|

|

|

[Page 5]

Its History

by Yosef Ze'evi

Translated by M. David Isaak

In-between the thick forests and the swamps of Pinsk that existed since the beginning of time, nestles an out-of-the-way village called Luninyets. The village's inhabitants are Belarusian farmers. These uneducated peasants, immersed in ignorance and destitute in poverty were suddenly awakened from their dullness. Rumors circulated about iron railway tracks. The peasants couldn't believe what they heard and dismissed these rumors as fantasy. But as the days rolled on the fantasy became real: Engineers and officials arrived and started measuring, erecting huts, digging trenches and leveling depressions. Finally they decided that here, in this forlorn village, a central train station will be built. Not in Pinsk, the old town, and not in any other town, but, precisely, here.

They started draining the swamps in the areas of the future tracks. Hundreds of workers, among them specific professionals, were busy building houses and laying iron tracks on wooden crossties. Many of the local village inhabitants were engaged by the authorities for different tasks. When the train-wagons appeared for the first time, headed in front by the large steam engine, the farmers, seeing this great wonder, fell to their knees. The older ones crossed themselves. The year was circa 1880.

Early on, Jews in Luninyets worked in agriculture or in the sale of the farmers' produce. Among them were also craft workers, tinsmiths, blacksmiths and carpenters. The first settlers there were: Tzadok Lichtstein, Matisyahu Ditalowitski, Yisroel Treybuch, Zelig Lichtstein (the blacksmith), Shlomo Gershtein and others. The notion of a new source of livelihood from the railway workers spread quickly among the Jewish settlers that were scattered in the nearby villages: Volka, Ditalivtsi, Brodnica, Lunin, Bostyn etc., but especially and mainly from Kozanhorodok. They all started streaming to Luninyets to find new sources of livelihood.

Walking, since they had no transportation, they went to the town in order to sell boots and other necessities to the train workers. The town discarded its old appearance and adopted a new look: new streets, entire new neighborhoods with beautiful houses. With its appearance change came a change of its name based on its rail connections; no longer the village Luninyets, but as a crossroad town, such as Luninyets–Vilna, Luninyets–Warsaw, Luninyets–Homyel and Luninyets–Rivne. All the settlements were linked and felt connected to the magnificent Town House built in Luninyets, with large, splendid buildings that surrounding it – all rendering a handsome appearance to the “new” town. The general settlement grew and expanded, and at its heels the Jewish settlement materialized, composed substantially of working artisans: shoemakers, builders, shopkeepers, bakers and so on.

In the first years they formed minyanim (Jewish groups of 10 people) and prayed in Polchovski's house, but as the space became too confining they started to build a synagogue. That synagogue opened in 1895. The first builders and officers were Tzadok Lichtstein, Yisroel Treybuch, Moshe Wolf Ditalovitski, Aharon Feldman, Moshe Aharon Hofstein, Abba Zuckerman and Dovid Greenstein. After a year or two, a rabbi was invited to the small congregation, Rabbi Alter Yehudah Zoliar of blessed memory. He served as a judge in Lyakhovichy (Bialystok) and sat on the Board of Rabbis of that town until its destruction. The big synagogue was called “Die Alte Shul”

[Page 6]

(“The Old Synagogue”), to differentiate it from the new synagogues in town built in1905, the Horodoker and Ashkenazi Synagogues.

The first synagogue was large and well-appointed, and since the first builders were Stolin Chassidism it remained the center of the Stolin sect. Praying here (in leadership) was Rabbi Moshe Trygon. The “important” and rich townspeople: Dovid Greenstein (the richest), the Hofsteins, and from the veteran Chassidim: R' Moshe Wolf Ditalovitski, Alter Levin, the brothers Ephraim-Yitzchak and Moshe-Yosef Robinroit, Moshe Boruch Cohen and Ever Lutzki. With the erection of the Synagogue and installing a Rabbi, the Jewish settlement grew from day to day. The rumor that Luninyets would soon be a major metropolis gave it wings. Jews streamed to it, not just from Kozanhorodok, but also from far away places: From Dovidhorodok, Rivne, Staszow and others. The demand for various workers grew, for shopkeepers and merchants to provide for the needs for the settlement at large. Shops opened for haberdashery and household items and so on. The various workshops and stores centered themselves around the Commissioner's house in the area called “The Market.” The distance from the Commissioner's house was no more than a 4 - 5 minute walk, and all passers by would visit the market to buy their needs.

Until 1900, there were certain streets under the town's control; Jews were forbidden to live there. There were instances when a Jew who had come from Kozanhorodok with a wagon laden with goods was denied entry and was forced to return. The Jews would not be deterred, they settled in areas of the town with or without permission, trusting their “sin” will be vindicated. Only in 1900 did the town officially accept a status as a “permitted” Jew station.

The composition of the population: Reliable sources estimate the general population until the outbreak of WWII at 10,000 people, a third of which were Jews. Most of the gentiles worked for the train line or were bureaucrats with the government, a portion of them were Luninyets farmers working the land and living in the Staro-Salska streets, or, as the Jews called them: “Die Goyishe Gassen” (The Gentile Streets”), Tsarkovna and Waradilavka Streets.

Most train workers were Poles; thus the town was comprised of Russians, Belarusians, Poles and Jews. Most of the Jews were workers and laborers: There were about 40 shoemakers, 18 tailors, 3 blacksmiths, 5 barbers (from the Musikant family), 15-20 carpenters, 10 carriage drivers, butchers, dressmakers, hatters, watchmakers and photographers. Some worked in the train workshops. The large carpenter workshop was that of Moshe Yitzchak Folksman. There were also owners of grocery shops, household goods and lumber. Of the Gentiles, almost none were craft workers - they all depended on the Jewish worker. The livelihood of the carriage drivers was in main reliant on the large wholesale distributors Dovid Greenstein and the flour warehouse of Yechiel Bodenkin. Flour sacks and other merchandise came off the ramp at the railway storage houses and brought to the warehouses of the traders, from there they were delivered to the retail shopkeepers. Distributions were difficult in the fall, on streets full of mud; paving of the roads only began with the Polish occupation. The Jewish areas were not concentrated in one place but were scattered all over. There were houses where a Jew and gentile lived under the same roof.

