|

|

|

[Page 91]

by M. S. Geshuri

Translated by Sara Mages

The horrific events that took place in the lives of the Jews during the uprising of the oppressor Khmelnytsky[1], may his name be blotted out, the events known as the “Decrees of 5408-5409” [1648-1649], did not skip the Jewish settlement in Lutsk. In the period of 5408 - 5409, also our brothers in the city of Lutsk were subjected to plunder and prey like in all other cities near and far, and many of them were killed in various and strange deaths for the sanctification of God's name, they, their wives and sons.

The story of the act is found in an objective lecture in the book, Yeven Mezulah[2], written by one of the Jewish refugee who was an eyewitness to the event. The acts and the events of the years 5408 - 5409 are a tragic chapter not only in Jewish history, but also in human history in general. We had to make a great effort to distract ourselves from them and erase their memory from our consciousness, so as not to despair of a good ending and hope for the future to come. And in the meantime, even before we could forget those years of murder, came upon us the Holocaust of the German Nazis, who were worst than their teachers, the Haidamakas[3], and turned the Decrees of 5408-5409 into a minor edition of what had happened in our generation. Nevertheless, we are not free to draw a line on what happened a little over three hundred years ago. The lecture of the event comes as an eternal historical indictment on the part of our people for what their oppressors had done to them, and continue to do to them without a break for two thousand years. The voice of the blood of our ancestors, and our forefathers, cries out from the earth, and this voice should continue to be heard from the end of the world to the end, until the tyrants' stone heart will melt.

The horrific years of 5408-5409 are a period of horrors in the history of the Jewish people. These years were a time of trouble for the Jews in Poland, Wolyn and Ukraine by Khmelnytsky's Haidamakas, and from there the decree spread across the communities of Lithuania. Tens and hundreds of thousands of Jews perished without a trial, and the cruelty of beasts of prey in human form, and complete peace of mind prevailed in the civilized world.

Many reasons led to the Haidamakas uprising led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky (Chamil HaRasha [the wicked] in our people's mouth), which shortly after was joined by the majority of the Ukrainian people. The uprising shocked the Polish State in the middle of the 17th century, and caused a holocaust on all the Jews within it, especially on those in its eastern districts. There was a sharp national contrast between the oppressed Ukrainian and the ruling Poles, economic and social contrast between the serf farmer and the land owner, religious contrast between the Parvoslav and the Catholic. The special power of the outbreak was based on the fact that the Ukrainian was usually a Parvoslav peasant, and the Pole was mainly a Catholic noble. The Jews in Ukraine were economically connected to the Polish nobility. The Jews in Ukraine were financially connected to the Polish aristocracy, but this connection did not make them an independent factor in this struggle. However, the blow hit the Jews with all its force more than any other group or class in the State of Poland. The uprising began in the Dnieper. But before Khmelnytsky managed to organize the Cossacks for a military campaign, the uprising of the serf peasants broke out in all areas across the San River to the east. The farmers organized themselves into gangs, attacked estates and cities, murdered and robbed. Maksym Kryvonis'[4] gangs of, who ran rampant mainly in the Wolyn territories and Podolia until the arrival of Khmelnytsky and his army, excelled in their cruelty.

The surge of events reached Wolyn at breakneck speed, after the Polish army was defeated on May 26, 1648 near Kherson and, with the withdrawal of the Polish army to the west and all of Eastern Wolyn was given to the gangs to which Khmelnytsky's Cossacks later joined. These bloody years also left their traces in Lutsk, although no direct certificates of the tragic events remained in Lutsk, and the reason is probably because the pinkasim [ledgers] from that period have been lost.

However, there is no doubt that Lutsk Jews felt the murderous hand of the oppressor's gangs. It is known to us that he, and his gangs, visited Lutsk and its neighboring cities. The holocaust against the Jews of the country came in a terrible and terrifying manner, and this is no place here to repeat the details of these terrible acts of cruelty, which the generation's writers recorded for eternal memory.

Two books contain articles on “those days.” The book, Yeven Mezulah [Abyss of Despair] by Rabbi Nathan Nata Hannover, was written in an impulsive and emotional style that depresses the soul to the core, and the reader seems to be inside the terrifying sights: the persecuted Jews who are in mortal danger when they are attacked by the enemies who seek their blood, women and children seeking escape and refuge, the cruel death is getting closer and closer and there is no savior, a terrible slaughter and blood spills like water, the last sigh from the heart of the slain and their lips whisper! “We will avenge the spilled blood of your servants” [Psalms 79:10].

The book, Tit Hayavan [“Place of Suffering”] (Venice 5410 - 1650), written by the Viennese Jew, R' Shmuel Faibisch son of R' Nathan Feidel, has historical value even though it is not properly established and it should not be placed on an equal step with the first book. In any case, the material in it is not fictitious or imaginative. This book is also based on various sources and hearsay. The cities mentioned are real because they existed then. In both books the tragedy of Lutsk is described in a few words, and the words make a strong impression on us, being a first-hand account of the riots.

