|

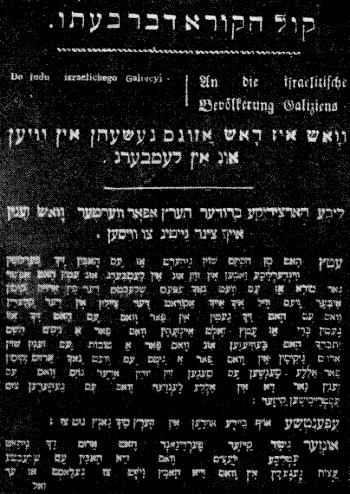

[a flyer in Yiddish; warning call about the current plight]

|

|

[Pages 303-304]

Translated by Myra Yael Ecker

Edited by Dr. Rafael R. Manory

| The standing of Lwów's Jews in the economy, in trade and in industry. The Jews within the general education system. The academic intelligentsia's involvement in the community's life. The 1868 community elections . The Szomer Izrael Association and its activities. Dr. Bernard Goldman and his drive toward Polonisation. The Jews and the Poles after the 1863 uprising. The 1874 municipal elections. The preacher Bernard Löwenstein. The 1878 communities' gathering and the resistance of the Orthodox. The community committee during 1883–1888. 1890 referendum. The Machsike HaDas Association. The Orthodox's struggle with the conduct at the “Temple.” The 1890 parliamentary law of communities' regulation. The beginnings of the Zionist movement. Seminary for teachers of religion. The educational institutions. The beginnings of the workers' movement. Democratisation of the community and its institutions. At the outset of World War I. Lwów's occupation by Russia's armed forces. The Russian authorities' attitude towards the Jews. Vaad HaHazala. Collaboration with the “Committee of Russian Jews.” Return of the Austrian armed forces. The resumption of public life. A commissioner in the community. |

The liberal policy, the development of the means of transport and of trade relations, placed Galician Jews in a significant role of economic life, and not only in trade and banking, but also in industry. However only limited strata of the community managed to improve their economic standing. The majority, who earned their living as retail traders, pedlars, craftsmen or employees, struggled for their existence and had to leave the small towns to seek employment in towns or in the capital. Due to the poverty and the difficulty in finding employment, many chose to leave Galicia and migrate to other parts of Austria or overseas. During 1870–1880 the move was to Vienna, Bukovina, Romania and Hungary, but from 1881 onwards the migration flowed toward the United States. The numbers of the Jews migrating from Galicia were as follows:

In the period 1881–1890 36,600 Jews In the period 1891–1990 114,000 Jews In the period 1901–1910 88,000 Jews Total 239,000 Jews[1]

The composition of the migrants by occupation was made up of: 34% craftsmen; 16% labourers, commercial assistants and salaried employees; 0.4% free professionals.

The lives of Lwów's Jews were improving. The town of Lwów, which had been neglected by the authorities who had no interest in its advancements and development, grew and progressed nonetheless since 1867, after the introduction of the Constitution and the integration of Galicia's administrative autonomy. The autonomous regime brought back the town's Polish character. The autonomous authorities and the town's administration introduced sanitary improvements and sewerage; roads and routes were laid around the town which improved the means of transport and the health of the population; the educational network was adapted to the needs of the population and buildings suitable for elementary and secondary schools were constructed.

For several years, Lwów was the cultural centre of the Polish people.

Considerable economic and cultural changes affected also the Jewish population. In 1869, the number of Jews who resided at Lwów was 26,694, and in 1880, there were 31,000 Jews (28.2% of the population); in 1890, their numbers reached 36,130 (28.2%); in 1900, 44,258 (27.7%); and in 1910 there were 57,000 (27.8%).

During the period of emancipation a particular phenomenon of conversion, previously very rare, appeared in the lives of Lwów's Jews. The integration into local life and the assimilation, drove unstable elements to abandon Judaism.[2]

In the years 1868–1877, the number of Lwów Jews who converted to Christianity was 55 (20 men, 35 women); since then, the number of converts grew: in the years 1878–1887, 157 (66 men, 91 women); 1888–1897, 245 (109 men, 136 women); 1898–1907, 256 (124 men, 132 women).

During the entire period 1868–1907, 713 Jews converted (319 men, 394 women), 486 of them (203 men, 283 women) became Catholics; 126 (46 men, 80 women) turned Greek Catholics; 73 (52 men, 21 women) became Greek Orthodox; 3 (1 man, 2 women) became Evangelicals; 25 (15 men, 10 women) became of no faith.

[Pages 305-306]

During the same period, 56 Christians converted to Judaism, (32 men, 24 women), 33 of them had been Catholics (21 men, 12 women), 7 had been Greek–Catholics (5 men, 4 women), 5 had professed no religion (3 men, 2 women).[3]

The establishment of the Vienna–Lwów–Chernowitz railway line, together with the rest of the routes within Galicia encouraged the economic growth of the town and drew Jews from provincial towns to find their livelihoods there.

Most of the export trade from eastern Galicia westwards, was in Jewish hands: wheat, cattle, horses, agricultural products and timber, as well as the import, eastwards and towards inner Galicia, of colonial goods, clothes, footwear, industrial products and agricultural machinery. In 1860–1870, the industrialists Schmelkes, Klein, Grüner and Schimer established beer breweries, the products of which were famous throughout Austria.

The industries of provincial–towns, such as: petroleum and timber products, had their managerial and commercial executive centres also at Lwów. Jews supplied railway sleepers to Austria and Germany; masts and construction timber for boats at Stettin [Szczecin], Danzig [Gdańsk], Trieste, Hamburg and England. Jews established transport companies, freight transportation, brokerage, insurance and agencies.[4] Hundreds of Jewish families made their living in these industries.

The vast majority of the wholesale trade, the large warehouses of textiles, leather goods, food, beverages, agricultural appliances, was also in Jewish hands and employed many clerks, assistants, labourers and salaried employees. Among the better known Jewish wholesalers were Natansohn, Aszkenazy, Kokris, Wahl, Klarfeld, Beiser, Epstein, Kolischer, Sprecher, Glantz, Wixel, Stark and Halpern.

During 1866–1885, wealthy Jews also invested large amounts in the purchase of land and estates, giving rise to a class of Jewish estate owners that included the Jewish pioneers of Polonisation, who supported the Poles' policies in Galicia. The families Horowitz, Kolischer, Mieses, Löwenherz, Parnas, Lazarus, Baczes, Landesberger, Dubs, Wahl, Buber, Kellermann, Rozmaryn Frenkl, Tom, Niewelt, were among Galicia's first Jewish estates owners, and many of them had their offices at Lwów. These estate owners employed Jews also as clerks and in agricultural work.

In the town proper, the Jews bought plots and built residential blocks in new quarters. In the field of building–construction were involved Sommerstein, who bought the Zamarstynów estate which for long was known as “Sommersteinhof”, followed by Selzer, Jonas and Sprecher also constructing residential houses.

The flow of Jews from the provincial towns increased especially after the events of 1846, for fear of the peasants' revolt, and those who arrived were lessees, owners of spirits distilleries, middlemen estate owners engaged in trade, small scale industry and contract work or those who purchased houses and plots of land. Among these the known names were: Agis, Sokal, Klein, Beer, Parnas (who already in 1835 leased estates in Podolia),[5] Tenner, Landau, Kimmelman, Rochmis, Schönfeld, Blumenfeld, Pipes, Rohatin. They made a large donation to expand the town and its buildings and with their contacts they turned Lwów into a trade centre between East and West. They were especially successful in expanding the trade relations since Brody had lost its free–trade status, and many of its merchants, agents and wealthy citizens left and settled at Lwów where they continued to develop the economic contacts with Vienna, Germany and Russia.

Among the affluent Jews of Brody who moved to Lwów were: Löwenherz, Mieses, Inlender, Braunstein, Mendelsburg, Bernstein, Kornfeld, Trachtenberg, Margulies, Kellermann, Garfein, Haberman, Jekeles, Sobel, Byk and Reizes (who established a large bank at Vienna in 1879).

The launch of Lwów's stock exchange on 1st January 1867, did much to stabilise the town's trade. Of the eight inspectors appointed to oversee the stock exchange agents and commissioners, four were Jews: Jozef Kolischer (manager of Lwów's branch of the National Bank), Chaim Hochfeld, Majer Mieses and J. Walach.

The Jews were active in banking too, whether as independent bankers or as branch–managers of Vienna's banks. Known among the independent bankers' names were: Horowitz, Jonasz, Lazarus, Mieses, Stroh, Kyc and Sztaf.

The economic standing of Lwów's Jews was indeed much better than in any other town of Galicia, where only one percent of the families had an annual income of 20,000 Florin; 4% had an income of 10,000–20,000 Florin; 10% had an annual income of 200–500 Gulden; 25% earned less than 200 Gulden; about 60% of the Jews subsisted on an annuity.[5A]

The most marked change occurred within the academic professions. Once full emancipation had been granted, education of the Jewish youth entered a new era, in which they attended the general schools.