The Jews were concentrated mainly in a neighborhood “Oyf di zamd” (“On the sand”) in the quarter surrounding the market, and in Leib Wolf Patznik's large yard on High Street. Relationships between the Jews and Christians were not bad. There were families who were very friendly with Christians. The farmer and train worker relied on the Jewish shoemaker and clothier and his shop. The shopkeepers, tailors and shoemakers gave the Christian customer

[Page 7]

|

|

everything he needed on credit, and had to collect payments over time. On the designated collection day crafts people and shopkeepers would go to their customer's house to collect the agreed partial payment on the debt. Even after 1905 when antisemitic pogroms started, none of these were evident in the Jewish areas. The houses of the Christian population were built by Jewish builders and contractors. The main contractor was Leib Wolf Patchnik who eventually emigrated to the United States. Another contractor was Yaakov Kashten and Sons. The reigning language spoken was Russian, even the Poles spoke Russian, but the farmers spoke Belarusian. A dispute between a Jew and a Christian that reached the courts was almost always decided in favor of the Jew as long as the complaint was valid. Almost always, a farmer or peasant would actually “invite” the Jew for arbitration in front of the Rabbi. They did not suffer under the local police either; always useful and helpful was giving a “gift,” for who among the Czarist Russian bureaucrats had “clean hands” and never took a bribe?

I still remember the terrible issue my father had dealing with the matter of my dead brother who was called up, 13 years after his death, to present himself in Pinsk, to be inducted into the army. His birth certificate listed his name as “Mot'l,” but in the Oprava (official) Family Register of Kozanhorodok his name was listed as “Mordechai.” To no avail were all the assurances of the Rabbis and others that the names were the same, that “Mot'l” was simply a Yiddish endearment form of “Mordechai,” until my father “honored” the Pinsk official with 10 Rubles, who promptly declared the names are the same. That also voided the fine of 300 Rubles, punishment for those who failed to register for the army.

In the Fire Brigade, Jews and Christians worked side by side. There was an nationalist, antisemitic group, the “Black One Hundred,” some of whom lived in Luninyets; they had no choice but to deal and trade with the Jews, and in the open didn't dare to incite against them.

The schools only served the children of the train workers and the farmers. A Middle School opened in 1917 that accepted Jewish children. There was no public library until 1917 when one was established. There was a single cultural gathering place, the Kazyonni Garden, where concerts were held in the summer.

[Page 8]

During the First World War (1914–1917)

As we know, WWI broke out in 1914. The general recruitment into the army started exactly on Tisha B'Av (Jewish day of fasting). A great terror befell all the Jewish settlements in Russia, and especially in the small villages. The sudden announced conscription was of men up to the age of 44. Hearing the cries and wails of the families of the recruited males was horrifying. I returned home a few days after the announced call-up, and as I alighted from the train and entered the lit up station I encountered fellow residents, mournful and bare-headed. My mother met me with tears in her eyes because two of my brothers, heads of families, had been recruited; the oldest one, Yeshayahu, had already been sent to the front.

As the day progressed, a train filled with wounded soldiers arrived – some wounded in the head, others in the arm or foot, and this train, the first to pass through Luninyets, greatly heightened everyone's grief and anxiety. The wounded soldiers were given apples, sweets and cigarettes by a branch of the Red Cross that had been established in town. The Jews had been the first to contribute to the aid of the wounded soldiers. However, after a few weeks, the train became a regular occurrence and the rush to the station to see the wounded and distribute gifts decreased substantially. As Luninyets was a cross-lines station, trains passed through day and night, transporting thousands of soldiers to the front and bringing the wounded back from the front.

Since the war broke out the town began to experience a lack of gold and silver coins, as well as coins of smaller value. As usual, the Jews were blamed for this – that they were “hiding” the coins, but as far as attacks on the Jews, the accusations didn't reach that level. In the first days of the war's outbreak, the antisemitic newspapers in Kiev and Petersburg called for all of Russia to unite in a “holy” war against the enemy. Even the known antisemitic paper in Kiev, run by a student, Golobev (the leader of the Double-Headed-Eagle antisemitic group), turned to the Jews and proclaimed them our “Jewish Brothers” and encouraged them to enlist in the effort. The large numbers of Russians and Belarusians showed no hostility or hatred toward the Jews. The wives of the Jewish recruits received government aid distributed by the priest, as did all the Christian families. The first time I went with my sister-in-law to receive the aid, she saw all the Christian women kissing the hand of the priest and wanted to do the same, but the priest refused, saying “not necessary”, and even consoled her saying her husband will return from the war in good health.

The First of the Luninyets Jews to Fall in the War

A deep mournful fear descended on the town upon receiving news at the end of the month of Elul, three days before Rosh Hashanah, that my older brother Yeshayahu was wounded, and was in an army hospital in the village of Lyndworowa, near Vilna. He was in a batallion that stormed eastern Prussia near Konigsburg and there the Russians received their first defeat. Two divisions were totally beaten and devastated. Early Friday morning my father was on the train to Vilna. A notice came by the afternoon with the bad news – he had died. I did not know this yet, but I felt there was some sad information. As I walked in the street people stopped their conversations as I approached, and women whose husbands had been sent to the front seemed embarrassed as they looked at me. A few hours later my Grandfather, R' Shlomo Eliezer returned from Shul, entered the house, broke out crying and hit his head against the wall: “Volt Ich besser shtarben eider main Shayaleh” (Yiddish: “If only it was me who died instead of my Shayaleh”). On Sunday, the eve of Rosh Hashanah, my father returned, with the bitter message on his lips. I haven't the strength to describe the “Tisha B'Av” (somber day of fasting) atmosphere that spread over our house; Yeshayahu's widow fell on my father's shoulder, wailed with tears and cried: “From now on you'll have to be the breadwinner for me and my children.”

[Page 9]

Elders who came to our house to console my father, watched as he directed his cries upwards, to heaven: “For what reason, why?” They silenced him: “R' Sha'ul, it's forbidden! This was a decree from above – God forbid, it'll be your sin to question it!” Father quietened, and because of the strength of his religious belief and devotion became calm.

Of the Jewish inhabitants of the town, about three dozen were recruited and sent to the front. Soon after our tragedy, the main Russian headquarters started spreading provocations, such as “The Jews are spies for the Germans” and similar allegations. This caused many Jews to hide from gentiles, or desert the army or cause their own discharge by self-inflicting wounds and injuring themselves. Some actually broke a limb or even created an intestinal rupture to get dismissed under Section 66. And then there were those who, with a bribe, were “officially” registered as physically impaired and unfit.

There was no shortage of food; Jews in the city adapted and lived their lives, albeit sparingly and under pressure, but with hope that the war would not be prolonged. At the war's outbreak, all Yiddish newspapers closed. Jewish matters and concerns appeared in Russian, in weekly periodicals like Roszbet, Ivraiskya Nadilya, Russki Y'ivry and others. As the Germans advanced, many flocked to Russia as refugees. In Petroburg (its name later changed to Petrograd), at the end of 1915 after the conquest of Poland and the eastern provinces, an organization called Lyakofah(?) was established to assist Jewish refugees. As the Germans neared Pinsk the Jewish inhabitants did not know what to do. Most were sure that if Pinsk were to fall to the Germans, Luninyets would be next, so they hurried to send their families to Pinsk, thinking that in a big city the danger would be less. The deserters as well as the younger inhabitants traveled to Pinsk to escape the Russians. And thus a separation of families occurred, some were in Pinsk when it was conquered, exactly on the eve of Yom Kippur, and the others stayed in Luninyets, which was not conquered. The Germans halted at the Yoszelde(?) River, near Szczawa(?), and we remained Russian subjects. As the front came closer, a small number of Jews from Kozanhorodok, the rich and the influential, some of whom went to Komancza (Poland) and some to other cities in Russia. The Czarist Government had to overlook the Village Boundaries Law and permit this; some Jewish refugees even found shelter in Moscow.