It is not known why the historians and witnesses of “those days” were content to include the name of the city of Lutz among the names of all the Jewish settlements in Wolyn and neighboring countries, who suffered then, without giving more details about the actual extermination of the Jewish population. While they describe in detail what had happened in the cities of Kremenets, Ostroh, Dubno and other places, they skipped the details of the killings in Lutsk and contented themselves with stating the fact of the extermination of the Jews in Lutsk. And also this detail - that the hidden in it is greater than the visible. The fact itself comes in different versions, and the equal side of them, that they all come in the purpose of brevity. Here, Rabbi Natan Neta Hannover[5] summarizes in his book the murders in Wolyn in a short sentence: “Also in the country of Wolyn, in the Holy Community of Ludmir [Volodymyr Volynskyy], and in the Holy Community of Lubomla [Lyuboml], and in the Holy Community of Lutsk, and in the Holy Community of Kremenets and their branches, they made large

[Page 92]

killings of several thousand Jews,” without specifying how many Jews were killed in each location. While the Viennese, R' Shmuel Faibisch, describes the killings in a different way by dedicating a special sentence to each place. From him we find a few more details about Lutsk when he said: “And from there he went to the Holy Community of Lutsk where there were two hundred homeowners and great rich men, and there was a President of the Court and his name the honorable Master and Teacher Rabbi Man (Menachem), and almost all of them were killed.” It is not known whether some of Lutsk Jews managed to escape from the city and only those who remained were killed, or the Jews, who “were very rich,” protected their property and preferred to remain in the city, or stayed for another reason. However, there is no doubt that the description of the members of the generation requires an objective approach. The eyewitness of the destruction of the communities, and the mass murder of their people, do not need a special investigation into the details of the events and the number of the slaughtered. They want to give a vigorous expression of the size of the crisis as a whole in their articles. The sights of the horror, and the rumors of the horrors, join in their imagination to one catastrophic picture.

The Lutsk community that was destroyed was only one community out of hundreds. It is impossible to accurately determine the number of communities that were destroyed, and the number of murdered in those terrible years. HaGaon Rabbi Shabbatai HaKohen[6] (the Shakh), wrote that more than three hundreds of important communities were destroyed and more than one hundred thousand people were killed. According to another article, seven hundred and forty-four communities were destroyed and approximately six hundred and fifty thousand people were killed in severe torture. The destruction was total. The Jewish community in Polish states, which excelled in the study of the Torah and important political order, was severely hit by these events and did not recover quickly.

In the stories of the events of the Decrees of 5408-5409, we find many revelations of courage of those who were tortured in a horrific way, stood the test and did not abandon their religion and faith. The martyrs, who converted out of fear, were few in number and after the days of forced conversion returned to their Judaism with the king's consent. Women and virgins, as well as boys and girls, sanctified the name of God and stretched out their necks for the slaughter, or they preceded their cruel enemies and killed themselves so as not to be handed over to their pursuers. Besides the historical records that provided us with the memory of the events, there are also some legends about soft and gentle virgins who gave their lives for the sanctification of God's name and the protection of their honor. From lamentations, Selichot[7] and variations of El Male Rachamim[8] or Yizkor[9] we hear the sighs of the tortured and persecuted, and share ourselves in the grief of a painful nation.

According to the assumption of the historian Balinski-Lipinski, the Haidamakas gangs entered Lutsk on 22 August. The Karaites were also murdered by the gangs.

Slowly, slowly the Jews of Lutsk recovered from their disaster, rebuilt the ruins, and began to redevelop the trade. The authorities treated the Jews kindly and reduced their tax payment to a third of the general tax.

Translator's footnotes:

by Engineer Architect Mikhal Ptic

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

|

|

As one born in Lutsk and as an architect, I have dedicated myself to giving an account of the difficulties that stood before me when I took upon myself the task of describing the Great Synagogue in Lutsk. I had before me an object of great historical, architectural and cultural value that also occupied a respected place among the established Polish architectural monuments from the beginning of the XVII [17th] century. The history of the synagogue is closely interwoven with the life of the Jewish population in Lutsk since the beginning of the Jewish settlement in the city, so it is impossible to write about the settlement and avoid speaking about the synagogue.

The Great Synagogue in Lutsk was not only a center for the religious and communal life of the Jewish population, but also a symbol of its unity, an expression of its spiritual and cultural strivings, a registrar for its events, of its rise and decline, successes and defeats, a representative of its legal life, of the kehila [organized Jewish community] and so on.

We find descriptions of the synagogue in a series of textbooks on architectural history. Art historians carried out measurements of it, studying its distinctiveness, its proportions and forms and compared them with other famous synagogue architectural objects in Poland and abroad.

The Great Synagogue in Lutsk had a special significance in architectural history as one of the few objects that simultaneously filled the task of worship and of defense. It was at the same

[Page 93]

time both a synagogue and a fortress castle. In order to understand the significance of this fact, we must at least in short acquaint ourselves with the history of the era in which arose the necessity of building a new, special kind of synagogue.

