|

|

|

[Pages 421-422]

by Tzvi [Cwi] Karl

Translated by Myra Yael Ecker

Edited by Dr. Rafael R. Manory

1.

The religious life of the Jews of Lwów was on the whole no different from that in the rest of the Lands of Poland and Germany, where Mediæval ways of life and customs still persisted.

Lwów's community was led by rabbis who were known as Av Beth–Din [Head of Rabbinical Court], or by Heads of Yeshivah who did not carry the title Av Beth–Din, such as Rabbi Jozue Falk [Kohn], author of Sefer Me'irat Einayim. From 1680 till 1780, two rabbis concurrently served Lwów as Heads of the Rabbinical Court. One within the town, the other outside it. Likewise, two teaching instructors called Maggidim [religious, itinerant preachers] were also appointed, one within the town, the other outside it, each of them acted as Head of the Rabbinical Court in his area, and both were subject to the authority of the overall Head of the Rabbinical court. Among the Maggidim outside the town were Rabbi Majer Teomim and his son Rabbi Jozef Teomim, author of Peri Megadim [Precious Fruit]. The custom of appointing Maggidim continued till 1859. When the Maggid Rabbi Symcha Natan Öhlenberg passed away, the community leaders decided not to appoint a Maggid outside the town. Instead, the head of the rabbinical court would sit outside the town and a single Maggid together with the rabbinical court would sit within the town.

At first, the authority of the rabbi of Lwów's Beth–Din within the town extended throughout the entire Land, and all the rabbis of the Land [of Reissen; Ruthenia] were under his supervision. Later on, the leaders of the Council of Four Lands split up the Land into two. One part remained under the authority of Lwów's town rabbi, who added to his signature: “Installed within the holy community of Lwów and the Land”, for the town's second part a special rabbi was appointed, who was given the title “Head of the Beth–Din of the Land of Lwów” and he added to his signature “Installed in the Land of Lwów”.

From the rules that set the rabbis' conditions, the following is worth noting: “The Land–Rabbis and the town–Rabbis are granted an apartment and a salary; the former ten Gulden a week and the latter eight Gulden. Every rabbi can accommodate on his premises one married son or a daughter with her husband. The Rabbi himself is exempt from all taxes, be they to the community or to the government, whether fixed or temporary. If a Rabbi or Rabbis conduct[s] any business, they are only liable to the Berdonn tax, and if there is a partner in that business, he has to pay from his share all the taxes levied on him as a community member. The Rabbi's married son or son–in–law, who is supported by him, are exempt, for three years after their marriage, from all taxes apart from the Berdonn due from the dowry. None of the Rabbi's relatives, as distant as great–great–grandchildren and those married to them, are permitted to apply for any honorary post on the community–committee or in the rabbinical court [Beth–Din].

“The communities' and Land's rabbis have to deliver a sermon twice a year (on Shabbat Hagadol and Shabbat T'shuva) for a fee: the community rabbi two Thalers from the community–committee, and the Land's rabbi five Thalers from the Land's committee.

“The Rabbi will receive one Gulden and 15 Groschen for every 100 Gulden dowry, from every wedding in the community; and four Gulden for every divorce [Gett]. The Rabbi and the [religious] judges will receive equal pay for the hearing, and for the certificate and signature–four Gulden.

“Apart from his regular income the rabbi will receive no other income for his incumbency, and he is not permitted to accept any presents from members of his community. The meal for guests following his sermons, is at his expense.

“The rabbi must be honourable, must conduct honest elections in the community and in particular he must oversee that the elections of the shamayim [community treasurers] be fair,[1] and he will himself swear in, individually, each and every shamay.

“For court hearings between the community–committee and one of its members or a member of another community, the rabbi receives no pay. The rabbi must forbid the eating of any meat slaughtered outside the community. As head of the rabbinical court he is not authorised to allow anyone to pay his debt on a home or plot, so long as the man has not [text missing]”

In respect of granting the titles Chaver [Friend] and Morenu [our Teacher], with which the rabbis

[Pages 423-424]

used to honour individuals, and the granting of such honours provided them with a source of income; the rabbis' regulations limited the annual number of honours they were entitled to grant: four titles of Chaver and two titles of Morenu; the title Chaver” was granted to individuals who had been married for more than three years, and the title Morenu, to those married for over six years. Over time, the rabbi could no longer grant titles to an individual, except on production of a certificate showing that he had paid into the community coffers the set amount demanded for such honours. The restrictions set for the communities' rabbis also applied to the Lands' rabbis.

The rabbi was entitled to excommunicate any offender in the community, subject to the elders' views and instruction. There were incidents in which a Land's rabbi intervened in a Land not under his jurisdiction. Such incidents led to disputes and to reciprocal boycotts. To safeguard against such incidents, King Sigismunt [Zygmunt] August issued in 1551 an order, on pain of heavy financial penalties, forbidding the interference of those from one Land in matters outside their own Land, or a Rabbi calling for a boycott in a Land not under his jurisdiction. It was however possible to impose a preventative boycott; in case a person were to violate an obligation he could be subject to excommunication. At times the government took advantage of the Jews' boycott: when it wanted to impose payment on an individual who refused to comply, it then ordered the rabbi to excommunicate the individual.

The community rabbi was elected in the following manner: the community elders congregated and from among the highest tax payers to the community coffers they selected some [religious] scholars, and the latter, by majority vote, elected the rabbi. The manner of electing the Land's rabbi is not detailed in source records.

The number of rabbinical judges [dayanim] at Lwów was 12 inside the town, and 12 outside the town.

When the Austrians first ruled Galicia, a single rabbi was elected, in accordance with the Jewish regulation, for the entire region of Galicia and Lodomeria, and the Land of Zamość together with 12 community–elders and leaders (Judendirektion) managed all Jewish matters in the Land and the region. They acted as a kind of governmental consistory. In disputes between individuals and in questions of inheritance, the Land's dayanim acted in accordance with the Torah. In religious matters they had the authority to excommunicate the offender and separate him from the community and also to punish him by placing an iron yoke around his neck or placing him in jail. The rabbis' verdict, on financial issues, was not open to appeals. The sole option open was to submit a request to the Kaiser's court and to the upper legal department, the rabbinical judges would sanction the judgement by a seal stamped with a two–headed eagle and all other symbols of the Royal House.

The rabbi's election was in two stages: arbitrators were elected from among the Land's people, and the arbitrators elected the rabbi by majority vote. Three candidates were required, and were the votes even, then the decision was left to the Kaiser.

The fixed salary of the Land's rabbi amounted to 600 silver Florins. In addition, it was decided that any rabbi, cantor, [ritual] slaughterer, preacher and teacher of Jewish law at any of the Land's towns, would not be appointed without the authorisation of the Land's rabbi, who received a payment for granting the permission and the certificate. Moreover, the right to honour [an individual] with the title Morenu was granted to the Land's Rabbi alone, which formed a source of income for him.