Luninyets filled up with refugees, principally from the towns and villages near Pinsk. For several weeks, dozens of Luninyets families came to Kozanhorodok seeking shelter and refuge, but as soon as the war front seemed to stop advancing, returned. Until 1918 there was no communication between Pinsk and Luninyets. These days were called “Hayamim Hanoraim” (a “High Holiday expression: “The days of awe”) as they waited each day for the German's arrival. But the days passed peacefully; with no pogroms against the Jews except for isolated robberies by Russian soldiers who had remained behind.

After a few months the town reverted to its normal state. The shops opened again and goods and merchandise that had been hidden were put on display. Sales began, or more correctly, negotiations started. The town became a central trade site. People who in their lives had never been involved in buying and selling tried their luck in trading; some were successful. The town was filled with military enterprises. All the businesses that supplied the war-front were centered here. Organizations that supported the refugees were also very active. Working in these organizations were many progressives and socialists. In almost every house, soldiers and civilian officials dressed as army officers and considered conscripts, were housed. Due to its closeness to the front, the Russian Military governed the City.

A military intelligence unit arrived in the city, and at its head Captain Plocida (who was an Austrian and a spy as it became known after the Revolution). This captain understood and could speak Yiddish because of its similarity to German; the young men and the army deserters were deathly afraid of him. The police didn't bother them much because the police commander himself was not averse to underhanded profit. Every deserter and draft evader that fell into the police's hands was freed – with a bribe.

[Page 10]

Except for one head policeman, Karlitzki, who had “clean hands” and thus greatly feared. There was a connection between the houses that harbored deserters and evaders, so that when a policeman approached everyone was immediately notified. When children in the street saw a policeman they knew to run and inform everyone in their house.

Cultural life in the city was sparse and lacked content because all gatherings, parties or presentations were prohibited. In Luninyets, there were Russian newspapers, Kubaskaia Mysal, Poslyadnaia Novosty, and Ruskaya Slova from Moscow. At the end of 1916 there appeared in Moscow a Hebrew weekly called Ha'am (The Folk) and in Luninyets there were a few subscribers. There were no cultural events for adults. Children learned in Cheders and in private schools with the teachers D'vorah Kutnik and the Leichovitzki brothers. Amongst the deserters were a few that read and studied as well, and it changed them substantially. The basic situation in town was good. All crafts people worked; shopkeepers traded with the military businesses. With the outbreak of the revolution in February, 1917, there began a new period of social and cultural work in the city.

1917 – 1920

One ordinary morning a rumor circulated that the Czar had died. Out of great fear, Jews did not even want to hear the details from the gentiles. In a room in our house lived two officials; in the evening, the two tenants Tygnov and Dokotzayev (who afterwards became the Bolshevik leaders in Luninyets) entered and called out happily: “Landlord! We're free of the blood-handed Nikolai!” and started singing the Marseillaise. My father, very frightened, tried to stop them, saying they should take pity on him and stop singing, but they didn't listen to him and said “Don't worry, 1905 will not be repeated!” Father went out to the street to hear the news and was informed by a message from the Rabbi that Nadzyrtl, the police commander, would be coming to the Synagogue to present the new Manifest. He came and nervously read the manifest out loud regarding Nikolai, that his rule would now be in the hands of his brother, Michael. The community blessed the outgoing Czar and the incoming Michael. Two days later, the newspapers from Kiev informed us of the change, of the establishment of the new ruling government and full details of the upset in Petrograd. The Jews “had light and joy” (quote from Megillat Esther). It is difficult to even describe the joy and happiness all over Russia, and especially among the Jews. Stormy demonstrations by the army and workers took place in the streets all over Russia. Army divisions took over keeping order. The police were abolished and organized into militias

I was witness to enormous demonstrations of the political parties in Homyel (Belarus): a sea of red flags, except for two that were of a different color – those of the Zionists and the Ukrainians. All the Jewish parties, like “Bund,” and “Workers of Zion” came out with various banners in Yiddish and Russian. The prison gates were opened wide and the prisoners, mostly criminals, were freed. The deserters who had been hiding came out to the streets to enjoy the freedom. Luninyets also changed and put on a bright new face with its daily gatherings of the parties. I received the “Ha'am” weekly from Moscow in which were instructions on how to renew the Zionist organizations. The “Bund” promptly reorganized under Izel Sherashevsky (Izel the lathe machinist), Boruch Ginzberg (the demon) and the pharmacist Karman, who worked in the Pharmacy of Shlomo Hofshtein. In those days the Bund was a powerful organization. We, the Zionists didn't have much power or influence. We were just three or four of us who didn't know where to begin and had no organizational experience. Our salvation came from the Jewish soldiers that were stationed in Luninyets. Because the revolution started before Passover,

[Page 11]

Jews in Russia celebrated the Holiday of Freedom (Pessach, Passover) literally, in the full sense of the concept. On the second day of Pessach a general gathering of all the Jews in Luninyets met in the Kinomatograph (Cinema) in order to organize and choose a Jewish public committee – (Yivreyski Abshatztovni Komitet). The main organizers were Dr. Chernovsky, an army physician, W. Z. Matosov and others. They called upon the Jewish townspeople to organize, for a new period in the life of Russian Jews had begun. And the Russians, particularly those from the army, came to bless (encourage) the Jews who went from “slavery to redemption” (quote from the Pessach Haggadah), declaring with glowing speeches that from now on only fraternity, brotherhood and freedom will exist in Russia.

None of the speeches were given by Luninyetsers. But between the speeches the pharmacist (the one who worked at Hofshteins) climbed on the stage and held forth with a speech, as an assimilated Bundist, in Russian. Among his remarks, he said “Leave your Beit Midrashim and all that nonsense!” The Jewish public was furious, but didn't want to embarrass him or disturb the event because of the Christians present. But he immediately got a sharp retort from a Jewish soldier, an excellent and educated speaker. The solder was Krabtzok, who lived in our house. In his passionate Zionistic speech, he called on the Jewish community to organize and take part in the Russian revolution but at the same time to not forget ourselves, our past, or our historical homeland. The Jewish people never assimilated in the past, neither will they assimilate in the future, and to not be ashamed of our Beit Midrashim. The enthusiasm of the assembled crowd burst forth in thunderous applause. Those standing on the stage carried him on their shoulders, and we, the insulted Zionists, started to breathe again.