The Lutsk synagogue was built in the era of robust construction in a series of European countries, and particularly in Poland. This era lasted more or less from 1580 to 1648 and it was recorded as the golden era in the history of Jewish culture by Jewish historians.

After the difficult years of persecutions and wandering during the second half of the 16th century, the situation for Jews partly improved. Jewish communal life developed and the relatively favorable economic conditions contributed to the development of Jewish culture. Humanistic knowledge, philosophical studies, Hebrew literature, medical and natural science spread among the Jews. Because of the growth of the city in the XVI [16th] century, the existing wooden buildings in the Jewish quarter were exchanged for brick.

In this era emerged the significance of the synagogue as a center for the religious and communal life of the Jewish population. In truth, the Jewish houses of prayer were further limited in their development by church rules that prevented the building of synagogues in the proximity of prayer houses of other faiths so that “the non-believers” [the Jews] would not disturb the [Christian] prayers of the divine service with the noise of their [Hebrew] prayers. However, to the degree that local conditions permitted, it significantly facilitated the construction of the synagogue on a higher spot, sometimes near a flowing river and so on, in agreement with the Shulkhan Arukh [Code of Jewish Law] and with Jewish law. In a number of cities, the synagogue was near the church or near the city hall, even a few dominating with their silhouette.

The wars that were carried on in the middle of the XVII [17th] century by the Polish magnateria [magnates – Polish aristocracy] and the Polish szlachta [nobility] in the eastern provinces and the fear of constant assaults by the Tartars and Cossacks forced the local regime to build fortifications and use every building opportunity to strengthen the cities, particularly those that were found on the eastern edges of the Polish Rzeczpospolita [republic]. A series of synagogues that were built at that time, according to the order of the king in Lutsk, Pinsk, Tikoczyn and elsewhere, were given a fortress character. A duty to provide the fortress synagogues with cannons and provide defenders in case of war was placed on the Jewish population.

That is the genesis of the Great Synagogue in Lutsk that was built in the years 1626-28, on the basis of the special privilege from King Zygmunt III [Sigismund III]. In accordance with the privilege (which in 1896 was located by M. Berson in the Royal Metrika [documents] Archive and published by him the same year in Baricht fun der Komisie tsu Forshn Geshikhte and Kunst [Report of the Commission to Research History and Art]), the Lutsk Jews received the right to build a brick synagogue on the same spot where the previous wooden synagogue was located – with the provision that soldiers and even cannons could be located and even cannons over the vaults.

The security situation of the city on the eastern border in a region that was constantly exposed to the unrest of war justified the above-mentioned demands from the king. The building of the tower on one of the points of the roof originated from the same security terms.

From the same sources we learn that shortly before the completion of the construction of the synagogue, the monks from the nearby Dominican monastery brought an accusation to the king that the synagogue had not been built in accordance with the decision of the Catholic Synod, that is: that it was too close to

|

|

In the sketches – the location of the tower. |

[Page 94]

the church and, therefore, they demanded a halt to building the synagogue.

However, the political situation of the city, which was exposed to war dangers, required a more sober approach to the matter. Therefore, as a result, the accusation of the Dominican order was rejected by the king and his new order permitted the Lutsk Jews to complete the construction of the building which also had a defensive character. However, there were certain doubts that the Lutsk synagogue was actually rebuilt completely from the foundation.

In the exhaustive work of my father, Eliezer Ptic, of blessed memory, about the history of the Jews in the city of Lutsk, a work that was based on serious historical sources, there is a fragment that was written by him about the Great Synagogue. There we read that Zygmunt III [Sigismund III], the Emperor of Grace, gifted to the Jews the old arsenal – that had been erected in the time of King Witold [Vytautas the Great] in 1380 – to be transformed into a synagogue. The arsenal constituted part of the defensive wall with which the old part of the city was surrounded. This part of the city was like an island, surrounded on all sides by the Styr River.

According to other reliable sources, an underground tunnel led from the synagogue along the eastern part of the city. The tunnel connected the Catholic church, Lubart's Castle, the Dominican monastery, the Pravoslavna [Eastern Orthodox] cathedral – at least to the building of the former Województwo [provincial governor]. In such a manner the synagogue, which was included in the defense system of the city on the island, could easily show a resistance to the enemy during a siege and simultaneously, with the help of the tunnel, maintain a connection with the part of the city that was found outside the island. In addition, the defensive character of the synagogue, the architecture of the tower that differed in a certain scale in its form from other parts of the synagogue and also the order of King Zygmunt III that the synagogue not lose its defensive function – advanced the hypothesis that the new synagogue was rebuilt from the old arsenal.