The 7th May 1789 Jewish statute of Kaiser Joseph II, ruled that rabbis needed to be appointed just for the Lands (Kreisrabbiner), in towns only cantors (Schul–sänger) had to be assigned. The rabbi had no authority over the Jews in legal matters, and he was not permitted to excommunicate other than when so instructed by the authorities. Six years after the unveiling of the Jewish statute (Toleranzedikt), secular secondary–school level examination certificates were required from rabbis. Over and above such a certificate, a certificate demonstrating knowledge of the principles of religion in accordance with the official text (Bne–Zion by Herz Homberg) was in fact also required. The rabbi would be elected by the members of the community entitled to vote, depending on payments of the candle–tax – (seven candles in Lwów) – during the year prior to the elections. At Lwów the district–rabbi was paid an annual salary of 400 Florins from the community purse. Following the 1836 government order, the rabbinical candidate was required to present proof he had passed an Austrian University examination in philosophy and ethics. On the whole, no candidate for the rabbinate had such proof. In 1855, the Charedim managed to convince the Minister Graf [von] Thun to waive this requirement, and he provided certificates for candidates to the rabbinate, exempting them from this requirement. Due to such certificates, Rabbi Józef Saul Natansohn was appointed in Lwów, as did others who followed him.

During the peak of the conflict between the Chassidim and the opposers, Lwów's rabbis played a significant role. Rabbi Hirsz Rosanes (1787–1806), imposed a boycott on the Chassidim, forbidding to employ Chassidim as replacement slaughterers

[Pages 425-426]

and the Chassidim were forbidden from setting up prayer houses and from following their unique version of prayer. During the days of Rabbi Jakub Meszulam [Ornstein], author of Jeschies Jacow [Yeshu'ot Ja'akov] (1805–1839), opposition to the Chassidim had waned however. At that time, the Chassidim reverted from the path of resistance to the Talmud and set regular times for the Talmud and were known as Chadaszim [New]. The name Kloyz Chadaszim [house of worship of the New] was given to the synagogue that the Chassid Jakob Glanzer [Jankiel Jancer] constructed on the site of Saint Theodore's church, Lwów.

|

|

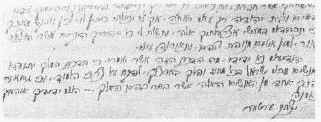

| Handwriting of [Dr.] I. Erter |

Rabbi Jakub fought the representatives of the Haskala [Enlightenment] with greater vigour, and in 1816 he excommunicated SHIR [Salomon Jehudah Rappoport], Erter and others who were considered the disseminators of the Haskala. Subsequently, the authorities obliged him to revoke the excommunication in public.

|

|

| Handwriting of SHIR |

The period after the demise of Rabbi Jakub Meszulam Ornstein, was filled with conflict and controversy between the Charedim and the Enlightened [Maskilim].

As the conflict escalated, one of the community leaders, Natan Sokal, in an attempt of reconciliation, held a consultation at his home to which he invited moderate Charedim. No compromise was reached however, because the Charedim insisted that Rabbi Abraham Kohn relinquish his post. Not wishing to show any sign of surrender, the progressives did not let Rabbi Kohn leave Lwów.

During the funeral of Modal, the cantor of the synagogue outside the town, a severe clash erupted at the cemetery when the Temple's cantor, Ozjasz Abras, attempted to deliver a eulogy for the deceased. Beaten and wounded the people escaped the cemetery; even the “National Guard” had to get involved to bring the conflict to an end. The dispute was also published in the Jewish press outside Galicia, such as the Leipzig Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums, and the Vienna Central–Organ [für Glaubensfreiheit, Geschichte und Literatur der Juden]. The dispute ended with the poisoning of Rabbi Abraham Kohn, his daughter and son on 6th September 1848 (by one of the fanatics, Berl Pilpel).

After the tragedy, Rabbi Symcha Natan Öhlenberg served as the acting rabbi for the Charedim. The Charedim feared to have a rabbi appointed from among the progressives, and were stumped by the 1836 decree that obliged a candidate to the rabbinate to provide proof he had passed the university examination. Rabbi Hirsz Chajes at Zólkiew was the sole candidate to the Galician rabbinate who had passed this examination. Only later was Rabbi Józef Saul Natansohn appointed (1857), (the son of Rabbi Leibusz of Brzeżany [Brezhan], author of the book Bet El [House of God], and son–in–law of Isaak Aron Ettinger of Lwów). Rabbi Józef Saul wrote many books, and it was he who had sanctioned the baking of matzot in a machine [a recently invented machine], contrary to the view of others. The relationship between Rabbi Józef Saul and the preachers at the “Temple of the Enlightened”, Dr. Schwabacher and Dr. Lõwenstein, was amicable.

In 1861, the Kaiser approved the founding of a Rabbinical seminary at Lwów, and granted it official rights. The Kaiser

[Pages 427-428]

also determined that candidates for the rabbinate would not be required to provide proof of gymnasium education or studies in philosophy, but solely proof of knowledge of specific subjects. The Charedim objected to the establishment of the Rabbinical seminary and took steps to thwart its execution. They were successful and the seminary did not open, even after 1907 when its opening was approved by the Galician Sejm.

In the sixties [1860s] Lwów's Charedim submitted appeals to the Ministry, requesting to penalise Jews whose shops were open on the Sabbath or on religious Holidays, and further, that the right to elect the community committees be granted solely to Jews who upheld all the laws noted in the Shulchan Aruch [an abbreviated form of the Jewish ritual law]. The Ministry investigated the issue and came to no conclusions.

Rabbi Józef Saul Natansohn died in 1875, and at the head of the rabbinate was Rabbi Tzvi [Cwi] Hirsz Ornstein, the ardent opponent of Rabbi Kohn.

In 1882, a gathering of rabbis took place at Lwów, that was also attended by Rabbi Szymon Sofer [Schreiber] of Kraków (son of Rabbi Moses Sofer [Schreiber], author of Chatam Sofer [Scribe's Seal]). At the meeting, the Charedim decided on a plan to withdraw the voting rights from a Jew who did not adhere to the laws of Shulchan Aruch. Notwithstanding, he would be obliged to pay taxes to the community coffers. Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi] Ornstein objected however to the plan and left the gathering. Concurrently, the weekly magazine Machsike Hadas [Zeitung für das wahre Orthodoxische Judenthum; Upholders of the Faith] made its first appearance.

Of his reservations about the rabbis' gathering, Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi] Ornstein wrote to Rabbi Meszulam HaLevi Horowitz, the Rabbi of Stanislawów, in the following letter:

“With God's help, Lwów, Sunday Shavuot [the Festival of Weeks, celebrating the Giving of the Torah, seven Weeks after Passover] eve, 1882.

To the all knowledge and my fervent comrade, the outstanding, renowned great scholar, the sage who acquired wisdom in Israel, great is the name of my teacher, Meszulam HaLevi Horowitz, light of the Jewish People, Head of the Beth–Din of Stanislawów and its quarters, May the Lord's grace be on him.

After wishing well to him, whose honourable teaching is like law, a great man may the like of him multiply in Israel, his dearest letter has reached me on time, in reply I herewith express to the honourable teacher that I withdrew without intervening in matters concerning Machsike Hadas, after noting during the Rabbis' assembly of last year, that they would not listen to a whispering voice and directness, but they persisted and I called after them, destroyers and wreckers you will beget destroyers, called destroyers on purpose and wreckers are those who wreck everything, mindlessly. Their common ground to go and harm as experience has taught me, and they still hold on to their stupidity, let them have whatever they have and innocently I go, that is what I found to respond to his honoured teaching and will remain a kin who blesses him with the joy of Yom Tov [Jewish Holy day], his admirer who esteems his merit, the Rabbi Cwi Hirsz Ornstein”.

Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi] Hirsz Ornstein was succeeded, as Lwów's Head of the Rabbinical Court, by Rabbi Isaak Aron Ettinger. He did not subscribe to the views of Rabbi Józef Saul Natansohn, who held that Lwów could be considered “private–domain,” where one could carry items from place to place on the Sabbath. And consequently he lobbied to have fixed Eruvs [wires that form the physical boundary of an urban space within which the Orthodox can carry items on the Sabbath & Holidays] installed in the town, to allow supervising the integrity of the wires and the Eruvs.

Rabbi Isaak Aron Ettinger did not live long; and died in 1891.

Rabbi Izak Schmelkes of Przemyśl was appointed his successor. During his tenure the Governorship approved the new regulations for the community that determined to have two rabbis for Lwów: a community–rabbi for the Charedim and a community–rabbi for the progressives. According to the regulations, 30 voters were appointed who, together with the managers of the “Temple” and members of the community committee, elected Dr. Jecheskiel Caro as community–Rabbi (39 votes, against 15), on 25th May 1898. The Charedim submitted a petition against this selection. Among the Charedim signatory to the petition were Nachum Burstin, Mendel Margoszes, Lejzor Gutwirt and others. The Governorship rejected the petition. On 1st January 1898, the swearing–in ceremony of the community's three rabbis took place: Rabbi Izak Schmelkes, Rabbi Halpern and Rabbi Dr. Caro.

After the demise of Rabbi Izak Schmelkes, Rabbi Leib Braude, the son–in–law of Rabbi Hirsz Ornstein who had been preacher within the town, was appointed Rabbi for the community's Charedim. The relation between the progressives and the Charedim improved, as they too realised the need for knowledge of secular studies. Many of the Charedim provided their sons and daughters also with a secular education. Indeed, when the question arose about nominating Rabbi Leib Braude to the rabbinate, many objected to his nomination, and when he was elected they showed their objection by bringing to Lwów Rabbi Mojzesz Rappoport[2] from America, and received him as the town's Rabbi. His flock concentrated largely at the Chadaszim synagogue.

[Pages 429-430]

The Chibat Zion Movement [Affection for Zion] that sprang up in Galicia, started to make waves and even permeated the Charedim circles. The Charedim at Lwów founded the society Dorsze Szlom Zion which was later renamed Tikwat Zion [The Hope of Zion].

The national movement led the Charedim to collaborate with the progressives, while notwithstanding, the relations between some of the Charedim and the progressives had improved. HaMizrachi Union, formed from the ranks of the Zionists with the aim of cooperating with all circles, and with the Progressives in particular on matters of non–religious nature, rejected a section of the Charedim who found fault in all contact with the Progressives, which led to the formation of Agudas Yisroel (in Congress Poland, the association was known as Shlomey Emuney Yisroel [Stalwarts of the Jewish Faith]), that also operated in Lwów. However, Agudas Yisroel did not encompass all those Charedim who did not cooperate with Lwów's Zionists. Those who did not join Agudas Yisroel were largely the Belz–Chassidim who congregated around the [Kloyz] Chadaszim. The Achdus Yisroel Association also had a presence in the town. During the twenties, the appointed community–committee was made up of the assimilated, the Zionists, as well as representatives of HaMizrachi and Agudas Yisroel. Concurrently, the society Machsikey Limmud was founded, which offered evening classes in Judaism.

1.

In the 1830s, Joseph Perl of Tarnopol spurred Lwów's intelligentsia to emulate, in their town his Tarnopol undertakings in the field of education and in improving religious life. This concept did not however come into fruition before 1840, when two advocate, Dr. Emanuel Blumenfeld and Dr. Leo Kolischer had decided to get involved in the creation of a prayer house for the Progressives, in Lwów. They approached Dr. Jakob Rappaport[3] with the request that he join them to turn their idea into reality, and sign with them an invitation to the Yeshivah to discuss the undertaking. Dr. Rappaport consented to their request, and a meeting was held at Dr. Emanuel Blumenfeld's home on 4th October 1840. Among the invited were: Dr. Moritz Rappoport, a German poet and relative of SHIR; Dr. Natkis, the son of Rabbi Benjamin Cwi [Zvi] Hirsz Natkis, member of the Maskilim [Enlightened] group, whom Rabbi Jakub Meszulam Ornstein had boycotted; Dr. Maksymilian Landesberger who later became a delegate to the Galician Sejm; his son–in–law Dr. J. Rappoport; Dr. Oswald Menkes; Keller; Dr. Adam Barach–Rappoport; the meeting was also attended by Majer Rachmiel Miezes, and his son–in–law Samuel Kellerman and his brother–in–law Meier Münz and others. The issues debated at the meeting were:

After the meeting they began collecting funds, and when they reached 4,000 Gulden they decided to elect a construction committee and to inaugurate the

[Pages 431-432]

“Temple of the Enlightened” in a great ceremony. At the meeting held in Dr. Blumenfeld's home, in October 1840, Dr. Jakub Rappoport delivered a speech, saying: “Today, with the Lord's workings, we inaugurate a Temple and we have to be mindful that most of our brethren who are unable, or are still unwilling to attend this Temple, should not turn against us. That will certainly happen were we not to use the old, Hebrew language but rather use German in our prayers, and we would provoke the anger of the Charedim were we to omit some of the prayers. We need not be ashamed of our nationalism. As a man involved with people, I assert that the peoples do not hate us as much as some of us claim. Furthermore, we need not be ashamed of our religious practices, be it the language or the ritual. There is however a section of the Holidays' prayers that can easily be omitted, as the Chassidim have already done (i.e. liturgical poems). Nevertheless, the basic prayers must be maintained. Personally, for as long as there is breath in me, I shall resist any adulteration of the prayer sequence, or the inclusion of prayers in the German language. I fear however that after my death you will be prepared to do so, for that reason I implore you and make you take an oath that you will not do so.” Some of those who heard the address shed tears, but all rose as one from their seats and took the oath to remain faithful to the traditional synagogue, without any alterations to the language or the religious practice in the new prayer–house. After every detail of their sworn commitment was entered in the minutes, they elected Dr. Jakub Rappoport as chairman of the “Temple's” committee. He was succeeded by his son–in–law Dr. Adam Barach–Rappoport. Donations kept coming, and the fund–collectors did not avoid the doors of the Charedim, and one of them, Jakob Glanzer, a wealthy Chassid, donated 60 Gulden. On the whole, the donations trickled in slowly, and it took a long time before the vision could be materialised.

1842 saw a marked change in the political status of Lwów's community. Initially the authorities did not involve themselves in the conflicts between the Charedim and the progressives, but suddenly they sided with the progressives, delayed the elections that were due and introduced a “supervising committee” in lieu of the elected community committee. Nearly all the supervisors were from among the progressive circles.