In that first assembly a general committee was elected. The influential strength of the Bund was displayed, as Izel Sherashevsky was elected. He was a good Jew. The assembly sent a blessing by telegram to the current new administration. After this assembly we called for a strictly Zionistic assembly, made a list of registrants and started to organize groups. Notified by a telegram from Moscow about Jews who had been expelled in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, we collected 600 Rubles for their aid. The crowd donated generously with an additional donation of 250 Shekels as we prepared for an all Russian Zionist conference in Petrograd.

In those days there was only a single Zionist organization, Tze'irey Tzi'yon (“Youths of Zion”). Tze'irey Tzi'yon and “Ha'Chaver” were popular factions, however they were outside the framework of the Zionist organization in Russia. Among the staff of the Zionists was Rishka, the daughter of Rabbi Zalman Boswitz, the ideologue of Tze'irey Tzi'yon who succeeded in negotiating with the Bundits Avrohom Yitzchak Schneiderman, the Lechovitsky brothers, Avrohom Perpelotchik, Noach Katz and, me, the author of these lines. Dr. Chernovsky, a Jew from Kursk, who spoke Yiddish with difficulty, devoted himself with heart and soul to Jewish matters, and in particular to cultural affairs. A humble man, who, out of concerns to “keep the peace,” declared himself as not belonging to any party. “I am a Jew, that's enough,” he said. He began to organize and establish a non-aligned, public library. (He secured a room in the Beis Yakov, and on his own collected books and money for this endeavor). He did this on behalf of the Chevrat Mefitzei Haskalah (Education Distributors Organization) whose mission precluded any attachment to a party. In Petrograd he secured a large collection – in one “swoop” we were enriched with hundreds of books. That is how the first Jewish Public Library in Luninyets was founded.

A short time later, we received a second delivery of books, most of them with secular Jewish themes – all publications of the Chevrat Mefitzei Haskalah (Education Distributors Company). Books such as the Jewish History Organization of Dubnow, files from Prazmow, Yivreiska Starzyna and so on. Also included were known books published by Brukhoiz, and from Odessa we received publications in Hebrew and Yiddish. In the library were some very valuable books, and the public started to read and explore not just literature but also about matters of Socialism, Communism, etc.

Participating in management of the library were

[Page 12]

Esther Hofshtein on behalf of the Leftists, and Avrohom Rodman, Tuvia Boswitz and Chaim Shteinman on behalf of the Zionists. Not satisfied with just the library, they started to organize a school. Dr. Chernovsky gathered children in the women's section of the Ashkenazi Synagogue, and in the first days he himself served as the “Melamed” (Cheder teacher). The unusual sight was: a doctor, a “physician” with army epaulets was acting in the position of a “Melamed.” He functioned like this for a few weeks until a teacher was hired.

May 1st arrived and in the now free Russia this day was proclaimed a holiday. We, the Zionists decided to participate in the celebrations with the Zionist flag. Rishka, the Rabbi's daughter, sewed a large blue and white banner, and her father couldn't resist placing on it, in large printed letters, “May Israel's Salvation come from Zion.” All the Zionists were ordered to fall in and walk behind the banner. We thought the leaders wouldn't allow us to march in the parade, but our fear was unfounded. At the head of the Worker's Council Committee were the Bolsheviks. The beginning of the procession was concentrated in the field in front of the church. In the sea of red flags were also national flags of Poland, Ukraine and the Zionist blue-and-white Banner. (Ed. note: Israel's flag did not yet exist). After reading the list of heroes of the Revolution and of those that fell, the crowd kneeled, the flags were lowered and they sang the Russian anthem.

The parade started. The National flags were in front, among them was our National flag. A stage had been erected in the large circle near the Town Building and from here speeches were given throughout the day. In the dozens of speeches there wasn't even one mention of the Jews. Izel Sherashevsky spoke in the name of the Bund and could not resist stinging the Zionists. At the conclusion of the demonstration we went to the Shul (Synagogue) of the Horodok Chassidim. Their Gabai, R' Yitzchok Katz, was a Zionist. What's more, our wonderment grew as the crowd, among them Christian officers, walked with us and entered the Shul. The Christians were interested and wanted to know the nature of our national aspirations. Dr. Chernovsky, the “non-affiliated” appeared; he wanted to pray the Ma'ariv and stood at the lectern and led the prayer.

|

|

[Page 13]

The faces of the devout glowed with pleasure. After the prayer, Dr. Chernovsky stepped up on the stage and gave a speech, in Russian, on Judaism and the Jewish people, entitled “The Eternal Wanderer.”

Honoring the speech, the youths applauded, clapping hands; the devout with loud blessings. After Dr. Chernovsky's address, a Russian colonel asked permission to speak – and heaped praises on our ancient people. He promised that, from now on, they would all be free citizens.

The cultural life of the Jews advanced with giant steps. In Petrograd a Yiddish newspaper appeared, the “Petrograder Togblat” (Petrograder Daily), edited by Yitzchok Greenbaum. In Moscow, “Ha'am” (The Folk) became a daily paper, and another daily in Kiev, the Zionist “Der Telegraf” (The Telegraph), edited by Dr. Syrkin, the leader of the Ukrainian Zionists. In addition, a Bund daily paper appeared in Minsk, “Der Vekker” (The Waker), edited by the well-known and famous Esther (Frumkin) Company. Kiev also produced another daily, “Die Nyer Zeit” (The New Time), edited by Dr. Zilberfarb. “Ha'Shaluach” (The Sender) was renewed, and in Moscow a weekly publication for youths, “Shtillim” (Seedlings), edited by Ben-Eliezer. New books were also published in Odessa. Hebrew and Yiddish literature began to prosper, but to our great chagrin the honeyed months after the Russian revolution did not last long. It was only a short time till the Bolsheviks took over. This changed the political and party life in Lunenyets. Week after week our town was visited by speech-givers from the Bund party, the Zionists and from other parties, but mainly from the Bund. The Bund was centered in Minsk; permanently seated there was Esther Frumkin, editor of “Der Vekker” and her husband, Yerachmiel Weinshtein. Esther visited Luninyets as well. Jewish students from Minsk came and argued with each other. Addressing the Zionists were excellent speakers: the student Natan Pintzik, the student Hochshtein and others.

The Beginning of the Russian Rule

In Luninyets the rule passed to the local Russian government. At its head stood Tegnov, a typical idealistic Russian teacher dedicated to Bolshevism. The Jews had not even one representative because the Bund resisted the Bolshevik dogma. The upcoming elections at the founding general assembly and the general Jewish assembly in Russia launched a fierce voting fight in the town. The Bolsheviks did not interfere with the parties and their propaganda. All of the great powers of the Jewish parties sent speakers, including some to Luninyets.