Here my conviction was confirmed by the form of the tower that based on its architecture, was similar to the architecture of the towers in Lubart's Castle. The weight of the form, the manner of using pilasters [load bearing elements] in the tower and its completeness testify to the kinship of its architecture to the architecture of Lubart's Castle, whose construction dates from the XV-XVI [15-16th] centuries. The fact, that in the course of 300 years of the synagogue's existence, the tower had not been plastered, although the building of the synagogue itself always was plastered, testifies to the tendency to emphasize the architectural distinctiveness and peculiarity of the tower – that does not touch the well-planned unity and the absolute harmony of this particular part of the building.

Naturally, I do not here undertake to make a sweeping interpretation about the correctness of this or other versions that are applicable to the construction of the synagogue; may a more competent art historian occupy himself with this. I will only show that the version that was advanced by my father, of blessed memory, in the middle of the 19th century in his work about the history of the Jews in Lutsk was not baseless.

I remember from my childhood that in the city they spoke about the existence of underground passageways from the synagogue to Lubart's Castle, that they visited the passageway with their school class with candles in their hands. They found underground corridors in shadows and, therefore, they were forced to stop going further.

The then ruling currents in the world of construction influenced the Roman [Renaissance] design of the Lutsk synagogue (beginning of the XVII [17th] century). The oldest known European synagogues in Worms (from 1180) and Regensburg (1227) consisted of two rows of rooms with six (in Worms) or eight (in Regensburg) vaulted parts. At the end of the 16th century, a new type of synagogue began to arise with nine vaults. The nine-vault solution consisted of bringing four columns into the middle of a square room, which supported the vaulting. In such a manner, they developed the possibility of enlarging the size of the room and, consequently, its reception ability. The introduction of the vaulting idea created a unified division of all four walls, of which all were divided into three parts. Simultaneously, the Torah ark and the bimah [elevated platform from which the Torah is read] received their defined and enclosed spots; the Torah ark – in the middle part of the eastern wall, and the bimah – in the middle area of the room. The four columns that surrounded the bimah underlined its special importance.

In this manner a monumental interior arose with a strongly accented center, and this enabled the use of a dome that would cause an increase in the height and this would be a reason for the conflict with the church and with the state institutions.

This was not an accidental solution. The attitude to the role of the synagogue in Jewish society really changed in that era. Placing an equal sign between the idea of religion and law, laying the main worth on studying and preaching and not on praying, fashioned the new type of

[Page 95]

|

|

nine-field synagogue [synagogue with a vaulting system], where the bimah filled the role of a dais and not the Torah ark. This had a deciding influence on the architectural solution of the room. The principle of placing the bimah on a platform, with a table for the Torah reader, so that whoever spoke could control the auditoria, determined the type of synagogue. This had its full expression in the Lutsk Great Synagogue.

The necessity of concentrating attention on two different points gave rise to the requirement for changing the arrangement of the seats. Therefore, from the beginning, the seats in the Lutsk synagogue often were moved – with the exception of those seats that stood at the eastern wall and near the bimah. In the 1920s, at the initiative of the then gabbaim [sextons] Avraham Gliklich, Yitzhak Kraun and others, permanent, beautifully carved wooden seats were placed [in the synagogue]. The interior architectural furnishings were then constructed and completed.

In the Lutsk Great Synagogue, steps with a small bridge led to the richly formed aron kodesh [Torah ark], which were enclosed by a wrought iron balustrade with a self-closing entrance. Near the steps were containers for the candles. On the right was the eight-branched menorah with a ninth branch for a shamas [the ninth candle used to light the others on Hanukah] as well as the cantor's pulpit. The floor of the bimah was elevated by several steps. The columns that buttressed the middle vault area – as if it underlined the special significance of the bimah – was an element that was architecturally and in terms of construction organically connected to the entire interior.

We see in the Lutsk synagogue how the above-mentioned tendencies underlining the centrality found their fullest expression. This shows the manner of covering the room with monasterial vaulting, the uniform splitting of the walls and how natural the architectural forms of the Lutsk synagogue were not an absolute self-creation. Perhaps, there are traces there of the secular architecture of the XVI [15th] century with its massively heavy, almost fortress-like assemblages, bound with the Gothic Renaissance tendency of that era of

[Page 96]

Polish architecture. This connection also had a connection to the construction technique and to the architectural forms.

However, not all wings of the Great Synagogue had the same historical worth. For example, the women's section and the entry do not originate from the same time as the main room. They were added later and they are not organically connected to the entirety of the synagogue. They even ruined the clean lines of the main room. However, the annexes were necessary in connection with the changes in the former views of the community and because of the necessity of enabling the women also to have access to the synagogue. From then, also comes the later cutting of openings to the main room and the screening of them with posts, grates and so on. Only the eastern wall remained without any additions and, therefore, only the eastern fašade preserves the original form of the Lutsk synagogue.

On the fašade we see the tendency toward a horizontal division of the walls, to adorn the attic with a rich architectural frieze that enclosed the room over the windows to bring out the outward appearance of the internal structure.