Till 1848 Jewish children required a special licence from the authorities in order to attend secondary school [Gymnasium]. In 1848,

[Pages 307-308]

that requirement was rescinded, leading to an increased number of Jewish secondary school pupils, and later of university students. Prior to 1848, the number of Jewish students who studied Law at the university of Lwów, was low: in 1825, 2 Jews; in 1826, 4; in 1827, 9; in 1828, 6; in 1829, 4; in 1830, 6. During the years 1831–1848 their numbers did not increase much.

The increased numbers of Jewish students at Lwów University during 1851–1870 can be ascertained from the numbers below; one needs to note that Jews from Lwów also studied at the universities of Kraków and Vienna, and as there was no faculty of Medicine at Lwów, many had to study medicine elsewhere.

The number of students at Lwów University was:

Law Faculty

1851 – 17 Jews, 285 non–Jews 1860 – 42 Jews, 284 non–Jews 1870 – 38 Jews, 484 non–Jews

Philosophy Faculty

1851 – 25 Jews, 64 non–Jews 1860 – 6 Jews, 59 non–Jews 1870 – 13 Jews, 160 non–Jews

Technical Institute

1851 – 46 Jews, 127 non–Jews 1860 – 22 Jews, 207 non–Jews 1870 – 35 Jews, 230 non–Jews

A different impression is conveyed by the figures of Jewish students at Lwów University and Technical Institute during 1881/2–1901/2

The number of students at Lwów University, by Faculty:[6] Techincal Institute:

Years Law Medicine Philosophy Non–Jews Jews % Non–Jews Jews % Non–Jews Jews % Total of whom Jews % Total of whom Jews % 1881/2–1885/6 532 88 16.5 – – – 127 15 11.8 762 103 10.4 199 33 16.6 1886/7–1890/1 650 139 21.4 – – – 145 28 19.3 762 103 10.4 199 33 16.6 1891/2–1895/6 814 208 25.6 33[a] 10 30.3 164 33 20.1 762 103 10.4 199 33 16.6 1896/7–1900/1 1162 276 23.8 134 44 32.8 206 41 19.9 1863 361 20 573 64 11.2 1901/2–1905/6 1307 415 31.8 89 42 47.2 761 104 13.7 2718 561 22.3 1045 234 22.4

Until 1894/5, Jews from eastern Galicia studied medicine at the universities of Kraków and Vienna. In 1905/6, the number of those studying philosophy increased markedly due to the profusion of secondary schools and because it was a requirement for teaching.

For 20 years (1870–1890), the numbers of university graduates increased and each year the numbers of lawyers and physicians grew markedly.

Lawyers:

In 1890, out of the 91 lawyers at Lwów, 33 were Jews (36.3%); in 1900, out of 168, 67 were Jews (39.9%); in 1910, out of 241, 137 were Jews (56.9%).

Physicians:

In 1890, out of 124, 30 were Jews (24.2%); in 1900, out of 242, 53 were Jews (21.9%); in 1910, out of 342, 103 were Jews (30.1%).

The academic intelligentsia played a very prominent role in Lwów's Jewish public life.

Despite the changes afforded by the constitution, however, the Orthodox began to demand rights in the community. They were prepared to take over the community's key positions. To begin with, they demanded that the civil registration books (of Births, Marriage and Deaths), be handed over to Rabbi Saul Natansohn. They objected that the Rabbi be required to obtain a marriage licence from the preacher, “the coordinating rabbi.” The dispute was most acute within the community regulations' committee, during debates on the relations between the rabbi, the judge of the [rabbinical] court, and the preacher of the Temple [synagogue]. The lecturer Dr. Kolischer proposed the following wording: “The religious issues of Lwów's community are under the authority of the Rabbi and his two [religious] judges, one of whom is the Temple preacher.” Dr. Filip Mansch proposed, on the other hand, that: “If the preacher were a Torah scholar, then he would be the judge of the [rabbinical] court.” Members of the Orthodox community headed by Aron Ettinger, strongly objected to that, so in order to avoid any conflict with the Orthodox, the chairman of the committee Dr. Hönigsmann proposed accepting Dr. Kolischer's version. In respect of the civil registration books, it was decided that their administration be handed over to a specially qualified clerk rather than leaving them with the preacher. Dr. Ignacy Nossig, the community secretary, was appointed for the task.

That did not bring to an end the conflict between the Orthodox and the Enlightened, however. In 1868, a new community committee was elected that consisted mostly of enlightened members: Majer Rachmiel Mieses, Dr. Landesberger, Dr. Hönigsmann, Maurycy Kolischer, Dr. Juliusz Kolischer, Dr. A. Fränkel; (2A) and from the Orthodox: Ozjasz [Isaiah] Menkes.

Dr. Hönigsmann managed the welfare

[Pages 309-310]

and Charity[b] institutions; Maurycy Kolischer, education and school affairs. (3) The community affairs continued in the spirit of mutual tolerance, and the Enlightened attempted to expand the range of public institutions. The physicians who practised in the hospitals were Dr. Maurycy Rapaport, Dr. Silberstein and Dr. Witz. Great stress was laid on the issue of schools: already in September 1867, the community committee had unanimously decided to introduce the instruction of the Polish language at Jewish schools. Concurrently, an association was formed to spread the Polish language among the Jewish population. The association was headed by Dr. Hönigsmann, (4) Markus Dubs, M. Kolischer, Jozua Mieses, Rabbi Löwenstein, Dr. Juliusz Kolischer, Dr. Filip Zucker and Dr. J. Fränkel. The desire to publish a newspaper for the Jews was also realized with the establishment of Szomer Izrael [Shomer Israel; “The Guardian of Israel”] association.

Two contradictory political strands emerged among the Jewish intelligentsia: Centralists, supporters of the Austrian Liberal party, who were disappointed by the Poles and their anti–Jewish ploys at the Galician Sejm. Abraham Mendel Mohr's [Yiddish] newspaper Tsaitung (1869, Issue 9), openly objected to the Poles and their hypocritical friendship with the Jews, which they had solely cultivated in order to benefit from it. “The Poles wish to see the Jew as the ‘Moszko’ and ‘Icko’ of yesteryears. Times have moved on, however, and were the Poles to continue with their anti–Jewish policies, the Jews will know how to respond, and the Poles can forget any assistance from the Jews during the Sejm elections.”

A contrary view was held by a small minority of Jews who supported the Poles and their aspirations against the centralist government.

The leaders of the centralist's group, Rubin Bierer, Dr. Filip Mansch and Dr. Josef Kohn initiated, in 1867, the idea of establishing the association Szomer Izrael. Its main purpose was to protect the Jews' human rights, to spur the [Jewish] masses to political public action in the community and the town, and to establish a Jewish representation at the Sejm and at the Austrian Parliament; to disseminate the ideas of the Enlightenment and of civilization; reconciliation and cooperation with the non–Jewish population; to develop Galicia in order to ensure that the emancipation be realized in practice. The Orthodox and the Chassidim considered Szomer Izrael an organ for the dissemination of Enlightenment. Members of Szomer Izrael were joined by the best of the Maskilim, the academic intelligentsia and the community, in attacking the Orthodox and the Chassidim for objecting to the expansion of schools.

The Association maintained a club with a library containing Jewish–studies books and newspapers in Hebrew and other languages. Lawyers, physicians, merchants, Maskilim and also observant Jews gathered at the club to read newspapers, listen to lectures and discussions on the issues of Judaism. Dr. Filip Mansch was the first chairman of the association. The association's German weekly Der Israelit edited by Jakub Klein, was at first printed in Hebrew script, but later also in German. Among the association's activists was the young lawyer Dr. Emil Byk (1845–1908), born at Janów he injected the centralist, anti–Polish bend into Szomer Izrael.

Szomer Izrael first entered the political arena in the October 1869 Sejm elections. At the voters' meeting on 20th October 1869 held at the Temple of the Enlightened, the leaders of the association (Dr. Mansch, Dr. Henryk Gottlieb, the preacher Löwenstein and Dr. Szymon Schaff) recommended the candidacy of Florian Ziemiałkowski, Karol Wild and Abraham Mieses (the son of Majer Rachmiel Mieses). Ziemiałkowski was elected, but Abraham Mieses, the candidate of Szomer Izrael failed.

In the 1870 elections, Dr. Herman Frenkel,[7] the Szomer Izrael candidate was elected at Lwów with 2344 votes out of 3550. The elections were very turbulent. The Polish “Democratic Society” opposed the Jews and distributed anti–Jewish flyers to the crowds. Conflicts even broke out on the street, with windowpanes of Jewish homes being shattered. In Kraków Square events reached bloody blows and the military had to intervene.

In 1870, Dr. Bernard Goldman who had participated in the 1863 Polish uprising, settled at Lwów and gathered around him a group from among the Jewish intelligentsia who wished to be assimilated among the Poles, and started to fight against Szomer Izrael.