I should note that at that time, most of the Jewish workers in Luninyets belonged to the Bund – not because of any Socialist leanings, since most were religious and kept to their traditions; belonging to that party was more psychological, and responsible for this were the civil citizens that distanced themselves from the worker and the craft person, calling them “Um Ha'aretz” (ordinary and uneducated people) and were embarrassed by them. We were encouraged to proceed with the elections when Moshe Kutnik from Mikaterinoslav came to us; an accomplished teacher, an entrepreneur and organizer and Dr. Fakar, an army doctor, both leaders of the Zionist Youth in Poland. They organized the soldiers from all districts of Luninyets, and called them The Military Zionist Council. The Council established itself in the house of Yitzchok Katz.

The general elections list of Zionists was called “The Jewish World Election Committee.” The Jewish Socialist parties had a separate list for the Bund, together with the Mensheviks. At the top of that list stood Rabbi Yaakov Mazeh who was

[Page 14]

famous for his role as a witness in the infamous Beilis trial (Blood Libel). In all the links for which a candidate from The Jewish World Election Committee was named, those chosen were Zionists or close to Zionism, among them: Rabbi Mazeh, Dr. Brotzkus, the engineer Syrkin from Kiev, the known judge Grozenburg and seven other influential Jews. Of the Jewish Socialist parties, not one person was elected. Even in the elections of the general Jewish Russians, in which the Zionists had a separate list, we won. But here's the crux of the changes with the elections in the most important parties: Despite all our efforts invested in the elections, they came to naught; when the Bolsheviks joined the assembly and realized they had no majority they forcibly dispersed the people and arrested many of the dissenters. From then on they ruled “with a high hand.” As a result of the prolonged war and the great neglect in the communities, the big cities were experiencing a lack of bread, salt and other necessities. The farmers stopped bringing their produce to market. Provocations against the Jews started here and there because the head of the Bolshevik government was (Leon) Trotsky, a Jew, therefore all Bolshevism was Jewish… Even the major liberal Moskow newspaper “Russkoye Slovo” published articles against the Bolshevik rule, inflaming the public against Jews by naming its leaders and adding “The Jew” in front of each name: Trotsky, Bronshtein, Zinoviv, Appelboim, Kiminev, Rosenfeld, Satklov, Nechamkes, Redak, Sobelsohn and so on. The “Black One Hundred” (the ultra-nationalist, antisemitic group) carefully took note and raised its head.

Also at that time we received a telegram from Minsk about the 1917 Balfour Declaration. We called for a celebration by the Zionist “club” that was in the house of Yitzchok Katz. We cheered up and waited with bated breath for further news and developments. We also saw a return of the founders of “Ha'Chalutz” (The Pioneer), led by its captain, Joseph Trumpeldor.

The Bolsheviks, in their desire to please their constituents and at least keep one of their promises to the electors, entered into a peace treaty, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Germans. This raised the ire of all the socialist parties, and in particular, the SR party (Socialist Revolutionary Party), who started to terrorize the public. In Moscow the German Ambassador to Russia, Graf Mirbach, was murdered, and in Petrograd, Vladimir Lenin was wounded.

The German Entry

One bright morning, as residents of Luninyets stepped out into the street, they noticed German soldiers. The soldiers claimed the mission between Germany and the Ukrainian government was to “free” Ukraine and Belarus from Bolshevik rule. In Luninyets a group of Ukrainians organized; that is to say: all those who once worked in the Nikolai (Ukrainian) government. In the Ukrainian days, despite everything, we kept up with our work; we led evening classes in Hebrew, and arranged for lectures every Shabbat. Those who during the war years had been in Poland under the German occupation started to return to Luninyets. Especially those who had been in Pinsk. Business people from Pinsk visited us, and last but not least came Chaim Glaubersohn, the teacher; all those returnees from the German occupation were dejected, hungry, and in rags. The relative silence did not last long. The Germans eliminated the Ukrainian administration and installed the Hetman (official title of a military commander) Skoropadsky. Jewish Ukrainians gathered enough church goers under the leadership of Usishkin to choose a few individuals to join a Conference of Peace. After the defense against the Germans at the eastern front, a revolution broke out in Germany as well, and the German army started to return to Germany. They sold everything they had in their storage warehouses – arms, equipment and everything else. The Bolsheviks bought much of the arms and after the Germans' exit, took over the rule again.

[Page 15]

The new rule organized in Luninyets had as its Conductor (sic) Garaglyad, who lived on Brodilovka Street.

The private Hebrew teachers joined together and formed a school which was included in the network of the Government Schools. We continued to teach in Hebrew as before, but with the new circumstances turned to teaching in Yiddish. All was fine until the Jewish Bolsheviks got wind of it, although they still did not cancel our efforts because in the meantime, war had broken out between the Bolsheviks and the Poles.

The Polish Entry

Changes in the administration of Luninyets were not rare. After the Bolsheviks, the Ukrainians ruled; after them, the Germans; then the Bolsheviks ruled again. And now, the Poles. They were drunk with the notion of their nationalism and the revival of their state and independence. And while only a few months had passed since their “rising from the dead,” they certainly were not novices in their hatred of Jews. In the first conquest they were content with just looting and robbing old men. But now, after only a few days, they proclaimed: All signs in the city must be in Polish. The Poles in Luninyets woke up, and of course appreciated the new Polish rule in the city and its institutions. In offices they spoke and answered strictly in Polish, disregarding the fact that most could just dabble or barely speak in broken Polish. Many children of Luninyets, Poles from birth, were unfamiliar with the Polish language (Ed. note: Their “mother tongue” was Russian).

We had no choice but to start learning Polish. Our study of Torah was reduced by the fact that we had to be able to accurately hand-write, in perfect Polish, a formal request in order to receive a “Passage Permit,” without which, leaving the city was not possible. The Poles advanced their conquests with giant steps and, after a while, reached as far as Kiev. The Bolsheviks had their hands full, dealing with wars in front and back: With General Yudenich in the north, with Symon Petlyura in Ukraine, with Admiral Kolczyk and after that with General Denikin in the south, but in the end they succeeded in defeating all their opponents. The Poles started to retreat, but their retreat was actually their escape. At the head of the Red Army, or the Red Guard as it was called then, stood Trotsky, who with his organizational skills and talented speech and propaganda, subdued all the forces that opposed the Soviet rule.