The manner of shaping the arcade of the main room is typical as the solution of the architecture of the XVI [16th] century. The attic was formed in a similar manner as in the secular construction of that era. The building of the walls is therefore characteristic. The walls instead buttressed the walls and increased the dimensions of the windows. The tower, which was erected in one of the corners, serves as a witness to the special defensive role of the synagogue.

The project authorship of the Lutsk synagogue, as of other synagogues of its type, has not yet been established. However, the relationship that can be noticed between various buildings of the same period (in Lwów [Lviv] and

|

|

[Page 97]

Ostrog [Ostroh]) show that the project consultants were the same.

The synagogue architecture of that era and particularly certain of its shadings, as for instance the Lutsk synagogue, comes across as the conception of a great architect that was worked on and realized by above-average artisans. There were several known Italian architects who built synagogues in the XVI [16th] century, but the authors of synagogues who come from the XVII [17th] century, mainly from its first half, were unknown.

Jewish synagogue builders appeared at the end of the 17th century and more in the XVIII [18th] century. However, this does not exclude the possibility that there were Jewish builders in earlier eras in Poland.

During the hundreds of years, the Lutsk Great Synagogue shared the fate of the city and of the Jewish population. All cataclysms and misfortunes that the state met had an effect on the synagogue building. In 1819, the synagogue was burned when a fire enveloped the majority of houses in the city. Thanks to the generosity of the Jewish population, the synagogue was quickly rebuilt. However, during the fires in the years 1845 and 1869, the innermost facility of the synagogue again suffered. They gathered a significant sum of money among the Jews and, in 1876, brought the interior of the synagogue back to its previous state. In 1866, the building was restored with the active participation of the gabbai [sexton], Shlomo Borukh Kirsztalko. Among the donors, the Lutsk woman, Miriam Soroka, particularly stood out.

The last tragic act of the Lutsk Jews did not exclude the synagogue. The German barbarians completely disregarded the cultural-historical worth of the Lutsk synagogue. After carrying out their murderous deeds on the unprotected Jewish population in Lutsk, they destroyed the old historic synagogue and transformed it into a warehouse for the items looted from the murdered Jews.

by Moshe Gliklich

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

There is a house of prayer in Lutsk that carries the name of Rabbi Wolf the Martyr. When we began to inquire about who Rabbi Wolf was who reached the level of martyr and that a house of prayer would be named after him, we were led to the old cemetery and the grave digger there showed us a stone headstone on which one could barely decipher this epitaph:

“A headstone for a holy man who died a cruel death, [suffered] cruel torment and died Apocrypha [in sanctification of God's name], the extraordinary, the observant Wolf, son of our master, our Rabbi, Reb Tovia, ascended to the heavens on Shabbos [Sabbath] and his judgement was given on 25 Tamuz 5522 [15 July 1792]. May his soul be bound up in the bond of eternal life.”

We have heard two different legends about Rabbi Wolf that differ in essence from each other. However, both versions end with the same theme of Apocrypha.

According to the first version of the legend, Rabbi Wolf was a pious scholar and, in addition, a great scholar of the Apocrypha. He also knew several languages. Lutsk priests often debated publicly with him about matters of

|

|

faith. However, he overcame them with great erudition and shrewdness and the priests always were left to derision and shame. His constant victories greatly irritated the priests; therefore, they searched for a suitable opportunity to take revenge on him.

[Page 98]

A new church had been built in Lutsk. Well-known priests and high-ranking members of the clergy came together for the celebration of the dedication of the church. The Lutsk priests complained to the guest priests about the unconquered Rabbi Wolf and sought their advice about how and in what manner they could vanquish him. All of them had the same advice, that Rabbi Wolf should again be called out to a public debate. However, this time, they, the [visiting] priests with their great wisdom, would put together a long note with difficult questions and hard problems. In addition, they, themselves, would take part in the debate, give Rabbi Wolf many difficult and interwoven questions and thus confuse and drive him crazy so he would not know how to answer.

They actually did this. They demanded that Rabbi Wolf come to a public debate and, as always, Rabbi Wolf consented to come this time.

A high, wooden platform was erected in the middle of the market. On a designated Sunday, in the afternoon, a great number of male and female peasants, whom their priests let know about the rare debate, came together from the surrounding cities and villages. At the designated time, the well-known guest priests, adorned in full splendor in their religious attire, sat down in a semi-circle. Rabbi Wolf also arrived, whom they took into their midst – and the debate began.

The acrimonious fight of words lasted for hours and finally Rabbi Wolf again this time vanquished everyone.

The distinguished priests were embarrassed in the presence of a large crowd.

They, the infuriated masters, with burning anger, along with the Lutsk priests began to seek a means not only to take revenge on Rabbi Wolf, but also to be rid of him so as not to suffer from further shame and indignities.

At that time there existed a bizarre law in Poland; that if a dead pig that was not theirs was found in someone's house, the person in whose house the pig had been found was obligated to give the pig's owner enough millet to cover the carcass of the pig when it was stood on its back feet. If the guilty one was not able to provide the millet, he would have to be placed in prison and the judges would carry out a punishment against him. The judges even had the right to sentence the person to death.

