were emulating, and following literary trends, Berish Vineshtein had his own style. He allows his own style to be coarse, unrefined, not cultivated; it does, however, breathe with life, with authenticity, with first-hand observations, and with painful experiences.

In poetry, progress often means going back precisely to the beginning, to the primitive. In Vineshtein's work, we, his friends, saw a disconnection from predominant literary stereotypes, and a turn to the source of each authentic creation – to life, to the primitive. However, for Vineshtein, the disconnection from literary stereotypes did not mean disconnecting from established traditions of Yiddish literature, but actually a continuation of those traditions.

I will not be able to dwell upon the more personal, I would say, spiritual Jewish traditional qualities of the person whose anniversary is being celebrated. Not here, where space is confined. I will, therefore, be satisfied with only a few observations in this regard.

Today, every reader of Berish Vineshtein's poems, is aware of his strength to observe, to describe, and to portray images directly from life. The question of poetic review, however, is not so simple. After all, every person has their own view. One should never make the mistake and think that observing poetry is simply a physiological or physical matter. When the poet writes, the object is not in sight, like the model who poses for the painter.

In reality it means that the poet has the imagination, that he is able with his personal, spiritual eye, to see, truly and precisely, as if the images were in fact, in front of him.

Vineshtein's images do not provide us with photographs, rather artistic truths. His images portray the character in a mysterious light.

These are not only individual images but also descriptions of entire situations, of lonely people in the big town, the youth of the Volye[1]. These are not imitations, rather poetic forms of reality. To see figures and objects the way Vineshtein saw them, one needs not only eyes, not only healthy senses – but a heart, poetic feeling for the loneliness that people feel, an artistic flexible sense of courage, and an understanding of the physical beauty that reveals itself in the primitively-healthy person.

Vineshtein's poetic imagination, even though it is flexible in its expression, is not determined by its external image, but by its innermost world, that he carries within him. As a child of the First World War, as an eye-witness, not only to one destruction, Vineshtein bears within himself, deep sorrow and compassion for everything that lives and suffers.

One of the most pronounced signs of a poet is his language. However, the language of a poet is not necessarily flippant, or eloquent. Vineshtein's language is not a polished “literary” language. It is the language of our Jewish life, of our familiar way of life. It is, however, also the language of matters in the universal sense of the word, as well as the language of Vineshtein's particular lyrical mood. His language, that is so ethnic-idiomatic, is at the same time also very authentic and individual, and even refined.

Although Berish Vineshtein's language is more connected to the “eye”, given his strength to visualize, rather than to the ear, and his strength to hear the music of words, so that only the deaf would say, that he lacks rhythm, or even musicality. In essence, for a lyricist, his rhythm is an epic. Whoever is somewhat acquainted with prose, can easily see that Vineshtein's lines are drawn instinctively towards hexameter. The latter is particularly true regarding his poems in Bruchvarg; and the music is the music of sadness and longing.

And how much authentic traditional sounds, how much venerated rhythm – I mean the sounds and the rhythm in our bloody chronicles and Lamentations – these are elements that exist in Vineshtein's powerful poem called ‘After a Thousand Years‘.

As mentioned, I must be satisfied here, with pointing out in just a few lines Vineshtein's poetic features. I have, for example, not touched upon his development in the 19 years since he published his book Bruchvarg, and his becoming engrossed in our tragedy, in his desire to eternalize the beauty and the holiness of the Jewish person. One must not forget that Berish Vineshtein, who portrayed the “ Yungen Fun der Volye” with so much authenticity, portrayed the world of fine Jews with no less authenticity. The holy Sabbath of Rzeszow follows him, exactly like the weeks.

[Page 508]

In the years of the destruction, Vineshtein became engrossed in the Jewish past. He made attempts to demonstrate, that in every phase of Jewish life, God rested. In the simple, most ordinary, busy Jew, he wanted to catch sight of a reflection of our forefathers, of our Gaonim[2], and our righteous. In every corner of the world, where Jews lingered in their long and tragic exile, they wanted to see the Land of Israel, they wanted to see Jerusalem and Tzfat. In these attempts, Vineshtein set himself extensive goals, the same goals that the greatest of our poets attempted. His attempts were not always successful . Perhaps, in addition, it needed greater ideological preparation. But the attempt itself, like the attempt to have a hold upon a Titan of human spirit like Beethoven, is symptomatic of the earnestness with which Berish Vineshtein approached his profession as a poet.