The appointment of the commission also advanced the actual construction of the “Temple”. In June 1842, a planning application was submitted to the authorities for the construction of a modern prayer–house, like the synagogues of Vienna and Prague, to which a school for Jewish youth would be attached. The authorities demanded from the applicants to justify the need for such a prayer–house, and to supply information about the financing of its construction and maintenance. The founders replied that the intelligentsia found the old synagogues unsatisfactory, because the prayer in them was loud, they had no preacher and offered no moral instruction, no cantor and no choir to sweeten the prayer for the youth to commune with their God. Also, because all the seats in Lwów's synagogues were sold in perpetuity, it was impossible to obtain additional seats in them. It was also impossible to hold

|

|

| Committee of the “Temple of the Enlightened” (1910) |

[Pages 433-434]

|

|

| “The Temple of the Enlightened” |

in them patriotic parties, and this adversely affected the youth's education. In respect of the finance, they mentioned the 4,000 Gulden legacy left by Isak Rosenberg for the purpose of constructing a new prayer–house. A positive reply was received from the authorities and the only question was where to erect the prayer–house. After an extensive debate they chose a site on Rybia Street that they had purchased from Lwów's municipality for 1,434 Gulden. The land was entered at the land–registry office under the title “Deutsch–Israelitisches Bethaus [German–Jewish prayer–house]”. At the end of the 19th century, its name was revised to “Synagoga postępowa” (Synagogue of the Progressives).

Among the donors to the appeal was Graf Saryusz Zamojski, who donated a large number of trees, and Kaiser Franz–Joseph I's father donated 100 Gulden, and these facts were published in all the newspapers.

The construction of the “Temple” began to the discontent of the Charedim. It is said that at the beginning whatever was built during the daytime was demolished at night by unknowns, so that guards had to be posted to protect the construction from being destroyed. The building plan emulated that of the prayer–house on Seitenstettengasse, Vienna (as noted by Dr. Balaban in his book: Historia Lwowskiej synagogi Postępowej [History of the Lwów's Progressive Synagogue]. As a child I heard told that the building was constructed according to a plan that followed the template of the cross of the Catholic Church, and that only later by adding buildings on the sides of the edifice, the form of the cross was disguised.). While the building was under construction, those engaged in its undertaking turned their attention to inviting those who might officiate in it. For the post of cantor, the proposal of Ozjasz Abras of Tarnopol was accepted. It was harder to find a preacher. On the advice of cantor Sulzer of Vienna, Dr. Emanuel Blumenfeld approached Rabbi Abraham Kohn, who was rabbi at Hohenems, Vorarlberg (Austria) and invited him to come and deliver two trial sermons at Lwów, and promised to pay his travel expenses.

Rabbi Abraham Kohn was born at Zalužany [Saluschean], Jungbunzlau district of Bohemia. His father, Salomon Kohn, was a pedlar. The son studied the Bible [Tanach] and Talmud with great interest. At the age of twelve he moved to Jungbunzlau where he concluded his humanistic education, and concurrently studied Talmud with Rabbi Izak Spitz. He was employed by a wealthy Jew, but was dismissed after being caught reading a French book. He moved to Pisek and earned his living as a private teacher. It was here that he delivered his first sermon at the inauguration of the new prayer–house. He spent some time in Prague and befriended Rabbi Samuel Landau, who furnished him with a teaching permit. Rabbi Samuel Kauders at Kaladay, Hungary, also granted him an ordination certificate. Herz Homberg granted him a pedagogical certificate for teaching [the Jewish] religion. In 1833, he was given the post of Rabbi at Hohenems; he taught at two schools: the German school and the religious school where he was headmaster, taught religion and the Hebrew language. At the prayer–house he introduced some reforms: he shortened the prayer, introduced a choir, introduced the calling to the Torah by the use of first name and surname, and on Simchat Torah calling just nine individuals to the Torah.

[Pages 435-436]

Apart from these functions he also founded societies, “Gemilus–Chesed” and others. His sermons were published in print and he contributed to various magazines and published a book on the grammar of the Hebrew language.

Rabbi Kohn was asked to serve as preacher in Lwów. He delivered his sermon at the Synagogue outside the town, on the Sabbath of the weekly Torah portion (Parashat) Ekev. The progressives who congregated in the Synagogue, listened to the preacher's words with satisfaction, and did not wait

|

||||

Register from 1840 created by the Committee for the Construction of the Progressive Synagogue at Lwów] |

||||

for his second sermon, but immediately made a contract with him and submitted it to the authorities for their approval, and the approval was received.

According to the contract, he was given the post of instructor of religion (religionsweiser) and he was obligated to officiate as preacher at the yet to be constructed “Temple”, wearing the official preacher's garments that were decided for him. Once the question of the religious instruction was set, he would be entrusted the teaching of [the Jewish] religion at gymnasiums [secondary schools] and at the state school planned to be built locally, at which he would become headmaster and would oversee the religious instruction. Were he not to be granted the authorities' licence as instructor of religion, he was promised the Lwów's rabbinate with all its privileges and duties. Rabbi Kohn returned to Hohenems, resigned his post there, returned to Lwów and reached it on 5th May 1844.

His first sermon on the first Shabbath after his arrival at Lwów to officiate as preacher, was also delivered at the synagogue outside the town, in the presence of the Jewish intelligentsia and the government representative, [Franz] Ferdinand Archduke of Austria–Este, the regional Head, von Millbacher, and the Mayor Festenburg with his entourage. Rabbi Kohn wore a preacher's attire. The following day, according to the Rabbi's brother, the Orthodox tore their clothes over the desecration of the holy building with quotes from the Bible, in German. To enrage the Charedim's even further, an anonymous writer told in “Mefer Ezat Reshaim [Breach the advice of the wicked”], that during the prayer the “Parochet” [ornamental curtain in front of the holy ark in a synagogue] was placed on the floor and Rabbi Kohn stepped on it. Once the general school opened, Kohn became its headmaster.

In 1844, the cantor Ozjasz Abras of Tarnopol who took on himself the task to form a choir at “the Temple” and train its members in their roles, was also engaged. Abras who was born at Brody, studied to be a cantor while serving as assistant to Cantor Model, at the

[Pages 437-438]

synagogue outside the town, as well as with Cantor Bezalel of Odessa. He also studied with Sulzer, and according to him even with Liszt. During 1842–1860 he was cantor at the Tarnopol “Temple” founded by Josef Perl. Being unsuccessful in training the choir, the Italian Józef Ernesti, and the German Pollak, were brought in to assist him, and to train the choir. Michał Wolf was appointed reader of the Torah at the synagogue. The first caretakers of the “Temple” were Juda Samuel Kantor and Salomon Blumenfeld. On Friday 18th September 1846, the inauguration of “The Temple of the Enlightened” was celebrated in the presence of the government representatives and under the protection of the armed forces. Rabbi Abraham Kohn gave his address after the opening words of Dr. Blumenfeld.

Abraham Kohn held the title of “Instructor of religion and preacher” (Religionsweiser und Prediger), but he aspired to be Lwów's Rabbi, replacing the author of Jeschies Jacow, Jakob Ornstein, who died in 1839. The issue was in the hands of the authorities, and once the Charedim heard of it, they submitted an objection to the authorities, describing Abraham Kohn as a peasant and an outlaw; their protestation was in vain and Kohn was confirmed by the authorities as Lwów's town Rabbi.