However, due to the Poles' stance against the Constitution and their demand for federalism, which the Jews considered a danger to their standing, the relations between the Jews and the Poles became adverse. The experience with the Galician Sejm convinced the Jews that it was best to rely on the Vienna centralist government rather than on the Poles. The slanderous speech of the Sejm delegates Krzeczunowicz and Zyblikiewicz (in 1870 he declared that the Vienna parliament was “Jewified” “Źydzali”), and the fact that the Sejm did not chose a single Jewish delegate as representative to the Vienna parliament, indicated to the Jews that most of the

[Pages 311-312]

Polish statesmen were anti–Jewish, and what the Jews of Galicia might expect were Austria to become a federal kingdom.

The Poles fiercely criticised Szomer Izrael for its opposition to the Sejm's decision (1871) to Polonise the Germanic schools of Galicia,[10] and for its demand that the Kaiser not confirm that decision. Szomer Izrael demanded that parallel classes in German be formed at Lwów's secondary school.

The policies that Szomer Izrael followed, resulted from the Jew–hate that had spread within the circles of the nobility, the clergy and the Polish bureaucracy, whose propaganda was conducted under the slogan “Down with the Jews” (Precz z zydami). Immediately after the Constitution was declared, most of the Polish statesmen opposed equal rights. Consequently, the Jewish representatives were worried that if Galicia were to be granted autonomy, the Polish majority would annul the equal rights which the February 1867 Constitution had granted them. Thus, the representatives of the Jewish community, in particular the leaders of Szomer Izrael, sympathised with the centralist position which best suited Jewish life, and was similarly followed by Lwów's Jewish press.

In 1873 a new law was published which implemented the direct voting for the election of delegates to the Vienna parliament, rather than their election by the Sejms.

This change gave the Jews the opportunity to lead an autonomous policy.

On 28th May 1873, spurred by Szomer Izrael, the Jewish representatives from the towns of Galicia gathered and decided to stand in the elections as independent. At the gathering the “Central electoral committee of Galicia's Jews” was appointed, with Dr. Juliusz Kolischer its chairman, and Dr. Emil Byk its secretary. The committee announced no Jewish political programme, but declared its loyalty to the Constitution.[11] Dr. Szymon Samelsohn, chairman of the Kraków community who, while being member of the Sejm had voted with the Poles to boycott the Vienna Parliament, opposed the committee's stance. He advised the electoral committee even in writing, that the Jewish issues called for identification with Galicia's interests and that they were bound up with the destiny of the Polish nation for one hundred years. As a result, he refused to join the electoral committee. Dr. Byk retorted mockingly in an article in the weekly, Der Israelit, where he said that Samelsohn “goes around dressed in Kontusz and Karabela” (Polish national attire) with a curved Tatar sword on his belt.

In their desire to attract the Jewish vote, the Poles entered into negotiations with the Jewish electoral committee. The committee demanded assurance that six Jewish delegates be elected (at Lwów, Brody, Kolomyia, Stanisławów, Przemyśl and Drohobycz) and that in regions with a large Jewish minority, only Liberal candidates who opposed federalism would stand. The Polish electoral committee rejected the demands whereupon the Jewish electoral committee and the Ruthenian committee signed a technical elections agreement, but the Ruthenians who relied on the Jewish vote in the provinces, were obtained a disappointing result in the towns. Following Dr. Byk's proposal, at Lwów proper, the committee decided to recommend the Polish candidate Zbyszewski, rather than the federalist Czerkawski.

The elected Jews were: Dr. Hönigsmann (Kolomyia), Dr. Joachim Landau (Brody) and Hermann Mieses (Drohobycz), while the candidates, Rabbi Löwenstein (Przemyśl), Dr. H. Gottlieb (Stanisławów), Dr. Józef Kohn (Tarnopol) and Dr. Max Landesberger (Rzeszów [Reichshof]) failed to get elected. The elected representatives were also joined by Natan Kallier, who was selected by the Brody chamber of commerce, whereas Albert Mendelsburg, who was elected by the Kraków chamber of commerce, joined the “Koło Polskie [Polish Circle].” The four delegates from eastern Galicia together with the eight Jewish delegates from the rest of Austria's Lands (Vienna, Moravia, Bohemia and Bukovina) joined the Constitutional Party (Verfassungspartei) in parliament.

In January 1874, elections were held for the town council. Szomer Izrael together with the rest of the Jewish delegates formed an electoral committee and decided to form an independent Jewish list, because the Liberal citizens' committee had removed from its list of candidates, Rabbi Löwenstein and Dr. Józef Kohn, who during the parliamentary elections (1873) had recommended the Kingdom's Constitution over Federalism. A small number of members from Szomer Izrael (Rubin Bierer, Öhlenberg and Julius Hochfeld) proposed to abstain at the elections. Their proposal was however rejected and it was decided they stand for elections as an independent list.

The Poles, in particular Jan Dobrzański's newspaper, Gazeta Narodowa, conducted propaganda against the Jews depicting them as aspiring to Germanise Galicia. The newspaper called on the Poles to boycott the Jews economically. In 1874 their incitement had reached such levels that Szomer Izrael sent a memorandum to Dr. Glaser the Minister of Justice, with the request to order the government prosecutor at Lwów to act appropriately.[11A]

The new committee of Szomer Izrael elected on 29th September 1874, included Dr. Mansch as chairman, Dr. Byk, his deputy, Hilel Lechner as treasurer and Dr. Salomon Landesberg, as secretary.

Apart from the German language Der Israelit, there was also the Yiddish newspaper

[Pages 313-314]

Jüdische Presse, edited by Natan Samuely and Jakob Cwi [Tzvi] Sperling.

The community committee led by Dr. Juliusz Kolischer, expanded its charity and welfare work which included 53 societies and institutions at the cost of 75,000 Gulden, in 1873/4. Much attention was devoted to the system of religious education. In 1874 there were 69 Cheders at Lwów, where 955 children studied in gruesome sanitary conditions.

On the initiative of Rabbi Löwenstein, the community committee lobbied to introduce improvements to the Cheders, and to spent 7,731 Florins on Talmud Torah schools. His efforts were in vain however, as the Orthodox objected to the community's involvement in the internal affairs of the Cheders and the Talmud Torah schools. In 1874, the first soup kitchen was founded, and Rabbi Löwenstein was elected as its chairman and Dr. J. Fried as his deputy. The community's annual expenses rose to 57,960 Florins.

Dr. Kolischer worked in particular with regard to the two Jewish schools where 1,298 children studied, so that they be expanded to accommodate more children. Some 500 children attended the general schools. The spending budget for the Jewish schools was 36,000 Florins.

The “Marek Bernstein Foundation” used the interest it had accrued on children's craft training. Rabbi Löwenstein headed the fund's board of trustees. The community also supported the synagogues, the number of which had risen to 20.

The main activity of Dr. Kolischer and Dr. Mansch from 1871 onwards, involved compiling the community regulations. By the end of 1874, the regulations were submitted for the government's approval, which was granted by the Governorship on 13th October 1875 (No. 4464).

The Orthodox, who opposed the regulations, summoned the Jewish community at the Talmudic schools and the houses of worship and got their supporters to sign a written appeal, which was submitted to the Ministry of Religion at Vienna.

The appeal delayed the declaration of the new elections in 1876, and the authorities ordered to hold the elections according to the existing regulations of Joseph II. All the Orthodox candidates were elected. The elections were annulled, however, because the Minister of Religion also approved the regulations on 9th March 1877 with some minor changes. After the community had accepted the changes, the new regulations were approved on 11th July 1877 and the community called new elections, which were won by the Enlightened and Szomer Izrael. Those elected to the community committee were: Maks Epstein, Salomon Buber, Dr. Henryk Gottlieb, Dr. Filip Mansch, Majer Rachmiel Mieses and Dr. Juliusz Kolischer; from among the Orthodox were elected: Jozue Schmelkes, Ozjasz Horowitz. Dr. Majer Rachmiel Mieses was elected chair of the community committee. (11A)

The issue of electing a rabbi came up at that moment in time.

With the demise of Rabbi Saul Natansohn on 4th March 1875, the community committee advertised the rabbi's position. Two candidates presented themselves: Rabbi Isaak Aron Ettinger, member of the community committee, and his relative, Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein. The Jews of Lwów were split into two camps. The Orthodox demanded the appointment of Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein, grandson of the great scholar Rabbi Jakub Meszulam Ornstein who, together with Rabbi Naftali Herz Bernstein (1813–1873),[11B] had waged war against Rabbi Abraham Kohn. Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein who had been rabbi at Brest–Litowsk [Brześć Litewski] from 1865 to 1873, but was forced to leave because he was a foreign national, and was elected to become rabbi at Rzeszów [Resche]. In March 1875, the Orthodox dignitaries assembled at the synagogue outside the town and decided to demand the appointment of Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein. The community opposed his appointment because of the poisoning of Rabbi Kohn.[11C] The second candidate, Rabbi Isaak Aron Ettinger was particularly supported by the Chassidim who hated Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein for being a “misnaged” [objector to the Chassidic movement].