He continued to pursue his work with this earnestness. From the beginning he considered his work, not as a personal matter, rather as part of folk-heritage that one cannot squander. He always felt that he had a mission to proclaim, that was related to the Jewish world, with its endurance and sadness, with its wandering and its dreams, with its Sabbath and festival ennoblement, its everyday activity, with its ancient lineage, scholarly politeness, and its common fraternity, crassness, and calm.

For Vineshtein, however, his feeling for family was strongest of all, and often the source of both his lyrics, and his epic poetry. Once, in conversation, he expressed that he has his grandmother Channale, the pious lady, to thank for his poetry, and that he honored her in more than one song. He carries her traditions as a holiness, a holiness that develops in his poetry with a special Jewish beauty… .

In his 50 years, Vineshtein can list many accomplishments. He already has his own three complete books of songs and poems. A fourth book “America”, that is a kind of sequel to his great poem “Rzeszow”, is to be published in the coming days. And if one can still await much more from him – then one would bear witness to the songs that he published recently – songs that excel in their fullness and maturity.

From “Di Goldene Kayt”, number 22, Tel-Aviv, Israel.

Translator's Footnotes

by Yanos Turkov

Translated by Libby Raichman

The poet Berish Vineshtein, who came from Rzeszow, celebrates his hometown in song, in his epic poem “Rzeszow”, a town with its Gaonim[1] and ordinary Jews: intellectuals, and shop-keepers; political parties, societies and libraries, together with all the institutions that it possessed.

Among the martyrs of Rzeszow was a simple folk-person, who held a distinct, authentic, and prestigious place in the town. His name was Nachum Shternheim and he was the troubadour of Rzeszow.

Shternheim came from a religious Rzeszow family. His father was an esteemed egg dealer who strove to make a Rabbi of his Nachum'l[2], or at least – a good student. He sent him to the yeshivah[3], but Nachum Shternheim became absorbed in Zionism and quietly became involved in the first Po'alei Tzion movement in Rzeszow. When his father came to know about it, he understood that his Nachum'l would no longer, be a Rabbi – may he at least be a mentsh [a decent and responsible person] – he asserted, when he sent Nachum to work as an attendant in a local fabric store; but Nachum's thoughts went in a completely different direction, and if that was not enough, at his work he

[Page 509]

sang strange songs under his breath the whole day and drove the rest of the attendants crazy with his rambling. The owner of the fabric store dismissed him with the following words: “you should become an actor in a Purim play, [a jester], not a human being …”

Nachum Shternheim felt like a free bird, that had been released from a cage. His father often took him along with him to the Chassidic Rabbi's courtyard[4], perhaps it would influence him – he thought. And Nachum willingly went to the Rabbi, and later to the “courtyards” of other Rabbis, where he picked up the tunes that they sang there.

Nachum Shternheim was good-natured, always smiling, and had a great sense of humor. He would grasp a joke quickly and repeat it well - and if his listeners reacted appropriately, he was overjoyed. He had a rich imagination and would tell a story beautifully. It is worthwhile relating one of the many stories that he used to tell.

|

|

1.

2.

3. |

|

When Sholem Aleichem came to Galicia for the first time, Nachum Shternheim decided to bring the great writer to Rzeszow as well. Nachum relates that the evening in the writer's honor was well organized and was to take place on a Sunday. Sholem Aleichem however, came to Rzeszow a day earlier, at dawn, that means, on the Sabbath. When Nachum caught sight of the distinguished guest, he was in shock ….

- What have you done, Sir Sholem Aleichem – Shternheim exclaimed, confused – you arrived on the Sabbath? ! They will stone the two of us together …

As Shternheim later told, he had to hide Sholem Aleichem for the entire Sabbath, so that his observant father would not notice him. That Nachum did not turn completely grey that day, was probably only, not to upset his father.