And the priests decided to turn this law against Rabbi Wolf, because the villains certainly knew very well that Rabbi Wolf was poor, would certainly be unable to honor the demands of the law to provide so much millet; they would then place him in prison and when he would be in their hands, the scoundrels would succeed in being completely rid of him.

And so it was: they killed a large pig and, at night, they threw it into Rabbi Wolf's house. When Rabbi Wolf woke from sleep, he found the carcass of the pig in his house. Before he looked around, the custodians of the law came and led him to prison.

They demanded the full measure of millet from him as ordered by the law and he could not provide it; the scoundrels, bribed by the priests, sentenced him to the gallows.

Before he was hanged, he was given a choice: if he renounced his faith, he would be granted his life. Rabbi Wolf died Kiddish HaShem and he exhaled his soul with Echad [the last word – “one“ – of the first line of the Shema – the central prayer of Judaism].

[So ends] the first version of the legend.

The second version of the legend says that the Jews of Lutsk were accused of a blood libel. A dead Christian child was hurled into the Great Synagogue and it was demanded of the Jews that they reveal the guilty one during the course of one month. If they did not do this, all of them would be murdered.

The Jews prayed in all of the houses of prayer, issued a decree asking for an extraordinary fast for the community, prostrated themselves over the graves of righteous men and martyrs, collected money and lobbied the regime – but futilely. The judges led by the priests maintained their stubborn order with great cruelty – reveal the “guilty one.“

When the period had passed – on a Sabbath eve, when the rabbi and his entire congregation of Jews were at the bathhouse – soldiers surrounded the bath, invaded inside and declared that if they did not reveal or bring the guilty one immediately right here on the spot, they would set fire to the bath on all four sides.

From out of the group came Rabbi Wolf, went over to the police and announced that he was the one whom they were seeking. He had murdered the Christian boy. There being no choice, the policemen arrested him and the Lutsk Jews were saved from death.

The endings of both versions say that the Lutsk Jews brought Rabbi Wolf to be buried at the old cemetery, crowned him with the name, holy man, and erected the above-mentioned headstone. And at the spot on which the gallows stood (or where the debate took place), they

[Page 99]

later built a house of prayer and named it in his memory.

The same grave digger who led us to the headstone of the martyr, Rabbi Wolf, also showed us very old headstones on one of which we could see the detail of the years 5422 (1662), 5428 (1668) and 5432 (1672). He also led us to the oyhel [structure over a grave] of two brother righteous men: Reb Yitzhak Ayzyk ben [son of] the righteous man, Reb Borukh, died in the year 5586 (1726) and Reb Yehuda-Heshl ben the righteous man, Reb Borukh, died in the year 5611 (1851).[1] Inside one of the rooms still stood the shtender [lectern] at which Reb Yitzhak Ayzyk had studied.

Translator's footnote:

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Reb Berish Wajnsztok was a Jew of medium height with an angular white beard, shorn into two points: on the right and on the left. He would often put the pince-nez [eyeglass] on his long, veiny and slightly fleshy nose to mask his one crossed eye. [He dressed] in the European style – he would carry his stomach a little in front and had the sure step of a person who understood how to respect his own worth.

Reb Berish was maskhil [follower of the Enlightenment], that is, a maskhil not in education but in his behavior: his only son studied to be a pharmacist; he went without a hat at home; he could have a drink with landowners and actually played cards with them.

It could be that his beliefs had not brought his progress as far as his income did.

He had a wine tavern. Given that there were no restaurants with “clubs” then, his tavern was a gathering place for all the landowners and officials because he was somewhat close to the powers that be.

The task of Reb Berish in the communal area was to be a delegate of the Jewish population to the inspector podatkovi [tax inspector]. We must say that he would carry on his mission with complete trust.

He would defend the poor and the rich like a lion and did this, completely unasked and without any benefit for himself. Where he could not persuade the inspector with words, he would persuade with a small glass of wine. All proceedings would take place in his wine tavern, redone and even completely annulled.

He would say about himself: “They will come to me again at my grave and show that here lies the righteous man, Reb Berish Wajnsztok. To the question: How will one know where my grave is located? There is an explanation: They will sense me, because there will be a strong aroma of whiskey and wine from me…”

Skorupka and Wesola Streets had not yet crystallized then. They were more or less like paths and back alleys through which the residents of Wielki (Boleslaw Chrobry), going through Szenkewicza, would shorten the road to Krasna… It goes without saying that Wolnoszcz did not exist at all: this was an unbuilt place that once belonged to Gitele Lichtenfeld, of blessed memory, and, later, to Kraunsztajn by inheritance.

In the same way, there also did not exist: Anski Street, Czackiego, Senatorska of which there still was no sign.

Beginning almost from the “suburban” synagogue, both sides of Szenkewicza Street were screened by a long orchard in which several houses were hidden among the trees.