The Red Guard soldiers, tired, tattered and barefoot, with meager equipment, carrying obsolete weapons, nevertheless succeeded in pushing off the Poles. Luninyets was greatly affected by the retreat of the Poles. Besides the looting and disturbances they caused outside of the central city districts, particularly, of course, in the Jewish houses, the beautiful new library founded by Dr. Chernovsky was attacked and went up in flames. The Poles shot and killed Yitzchok, the Rabbi's son, and Benny Tamarin. They kidnapped men for work without informing them as to where they were taken. For three or four days the city was abandoned, a no-man's land for the Polish soldiers, and only when the Bolsheviks came did we breath a sigh of relief. Unfortunately, after a short time, just about two months, the Bolsheviks that had already conquered the suburb of Praga and were about to enter Warsaw started to retreat in flight. Fear and trembling gripped the Jewish settlement. Many left the city, especially those that were suspected of being “leftists.” The fear grew as we learned of the slaughter the Poles had perpetrated in Pinsk; 37 of the best businessmen in Pinsk had been shot by the Poles for no reason. Together with the Poles were the rioters known by the name “Bolakhovich,” who murdered, robbed, raped and laid the Jewish villages to waste. But a miracle happened in Luninyets when the Poles entered and preceded the Bolakhovich hordes. And thus we “celebrated” that

[Page 16]

only through looting and rioting were we saved by the second Polish conquest of our town. According to the peace treaty between the Bolsheviks and the Poles, the border was established in Mistowice, Poland, and from then on Luninyets was annexed and became part of the Republic of Poland.

Under Polish Rule

The changes of governments, the Bolshevik confiscations, the Polish robberies and the burning of Jew's houses depleted and thinned out the Jewish settlement in Luninyets. The workmen were out of raw materials; the shops remained empty. Many families, especially widows and families whose breadwinners had left town were mired in depression. But all were satisfied that at least they'd been saved from the Bolakhovich gangs. The town was wounded and broken, but slowly, very slowly, the wounds began to heal. After a while the connection between businesses in Luninyets and Warsaw was renewed. The “Joint” (Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) sped up its help to our town. Thanks to the help of American Jews many families were saved from the hunger and cold, and many organizations came to life.

In Luninyets, school opened with all its classes and all the town's children were enrolled. The school had 7 teachers, with Moshe Kutnik at their head. Free textbooks were distributed to all the children. A Kitchen was established to serve orphans and children of the poor; there they received milk-cartons as well as hot foods. From the Joint we also received parcels of clothes and shoes that were distributed to the needy. A clinic was opened and Dr. Gurwitz would come to receive patients and distribute medicines. The clinic and the school were located in the large house of Moshe Ditalovitsky, the house that had formerly housed the occupying Soviets.

All this social work was managed by a committee headed by Izel Sherashevsky, Dovid Brodnitzky, Moshe Kutnik, Likhovitsky and others. Aid from the Joint had also been offered during the first Polish conquest – it was renewed after the second conquest. The “Keren-Or” (Ray of Light) organization sent delegates from America under the auspices of the “Relief Committee of the Sons of Kozanhorodok and Luninyets” in America. Hershel Dannenberg, one of the delegates, originally a Luninyets native, the son of Reuven Dannenberg, in addition to the greetings, brought with him actual aid. Almost every family received money that had been sent by relatives in America. He also brought many affidavits (financial guarantees) needed for those who wanted to travel to America. The Jewish settlement was revived and the economic life was back on track. Dozens of people, among them whole families, left Luninyets and traveled to America; at that time the gates of that country were still open (no quota restrictions) to refugees.

A new shift in public life began. We collected books and “refreshed” the library. A large shipment of books from Warsaw that had been ordered before the Polish conquest, arrived. We named the library after Yosef Chaim Brenner who had been murdered in Jaffa, Eretz Yisrael (Palestine), in 1921 during an Arab riot. The Zionist party was reorganized anew. We received members from Pinsk, Avraham Meyerovitz, Hershel Pinsky and others. Sent to the Tz'eirey Tziyon Committee that convened in the summer of 1920, was a delegate from Luninyets – the writer of these lines. Also, the teacher Chaim Glaubersohn was sent as a delegate to the General Zionist Committee gathering in Lodz.

In 1921, under the Culture Committee, a Beit Midrash for teachers opened in Vilna, with courses in pedagogy, and under the Ort Organization a Technion (technical) School was established. Many young students wanted to “relax” a little from public service and went to Vilna to “sit on the bench” and study.

by Asher Plotnik

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

At the beginning of the twentieth century Luninyets was still very young. The town was built on a large level field, surrounded by forests of pine trees. To the North-West there was an extended marshland, where many birch trees grew, as well as other trees and shrubs that served as burning-wood. In the winter, the peasants would chop the trees and bring them to town on sleighs, during the rest of the year no person would set foot in this marsh area. To the East and to the South, sands and also black fertile soil extended to the horizon, and when the town grew in size and in population these soils were transformed into cultivated fields, growing wheat and potatoes. The place was not blessed with a river or streams; therefore a large settlement has not developed there.

At the beginning, only very few peasant families, poor and destitute, lived there. Only when the railroad tracks were constructed in the vicinity, the town became awake and an enormous movement of construction began.

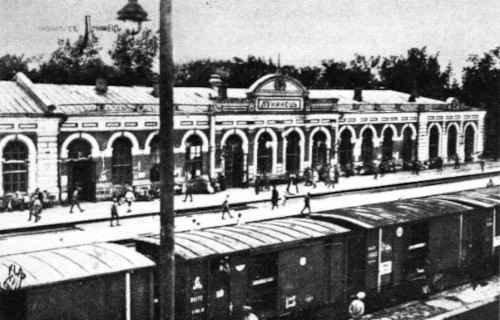

The most impressive building was the train station, which in time has become famous. It was built of brick and white stone, decorated with cornices and other ornaments, and had tall arched doors and windows. There were special rooms for the director of the station and the various managers, ticket booths and luggage rooms, large waiting halls for first and second classes and a snack bar. The third-class waiting hall was always full of peasants, workers and others, who, while waiting for the train, drank tea that was distributed freely day and night. Many drank vodka from bottles they had bought at the co-operative store next door and of course some of them were drunk, rolling on the floor, snoring or vomiting.

The first and second-class waiting hall was breathtaking. The tall windows were covered with silk curtains. Palm trees grown in pots were placed in the corners. Little tables and upholstered chairs were scattered in the large room; the snack-bar was upgraded and well stocked. The customers were respected merchants and high officials - the “simple folk” were not allowed to use the facility. In the neighborhood of the station, large apartment houses and administration buildings were erected and telegraph poles and telephone lines were installed. All this called for workers - simple laborers as well as professionals. The simple workers came in masses from the neighboring villages and the professionals from the larger towns and cities. Many Jews found employment in the region: they opened stores, bakeries, restaurants, taverns and small workshops. The forest and grain businesses began to grow, as well as other large enterprises. Many Jewish workers were employed in the train-station buildings.