In his sermons he strongly criticised the behaviour of the Charedim, and in “Letters from Galicia” which he published in the board of shame; he mocked superstitions and mystery, the custom of Kaparot and the “Tashlich,” as well as women's head shaving and their wearing of wigs, and adornment with jewellery that gave rise to the envy of the gentiles. He also organised “confirmations” (Bar–Mitzva celebrations unlike the traditional custom) for boys and girls, which the Orthodox considered a step towards religious conversion.

After the 1848 March Revolution in Vienna, the Charedim decided to submit a petition to the Kaiser or to the government, to dismiss Abraham Kohn from his post, because he was the cause of all evil, and furthermore to remove from their status the leaders of the progressive community of Lwów and the other towns; it was that which they considered a prerequisite for equal rights. The petition which was signed by a large number of people, reached the community officer Bernard Piepes, who confiscated it, and Grünfeld who had collected the signatures, was jailed and the Charedim's recommendation was opposed. The hot–headed among the crowd surrounded Rabbi Kohn's home, threw stones at its window–panes and tried to force themselves into the house that was closed to them. The army was alerted, and was hard put to disperse the attackers. A consultation of the community leaders and the Charedim ended in deadlock because the Charedim insisted on their demand that Kohn leave Lwów, and they even agreed to provide him with a large compensation, for his livelihood until he found another job. The progressives opposed the condition and the schism between the two sides widened. Ever since then, Rabbi Kohn could not walk the streets in safety. Eventually he was maliciously poisoned to death.

Dr. Moritz Lõwenthal replaced him as rabbi for a short period only, followed by candidates for the post of preacher: Dr. Eleazer [Łazarz] Igel, who studied at the Padua rabbinical seminary directed by SaDaL [Samuel David Luzzatto] and was lecturer at Lwów University; and Dr. Efraim Izrael Blücher. Dr. Igel was originally from Lwów and on his return from Padua he got a post as teacher of religion at the gymnasium and a licence to teach Oriental–languages. Unable to manage as a preacher nor as a University lecturer, however, he left Lwów and became the rabbi of the progressives at Czernowitz. Dr. Blücher also left Lwów. Michał Wolf held the post of preacher at “The Temple of the Enlightened,” first on a temporary basis but he was later permanently appointed.

The “Temple” synagogue managers in those days were Dr. Emil Blumenfeld, Marek Dubs and Hersz Zipper. In 1850, they were succeeded by Kolischer and Ozjasz Jolles, and in 1852, the appointed managers were Izak Aron Rosenstein, Ignac Lewkowicz, Abraham Beiser, Dr. Leo Kolischer and Berisz Hescheles. The managers in 1858, were: Dr. Bernard Sternberg, the advocate Dr. Dawid Diamand, Hilel Lechner (from among the Maskilim circles, and council leader at Zniesienie) and Motel Braun. Lechter was said to occupy himself with the Sabbath laws, in order to know how to transgress them; he was a “Temple” manager for over twenty years.

For years no preacher had replaced Rabbi Abraham Kohn at the “Temple”. The progressives had their eyes on Dr. Leopold Lõw, the Rabbi of the Szeged community in Hugngary, who came to Lwów and delivered a sermon and a scientific lecture at the Temple, and to the community, but was not appointed. In 1857, Dr. Szymon (Leon) Schabacher was appointed preacher. He was born at Obernsdorf, [Baden–]Württemberg, in 1817. He gained rabbinical ordination [S׳michut] and in addition, a doctor of philosophy from the University of Tübingen. He served as preacher in Prague and later as Rabbi and preached at Homburg, Schwerin and Landsberg. When he arrived in Lwów as candidate for the post of preacher at the “Temple”, the community did not take to him because of the arrogance he showed towards them, receiving them dressed in the official clothes. Even to weddings and funerals he arrived in his official clothing, thus provoking the Charedim and probably also the Catholic clergy, on appearing in front of Governor Gułochowski in a garment that enraged him. After a short period he left for Odessa where he was appointed community Rabbi and preacher (1859). In that capacity he served there for 25 years. When elections to the Odessa rabbinate were held in accordance with Czar Alexander III's orders,

[Pages 439-440]

however, Dr. Schwabacher was unsuccessful, and aged seventy he was left without an income. He died on 25th December 1888 [10 Tevet 5648].

Together with Dr. Schwabacher, the cantor Abras also left Lwów for Odessa, where he had been accepted as cantor.

Sixteen candidates vied for the post of preacher for the Lwów community, of whom only four had passed the examination: Dr. Duschak, Rabbi at Gaya in Mähren [Kyjov]; Dr. Hajjim Jolowicz, of Kõnigsberg [today Kaliningrad, Russia]; Moritz Hirschfeld, of Gross Meseritsch [VelkTashlich MeziŘíčí]; Bernard (Isachar Berusz) Lõwenstein, Rabbi at Buczowice. Dr. Lõwenstein won the election with a large majority (1862). In addition to his post as preacher, he was also charged with teaching religion at the secondary schools, and managing the population register (births, deaths and marriages). As registrar, the Rabbi of the Charedim required his approval for arranging marriages, an approval that he was not permitted to delay except when the marriage was illegal.

After cantor Abras had left Lwów, his deputy Mojzesz Roman replaced him and only in 1862 was the scholar and Maskil Oswald Weiss of Szeged appointed cantor. Dr. Lõwenstein and the cantor Weiss managed to gain the favour of the praying public at the “Temple”. Dr. Lõwenstein who was born at Międzyrezc [Podlaski] in 1821, was a scion of the Rabbi who wrote Pnei Jehoschua [Yehoshua], and was related to the families Herc Bernstein and Horowitz. He studied in Amsterdam and Hanover (at the Yeshivah of Rabbi Natan Adler, who later became a Rabbi in London), at Prague University and with Rabbi SHIR, Jakub Józef Ettinger and others. He was preacher and headmaster of the school at Lipto St. Miklosz and Rabbi at Buczowice, and from there he was invited to Lwów.

Dr. Lõwenstein's sermons aroused much interest, and even non–Jews, among them Governor Mensdorff, came to hear his speeches. He held his sermons on special events such as, on the 70–th anniversary of Lipman [Leopold] Zunz, the eulogy for SaDaL, etc. and further at the 1878 opening of the first congress of Galicia's communities, which was instigated by Szomer Izrael [The Guardian of Israel], and at the congress of the “Fire Brigade” he held prayers at the “Temple”. The prayers on State occasions, were generally accompanied by music played by a military orchestra.

Dr. Lõwenstein often lectured to the “Association for the resourceful the Good and the Honest” (Verein für Bildung und Geselligkeit) and also to the Szomer Izrael society, which for a while formed the hub of political activity.

Dr. Lõwenstein taught religious studies at two gymnasiums and also acted as the prison's preacher. In 1883, together with Szymon Landau, he opened a Talmud–Torah [Torah–Study school] named Ohel Mosze [Moses' Tent] where Jewish and secular studies were taught. This Talmud–Torah lasted only two years because of disputes with the Charedim. Apart from his educational work, he was also much involved in charity and was even elected to the town–council. He received the “Gold Cross for Merit” and in 1885, the Kaiser Franz Joseph I's Medal. He died in 1889. His only son, Natan, married Miriam the daughter of Samuel Horowitz, one of the well–to–do, the community leader and among the leading assimilators.