I say several because actually on the right side (in the direction with one facing north) in addition to Reb Yehiel Ejnbinder's house and another cottage, stood a few wooden houses that belonged to Rivele “Poliak [Pole]” and, later, to her son, Reb Hirshl Rozencwajg.

There were five houses in total on the Lutsk side up to the old cemetery, which were the property of the lawyer Wardensi and the owner Olga Ivanovna Polanska. The so-called shtotisher shiptal [municipal hospital] of the time (gorodskaya bol'nitsa [urban hospital]) was located in the last house; as a result, the street was called Bolnitshnaya or Shpitalna.

[Page 100]

The so-call “old cemetery” was located at the borders of the present fences with the area that the kehila [organized Jewish community] buildings occupied – at which stood the oyhel [structure over a grave] of the same holy place.

During the [First] World War, in 1915, the occupiers took away the fences, threw down the headstones and made a transit road out of the cemetery.

I consider it my duty to remember favorably Reb Chaim Bakawiecki and Reb Yehiel Ejnbinder, who as gabbaim [sextons] for the khevra kadishe [burial society] in 1920, re-erected the fences, gathered the headstones and, above all, distributed the headstones and brought order to the grave of Reb Wolf the martyr, who has a historical significance for us.

Reb Yosef [no family name is given] descended from Galitzianer [Galician] ancestry. He was a great deal taller than his wife, slender, dressed in European clothes, always clean and neat. His slow and uncertain steps gave him the appearance of a fastidious man.

His handsome and genteel facial features were framed with thick white hair on his head and with a white, neat, broad beard on his face.

The dove-white greyness, the wrinkles on his face that spread like two fans near both eyes on the temples and the dear smile on his lips provided him with much sympathy and evoked trust.

Reb Yosef was a pious, God-fearing Jew in the best sense of this idea: his praying at the pulpit possessed a great deal of sweetness and the prayers were heartfelt.

The world of commerce was the sphere of his activity. He looked at commerce as at a tool, better said, as a laboratory that produced money while, in contrast, those Kraunsztajns saw in money the source of luck and prosperity, so they would devote all of their time to business. Here no sentiment existed, only numbers and sober calculations.

On the contrary, the management of the [Reb Yosef's] house was according to the Jewish religion and Jewish tradition: always his own minyon [10 men required for prayer]; he often gave a nice donation and, by the way, Reb Yosef, of blessed memory, always believed in giving charity in secret.

For his favorite [charities], that is, for the yeshiva [religious secondary school] and the Talmud Torah [primary religious school for poor children], he provided for them both when he was alive, giving hundreds of rubles a month for the expenses, and after his death he left according to his will, 20,000 rubles as a reserve fund, from which the institutions would be able to subsist.

Alas, this capital was devalued during the [First] World War and the yeshiva received no use of it.

At this point, it would be appropriate to recognize the great services done by Reb Yosef and Chaya-Rikele, of blessed memory, for this institution and the good will they showed with regard to this institution.

Finished with the yeshiva and Talmud Torah, we return to Szienkiewicz Street, with which we come to Park Miejski. The so-called Park Miejski first developed in autumn 1907. Until that time, this area and the surrounding streets, Kraszinskiego, Mickiewicza and Slowackiego, constituted one large, four-cornered, unpaved square that was littered in summer, muddy in winter and carried the glaring name, Paradni Platz [Parade Square].

No one knows why the square was named Paradni. I assume that even the author of the name had not given an account of it because no one remembers that parades or joy had taken place there.

It would have been better to have been named Tragowi [market place] or Handlowy [business] because on the market days the village wagons would stop there and fairs would take place there on the 16th of every month.

The sanitary condition of this square was criticized for everything and I do not exaggerate when I say that it was a nest for all kinds of microbes that would spread various infectious diseases over the entire city.

There were times during the year (mainly autumn and winter) when, because of the great filth, the square was impassable for someone walking and then movement took place on wooden footbridges that surrounded the square on all four sides. Luckily, the movement was insignificant because the area around the square was not thickly settled: two houses in total on the south side, of which one once belonged to Reb Yeshaya Bakser and later to Reb Shimeon Gliklich, of blessed memory. And the second one belonged to Ayzyk Kowal [blacksmith] (I do not remember his family name); on the west side was the plot of land of Reb Leib Bicowski with a few wooden houses deep in the courtyard that extended to Lubelska [Street]; between Lubelska and Slowacki Street was a wooden hut of the deliverer of clay, whose family name I think was Kopajko. The south side was completely unbuilt; here a large orchard extended, which belonged to the landowner Karwin-Piotrowksi, who we would call Panie Marshalku [Mr. Speaker] because once, before the powstanie [uprising] of 1863, he was chairman of the Polish nobles.

The barracks on Pilsudski Street were built approximately between the years 1888-1893.

The entrepreneurs were Reb Elihu Frumkin – a rich man from Warsaw who came from Lithuania – and his partner was also a Russian Jew, a certain Zigel (I have forgotten his first name).