All these new workers, Christians and Jews, acquired land, which usually was marshland or arid land, but they worked hard and drained the terrain, built houses, planted gardens around their houses and grew pigs, cows and chickens. Wealthy non-Jews came as well, built houses and shops, and rented them to Jews. They planted orchards around the town, with apple trees and pear trees, cherries and plums, and several berry-growing shrubs. All these trees and shrubs gave the town beauty and grandeur, especially in the spring, when the trees blossomed and the fragrance of the flowers filled the air. When the authorities began naming the streets, the main street was called “Garden Street”. At harvest time, these gardens would provide a livelihood

[Page 18]

for many Jews, who were hired to pick the fruits and made a few Rubles. The town gardens served the children as well, either for playing or for mischief. They would climb the tall fence, pick apples before they ripened, jump rope, or unfasten the nails of the fence. Later, when they had the opportunity, at twilight or other time when people would not be around, they would enlarge the opening of the fence, go in and fill their pockets with apples and pears that had fallen to the ground. The Jewish boys were especially fond of apples and pears, and the black-red cherries attracted them as with magic. No Jewish boy, even the most gentle, could pass near a cherry tree and not be tempted to pick some fruit. The chestnuts would serve as playing things.

When the Jews began to settle in the town, they built beautiful houses and nice fences around their courtyards, but few of them planted flowers or fruit trees. Indeed, the Jews have learned many things from the gentile peasants - almost every Jew had a cow and chickens, but not fruit trees and flower gardens.

At that time, typical Gentile rural and agricultural neighborhoods developed as well: low houses with thatched roofs, cattle corrals and courtyards full of manure and junk, and chickens poking around and laying eggs in all corners of the yard; dogs and pigs wandered freely in the streets. Some of the Jews, who could not afford to buy a house in the center, rented land far from the town, built houses and for several years had to cope with the water and the mud, and the distance from the center. Some of them succeeded nevertheless and planted little vegetable and flower gardens.

In twenty-five years, the once abandoned and desolate place turned into a large and flourishing settlement. The majority if its residents were Christians, but also a considerable number of Jews, all in a community that was growing and developing constantly. This mixed population caused sometimes confusion, especially among the street beggars, who could not distinguish between a Jewish and a non-Jewish house…

As the Jewish community grew and commerce developed, public and social life began to evolve in Luninyets. In particular, a special political awakening could be observed among the Jewish young people in town. Those were momentous times - the year was 1905, the time of the Russian-Japanese war and the eve of the revolt against the Czar, a time of social upheaval and collapse of the tyrannical regime throughout the country. The events reached our young little town and the flag of the revolution was raised here as well. The first steps were taken secretly and the underground meetings took place in the back rooms of the houses, in a grove or in the forest; but later they were held openly, as the revolt proceeded. Finally, when the great railroad strike began, the entire town seemed to stop living. Many of the town's residents were railroad and telegraph workers, most of them organized in political parties and active in the revolt. The strike brought fear and anxiety to the town. The whistle of the arriving trains, day and night, was not heard any more; the big station was closed, the cars and locomotives stood idle on the tracks; workers walked in the streets with nothing to do. Mounted policemen filled every street and alley, staring angrily in every direction.

The Jewish young boys and girls in town were very active in the general revolution

[Page 19]

movement. Among the Jewish revolutionary groups they were called “The Democrats” or “The Sisters and Brothers.” The underground meetings would take place in the forest outside the town, the young people carrying guns under their clothes. The head of the “Sisters and Brothers” was Leibel the son of the rabbi, who had left his home and the traditional upbringing and joined the rebels. Fear and panic was great among the Jews in town. The young men would paste on the town bulletin boards proclamations in Russian and Yiddish, received from the central leadership of the revolution, which called for the overthrow of the Czar. Intense propaganda for a new revolutionary regime in the country was conducted. In our house they recited slogans against the Czar and against the Bourgeoisie, and sang the Marseillaise, symbol of the revolution, and other revolutionary songs with either patriotic or sad, heartbreaking melodies. Our parents, out of fear for their own and for their children's fate, could do nothing but listen and worry. Sometimes they did express their anger against the “hooligans” who honestly believed that they could destroy the Czar Nikolai; contrary to the young people, the older generation was doubtful: “Yente and Sara of the 'democrats' don't like the Czar Nikolai” - they would grumble - “so they are taking action…. the days of the Mashiyah [Messiah] must already be here, since it is clearly written that when the Mashiyah will come, the 'chutzpa' [insolence] will reign supreme….” The Sisters and Brothers, however, took their activity seriously: they began acting as arbitrators in labor disputes and as judges in civil and criminal trials; they declared strikes, took construction workers off the scaffolding if they worked more than eight hours a day, and threatened the contractors with punishment if they would not obey their instructions and carry out their verdicts. Indeed, the revolutionary spirits were high and the revolutionary “democrats” ruled the Jewish street, until a terrible event occurred, which inflicted fear on the Jewish community: the head of the town's police, Kowalski, was murdered. A great number of policemen arrived to the scene of the murder, searched the streets and the houses and made arrests, among Jews and Christians alike. The panic among the Jews was great and they feared a pogrom. Even the Cossacks came, but thanks to the good relations between all parts of the population, the matter ended in arrests and trials only and finally the town calmed down. Some of the Jewish young men were sentenced to prison in Siberia, and returned home only at the time of the great revolution, in 1917, their spirits broken and their bodies hurting. Others fled the country and found refuge in the United States. The revolution was crushed with brutal force. Many accepted the situation in despair, especially the Jews, who tried to return to a quiet and peaceful life. The laborers and craftsmen continued to earn their living with difficulty, as before, however deep in their hearts the rebel spark was still alive. It was expressed in various ways, as, for example, in the charity institutions and other constructive projects that were initiated in our town.

As the revolt was crushed throughout the entire country, our town calmed down as well. The horrible nightmare was over. Commerce flourished again and work was available. The Jews - men, women and children - could again take their regular walks on Sabbath afternoon, between the afternoon and the evening prayers, through the park or the beautifully paved square near the train station, to hear and see the train arrive. It would enter the station with pomp and great noise, and the people would enjoy the sight of the spacious and well-lit train-cars, especially the restaurant car, occupied by important and honorable people, elegantly dressed. For some time, life would again run its regular course.

by Chaim Rubinraut

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

General Review

In the war between the Poles and the Bolsheviks, the town was occupied by the Poles, who held it until the beginning of the Second World War, in 1939. During the Polish rule Luninyets developed and flourished. Streets have been paved and sidewalks constructed, and trees planted along the sidewalks. Even the old synagogue-lane changed its looks. Many public institutions were built at the time: a Polish elementary school, a folk-theater, a government high-school, as well as buildings for the administration and the military and a movie theater. Eight medical doctors worked in town, four of them Jews. The three dental clinics were run by Jewish dentists. The population grew to 10 thousand - 5,000 Russians, 3,000 Jews and 2,000 Poles. A new Town Council of 16 members was elected, five of them were Jews.