Neither the community committee nor the delegates from Szomer Izrael objected to Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein, apart from Hilel Lechner, a disciple of Reb. Nachman Krochmal, who openly opposed him.[12]

In the 9th and 10th May elections, Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein was elected Lwów's Rabbi by a substantial majority, and he came to town on 22nd June 1875. He took up his community post with a solemn celebration attended by the community dignitaries.

Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein, was a Torah scholar who had a broad education and was familiar with the German language and literature; he was tolerant and knew how to attract the Maskilim and the progressives. But he was hated by the Chassidim, with the Belz Chassidim led by the righteous Reb. Jozue Rokach, treating him with distrust.

The Jewish intelligentsia's views of Polonisation altered, which affected the policies of Szomer Izrael whom the Jewish public followed.

In 1870, Dr. Bernard Goldman, an active participant in the Polish uprising of 1863, settled at Lwów. In 1867 he arrived at Vienna and as a Congress Poland national he requested a licence to reside at Lwów to try and attain a lecturer position at the university.[12A] However, Governor Gułochowski

[Pages 315-316]

objected to his request, and Dr. Goldman remained at Vienna and became secretary to Rogowski, the Polish delegate to Parliament. Only in 1870 was he granted a licence to move to Lwów where he married the daughter of Rabbi Löwenstein.

Once at Lwów, he expressed his objection to Szomer Izrael, that considered him an instrument of Germanisation and an enemy of the Poles. In 1876, with the support of the Poles, he was elected a delegate to the Galician Sejm, and surrounded himself with those who favoured Polish assimilation. In 1878 he founded the Association “Dorsze Szulom [“Dorshe Shalom”; Peace Seekers]”, (Zgoda, in Polish), with the aim of improving the “social and political relation” with the Poles which had become unbearable due to the activities of Szomer Izrael. The Association which attracted members of the Jewish–Polish intelligentsia, was headed by Dr. Goldman, Maurycy Lazarus, Dr. Filip Zucker and Dr. I. Blumenfeld, a member of the town council. The Association published the Polish weekly Zgoda, with a bimonthly Yiddish supplement, but the supplement edition stopped after a few months.

Out of objection to Szomer Izrael, the Association even joined the extremists Orthodox in their battle against them. The Association was unable to attract a large number of friends and supporters however, because “the Jews of Galicia were unwilling to subject themselves to the mercy of the Poles,”[13] and six months later the Association dissolved and disappeared.[13A]

In contrast, the Association Szomer Izrael grew and its influence expanded. In 1868 it numbered 100 members, whereas by 1878 there were 650. In 1878, Dr. Emil Byk was elected its chairman. He started by preparing a conference of the delegates from the communities to debate the communities' work programme and how to unite them into an authorised and stable national organisation that would represent the entire Galician Jewry. To begin with, Dr. Byk attempted to attract Lwów's community committee to his programme. At first, the community leader Majer Rachmiel Mieses did not favour the proposal, but he eventually relented and the conference was scheduled for 18th June 1878 with the following agenda: 1. Regulations for the intercommunity organisation; 2. The establishment of a rabbinical seminary; 3. The question of the Jewish schools' fund from the period of Joseph II; 4. Sample regulations for the communities. The conference assembled at the Skarbek Hall and was opened by Dr. Emil Byk. Representing Lwów's community were: the chairman Mieses, Dr. Gottlieb, Dr. Mansch, the preacher Löwenstein and the secretary Dr. Ignacy Nossig. Szomer Izrael was represented by: Dr. Byk, Dr. Reizes, Mojzesz Buber, Rubin Bierer, Emanuel Frankel, Hilel Lechner, Becalel Menkes, Öhlenberg, Jakub Stroh, Dr. Maksymilian Sokal and S. Zimels. Representatives from 25 communities attended the conference. The topics on the agenda were discussed by the general assembly and by committees over four days.

Dr. Emil Byk spoke of the need to establish an intercommunity organisation, Brit–HaKehilot [“The Communities' Alliance”], to represent Galician Jewry and its institutions. Until the establishment of Brit–HaKehilot the conference would act in its stead.

In his address, Dr. Filip Mansch offered an overview of the Jewish schools' fund and demanded that the authorities be actively approached to hand over the fund's monies, to the future–elected delegation of Galicia's Jews. The deliberations mostly focused on the founding of a rabbinical seminary. In the committee, Dr. Nossig and Lechner expressed their views against modelling the proposed rabbinical seminary on those in Germany, Italy or France, as it would provoke fierce objection from the Orthodox. Consequently, it was better to establish a seminary for the teachers of religion, the lack of which was noticeable in Galicia's schools.

Following heavy arguments the committee accepted preacher Löwenstein's suggestion to establish a Jewish studies seminary which would satisfy the country's requirements, with special consideration laid on the training of teachers of religion. The plenum rejected the committee's proposal. The extremist Enlightened maintained that one should not yield to the Orthodox, and that a decision be adopted for the establishment of a rabbinical seminary. During the debates young Chassidim burst into the conference hall, shouting: “Gentiles; Epicureans; ‘Treifniacs’ (those consuming non–Kosher food); a priests' seminary.” The police were alerted and with difficulty they were removed from the hall. The intruders were led by Samuel Horowitz, the son of Ozjasz–Leib, the future leader of Lwów's assimilated Jews.

The committee decided to convene also a second “Communities Day” and to prepare the communities' regulations and a plan for the rabbinical seminary. A permanent committee was elected, which tasked Dr. Ringelheim (Tarnow) and Dr. Mansch (Lwów) to prepare the communities' regulations. Emanuel Frankel submitted to the committee a plan for establishing a rabbinical seminary. According to his proposal, there needed to be established: a) a four–classes' preparatory school for 9–14 year–olds, where the Bible, Talmud and secular studies be taught at a low–level secondary school; b) a six–years advanced school of Talmud, Jewish studies and secular studies at advanced–level secondary school. After the matriculation examinations the students would attend the three–years course of the Talmud faculty. Upon completing the course, they would be accredited as rabbis.

[Pages 317-318]

The communities' conference decision with regard to the rabbinical seminary, alerted the Orthodox's camp. On 17th July (17 Tamuz) 1878, a rabbis' gathering led by Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein assembled at Lwów and decided to use any means to delay the realisation of the rabbinical seminary. According to the rabbis' gathering, a demand had also to be made that Jews should avoid the services of Jewish lawyers and physicians, so as not to “fall into the hands of those amending the [Jewish] religion.” Rabbi Szymon Schreiber of Kraków was elected the convener of the rabbis' gathering, and with the aid of Isak Dajcz [Daitch] of Vienna, they hoped to succeed in lobbing circles of the Vienna government. Rabbi Szymon Schreiber, Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein and the Belz Rabbi produced a proclamation to all the communities, in which they declared that the decision of the communities' conference was more damaging and dangerous than all the Spanish persecutions and Inquisition.

The rabbinical seminary thus led to a “cultural battle [Kulturkampf]” in Galicia, which the Orthodox conducted with extremism and exceptional fury.

The Orthodox established an organisation by the name of [Kol] Machsike HaDas [Upholders of the Faith] and published a lithographic newspaper in Yiddish: “[Zeitung für] das wahre [Orthodoxische] Judentum [(Newspaper for) the true (Orthodox) Judaism]” in which they disseminated articles of incitement against Szomer Izrael. Later on they published a weekly Machsike HaDas in Hebrew. In February–March 1879, a three curiæ [tribunals] election to the communities committee was held without any party war, as the Enlightened and the Orthodox had reached an agreement, and Majer Rachmiel Mieses was elected its chairman; those elected from among Szomer Izrael members were: Lazarus, Dr. Szymon Schaff, Dr. Filip Mansch, Dr. H. Gottlieb, Dr. Emil Byk, Jakub Stroh, Salomon Buber, Dr. Filip Zucker; those elected from among the Orthodox were: Jakub Jüttes, Rabbi Isaak Aron Ettinger, Samuel Schönblum, Jakub Diże. The elected deputies were: S. Landau, Mejer Bach, the pharmacist Dr. Zygmunt Rucker – all Szomer Izrael candidates.

In the same year, 1879, elections were also held for the Vienna parliament. On that occasion, the Jews sided with Poland. Most leaders of Szomer Izrael led by Dr. Emil Byk “took the view that the Jews' interest was best served by joining the Poles.”

The Poles also preferred to add Jewish representatives to their list, to prevent the formation of a Jewish–Ruthenian agreement like the one of 1873, which had weakened the Poles' lists in Eastern Galicia.

The Poles' central electoral–committee of Eastern Galicia, offered four seats on the committee to the Jews, out of the Poles' 16.[14] After negotiation it was agreed on four Jewish representatives, as long as they joined the Polish faction in parliament (Koło Polskie).