[Page 101]

On the spot, in Lutsk, sat Zigel who led the entire construction work.

This Zigel was a tall, big-boned, healthy man, with a red shaved face and a small beard under his bottom lip. His appearance was like a true Russian, but he possessed the heart of a warm Jew who made sure more Jews were employed in the work so that more Jews would gain from his enterprise.

However, his great accomplishments consisted of this, that among the Jewish workers, he trained many qualified artisans. He did this in such a manner: to the qualified Christian workers that he had hired from away, he added local Jewish artisans who perfected their trade. So, for example, thanks to Zigel, [these were] Jewish masons, of whom no one in our region had any concept.

However, our workers not only learned the trade, they also earned a great deal of money.

The work was urgent. They worked day and night and Zigel paid generously because the business was a good one and because his precept: “Let Jews earn. The Jewish people need a livelihood” – was his beloved expression.

From their saved money, the artisans rented plots outside the city from Zakovski and built houses from which they later created a quarter named “Nova Zabudovanya.” The neighboring Leszcinski's brick factory, which also developed because of the barracks, greatly influenced its development and would at the time employ many workers.

During the period which my memories cover, the geographic shape, the border lines also changed: the Hlushets River, which began at the Styr [River] behind the Jewish cemetery, extended along Boleslawa Chrobrego and Jagielonska and flowed into the same Styr – at the point where the Manchna crosses Targova. The Hlushets had deep water in which one could sail and swim during the whole summer. Forty years ago, I, myself, swam behind the Bank Polska, near Bernardynska Street.

Likewise, Nova Zabudovanya was located on the shore of the so-called Staw Zaikovskich, which filled the Korita that extended almost to the village of Teremna, along Leszcinski's brick factory and Kolonia Uzszendnicza to Pilsudski Street. The River Sopolaievka that merged with the Styr began in this lake.

The Staw Zaikowskich [Zaikowiskich pond] was a full-fledged water reservoir. The fact that 40 years ago a water mill was found on the spot where the Sopolaievka cuts through the highway can serve as proof.

In such a manner, Lutsk consisted of two parts:

1. From the center of the city which made up an islet surrounded by water – on one side the Styr and on the second the Hlushets.

2. From the so-called suburb that with Wielke made up a half islet and which was washed with waves from the Styr on the west side, by the Hlushets on the south, Zaikovski's lake and the Sopolaievka on the south and only on the east side at the Dubna-Rovner city gate was united with dry land by a small strip.

The image of the city began to change at the moment when the construction movement began and, parallel with the development of this movement, the demand for plots of land [caused] the price to greatly rise.

Given that there were no plots because there was water all around and the city did not have room to spread, the people began to create plots when they began to fill in the Hlushets and the Zaikovski lake.

The filling was done primitively, chaotically, without any supervision on the part of the supervisory regime and resulted in two beautiful water reservoirs being turned into muddy swamps on which only here and there arose construction plots. The remainder resulted in nests for malarial microbes and other infectious diseases.

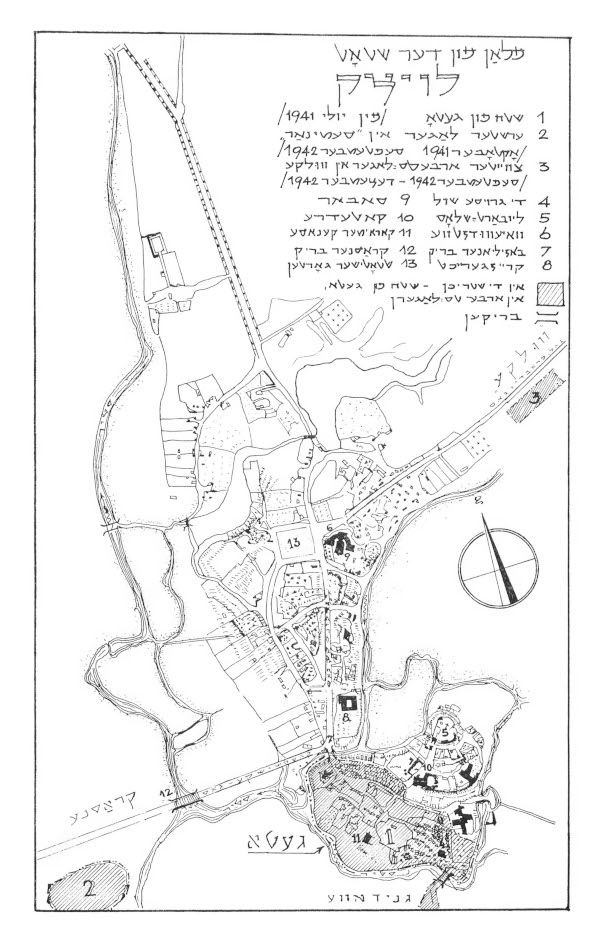

|

|

[Page 102]

|

Bridges [two vertical lines] |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lutsk, Ukraine

Lutsk, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Aug 2025 by JH