The Jewish communal life changed as well: elected members of political parties and economic organizations became the leaders of the community, instead of the various lobbyists and “managers.” The Zionist parties were reorganized and workers unions were established - craftsmen, merchants, butchers etc. Two banks were opened: the co-operative bank and the bank of commerce.

The Zionist Movement

All the Jewish youngsters were part of the Zionist movement, as members of the various parties. The “Bund” and the Agudat Israel were not represented in Luninyets at all. The most important Zionist organization was “The League for the Working Eretz Israel”, which had the largest membership.

Every family took part in the activities for the benefit of the JNF [Jewish National Fund] and the youngsters were thoroughly dedicated to their work in support of Eretz Israel. The enthusiasm for Aliya was great, and despite the severe limitations imposed by the British the number of emigrants from our little town was considerable. Young pioneer men and women went to the various Zionist training camps in Poland, to get ready for Aliya. Among the first “illegal immigrants” to Eretz Israel, many were from Luninyets. Some of the great leaders of the Zionist movement visited our town: Berl Locker, Baruch Zukerman, Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Yosef Baratz, Yitzhak Schieffer and others.

The Religious Life

There was almost no religious fanaticism in town. Tolerance and understanding of the modern times were the rule. The synagogues were open for public meetings of adults and young people, men and women. The four synagogues in town were the center of the religious life, and only lately a Talmud Torah and the Yeshiva Bet Israel were built - large and beautiful buildings, which also served as meeting places for the Zionists. The Luninyets Jews supported the Yeshiva students and donated money to the other Yeshivas as well, through the “emissaries” [shaliach] who visited the town for that purpose and sometimes gave a sermon encouraging the Torah learning. The majority of the Luninyets Jews were Hasidim of the Stolin and Karlin dynasties, and smaller groups were Horodok and Brazna Hasidim. The yearly visits of the Hasidic Rebbes brought to the town a festive atmosphere, and the youngsters would take part in the celebrations as well.

R'Alter-Yehuda Zolyar of blessed memory, the first and last rabbi of Luninyets, was

[Page 21]

the head of the Jewish community during more than four decades, until his last day. He was admired and respected by the entire population.

Education and Culture

During the last 25 years, great changes in the field of education took place in our town. Less and less children were sent to learn in the Heder; the parents preferring the Jewish “Tarbut” schools. About 50 children went to the Heder and Talmud Torah and the yeshiva had 80 students, most of them from other towns. Our young adolescents chose high-school and university education - many of them went to high-school in the larger cities: Pinsk and Baranowitz. After they graduated from their high-schools they went to the universities of Warsaw, Vilna or Lemberg. The “Tel-Chai” Jewish library contained about 2,500 books in the Hebrew, Yiddish and Polish languages, and Yiddish and Polish periodicals. The library hosted lectures and discussions on literary and political subjects, and sometimes held “literary courts.” A drama group was established and they often presented plays to the community audience.

The Economic Life

The economic existence of the Jewish merchants, craftsmen and laborers was in close relationship with the train workers and the administration officials in town. The connections with the “gentile” villages in the neighborhood also had a positive effect on the Jewish commerce matters. The Jewish population provided a good market for the agricultural produce of the villagers: grains, fruits and vegetables, hay and wood. The peasant usually possessed cash and served as an important factor in the general commerce and labor relationship with the Jews. The mutual rapport between the two parts of the population was based on fairness and trust, and during the first years of the Polish rule the economic life was conducted smoothly and efficiently.

However, these days did not last long. Great economic and political changes took place in Poland, affecting Luninyets as well. First was the official economic boycott on the Jews, openly imposed by the authorities. The Polish government decided to remove from Jewish hands the small businesses and workshops, in order to help the Christian population take over these fields of trade. Polish shops and workshops and Polish co-operative department stores opened, and financial support from the government enabled them to compete easily with the Jews. Jewish shops were forced to close and Jews began a difficult struggle to earn a living. This situation intensified the desire to leave the Diaspora and its troubles, and indeed the young men and women began to flow to the “Hehalutz” training camps and prepare for Aliya.

The Beginning of the End

With the outbreak of the Second World War by the end of 1939, when there was great fear that the town would be occupied by Hitler's army, the victorious entrance of the Red army was considered a hope fulfilled. However, as the Soviet rule was set up, the national and cultural activities in town were brought to a stop. The Jewish community life and its cultural and educational organizations and activities were paralyzed. The “Tarbut” schools and the other educational institutions and libraries were closed, and

[Page 22]

the books that did not conform to the communist doctrine were destroyed. The rich and extensive Jewish press disappeared. Instead, small Jewish communist newsletters were published, containing soviet official news. The Jewish holdings in the banks were confiscated, as was the merchandise in the stores. The Jewish population, merchants and laborers, formerly busy with the struggle to maintain their businesses and develop, was now having one simple and basic worry: how to bring home a piece of bread for the children. The fear of hunger was becoming very real.

Total Destruction

The Soviet rule in Luninyets ended in June 1941. The deadly events that occurred in Eastern Europe and the wild storm that swept the area reached Luninyets as well. Hitler's cruel soldiers broke into town and began murdering systematically the Jewish population. The first massacre was in the Jewish month of Av 1941. Almost all the men over 14 years of age were murdered and the women and children were imprisoned in the ghetto.

The second massacre occurred in Elul 1942. All the inhabitants of the ghetto were killed - shot and thrown into a mass-grave. All their property and possessions were robbed and stolen by the gentile population.

That was the bitter end of the Jewish holy community of Luninyets.

The Jews in the Surroundings

Luninyets was surrounded by smaller villages. 150 Jewish families lived in these villages, most of them craftsmen. Some had small shops, some were peddlers or owned flour-mills. In matters of religion and kosher slaughtering these village Jews were connected with the Luninyets community. On festive occasions, as weddings or circumcisions, they were helped by the Luninyets rabbi or Mohel. Their dead were buried in the Luninyets Jewish cemetery.

The Jews in the villages Lunin, Tzotzwitz, Bostin and Dyatlowitz had their own Torah Scroll and held Sabbath prayers. For the High Holidays they would invite a cantor from Luninyets.

We cannot list the names of the Jews killed in the Holocaust. We mention below the names of the villages and the number of families that had lived in each of them.

| Families | |

| Tzotzwitz | 25 |

| Tzotzwitz | 25 |

| Novosyolok | 3 |

| Wolota | 5 |

| Malkowitz | 25 |

| Bostin | 20 |

| Dyatlowitz | 15 |

| Lowtza | 3 |

| Lunin | 20 |

| Wolka 1, near Lunin | 3 |

| Yezbinok | 3 |

| Rokinta | 3 |

| Yezibok | 3 |

| Witzin | 3 |

| Drebsek | 3 |

| Tzena | 3 |

| Wolka 2, near Kozhanhorodok | 10 |

| Brodnitza | 3 |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Luninyets, Belarus

Luninyets, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 03 Nov 2025 by JH