Ever since 1879 the Jewish policy aligned itself with that of the Poles: support for the centralist government had passed, and its leaders were fully on the Polish side.

Government circles discussed the issue of the communities. The government was keen on bringing order to the communities by formulating approved regulations to which all the communities throughout Austria would have to adhere. The initiative came from the Galician Sejm in 1876, when it demanded to regulate the Jewish community in accordance with clause XV of the basic law.[16]

Regulating the communities in accordance with legal statutes, was a matter that also preoccupied the Jewish population.

In 1881 an enquiry was held into the issue of the rabbis and the communities, initiated by the Minister of Religion, Baron Conrad von Eybesfeld, and attended by rabbis, progressives and communities' representatives of the lands of Austria. The participants from Galicia were Natan Kallier and Rabbi Szymon Schreiber who had put forward the request to do away with the need for rabbis to present educational certificates, and to grant them the right to exclude from the community people who did not follow the faith. His demands were not answered, and so he decided to call Galicia's communities to act in the spirit of his proposals. On 15th February 1882 he held at Lwów a gathering of rabbis from Galicia and Bukovina, which was also attended by some representatives from small communities. Rabbi Szymon Schreiber, a follower of the Hungarian Orthodoxy, proposed community regulations, of which Clauses 2, 41, 58, 78 determined that the communities had the right to expel Jews who did not follow the Shulchan Aruch [abbreviated form of the Jewish ritual law]. Any community resolutions that contravened the Shulchan Aruch would be invalid. His actual intention was to give the rabbis absolute authority over the communities. The [his] entire set of regulations aimed at removing the progressives from the communities. He had in mind the example of Hungary where, after the “communities' congress” (14th December 1868–24th February 1869) the unified communities were split into three separate communities. Galicia's communities objected to the doings of Rabbi Szymon Schreiber, and sent telegrams of protest to Lwów's community, and many communities demanded that their rabbis quit the communities' gathering. Protest meetings against his proposals were also held in the towns. The rabbis' gathering, which was abandoned by many before it ended, accepted the proposed regulations.[17] Rabbi Szymon Schreiber, who was a parliamentary delegate, submitted the proposed regulations to the Minister of Religion. However, 51 of Galicia's foremost communities submitted to the government strong objections to the proposed regulations. In March 1883, Rabbi Szymon Schreiber died, and his proposal was also rescinded on his demise. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Religion

[Pages 319-320]

and Education could not remain indifferent to the many objections, and decided to reach a permanent arrangement regarding the communities. In 1880 Taaffe's government had already worked on the communities' regulations, but it took a long while for the right opportunity to submit it to the Council of Ministers for approval. On 19th January 1888, the Council of Ministers debated the proposed regulations brought by the Minister of Religious Affairs, Baron Gautsch [von Frankenthum]. On 21st March 1890, the communities' regulations for all of Austria's lands were published.[18]

In April 1882, after the Rabbis' gathering, new elections were held at Lwów for the community committee. Influenced by the previous gathering, only the progressives' list was elected, and no one from the Orthodox was elected.[19]

The Jewish intelligentsia espoused Polish assimilation. In 1880, Dr. Goldman and Dr. Filip Zucker established Agudas Achim [The Brotherhood Association] (Przymierze Braci) which led the assimilation movement till 1890, and published the Polish weekly Ojczyzna [“Homeland”] with a Hebrew supplement “A reminder of love for the homeland”, edited by Isaak Aron Bernfeld. Dr. Emil Byk, one of Szomer Izrael's leaders, also joined the group.

The Polish intelligentsia's stand was formed by the concepts of Aleksander Świętochowski, Elizia Orzeszkow and Henryk Rewakowicz, who viewed Poland's Jews

|

|

| Kol HaKore Davar BeIto [a flyer in Yiddish; warning call about the current plight] |

favourably, and warmly welcomed the establishment of a group of assimilationists at Lwów, hoping to see the assimilation of Jews into Polish society.

At Lwów and the provincial towns, the assimilated also launched cultural undertakings such as Polish language evening classes. They fought against the Lwów community which, according to them, followed the spirit of Szomer Izrael and the Austro-Germanic policy. However, the differences of opinion were smoothed over little by little through political integration with the Poles, and their aspiration to turn the community “into an institution imbibed in Polish spirit” was realized under the influence of its leaders, and with the assistance of the Polish authorities.

In the ‘80s, in contrast with the desire for the Jews' integration into Polish society, a prominent antiSemitic movement arose among the Polish people. During the 1880–1881 session of the Galician Sejm, the Polish delegate Teofil Merunowicz proposed to limit the Jews' equal rights. The committee which considered his proposal, included the amendment that the Jewish community's rights and authority be curtailed. The committee's proposal was unanimously accepted by the Sejm.

In the same year, the age–old conflict between the Polish and the Jewish merchants flared up again. The newspaper Gazeta Narodowa and its editor, Jan Dobrzański, known for his liberal and pro–Jewish publication in 1848 and 1863, called on the Poles to establish a Polish middle–class that the nation undeniably lacked. Although he did not call for the boycott of Jewish trade and its people, his call was interpreted as a call for war against the Jewish traders. A call to boycott Jewish trade and to displace them from all economic fields was openly declared by Galicia's Sejm delegate, Teofil Merunowicz, whose declarations turned him into a leader of Lwów's townspeople. His stance was also supported by Prince Adam Sapieha.

The Jews of Galicia and of Lwów in particular, underwent a serious crisis. And were it not for the assistance from organisations from foreign countries, Galicia's Jews would have been in a dire situation. Although in 1880–1890 there was talk of self–help, no attempt was undertaken due to the indifference of the few affluent strata within the Jewish population. The desire was also missing, to join forces to create congenial conditions to ameliorate the situation, as: professional education and strengthened trade, credit,[19A] expanding the crafts, establishing a cooperative network etc. Among Lwów's community, which was the centre of Jewish life and was suited to manage internal issues, there were only few individuals who sensed the situation and were able to conclude that it had to be changed.

[Pages 321-322]

In 1880–1882, tens of thousands of Jewish refugees from Russia passed though Lwów on their way to America. The community established an “aid committee for refugees.” Representatives arrived also from welfare organisations from England and France, Sir Montague, Dr. Asher, [Emmanuel Felix] Veneziani, Karl [Charles] Netter as well as the British Chovev Zion [Lover of Zion, i.e. supporter of Jewish immigration to Palestine] Laurence Oliphant who was received by the community leader, Salomon Buber, who “stood by him”.[c]

Despite the manifestation of anti–Semitism as a political movement, the leader and parliamentary delegate Dr. Emil Byk tried to convince Galician Jews that “anti–Semitism is a plant that sprouted only at Vienna, but not on Polish soil.” The community espoused Polonisation. The 1883–1888 elected community committee, nominated as its chairman Dr. Filip Zucker, who was in the vanguard of the Polish assimilation. The committee members, Samuel Horowitz deputy chairman, and Dr. Emil Byk, had also abandoned the old policy of Szomer Izrael, the others on the board were Dr. Henryk Gottlieb and Samuel Kellermann. Dr. Zucker and Dr. Byk were on amicable terms with Galicia's governors, Count Alfred Potocki and his successor [Filip] Zaleski, as well as with other Polish statesmen, and they shaped Galicia's Jewish policy according to their desires.

The education of the Charedi youth was a subject that preoccupied the Jewish leadership in a significant measure. In 1885, the Viennese [Israelitische] Allianz embarked in Galicia on an intensified action in the field. They rented a house at Lwów, and 25 Cheder Torah–teachers declared publicly that they were willing to introduce secular studies at their Cheders. Nechemiasz Landes, headmaster of the school named after [Tadeusz] Czacki,[20] prepared the curriculum. A central Cheder was also established for youths under the age of 18.

In 1884, the preacher Löwenstein established the school “Ohel Moshe [Moses's Tent]” (named after Moses Montefiore) where children from poor families were given Jewish and secular education. 78 pupils enrolled straight away. The undertaking was supported by Szymon Landau. The preacher Löwenstein, a man with nationalist aspirations, wanted an education for the youth that was embedded in Jewish values and that prevented from being absorbed into the Polish assimilation that pervaded the general schools. However, the school and the Cheders supported by the Allianz, faced opposition from the Orthodox. In a meeting headed by Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsh Ornstein, he attempted to explain to the Orthodox that in view of the government's comprehensive educational requirement, soon to be imposed on the population, it was advisable to secure a suitably structured religious school. At the meeting, the leader of the Chassidim, Aron Piepes, declared that “religion and culture are at odds, like fire and water”, and the meeting strongly objected to any change in the “Cheder” system and demanded to keep the educational system as it had been and as it was, despite Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein's explanation. Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein left the meeting in anger and continued to support efforts on that matter.

|

|

| Dr. Ozjasz Thon |

Under the community's initiative, in March 1885 an amended Cheder, initiated by the community, was opened at Lwów, in which 381 pupils enrolled. Six Torah teachers taught religious studies and eight teachers taught secular studies, in accordance with the elementary–schools' curriculum. The preachers Löwenstein and Nechemiasz Landes were involved in the matter. On preacher Löwenstein's initiative, holiday camps for Jewish school children were also established. Dr. Goldman and Jakub Stroh headed the board responsible for maintaining the holiday camps on behalf of the community.