During his time, the managers of the”Temple” were Dr. Sternberg, Lechner, Leib Russman, the pharmacist Jonas Beiser and the pharmacist Zygmunt Rucker. In 1870, the anniversary of the “Temple” was celebrated in the presence of the Sejm's Christian delegates: Smolka and Ziemiałkowski as well as representatives from the municipality and the armed forces. Dr. Lõwenstein gave a celebratory address and cantor Weiss showed his prowess in musical renditions. At the festive reception that followed, Hilel Lechner also spoke, warning of the culture–war that threatened Lwów's Jewish community at the time. Hilel Lechner was the chairman of the Temple's management, and his colleagues were Jonas Beiser, Emnuel Gall, Zygmunt Rucker, Dr. Szymon Schaff who later became chairman of the community committee. In 1882–3, of the earlier managers [of the Temple] only Lechner and Beiser remained, and new ones were appointed: Dr. Salomon Landesberg, Natan Mayer and Henryk Jolles. Natan Mayer, who joined the community committee after some time, was a member of the chamber of commerce and of the municipality as well as chairman of the “Temple's” management board. Under his management a foot pedal harmonium (Fussharmonium), and later an organ were introduced into the “Temple”. In 1883 there were elections to the management, but most of the elected withdrew from their posts; the community committee then appointed Lechner as management–commissioner, and Dr. Schaff and Dr. Landesberg, his assistants. Shortly afterwards new elections were held and Beiser, Mayer and Landesberg, Emil de–Mieses and Eliasz Zabludowski formed the management.

After the death of Dr. Lõwenstein (March 1889) the preacher's post was offered by tender. Part of the candidates' requirements was the knowledge of German and Polish. Of the candidates, three were invited to the examination: Dr. Szymon Dankowicz, Dr. Herman Klüger and Dr. Jecheskiel Caro. Of the three, Dr. Caro was accepted as preacher and the supervision of religious studies was also given to him. The title of “Rabbi” which he requested to be granted, was declined until the regulations were changed.

Dr. Jecheskiel Caro was born in 1844 at Pniewy where his father, Józef–Chaim was rabbi. His family lineage extended back to Rabbi Józef Caro, author of Shulchan Aruch. Rabbi Józef–Chaim wrote books and was also rabbi at Fordon and Włocławek [Leslau], he contributed to [Nachum] Sokolow's periodical HaAsif [The Harvest] and was a sympathiser of Ahavat Zion [Love of Zion] Movement. His eldest son Jakub was

[Pages 441-442]

a lecturer in general history in Vienna University and was appointed professor at Breslau [Wrocław] University. Dr. Jecheskiel Caro attended the gymnasium at Bydgoszcz [Bromberg], studied at the Breslau rabbinical seminary, as well as philosophy and eastern–sciences at the University. He received his doctoral degree at Heidelberg, was a teacher at Lodz [Łódź] and rabbi to the joint communities of Tczew and Gniew, and [later] at Erfurt. He contributed to Jüdisches Literaturblatt by Dr. Rahmer of Hamburg, and published researches about Jewish studies. In 1882 he was appointed as teacher of religion at Pilsen [Plzeň], and in 1891 he moved to Lwów. In his handwritten submission he noted that he had been a preacher at Lodz, knew Polish but was not fluent in it, as for twenty years he had served the communities of Germany. He looked forward, however, to renewing his knowledge of Polish and that it would be possible for him to deliver sermons and speeches also in this language. His declaration led at first to doubt about his appointment, but his candidacy was accepted nevertheless. This was probably due to the strong recommendation by Rabbi Dr. Jellinek of Vienna.

At the start of the 1891–1900 decade, the “Temple” management consisted of: Beiser, Mayer, Wohlfeld, Emil de–Mieses and Nechemiasz Landes. Mieses and Landes who had resigned, were replaced by Salomon Rosenzweig (formerly a school teacher), Ephraim Appel and Dr. Jakub Diamand (advocate). In 1894, the community–committee's representative, the advocate Dr. Salomon Landesdberger joined the management. The 1898 elections replaced Beiser, Mayer and Rosenzweig by Dr. Adolf Menkes and Jakub Rubinstein. During that decade, the “Temple” building was renovated, an organ was installed in it and even women were admitted to the choir. Prof. Wojnowski (a Christian), was appointed organ player, and it was decided to use it even on the Sabbath and religious Holidays.

Once the authorities had confirmed the new community regulations, elections were held and Dr. Caro was appointed community Rabbi. He was also appointed member of the municipality. To teach religion he prepared a syllabus for school–classes at all level, and a biblical writing for schools, “History of Lwów's Jews” [Geschichte der Juden in Lemberg].

As deputy–preacher, Dr. Samuel Gutmann was appointed to deliver sermons in Polish. Born in 1864 to a poor family, his parents married him young, and when he reached the age of 27 he divorced his wife and went to the gymnasium at Radowce [in Bukowina] and Lwów and passed his matriculation examinations (1893). He went to Vienna where he studied at the rabbinical seminary and gained a doctorate and a rabbinical ordination before returning to Lwów. Here he was appointed prison's preacher as well as headmaster and teacher of religion at the community school. While exercising his undertaking he had the opportunity to deliver sermons to the youth and the worshipers at the “Temple”. With his sermons he tried to inject a Jewish spirit into the education of the youth. The assimilated complained to the national schools' council about the teachers of religion and of Hebrew, and the council issued a ban on the teaching of the Bible in its original form, demanding instead that teachers use the priest Wujek's translation in their teaching. Consequently, in his sermons Dr. Gutmann vigorously voiced the demand to teach the youth to read the Book of Books in its original form, so that they understood the language of the prophets, and that it was necessary to tell the youth the history of its People, its greatness and its glory. In 1905, the community committee confirmed Dr. Gutmann's status and he was appointed preacher in Polish. In time he was released of his duties as school teacher, and Samuel Szlagowski was appointed in his place. Initially, Dr. Gutmann served as “The synagogue's Rabbi”, but in 1920 he was given the title of “Lwów's community Rabbi”. Dr. Lewi Freund was appointed the synagogue's acting Rabbi.

In addition to his roles as community Rabbi, Dr. Gutmann was also tasked with the management of “The Institute of Education for Teachers of the Mosaic Religion”, and the supervision of religious studies, at first at the general and secondary schools. In 1903, he organised together with Prof. Taubes a Jewish–studies course. In due course, Prof. Allerhand, Prof. Schorr, E. M. Lifschütz, Cwi Karl, Gerszon Bader, Dr. Hausner, Dr. Freund, Hendel, Dr. Braude, Dr. Bałaban, Dr. Samuel Rappoport and Dr. Goldstein joined the “course”. In 1905 the [Jewish] “Association of Teachers of Religion” was established and issued the magazine “HaOr [The light]”. Dr. Gutmann was invited to manage its homiletic section.

During 1901–4, Dr. Maksymilian Fried and Jonasz Ehrlich joined the Temple's management board. During 1904–7 Jakub Rochmis replaced Maurycy Wohlfeld. And during 1907–10 Dr. Diamand who had been elected to the community committee, left the management, as did Dr. Fried, while Herman Dattner, Wiktor Mendrochowicz and Leon Hescheles joined. Dr. Menkes who had been elected to the community committee, was replaced by Dr. Wasser as chairman of the board, a post he held during the First World War and later.