As soon as it became dark, Nachum Shternheim took Sholem Aleichem to the village of Strozshver where he spent the night. When Sholem Aleichem arrived by train in Rzeszow the next day, he received a royal welcome. Nachum Shternheim, as he himself described – set up an Arch of Triumph for Sholem Aleichem at the train station with an enormous banner inscribed with the name “Sholem Aleichem”. The whole town gathered there, and besides the Rzeszow youth, there were also religious Jews with long beards. When they saw the “German” Sholem Aleichem with a small beard and long hair, with a broad black hat on his head, and an even wider cape on his shoulders, the observant Jews stood there disappointed and shamed, that they allowed themselves to be deceived by the “clown”, Nachum Shternheim, and came to the train station….

The observant Jews did not attend the gathering, on the eve of Sholem Aleichem's departure. Only the youth were in the hall. Nachum Shternheim was the chairperson at the Sholem Aleichem evening, and he truly shone with happiness.

[Page 510]

Nachum Shternheim would wander through the streets of Rzeszow all day, always with a song on his lips. When one observed him and saw his contentment, and his good-natured smile, one would think how happy this person is …at the same time however, poverty reigned in his house.

When one came to buy a song from him, and asked the price, he would answer that the best price for the song would be when the purchaser would listen to another song of his …and indeed, immediately, on the spot, he sang his latest composition.

Nachum Shternheim would not only compose the songs , but - perform them himself. This gave him the greatest pleasure that one can imagine. He would travel to towns and villages to organize his song evenings. However, he had no understanding of finance. Whatever he was given, he took – if he was given anything at all.

Nachum Shternheim, as previously mentioned, was a frequent visitor to the Chassidic courtyard; his popular song “Sorrele”[5], was based on the life of the Rozvadov Rabbi's son Shlaymele. He composed his song “Malkalle”[6], at the time of the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in Russia, and masses of emigrants began to stream into Galicia. Among the immigrants arriving in Rzeszow, was a gorgeous girl named Malkalle, who, aside from her beauty, possessed enormous charm. This Malkalle made an extraordinary impression on him. He was carried away by her personality and composed the song that bears her name.

Nachum Shternheim wrote not only romantic and love songs. He also composed a sequence of war songs and time songs. When Boxing became a fashionable sport and all the youth were drawn to the sport, Shternheim created a scathing satire and ridiculed the youth who had exchanged a spiritual culture for a physical one – a culture of the fist. This theme served for his song “A Boks Metsh” [A Boxing Match], that was very popular in Galicia.

His songs, many of which entered deep into the soul, became folk-songs, and to this day are sung throughout the world. Aside from his magnificent song “Sorrele”, that was made popular worldwide by Diana Blumenfeld, another of his well-known songs “Shabbos Nochn Kugl”[7], was made popular by the deceased folk-singer Yossele Kalodne. To the list of Shternheim's popular songs “Hob Ich Mir a Nigndl”[8] that was adapted by Shlomo Prizament, should be added, as well as “Dos Boimelle”[9], for which the Cantor Bri, wrote the music. Another of Shternheim's songs that became popular, was the war song “Frytik Oif Der Nacht”[10] whose music was also written by Cantor Bri, who is from Rzeszow.

Before the war, a book of songs by Nachum Shternheim was published in the United States of America.

Shternheim was happy when his songs were sung, but – happier when he could sing them himself. When he came on to the stage at his concert evenings, one could not get him off the stage.

He was na´ve, like a child. His kindness was actually shockingly exploited. His songs were sung at concerts, and were inserted and sung in various operettas, but he earned nothing from them. Boris Tomashevsky, as well as other actors, would take his songs from him and - - - when his friends told him that he should not give his work away so freely, he answered with his good-natured smile: - what will be, what will be ….

He believed everyone and could not imagine that he was being exploited. Before the First World War, he was in the United States and returned disappointed. However, in his conversations with his friends about America, he still said: - perhaps it is my fault; perhaps I am not suited to America …

During the last war, Shternheim spent time in Rzeszow, his hometown. He threw all his energy into social work and was head of various aid institutions. He was one of the founders of the children's home where he spent most of his day with the children teaching them his songs. Also in the ghetto, he was a great optimist and comforted everyone, saying that “It will happen … Hitler must have an ugly end” ….

Nachum Shternheim, the folk-troubadour of Rzeszow, was right: Hitler had an ugly end, but he, Nachum, with his family and with all his Sorrelles and Shlaymelles, unfortunately did not live to see it. He was killed by the German murderers at the age of 50 plus years.

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Rzeszów, Poland

Rzeszów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 20 Jul 2025 by JH