Education and elementary schooling had preoccupied most members of the intelligentsia, who believed that with knowledge of the Polish language and with cultural integration, the Jews would gain the sympathy of the Poles, and that the pervading and growing anti–Jewish undercurrent would abate. On 16th March 1890, Agudas Achim whose primary aim was to exhort Polish assimilation, convened a referendum headed by Count Jan Tarnowski; among the Poles who attended were the renowned statesman Count Stanisław Badeni, Dr. Zdzisław Marchwicki, Tadeusz Romanowicz, Dr. Józef Wereszczyński, Dr. Zagórski, Dr. Ludmił German, Jan Franke; and from among the Jews, Dr. Emil Byk, Dr. Filip Fructmann, Dr. Natan Löwenstein (the son of the preacher Löwenstein). The issue debated was “what steps need to be taken in order to improve the situation of Galicia's Jews; how can one improve their education and what steps are required to ameliorate their economic condition.”

After comprehensive deliberations it was concluded that it was desirable to increase

[Pages 323-324]

the number of Jewish pupils at state schools, under the compulsory education rule, by offering special terms to keep the [Jewish] holidays and the Sabbaths, and the teaching of religion to be undertaken by experienced teachers with a general education. Consequently, they proposed to establish at Lwów a seminary for teachers of religion as well as a rabbinical seminary. Lwów's community prepared a curriculum for a four–years seminary. The curriculum included the study of the Hebrew language and grammar, the Bible with commentaries, Talmud, Shulchan Aruch, dogmatics and its origins, ethics and Jewish philosophy, history of the Jewish people, history of Jewish literature as well as the methodology of religious studies.

Seminary students were also obliged to follow secular subjects at a state's seminary. The community attempted also to obtain funds from Allianz for the project, but to no avail.

In 1878 the community had already sent the Sejm a memorandum, based on the decision of the first community assembly, but the matter was transferred to the Sejm's education committee only in 1884, after a fresh request from the community and from the general pedagogical association had been submitted.

The committee decided that by acknowledging the need to establish a specific course for Jewish teachers of religion, the Sejm had declared its willingness to allocate a set amount, with the proviso that Lwów's community on its own or together with other communities, would raise the majority of the expenses; tuition would be in Polish and the Sejm would have a say and appropriate supervision over the institution.

|

|

| Adolf Stand |

The Sejm accepted the resolution on the 28th November 1890.

In its attempt to secure the allocated sum, Lwów's community was prepared to shut the girls' school[21] and transfer its 6,000–Florin annual budget to the seminary. The community committee headed by Dr. Szymon Schaff, made this decision in its meeting on 5th December 1891.

The authorities delegated the settling of the matter to the town council, but the town council objected to the closure of the girls' school.[22] to avoid overburdening the municipality financially, as a result of the girls' transfer to a municipal school.

The rabbinical seminary and the Torah–study school never came to fruition. In 1902, after protracted negotiations with the national committee (wydział krajowy) and with the Vienna Ministry of Religion and Education, as well as on the opinion of the universities of Lwów and Kraków, Lwów's community decided to establish a private institution to train teachers of religion from amongst the Jewish pupils who were attending the state teachers' seminary.

Inevitably, the Orthodox objected to all the proposals and plans, and stood fast while continuing to attack the progressives, in their newspaper Machsike HaDas, which after the demise of Rabbi Szymon Schreiber became wholly reliant on the Rabbi of Belz's coterie.

The group of Lwów's Orthodox headed by Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein, who had changed his mind regarding the Jewish policy (during Rabbi Abraham Kohn's tenure he had been fanatically devout) but by and by reconciled himself to reality and to the requirements of his time. The transformation was also a result of Samuel Horowitz's leadership of the community, which he held from 1888 till 1903.

In 1888, when an organ was installed in the Temple, the Orthodox started another conflict with the community committee. Their representative, Jakub Ber Sokal, delivered a strong protestation to the community committee, but with Dr. Byk following Rabbi Löwenstein's view, the dispute was brought to an end once it was agreed that the organ would not be played on the Sabbath.

With the demise of several leaders, Lwów's community underwent changes. Young blood appeared on the horizon and took control.

After the demise of Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsch Ornstein in 1888, Rabbi Izaak–Aron the son of Rabbi Mordche Zew Segal Ettinga (Ettinger), was elected to succeed him. Rabbi Izaak–Aron Ettinga was neither an extremist nor a fanatic, and contributed much to ground the community which had been unsettled by the Orthodox and the influence of the Rabbi of Belz's coterie.

On 15th March 1889, the preacher Isachar Ber Löwenstein died. Among the candidates to succeed him were Dr. Samuel Cwi [Tzvi] Margulies (born at Brzeżany [Berezhany]) and Rabbi Dr. Isaiah Gelbhaus (born at Buczacz [Buchach]). The Polish authorities disqualified them both, as neither knew any Polish. Dr. Bernard Goldman proposed the candidacy of Nachum Sokołow, who had come to Lwów and held a sermon in Polish at the Temple of the Enlightened in the presence of the synagogue managers and a large crowd, which left a great impression on the listeners.

[Pages 325-326]

Sokołow returned to Warsaw, however, and his candidacy was annulled. It appeared that the authorities refused to accept a candidate proposed by Dr. Goldman.

In 1891, Rabbi Löwenstein's post was filled by Dr. Jecheskiel Caro, the son of Rabbi Józef Chaim Caro, the rabbi from Włocławek [Leslau] who officiated at Pilsen [Plzeň], Bohemia.

The community was led by Samuel Horowitz and Dr. Emil Byk, while the education committee's affairs were managed by Dr. Samuel Schaff. All three of them tried to expand the community's charitable and welfare activities. A women's committee was established, led by Dr. Adela Inlender, to provide clothes, footwear and food for pupils of impecunious families. On 17th June 1888, following the community's petition, the government issued a regulation that the salaries of the teachers of religion be paid for by the government or the state. On 1st December 1889, a law was issued to determine the arrangement and grading of the teachers of religion at elementary schools. Dr. Peszt succeeded Dr. Ignacy Nossig as community secretary.

The communities' legal status underwent a marked change. On 1st March 1891, Baron Gautsch, the parliamentary and upper–house (Herrenhaus) Minister of Religion, submitted the regulation “regarding the religious community of Jewish faith” which was passed without objections, apart from some unrelated anti–Semitic speeches delivered in Parliament as pure propaganda.

The law only set the boundary that determined the scope and area of the community and its authority, the role of the holy servants (The rabbi, his deputy, Dayanim [Jewish ritual judges], caretakers), institutions and relations with the authorities. Clause 28 stated that the communities had to prepare a plan specifying the boundaries and area of the community, the composition of the administration, its election and the period of its tenure, its role and powers; regulations regarding the rabbi, his election, his authority, his rights and obligations; the rights and obligations of the community members, election regulations, the community institutions' maintenance and management; the regulations of synagogues and private Minyanim; the budget and taxes. The regulations and any alterations to them had to be submitted to the authorities for approval. A form for the communities of Galicia containing 93 sections was appended to the statute.[23]

During 1891–1892, Lwów's community worked on preparing sample regulations (Musterstatut) in accordance with the policy–form set by the government for all of Galicia's communities. The communities, apart from those in a few towns, had no existing regulations. The regulations were prepared by a committee made up of Lwów's community representatives, rabbis and governmental agents, and were unanimously accepted.[24]

In 1891 (16th January; 7th Shvat 5651), Rabbi Izaak–Aron Ettinga died and the community set about electing his successor. Among the candidates were Rabbi Izak Schmelkes of Przemyśl, Rabbi Arie–Leib Braude, Rabbi Weiss of Czernowitz [Czerniowce], Rabbi Rohatin of Złochów [Zolochiv] and Rabbi Izak Chajes of Brody. The rabbi's election by 80 adjudicators took place on 7th February1892; 34 voted for Rabbi Izak Schmelkes, 25 for Rabbi Arie–Leib Braude and all the other candidates received 21 votes. The election of Izak Schmelkes was secured.[24A]

The community had also to elect the Jewish school's headmaster. On 15th July 1893, Dr. Bernard Sternberg (1823–1893) died; he had been headmaster for 45 years and contributed much to its educational progress and the increased number of its pupils and teachers. Dr. B. Sternberg was also active in the public life, and especially in the management of “The Temple of the Enlightened.” Under his management, the school played an important role in the cultural life of the Jews of Lwów. He was followed as headmaster by the teacher Mendel, and in1899 Dr. Samuel Gutmann (1864–1935) was appointed on an annual salary of 2,400 Crowns. On 14th February 1909, Dr. S. Gutmann left his post as headmaster after being appointed rabbi and preacher, and the school was managed by the teacher Samuel Szlagowski, and after his demise Herman Spät was appointed headmaster (till 1934).