In time the “Temple” was too small to contain all members of the intelligentsia who wished to pray there, especially during the High Holidays, so that prayers had to be held at the community–committee's hall, where the cantor was an assistant from among the community officials and the role of preacher was filled by one of the religion–teachers. Some of the intelligentsia prayed at the synagogue of the orphanage, where the cantor was the religion–teacher Wein, and the preacher was Dr. Bałaban. Once the idea to construct a new synagogue for the progressives was mooted, it reverberated around the community with the chair of

[Pages 443-444]

the community committee, Dr. Emil Byk, who was also a delegate to the Austrian parliament, supporting the proposal and taking deliberate steps to see it through. The chosen building plot was in the vicinity of the Sejm, within Kościuszko Park, but the plan was shelved for political reasons. Changes to the “Temple” were however undertaken, the building was extended, electric lighting and gas heating were installed. Its official name “The German–Jewish Prayerhouse” was also changed, to the Polish “Gmina Synagoga postępowa” (The Community's Progressive Synagogue). With Dr. Jakub Diamand's endeavour an archive was established both at the “Temple” and at the “community committee”.

A custom was introduced at the “Temple” to hold a prayer for the youth, at the start and at the end of the academic year, as well as on Polish and Austrian national holidays. On the Festival of Shavuot [Weeks] 5602 (1902) a “festive confirmation” of Jewish girls took place conducted by the religion–teacher from the state school, Natan Schipper. At the ceremony the young girls donated a Parochet they had embroidered themselves. Prayers outside the authorised prayers were also conducted, on the national Polish, Austrian and Jewish Holidays, and on special memorial days, such as the 700–th anniversary of Maimonides's demise, memorial celebrations for Rabbi Saadia Gaon, Rashi, Herzl's memorial, etc.

During Rabbi Dr. Caro's incumbency, the custom of whispered praying was replaced by the cantor praying aloud while the community listened and responded with Amen; furthermore, [the prayers] Yakum Purkan and Av–Harachamim were dropped from the Sabbath service. In 1911, the cantor Halpern left the post and was succeeded by Jehoszua Seitz, cantor at Berdyczów [Berdychiv]. The composition of the last management board of the “Temple” before the outbreak of the First World War, was: chairman, Dr. Wasser; deputy, Jonasz Ehrlich; secretary, Dr. Sofer, deputy secretary, Karol Stand[4]; member “without–portfolio”, Wiktor Mendrochowicz.

With the outbreak of the war in 1914, the “Temple” board members, together with Dr. Caro and members of the community committee, were away from Lwów. Only Dr. Jakub Diamand had remained in town. Dr. Gutmann joined the armed forces as a military rabbi and was sent to Bukovina. Dr. Diamand gave the role of rabbi and preacher to Dr. Hausner. In his role he officially performed marriages for many couples who had no marriage certificate, in order that the wives of those joining the forces would receive the assistance they were due by law.[**]

In November 1914 a temporary “Temple” management board was put together, made up of: Dr. Maurycy Kahane (chairman), Rubin Kroch, Adolf Lindenberger, Prof. Salomon Mandel, Mikołaj Weinreb, Józef Hausmann. Prayers were held as usual and the new management tried to assist the home workers. Despite the quiet and order, the Jews were not oblivious to the fact that special caution was required at such times. There was an instance on 19th December 1914, Tzar Nikolai's birthday, that Jews from Russia who were visiting Lwów on trade business asked Dr. Hauser to hold a festive prayer for the Tzar's wellbeing. Margolin, a Jew from Kiew, offered a large sum to the Temple coffers. The General Governor Bobrinsky also approached Dr. Hausner supporting this request. However, having considered the danger that the Jews of Lwów might face from the Austrian authorities as a consequence, Dr. Hausner refused their request.

On 22nd June 1915, Lwów was liberated from the occupier, and on 28th Dr. Gutmann returned to Lwów and took up his old post. Rabbi Dr. Caro did not return from Vienna and died there, aged 70. Other members of the “Temple” management board who had settled in Vienna during the war, and who died there, were: Jonasz Ehrlich, Herman Dattner and Wiktor Mendrochowicz. The board members who returned to Lwów were: Rochmis, Appel, Aszkenazy, Karol Stand and Dr. Wasser.

The chairman of the community committee, Dr. Diamand, was deported to Russia by the occupying authorities, and Jakub Stroh, who stood in for him, was elderly. The authorities then handed the community committee's management to Emil Parnas and appointed Dr. Wasser as his deputy. Dr.Wasser did not give up his post on the board of the “Temple”, however, and regained all the roles, which he shared with the colleagues who returned to Lwów.

Even before the end of the war, Rabbi Dr. Caro's coffin was dispatched from Vienna to Lwów and Dr. Gutmann delivered a eulogy during his burial.

Homes were searched for weapons, and in one operation a Polish company headed by the officer Łos went to the “Temple” and demanded to search it. Dr. Wasser was informed and he came immediately. When he saw the officer smoking a cigarette, he ordered him to throw it away before entering the house of God. The officer refused and Dr. Wasser blocked the building's entrance with his body and declared: “I shall not permit the desecration of a holy place; you will only enter smoking, over my dead body”. His words made their mark and the officer dropped the cigarette from his mouth and began his search. Dr. Wasser followed him throughout, and when the officer finished his work he arrested Dr. Wasser

[Pages 445-446]

and led him to headquarters. Many accompanied him on the way including Dr. Gutmann. The commissioner at headquarters asked his pardon and expressed his regret over the incident, and the searches in general, and apologised, blaming the state of war for the incident.

It seems that the incident gave rise to an anti–Semitic myth. Some years later, Prof. Jakubski in his book “Defence of Lwów” [Obrona Lwowa] told the following: “On the 23rd (November) –I don't recall the exact time– my room was entered by three strange characters, presumably due to the absence of Mączyńskie [Manczynski]. Two respectable elderly Jews slowly led an old man who could hardly stand on his feet, propping him all the while by his arms. The old man appeared like a biblical figure… I rose in deference and invited the guests to sit down. But the old man said in a whisper: Sir! the “Temple” was destroyed, the holy of holiest place was desecrated. Help!

|

|

| Letter of Rabbi Kohn to his brother, 1848 |

I immediately reached for the telephone and contacted the Cavalry minister, Mączyńskie… and ordered: Sir, let the Cavalry minister immediately send a company under the command of an able officer to the “Temple” to defend it. Let me know immediately the reply, I am waiting on the line. Mączyńskie repeated my order and a company was sent straight away. The three old men waited for the response and I calmed them that order would be restored… A quarter of an hour later the phone rang and Mączyńskie sent a message that is hard to believe: ‘The company sent found the “Temple's” vicinity completely quiet, but assuming that robbers hid inside, it opened the gate and carried out a search, and behind the Parochet, in place of the holy ark, was a machine gun and some boxes with bullet, and more than ten hand grenades’. I was enraged and reproached these distinguished people who tried to secure for themselves an arsenal, by relying on our naivety. ‘Begone, I called, or else I shall order an arrest!’. They immediately vanished into thin air.”