During 1890–1895 the Zionist Organisation evolved at Lwów. The youth and the academic intelligentsia were instrumental in the movement Chibat–Zion and showed interest in Judaism, after the period of assimilation. The Zionist movement and the social, cultural and political impact on Jewish life, associated with the awakening of the Zionist concept will be discussed in the chapter “The History of the Zionist Movement[”][d]

Attempts were made at Lwów and Galicia to provide economic assistance to craftsmen, retail salesmen and pedlars. In 1898, JCA [Jewish Colonisation Association; IKA] established “loan and saving funds” as well as a cooperative association for credit. Youths' training courses in crafts, and evening classes for general education were formed with the assistance of different institutions.

Intensive work was also undertaken to establish a hospital, founded by Maurycy Lazarus[24B] who donated the funds to erect a new hospital with 80 beds. In 1902, the hospital was expanded and its cost rose to reach 600,000 Crowns. His wife donated another 60,000 Crowns for internal furnishing. Lazarus handed the hospital, which was constructed

[Pages 327-328]

and fitted to suit modern medical practices, to the authority of the Jewish community.

In 1902, a new orphanage was opened as well; it was established by Dr. Szymon Schaff and his wife in memory of their daughter Otylia, who had died young. The community also constructed a new building – a home for incurable patients.

Following the publication of the 21st March 1890 community regulations, organising the rabbinate turned into an urgent issue. Since 1870, the community debated the integration of the preacher post at the “Temple of the Enlightened”, together with the rabbinate. Due to the deep rift with the Orthodox over the community regulations and the rabbinical seminary, it became impossible to settle the matter. In 1891 when Dr. Jecheskiel Caro was appointed, he was assured that once his tenure had become permanent in 1895, his rabbinical appointment would also be settled. Nevertheless, all attempts to negotiate with the Orthodox resulted in their objection to the preacher being appointed community rabbi.

|

|

| Dr. Dawid Schreiber |

With the confirmation of new community regulations, the community committee wanted to implement the appointment even against the position of the Orthodox, because the regulations included a special clause on the maintenance of two rabbis at Lwów. The opportunity presented itself after the Governorship had approved the community regulations at Lwów, on 23rd December 1897.

In 1898, community elections were held in accordance with the regulations. Twenty–seven community elders were elected, out of which seven would form the management board, and twenty would form the council. To the board were elected: Dr. Emil Byk, Chairman; Dr. Szymon Schaff, deputy chairman; Salomon Buber, Dr. Józef Czeszer, Dr. Henryk Gottlieb, Jan Landau, and the engineer Emil de Mieses; to the council: Jakub Beiser, Dr. Salomon Bund, Dr. Jakub Diamand, Jakub Diże, Mendel Feigenbaum, Dr. Wilhelm Holzer, Eliasz Hescheles, Samuel de Horowitz, Dr. Jakub Horowitz, Moritz Jonas, Dr. Maurycy Lazarus, Dr. Jakub Mahl, Dawid Maschler, Filip Natansohn, Samuel Nebenzahl, Leib Rosenfeld, Wilhelm Sakler, Maurycy Silberstein, Jakub Stroh, Mojzesz Dawid Wein.

One of first tasks of the new community committee was to settle the rabbinate issue.

Following clause 30 of the regulations submitted for approval, it was determined that the composition of Lwów's rabbinate should at least include two community rabbis, with equal status as the rabbis throughout the entire Lwów area: one Orthodox rabbi, and one progressive rabbi who was tasked, apart from his role as preacher and rabbi, also to supervise the religious studies in all the state schools.

Besides the two rabbis, the community had to maintain a rabbi for the synagogue and a rabbinical court.

Based on the above clause, it was possible to appoint Dr. Caro as community rabbi. Following clause 34 of the regulations, 30 arbitrators and nine deputies were elected from among members of the “Temple of the Enlightened”, who, together with the community council (with 39 votes in favour against 15), appointed Dr. Caro as community Rabbi on 25th May 1898.

Although his appointment followed the regulations, the Orthodox submitted a written appeal to the municipality, signed by their leaders: Febus Ebner, Nachum Burstin, Mendel Margoszes, Lejzor Gutwirt, Abraham Juda Alter, Hersz Brazer (known as Herszele Zorn) and Jakub Okin. The municipality did not respond to the appeal, but passed it to the Governorship.

On 11th June 1898, the community president Dr. Emil Byk swore in Dr. Caro as community rabbi together with Rabbi Izak Schmelkes and Aleksander Halpern. On 20th February 1899, the Governorship rejected the appeal by the Orthodox and confirmed the appointment.

The question of the religious education in primary and secondary school was also on the agenda. The 1899 regulations confirmed the primary and secondary schools' posts of teachers of religion. Due to the lack of teachers of religion with pedagogical qualification, the lessons were taught by general teachers who were seminary graduates.

In secondary schools the situation was much the same. Since 1883, Dr. Józef Kobak[25] taught the secondary schools' upper classes, while the lower classes of the fourth secondary school were taught by Jakób Klein, who had been the editor of Der Israelit since 1868 till his appointment as teacher of religion, in 1883.

As inspector of religious studies, the community tasked Dr. Caro to prepare the curriculum. Once Dr. Caro had submitted his curriculum, it was passed into law by the national educational council, on 30th August 1895.

[Pages 329-330]

In order to appoint the appropriate teachers for all schools, and secondary schools [gymnasiums] in particular, the community committee negotiated with Galicia–born graduates of Vienna's rabbinical seminary.

That led to the appointment of the following, as religious teachers: Dr. Mojzesz Schorr, Dr. Bernard Hausner, Dr. Spinner, Dr. Majer Balaban, Hirsz Bad, Zygmunt Taubes–Sens, Dr. Majer Tauber, Dr. Lewi Freund and Dr. Samuel Gutmann.

At the same time, the community debated again the erection of a seminary for teachers of religion which had already been approved of by the Sejm. In 1894, the Sejm representative Dr. Bernard Goldman, brought the matter for discussion, and in 1898 the authorities accepted the opinion of the universities of Kraków and Lwów. On 19th October 1902, after a lengthy negotiation, the “Institute for teachers of religion” was opened, headed by Dr. Caro, who led the institute till 1913. The active lecturers were Dr. Gutmann and Dr. Hausner. Under Dr. Caro's initiative an “Association of Jewish teachers of religion” was also founded throughout Galicia. Dr. Caro did not sympathise with the teachers of religion who gravitated towards Zionism, but supported the leaders of assimilation, which led him to public conflict with the Zionists. When the assimilationists demanded to withdraw the teaching of the Hebrew language, he did not object, neither did he object when, in 1904, the Land's education committee under the influence of the assimilated, forbade the teaching of Hebrew during the lessons of religion. All the teachers of religion were willing to obey the order, except for Dr. Majer Balaban who declared it impossible for him to teach religion by following the Polish translation of the Bible – Wujek translation; due to his objection, the Land's education committee annulled the prohibition.

In 1905, following Dr. Majer Balaban's proposal, the convention of teachers of religion decided that religiously speaking it was necessary to teach also Hebrew, and Dr. Caro yielded to the teaching staff's wish.

In 1899, under the initiative of Dr. Majer Munk (of Hamburg, son–in–law of Samuel Rokach (a very wealthy man and among the leaders of the Orthodox) and with support from the community, the Chinuch LaNoar [Education for the Youth] school was established to teach the Hebrew language; in the afternoons, secondary–school pupils studied there Hebrew language, grammar. Bible, Mishnah and Shulchan Aruch [abbreviated form of the Jewish ritual law]. The studies lasted four years. The appointed headmaster was the pedagogue and Hebrew–Yiddish writer, Izak Ewen (1861–1925). Ewen was educated within a Chassidic home, but he “enlightened himself” and became a teacher. He published articles and stories from the lives of the Chassidim in Machsike HaDas and later in HaMagid (Kraków); at Borysław he established Galicia's first Hebrew school. In 1895 he moved to Lwów where he founded a modern school for teaching Hebrew, and in 1899 he accepted the role of headmaster of Chinuch LaNoar school.

|

|

| Bernard Goldman |

In 1902, Ewen left the school and Dr. Gutmann replaced him as headmaster.

In March 1899, the Jews of Lwów faced a difficult municipal council election struggle. The Poles' election slogan was “Delete” the Jews from all candidate lists, in order “to maintain the Christian character of the town of Lwów.”

Of the 100 members on the municipal council, only 18 were Jews, even though they were entitled to 25% of the mandates

After a tough conflict, 18 Jewish members were again voted in: Rabbi Izak Schmelkes, Rabbi Dr. Caro, Dr. Emil Byk, Dr. Natan Löwenstein, Piepes–Poratyński, Dr. Bernard Goldman, the pharmacist Blumenfeld, the pharmacist Jonas Beiser, Dr. Mahl, Dr. Pisek, Dr. W. Holzer, Dr. A. Reiss, the merchant Fried, the banker Jonas, the industrialist N. Mayer, the pharmacist Dr. Rucker, the industrialist Sprecher, Dr. Edward Lilien.

During the ten years before the First World War, public life underwent big changes. The Zionist Movement kindled an interest in Judaism among Lwów's Jewish community and especially among the intelligentsia and the educated youth. Shoots of the Jewish Workers' Movement which spread from Lwów to the rest of Galicia, were also visible. Associations for workers, trading assistants and craftsmen were formed, and some joined the Polish Socialist Party (P.P.S. [Polska Partia Socjalistyczna]). Zionist workers' associations were also formed during the 1903 Kraków conference, such as Poale Zion [Workers of Zion].

Some of the Jewish workers who had joined the “P.P.S.”, left and set up a Jewish association titled “Z.P.S.” (Żydowska Partia Socjalistyczna), this was followed by the P.P.S. forming a “Jewish Section” which dissolved before the First World War, with some of its members

[Pages 331-332]

joining the Z.P.S. which formed associations that encouraged their national and social status recognition.

Although the assimilated were in charge of the community (In 1903, Dr. Emil Byk followed Samuel Horowitz as president of the community, and with support from the authorities they were elected to represent the Jews in the municipality, the Sejm and the Vienna parliament), their influence diminished within the Jewish population. Dr. Emil Byk's total control over the community aroused dissatisfaction also within the circles of the assimilated who were inclined towards democracy, and who took their revenge on him at the Sejm elections of 1898, by voting for Jakub Bojko, the leader of the Polish Peasants' Party, despite his inclination towards anti–Semitism.

While the committees of the welfare institutions JCA, Baron Hirsch Fund as well as the B'nai B'rith society, the Lwów branch of which was founded in 1899, were still controlled by the assimilated who influenced public life, nevertheless their hold diminished here too, as the influence of the Zionist Movement increased.

The community's activities included: 1) religious issues; 2) education; 3) welfare institutions; 4) monies and legacies. The community controlled an annual budget of 300,000 Crowns, in addition to the budgets of schools, hospitals, orphanages and soup–kitchens. The 1901 budget, for example, was made up as follows: 297,000 Crowns taxes, income and miscellaneous (of which 50,000 Crowns taxes; 247,000 ritual slaughter and legacies). The expenditure came to 308,000 [Crowns], made up of: the rabbinate – 17,980 Crowns; schools' maintenance[e] –10,334 Crowns ; kosher food for soldiers and the sick – 4,000 Crowns; professional training for orphans – 7000 Crowns; 9,620 Crowns to feed schoolchildren; 30,000 Crowns on support of cultural and welfare institutions; 1,000 Crowns for the Vienna rabbinical seminary; 400 Crowns for the Chinuch LaNoar school; 8,400 Crowns on pensions; 26,000 Crowns on administration. In 1904 the schools' budget rose to 82,190 Crowns, compared with the 73,256 in 1898; the hospitals' budget was 136,555 Crowns in 1904, compared with the 109,502 in 1898; the orphanage 35,543 Crowns in 1904, compared with 32,150 in 1898; the welfare fund 9,345 Crowns [in 1904] compared with 12,022 in 1898.

Apart from these budgets, the community had at its disposal the income from some 60 legacies of contributors and donors, the incomes which were largely allocated to the needs of the hospitals, the orphanage, welfare institutions and the granting of scholarships. The legacies came to 755,643 Crowns. In particular the 100,000 Crowns legacy donated by Samuel de Horowitz for the establishment of a loan fund for traders and tradesmen, needs to be mentioned. Its profits provided for 224 loans in the sum of 22,175 Crowns, in 1899 alone. The loan fund operated until the first world war.[26A]

In 1905 a plan to build a new “Temple” on a large plot in the town–centre facing the Sejm building, was discussed. However, objections from the state–governor to the construction of a synagogue near the Sejm, and the death of Dr. Byk (1906), put an end to the entire plan. The existing “Temple” was actually enlarged, two galleries were added and its interior was renovated.

The general economic crisis and the boycott by the Polish anti–Semitic parties (“the National Democrats” and their magazine Słowo Polskie) together with the Ukrainians, led to the dwindling economic life of Galicia's Jews. The decline also affected indirectly the lives of Lwów's Jews, despite the fact that the economic conditions there were much better than in other communities. The Jews held key positions in wholesale trade. Known are the textile wholesalers Abraham–Ber Ludmirer, Balsambaum, Spiegel on “Breitegasse [Wide alley]”; the import–fruits wholesaler Friedrich Schleicher; iron merchants Sprecher, Saul Birnbaum and Salomon Rappaport; wholesale furriers Gerszon Wolf and Singer; hat manufacturer Bernard Waldmann. The fruit trade was concentrated in the hands of Nachmann Luft, who travelled to Trieste to bring southern fruits including etrogs.

The “Agricultural Union” (koła rolnicze) at Lwów, tried to prise the trade in grains, cattle and agricultural produce, out of the hands of the Jews. Similar attempts were also made by the Ukrainian Cooperation, notwithstanding, the Jews held on firmly until 1914. In the hops trade Zygmunt Flecker was known, as was Leib Wahl in the timber trade.

The Jews advanced and did well, also in crafts. Among the well–known craftsmen, the artistic locksmith Führer; the tinsmith Müller; the joiner Fand; the mechanic Weich; the stone mason Judam; the fresco painter Falk; the house painter Staude; the engraver Szapira, need to be mentioned, who excelled not only in the quality but also in the artistry of their work, and who were also known outside the town of Lwów.[27] Best known was the carver (chiseller), the jeweller Boruch Dornhelm (1853–1928), who excelled in artistic work known abroad too. He learnt engraving

[Pages 333-334]

and carving from his father Salomon, who was known by his work throughout Lwów. His sons Boruch, Szymon and Jakob worked for him at his workshop, and produced precious works of art.[27A]

Boruch Dornhelm was a trained craftsman and his work was also in demand at Vienna, Berlin, [Saint] Petersburg, Budapest and London. He integrated Jewish motifs in his work, and his copper and silver openwork “the Exodus from Egypt”, “Moses”, “the Binding of Isaac”, “David and Goliath” and “Samson”, are well known. In 1907 he moved to Vienna, where he lived for the rest of his life.

|

|

| Dr. Jan Piepes-Poratinski |

Already in 1892, the Vienna Allianz and Österreichisch– Israelitische Union [Austrian–Jewish Association] had started on rehabilitation activities and founded the Hilfsverein für die notleidende jüdische Bevölkerung in Galizien [Association for the needy Jewish population of Galicia]. To that end, by developing home–industry the association created sources of income that occupied 4,000 people, including many from Lwów, whose annual income reached 300,000 Crowns.

Allianz also extended subsidies to schools and to students' welfare societies, and the German–Jewish association Esra supported kindergarten and orphanages. The community and its Lwów institutions were conducted in an orderly fashion. Vienna and foreign countries considered the Jewish Lwów “a town attached to Galicia by geography alone.” The Zionists insisted on introducing democratic order in the community, and under pressure of their demands the community leaders began to look for constructive assistance.[29]

And then, amidst this process, the First World War broke out.

The period of the First World War, 1914–1918, constituted one of the bleakest chapters in the history of Lwów's Jews.

Immediately with the declaration of the war, Lwów was flooded by streams of penniless refugees from the Austro–Russian border towns of Galicia, forced to leave their homes under the Russian occupation. It became necessary to care for the refugees, feed them, and provide them with lodgings.

Under the leadership of Samuel de Horowitz, the community established a “Rescue Committee [Vaad Ha'Hazala]” of 100 members from all the parties and strata of the Jewish population. In a flyer published by the “Rescue Committee”, Jews were asked to donate clothes, food and money for the thousands of refugees arriving from the borders of Galicia.[30]

The “Rescue Committee” was very active and separated the aid to the refugees into different departments. Dr. Cecylia Klaften, Dr. Ada Reichenstein, Laura Olbert, Marja Mester, Marja Goldfarb, N. Mandel, Dr. Felicja Nossig, and C. Katz headed the “Women's Committee.”

Apart from help to the refugees, the “Rescue Committee” was also engaged in forming a legion of Jewish volunteers. The undertaking was headed by Dr. Efroim [Ephraim] Waschitz, a veteran of Galicia's Zionist Movement, chairman of the Gymnastics Association “Dror [Liberty]” since 1913. Under the influence of Dr. Sterner and Arie Kroch, Dr. Waschitz became interested in the Scouts Movement and published an enthusiastic article about the Movement in the Viennese weekly “[Die] Welt.” He was elected the Scoutmaster and held that function untill the outbreak of the World War.