When these words were published in Prof. Jakubski's book, Dr. Wasser wrote in the newspaper Gazeta Poranna an open letter published on 27th February 1933, in which he detailed the facts of the search as carried out by Officer Łos, and its outcome, and he accused Prof. Jakubski of misrepresenting history and instilling hatred in the citizens of one country. Prof. Jakubski's riposte to Dr. Wasser was impolite, but as to the issue itself he tried to backtrack on his statement, when Christian witnesses also confirmed Dr. Wasser's version. As known, the Jews were accused that when the Polish army had marched into Lwów, they showered it with boiling water, from their windows. When Lwów's Jewish delegation, with Dr. Wasser among them, appeared before Piłsudski at Castle Belvedere, he reminded him, by–the–way, of this accusation. The delegation, and Dr.Wasser in particular, protested against his words and declared that it amounted to nothing other than a hoax fabricated by Jew–haters, to cover–up for the pogroms they had inflicted on the Jews in November 1918.

After World War I and the subsequent wars between the Poles and the Ukrainians, and between the Poles and the Russians, the “Temple of the Enlightened” was renovated and the fire damage inflicted on it during the pogroms was repaired.

In 1920, Dr. Lewi Freund was appointed acting Rabbi of the synagogue, to assist Dr. Gutmann in his many roles, and because of his weak health from a disease that he caught.

Dr. Freund was born at Przysietnica in 1920, he received a Cheder education, studied with Rabbi Szulim Gabel at Brzozów, Rabbi Gedalja Schmelkes at Przemyśl and others. In 1903, he graduated

[Pages 447-448]

|

|

| Rabbi Bernard Lõwenstein |

from the national gymnasium at Sanok, and entered the rabbinical seminary in Vienna where he also studied philosophy at the University. After concluding his studies he came to Lwów and was employed as teacher of religion at the gymnasium. During the years 1914–1915 he remained at Lwów and later joined the teaching staff of Lwów's Torah study school for teachers. During 1917–1918 he was a military rabbi with the Austrian army. After the war he returned to Lwów and taught at gymnasiums. When the “Association of primary and secondary schools” was formed in Lwów in 1919, chaired by Prof. MojzTashlichsz Schorr, Dr. Freund joined its committee together with Dr. Tauber, Cwi [Tzvi] Karl and others.

In 1920, the Jewish Pedagogical Institution was founded in Lwów by the “Association of primary and secondary schools”. Prof. Schorr taught Arabic there, while Dr. Freund was involved there too, together with Rabbi Gutmann, Dr. Tauber and Cwi Karl.

|

|

| Dr. Szymon Schaff |

In 1921 Dr. Freund was given the title “The Synagogue's Rabbi”, and in 1928 he was elected the community–Rabbi. Apart from the rabbinical function he was also tasked with the supervision of religious study at the state and the secondary schools. When Prof. Schorr left Lwów and was appointed rabbi at Warsaw, Dr. Freund took over the post of headmaster of the Pedagogical Institution; in 1943, Cwi Karl took over this role.

During the Shavuot Holiday of 1925, a celebration was held in honour of Dr. Gutmann's work for the past half–jubilee. The “Temple” management–board consisted of Prof. Schorr, Karol Stand, Józef Hausmann, Jakub Mund, Izak Melzer and others.

The rabbinical post underwent change too. Rabbi Dr. Gutmann fell ill, and Dr. Freund replaced him. The work was so extensive that a second rabbi was required to share the load. Dr. Jecheskiel Lewin (son of Rabbi Natan Lewin, and grandson of Rabbi Izak Schmelkes) was then appointed to the role.

Dr. Jecheskiel Lewin was born at Rohatyn in 1897,

|

|

| Dr. Ozjasz Wasser |

he concluded his gymnasium schooling at Rzeszów [Resche] and studied history, philology and philosophy at Kraków University. He received his doctorate in philosophy as well as a teaching certificate from Rabbi Pinkas Dembitzer and the Rabbis of Brody and Tarnopol. He was appointed rabbi at Katowice, and was later invited to serve in Lwów (1928). Besides his role of rabbi, he was also tasked with the supervision of religious studies at the state schools, and he was also part of the Jewish Pedagogical Institution.

These roles did not suffice for Rabbi Lewin, and he was also drawn to political and Zionist involvement. He was even appointed as delegate to the Zionist Congress, and as president of the Keren Kayemet LeIsrael [Jewish National Fund] for Eastern Galicia.

At the request of Dr. Lewin, it was decided to play the organ only during the prayers on the three High Holidays [Regalim] and on Friday evening prayer up to Barchu.

In 1934 and 1936, Jubilee celebrations were held at the “Temple” for Dr. Ozjasz Wasser, chairman of the management; on the 20–th anniversary of his service, and on his 70–th birthday.

In 1935, Rabbi Dr. Gutmann died and his collected sermons were published by a group of friends.

On the outbreak of the WWII and the occupation of [Eastern] Poland by the Russians, religious studies were prohibited at Lwów's schools and the rabbis were forced to officiate in Yiddish. Rabbi Dr. Freund died (1941) during the Russian rule. In town, Dr. Lewin was left, and he regarded his role as a mission; he gathered large crowds at the “Temple” and refused to renounce his position as Rabbi

[Pages 449-450]

|

|

|

|

|||||||

despite offers from the authorities of important posts in the public and scientific fields.

On 30th June 1941, the first Nazi battalions marched into Lwów. The following day the Ukrainians rampaged and attacked the Jews. Friends of Dr. Lewin asked him to hide from the peril, but he was determined to approach the Metropolitan [Greek Catholic Archbishop] Sheptytsky and ask him to influence the Ukrainians to stop the massacre. Dr. Lewin composed an address to the Metropolitan that his son Isaac translated into Ukrainian. He put on his rabbinical garment and the black gloves that he wore solely to funerals, and walked to the Metropolitan's Palace. The latter asked him to stay at his Palace till the riot had subsided. Rabbi Dr. Lewin replied: “My mission is over. I came to ask on behalf of the community, and I return to the community where I belong, and may God be with me”, then he left the Palace.

His son Izak describes his death in the following words:

“At that moment, there was a Ukrainian militia in our house that dragged Jews to Brygidki (the large jail on Kazimierowska Street), one of our neighbours waited specially to warn my father, but he said to her: “All the same.” And white as a sheet he climbed the stairs. Near the door of our apartment the Ukrainians got hold of him and marched him to Brygidki, where he died a martyr to God. Beaten by Germans and Ukrainians, he walked proud, his head held high and his expression peaceful, the face of a man whose mission had been discharged and whose conscience was singularly pure. When he came among the many Jews in the jail, he recited the prayer prior to death and turned to his co–sufferers and in a loud voice called out: “Sh'ma Israel, Adonai…” and did not finish his words as a machine gun put an end to his words and his life”.[5]

Thousands of Lwów's Jews were murdered together with him, and the “Temple” was totally destroyed by the Nazis.

Notes: All notes in square brackets [ ] were made by the translator or by the editor.

[The spelling of names was mainly derived from publications by Dr. M. Balaban, other names/titles were added as they were spelt in Lwów at the time.]

Original footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lviv, Ukraine

Lviv, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 14 Mar 2023 by LA